incontinence. (See Fig 43.1.)

incontinence. (See Fig 43.1.)Urology deals with surgical and medical diseases of the male and female urinary tract system and the male reproductive organs. The surgical procedures involved can be classified into those of the upper and lower urinary tract respectively. The majority of urological procedures are performed electively (e.g. as day-case procedures).

• trauma and reconstructive urology

• Transurethral resections (e.g. transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for prostate; transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT) for bladder tumours).

• Surgery for renal stones (e.g. lithotripsy in theatre, and extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) in the clinic).

• Paediatric urology (e.g. hypospadias, orchidopexy).

• X-ray (plain/contrast)/CT KUB/CT urography.

• Cystoscopy (i.e. flexible in clinic, rigid in theatre).

• Urethral/suprapubic catheterization (ward/ED).

• Bladder irrigation (specialist nurse clinic or on ward/ED).

• Urodynamics (often by specialist nurses in clinic).

• Digital rectal examination of prostate

• Urethral catheterization and attending trial without catheter (TWOC) clinic.

• Flexible cystoscopy on a model (ask the doctor whether you can navigate a cystoscope inside an upturned plastic cup with lesions drawn inside).

This is strictly the presence of RBCs in the urine. It can be classified into microscopic (i.e. normal urine colour) and macroscopic (i.e. looks red). Classify the causes anatomically (i.e. upper tract—kidney; middle tract—ureter; lower tract—bladder/prostate/urethra). The commonest causes are infection (e.g. cystitis, pyelonephritis), stones (anywhere along the urinary tract!), tumours (prostate, bladder, and kidney), autoimmune disease (rarer, e.g. glomerulonephritis), and postoperative (more common, e.g. after TURP).

Typically cause renal colic (a rapid, severe, sharp, and colicky loin-to-groin pain). You might often see dipstick haematuria, and if not, you would definitely need to think about the most common alternative causes (appendicitis, gallstones, (gynae) cyst rupture, bowel obstruction, gastroenteritis, etc.). Commonest sites of stone formation are at the narrowest sites: pelviureteric junction (PUJ), mid ureter, and vesicoureteric junction (VUJ). Predisposing factors include dehydration (think lorry drivers), infection (Proteus infections associated with large staghorn calculi), metabolic abnormalities (rare but exam favourites, e.g. hyperparathyroidism), congenital deformities (rare, e.g. horseshoe kidney), and familial. 80% of stones are radio-opaque (e.g. oxalate/phosphate) due to calcification (the other 20% include struvite, urate, and cysteine stones). Management depends on size of stone: stones <5 mm are likely to pass spontaneously where medication may offer symptomatic relief (alpha blockers); those >5 mm may require lithotripsy (in clinic) or extraction (in theatre).

This is the most common cause of bladder outlet obstruction, and often presents in elderly males with symptoms such as hesitancy, poor stream, frequency, and terminal dribbling. After the classical history, this diagnosis is assisted by DRE which identifies a smooth, symmetrically enlarged prostate. You should know how alpha-adrenergic antagonists (tamsulosin) or 5-alpha reductase (finasteride) work to alleviate symptoms. TURP may be necessary if the bladder is still functional and therefore will not  incontinence. (See Fig 43.1.)

incontinence. (See Fig 43.1.)

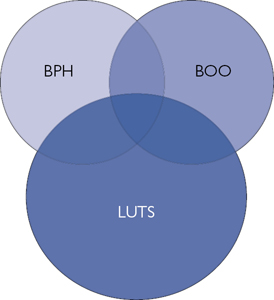

Fig. 43.1 The relationship between BPH, LUTS (lower urinary tract symptoms), and BOO (bladder outflow obstruction). The cause of LUTS is multifactorial; however, they remain the usual trigger for men to seek medical attention and may  a diagnosis of BPH, with or without evidence of BOO. Reproduced with permission from William E. G. Thomas et al, Oxford Textbook of Fundamentals of Surgery, 2016, Oxford University Press.

a diagnosis of BPH, with or without evidence of BOO. Reproduced with permission from William E. G. Thomas et al, Oxford Textbook of Fundamentals of Surgery, 2016, Oxford University Press.

This is a condition defined as the inability to retract the foreskin (over the glans). It is normal in <6-year-olds, but when (1) it persists, (2) it is associated with pain, or (3) there is swelling on urination, it can precipitate underlying infection (balanitis). It can be associated in adults with infections, as well as various skin conditions, in particular lichen sclerosis, and this can be an indication for circumcision. Remember, paraphimosis, is when the foreskin cannot be returned to its original position after retraction. This can occur if you forget to return the foreskin after urinary catheterization. The glans swells and becomes painful (due to restricted penile blood flow) and should be manually reduced (or rarely warrants emergent circumcision).

This is defined as the leakage of urine after  intra-abdominal pressure and is due to a weak urethral sphincter. This can be classified most commonly into stress, urge, overflow, and mixed. There are several causes, the commonest being pelvic floor weakness from childbirth and exacerbated by age in females, and BPH in males. Other causes include diabetes, stimulants (e.g. caffeine), and neuro-degeneration (e.g. multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, etc.). Try to understand abdominal vs bladder pressure traces during urodynamic testing, and how these can differentiate between the causes. Patient management begins with physiotherapy (i.e. pelvic floor exercises for stress incontinence) and medications (oxybutynin for urge incontinence), but surgery may be required (e.g. tension-free transvaginal tape).

intra-abdominal pressure and is due to a weak urethral sphincter. This can be classified most commonly into stress, urge, overflow, and mixed. There are several causes, the commonest being pelvic floor weakness from childbirth and exacerbated by age in females, and BPH in males. Other causes include diabetes, stimulants (e.g. caffeine), and neuro-degeneration (e.g. multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, etc.). Try to understand abdominal vs bladder pressure traces during urodynamic testing, and how these can differentiate between the causes. Patient management begins with physiotherapy (i.e. pelvic floor exercises for stress incontinence) and medications (oxybutynin for urge incontinence), but surgery may be required (e.g. tension-free transvaginal tape).

Consists of a vast range of conditions. Common ones include cryptorchidism (undescended testis associated with subfertility and malignancy), hypospadias, and vesicoureteral reflux (a common renal disease due to abnormal backflow of urine).

Involves cancer anywhere along the urogenital tract but commonly in the prostate (adenocarcinoma), bladder (transitional cell carcinomas), and kidneys (various types including clear cell tumours). Testicular tumours include germ and stromal tumours, teratomas in second decade (Troops) and seminomas in third decade (Sergeants). These are all incredibly variable, as are their investigations and the chemotherapeutic, radiation, and surgical management that may be used.

Commonly seen in clinic (and finals), including hydrocoeles (fluid within the tunica vaginalis, typically transilluminating), varicocoeles (dilated veins of the pampiniform plexus, typically feeling like a ‘bag of worms’), and testicular tumours. A good mantra is to consider a scrotal lump a cancer until proven otherwise, while an acute, painful testicular swelling is a testicular torsion until proven otherwise.

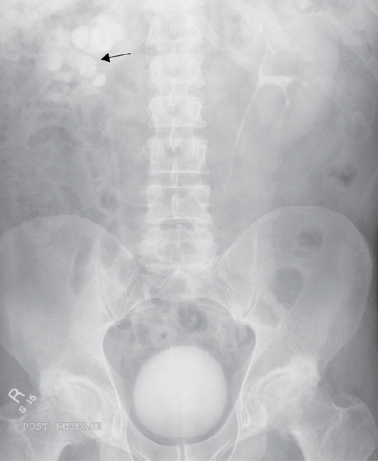

• Intravenous urography (IVU) was traditionally the investigation of choice for suspected abnormalities of the renal tract (especially the ureter) but has now been replaced by CT imaging (e.g. non-contrast CT KUB for renal stones, or CT urography for other renal tract abnormalities). Plain film KUB often accompanies a CT KUB to establish whether they can be identified so they can be used for follow-up. Always ask for a 15–30 min interval film in IVU, looking for a standing column to confirm a calculus. (See Fig 43.2.)

• US scans of the kidneys may demonstrate structural abnormalities (e.g. hydronephrosis, cysts). Transrectal US scanning is used for biopsy of suspected prostate cancer, and scrotal US scanning is used for suspected testicular cancer.

• MRI rather than CT can be useful in the assessment of the prostate gland (and seminal vesicles).

• Isotope renography provides anatomical and functional information about the renal tract. DMSA (dimercaptosuccinic acid) provides a functional image of the renal parenchyma, while MAG3 (mercaptoacetyltriglycine) renography provides dynamic assessment of renal excretion, and excludes the presence of obstruction.

Honours

Testicular tumours may present atypically (e.g. as testicular torsion or scrotal haematomas) but offer good prognosis if managed early. Teratomas are associated with raised serum alpha-fetoprotein and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), and are usually managed with orchidectomy and chemotherapy, while seminomas are associated with raised serum beta-hCG and are very sensitive to radiotherapy.

Fig. 43.2 An intravenous urogram demonstrating excretion of contrast material by the left kidney into the bladder. There is some excretion of contrast from the right kidney along with multiple, large, round radio-opaque lesions in the kidney consistent with multiple renal calculi (arrow). Reproduced with permission from Jolly, E. et al, Training in Medicine, 2016, OUP.

This is a central endoscopic procedure for urologists. Flexible cystoscopy is performed under local anaesthetic to examine the urethra and bladder, while rigid cystoscopy is performed under GA and allows for a greater degree of instrumentation. Cystoscopy (and ureterorenoscopy) can be used for insertion of retrograde ureteric stents, stone fragmentation/extraction, as well as tissue resection and biopsy.

This is a common procedure and may be performed under GA or local anaesthesia. Alongside hydrocele repair and other ‘lumps’, it can often be found on a theatre list of day cases and make for excellent cases to scrub in with and assist (make sure you know your relevant inguinal and scrotal anatomy beforehand).

This may resolve spontaneously or is amenable to drainage (often associated with recurrence): Lord’s repair (plication of the tunica vaginalis), Jaboulay’s repair (inversion of the hydrocele sac).

This may rarely be repaired by embolization.

This may be performed for certain advanced testicular tumours, or upon finding a non-viable testis during scrotal exploration for testicular torsion (find out whether the surgical access is via inguinal vs scrotal skin). If a testis is deemed viable during exploration, orchidopexy is commonly performed on both the affected and normal testes.

This is performed via rigid scopes and involves circumferential excision of the inner transitional zone of the prostate. It can be performed with traditional diathermy or more modern laser-based tools to excise/vaporize the prostatic tissue. Complications of TURP include haematuria (requiring bladder irrigation), retrograde ejaculation, incontinence, erectile dysfunction, and TURP syndrome. This procedure is not used for prostate cancer, which may require radical prostatectomy (via an open or laparoscopic approach) for curative intent.

This removes bladder tumours (together with intravesical BCG or mitomycin C). More advanced bladder tumours may be amenable to radical cystectomy (± chemotherapy or radiotherapy), but often begin with a TURBT for the purpose of obtaining histological information.

This is for (1) removing tumours of the proximal renal tract, (2) extraction from donor patients, and (3) cystic renal disease. Indication for benign or malignant disease determines the ancillary procedure (e.g. lymph node, vascular and ureteric excision).

This is performed by interventional radiologists, usually percutaneously, to decompress an obstructed (± infected) kidney.

Simple anatomies of the male and female reproductive systems are found in Fig. 43.3. Learn the basics which will be asked in theatre.

Fig. 43.3 (a) Male and (b) female reproductive systems. Reproduced with permission from Glasper, A. et al, Oxford Handbook of Children's and Young People's Nursing 2e, 2015, Oxford University Press.

Honours

• The irrigation fluid used for TURP and endoscopic procedures involving diathermy is usually glycine (instead of normal saline), due to its electrical non-conductivity and relative hypotonicity.

• TURP syndrome may occur after transurethral surgery, due to excessive absorption of irrigation fluid perioperatively  hyponatraemia (confusion, hypotension, bradycardia, vomiting, and collapse). The patient may need ITU support alongside ‘slow’ restoration of Na+.

hyponatraemia (confusion, hypotension, bradycardia, vomiting, and collapse). The patient may need ITU support alongside ‘slow’ restoration of Na+.

Presents as sudden pain in a hot, swollen, and tender testicle, occurring spontaneously in young males. This is a clinical diagnosis for which there should be a low threshold for suspicion. There is a 6-hour window to untwist the affected testicle after which the risk of testicular death (necrosis and subsequent subfertility likely due to an autoimmune phenomenon) is significant. Because it is a clinical diagnosis (Doppler), US is only supportive and not always done. Treatment is with surgical exploration (midline raphe incision or bilateral transverse scrotal incisions) for detorsion ± fixation (orchidopexy). Necrotic testes require orchidectomy.

Painful compared to chronic retention. May be secondary to prostate enlargement, clot, calculi, infection, and strictures. Confirmation of retention by bladder scanning may be helpful, but history and palpation/percussion should clinch the diagnosis, and catheterization will confirm while providing swift relief. Coude catheters, introducers, and cystoscopes aid in difficult cases. In the case of clot retention, a three-way catheter permits bladder irrigation to clear residual clots. Suprapubic cystostomy is reserved in case of contraindications.

This presents in a similar way to testicular torsion but is often subacute, and signs of infection may be evident on examination (e.g. penile discharge or pyrexia), urinalysis, and blood tests (e.g. raised inflammatory markers). Causes include (1) infections such as TB, STIs (e.g. chlamydia/gonorrhoea) in younger and Gram-negative enteric bacteria in older patients; and (2) recent catheter. Provided testicular torsion is excluded, treatment with antibiotics is commenced after sending urine for MC&S.

This is due to urinary calculi. Dipstick haematuria is highly sensitive for this pathology, and CT KUB is commonly used to confirm the diagnosis, establish the size/location, and guide treatment. It will be prudent to remember other differential diagnoses (especially ruptured AAA) when high-risk cardiopathy patients present with similar symptoms. Renal colic rarely occurs in the elderly, so always rule out AAA first with a history, examination, and imaging (e.g. bedside US scan in the ED or formal CT angiogram).

This is usually secondary to bladder or prostate pathology. Admission is warranted if blood loss is significant, if there is evidence of haemodynamic instability, and more typically for three-way catheterization and irrigation. The patient must be stabilized and able to urinate freely or via an unblocked catheter before being discharged. Most importantly, exclude malignancy with outpatient investigations.

Any examination of the urological system should be accompanied by an examination of the abdomen, hernia orifices, and include a DRE (i.e. for examination of the prostate).

Imaging—interpretation of plain film KUB or contrast IVU (i.e. to recognize renal tract abnormalities, calculi (e.g. staghorn), horseshoe kidney, or a duplex collecting system). Try to navigate CT urography on your urology attachment so you are used to tracing the renal system from kidneys down to bladders.

Urine dipstick testing is a common and simple procedure, and students should be familiar with the equipment involved and interpretations. Catheterization is a core skill which you should be able to talk through and demonstrate on female and male models including the reasons for each step.

Examining a testicular mass is a basic requirement, and you should be asking the following questions relating to the mass:

• Is it separate from the testis?

• Does it have a cough impulse?

• Consider indirect inguinoscrotal hernia.

• Is it cystic/solid (and does it transilluminate)?

• Cannot get above: inguinoscrotal hernia or hydrocele extending proximally.

• Separate and cystic: epididymal cyst.

• Separate and solid: epididymitis/varicocele.

• Testicular and cystic: hydrocele.

• Testicular and solid—tumour, orchitis, haematocele, granuloma, gumma.

• Signs pointing towards torsion:

• Prehn’s sign: lifting up the testicles relieves the pain of epididymitis (positive) but not the pain caused by testicular torsion (negative).

• Blue dot sign: tender and blue discoloured nodule on the upper pole of the testis (appendix testis or hydatid of Morgagni).

Honours

Foley catheters are made of dark yellow latex (beware allergies), are more flexible, and are for shorter-term usage than silicone catheters, which are clear in colour. Long-term catheters need to be changed every few months, and the formation of microbacterial biofilms is common; prophylactic ‘pre-change’ antibiotics may reduce the risk of infection at catheterization. If the patient is symptomatic of an infection they may require antibiotics but bacteriuria in asymptomatic catheterized patients is typical and should not be treated.