In his 2006 book The Long Tail,[154] Chris Anderson describes the shift from the traditional retail economics of “hits,” created by limited and expensive shelf space, to the digital economics of niches that emerge when retailers can stock virtually everything. In these digital marketplaces, according to Anderson, “the number of available niche products outnumber [and collectively outsell] the hits by orders of magnitude. Those millions of niches are the Long Tail, which had been largely neglected until recently in favor of the Short Head of hits.”[155]

The same long tail principles in consumer markets apply to citizen interests in public policy.

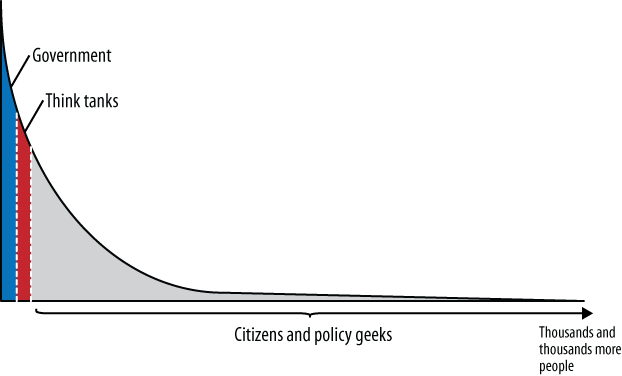

It is a long-held and false assumption that citizens don’t care about public policy. The belief is understandable: many people truly don’t care about the majority of public policy issues. There are a few geeks, such as myself, who care passionately about public policy in general, just like there are some people who are baseball geeks, or model train geeks, or nature geeks. But we shouldn’t restrict ourselves to thinking that a community must be composed only of the hardest-core geeks. While there are hardcore baseball fans who follow every player in the league, there are still a significant number of people who follow only a favorite team. Similarly, there are many people who do care about some public policy issues or even just one policy issue. They’ve always been there: some are active in politics; others volunteer; many are dedicated to a nonprofit organization. Most simply keep up with the latest developments on their pet issue—present, perhaps, but silent unless the immediate benefits become more apparent, or the transaction costs of participating are lowered. They form part of the long tail of expertise and capacity for developing and delivering public policy that has been obscured by our obsession for large professional institutions (see Figure 12-1).

I first encountered the long tail of public policy in 2001 while volunteering with a nonprofit called Canada25. Canada25’s mission was to engage young Canadians aged 20–35 in public policy debates. From 2001 through 2006 the group grew from a humble 30 members to more than 2,000 people living across the country and around the world. These members met on a regular basis, talked policy, and every 18 months held conferences on a major policy area (such as foreign policy). The ideas from these conferences were then filtered—in a process similar to open source software development—into a publication which frequently caught the attention of the press, elected officials, and public servants.

Did Canada25 get Canadians aged 20–35 interested in public policy? I don’t know. At a minimum, however, it did harness an untapped and dispersed desire by many young Canadians to participate in, and try to shape, the country’s public policy debates. While most people assume interest—and expertise—in public policy resides exclusively within civil service[156] and possibly some universities and think tanks, we discovered a long tail of interest and expertise which, thanks to collapsing transaction costs, was able to organize.

The Coasean collapse has made accessing and self-organizing within the long tail of public policy possible. While essential to moving government to a platform model, it poses enormous cultural challenges. Governments are built on the assumption that they know more, and have greater expertise, than the public. Public servants are also oriented toward managing and controlling scarce resources, not to overseeing and engaging an abundant but scattered community. Most of all, governments’ culture still values presenting a final product, not works in progress. In short, opening up the long tail of public policy requires a government that is willing to shift from a “release” it uses internally, to the “patch culture” a growing number of citizens are becoming accustomed to.