The Document Object Model (DOM)

The designers of JavaScript were very smart. Rather than just creating yet another scripting language (which would still have been a pretty good improvement at the time), they had the vision to build it around the Document Object Model, or DOM. This breaks down the parts of an HTML document into discrete objects, each with its own properties and methods and each subject to JavaScript’s control.

JavaScript separates objects, properties, and methods using a period

(one good reason why + is the string

concatenation operator in JavaScript, rather than the period). For

example, let’s consider a business card as an object we’ll call card. This object contains properties such as a

name, address, phone number, and so on. In the syntax of JavaScript, these

properties would look like this:

card.name card.phone card.address

Its methods are functions that retrieve, change, and otherwise act

on the properties. For instance, to invoke a method that displays the

properties of object card, you might

use syntax such as:

card.display()

Have a look at some of the earlier examples in this chapter, where

the statement document.write is used.

Now that you understand how JavaScript is based around objects, you will

see that write is actually a method of

the document object.

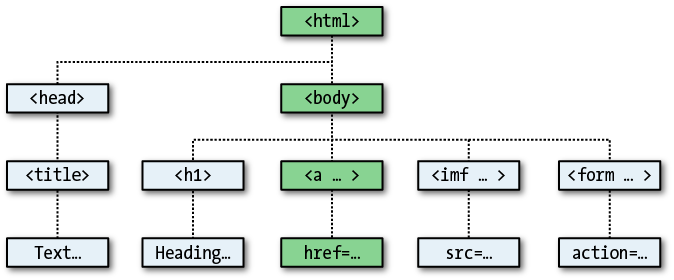

Within JavaScript, there is a hierarchy of parent and child objects. This is what is known as the Document Object Model (see Figure 13-3).

The figure uses HTML tags that you are already familiar with to illustrate the parent/child relationship between the various objects in a document. For example, a URL within a link is part of the body of an HTML document. In JavaScript, it is referenced like this:

url = document.links.linkname.href

Notice how this follows the central column down. The first part,

document, refers to the <html> and <body> tags, links.linkname to the <a ...> tag, and href to the href=... element.

Let’s turn this into some HTML and a script to read a link’s properties. Type in Example 13-8 and save it as linktest.html, then call it up in your browser.

Note

If you are using Microsoft Internet Explorer as your main

development browser, please just read through this section, then read

the upcoming section entitled “But It’s Not That Simple,” and then come

back and try the example with the getElementById modification discussed there.

Without it, this example will not work for you.

<html>

<head>

<title>Link Test</title>

</head>

<body>

<a id="mylink" href="http://mysite.com">Click me</a><br />

<script>

url = document.links.mylink.href

document.write('The URL is ' + url)

</script>

</body>

</html>Note the short form of the <script> tags, where I have omitted the

parameter type="text/JavaScript" to

save you some typing. If you wish, just for the purposes of testing this

(and other examples), you could also omit everything outside of the

<script> and </script> tags. The output from this

example is:

Click me

The URL is http://mysite.comThe second line of output comes from the document.write method. Notice how the code

follows the document tree down from document to links to mylink (the id given to the link) to href (the URL destination value).

There is also a short form that works equally well, which starts

with the value in the id attribute:

mylink.href. So, you can replace

this:

url = document.links.mylink.href

with the following:

url = mylink.href

But It’s Not That Simple

If you tried Example 13-8 in Safari, Firefox, Opera, or Chrome, it will have worked just great. But in Internet Explorer it will fail, because Microsoft’s implementation of JavaScript, called JScript, has many subtle differences from the recognized standards. Welcome to the world of advanced web development!

So, what can we do about this? Well, in this case, instead of

using the links child object of the

parent document object, which

Internet Explorer balks at when used this way, you have to replace it

with a method to fetch the element by its id. Therefore, the following line:

url = document.links.mylink.href

can be replaced with this one:

url = document.getElementById('mylink').hrefAnd now the script will work in all major browsers. Incidentally,

when you don’t have to look up the element by id, the short form that follows will still

work in Internet Explorer, as well as the other browsers:

url = mylink.href

Another use for the $

As mentioned earlier, the $

symbol is allowed in JavaScript variable and function names. Because

of this, you may sometimes encounter some strange-looking code, like

this:

url = $('mylink').hrefSome enterprising programmers have decided that the getElementById function is so prevalent in

JavaScript that they have written a function to replace it called

$, shown in Example 13-9.

<script>

function $(id)

{

return document.getElementById(id)

}

</script>Therefore, as long as you have included the $ function in your code, syntax such

as:

$('mylink').hrefcan replace code such as:

document.getElementById('mylink').hrefUsing the DOM

The links object is actually an

array of URLs, so the mylink URL in

Example 13-8 can also be safely

referred to on all browsers in the following way (because it’s the

first, and only, link):

url = document.links[0].href

If you want to know how many links there are in an entire

document, you can query the length

property of the links object like

this:

numlinks = document.links.length

You can therefore extract and display all links in a document like this:

for (j=0 ; j < document.links.length ; ++j)

document.write(document.links[j].href + '<br />')The length of something is a

property of every array, and many objects as well. For example, the

number of items in your browser’s web history can be queried like

this:

document.write(history.length)

However, to stop websites from snooping on your browsing history,

the history object stores only the

number of sites in the array: you cannot read from or write to these

values. But you can replace the current page with one from the history,

if you know what position it has within the history. This can be very

useful in cases in which you know that certain pages in the history came

from your site, or you simply wish to send the browser back one or more

pages, which is done with the go

method of the history object. For

example, to send the browser back three pages, issue the following

command:

history.go(-3)

You can also use the following methods to move back or forward a page at a time:

history.back() history.forward()

In a similar manner, you can replace the currently loaded URL with one of your choosing, like this:

document.location.href = 'http://google.com'

Of course, there’s a whole lot more to the DOM than reading and modifying links. As you progress through the following chapters on JavaScript, you’ll become quite familiar with the DOM and how to access it.