XHTML

I’ve used some elements of XHTML (Extensible Hypertext Markup

Language) already in this book, although you may not have realized it. For

example, instead of the simple HTML tag <br>, I’ve been using the XHTML <br /> version. But what’s the difference

between the two markup languages?

Well, not a lot at first glance, but XHTML improves on HTML by clearing up a lot of little inconsistencies that make it hard to process. HTML requires a quite complex and very lenient parser, whereas XHTML, which uses standard syntax more like XML (Extensible Markup Language), is very easily processed with quite a simple parser—a parser being a piece of code that processes tags and commands and works out what they mean.

The Benefits of XHTML

Any program that can handle XML files can quickly process XHTML documents. As more and more devices such as iPhones, BlackBerries, and Android and Windows Phone devices (not to mention a plethora of new tablet devices) become web-enabled, it is increasingly important to ensure that web content looks good on them as well as on a PC or laptop’s web browser, and the tighter syntax required by XHTML is a big factor in helping this cross-platform compatibility.

What is happening right now is that browser developers, in order to be able to provide faster and more powerful programs, are trying to push web developers over to using XHTML, and the time may eventually come when HTML is superseded by XHTML—so it’s a good idea to start using it now.

XHTML Versions

The XHTML standard is constantly evolving, and there have been a few versions in use, but for one reason or another XHTML 1.0 has ended up being the only version that you need to understand.

While there have been other versions of XHTML (such as 1.1, 1.2, and 2.0) that have reached proposal stages and even begun to be used, none of them has gained much traction among web developers—that makes it all the more simple for you and me, as there’s only one version to master.

What’s Different?

The following XHTML rules differentiate it from HTML:

All tags must be closed by another tag. In cases in which there is no matching closing tag, the tag must close itself using a space followed by the symbols

/and>. So, for example, a tag such as<input type='submit'>needs to be changed into<input type='submit' />. In addition, all opening<p>tags now require a closing</p>tag, too. And no, you can’t replace them with<p />.All tags must be correctly nested. Therefore, the string

<b>My first name is <i>Robin</b></i>is not allowed, because the opening<b>has been closed before the<i>. The correct version is<b>My first name is <i>Robin</i></b>.All tag attributes must be enclosed in quotation marks. Instead of using tags such as

<form method=post action=post.php>, you should instead use<form method='post' action='post.php'>. You can also use double quotes:<form method="post" action="post.php">.The ampersand (

&) character cannot be used on its own. For example, the string “Batman & Robin” must be replaced with “Batman & Robin”. This means that URLs require modification, too: the HTML syntax<a href="index.php?page=12&item=15">should be replaced with<a href="index.php?page=12&item=15">.XHTML tags are case-sensitive and must be all in lowercase. Therefore, HTML such as

<BODY><DIV ID="heading">must be changed to the following syntax:<body><div id="heading">.Attributes cannot be minimized any more, so tags such as

<option name="bill" selected>now must be replaced with an assigned value:<option name="bill" selected="selected">. All other attributes, such ascheckedanddisabled, also need changing tochecked="checked",disabled="disabled", and so on.XHTML documents must start with a new XML declaration on the very first line, like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>.The

DOCTYPEdeclaration has been changed.The

<html>tag now requires anxmlnsattribute.

Let’s take a look at the XHTML 1.0–conforming document in Example 7-18.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd">

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xml:lang="en" lang="en">

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type"

content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<title>XHTML 1.0 Document</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>This is an example XHTML 1.0 document</p>

<h1>This is a heading</h1>

<p>This is some text</p>

</body>

</html>As previously discussed, the document begins with an XML

declaration, followed by the DOCTYPE

declaration and the <html> tag

with an xmlns attribute. From there

on, it all looks like straightforward HTML, except that the meta tag is closed properly with />.

HTML 4.01 Document Types

To tell the browser precisely how to handle a document, use the

DOCTYPE declaration, which defines

the syntax that is allowed. HTML 4.01 supports three DTDs (document type

declarations), as can be seen in the following examples.

The strict DTD in Example 7-19 requires complete adherence to HTML 4.01 syntax.

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd">The loose DTD in Example 7-20 allows some older elements and deprecated attributes. (The standards at http://w3.org/TR/xhtml1 explain which items are deprecated.)

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/loose.dtd">Finally, Example 7-21 signifies an HTML 4.01 document containing a frameset.

The HTML5 Document Type

For HTML5, using document types has become much simpler because there’s now just one of them, as follows:

<!DOCTYPE html>

Just the simple word html is

sufficient to tell the browser that your web page is designed for HTML5.

Further, because all the latest versions of most popular browsers have

supported most of the HTML5 specification since 2011 or so, this

document type is more and more likely to be the only one you need,

unless you choose to cater for older browsers.

XHTML 1.0 Document Types

You may well have come across one or more of the HTML document types before. However, the syntax is slightly different when it comes to XHTML 1.0, as shown in the following examples.

The strict DTD in Example 7-22 rules out the use of deprecated attributes and requires code that is completely correct.

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd">The transitional XHTML 1.0 DTD in Example 7-23 allows deprecated attributes and is the most commonly used DTD.

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd">Example 7-24 shows the only XHTML 1.0 DTD that supports framesets.

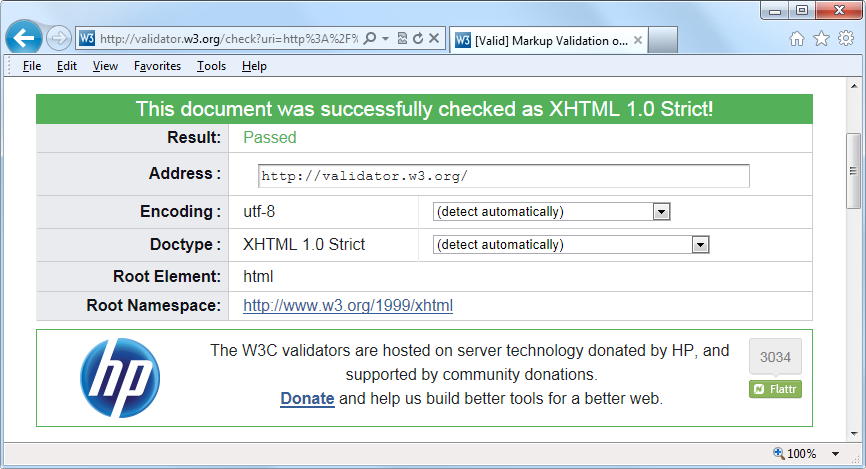

XHTML Validation

To validate your XHTML, visit the W3C validation site at http://validator.w3.org, where you can validate a document by URL, by file upload, or by typing it in or copying and pasting it into a web form. Before you code some PHP to create a web page, submit a sample of the output that you want to create to the validation site. No matter how carefully you code your XHTML, you will be surprised how many errors you’ve left in.

Whenever a document is not fully compatible with XHTML, you will be given helpful messages explaining how you can correct it. Figure 7-3 shows that the document in Example 7-18 successfully passes the XHTML 1.0 Strict validation test.

Note

You will find that your XHTML 1.0 documents are so close to HTML

that even if they are called up on a browser that is unaware of XHTML,

they should display correctly. The only potential problem is with the

<script> tag. To ensure

compatibility, avoid using the <script

src="script.src" /> syntax and replace it with the

following: <script

src="script.src"></script>.

This chapter represented another long journey in your task to master PHP. Now that you have formatting, file handling, XHTML, and a lot of other important concepts under your belt, the next chapter will introduce you to another major topic, MySQL.