Sending XML Requests

Although the objects we’ve been creating are called XMLHttpRequest objects, so far we have made

absolutely no use of XML. This is where the term “Ajax” is a bit of a

misnomer, because the technology actually allows you to request any type

of textual data, with XML being just one option. As you have seen, we have

requested an entire HTML document via Ajax, but we could equally have

asked for a text page, a string or number, or even spreadsheet

data.

So, let’s modify the previous example document and PHP program to fetch some XML data. To do this, take a look at the PHP program first: xmlget.php, shown in Example 17-6.

<?php

if (isset($_GET['url'])) {

header('Content-Type: text/xml');

echo file_get_contents("http://".sanitizeString($_GET['url']));

}

function sanitizeString($var) {

$var = strip_tags($var);

$var = htmlentities($var);

return stripslashes($var);

}

?>This program has been very slightly modified (the changes are shown in bold) to first output the correct XML header before returning a fetched document. No checking is done here, as it is assumed the calling Ajax will request an actual XML document.

Now on to the HTML document, xmlget.html, shown in Example 17-7.

<html><head><title>Ajax XML Example</title> </head><body> <h2>Loading XML content into a DIV</h2> <div id='info'>This sentence will be replaced</div> <script> nocache = "&nocache=" + Math.random() * 1000000 url = "rss.news.yahoo.com/rss/topstories" request = new ajaxRequest() request.open("GET", "xmlget.php?url=" + url + nocache, true) out = ""; request.onreadystatechange = function() { if (this.readyState == 4) { if (this.status == 200) { if (this.responseXML != null) { titles = this.responseXML.getElementsByTagName('title') for (j = 0 ; j < titles.length ; ++j) { out += titles[j].childNodes[0].nodeValue + '<br />' } document.getElementById('info').innerHTML = out } else alert("Ajax error: No data received") } else alert( "Ajax error: " + this.statusText) } } request.send(null) function ajaxRequest() { try { var request = new XMLHttpRequest() } catch(e1) { try { request = new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP") } catch(e2) { try { request = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP") } catch(e3) { request = false } } } return request } </script></body></html>

Again, the differences have been highlighted in bold, so you can see that this code is substantially similar to previous versions. The first difference is that the URL now being requested, rss.news.yahoo.com/rss/topstories, contains an XML document, the Yahoo! News Top Stories feed.

The other big change is the use of the responseXML property, which replaces the

responseText property. Whenever a

server returns XML data, responseText

will return a null value, and responseXML will contain the XML returned

instead.

However, responseXML doesn’t

simply contain a string of XML text: it is actually a complete XML

document object that can be examined and parsed using DOM tree methods and

properties. This means it is accessible, for example, by the JavaScript

getElementsByTagName method.

About XML

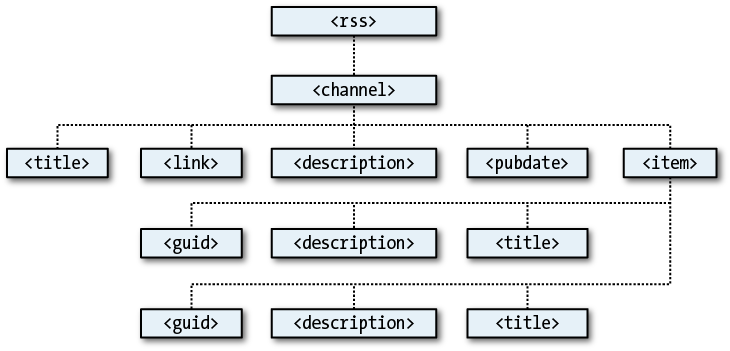

An XML document will generally take the form of the RSS feed shown in Example 17-8. However, the beauty of XML is that this type of structure can be stored internally in a DOM tree (see Figure 17-3) to make it quickly searchable.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<rss version="2.0">

<channel>

<title>RSS Feed</title>

<link>http://website.com</link>

<description>website.com's RSS Feed</description>

<pubDate>Mon, 16 May 2011 00:00:00 GMT</pubDate>

<item>

<title>Headline</title>

<guid>http://website.com/headline</guid>

<description>This is a headline</description>

</item>

<item>

<title>Headline 2</title>

<guid>http://website.com/headline2</guid>

<description>The 2nd headline</description>

</item>

</channel>

</rss>Therefore, using the getElementsByTagName method, you can quickly

extract the values associated with various tags without a lot of string

searching. This is exactly what we do in Example 17-7,

where the following command is issued:

titles = this.responseXML.getElementsByTagName('title')This single command has the effect of placing all the values of

the “title” elements into the array titles. From there, it is a simple matter to

extract them with the following expression (where j is the title to access):

titles[j].childNodes[0].nodeValue

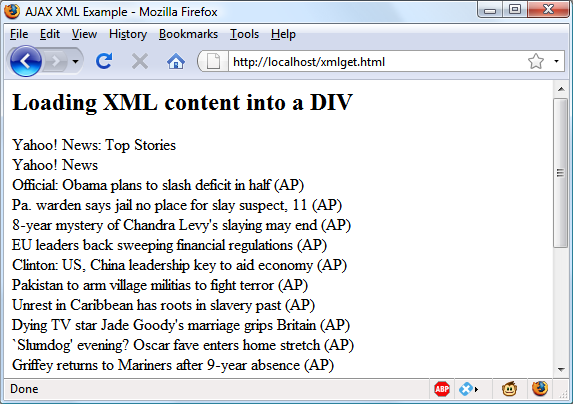

All the titles are then appended to the string variable out and, once all have been processed, the

result is inserted into the empty <div> at the document start. When you

call up xmlget.html in your

browser, the result will be something like Figure 17-4.

Note

As with all form data, you can use either the POST or the GET method when requesting XML data—your

choice will make little difference to the result.

Why Use XML?

You may ask why you would use XML other than for fetching XML documents such as RSS feeds. Well, the simple answer is that you don’t have to, but if you wish to pass structured data back to your Ajax applications, it could be a real pain to send a simple, unorganized jumble of text that would need complicated processing in JavaScript.

Instead, you can create an XML document and pass that back to the Ajax function, which will automatically place it into a DOM tree as easily accessible as the HTML DOM object with which you are now familiar.