Retrieving Submitted Data

Example 11-1 is only one part of the multipart form handling process. If you enter a name and click on the Submit Query button, absolutely nothing will happen other than the form being redisplayed. So, now it’s time to add some PHP code to process the data submitted by the form.

Example 11-2 expands on the previous program to include data processing. Type it in (or modify formtest.php by adding in the new lines), save it as formtest2.php, and try the program for yourself. The result of running this program and entering a name can be seen in Figure 11-2.

<?php // formtest2.php

if (isset($_POST['name'])) $name = $_POST['name'];

else $name = "(Not entered)";

echo <<<_END

<html>

<head>

<title>Form Test</title>

</head>

<body>

Your name is: $name<br />

<form method="post" action="formtest2.php">

What is your name?

<input type="text" name="name" />

<input type="submit" />

</form>

</body>

</html>

_END;

?>The only changes are a couple of lines at the start that check the

$_POST associative array for the field

name submitted. The previous chapter

introduced the $_POST associative

array, which contains an element for each field in an HTML form. In Example 11-2, the input name used was

name and the form method was POST, so element name of the $_POST array contains the value in $_POST['name'].

The PHP isset function is used to

test whether $_POST['name'] has been

assigned a value. If nothing was posted, the program assigns the value

“(Not entered)”; otherwise, it stores the value that was entered. Then a

single line has been added after the <body> statement to display that value,

which is stored in $name.

register_globals: An Old Solution Hangs On

Before security became such a big issue, the default behavior of

PHP was to assign the $_POST and

$_GET arrays directly to PHP

variables. For example, there would be no need to use the instruction

$name=$_POST['name'];, because

$name would be given that value

automatically by PHP at the program start!

Initially (prior to version 4.2.0 of PHP), this seemed a very

useful idea that saved a lot of extra code writing, but this practice

has now been discontinued and the feature is disabled by default. Should

you find register_globals enabled on

a production web server for which you are developing, you should

urgently ask your server administrator to disable it.

So why disable register_globals? It enables anyone to enter a

GET input on the tail of a URL, like

this: http://myserver.com?override=1. If your code

were ever to use the variable $override and you forgot to initialize it (for

example, through $override=0;), the

program could be compromised by such an exploit.

In fact, because many installations on the Web have this gaping hole, I advise you to always initialize every variable you use, just in case your code will ever run on such a system. Initialization is also good programming practice, because you can comment each initialization to remind yourself and other programmers what a variable is for.

Note

If you ever find yourself maintaining code that seems to assume

values for certain variables for no apparent reason, you can make an

educated guess that the programmer wrote the code using register_globals, and that these values are

intended to be extracted from a POST or GET. If so, I recommend you rewrite the code

to load these variables explicitly from the correct $_POST or $_GET array.

Default Values

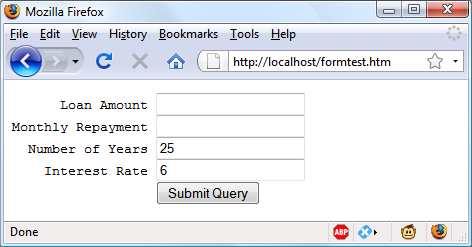

Sometimes it’s convenient to offer your site visitors a default value in a web form. For example, suppose you put up a loan repayment calculator widget on a real estate website. It could make sense to enter default values of, say, 25 years and 6 percent interest, so that the user can simply type in either the principal sum to borrow or the amount that she can afford to pay each month.

In this case, the HTML for those two values would be something like Example 11-3.

<form method="post" action="calc.php"><pre>

Loan Amount <input type="text" name="principle" />

Monthly Repayment <input type="text" name="monthly" />

Number of Years <input type="text" name="years" value="25" />

Interest Rate <input type="text" name="rate" value="6" />

<input type="submit" />

</pre></form>Note

If you wish to try this (and the other HTML code samples), type it in and save it with a .html file extension, such as test.html, then load that file into your browser.

Take a look at the third and fourth inputs. By populating the

value parameter, you display a

default value in the field, which the users can then change if they

wish. With sensible default values you can often make your web forms

more user-friendly by minimizing unnecessary typing. The result of the

previous code looks like Figure 11-3. Of course, this

was created just to illustrate default values, and because the program

calc.php has not been written, the

form will not do anything if submitted.

Default values are also used for hidden fields if you want to pass extra information from your web page to your program, in addition to what users enter. We’ll look at hidden fields later in this chapter.

Input Types

HTML forms are very versatile and allow you to submit a wide range of different types of inputs, ranging from text boxes and text areas to checkboxes, radio buttons, and more.

Text boxes

Probably the type of input you will use most often is the text box. It accepts a wide range of alphanumeric text and other characters in a single-line box. The general format of a text box input is:

<input type="text" name="name" size="size" maxlength="length" value="value" />

We’ve already covered the name and value parameters, but two more are

introduced here: size and maxlength. The size parameter specifies the width of the

box, in characters of the current font, as it should appear on the

screen, and maxlength specifies the

maximum number of characters that a user is allowed to enter into the

field.

The only required parameters are type, which tells the web browser what type

of input is to be expected, and name, for providing a name to the input that

is then used to process the field upon receipt of the submitted

form.

Text areas

When you need to accept input of more than a single line of text, use a text area. This is similar to a text box but, because it allows multiple lines, it has some different parameters. Its general format looks like this:

<textarea name="name" cols="width" rows="height" wrap="type"> </textarea>

The first thing to notice is that <textarea> has its own tag and is not

a subtype of the <input> tag.

It therefore requires a closing </textarea> to end input.

Instead of a default parameter, if you have default text to

display, you must put it before the closing </textarea>, like this:

<textarea name="name" cols="width" rows="height" wrap="type"> This is some default text. </textarea>

It will then be displayed and be editable by the user. To

control the width and height, use the cols and rows parameters. Both use the character

spacing of the current font to determine the size of the area. If you

omit these values, a default input box will be created that will vary

in dimensions depending on the browser used, so you should always

define them to be certain about how your form will appear.

Lastly, you can control how the text entered into the box will

wrap (and how any such wrapping will be sent to the server) using the

wrap parameter. Table 11-1 shows the wrap

types available. If you leave out the wrap parameter, soft wrapping is

used.

Type | Action |

| Text does not wrap and lines appear exactly as the user types them. |

| Text wraps but is sent to the server as one long string without carriage returns and line feeds. |

| Text wraps and is sent to the server in wrapped format with soft returns and line feeds. |

Checkboxes

When you want to offer a number of different options to a user, from which he can select one or more items, checkboxes are the way to go. The format to use is:

<input type="checkbox" name="name" value="value" checked="checked" />

If you include the checked

parameter, the box is already checked when the browser is displayed

(the string you assign to the parameter doesn’t matter; the parameter

just has to be present). If you don’t include the parameter, the box

is shown unchecked. Here is an example of an unchecked box:

I Agree <input type="checkbox" name="agree" />

If the user doesn’t check the box, no value will be submitted.

But if he does, a value of “on” will be submitted for the field named

agree. If you prefer to have your

own value submitted instead of the word “on” (such as the number 1),

you could use the following syntax:

I Agree <input type="checkbox" name="agree" value="1" />

On the other hand, if you wish to offer a newsletter to your readers when submitting a form, you might want to have the checkbox already checked as the default value:

Subscribe? <input type="checkbox" name="news" checked="checked" />

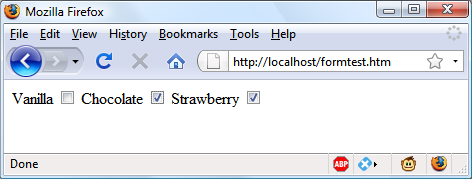

If you want to allow groups of items to be selected at one time, assign them all the same name. However, be aware that only the last item checked will be submitted, unless you pass an array as the name. For example, Example 11-4 allows the user to select her favorite ice cream flavors (see Figure 11-4 for how it displays in a browser).

Vanilla <input type="checkbox" name="ice" value="Vanilla" /> Chocolate <input type="checkbox" name="ice" value="Chocolate" /> Strawberry <input type="checkbox" name="ice" value="Strawberry" />

If only one of the checkboxes is selected, such as the second

one, only that item will be submitted (the field named ice will be assigned the value "Chocolate"). But if two or more are

selected, only the last value will be submitted, with prior values

being ignored.

If you want exclusive behavior—so that only

one item can be submitted—you should use radio

buttons (see the next section). If, however, you want to

allow multiple submissions, you have to slightly alter the HTML, as

shown in Example 11-5

(note the addition of the square brackets, [], following the values of ice):

Vanilla <input type="checkbox" name="ice[]" value="Vanilla" /> Chocolate <input type="checkbox" name="ice[]" value="Chocolate" /> Strawberry <input type="checkbox" name="ice[]" value="Strawberry" />

Now when the form is submitted, if any of these items have been

checked, an array called ice will

be submitted that contains any and all selected values. In each case,

you can extract either the single submitted value or the array of

values to a variable, like this:

$ice = $_POST['ice'];

If the field ice has been

posted as a single value, $ice will

be a single string, such as "Strawberry". But if ice was defined in the form as an array

(like in Example 11-5),

$ice will be an array, and its

number of elements will be the number of values submitted. Table 11-2 shows the seven

possible sets of values that could be submitted by this HTML for one,

two, or all three selections. In each case, an array of one, two, or

three items is created.

One value submitted | Two values submitted | Three values submitted |

|

|

|

If $ice is an array, the PHP

code to display its contents is quite simple and might look like

this:

foreach($ice as $item) echo "$item<br />";

This uses the standard PHP foreach construct to iterate through the

array $ice and pass each element’s

value into the variable $item,

which is then displayed using the echo command. The <br /> is just an HTML formatting

device, to force a new line after each flavor in the display.

By default, checkboxes are square.

Radio buttons

Radio buttons are named after the push-in preset buttons found on many older radios, where any previously depressed button pops back up when another is pressed. They are used when you want only a single value to be returned from a selection of two or more options. All the buttons in a group must use the same name and, because only a single value is returned, you do not have to pass an array.

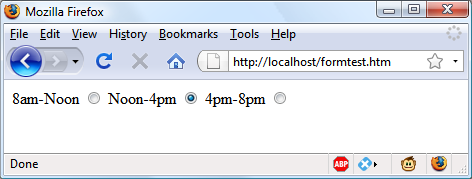

For example, if your website offers a choice of delivery times for items purchased from your store, you might use HTML like that in Example 11-6 (see Figure 11-5 to see how it displays).

8am-Noon<input type="radio" name="time" value="1" />| Noon-4pm<input type="radio" name="time" value="2" checked="checked"/>| 4pm-8pm<input type="radio" name="time" value="3" />

Here, the second option, Noon–4pm, has been selected by default.

Providing a default choice ensures that at least one delivery time

will be selected, which users can change to one of the other two

options if they prefer. Had one of the items not been already checked,

the user might forget to select an option and no value would be

submitted at all for the delivery time.

By default, radio buttons are round.

Hidden fields

Sometime it is convenient to have hidden form fields so that you can keep track of the state of form entry. For example, you might wish to know whether a form has already been submitted. You can achieve this by adding some HTML such as the following to your PHP code:

echo '<input type="hidden" name="submitted" value="yes" />'

This is a simple PHP echo

statement that adds an input field to the HTML form. Let’s assume the

form was created outside the program and displayed to the user. The

first time the PHP program receives the input, this line of code has

not run, so there will be no field named submitted. The PHP program recreates the

form, adding the input field. Then, when the visitor resubmits the

form, the PHP program receives it with the submitted field set to "yes". The code can simply check whether the

field is present:

if (isset($_POST['submitted']))

{...Hidden fields can also be useful for storing other details, such as a session ID string that you might create to identify a user, and so on.

Warning

Never treat hidden fields as secure, because they are not. The HTML containing them can easily be viewed using a browser’s view source feature.

Select

The select tag lets you

create a drop-down list of options, offering either single or multiple

selections. It conforms to the following syntax:

<select name="name" size="size" multiple="multiple">

The parameter size is the

number of lines to display. Clicking on the display causes a list to

drop down showing all the options. If you use the multiple parameter, the user can select

multiple options from the list by pressing the Ctrl key when clicking.

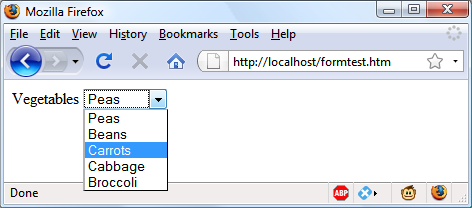

So, to ask a user for his favorite vegetable from a choice of five,

you might use HTML like that in Example 11-7, which

offers a single selection.

Vegetables <select name="veg" size="1"> <option value="Peas">Peas</option> <option value="Beans">Beans</option> <option value="Carrots">Carrots</option> <option value="Cabbage">Cabbage</option> <option value="Broccoli">Broccoli</option> </select>

This HTML offers five choices, with the first one, Peas, preselected (due to it being the first item). Figure 11-6 shows the output where the list has been clicked on to drop it down, and the option Carrots has been highlighted.

If you want to have a different default option offered first

(such as Beans), use the selected tag, like this:

<option selected="selected" value="Beans">Beans</option>

You can also allow for users to select more than one item, as in Example 11-8.

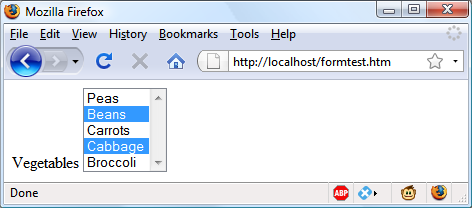

Vegetables <select name="veg" size="5" multiple="multiple"> <option value="Peas">Peas</option> <option value="Beans">Beans</option> <option value="Carrots">Carrots</option> <option value="Cabbage">Cabbage</option> <option value="Broccoli">Broccoli</option> </select>

This HTML is not very different; the only changes are that the

size has been changed to "5" and

the parameter multiple has been

added. But, as you can see from Figure 11-7, it is now

possible to select more than one option by using the Ctrl key when

clicking.

You can leave out the size

parameter if you wish, and the output will be the same, but with a

larger list the drop-down box might take up too much screen space, so

I recommend that you pick a suitable number of rows and stick with it.

I also recommend against multiple select boxes smaller than two rows

in height—some browsers may not correctly display the scroll bars

needed to access it.

You can also use the selected

tag within a multiple select and can, in fact, have more than one

option preselected if you wish.

Labels

You can provide an even better user experience by utilizing the

<label> tag. With it, you can

surround a form element, making it selectable by clicking any visible

part contained between the opening and closing <label> tags.

For example, going back to the example of choosing a delivery time, you could allow the user to click on the radio button itself and the associated text, like this:

<label>8am-Noon<input type="radio" name="time" value="1" /></label>

The text will not be underlined like a hyperlink when you do this, but as the mouse pointer passes over it it will change to an arrow instead of a text cursor, indicating that the whole item is clickable.

The submit button

To match the type of form being submitted, you can change the

text of the submit button to anything you like by using the value parameter, like this:

<input type="submit" value="Search" />

You can also replace the standard text button with a graphic image of your choice, using HTML such as this:

<input type="image" name="submit" src="image.gif" />

Sanitizing Input

Now we return to PHP programming. It can never be emphasized enough that handling user data is a security minefield, and that it is essential to learn to treat all such data with the utmost caution from the word go. It’s actually not that difficult to sanitize user input from potential hacking attempts, and it must be done.

The first thing to remember is that regardless of what constraints you have placed in an HTML form to limit the types and sizes of inputs, it is a trivial matter for a hacker to use her browser’s view source feature to extract the form and modify it to provide malicious input to your website.

Therefore, you must never trust any variable that you fetch from

either the $_GET or $_POST arrays until you have processed it. If

you don’t, users may try to inject JavaScript into the data to interfere

with your site’s operation, or even attempt to add MySQL commands to

compromise your database.

Instead of just using code such as the following when reading in user input:

$variable = $_POST['user_input'];

you should also use one or more of the following lines of code. For example, to prevent escape characters being injected into a string that will be presented to MySQL, you should use the following (remembering that this function takes into account the current character set of a MySQL connection, so it can be used only with an open connection):

$variable = mysql_real_escape_string($variable);

To get rid of unwanted slashes, such as those inserted using the

(now deprecated) magic_quotes_gpc

directive, use:

$variable = stripslashes($variable);

And to remove any HTML from a string, use the following:

$variable = htmlentities($variable);

For example, this would change a string of interpretable HTML code

like <b>hi</b> into

<b>hi</b>, which

displays as text and won’t be interpreted as HTML tags.

Finally, if you wish to strip HTML entirely from an input, use the following:

$variable = strip_tags($variable);

In fact, until you know exactly what sanitization you require for a program, Example 11-9 shows a pair of functions that bring all these checks together to provide a very good level of security.

<?php

function sanitizeString($var)

{

if (get_magic_quotes_gpc()) $var = stripslashes($var);

$var = htmlentities($var);

$var = strip_tags($var);

return $var;

}

function sanitizeMySQL($var)

{

$var = mysql_real_escape_string($var);

$var = sanitizeString($var);

return $var;

}

?>Add this code to the end of your PHP programs and you can then call it for each user input to sanitize, like this:

$variable = sanitizeString($_POST['user_input']);

Or, when you have an open MySQL connection:

$variable = sanitizeMySQL($_POST['user_input']);