Using Sessions

Because your program can’t tell what variables were set in other programs—or even what values the program itself set the previous time it ran—you’ll sometimes want to track what your users are doing from one web page to another. You can do this by setting hidden fields in a form, as seen in Chapter 10, and checking the value of the fields after the form is submitted. However, PHP provides a much more powerful and simpler solution, in the form of sessions. These are groups of variables that are stored on the server but relate only to the current user. To ensure that the right variables are applied to the right users, a cookie is saved in the users’ web browsers to uniquely identify them.

This cookie has meaning only to the web server and cannot be used to

ascertain any information about a user. You might ask about those users

who have their cookies turned off. Well, that’s not a problem since PHP

4.2.0, because it will identify when this is the case and place a cookie

token in the GET portion of each URL

request instead. Either way, sessions provide a solid way of keeping track

of your users.

Starting a Session

Starting a session requires calling the PHP function session_start before any HTML has been output,

similarly to how cookies are sent during header exchanges. Then, to

begin saving session variables, you just assign them as part of the

$_SESSION array, like this:

$_SESSION['variable'] = $value;

They can then be read back just as easily in later program runs, like this:

$variable = $_SESSION['variable'];

Now assume that you have an application that always needs access

to the username, password, forename, and surname of each user, as stored

in the table users, which you should

have created a little earlier. Let’s further modify authenticate.php from Example 12-4 to set up a session once a

user has been authenticated.

Example 12-5 shows

the changes needed. The only difference is the contents of the if ($token == $row[3]) section, which now

starts by opening a session and saving these four variables into it.

Type this program in (or modify Example 12-4) and save it as authenticate2.php. But don’t run it in your

browser yet, as you will also need to create a second program in a

moment.

<?php //authenticate2.php

require_once 'login.php';

$db_server = mysql_connect($db_hostname, $db_username, $db_password);

if (!$db_server) die("Unable to connect to MySQL: " . mysql_error());

mysql_select_db($db_database)

or die("Unable to select database: " . mysql_error());

if (isset($_SERVER['PHP_AUTH_USER']) &&

isset($_SERVER['PHP_AUTH_PW']))

{

$un_temp = mysql_entities_fix_string($_SERVER['PHP_AUTH_USER']);

$pw_temp = mysql_entities_fix_string($_SERVER['PHP_AUTH_PW']);

$query = "SELECT * FROM users WHERE username='$un_temp'";

$result = mysql_query($query);

if (!$result) die("Database access failed: " . mysql_error());

elseif (mysql_num_rows($result))

{

$row = mysql_fetch_row($result);

$salt1 = "qm&h*";

$salt2 = "pg!@";

$token = md5("$salt1$pw_temp$salt2");

if ($token == $row[3])

{

session_start();

$_SESSION['username'] = $un_temp;

$_SESSION['password'] = $pw_temp;

$_SESSION['forename'] = $row[0];

$_SESSION['surname'] = $row[1];

echo "$row[0] $row[1] : Hi $row[0],

you are now logged in as '$row[2]'";

die ("<p><a href=continue.php>Click here to continue</a></p>");

}

else die("Invalid username/password combination");

}

else die("Invalid username/password combination");

}

else

{

header('WWW-Authenticate: Basic realm="Restricted Section"');

header('HTTP/1.0 401 Unauthorized');

die ("Please enter your username and password");

}

function mysql_entities_fix_string($string)

{

return htmlentities(mysql_fix_string($string));

}

function mysql_fix_string($string)

{

if (get_magic_quotes_gpc()) $string = stripslashes($string);

return mysql_real_escape_string($string);

}

?>One other addition to the program is the “Click here to continue” link with a destination URL of continue.php. This will be used to illustrate how the session will transfer to another program or PHP web page. So, create continue.php by typing in the program in Example 12-6 and saving it.

<?php // continue.php

session_start();

if (isset($_SESSION['username']))

{

$username = $_SESSION['username'];

$password = $_SESSION['password'];

$forename = $_SESSION['forename'];

$surname = $_SESSION['surname'];

echo "Welcome back $forename.<br />

Your full name is $forename $surname.<br />

Your username is '$username'

and your password is '$password'.";

}

else echo "Please <a href=authenticate2.php>click here</a> to log in.";

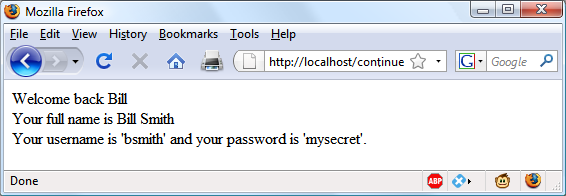

?>Now you are ready to call up authenticate2.php into your browser, enter a username of “bsmith” and password of “mysecret” (or “pjones” and “acrobat”) when prompted, and click on the link to load in continue.php. When your browser calls it up, the result should be something like Figure 12-5.

Sessions neatly confine to a single program the extensive code

required to authenticate and log in a user. Once a user has been

authenticated and you have created a session, your program code becomes

very simple indeed. You need only call up session_start and look up any variables to

which you need access from $_SESSION.

In Example 12-6, a quick test

of whether $_SESSION['username'] has

a value is enough to let you know that the current user is

authenticated, because session variables are stored on the server

(unlike cookies, which are stored on the web browser) and can therefore

be trusted.

If $_SESSION['username'] has

not been assigned a value, no session is active, so the last line of

code in Example 12-6 directs users to

the login page at authenticate2.php.

Note

The continue.php program prints back the value of the user’s password to show you how session variables work. In practice, you already know that the user is logged in, so it should not be necessary to keep track of (or display) any passwords, and doing so would be a security risk.

Ending a Session

When the time comes to end a session—usually when a user requests

to log out from your site—you can use the session_destroy function, as in Example 12-7. This example

provides a useful function for totally destroying a session, logging out

a user, and unsetting all session variables.

<?php

function destroy_session_and_data()

{

session_start();

$_SESSION = array();

if (session_id() != "" || isset($_COOKIE[session_name()]))

setcookie(session_name(), '', time() - 2592000, '/');

session_destroy();

}

?>To see this in action, you could modify continue.php as in Example 12-8.

<?php

session_start();

if (isset($_SESSION['username']))

{

$username = $_SESSION['username'];

$password = $_SESSION['password'];

$forename = $_SESSION['forename'];

$surname = $_SESSION['surname'];

destroy_session_and_data();

echo "Welcome back $forename.<br />

Your full name is $forename $surname.<br />

Your username is '$username'

and your password is '$password'.";

}

else echo "Please <a href=authenticate2.php>click here</a> to log in.";

function destroy_session_and_data()

{

$_SESSION = array();

if (session_id() != "" || isset($_COOKIE[session_name()]))

setcookie(session_name(), '', time() - 2592000, '/');

session_destroy();

}

?>The first time you surf from authenticate2.php to continue.php, it will display all the session

variables. But, because of the call to destroy_session_and_data, if you then click on

your browser’s Reload button the session will have been destroyed and

you’ll be prompted to return to the login page.

Setting a timeout

There are other times when you might wish to close a user’s session yourself, such as when the user has forgotten or neglected to log out and you wish the program to do it on her behalf for her own security. The way to do this is to set the timeout after which a logout will automatically occur if there has been no activity.

To do this, use the ini_set

function as follows. This example sets the timeout to exactly one

day:

ini_set('session.gc_maxlifetime', 60 * 60 * 24);If you wish to know what the current timeout period is, you can display it using the following:

echo ini_get('session.gc_maxlifetime');Session Security

Although I mentioned that once you had authenticated a user and

set up a session you could safely assume that the session variables were

trustworthy, this isn’t exactly the case. The reason is that it’s

possible to use packet sniffing (sampling of data)

to discover session IDs passing across a network. Additionally, if the

session ID is passed in the GET part

of a URL, it might appear in external site server logs. The only truly

secure way of preventing these from being discovered is to implement a

Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) and run HTTPS instead of HTTP web pages.

That’s beyond the scope of this book, although you may like to take a

look at http://apache-ssl.org for details on

setting up a secure web server.

Preventing session hijacking

When SSL is not a possibility, you can further authenticate users by storing their IP address along with their other details. Do this by adding a line such as the following when you store a user’s session:

$_SESSION['ip'] = $_SERVER['REMOTE_ADDR'];

Then, as an extra check, whenever any page loads and a session

is available, perform the following check. It calls the function

different_user if the stored IP

address doesn’t match the current one:

if ($_SESSION['ip'] != $_SERVER['REMOTE_ADDR']) different_user();

What code you place in your different_user function is up to you. I

recommend that you simply delete the current session and ask the user

to log in again due to a technical error. Don’t say any more than

that, or you’re giving away information that is potentially

useful.

Of course, you need to be aware that users on the same proxy server, or sharing the same IP address on a home or business network, will have the same IP address. Again, if this is a problem for you, use SSL. You can also store a copy of the browser’s user agent string (a string that developers put in their browsers to identify them by type and version), which, due to the wide variety of browser types, versions, and computer platforms, might help to distinguish users. Use the following to store the user agent:

$_SESSION['ua'] = $_SERVER['HTTP_USER_AGENT'];

And use this to compare the current agent string with the saved one:

if ($_SESSION['ua'] != $_SERVER['HTTP_USER_AGENT']) different_user();

Or, better still, combine the two checks like this and save the

combination as an md5 hexadecimal

string:

$_SESSION['check'] = md5($_SERVER['REMOTE_ADDR'] .

$_SERVER['HTTP_USER_AGENT']);Then use this to compare the current and stored strings:

if ($_SESSION['check'] != md5($_SERVER['REMOTE_ADDR'] .

$_SERVER['HTTP_USER_AGENT'])) different_user();Preventing session fixation

Session fixation happens when a malicious

user tries to present a session ID to the server rather than letting

the server create one. It can happen when a user takes advantage of

the ability to pass a session ID in the GET part of a URL, like this:

http://yourserver.com/authenticate.php?PHPSESSID=123456789

In this example, the made-up session ID of 123456789 is being passed to the server. Now consider Example 12-9, which is susceptible to session fixation. To see how, type it in and save it as sessiontest.php.

<?php // sessiontest.php session_start(); if (!isset($_SESSION['count'])) $_SESSION['count'] = 0; else ++$_SESSION['count']; echo $_SESSION['count']; ?>

Once saved, call it up in your browser using the following URL (prefacing it with the correct pathname, such as http://localhost/web/):

sessiontest.php?PHPSESSID=1234

Press Reload a few times and you’ll see the counter increase. Now try browsing to:

sessiontest.php?PHPSESSID=5678

Press Reload a few times here and you should see it count up again from zero. Leave the counter on a different number than the first URL and then go back to the first URL and see how the number changes back. You have created two different sessions of your own choosing here, and you could easily create as many as you needed.

The reason this approach is so dangerous is that a malicious attacker could try to distribute these types of URLs to unsuspecting users, and if any of them followed these links, the attacker would be able to come back and take over any sessions that had not been deleted or expired!

To prevent this, you can use the function session_regenerate_id to change the session

ID. This function keeps all current session variable values, but

replaces the session ID with a new one that an attacker cannot

know.

Now, when you receive a request, you can check for a special session variable that you arbitrarily invent. If it doesn’t exist, you know that this is a new session, so you simply change the session ID and set the special session variable to note the change.

Example 12-10 shows what code to do

this might look like using the session variable initiated.

<?php

session_start();

if (!isset($_SESSION['initiated']))

{

session_regenerate_id();

$_SESSION['initiated'] = 1;

}

if (!isset($_SESSION['count'])) $_SESSION['count'] = 0;

else ++$_SESSION['count'];

echo $_SESSION['count'];

?>This way, an attacker can come back to your site using any of the session IDs that he generated, but none of them will call up another user’s session, as they will all have been replaced with regenerated IDs. If you want to be ultra-paranoid, you can even regenerate the session ID on each request.

Forcing cookie-only sessions

If you are prepared to require your users to enable cookies on

your website, you can use the ini_set function like this:

ini_set('session.use_only_cookies', 1);With that setting, the ?PHPSESSID= trick will be completely

ignored. If you use this security measure, I also recommend you inform

your users that your site requires cookies, so they know what’s wrong

if they don’t get the results they want.

Using a shared server

On a server shared with other accounts, you will not want to

have all your session data saved into the same directory as theirs.

Instead, you should choose a directory to which only your account has

access (and that is not web-visible) to store your sessions, by

placing an ini_set call near the

start of your program, like this:

ini_set('session.save_path', '/home/user/myaccount/sessions');The configuration option will keep this new value only during the program’s execution, and the original configuration will be restored at the program’s ending.

This sessions folder can fill up quickly; you may wish to periodically clear out older sessions according to how busy your server gets. The more it’s used, the less time you will want to keep a session stored.

Note

Remember that your websites can and will be subject to hacking attempts. There are automated bots running riot around the Internet trying to find sites vulnerable to exploits. So, whatever you do, whenever you are handling data that is not 100 percent generated within your own program, you should always treat it with the utmost caution.

You should now have a very good grasp of both PHP and MySQL, so in the next chapter it’s time to introduce the third major technology covered by this book, JavaScript.