SUPPOSE YOU’RE A Platonist: you think that properties (features, attributes, whatever you like to call them) are universals and thus can be shared, can be had (exemplified, whatever) by more than one substance.2 Suppose further that you’re a Constituent Ontologist: you think that properties enter into the being of the substances that have them; that the properties of a substance somehow constitute it by being non-mereological parts of it; that by saying what properties a substance has, you thereby say what the substance is (at least in part).3 These two commitments are generally thought to give rise to a certain problem: the problem of individuation (for short, The Problem). The Problem is to give an account of what makes a substance the substance that it is. That is, The Problem is to give an account of what makes a substance one and to give an account of what distinguishes substances from one another.

As it happens, J. P. Moreland has been one of the central players in the dispute about The Problem. Here is how he sets it out. Consider the following three claims:

Bundle Theory: The only constituents of objects are their properties.

Platonism: Properties are universals and therefore are numerically identical in their instances.

The Principle of Constituent Identity (PCI): If substance a and substance b have all the same constituents, then a is numerically identical to b (that is, a just is b).

Bundle Theory, Platonism, and PCI together entail the following:

The Identity of Indiscernibles (IOI): If substance a and substance b have all the same properties, then a is numerically identical to b (that is, a just is b).4

The implication isn’t hard to see.5 Given Platonism, if a and b are both red, say, then the one universal RED is instantiated by both a and b. a and b thus share a constituent, namely the universal RED. Suppose, further, that a and b share all their properties (the “if” half—that is, the “antecedent”—of IOI). Then, by similar reasoning, Platonism entails that a and b share many constituents, namely the universals that are the properties they instantiate. By Bundle Theory, it follows that these universals are a’s and b’s only constituents. So by PCI, a is numerically identical to b; that is, a just is b. And this conclusion is the “then” half—that is, the “consequent”—of IOI. So, given Platonism, Bundle Theory, and PCI, if a and b share all their properties, then a is numerically identical to b. Which is to say, if Platonism, Bundle Theory, and PCI are true, then so is IOI. The former three entail the latter.

So far so good. We can now give an account of what makes a substance the substance that it is. In particular, IOI suggests that a substance’s properties individuate it. What makes a substance the substance that it is, what distinguishes any given substance from all the others, is that substance’s properties. Numerical difference and qualitative difference go hand in hand. You can’t have one without the other, and when you have one, you get the other too.

Trouble is—and we’re now up against a way in which The Problem is a problem—IOI is very likely false.6

There are good reasons to think that distinct but qualitatively indiscernible substances are possible.7 As a start, we can at least imagine a scenario in which there are two indiscernible substances. We might, for example, imagine a scenario in which there are two homogenous iron globes which are equivalent in size and shape, whose parts can be put in one-to-one correspondence, and so on. We can further stipulate that the only physical objects that exist are these globes, their parts, and, if there be such things, objects composed of the globes and their parts. We can at least coherently imagine such a scenario. And our ability to imagine a scenario is evidence that the scenario is indeed possible: absent a reason to think otherwise, we ought to believe that this scenario is possible, that the world could have turned out this way, because we can imagine it having turned out this way. Put another way, our ability to coherently imagine this scenario is evidence that God might’ve made just this kind of world. If He had done, there would’ve been two qualitatively indiscernible objects. IOI therefore is false.8

We should dispatch with two strategies for resisting this argument. Both attempt to allow for possibilities like the one just sketched without conceding that they make trouble for IOI. Both do this by insisting that there are, contrary to initial appearances, qualitative differences between, for example, our two iron globes. To get clear on the proposals, we’ll see how they work on our homogeneous globe possibility. It will help if we give the two globes names: “Globea” and “Globeb.”

First strategy: insist that a certain kind of relational property individuates Globea and Globeb. For example, suppose Globea and Globeb are separated by one kilometer. Then Globea has the property of being one kilometer from Globeb, a property Globeb does not have; and Globeb has the property of being one kilometer from Globea, a property Globea does not have. Therefore, Globea and Globeb do not have all the same qualitative properties and are therefore not qualitatively indiscernible.

This first strategy faces at least two problems. First, these types of relational properties seem to be possessed in virtue of the relations they correspond to. Take the property of being one kilometer from Globeb. Grant for now that Globea has this property. Even given that claim, it would seem that Globea has this property because it stands in the one kilometer from relation to Globeb. If this is true, though, Globea and Globeb must stand in the one kilometer from relation metaphysically (not temporally!) prior to Globea’s having the property of being one kilometer from Globeb.

So what? Given the metaphysical priority claim, Globea and Globeb must exist metaphysically prior to Globea having the property of being one kilometer from Globeb. The reason is that token relation instances, like the token of the one kilometer from relation that holds between Globea and Globeb, presuppose their relata. Things cannot stand in relations, and thus token relation instances cannot exist, unless the relata thereby related already do.9 But if Globea exists metaphysically prior to standing in the one kilometer from relation to Globeb, and therefore exists metaphysically prior to having the property of being one kilometer from Globeb, then the latter cannot individuate Globea. Globea must be individuated in order to exist at all, and thus Globea must be individuated metaphysically prior to having the property of being one kilometer from Globeb.

The second problem with the first strategy stems from the fact that the types of relational properties in view here are contingent features of the objects that have them. This is a problem because what individuates a thing ought to be something that explains, at least in part, what it is to be that very thing. From this it follows that what individuates a substance must individuate that substance. For if we are to explain what it is to be this very object, the explanation cannot change from time to time or from possibility to possibility. To say otherwise produces absurdity. Consider, for example, the result of saying that two otherwise identical twins are individuated by their respective spatial relationships to a certain tree. Now imagine that the twins switch places. The feature that individuated the first twin now individuates the second, and vice versa. We have thereby severed the connection between individuation and identity, and thus guarantee that our account of individuation cannot (in part) explain what it is to be one twin rather than the other.10 Given that the relational properties deployed by this first strategy are merely contingently possessed by substances, such relational properties cannot do individuative work.

So much for the first strategy.

Second strategy: go in for “haecceities,” that is, primitive qualitative properties of being a such-and-such object. The idea here is that, for each (possible) object, there is a property of being just that object, a property that only that very object even could exemplify. If you think that there are haecceities in this sense, then you can say that Globea and Globeb have different properties because Globea exemplifies one haecceity—Globeaness, say, or maybe the property of being Globea—while Globeb exemplifies another haecceity—Globebness, say, or maybe the property of being Globeb. So long as Globeaness and Globebness are distinct (and given the above characterization of haecceities, they must be distinct), Globea and Globeb have different properties. Thus, they are not qualitatively indiscernible. IOI does not, then, require us to say they are one, and we are left with no counterexample to IOI.

The trouble here is understanding the sense in which haecceities can be thought of as qualitative. Up to this point, we haven’t directly addressed the very important question of what indiscernibility is. The time has come to do so, because it is the only way to see why the failure of haecceities to be qualitative matters to our discussion. So, we will proceed in two steps. First, we will consider why Platonism urges us to think of properties as qualitative. Second, we will consider why it is unlikely that haecceities are qualitative.

The most natural way to find one’s way to Platonism goes something like the following. First, you make some alarmingly mundane observations about the world, observations like, “Hey, look at all those trees,” “I really like playing baseball,” “I really like orange things,” and so on. Then you notice something interesting about all these observations: each concerns a type of thing (tree, baseball game, the color orange, etc.). Further, these types are associated with the resemblances among things of that type or the causal powers possessed by things of that type.11 Finally, it is this connection between types and resemblances or causal powers that leads us to use words like ‘feature,’ ‘attribute,’ ‘quality,’ ‘universal,’ and ‘property’ in place of the word ‘type.’ Which is to say, Platonism is fundamentally motivated by a desire to explain the resemblances and causal powers of things by reference to their properties. And so, for the Platonist, there is a connection between one’s view of properties and one’s view of the qualities of things, where we understand qualitativeness in terms of resemblance and causal powers.12 In light of all this, when the Platonist formulates IOI, she means to have in view the sorts of properties that are qualitative, that make for resemblance or causal powers. The notion of indiscernibility in play is that of qualitative indiscernibility. Properties that do not make for resemblance or causal powers are therefore irrelevant to the question whether this and that are indiscernible.

It’s clear that haecceities cannot make for resemblances. Indeed, it is precisely this possibility that the introduction of haecceities was meant to prevent. Haecceities are, ex hypothesi, not the sort of property that more than one object can have. Therefore, they cannot be part of an account of some resemblance between two objects. Nor do haecceities seem like the sort of property that could make for causal powers. If there were causal powers conferred by haecceities, they would have to be causal powers that only one object could even possibly possess. It is very unlikely that there are any such causal powers. Causal powers seem sharable. The best case scenario for proponents of haecceities is that they bear a significant burden to defend the claim that, for every substance, there is some causal power that only that object has, and that only it could even possibly have. No proponent of haecceities, of which I am aware, has even attempted to discharge this burden.13 So it is clear that haecceities cannot make for resemblances, and unlikely that they make for causal powers. In which case, they are likely not qualitative.

Here, then, is where we stand. Constituent Ontologists who are also Platonists cannot be Bundle Theorists, for Bundle Theorists of this sort must, given PCI, commit to IOI. But IOI is very likely false because there could have been distinct but qualitatively indiscernible objects. It does no good to push back against the idea that these possibilities involve indiscernible objects by appealing to relational properties or haecceities; these “properties” cannot do the work they must do in this context. However, Bundle Theory is a very natural solution to The Problem. What to do?

The way to go is to reject one of Bundle Theory, Platonism, or PCI.

By now, you’ll know that J. P. would think it a bad idea to give up Platonism. I won’t rehearse his reasons here, and we will proceed as if Platonism were true.

Further, PCI is quite plausible for those committed to Constituent Ontology. Constituent Ontologists maintain that one can say what a substance is by cataloguing its constituents.14 If that’s right, though, it’s difficult to see how you could say what two substances are by offering but one such catalogue. If you’ve truly said what each substance is when you’ve produced the relevant catalogue, then substances and catalogues should be in one-to-one correspondence. Different substance, different catalogue. This is the thought that PCI is meant to express.15 16

Summing up: IOI is out, and Platonism and PCI are in. We must consider abandoning Bundle Theory. As it happens, this is the choice J. P. makes. In particular, J. P. appeals to “bare particulars” to solve The Problem.

What are bare particulars? First, they are particulars, and in that way are like you and me and all the substances about which we’ve been talking. Particularity is conceptually fundamental—we are at the limits of conceptual explanation here—so there’s nothing more to say than to group bare particulars together with other familiar objects that we count as particulars, and point out that they are, with respect to their particularity, in the relevant group. Second, though, bare particulars are bare. There are two dimensions of the bareness of bare particulars. They are bare in that they are not properties, which is to say that bare particulars do not characterize anything. No bare particular makes it the case that something other than itself has a certain feature: they do not ground character.17 The second dimension of the bareness of bare particulars is that they are not themselves charactered by anything. This is where the difference between bare particulars and other, familiar particulars emerges: substances have character, whereas bare particulars do not.

However—this is going to sound strange—bare particulars do “have” properties. J. P. talks about this in a particularly helpful way. Consider (1):

(1) Elsie is a dog.

(1) is, according to J. P., “grounded in” (2):

(2) Elsie’s bare particular, b, is “tied to” the property of being a dog.

But what does it mean to say that b is “tied to” this property? Well, according to J. P., this is to say that b exemplifies the property of being a dog in a “strict, philosophical” sense. This strict, philosophical sense of exemplification is unlike the way that the substance Elsie exemplifies that same property: Elsie has the property of being a dog as a constituent. Importantly, the property of being a dog gets to be a constituent of Elsie—and, as we will see shortly, thereby gets to characterize Elsie—precisely by being tied to b, Elsie’s bare particular. So this relationship into which properties and bare particulars enter, the relationship J. P. calls strict, philosophical exemplification, is rightly dubbed as a type of exemplification because it is crucially connected to the fact that certain properties characterize substances. Since bare particulars exemplify properties, it’s right to say that, in this sense, they “have” properties.

There is a vital point that cannot be, but often is, missed: the sense in which bare particulars have properties is not the sense of having a property that makes it the case that something is charactered by the relevant property. Constituent ontologists who argue themselves into a commitment to bare particulars ought to think that a property P characterizes some object o just in case P is one of o’s constituents, and that this constituent-whole relationship between properties and objects never happens with bare particulars. We can see this by thinking about the natural approach to constituent ontology with bare particulars. Start with an ordinary substance, which clearly has certain characteristics; it is a charactered thing. One then accounts for that character by saying that the substance’s characterizing properties are constituents of that substance. But then you run into The Problem, and you go in for bare particulars. You cannot then say that bare particulars have constituents as well, otherwise you’ll have reinstated The Problem with respect to bare particulars. But bare particulars, given the logic of their introduction, must solve The Problem. (Otherwise, you shouldn’t have gone in for them in the first place.) Thus, bare particulars never have constituents, and therefore don’t have character.18

I should be clear about the way in which bare particulars offer a solution to The Problem for the Platonist committed to Constituent Ontology. What individuates substances from one another—what makes each one and distinguishes it from all the others—are bare particulars. Bare particulars are constituents of substances that, in keeping with PCI, supply a way to distinguish, for example, Globea and Globeb. Ex hypothesi, Globea’s bare particular is not identical to Globeb’s bare particular, and so despite that Globea and Globeb are indiscernible, one needn’t concede that they are identical: happily, IOI can be false if bare particular theory is true. And, if J. P. is right, bare particular theory is true!

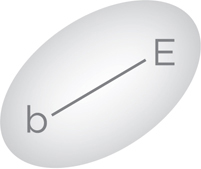

At any rate, a view of the metaphysics of the essential structure of substances emerges from all of this. The essence of a substance consists of a bare particular tied to one or more essential properties. A substance is not identical to its bare particular! I like to picture this view as in Figure 1, where the curved closed plane figure represents the “boundaries” of the substance’s essence, “b” represents its bare particular, “E” represents its essential property (the generalization to many essential properties should be obvious), and the straight line represents the tied-to type of exemplification relation:

Figure 1

The elements contained within the boundaries are meant to be the constituents of the substance’s essence. Figure 1 therefore displays, without appealing to a unique representational element, the idea that a substance’s essential features are constituents of that substance; thus, it is right to say that, according to Figure 1, the substance is characterized by those essential features.

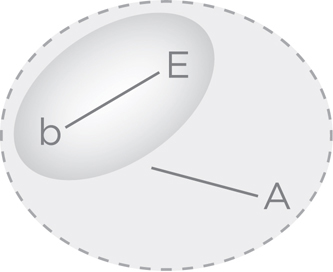

From here, there are difficult and delicate questions about the relationship between substances and their accidental features, features such that, if they are had by a substance, the substance might nonetheless fail to have. This is not the place to address those questions in detail.19 However, we will shortly be in need of a view, and so I will suggest that we think about accidental features as in Figure 2, where the representational elements are as before, with the addition of an “A” to represent a substances accidental feature(s), and the dashed closed plane figure representing the “boundaries” of the substance as a whole:

Figure 2

The idea here is that a substance’s accidental features are tied to the substance’s essence, rather than being tied to the substance’s bare particular.20

The time has come to switch gears a bit: I’d like to see whether all this fuss about a bare particular theory of substance can be put to work in articulating a coherent, orthodox theory of the incarnation of the Eternal Word. In particular, I’m interested in thinking about whether we can, using the picture we’ve developed of the nature of substance, get a grip on what it is for one substance to have two natures. We must, of course, think that the idea of one substance with two natures is coherent if we are to articulate an orthodox metaphysics of the incarnation. According to the Council of Chalcedon (451), the Incarnate Deity was such a being, and Chalcedon sets certain boundaries about Christological orthodoxy. Here is an English translation of the Chalcedonian confession:

We confess one and the same our Lord Jesus Christ … the same perfect in Godhead, the same in perfect manhood, truly God and truly man … acknowledged in two natures without confusion, without change, without division, without separation—the difference of natures being by no means taken away because of the union, but rather the distinctive character of each nature being preserved, and combining into one person and hypostasis—not divided or separated into two persons, but one and the same Son and only begotten God, Word, Lord Jesus Christ.21

We will focus here on how one person can have two natures in this way.

Before we directly address this question, I’d like to emphasize two interrelated points. First, I don’t intend to offer a mandatory Christological picture, one an orthodox believer must accept if she is to maintain the Chalcedonian formulation. Indeed, I don’t even pretend to be offering a full-blown Christological picture. There will be numerous issues on which the following will be silent. I am only concerned to articulate one way for a single substance to have two distinct natures. Second, I do not mean to offer the following partial Christological picture as one that I myself endorse. The most I am willing to say is that this picture displays that the incarnation is not incoherent on the dimension the picture is addressing. Putting these together, we can say that I am not proposing that the following picture is mandatory or true, but am proposing that the following picture is possibly true.

Enough with the hedging; let’s get on to the picture.

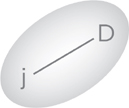

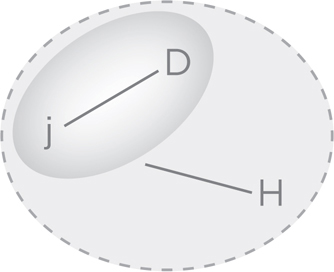

A view of the Incarnate Son that is suggested by J. P.’s bare particular theory of substance goes like this. The Eternal Logos, prior to His incarnation, was a divine person in virtue of having an essence composed of a bare particular tied to the property of being a divine person.22 Figure 3 is meant to capture this view, where “j” represents the Logos’s bare particular and “D” represents the property of being a divine person, and where the rest of the representational elements are as in Figure 1.

Figure 3

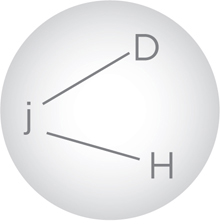

So far, so good.23 The question now becomes how we ought to understand the change that occurs when the Pre-existent Son incarnates. One idea that might seem plausible is to think that, in the incarnation, the Eternal Logos takes on a human nature in virtue of j’s coming to be tied to the property of being a human. Letting “H” represent this property, we find ourselves with the picture captured by Figure 4:

Figure 4

However, this picture will not do. The solid closed plane figure, recall, represents the “boundaries” of the represented substance’s essence. The Incarnate Christ, however, is not essentially human, in the sense that it is possible for the Incarnate Christ to fail to be human. This should be uncontroversial, and has been in the history of Christian theology, precisely because the Incarnate Christ just is the Eternal Son. That is, the Incarnate Christ is identical to the Eternal Son. In taking on a human nature, the Eternal Son did not cease to be. The Incarnate Christ has a human nature, of course, but unlike with we mere humans, that human nature is not essential to Him. The upshot of this is that, if Figure 4 represents the Incarnate Christ’s essence, then the Eternal Logos and the Incarnate Christ cannot be identical. Either the Eternal Logos ceased existing at the incarnation, or a fourth divine person came to be at the incarnation. Both options are theological disasters, and so we must reject the picture represented by Figure 4.

One lesson of the foregoing is that, whatever happened with the incarnation, it cannot be taken to change the essence of the Eternal Son (that is, the essence of the Incarnate Christ). The Son’s taking on a human nature cannot mean that the property of being human comes to be a constituent of the Son’s essence. The property of being human must be accidental to the Son. Recall, then, Figure 2 above. It suggests the metaphysics of the incarnation pictured in Figure 5, where the representational elements are as above:

Figure 5

Here, the property of being human is tied to the essence of the Eternal Logos, rather than to His bare particular. This is as one would expect, given the view of accidental features pictured in Figure 2 and the argument above that the Incarnate Word must be only accidentally human.

It is worth emphasizing, however, that according to the view pictured in Figure 5, the Incarnate Word is fully human and fully divine but one person. The “distinctive character,” sometimes translated “the property,” of a divine nature, D, is preserved, and is had by the Incarnate Word in just the way that it is had by the pre-incarnate Eternal Logos, namely, by being tied to the Eternal Logos’s bare particular, j. “The property” of a human nature, H, is preserved, in keeping with Chalcedon, and it is exemplified by the Incarnate Word. Thus, the view is not Apollinarian. Whatever comes along with having a complete human nature comes along in virtue of a thing’s having the property of being human, that is, H. (Recall that H may represent a cluster of properties.) Nothing of what it takes to be human, therefore, is had by the Incarnate Word in virtue of His exemplifying the property of being a divine person, that is, D. Further, the view is not Nestorian: there are not two persons here. This is where we have an obvious payoff of the discussion of individuation. There is only one bare particular, j, and so there is only one substance. The Incarnate Word is therefore not a human person, despite being fully human. Human persons are substances composed of a bare particular tied to H, whereas the incarnate Word is a divine person (a bare particular tied to D) who also has a fully human nature in virtue of exemplifying H contingently.24 Summing up: this view of the Incarnation gives us one person with two unconfused natures, just as Chalcedon demands.

And so we see that not only do bare particulars give us a way to solve The Problem, but they also give us some traction in articulating a coherent, orthodox metaphysics of the Incarnation, at least with respect to the idea that one substance can have two natures. That, anyway, isn’t a bad start!

1. I owe a debt to a great many people who have helped me think better about the subject matter of this paper; there are too many to list. But a special thanks to Robert Garcia and to the editors of this volume, Paul Gould and Rich Davis. My greatest debt, though, is to J. P. himself. He was my first philosophy professor, and he has been a constant source of knowledge, encouragement, and wisdom since the Fall of 2000, when I was twenty-one years old and in over my head during his metaphysics course. I wouldn’t be half the philosopher I am today without his influence.

2. I should flag an assumption that will later come up against a challenge. The assumption is that if something is a universal, then it is shareable. (See the section on haecceities below.) Also, the word Platonist has a number of senses in the philosophical literature, many of which are more demanding than my usage here. So to be clear: all it takes to be a Platonist in the sense I have in mind is a belief in universals. None of my arguments will turn on the further demands that sometimes are associated with the word.

3. When I say “non-mereological,” you might just think “non-physical”: later, where I say “mereological,” you might just think “physical.” These aren’t quite equivalences, but the differences won’t matter for what I’m about here.

4. Bundle Theory, Platonism, PCI, and IOI are more or less terminological variants of the (1–4) one finds, e.g., in J. P. Moreland, “Theories of Individuation: A Reconsideration of Bare Particulars,” Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 79.3 (1998): 252; J. P. Moreland, Universals (McGill & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001), 141; and J. P. Moreland & Pickavance, “Bare Particulars and Individuation,” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 81.1 (2003): 2.

5. But see Gonzalo Rodriguez-Peryera, “The Bundle Theory is Compatible with Distinct but Indiscernible Particulars,” Analysis 64.1 (2004): 72–81.

6. There is a second problem in this neighborhood: this account of individuation doesn’t tell us what makes a substance one; we are lacking an account of a substance’s unity. I think this problem is quite nasty for Bundle Theorists, but it has received less attention than IOI. Here on out, we’ll ignore it.

7. My argument here bears close resemblance to arguments in Max Black, “The Identity of Indiscernibles,” Mind 61.242 (1952): 153–64, and Robert Adams, “Primitive Thisness and Primitive Identity,” Journal of Philosophy 76.1 (1979): 5–26.

8. “Homogenous iron globes aren’t substances!” Maybe not, but it’s easy to construct an analogous scenario, one that makes just this trouble for IOI, involving two examples of your favorite type of substance (except God, of course). My choice is doing no substantive work.

9. There is an exception to this rule, namely when the relations stood in are constitutive of the objects in question. (This points further to the connection highlighted between individuation and necessity in the second problem for this first strategy.) When the very existence and identity of a thing is in view, then relations needn’t presuppose their relata. For example, J. P. thinks that existence is (roughly) the having of a property. This means that, when something comes to be, it thereby must come to have a property. Take, then, an object and its essential features, the features it couldn’t fail to have. The exemplification relation between the object and those properties cannot presuppose the existence of the object, since in order to exist, the object must have those properties.

10. The mistake here is in thinking that the facts about an object which allow us to tell one thing from another are the facts about an object which make the object one. We should not confuse epistemology for metaphysics in this way.

11. Compare David Lewis, “New Work for a Theory of Universals,” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 61.4 (1983): 343–77.

12. There is much more to say, but this is no place to say it. Importantly, I’m talking about one way to arrive to Platonism, not more generally a way to find one’s way to a theory of properties. Just as importantly, I’m more or less stipulating that there is a connection between qualitativeness, on the one hand, and resemblance and causal powers, on the other. I do, however, mean to motivate (not defend!) a connection between properties and qualitativeness. Further, I do not mean to say that properties have causal powers. All I wish to commit myself to is that we explain the causal powers that things have by appealing to their properties.

13. But see Timothy H. Pickavance, “The Natural View of Properties of Identity,” in Robert Garcia (ed.), Substance (Munich: Philosophia Verlag, forthcoming).

14. Strictly speaking, one must also specify the interrelations among the substance’s constituents. I’m ignoring this needless complication.

15. Rodriguez-Peryera, in his “The Bundle Theory Is Compatible with Distinct but Indiscernible Particulars,” denies PCI as a way to make Bundle Theory and IOI compatible.

16. Still further, PCI is similar to an equally plausible principle having to do with mereological parts: if every mereological part of a is a mereological part of b and vice versa, then a is numerically identical to b. This principle has its detractors. But no one denies that it is initially plausible.

17. Readers familiar with the idea of “tropes” can note that this is one way in which tropes and bare particulars differ.

18. See Pickavance “Bare Particulars and Exemplification” (ms.) for more.

19. But see Pickavance (ms.).

20. This is not in keeping with certain things that J. P. says, though he has never directly addressed these issues in print.

21. Taken from Michael Murray and Michael Rea, “Philosophy and Christian Theology,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2012/entries/christiantheology-philosophy/>.

22. I will assume in this case, and also with Christ’s humanity, that the essence of divinity and humanity consists in a single property. This is a simplifying assumption on which nothing of substance hangs.

23. Well, maybe. Some may be unhappy with the idea that the three Persons of the one Godhead are constituted by anything at all. I am not unsympathetic with this unhappiness; indeed, I myself would deny that bare particulars individuate the three Divine Persons. But for reasons that would go beyond the scope of this paper, I don’t believe there is anything unorthodox in this idea.

24. To be (perhaps painfully) clear: I am not saying the Incarnate Christ is less than fully human. I am saying He is not a human person. Human persons are mere humans, humans that are not sustained by a divine person in the way the humanity of Christ is sustained by the Logos. This is in keeping with the tradition on this matter.

I take it, though, that this is by and large a stipulation about the meaning of “human person.” If one would like to say that human persons are substances with full human natures, then the Incarnate Word would be a human person. I am using “human person” to cover only those fully human substances that are also, in the medieval terminology, “suppositums,” that is, “independently existing ultimate subject(s) of characteristics” (Alfred Freddoso, “Human Nature, Potency, and the Incarnation,” Faith and Philosophy 3.1 [1986]: 28). The human nature of the Incarnate Christ is not independently existing in the relevant way, as it depends for its existence on the Eternal Logos. Thus, the human nature of Christ is not a human person (that’s Nestorianism!); rather the Incarnate Christ is a divine person with a fully human nature. That is why the Church has been hesitant to call the Incarnate Christ a human person.

At any rate, notice that given bare particular theory, we can display the difference between “natures” that are suppositums and those that are not: natures that are suppositums are natures in which “the property” of that nature is tied to a bare particular, whereas natures that are not suppositums are natures in which “the property” of that nature is tied to a complex whole composed of a bare particular and “the property” of some other nature. For more on these matters, see Freddoso (Ibid.).