The railways were always intended to move people and produce for profit, but with those products and people moved information and ideas. The railways broadened people’s horizons, not just by permitting them to travel as never before but also by speeding up older forms of communication and facilitating entirely new ones. The nation would be linked up physically and culturally, almost by accident, in ways that changed the entire political and social landscape of Britain.

Naturally, the first thoughts about railway communications were concerned with conveying information between staff about the running of trains. The very first railway lines were equipped with little in the way of points, junctions or even many engines. What did exist was managed with a combination of flags, lamps, pocket watches, messengers and memoranda. In essence, when a man sent a train off along a section of railway line, he made a note of the time of its departure. After a full ten minutes had elapsed, he could send another train along the line, warning the driver as he did so that he should proceed with caution. However, if a longer period of time elapsed between messages being sent (different stretches of line had different time intervals), then he would tell the second driver to expect a clear run. This system worked reasonably well – so long as there were not many trains on the line in question, they travelled fairly slowly and the drivers kept a sharp eye out for trouble up ahead.

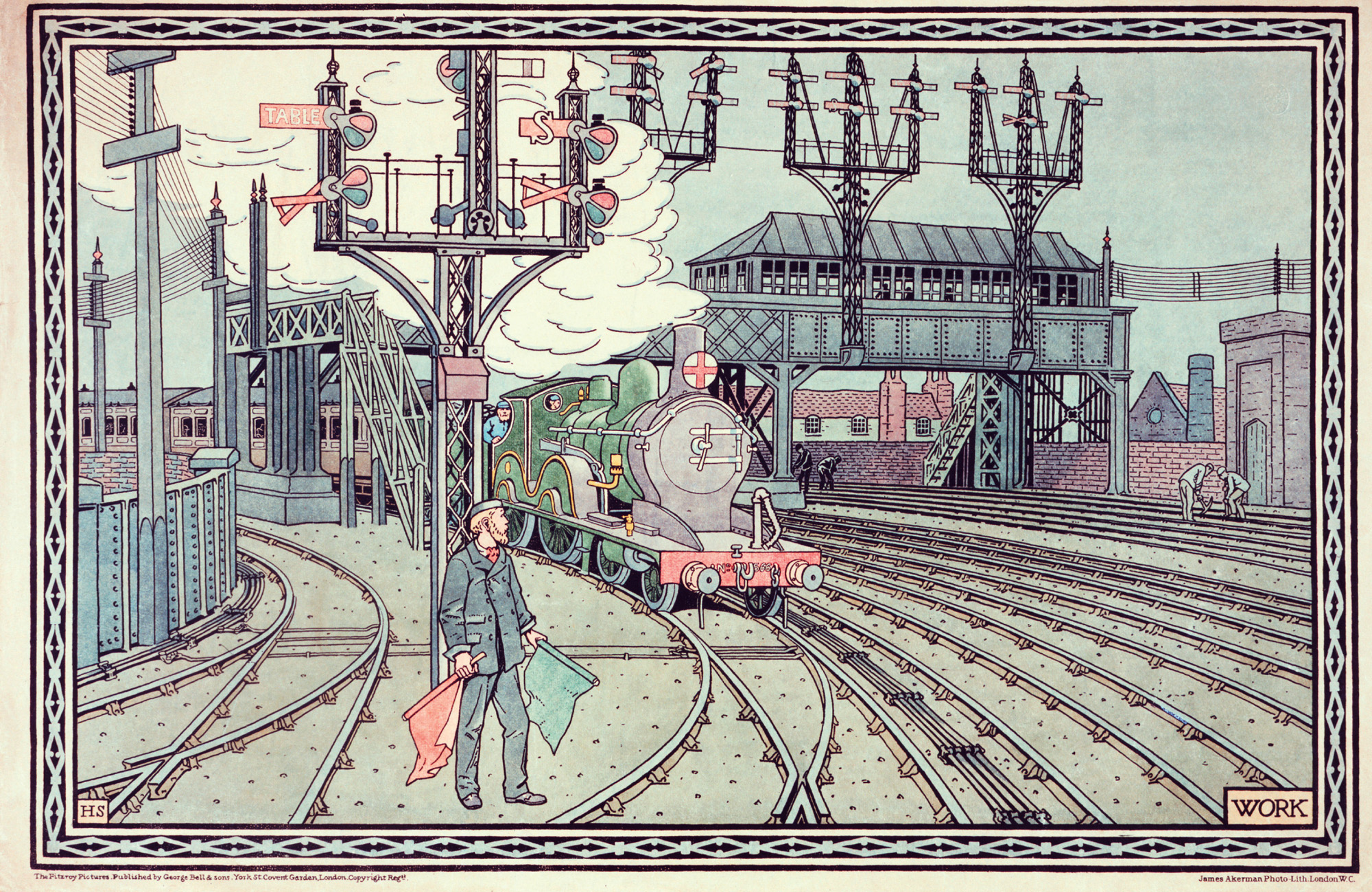

Signalmen (who to begin with were known as railway policemen) were stationed at intervals along the line with their trusty watches and notebooks. In order to slightly speed up the system, they were issued with flags and lamps. These allowed the signalmen to communicate with the driver without the train actually having to stop each time it reached a signal post. If the signalman needed to stop the train, he raised both arms above his head, waved a red flag or lamp or, in extremis, attracted the train driver’s attention ‘by the violent waving of any object’. ‘Proceed with caution’ was signalled by raising one arm above his head, or a green flag or lamp; the ‘all clear’ signal consisted of one arm being held out horizontally across the track, or a white flag or lamp. A little ditty helped everyone to remember the signals: ‘White is right; Red is wrong; Green is gently go along.’

Before long the signalmen were assisted by a stout wooden pole driven into the ground, from which hung a painted wooden board or an arm operated by a rope or wire. The signalman could haul on the wire to change the position of the signal arm, mimicking the positions of the original hand signals. The arm could be positioned vertically, horizontally or at a forty-five degree angle. Being both larger and taller than a man, such signals could be seen over much greater distances and in conditions of poorer visibility. The idea was borrowed from the military, which had used similar devices for sending semaphore messages across battlefields. The only problem occurred when the wires broke and the signal arm dropped down into the horizontal position which, mimicking the original arm movements meaning ‘line clear’, left the signalman with no way of moving the signal to the vertical ‘stop’ position. Several crashes later, the meanings attributed to the positions of the signal arms were reversed, so that the horizontal dropped position now meant ‘stop’ and the driver could only proceed when the signal had been positively raised or ‘pulled off’.

Regular timetabled services for passengers were governed not only by the pocket watches and notebooks of its signalmen, but by those of the railway’s drivers and station staff as well. This was fairly straightforward between Liverpool and Manchester, on that first regular steam-hauled passenger service, but the Great Western Railway had a more fundamental problem on its hands. In the nineteenth century, throughout Britain, towns and cities set their clocks to local mean times, based upon astrological observations. This meant that noon did not occur at the same time in Exeter as it did in Bristol, and the time in Plymouth was a full twenty minutes off that in London. Local clocks reflected these differences.

“IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, ACROSS BRITAIN, TOWNS AND CITIES SET THEIR CLOCKS TO LOCAL MEAN TIMES.”

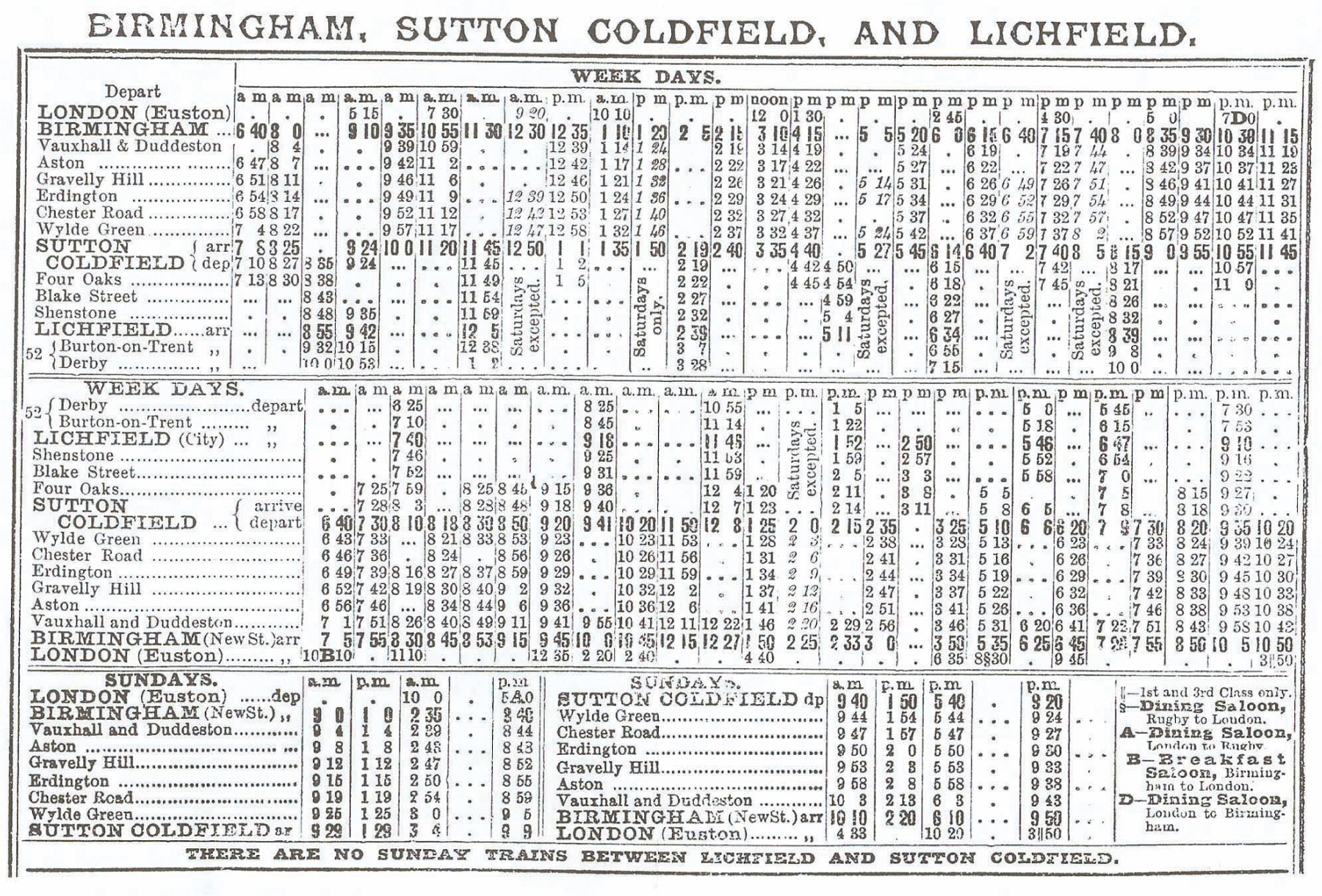

This was a problem that was already requiring the attention of drivers and signalmen directing mail coaches on their regular, timetabled runs. The railway companies addressed the matter by issuing the guards with adjustable watches that could be moved forwards or backwards the requisite number of minutes as they passed through local time zones. Early editions of Bradshaw’s Railway Guide consistently give local timings that appear to show west to east journeys taking significantly longer than east to west, as a direct result of the differences between these local time zones. Inevitably, a decision had to be taken to adopt Greenwich Mean Time all along a line, rather than reflecting the local time in the area that the line passed through. However, confusingly – and highly disruptively – this was a decision that was taken by different railway lines at different times.

Unsurprisingly, those with the most to gain from such a chronological rationalization were the east to west lines, and these were the first to make the change to standard Greenwich Mean Time. The Great Western announced its intention to run forthwith in this way in 1840. Its timetables, also, would only give the standard time. Other lines began to follow suit, but it was an extraordinarily confusing decade for railway users, with some lines using local times and others, often connecting with or running alongside, using Greenwich Mean Time. Meanwhile, the towns and cities that the trains ran through might stick with their local time, or they too could have changed over to what was increasingly called ‘railway time’. Some stations tried to ease the situation by providing clocks that showed both local and railway times, adding a second minute hand. To make a connection between two services, a passenger needed to know what time each of the two railway companies kept, the local time where he or she boarded the train, the local time of the connection, and the local time of the final destination. The clocks that they encountered during this journey might display railway time or local time or both, probably without any indication upon the clock of which was which. By 1855, fortunately such problems were rapidly easing. The various railway companies, nagged in part by the Railway Clearing House, had fallen into line and, rather more extraordinarily, so too had ninety-five per cent of Britain’s towns and cities. One after another, they abandoned their own traditional times and moved over to ‘railway time’. The law was not to change until 1880, but by the time it was finally introduced, to all intents and purposes the railways had already standardized time across the country. It was just one of the many shifts from a local to a national viewpoint that the railways were to bring.

Whilst information about the running of trains was based largely upon pocket watches, notebooks and timetables, information about the carriage of passengers was managed through tickets. ‘Joseph purchased five little slips of paper – intrinsically worth about one farthing – for the enormous sum of nine pounds and ten shillings sterling’, wrote John George Freeman in his journal in 1873.

The concept of the ticket is a rather odd one, when you stop to think about it: a small slip of paper or card that gives you the right of access to a specific service, regardless of any other consideration. It takes no account of who you are or why you wish to use the service and it has no intrinsic value of its own. The lack of a ticket leaves you out in the cold, perhaps literally. Cash itself is useless if you cannot convert it into a ticket.

“ONE AFTER ANOTHER, THEY ABANDONED THEIR OWN TRADITIONAL TIMES AND MOVED OVER TO ‘RAILWAY TIME’.”

The early railway companies were of course not the first organizations to issue tickets, but they were soon the most prolific of ticket sellers by quite some margin. Additionally, their tickets were likely to be the first examples that many people had ever encountered. Newcomers to the system were often taken aback – even offended – by being asked to produce the paper proof of their purchase. They had paid in good faith and now here was someone questioning their right to travel and even their honesty – or so it seemed.

“THE WEALTHIER AND MORE WELL KNOWN A PERSON WAS, THE LARGER WAS THE AREA IN WHICH PEOPLE WOULD PROVIDE SERVICES ON CREDIT.”

Indeed, in the first half of the nineteenth century, even the idea of paying cash up front was not all that familiar. Most day-to-day purchases were carried out on credit. People patronized a small number of trades’ people and kept an account with each that was settled periodically. This is why, for example, Mrs Beeton in her famous housekeeping manual advised keeping accurate records of all deliveries from butchers and grocers and checking them off against their later bills. Credit arrangements in the early nineteenth century were not restricted to food shopping. The wealthy, in particular, kept accounts at their tailors and dressmakers, milliners, shoemakers and jewellers, as well as at the local hostelries and stables. A stranger arriving in town of course might well be expected to pay up front in cash, but the wealthier and more well known a person was, the larger was the area in which people would provide goods and services on credit. The wealthy gentleman, the local factory owner or the member of parliament turning up at a railway station might have been tempted to wave off other requests for payment with an airy ‘put it on my account’ – but the railways did not run accounts, they sold tickets…

The railways were at the forefront of new ways to do business, and selling tickets was but one example of many. Requiring payment up front and administering that payment in a bureaucratic, impersonal way was a very modern approach, and many people had to be coached through the process.

‘All preliminary words are not only a waste of time, but quite unnecessary; the clerk sits at the counter for the purpose of ascertaining the place you are bound for, the class you wish to travel by, and the nature of the journey, whether single or double. The readiest way, therefore, of making yourself understood, is to apply for your ticket somewhat after this manner, ‘Bath – first class – return’, or whatever it may be.’

This was the advice given in the Railway Traveller’s Handy Book of 1862. The manual also took pains to point out that ‘the ticket is a voucher that the traveller has paid his fare, and its non-production at the end of the journey entails the necessity of paying a second time.’

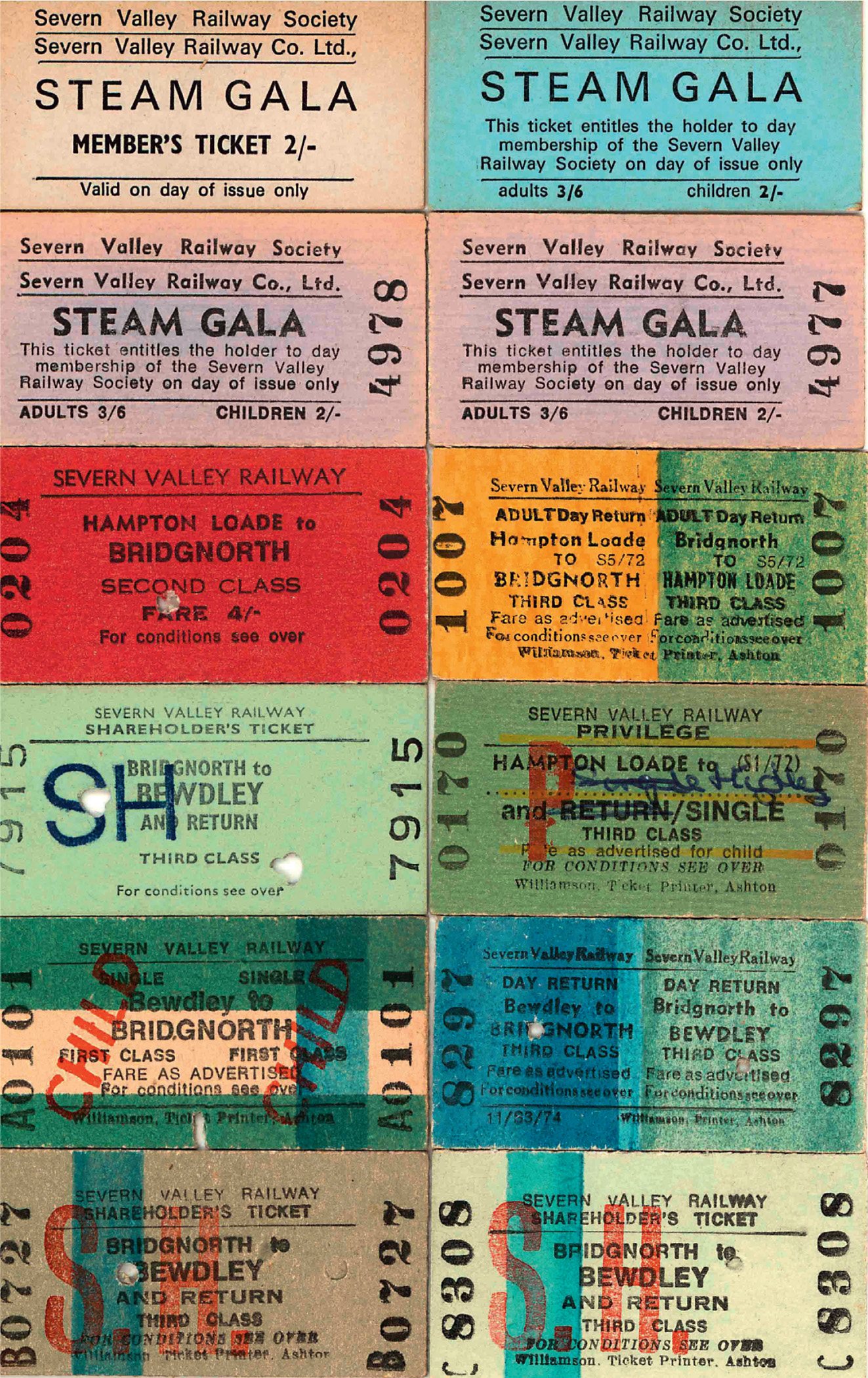

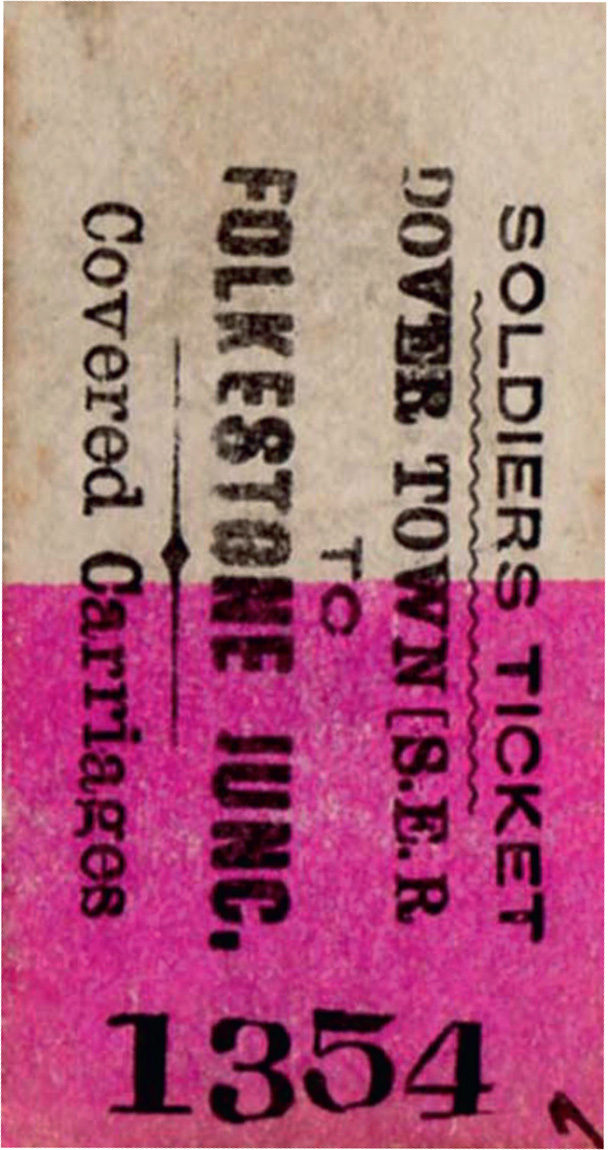

The first tickets were, like those of the stagecoach, handwritten receipts made out individually by the ticket clerk. Issuing the tickets was a time-consuming process. Coaches carried around a dozen passengers, but trains could transport hundreds and slow ticketing soon became a problem, with long impatient queues developing at popular stations. The handwritten system also offered unscrupulous ticket clerks an opportunity to defraud the railway companies by claiming, for example, to have sold thirty tickets when they had in fact written out thirty-five, and then pocketing the money from the additional five. The solution to the problem, and one that was to serve for 150 years, was put together by Thomas Edmondson. He was a trained cabinet-maker who managed to get one of the first station master jobs on the Newcastle and Carlisle railway, although interestingly it was the Manchester and Leeds Railway that first took up his idea. The idea was simple enough: sequentially numbered tickets – but Edmondson used existing technology to create the new system affordably and reliably. He began with a uniform size and shape of ticket, so that they could all be processed by the same machines. The size does not sound particularly standard now – one and seven thirty seconds of an inch wide by two and quarter inches long and one thirty second of an inch thick – but it worked. These are not numbers that roll off the tongue, but they fitted the commercially available pasteboard stock, could be printed by small manageable printing presses and yet were large enough to carry all the pertinent information. Each station required its own specially printed ticket stock of many different types. Each local destination, and the more popular distant stations, required a minimum of four differently printed tickets – child, adult, single and return. Where first, second and third class services were offered, the number of tickets needed could rise to as many as twelve pre-printed types per destination.

“THE FIRST TICKETS WERE, LIKE THOSE OF THE STAGE COACH, HAND WRITTEN RECEIPTS.”

Each separate type of ticket to and from each pair of stations was numbered in sequence, beginning with the first ticket ever issued, reading 0001. Controlling so many different types of ticket required strict organization, but was not especially difficult. Each station, and at busy stations, each group of clerks, had a wooden ticket rack with each of the ticket types carefully labelled. The numbered tickets were loaded into the rack in order and used in strict number rotation, so that 0456 followed 0455, and so on. In addition to a serial number, each ticket had printed upon it the origin and destination, the class of travel and whether it was for an adult, a child, a single or return journey. Colour bands, typefaces and occasionally other graphic images helped people to quickly differentiate between types, and as each ticket was issued it was date-stamped with the day of travel.

Edmondson’s pasteboard tickets first went into service in 1840 and only two years later became standard right across the industry, employed by all the railway companies. They survived the myriad of company mergers that gradually reduced the number of companies down to what became known as ‘The Big Four’ in the early twentieth century and even the nationalization of the network to become British Rail in 1948. Indeed, Edmondson’s tickets were only replaced after the new APTIS ticketing system (short for Advanced Passenger Ticket Information System) was introduced in 1986, just as I began my own brief railway career. I arrived as a newly minted ticket clerk to find a shiny new machine in place, printing out thin card tickets with an orange band at both top and bottom. Meanwhile, the cupboard at the back of the office was still chockfull of unused Edmondson pasteboard ticket stock.

THE ROYAL MAIL

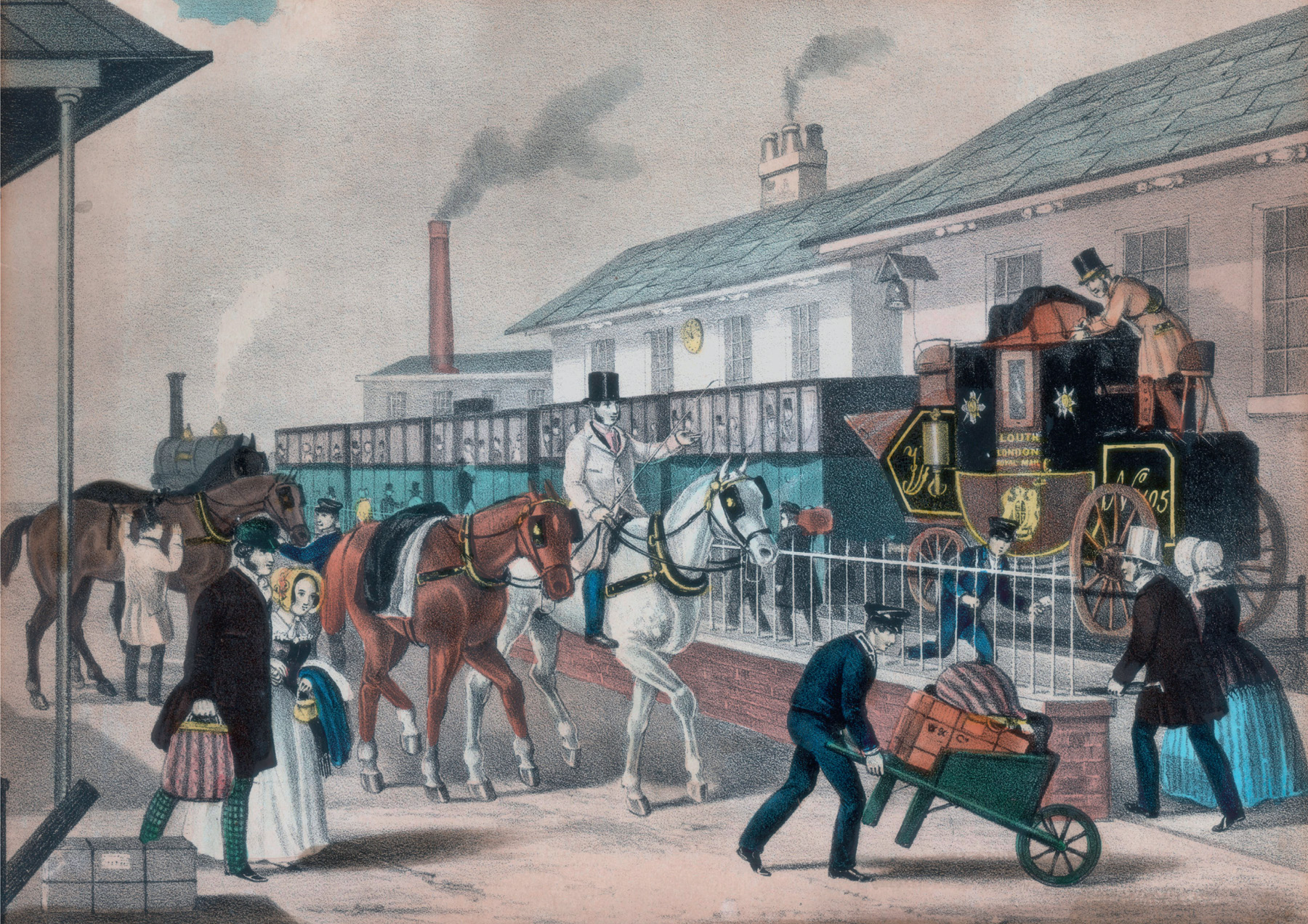

Internal communications aside, the railways were vital conduits of the nation’s correspondence from 11 November 1830, when the first Royal Mail consignment travelled along the Liverpool and Manchester line. The Post Office valued both speed and security and the railway was able to offer both. Until that November day, the Royal Mail had been limited to the speed of a coach and horses – seven to eight miles per hour in summer when the roads were dry and around five miles per hour in the muddy winter months. The mail coaches ran along regular routes at regular times and made easy pickings for highwaymen. Security came in the form of a guard dressed in a bright red coat and a tall black hat, armed with a pair of pistols and a blunderbuss. He was also equipped with an adjustable timepiece, a notebook to record the arrival and departures, and a large brass horn that he could sound to tell toll-gate keepers to open up in plenty of time to let the mail coach through at speed. Stops en route to change horses were slick affairs that were timed to the second, while mailbags were loaded and unloaded. Mail for intermediate places was flung off the coach whilst on the move, with new bags snatched from the outstretched arms of the local postmaster. It was as speedy and reliable a service as good organization and resources could achieve in a horse-drawn world. Letters could move from Bristol to London in just sixteen hours at a cost of around 4d.

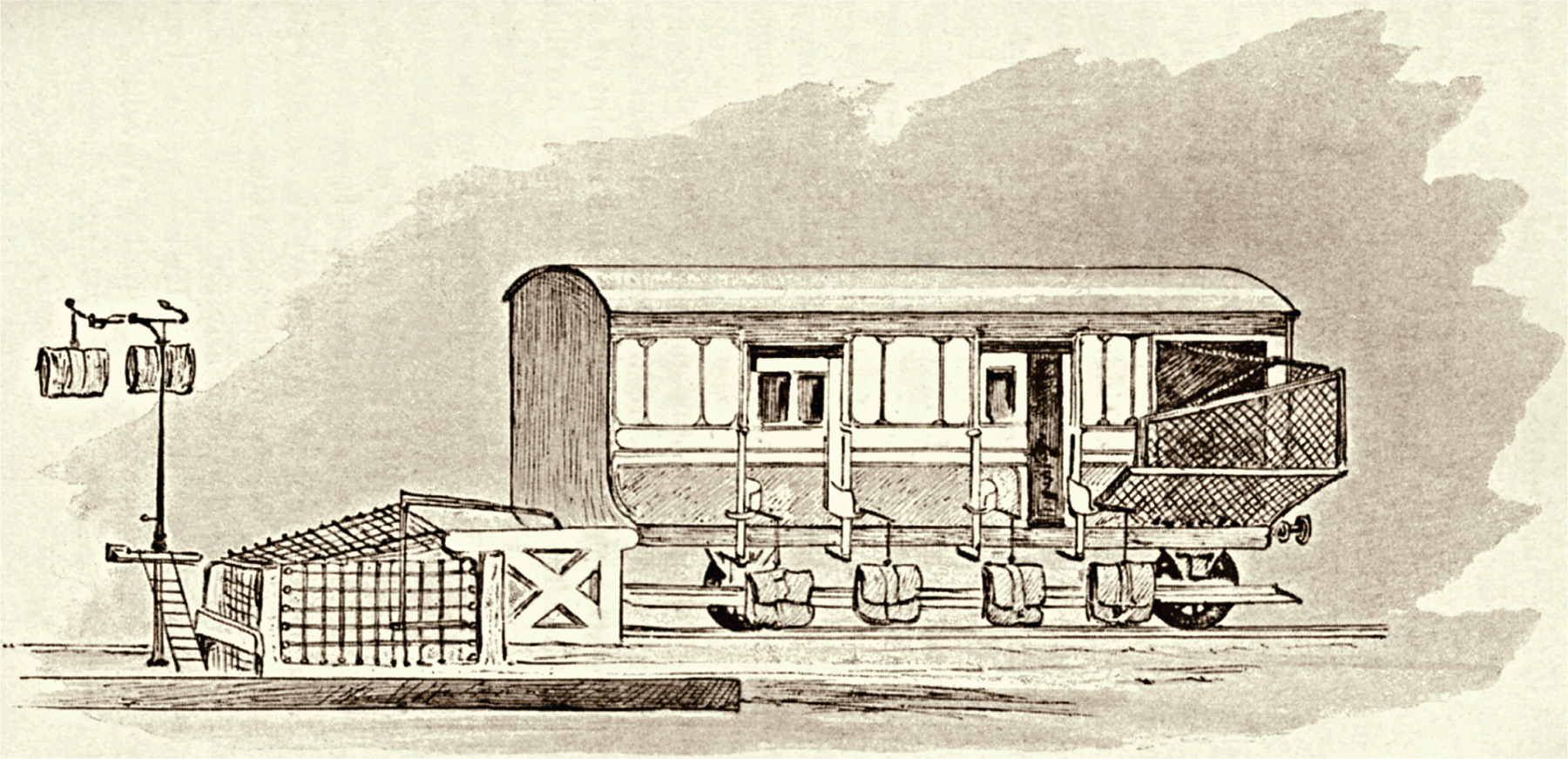

The introduction of the railways made an almost instant impact on the way that mail was delivered nationwide. Wherever the new lines ran, the mail coaches rolled to a halt. By 1846, the last of the coaches pulled out of London bound for Norwich. A few hung on a little longer on cross-country routes as yet unserved by suitable lines, but the echoes of the post horn were fading fast. Safely tucked into fast-moving, sturdy lockable wagons the Royal Mail could move at over double the speed. There was another benefit to railway transport, too – the possibility of processing that mail en route.

The first experiment with a travelling post office took place in 1839 between Birmingham and Warrington, upon the Grand Junction Railway. Post office workers sorted the mail inside a converted horse wagon as they thundered along the new iron rails. This approach could cut several hours off the time it took to get a letter from sender to recipient. The traditional pattern of postal work was for the incoming letters to be gathered up in local centres and sorted by a worker into different packets, which were then dispatched in various directions. A travelling post office worked as a regional office gathering up the mail along its journey and sorting as it went, covering ground before anyone yet knew which packet it would finally end up in. By 1852, there were forty full-time clerks at work upon a number of routes criss-crossing the country. However, by then the whole nature of the post had changed as well – the stamp had been invented and the 76 million letters that were processed in 1839 had become a staggering total of more than 350 million.

THE PENNY BLACK

In the early part of the nineteenth century, letters were carried by the Post Office for free – at least, if you were an employee of a government office, a member of parliament or one of a small number of other fee-exempt groups. These included those letters carried on that first 1830 run. Otherwise, postage rates were charged that were based upon a rather complicated scale of weights and distances. The system was not cheap, either. The postal service was viewed as a moneymaking operation by the government – one paid for not by the sender of the letter, but by its recipient. Middle and upper class letter writers tried to keep their costs down by writing in very tiny handwriting and using every tiny available space on the paper. Many letters were ‘cross-written’, wherein they were first written on with the paper one way up and when the page was full it was turned ninety degrees and written on again over the top. The resulting spiderlike text could be deciphered by holding the paper first one way then the other. The working classes almost never sent letters at all.

A rationalization of the postal pricing policy began in 1839. This involved the complete abolition of the free carriage of mail and introduced significantly cheaper flat rates. On 10 January 1840, the service became known as the ‘Penny Post’ and in May of that year the world’s first stamp was issued. This was a pre-paid voucher that could be easily affixed to the letter, entitling it to carriage by the Royal Mail from anywhere to anywhere else in the country. The reform of the system was masterminded and directed through the political jungle by Sir Rowland Hill assisted by Henry Cole, who both seem to have approached the business of revolutionizing the national mail system in the context of a great social reform. Many of the old guard were horrified, claiming that even enormous growth in the volume of mail could not compensate in revenue for the new, cheaper postage rate. These doubters had a point – it did indeed take stupendous growth over as long as thirty years to return to the previous level of revenue income. However, Sir Rowland Hill was looking beyond pure commercial concerns; he had an unprecedented vision of the mail as a public service that would facilitate business and personal communications, connecting Britons everywhere for the good of all.

The idea for the postage stamp was drawn in part from a system used by the tax departments of government, in which taxed goods such as paper or newspapers were ‘stamped’ to prove that they had been assessed and the attendant duty paid. The ‘Penny Black’, as the new stamp was to be known, would carry the word ‘postage’ across the top to highlight that this was not a tax stamp. Initially, Sir Rowland Hill sought a design for the stamp by holding a competition, but the results were disappointing, as none of the potential designers seemed to grasp what was needed in order to prevent fraud whilst maintaining easy recognition.

PENNY BLACK, PENNY RED

The first Penny Blacks were printed in sheets without perforations and had to be cut out with scissors. They also proved rather easy to re-use fraudulently. So, just one year after its groundbreaking release, the Penny Black was replaced with the Penny Red, upon which the post office franking showed up more easily.

However, by then over sixty-eight million Penny Blacks had been printed and the British public had taken to the whole system with great enthusiasm. For the first time the Royal Mail had become truly accessible – even to the working classes – meaning that a true communications revolution had come about. As Victorian literacy levels increased rapidly, the introduction of cheap stamps, combined with an easy to understand system and speedy secure railway transport, meant that information flowed across the country as never before.

In the end, Hill came up with something himself. His design was based upon an engraving of the young Queen Victoria, which had in its turn been taken from a portrait made of her some years earlier, when she was still a princess and just fifteen years of age. It was a distinctive profile image that needed no further explanation. Ever since then, British stamps have used a profile of the reigning monarch as their standard design. Other nations that subsequently copied the idea of a pre-paid, single flat-rate postal system have all put the name of their nation upon their stamps, but for British stamps the image of the reigning monarch is still considered to be sufficient as a means of identification.

“BOTH IN WAR AND PEACETIME, LONDON WAS THE MAJOR HUB OF THE DAILY POSTAL OPERATION.”

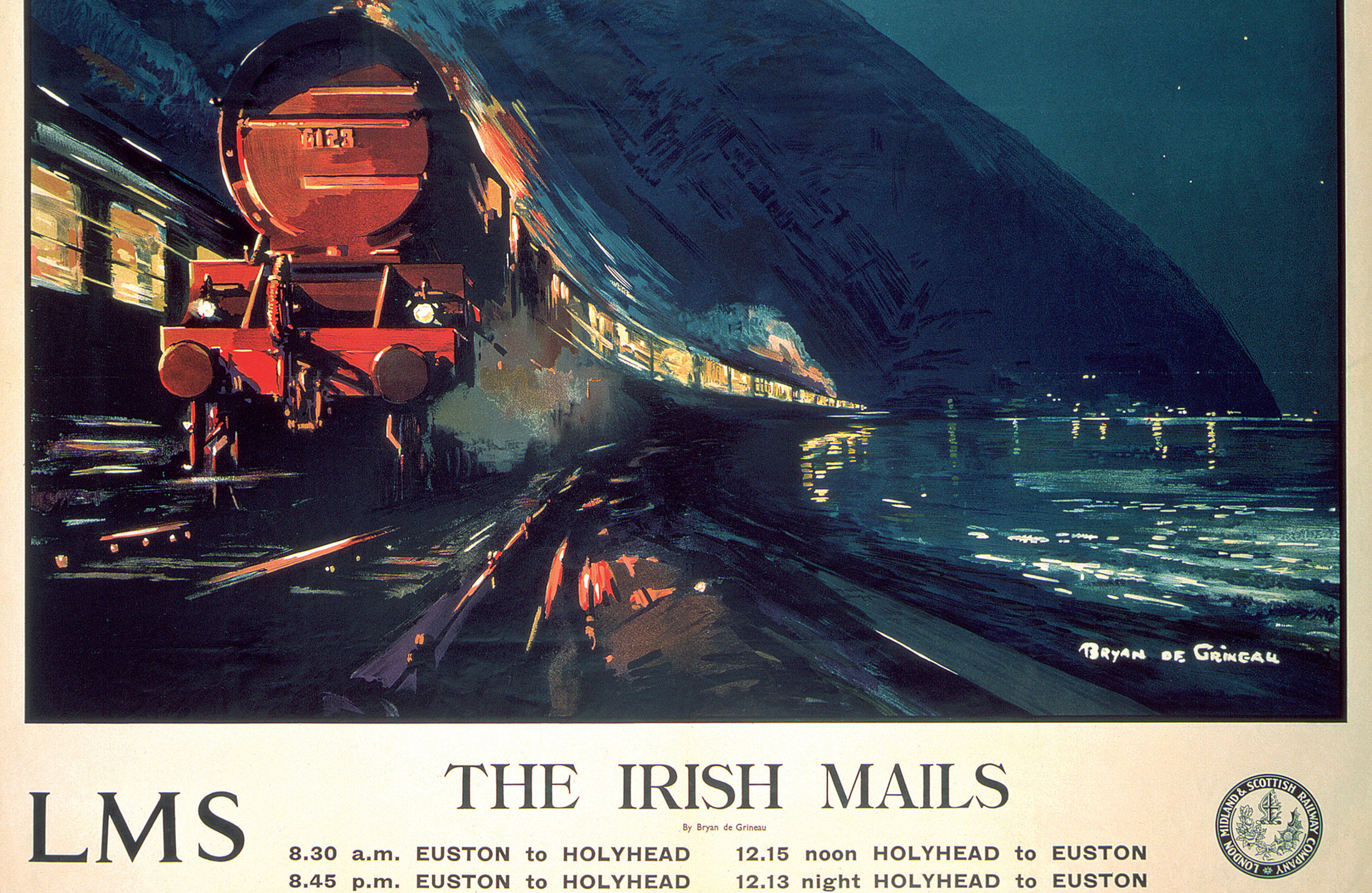

The heyday of the Travelling Post Office (TPO) came in the years surrounding the First World War. The postal sorting vans ran on 130 separate routes both by day and night nationwide, and as war began to send sons, fathers and brothers far away from home, the mail trains became central to more people’s lives than ever before. Twelve and a half million letters per week arrived from all corners of the country to a specially built sorting office at Regent’s Park, London, before a shuttle of trains carried them down to the ports. The Army Postal Service brought back treasured replies from loved ones fighting abroad. Despite fears about the leaking of sensitive information and the effects of bad news upon morale back home, there was never any doubt in the government’s mind that the mail had to get through. Seventy-five years on from the introduction of the Penny Black and the beginning of railway-carried mail, the population of Britain had become wedded to the idea of keeping in touch. Silence from distant friends and family was unthinkable.

Both in war and peacetime, London was the major hub of the daily postal operation. The evening’s mail was gathered from all over the capital and was then despatched across the regions overnight, ready to be delivered in time for breakfast the next day. Day mail trains carried post between the more distant parts of the country, often bringing it down to London for re-sorting and speeding out again in time for an afternoon delivery. At this time, most towns and cities had two mail deliveries a day. However, central London enjoyed four, with a few favoured business-orientated areas having as many as six separate deliveries of mail a day. In the central business areas of the city, it was possible to hold entire conversations by post in a single day, almost rivalling the speed and convenience of modern email.

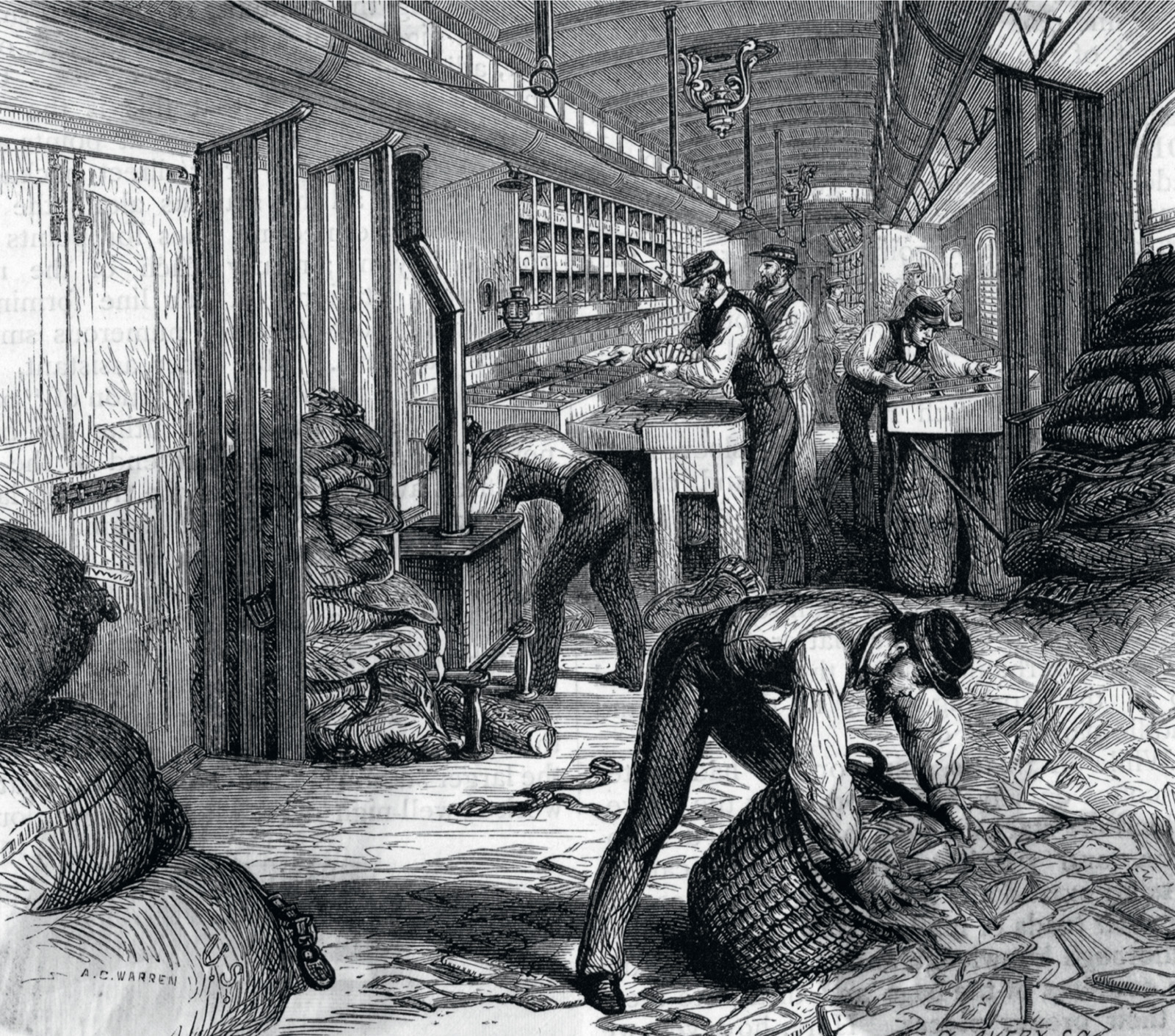

As mail was emptied out of post-boxes up and down the country, a preliminary rough sorting took place locally that separated it out into basic regions. The mail was packed into stout leather pouches, weighing anything from twenty to sixty pounds. The pouches were sent to the station, where they were joined by other pouches from other local offices and bundled together into mail sacks. The sacks were then hauled onto the relevant train and the journey began.

Inside the TPO, wooden racks lined the walls, with a narrow waist-high bench running in front of them. The clerks mostly stood to do their work, giving them the reach required to work at speed, slipping letters into an array of a hundred or more pigeon holes in front of them. Each carriage on a dedicated mail train processed the letters for a different area, so as sacks arrived, labels were carefully examined. Some would be sent to the other end of the train while others were opened and pouches then ferried to the correct section. The work involved a lot of heavy lifting on a moving, jerking train.

Sorting clerks had to memorize all the postal districts on their routes and know which local office handled which. Incomplete addresses required prodigious local knowledge of the geography of the country and the organization of the postal system, if they were to be correctly sorted. Despite the difficulties of working on a moving train, clerks processed an average of 2,000 letters each per hour at an accuracy rate of ninety-nine per cent, while working under great pressure. It was relentless work. The lighting was frequently inadequate, the heating temperamental and catering facilities somewhat rudimentary. But TPO staff had a reputation for camaraderie. As the train thundered through the countryside, mail sacks were picked up and dropped off en route. By the early twentieth century, the sacks were generally thrown off the train without it even stopping.

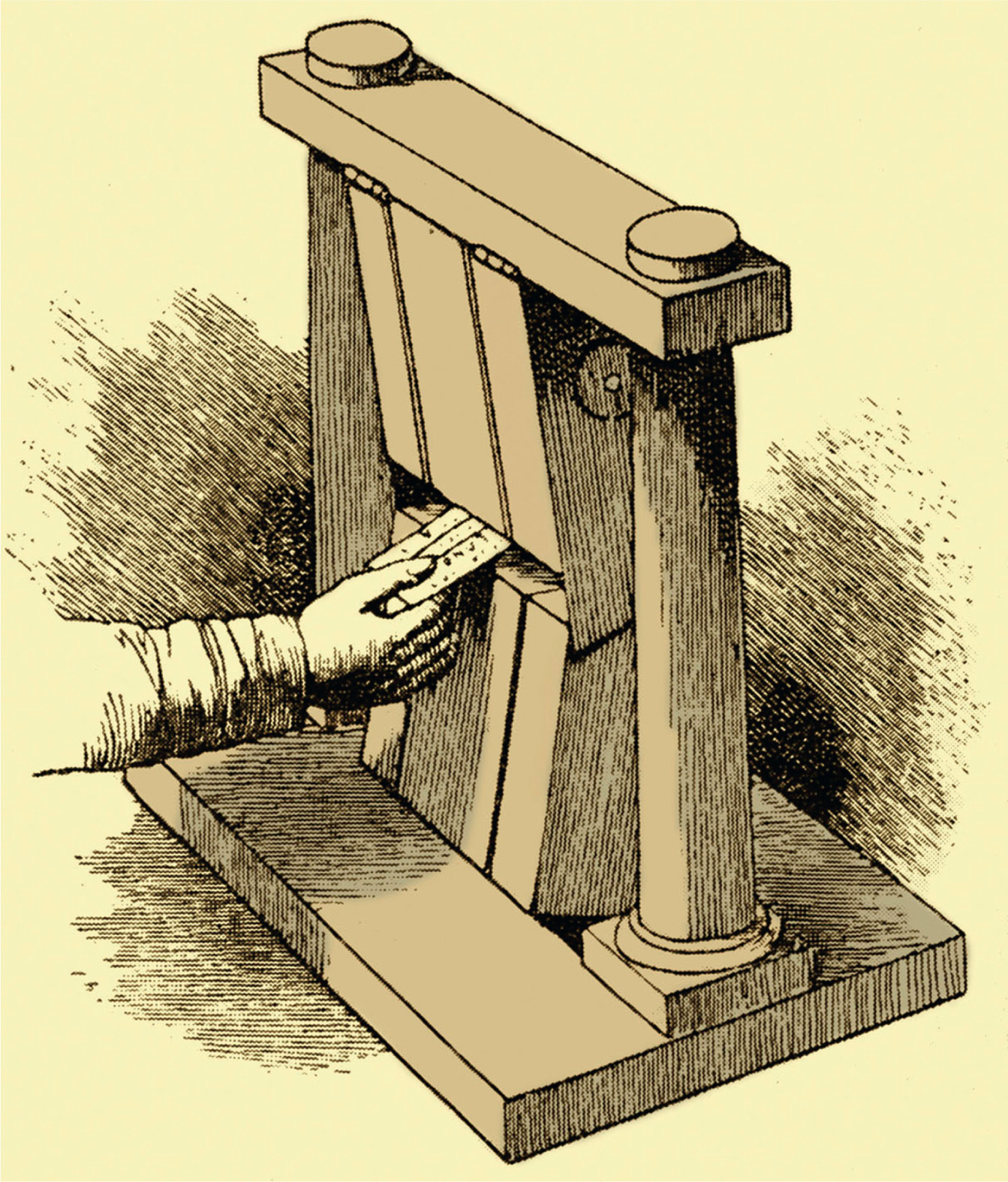

The year 1886 had seen the invention of ‘the apparatus’. Each TPO carriage was fitted with an extendable net next to a door. Local postmasters hung their mail bags on hooks at specified places on the trackside, and as the train approached the staff on board extended the net, whisking up the sack as they passed and dumping it inside the carriage with some force. Sorted mail being dropped off along the way was attached to an arm that extended three feet out to the side the carriage. A net on the trackside caught the sack as the train whipped past. The whole operation was heavy, fast and distinctly scary. Many postal workers preferred to keep their distance. Collin Mellish worked with the same system in the 1960s and describes the procedure as follows:

‘The postman who was at the back of the train used to look out of the train and he’d know every sort of mark and house and tree.... and then, where the pickup point was there was a white board on the side of the track... he used to ...push the lever down on the side of the train, and this net used to come out and it’d take… maybe thirty seconds to a minute after that before it picked up the actual mail bags.’

Mellish also recorded the common practice of postal workers keeping one net outside the train for the whole journey. This was kept full of milk and kippers and was used as a sort of communal fridge. This was the world of W. H. Auden’s famous poem ‘The Night Mail’ and the short film of the same name that it was written to be part of:

This is the Night Mail crossing the border,

Bringing the cheque and the postal order,

Letters for the rich, letters for the poor,

The shop at the corner and the girl next door.

Pulling up Beattock, a steady climb:

The gradient’s against her, but she’s on time.

Past Cotton-grass and moorland boulder

Shovelling white steam over her shoulder

Snorting noisily as she passes

Silent miles of wind-bent grasses.

The film was produced by the GPO film unit in 1936, with the poem written by Auden to match the graphics. Benjamin Britten wrote the score, again to match the footage. Both the music and the poem, as well as the narrator Stuart Legg, all matched their tempo to the sounds of the train. If you have ever travelled on or behind a steam locomotive, you will know how uncannily accurate the whole work of art is. The first four lines sound like an engine on the flat gradually picking up the pace, then almost with a start the beat changes, ‘pulling up Beattock’ slow and laboured, almost panting, as suddenly the engine is working much harder to haul us up. Gradually, the speed returns and the rhythm relaxes, as the summit is reached and we are sailing steadily easily on.

The film was a celebration of the whole working life of the TPO with later verses, still set to the rhythm of a speeding train, listing the huge variety of mail, personal and business, trivial and earth-shattering, that the train carried through the night.

However, thirty years later the moment had passed. The ‘apparatus’ saw its last use in 1971, as the increasing speeds of trains made it too dangerous to use. However, by then the travelling post offices were also in steep decline, as road transport finally became quick and reliable enough to take advantage of its greater coverage of the country. Soon mail lorries took over route after route, just as once upon a time the railways had taken over from the road-based, horse-drawn coaches. The last TPOs limped into the twenty-first century over a hundred and seventy years after that first experiment was conducted in a converted horse-wagon on the Birmingham to Warrington railway line.

THE NEWS

Newspapers were a big part of the very first mail to be transported by train. In the early years of rail travel, every newspaper printed had to be conveyed, before sale, to a revenue office, where it was taxed and a revenue stamp applied. This ‘stamp duty’ entitled the newspaper to free carriage by Royal Mail as many times as people wished. Therefore, many of these early newspapers had multiple readers spread out across the country, as people sent them onto their friends – which was probably just as well, because they were quite pricey articles. In addition to the stamp duty, newspaper proprietors had to pay tax upon the paper and tax upon newspaper advertising, more than doubling cover prices. For example, in the course of 1851 The Times paid around £66,000 in stamp duty, £17,600 on paper duty and £24,000 on advertising duty. Printing technologies were also slow and laborious, which both added to the costs and limited the size of each newspaper print run. However, despite all this, newspapers were exceedingly popular. Around fifty separate titles were published in London at this time and a further hundred were spread across the rest of the country. The Times was the leading London paper by quite some margin, and outside the capital the Manchester Guardian (later to become just the Guardian) was by far the most well known, even enjoying an international reputation. Circulation numbers were necessarily fairly small – even for the big players – and positively tiny for most of the other titles, which might have total readerships of less than a thousand. However, the railways, from the very first mail run, offered new opportunities for expansion. It was primarily the London papers, and especially The Times, that were able to make the most of fast regular railway transport to expand their customer base. They did this by extending their readerships out into the provincial towns and cities, sending parcels of newspapers out early in the morning along the rails to regional wholesale newsagents.

In 1855, the stamp duty and newspaper advertising duty were removed after a long and bitter political campaign. Newspapers could still choose to pay a reduced form of the stamp in order to secure postage rights, but equally they were free not to. The London and North Western Railway, the Midland Railway and the Northern Railway Company all introduced a newspaper parcel carriage service that year at three farthings per pound weight, in an attempt to hang on to and indeed expand their newspaper business. It was a shift that favoured the new breed of wholesale newsagent, men like W. H. Smith. All along those newspaper-carrying lines, hawkers and news stalls now graced the platforms, trying to catch a new market of people on the move with nothing much else to do but stare out of the window. These newspaper wholesalers also supplied parcels of papers to the hinterland of booksellers and newsagents beyond the stations.

“THE TIMES WAS THE LEADING LONDON NEWSPAPER BY QUITE SOME MARGIN.”

Once the tax was removed, competition between news titles boomed. A whole raft of new dailies appeared, many of which collapsed almost as soon as they had opened. Of these, The Telegraph, with its emphasis on price (1d per copy), was the biggest long-term success, becoming a realistic rival to The Times. In 1861 the paper duty was also repealed and newspaper prices fell even further. Huge choice and cheap prices spread the news-reading habit ever wider. Wherever the railway network went, London newspapers went too, gradually chipping away at the profitability of local titles. As sales expanded nationwide, London-based journalists finally began to expand their own horizons, travelling along the same lines in search of national rather than purely London-based stories. The spread of the railways also permitted the provincial papers to gather news directly from the capital rather than relying upon regurgitating copy from old London papers. Before the railways, a London paper would inevitably be at least a day old by the time it got to Manchester and two or three days old in Glasgow. This meant that the provincial papers, whilst hot on local topics, served up only rather tired and old news from London, by feeding off the out-of-date papers from the capital. Now for the first time national daily news became the norm nationwide, as parcels of newspapers hot off the presses sped through the night on the railways of Britain.

By the end of the nineteenth century, technical innovations in printing presses and typesetting allowed the papers to ramp up their output. Free schooling for all, with the attendant improvements in public literacy, broadened the potential market for cheap newsprint still further. Gone were the days when newspapers were the preserve of the wealthy and the educated male elite. People from all walks of life were now potential customers, and journalists, editors and newspaper proprietors alike were adjusting their styles accordingly. For example, the Daily Mail was just one of another raft of new titles seeking to target new sectors of the public. The owners aimed their new paper at a lower middle class readership and, in a groundbreaking shift, at female readers, including dedicated articles upon subjects that they thought ‘suitable’ for women.

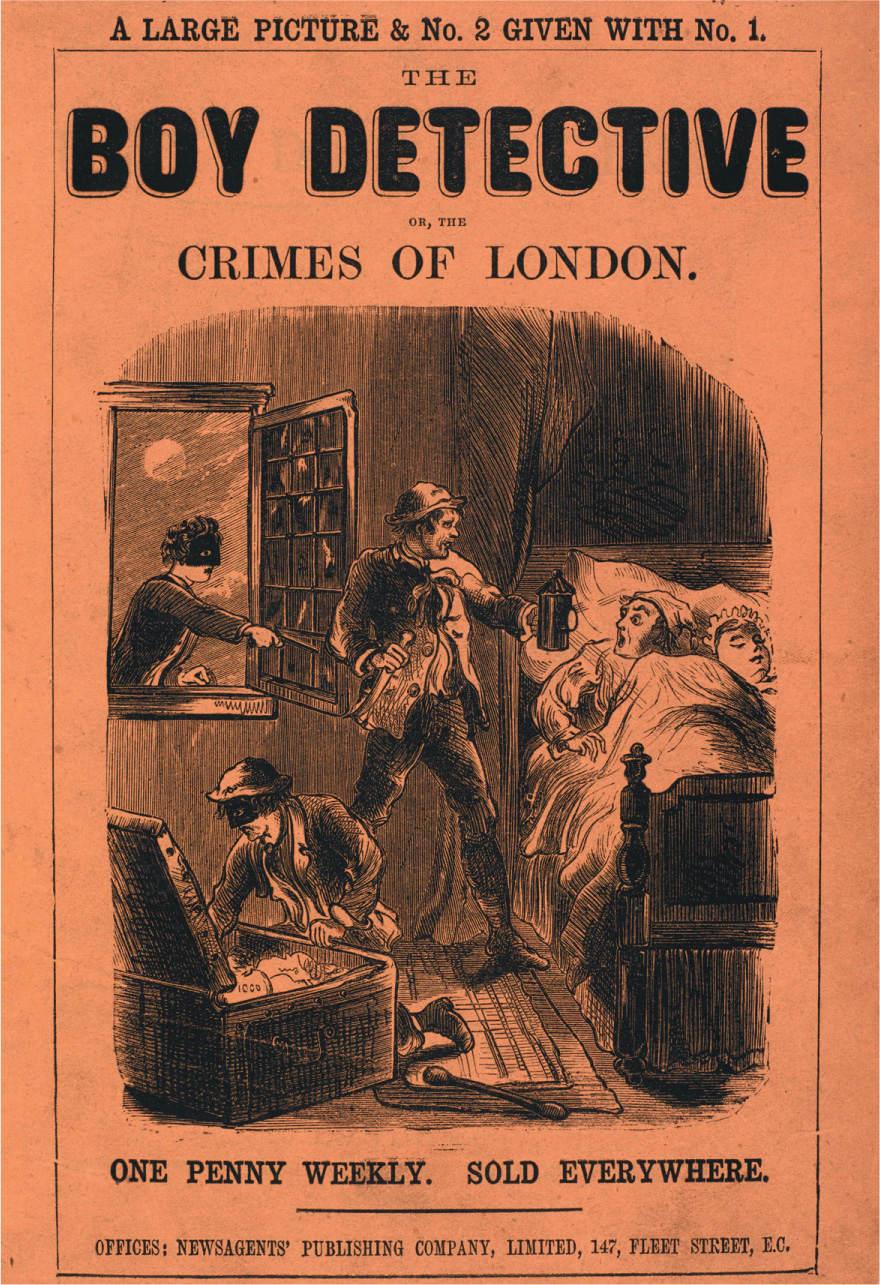

Several magazines aimed at women had appeared previously, which generally featured romantic fiction, fashion and cookery, but this was the first time that specifically ‘feminine’ content had formed part of a newspaper. Crime reporting formed the backbone of another batch of titles, aimed more at a working class readership. These featured remarkably blunt and lurid language. Many of these papers remained as weeklies rather than dailies, reflecting the scarcer resources of their customers. They came to be known disparagingly as ‘penny dreadfuls’. Sports news papers, and sporting sections within other titles, were undergoing a particularly rapid change. Before 1900, most of these were concerned with fox hunting, race meets, boxing matches and cricket. While both the horse racing and boxing attracted a following at the lower as well as the upper end of society, the sporting papers generally served a well-heeled audience. However, by the end of the century new mass spectator sports, football in particular, were very rapidly gaining in popularity among the less well off. As a consequence, sports papers radically shifted their coverage and tone.

“A WIDE RANGE OF JOURNALS AND MAGAZINES TRAVELLED ALONGSIDE ALL THE NEWS PAPERS.”

As far as the railways were concerned, newsprint was an excellent freight customer. Complete, dedicated ‘newspaper specials’ headed nightly out of London, loaded to the gunnels and bound for all corners of the nation while catering for all literary tastes. It was not quite all one-way traffic, though: another newspaper special left Manchester packed with copies of the Manchester Guardian destined for Yorkshire, and along with several other provincial papers moved large consignments from their home offices into the capital. By the 1930s, it was estimated that two thirds of the entire British population read a newspaper every day.

A wide range of journals and magazines travelled alongside all the newspapers. These included political satires, women’s magazines full of household hints, and even specialist publications such as The Quiver, which carried long articles about bible study and was aimed at devout non-conformist families. Even Charles Dickens ran his own magazine, Household Words, for which he wrote most of the articles himself. The cheaper production costs combined with the expanded markets offered by railway distribution fuelled a boom in all manner of cheap press. Just as the newspapers discovered that new sectors of the population were increasingly able to afford and able to read their offerings, the magazine market was discovering new potential buyers. Increasingly, ‘specialist’ interests could be profitably catered for, and the subject matter of the new magazines became ever more eclectic. Magazines suited railway travel almost as well as newspapers, as they provided reading material that was cheap and broken into small digestible segments that could be dipped in and out of according to the rhythm of travel. This explosion of accessible print was perhaps more visible upon station platforms than anywhere else, with titles of all descriptions massed together on open-fronted wooden stalls.

William Henry Smith had set up as a newspaper distributor in the days of mail coaches. He had almost entirely cornered the market in carrying titles out of London, when the railways arrived to offer him an alternative form of transport. In 1848, Smith negotiated an exclusive deal with the London and North Western Railway to operate all the stalls upon their stations. A host of small independent stallholders were swept away, book trade staff were drafted in and a moral purge of the merchandise took place. Out went the lurid tales of ‘bloody murder’ and in came respectable family titles.

“ALL THREE OF THESE RAILWAY PRINT SELLER ENTREPRENEURS SOON FOUND THAT BOOKS SOLD WELL ON STATION PLATFORMS.”

Other railway companies liked the look of these new W. H. Smith and Son stands, and soon Smith dominated the entire English railway station network. John Menzies was to copy the model and found an equally dominant presence in Scotland, while in Ireland W. H. Smith was eventually bought out by his general manager, Charles Eason. All three of these railway print seller entrepreneurs soon found that in addition to newspapers and magazines, books sold well on station platforms. Cheap fiction was where the main profit lay, rather than in heavy factual works – although the new print entrepreneurs continued to hold the line against ‘offensive’, ‘indecent’ or ‘obscene’ literature. Commercial upheaval within the publishing world had significantly dropped the price of reprints, allowing firms such as John Murray to publish his ‘reading for the rail’ series as ‘cheap books in large readable type’. George Routledge produced a series in green covers collectively known as his ‘railway library’ and, seeing which way the wind was blowing, W. H. Smith went into business with Chapman and Hall to produce the ‘select library of fiction’, all with shiny covers and yellow backs. These innovative sellers had unlocked a whole new audience for novels, particularly as for much of the second half of the nineteenth century Smith’s also offered a library service for rail travellers. By 1866, 177 separate stalls held stocks of books for loan to regular customers, and special requests could be brought in from other stalls ready to be picked up the following day. This was a particularly convenient arrangement for commuters, although many members of the public who did not use the railways joined the library scheme as well, borrowing and returning books to their local station. Novel reading, which had been the preserve of the elite, became an affordable habit enjoyed by people from almost all social classes.

THE ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH

‘If only one collision of a passenger train with its sickening accompaniments of suffering, to say nothing of its heavy expenses, were prevented by free use of the telegraph, the immunity would be cheaply attained, and the cost of the improvement be amply compensated.’

So opined Mark Huish, the general manager of the London and North Western Railway, in 1854.

The electric telegraph first emerged as a commercial proposition in the early years of the railways, and indeed the railways were to be its first customer. In 1837, when the ink was still wet upon their patent, William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone persuaded Robert Stephenson (son of George) to trial their new communication device between Euston and Camden Town, on the London to Birmingham line that he was then constructing. The incline out of Euston was initially too steep for locomotives, so this first section of the journey was to be achieved by using a heavy static engine at Camden Town and a long rope to haul the carriages along the track. A system was needed to tell the men tending the engine when to begin the pull. Cooke and Wheatstone had created a pair of devices linked by wires by which a message could be spelled out at one end by moving a needle to point to letters, and received at the other end by recording the position of the needles. The signal sent lasted only momentarily, so a clerk needed to be on hand to watch the apparatus and note the positions of the needles down in a notebook. However, despite the complexity of the system, it provided near-instant communication over considerable distances. Robert Stephenson decided in the end to stick with the older technology of pneumatic tubes and semaphore, but the Great Western railway had been watching keenly, and it was on their line between Paddington and West Drayton that the telegraph entered productive service the following year. Up to fifteen words per minute could be transmitted, but for the railways the importance of this new technology came not with the ability to transmit written words but with the potential to transmit signalling information.

We saw earlier how time was used to space trains out along the track (see here), but this system had a single major and deadly failing. If a train broke down or encountered any other difficulties on its journey along a section of track, it had no way of letting anyone behind know what had happened. At the regulation interval, a second train could be bearing down on the stranded train at speed. The solution suggested by Cooke was to use his telegraph to let people further along the line know whether a train had either entered or positively left an area. Nor did this have to be laboriously spelled out. Two simple positions for the telegraphic needle could show ‘line clear’ or ‘line blocked’. As a train entered a particular section of track, it ran over a device that sent a single signal up the line, causing the needle to twitch over to ‘line blocked’. The receiving signalman wrote down the exact time and the blocked nature of the signal in his book, and when that same train left the section of track at the other end, it activated a second signal twitching the needle to ‘line clear’, which again the signalman noted down. It was thus possible to know exactly where a train actually was on the line. And the wooden signal arms set atop their line side poles could be set accordingly.

The block system, as it came to be known, proved to be a major boon to safety and, in conjunction with the mechanical semaphore signal arms, formed the basis of signalling for around a hundred years. Cooke and Wheatstone’s devices were improved upon most notably by introducing a fail-safe element. In the original version of the system, the connecting wire was usually dormant, with a positive signal being sent as the train crossed the threshold. However, if a technical fault occurred, no further information would be sent, the driver would be none the wiser, and no one would know where exactly the trains had got to. By reversing the situation so that the line was positively charged when at rest and the signal was an interruption of that charge, technical faults would result in all signals turning to danger and stopping all movements – which was altogether a much safer situation. In parallel to the ‘block instruments’ with their twitching needles, many railway companies also installed the simple ‘bell telegraph’ version – generally a device that simply rang a bell at the other end of the line. The number of rings on the bell represented a code for certain information. Some of this was pure signalling safety information – such as two rings when a train entered a section, six rings for an obstruction on the line, or seven if the train was to be stopped immediately. Other codes were more for scheduling information, so that a signalman would know how to prioritize trains at different times. For example, a goods train loaded with perishable goods had a code of five rings that gave it priority over a goods train of coal wagons, which was notified by three rings. Initially, each railway had its own codes, but gradually over time a degree of standardization crept in. I was still required to memorize these codes in the mid-1980s, when I sat my own signalling exams for British Rail. One pause, two pause, four pause is a rhythm that still means to me ‘is it safe to send you a passenger train?’ the first ring being a sort of introduction to call attention, the two rings asking if the line is clear, and the four beats tells you what sort of train it is – in this case, a passenger train. If the track is not clear you give no answer, but if all is well then the rhythm is repeated back down the line, to show not only that the train can be sent but that you have correctly heard the request. Again, it is a system with a built-in fail-safe – silence meaning that all trains must stop.

In addition to improving safety, the telegraph provided a major efficiency saving for the railways by extending line capacity by ‘an incalculable degree’, according to the chief engineer of the London and North Western railway in 1851. The technology allowed the length of ‘sections’ to be considerably shortened. This meant that if only one train was allowed in any one section at a time, it was easy to see how more shorter sections allowed more trains to run upon the line at once. Nor was the electric telegraph a particularly difficult technology for the railways to install. Since they already owned the strip of land through which the lines ran, they simply had to erect wooden telegraph poles alongside to carry the wires. The robust simplicity of the system allowed for easy cheap maintenance and its operation required little in the way of staff training.

With signalling managed through simple codes and needle positions, the railway made little use of the telegraph’s ability to transmit words. However, their handy ownership of suitable strips of land allowed others to fully capitalize upon the invention. William Fothergill Cooke went into business with John Lewis Ricardo in 1845, setting up the Electric Telegraph Company, and negotiated with the various railway companies for the right to build his own telegraph wire system alongside their lines. It gave him access to an increasingly comprehensive network, one that his rivals later tried to negotiate with canal companies and for which numerous private landlords would have given their eye teeth. Naturally, the ELC offices were often located either within or next door to the stations along the line. Now personal travel, letter and parcel post and telegraph communications were all centred in the same buildings, representing an information and communication hotspot in communities. Additionally, the distances that that information could speedily travel were rapidly increasing. Charles Wheatstone (Cooke’s original partner and co-patentee) worked with Michael Faraday on insulating materials, and having found gutta percha to be particularly effective, suggested that coating electrical wires with the material would allow underwater cables to operate efficiently.

“IN ADDITION TO IMPROVING SAFETY, THE TELEGRAPH PROVIDED A MAJOR EFFICIENCY SAVING FOR THE RAILWAYS BY EXTENDING CAPACITY.”

By 1850, the first cable was laid across the English Channel, linking Britain with France. This great breakthrough in communications was followed in 1866, when Isambard kingdom Brunel’s ship the SS Great Eastern laid the first functional cable across the Atlantic Ocean, linking London with New York. Four years later, the first cable reached India. In 1848, it had taken around ten weeks to get a message from London to Bombay; by 1874, it took no more than four minutes.

None of the railway companies set out to bring political and cultural coherence to Britain, nor did they ever intend to facilitate the administration of the empire. However, they could probably not have imagined that they would change the nation’s reading habits completely or that they would foster an appetite for long-distance chat. Yet, inadvertently or not, that is exactly what they did. The railways helped the world to become more routine, businesslike and efficient, and at the same time they introduced new forms of personal communication and connection between people of all social classes.