Using Interrupts

JavaScript provides access to interrupts, a method by which you can ask the browser to call your code after a set period of time, or even to keep calling it at specified intervals. This gives you a means of handling background tasks such as Ajax communications, or even things like animating web elements.

There are two types of interrupt, setTimeout and setInterval, which have accompanying clearTimeout and clearInterval functions for turning them off

again.

Using setTimeout

When you call setTimeout, you

pass it some JavaScript code or the name of a function, and a value in

milliseconds representing how long to wait before the code should be

executed, like this:

setTimeout(dothis, 5000)

Your dothis function might look

like this:

function dothis()

{

alert('This is your wakeup alert!');

}Note

In case you are wondering, you cannot simply specify alert() (with parens) as a function to be

called by setTimeout, because the

function would be executed immediately. Only when you provide a

function name without argument parentheses (for example, alert) can you safely pass the function

name, so that its code will be executed only when the timeout

occurs.

Passing a string

When you need to provide an argument to a function, you can also

pass a string value to the setTimeout function, which will not be

executed until the correct time. For example:

setTimeout("alert('Hello!')", 5000)In fact, you can provide as many lines of JavaScript code as you like, if you place a semicolon after each statement:

setTimeout("document.write('Starting'); alert('Hello!')", 5000)Repeating timeouts

One technique some programmers use to provide repeating

interrupts with setTimeout is to

call the setTimeout function from

the code called by it, as in the following example, which will

initiate a never-ending loop of alert windows:

setTimeout(dothis, 5000)

function dothis()

{

setTimeout(dothis, 5000)

alert('I am annoying!')

}Now the alert will pop up every five seconds.

Canceling a Timeout

Once a timeout has been set up, you can cancel it if you

previously saved the value returned from the initial call to setTimeout, like this:

handle = setTimeout(dothis, 5000)

Armed with the value in handle,

you can now cancel the interrupt at any point up until its due time,

like this:

clearTimeout(handle)

When you do this, the interrupt is completely forgotten, and the code assigned to it will not get executed.

Using setInterval

An easier way to set up regular interrupts is to use the setInterval function. It works in just the

same way, except that having popped up after the interval you specify in

milliseconds, it will do so again after that interval again passes, and

so on forever, unless you cancel it.

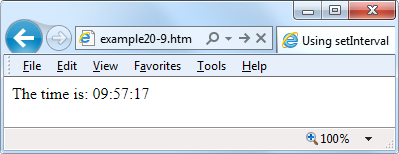

Example 20-9 uses this function to display a simple clock in the browser, as shown in Figure 20-4.

<html>

<head>

<title>Using setInterval</title>

<script src='OSC.js'></script>

</head>

<body>

The time is: <span id='time'>00:00:00</span><br />

<script>

setInterval("showtime(O('time'))", 1000)

function showtime(object)

{

var date = new Date()

object.innerHTML = date.toTimeString().substr(0,8)

}

</script>

</body>

</html>Every time ShowTime is called,

it sets the object date to the

current date and time with a call to Date:

var date = new Date()

Then the innerHTML property of

the object passed to showtime

(namely, object) is set to the

current time in hours, minutes, and seconds, as determined by a call to

toTimeString. This returns a string

such as “09:57:17 UTC+0530”, which is then truncated to just the first

eight characters with a call to the substr function:

object.innerHTML = date.toTimeString().substr(0,8)

Using the function

To use this function, you first have to create an object whose

innerHTML property will be used for

displaying the time, like this HTML:

The time is: <span id='time'>00:00:00</span>

Then, from a <script>

section of code, a call is placed to the setInterval function, like this:

setInterval("showtime(O('time'))", 1000)This call passes a string to setInterval containing the following

statement, which is set to execute once a second (every 1,000

milliseconds):

showtime(O('time'))In the rare situation where somebody disables JavaScript in her browser (which people sometimes do for security reasons), your JavaScript will not run and the user will see the original 00:00:00.

Canceling an interval

To stop a repeating interval, when you first set up the interval

with a call to setInterval, you must ensure you

make a note of the interval’s handle, like this:

handle = setInterval("showtime(O('time'))", 1000)Now you can stop the clock at any time by issuing the following call:

clearInterval(handle)

You can even set up a timer to stop the clock after a certain amount of time, like this:

setTimeout("clearInterval(handle)", 10000)This statement will issue an interrupt in 10 seconds (10,000 milliseconds) that will clear the repeating intervals.

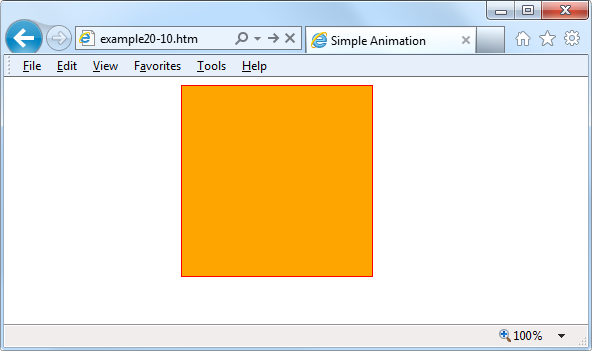

Using Interrupts for Animation

By combining a few CSS properties with a repeating interrupt, you can produce all manner of animations and effects.

For example, the code in Example 20-10

moves a square shape across the top of the browser window, all the time

ballooning up in size, as shown in Figure 20-5. Then, when

LEFT is reset to 0, the animation starts all over again.

<html>

<head>

<title>Simple Animation</title>

<script src='OSC.js'></script>

<style>

#box {

position :absolute;

background:orange;

border :1px solid red; }

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div id='box'></div>

<script>

SIZE = LEFT = 0

setInterval(animate, 30)

function animate()

{

SIZE += 10

LEFT += 3

if (SIZE == 200) SIZE = 0

if (LEFT == 600) LEFT = 0

S('box').width = SIZE + 'px'

S('box').height = SIZE + 'px'

S('box').left = LEFT + 'px'

}

</script>

</body>

</html>In the <head> of the

document, the box object is set to a

background color of 'orange' with a border value of '1px

solid red', and its position property is set to absolute so that it is allowed to be moved

around in the browser window.

Then, in the animate function,

the global variables SIZE and

LEFT are continuously updated and

then applied to the width, height, and left style attributes of the box object (adding 'px' after each to specify that the values are

in pixels), thus animating it at a frequency of once every 30

milliseconds. This gives a rate of 33.33 frames per second (1000 / 30

milliseconds).

This completes your introduction to all the topics covered in this book, and you are well on the way to becoming a seasoned web developer. But before I finish, in the final chapter I want to bring everything I’ve introduced together into a single project, so that you can see in practice how all the technologies integrate with each other.