Up to this point, all of my emphasis in this book has been on getting the image right in-camera, and with good reason. Taking pictures is a lot like getting behind the wheel of a well-equipped car. Besides the “simple” task of getting behind the wheel, stepping on the gas, and steering the car in the right direction, you must also become familiar with all of the switches, dials, and buttons. Driving a car also requires a keen sense of what’s going on around you, but with practice and patience, you soon drive with confidence, by day or night and in all types of weather. Of course, there are those other drivers who jump the curb, run red lights, veer into on coming traffic, and speed constantly. These are the reckless drivers, the ones who keep the auto body shops in business.

Unfortunately, when it comes to digital image-making, many shooters are guilty of shooting with reckless abandon—with hardly a care in the world about learning what the camera is doing or where the camera is actually “taking” them. Part of the blame can be placed on the camera manufacturers and camera store salespeople who espouse the ease of taking pictures (“Just push the shutter release and the camera will do everything else for you”). But I can’t imagine anyone going into a car dealership and believing a salesperson who says, All you have to do is turn the ignition, face the direction you want to go, and the car will see that you get there safely.”

Yet a lot of shooters believe it’s possible to “just push the shutter release.” As a result, many of their images are like a car speeding the wrong way down a one-way street with no one at the wheel. Luckily, the “damage” effects solely the reckless “driver” (the photographer). And since no one else gets hurt by the reckless abandon of these photographers, they are slow to embrace a few of the simple rules about image-making.

In addition to the promise of picture-taking ease made by well-intentioned camera store salespeople and camera manufacturers, Photoshop and other photo-imaging programs are also guilty of perpetuating the myth that any damage can be fixed, no matter how grave. It seems the current mantra—said, with glee I might add, by the amateur photographer—is, “If I fail in-camera I can always fix the problem in Photoshop!” My response to this is, Photoshop is not an auto body shop!

Please don’t misinterpret me, as I’m a strong believer in the value of Photoshop, but why would you choose to spend time in Photoshop fixing all the damage that you could have easily avoided if you had simply steered your camera in the right direction? What is so hard about choosing the right aperture? What is so hard about using the right lens? What is so hard about paying attention to the time of day? What is so hard about paying attention to the background? What is so hard about placing one foot in front of the other and simply walking closer to your subject? What is so hard about turning the camera vertically when an obvious vertical subject is before you?

The time you invest behind “the wheel of” your camera will be time well spent in learning what your camera and lens can and cannot do—and this is particularly true of the digital SLR camera. How on earth can you not help but learn with the instant feedback of that LCD screen on the back your camera? Can’t you see that the horizon line is crooked? Good, so shoot another image—right now—with the horizon line straight. Can’t you see that the background shows the light pole growing out of your child’s head? Good, so change your point of view, or have your child move a few feet left or right and shoot another image—right now! Can’t you see that the exposure is way too “hot”? Good, so adjust your shutter speed a stop or two if you’re in manual mode, or adjust your autoexposure overrides to −1 and −2 and shoot two more images right now! Can’t you see that the lone flower you composed doesn’t even come close to filling the frame? Good, either change to a longer focal length or move in closer and shoot another image right now! The more “work” you get done in-camera, the more time you’ll have to truly “play” in Photoshop.

Having said that, despite your best intentions, some of your images will pick up a “ding” or a “scrape”—even the best “drivers” among us have a lapse in judgment, and this is certainly a reason to call upon Photoshop. But a ding or a scrape is a far cry from a head-on collision, and I want to stress—for the last time, I promise—that you should not think of Photoshop as an auto body shop unless you are in the business of restoring old photographs (those that are really old, faded, and torn).

Photoshop can however, be a valuable tool in customizing your images. In much the same way that an auto body shop can turn an ordinary car into a “custom car,” with flared fenders, chrome rims, metallic paint, tucked and rolled leather seats, plush carpeting, and even a musical horn, Photoshop can turn an ordinary image into one that’s truly extra-ordinary. And, as I’m sure the mechanics at the auto body shop would agree, it will save a great deal of time if you arrive at the shop with your ordinary car completely intact.

So, although Photoshop is said to offer more than one hundred ways to change or alter your image, I include in this chapter only those techniques that have proved the most fun, valuable, and, subsequently, useful. If you’re interested in really learning all there is to know about Photoshop, you won’t find that here. But, Photoshop and other photo-imaging programs are here to stay. You will never succeed in digital image-making without these software programs since they are a necessary part of your workflow.

For example, you’ll never “process” or print your results without them. Gone are the days of dropping off a roll of film at the photo lab and picking it up two hours later, leaving you with only the simple task of placing the pictures into the family photo album. But the added imaging-program “work” that’s now required is, for the most part, fun. I’ve met many shooters who report that digital photography has become a family affair, with more than just the picture-taker getting into the act. Perhaps the greatest benefit of digital photographic technology has been that tiny monitor on the back of the camera. When photographing family members especially, everyone is quick to take a look at the LCD, and then the race is on to get the pictures uploaded to the computer (for the larger view) and printed in living color or black and white (for all to see).

Although I’m a photographer from the old school (meaning, I still find creating the image in-camera more rewarding than doing it in Photoshop), I have noticed in the past year that I’m finding more reasons to spend time on the computer as I discover another useful tool or shortcut. While Photoshop is, for some, the primary tool for creating images of great emotion and feeling, I’ve found Photoshop to be no more or less important than a necessary filter or lens—all extend my range of creative image-making possibilities. Now let’s go have some fun in Photoshop!

PHOTOSHOP, PHOTOGRAPHIC TRUTH & INTEGRITY

And one final note about the use of Photoshop: Several months ago, one of my students asked my thoughts about ethics in photography and the use of Photoshop. His primary concern was about the truth of the photograph; for example, was that full moon really there when you shot that landscape or did you add it in Photoshop, or was that kid really running from the grizzly bear or was he actually running at the local park but you replaced the background with a charging grizzly bear? My answer may seem surprising since I’ve probably made it clear throughout this book that I’m a purist at heart and believe in getting the shot right in-camera, but as far as I’m concerned, the real “truth” of any photograph—as in all art—lies in its ability to evoke emotion. I could honestly care less if the image in question was made in-camera or in Photoshop.

Having said that, do I consider the use of Photoshop and the making of composites to be the truth? No. Yet many Photoshop composites have evoked some strong emotional responses from me—but this has been under the umbrella of knowing they were composites, and therein lies the difference. If we are led to believe that the photographer was very lucky in being at the right place at the right time and then we discover later that the phenomenal sky and rainbow were added in Photoshop, it hurts everyone in the industry for obvious reasons. I feel sorry for the truly lucky shooter who really was at the right place at the right time and got that “unbelievable shot,” since he or she is now looked upon with suspicion.

If you have added something to, or removed something from, an image in Photoshop, say so. And the same holds true even when you move something in, or add something to, the environment while composing a shot in-camera. Fair enough? That has been my philosophy, and I never hesitate to tell other photographers when any image of mine has been altered.

There is a plethora of image-editing software out there, and far be it from me to suggest that all of us use the same make and model. But my familiarity with image-editing software begins and ends with Photoshop, and for that reason, all of my tips and suggestions are based on, and relate to, the Photoshop platform. That doesn’t mean, however, that you can’t benefit from the information here if you’re not using Photoshop, but rather, you will need to investigate what and where the comparable features in your software are and adjust things for the specific nuances of your software.

For those of you who insist on shooting in JPEG FINE mode, and if you haven’t done so already, open up each of your keepers and immediately save them as TIFFs by selecting the Save As command and choosing TIFF as the new file extension. Before you do any work on any JPEG file, you should always save it first as a TIFF. Remember that a JPEG is a lossy file, meaning it loses data every time it is opened and/or altered; even if all you do is change its position from horizontal to vertical, the JPEG will lose a minute amount of data!

Once you have your folder of keepers, click on the folder to open it and view the thumbnail versions and sizes of the images contained in it. If you click on one of your keepers, it will open up in front of the thumbnails of the other images. Assuming you’re working with raw files, this is the stage at which you are given the option of changing your white balance setting (options are: Daylight, Cloudy, Shade, Tungsten, Fluorescent, and Flash). You may notice that when choosing a different white balance, the color temperature indicator also changes; in effect, your white balance setting has a great impact on the overall temperature of your image, making it appear either warm or cool.

In addition to affecting the color temperature with the white balance, you probably have the option of changing the color temperature via a separate control, independent of the white balance, and this is intended for fine-tuning the color temperature.

You also have the ability to change the overall exposure, and you can do this via a slider control or a simple arrow that you click; with each click, you can either increase or decrease your exposure in the highlights or shadows or both. Does this sound like a lot of work? It is, if you failed to set a correct exposure in camera or if you insist on shooting in auto white balance. Getting the exposure right in camera saves a great deal of time. And, as I mentioned previously, when the white balance is set to Cloudy, you will find very little reason to change it to something else in postprocessing.

Perhaps you felt as I did the first time you opened up an image only to discover that it was covered with dust bunnies. I know my lens was clean, and I know my subject wasn’t covered in dust, so where the heck did the dust come from?

Welcome to the world of digital, where the world of dust has found a new breeding ground! Digital photography, unlike film, does have one big drawback, and it’s this: Most digital SLR image sensors do a great job of recording an image, but they also attract dust like a magnet attracts metal. If there is a single dust speck anywhere near the image sensor, it will be attracted to the sensor.

To avoid dust, first and foremost don’t change lenses in a dust storm—in fact, don’t bother shooting in a dust storm at all! Second, turn off the camera every time you change lenses, since the static charge of this simple maneuver will draw dust right onto the sensor.

Despite your good intentions, however, dust will still eventually get in, and when it does, you can follow the manufacturer’s advice for getting the sensor cleaned, which in most cases will mean sending it in to an authorized camera repair service. This is certainly an option. Manufacturers say, in effect, that any other attempts to clean the sensor may not only damage the sensor but may also void the warranty. That’s a fairly strong warning, and whether you choose to heed it is, of course, up to you.

Whether you send your camera out for cleaning or opt to try my cleaning method (see box, opposite), you might leave the house with your camera free of the dust specks for now, but chances are good that one or several specks will work their way onto the sensor again—and you won’t always notice it until after you’ve downloaded your images onto the computer. Get used to it, at least for the time being, since most of the cameras on the market do not, as of yet, have dustproof sensors. And despite their annoying appearance, these dust bunnies will make it easier to embrace one of the quickest fixes for dust specks that Photoshop CS can offer: the Healing Brush.

Call upon the Healing Brush and, presto!, those dust specks are gone. Since I usually have to open my keepers in some kind of imaging software program to get them “ready,” I make it a point to enlarge the images to 100 percent. Using the sliders, or scroll bars, bordering the frame, I go up and down and side to side looking for any dirt spots. It takes but a minute at the most, and it’s a simple precautionary measure that makes sense, since most of my work is going out the door to a client or off to one of my stock agencies. Knowing my clients’ desire for clean images, I don’t want to hear from them that I need to clean up my act. If your interest lies in making prints of your work, you would be wise to do the same, since there’s nothing more frustrating than printing out an 11 × 14-inch color print only to discover that you have dirt near the outer petal of that yellow daisy.

The Healing Brush is quite simple to use. First, select it from the toolbox (it’s the one that looks like a bandage), find a dust-free part of your image that matches the area around the dust spot in both color and tone, and hold down the Option key on a Mac or the Alt key on a PC. (The cursor changes to a crosshair-like symbol when you do this.) Click on that dust-free area to select it as your source. Release the Option/Alt key and the mouse, and move the mouse to those pesky dust specks. Then “paint” over the specks by moving the mouse while clicking down on it, release the mouse, and voilà, your specks are gone. Note that when you do this, two cursors appear on the image: the circular one that you are painting with and the crosslike one indicating the area you selected as your source. Keep an eye on this latter cursor because any elements from the area it moves over may appear where you are “painting.”

The Healing Brush tool is different from the Clone Stamp tool (see this page) in that it also matches the texture, lighting, transparency, and shading of the source area so that the area you are retouching blends in seamlessly with the rest of the image.

HOW I CLEAN MY IMAGE SENSOR

I don’t know about you, but I don’t relish parting with my camera for a few days just to get it cleaned, so I came up with an easier solution to sensor cleaning. However, I will not take any responsibility for any damage that may result to your camera if you choose to follow my suggestion. In addition to your camera and lens, you’ll need a sheet of white paper and a can of compressed air.

1. Put the piece of white paper in a well-lit room, near a window perhaps, and then get your camera and lens ready. Set the aperture to f/22 and the ISO to the lowest setting (for example, 100), and take a picture of the paper, focusing as close as you can so that the frame is filled with nothing but the paper. If necessary use your tripod, and for this one tip, shoot in JPEG FINE mode, since that format will load quicker into the computer (see next step).

2. Now load this image into your computer, and increase the magnification of your monitor to 100 percent to see if any pesky black dust specks show up. (If you don’t see dust specks, the sensor is clean and you can move on to another section of this book—or keep reading for future reference). Assuming you see dust specks, turn off your camera, take off the lens, then turn the camera back on. Set the camera to manual-exposure mode and the shutter speed to the longest possible time (for example, 8 seconds, 15 seconds, or even 30 seconds, depending on make and model).

3. Set the camera on a table and with the can of compressed air in one hand, get eye level with the camera’s internal mirror. With your free hand, fire the shutter release for the longest possible exposure that your camera will allow, and with your other hand, fire several short bursts of air onto the now exposed sensor (it was hiding behind the mirror, which has now flipped up and out of the way since you have started an exposure). Obviously, you’ll want to time this so that you’re not firing bursts of air into the camera body while the mirror comes back down—if you do, the force of the air could cause your mirror to become misaligned. Also, do not shake the can of air at any time, since this could cause it to spit out “liquid air” and once this liquid air gets on the sensor, the Pixel Family is as good as drowned. It can be, devastating if you shake the can while blowing air onto the sensor; the cost of rebuilding the Pixel Family a new house (i.e., replacing the sensor) is not cheap, to say the least.

4. Turn the camera off, replace the lens, turn the camera on again, and take a picture of that white paper one more time, just to check to see if the sensor is really clean.

Imagine my surprise when, several days after taking possession of my first-ever digital camera (a Nikon D1X), I uploaded this image onto my computer only to be greeted by dust specks everywhere! I had made this image—one of my first attempts at shooting digital—through the window of a Boeing 777 just prior to descending through low clouds near Paris. The sunlight directly overhead was casting a shadow of the plane onto the low clouds below, and the added bonus of a circular rainbow was too compelling to pass up. I handheld my camera, set an exposure at +1 in Aperture Priority mode to compensate for the bright white clouds (the same thing I do when shooting snow), and proceeded to fire off several frames before the plane was soon immersed in the very clouds.

To clean the dust specks that appeared in the image, I chose a soft-edge brush and a size that was a bit larger than the dust specks themselves. The result is the image at right.

35–70mm lens, f/8 for 1/320 sec.

GETTING THAT “PERFECT” COMPLEXION

If you find yourself photographing people frequently, and you come across subjects who wish they looked younger or had a better complexion, there’s no better tool for the job than the Healing Brush, which can quickly reduce—if not eliminate—signs of aging, poor complexions, or unwanted beauty marks and moles.

What is, perhaps, the one most overused tool in all photo-editing software? The Sharpen tool! I can almost spot an oversharpened image in the dark, since every oversharpened image glows—and I do mean it glows! Why does it glow? Let’s take a look at the concept of sharpening.

First of all, if you’re looking to add one more reason to your get-it-right-in-camera list, sharpening should be the first thing you consider. Optical sharpness is—and will always be—about your lens and the quality of your sensor. In theory, the higher-priced lenses and higher megapixel cameras will combine to create the best optical sharpness. But, all digital images require some degree of sharpening, which is where software sharpness comes in. This is not to be confused with optical sharpness. Normal software sharpening is meant to serve one purpose: to bring out more detail in the sharpness and detail you have already captured. You will never be able to add detail by sharpening if the detail isn’t there to begin with, and therein lies the problem. In an attempt to compensate for a lack of image sharpness (due to camera shake with a slow shutter speed and no tripod or a lack of detailed focusing, for example), photographers will end up oversharpening the image.

Truth be told, sharpening does nothing more than create additional contrast around each pixel, giving the illusion that things are sharper. And oversharpening increases the contrast so much that each pixel gets a halo around it—and that’s why sharpened images glow. Unless you have plans to help Santa Claus and Rudolph find their way at Christmas with one of your “glowing” prints, make it a point to pay attention to focus and sharpness in camera.

If you must do some sharpening, what’s the best way to proceed without fear of generating halos? If you’re shooting raw and saving to TIFF, or if you’re shooting straight to TIFF, the rules are the same: Only after you’ve made all of your adjustments, fine-tuning, layering, color corrections, spotting, cloning, and so on, should you even think about adding some sharpness. Sharpening is always the last thing you do.

And note: Most digital cameras offer an in-camera sharpening feature that’s tied to the sensor. Every digital image, JPEG or raw, will always record a bit of softness due to the sensor having colored filters laid atop it. That’s right, colored filters! Although it’s not visible to the human eye, there is a checkerboardlike pattern of red, green, and blue filters on top of the sensor without which the sensor would only record monochromatic color. As film shooters already know, any filter adds a very small amount of softness to the image.

To compensate for this softness, you have the option of turning on the in-camera sharpening feature. In my opinion, you should turn this feature off, assuming you’re shooting in raw, since the default setting for in-camera sharpening (a setting you cannot change, by the way) may end up adding more or less sharpening than you want. It makes more sense to have the “freedom” to add any additional sharpness in post-processing. Unless you are shooting JPEGs (basic, normal, or fine), I see no reason to do any sharpening in-camera.

Since JPEG is a compressed file (and a lossy one at that), you should use in-camera sharpening before the file gets compressed. Adding sharpness later via the computer means opening the file up once again and losing data.

Most photo-imaging programs offer sharpening tools, such as Sharpen, Sharpen Edges, Sharpen More, and Unsharp Mask. Only Unsharp Mask offers a choice of how much or how little sharpening to add; the other three choices do it for you within preset parameters—and I have yet to find anyone who knows what those parameters are. This complete control over the amount of sharpness is the biggest reason Unsharp Mask is the favored sharpening choice. (And if you’re like me, the name Unsharp Mask conjures up anything but a tool that would make an image sharper—just the opposite, in fact; yet it is the sharpening tool that most photographers should use.)

To access Unsharp Mask in Photoshop, choose Sharpen from the Filter pulldown menu. The Unsharp Mask dialog box opens, and you’ll see three bars: Amount, Radius, and Threshold. Amount adjusts the intensity of the filter. Radius determines the size of the halo produced around each pixel—and is, thus, the most critical setting of the three. And, Threshold controls the contrast differences between pixels and tells the filter how similar or different the values need to be before putting down the sharpening effect.

Now, here’s where it can get tricky, because some photographers want to use one group of settings when they’re sharpening just one part of an image, and different settings when they’re sharpening up the whole image at once. Sharpening can be a whole chapter unto itself, and this book is not solely about photo-imaging techniques. In fact, I’ve only scratched the surface, so as someone who has never gone beyond the “norm” in the sharpening arena, I’ll just share with you my own personal settings (which I used for all the images in this book and which I use in all of my commercial work): I set Amount at 175 percent, Radius at 2 pixels, and Threshold at 4 levels.

Once you’ve finished cleaning up any dust specks, you can move on to other issues with your image. I’ll start with mergers. Try as you might, for example, you failed to see that the distant light pole merged with your son’s head. The poor kid looks like he has got a real headache, and you would too if you had to walk around all day with a light pole stuck in your head. Mergers are a common problem in photographic composition, more so for the amateur, but even us pros still fall into the trap of becoming so enamored by the subject before us that we fail to see that thing in the background that detracts from the subject itself.

No problem, thanks to the Photoshop Clone Stamp tool. With this tool, you can simply replace or cover that light pole with something else that’s nearby, such as blue sky. To do this (in Photoshop CS), you click on the Clone Stamp tool in the toolbox and then hold down the Option key (for Macs) or the Alt key (for PCs). As with the Healing Brush, you’ll see the cursor change to a crosshair-like symbol. While still holding down the Option/Alt key, place the cursor over the part of the image you want to use for cloning (in this case, some blue sky) and click on the mouse in that spot. Then release the Option/Alt key. The cursor will change to a small circle. Using the mouse, move that circle to the area you want to cover (in this case, the light pole). Press down on the mouse and use short back-and-forth strokes to go over the light pole, changing it to blue sky. Again, as with the Healing Brush, note that when you do this, two cursors appear on the image: the circular one that’s applying the blue sky and a crosslike one over the original blue source area that’s being copied (where you initially clicked your crosshair mouse to assign blue sky to it). Keep an eye on the latter cursor because it indicates what area is being cloned over the light pole. If it moves over, say, a bird in the sky, that bird will be cloned where the light pole is, instead of just blue sky being cloned.

It’s a really easy fix, as long as the brush size corresponds to the working area. (Brush size can be accessed and adjusted from a pulldown feature on a bar just under the menu bar at the top of the screen.) Too big of a brush size, and just like that, in one sweep, both the light pole and your kid will be gone. (That’s no problem, though, since Photoshop keeps a history of your actions, and you simply have to go to the history menu, click on the previous step, and the program undoes the mistake—like it never happened. Photoshop also has a Step Backward feature, which continually undoes whatever the last action was.)

Learning how to use the Clone Stamp tool does take practice, not much, but practice nonetheless. And here’s bit of a warning: Both the Clone Stamp tool and the Healing Brush tool have become obsessions for many shooters who aspire to perfection. Before they know it, several days have passed while they’ve sat fixated in front of their computers, forever trying to make every nuance, down to the last pixel, perfect! Knock it off, and go feed the kids!

VIEW AT 100%—ALL THE TIME

Whenever I’m cleaning up an image using the Healing Brush or removing/adding small details using the Cloning Tool, I make it a point to work on the image at 100 percent magnification. At this level of magnification even the smallest of dust specks and other anomalies can be called out of hiding.

Sometimes, you need to make minor alterations in your digital images, and more often than not, the solution lies in using the Clone Stamp tool, the Healing Brush tool, and the Hue and Saturation controls. I made a total of ten minor changes to this image, taking all of five minutes. Basically, I used the Healing Brush and Clone Stamp tools to remove the distracting small areas of light in the dark shadow areas and also the slight “dings” on the metal pole. In addition, I used the Hue and Saturation controls to change the color in both the sky and the yellow sign, making them a little richer. (To expose this image, I metered off the blue sky in the left of the frame and then recomposed to get the final image.)

12–24mm lens, f/16 for 1/25 sec.

Photoshop offers many options in the arenas of both color and black and white. Sometimes, your digital image needs a simple tweak in its color, while at other times the light when you took the picture was not the light you had hoped for, so you the image needs much more serious tweaking.

I’ve found that for minor tweaking the Hue/Saturation adjustment controls offer the quickest and most effective solution, but be careful here, since many beginners get really carried away with the level of saturation. Too much saturation looks like too much saturation, and no matter how compelling your composition, it will look, first and foremost, like an image with too much saturation. Keep in mind to make it believable, not unbelievable.

The Hue/Saturation controls are found under Adjustments in the Image pulldown menu. The best way to see which colors you might want to adjust is to open the Hue/Saturation window on your screen and move the slider for Saturation all the way to the right. Make a note of which colors you’re seeing where, and then move the slider back to the center (so that the number in the Saturation box reads 0). Now, go into the individual colors in Hue/Saturation in the Edit pulldown menu and adjust them accordingly. Play around with this feature for practice to get the hang of it.

An example of when I might use Hue/Saturation is when I’ve found myself “burned” by the weather, when my hoped-for low-angled, golden sunset light never materialized due to an incoming storm. I shoot away anyway, as I always do, with the hope of perhaps adding the tone and color of the light that I had been seeking to the photograph later in post-production. For these situations, I call upon the Selective Color adjustment controls, which are also found under Adjustments in the Image pulldown menu (further down beyond Hue/Saturation). They allow me to emphasize (or de-emphasize, as the case may be) specific colors in a scene in much the same way the Hue/Saturation control does—but with even greater latitude.

A word of caution here: You can make the light in any given scene look warm, as if you took the image shortly after sunrise or during that golden hour of light before sunset, but if your scene has no shadows, it will look like a cheap rendition of a sunny day.

Photoshop CS has made it even easier to get those warm colors I love. With the upgrade from Photoshop 7 to Photoshop CS, Adobe added a whole set of adjustments that resemble the filters you’d use on your lenses. And, the best part is that they are available as adjustment layers, so you can apply them to your image and then mask out areas you don’t want to be affected by the filter.

So, want to add warmth to an image you took in open shade? On your Photoshop CS menu bar, click on Image, then Adjustments, and then Photo Filter. You’ll get a choice of eighteen filters to use on your image, including several that warm things up. You can vary the intensity of these filters; and if you use an Adjustment Layer to add the filter effects, you can apply those filter effects to select parts of your image by using a layer mask. To do this, select any of a number of tools from the toolbox (for example, the Elliptical Marquee tool, the Lasso tool, the Magic Wand tool, and so on), and using the mouse, select an area where you would like to apply a filter effect. The area will be indicated by a dotted line. Then choose Layer on the pulldown menu bar, then New Adjustment Layer, and then Photo Filter. Once the filter list comes up, you can choose your filter for that selected area.

If there’s one constant for every outdoor/nature photographer, it’s the ever-changing light and weather. After enjoying clear blue skies and sunshine for the better part of the day, I noticed a large looming storm approaching. It wasn’t long before the sun and my hoped-for low-angled, warm light disappeared (top). So, I added, via Photoshop, the color and tones I was unable to record due to the incoming storm. The combination of the Selective Color tool and the Hue/Saturation controls allowed me to come close to getting an image that looked like a scene Mother Nature could have created on her own had the storm not gotten in the way.

200–400mm lens at 300mm, f/22 for 1/90 sec.

Sometimes, you don’t discover that a particular image may have looked better in black and white until you load it into the computer. In Photoshop, this is, once again, not a problem. Although there are many sophisticated Photoshop features you can use (you can buy a comprehensive Photoshop book that details all that), I simply call upon the Desaturate control under Adjustments in the Image pulldown menu, and the color image becomes black and white.

I’ve told many students over the past three years to create a folder on their computers of twenty or thirty color images and then, just for the fun of it, open each one in Photoshop and apply Desaturate to see what they think. It’s another example of the great way that Photoshop can help rescue some possibly ho-hum color shots and reveal them to be real winners when seen in black and white.

And, if you don’t want a black-and-white image, but rather an old fashioned, sepia-tone print or a steely blue print, you can do that in Photoshop, as well. After using Desaturate, go to Color Balance (also under Adjustment in the Image pulldown menu) and move the Cyan/Red slider all the way to the right and the Yellow/Blue slider all the way to the left. Just like that, it’s a sepia-tone image. Or, move the Cyan/Red slider all the way to the left and the Yellow/Blue slider all the way to the right, and presto, you now have a steely-blue image. Is this fun or what?!

The original version of this image was a color slide that I made several years ago on assignment in Ukraine. After scanning the image into the computer using my Nikon Cool Scan 4000, I was quick to see how it might look as a sepia-tone image. As you can see in the last image below, it has a feeling that harks back to another era. (I also tried it in black and white and steely blue, as well.) In addition, I made a copy of the image, applied the Gaussian Blur filter to it, and blended the two images together. This accounts for the image’s subtle glow.

So what do you do if you suffer from indecision? Hey, sometimes you take a photograph, and you can’t decide if it’s better in color or black and white, and rather than make one of each, consider the other alternative: Maybe it’s better if it’s both! In Photoshop, you can have the best of both worlds.

When combining color with black and white, choose one of your iffy color photographs. Next, pick which portion of it you’d like to see in black and white. Now you need to decide if you’re going to select either the area you want to keep in color or the area you want to make black and white; choose whichever seems like it would be less difficult to select. To actually select the areas, you can choose from one of several tools from the toolbox: the Lasso tool, the Magic Wand tool (good if the color of the area is fairly uniform), the Pen tool (good if your shape is complex), the Quick Mask Mode, the Paintbrush, or, if you use Photoshop Elements 2.0, the Selection Brush tool.

If using the Lasso tool, very carefully draw a line around the area you want to keep as color. Or, if the area you want to keep in color is a relatively uniform shape, you can also try the Magic Wand tool, which does the same thing as the Lasso tool but will do it for you with a single click of the mouse; but again, the shape must be uniform in tone, color, and contrast, otherwise the Magic Wand won’t encompass the whole area. Whatever tool you use, after you select the area with the tool, you’ll see those “marching ants” (like a dotted line) encircling it.

At this point, you should tell Photoshop to feather your selection, which softens the edges and makes the transition between the selected and unselected areas better. Go to the Select pulldown menu to find Feather, and choose something around 5 pixels for your amount.

If the area that you selected is the part of the photograph that you want to keep in color, go to Select again and choose Inverse. This will surround everything but the area of color with those marching ants. Then go to the Image pulldown menu, choose Adjustments, and scroll down to Desaturate. Voilà, you now have both a color and a black-and-white photograph all in one!

While driving through Arches National Monument last year, I spotted this lone climber from the road, pulled my car over, and immediately set up my camera and tripod. I liked the sense of scale that the lone climber brought to the surrounding cliff face but was not that thrilled with the absence of light (the entire cliff face was in open shade since the sun was off to the left and behind some even larger cliffs). Once I loaded the image into the computer, I used the Lasso tool and “drew” around the edges of the climber. I then chose Inverse from the Select pulldown, and this allowed me to Desaturate the entire image, turning everything except the colorful climber to black and white. Finally, I went to Color Balance (under Adjustments in the Image pulldown menu) and chose 100 percent Cyan and 100 percent Blue with the sliders, as you can see in the last image above, that somewhat dull cliff is now transformed into a very cold and steely blue surface. The contrast of blue with the brightly clad, yet small, climber creates a compelling juxtaposition of scale and texture.

80–400mm lens, f/8 for 1/320 sec.

If you’re feeling a real hunger for some Photoshop fun, then you’ll love something I call a digital sandwich. Like this name implies, you start out with multiple images (like two “slices of bread”), but you end up flattening them both and layering them one on top of the other so that they look like one (a sandwich). And you thought only kids have fun! You can use one image and layer it with altered versions of itself, or you can use two or more different images layered together. The simplicity of this technique will have you hooked on making digital sandwiches for months, if not years, to come. Pick any number of your shots, and you’ll be amazed at how a ho-hum picture can be transformed into a truly “wow” photograph!

If I’m using the digital sandwich technique on just one image, I make use of the Gaussian Blur feature. The first thing I do after opening up the image in Photoshop CS is choose Duplicate from the Image pulldown menu. Just like that, I have two identical images side by side. I then choose the Marquee tool from the toolbox, select the rectangular option, and highlight the entire duplicate image with it (the “marching ants” will appear around the entire perimeter of the second image). For the next step, I go to the Gaussian Blur option (from the Filter pulldown menu) and apply a radius of 50 pixels.

After the blur takes effect, I highlight the entire blurred version with the rectangular Marquee tool, go to the Edit pulldown menu, and click on Copy. Then I click on the original image (making it active), return to the Edit pulldown menu, and click on Paste. The blurry image now covers up the original, in-focus one. Then I go to the Layer pulldown menu, go to Layer Style and choose Blending Options. I click on the Blend Modes pulldown options, select Multiply, and, presto!, I now have my sandwich. Finally, I go to the Layer pulldown menu again and scroll down to Flatten Image. These two images have now officially become one, and I am free to make whatever Brightness/Contrast adjustments I feel I may need.

Although flowers are the number one subject for this Gaussian Blur sandwich technique, if you are open to trying it with almost any subject, you will make many new discoveries. A nice landscape in Beaujolais, France, becomes very dreamlike when sandwiched with the blurred version of itself.

80–400mm lens, f/16 for 1/160 sec.

This sandwich technique involves the careful selection of two or more completely different images that, when joined together, can make a new and wonderful single image. You follow the same basic steps as for the single-image sandwich, except you don’t use Gaussian Blur and you try other blending modes, including Overlay and Screen, as well as Multiply.

As you get better at this, you’ll find yourself paying much closer attention to which subjects work well sandwiched together while you are out photographing. I’m always on the lookout for those awesome blue skies with puffy white clouds—as well as sunsets, sunrises, and moons—that I might use later as part of a digital sandwich. Over a number of years, using both film and now digital, I have amassed a huge collection of these subjects, which I keep in a folder on my desktop and call upon to sandwich with other images that, on their own, fall short of the grade. Although there are many reasons to sandwich images, fixing images with “bad lighting” is my main incentive for sandwiching.

What can you get when you sandwich a midday overexposed shot of crashing surf along Oregon’s coast with an upside-down sunset from Bavaria, Germany? Following the same basic principles for making a sandwich with one image, I was able to create a scene of coastal beauty so real that it fools almost everyone who sees it. I made the original coastal image (top, left) with my 80–400mm lens on tripod, and deliberately overexposed it with the idea of combining it with one of the many sunset/sunrise shots in my collection (top, right). I also adjusted the color (above), and the result is shown below.

CREATING YOUR STAPLE OF SANDWICHING IMAGES

If you’re like me and have recently become a digital convert, then you no doubt have a plethora of slides or negatives at your disposal. Why not sit down and take the time to see what nuggets of gold are waiting to be mined for use in digital sandwiches?

To get the highest quality scans possible, it’s best to scan 35mm slides or negatives with a high-resolution slide scanner. A 50 MB output at 4,000 dpi is the norm, and a scan of this quality will easily produce a high-quality color print of up to 11 × 17 inches, as well as be commercially suitable for stock photography purposes. If you have lots of slides to scan, investing in a good-quality film scanner makes sense. However, there are also some newer flatbed scanners that do just a decent job scanning negatives and slides; just don’t expect the flatbed scanner to do a great job scanning 35mm slides and negatives.

Also keep in mind that your library of potential sandwiching images is not limited to only slide or negative images. There’s nothing to prevent you from sandwiching digital images with print film images. Once scanned into the computer, a digital image is a digital image—whether you created with a digital camera or with a scanner.

However, what is important is that any two (or more) images you sandwich be the the same size—otherwise they won’t line up correctly, and it often becomes necessary to use noise reduction software on the scan of the slide or negative before you can make the sandwich together with an image shot with a digital camera. Scanned slides and negatives are known for picking up some noise in the scanning process. This is especially true when scanning at very high resolutions, such as 4,000 dpi with a Nikon Cool Scan or 5,000 dpi with Minolta’s slide scanner. Both of these scanners offer a Digital Ice feature, and this in one feature that I highly recommend you turn on. It makes for a longer scan time, but it also produces a much cleaner scan. If you would like toe achieve the ultimate in high-quality scans without breaking the bank, check out the downloadable software from the great folks at www.hamrick.com. They even have software available that can turn your scanned slides into raw files!

Since the age of seven, I had always had this idea to take a picture of a group of cowboys on a prairie riding off into the distance, kicking up dust, under the light of a full moon. There was always something comforting to me about a night ride under a full moon, like you would see in The Lone Ranger. I didn’t learn until twelve years later, shortly after my brother Bill put a camera in my hand, that Hollywood made it look like the Lone Ranger and Tonto were riding at night under a full moon by simply shooting them in black-and-white under a harsh midday sun at severe underexposure. Well thanks to the wonders of Photoshop, I, too, can now create the night ride. And, in my version I’ve included the full moon!

As soon as I photographed these three real cowboys in eastern Oregon against the somewhat harsh backlight of a mid-afternoon sky, I knew it would make for a great sandwich. With my camera and 200–400mm lens on tripod, I set the aperture to f/11, and with the camera in Aperture Priority mode, a somewhat underexposed image resulted. Only a few months ago, and with this book in mind, did I finally add a moon, and I think it’s fair to say that it looks real enough.

Students often ask me how many variations of a sunrise, sunset, moonrise, etc., I make when I see one I like. Much to their surprise, I only shoot three variations. Using the Rule of Thirds grid as a guide, I compose three shots: one with the moon or sun in either the lower third of the middle column (A) or the upper third of the middle column (B); one with the moon/sun on either the lower third of the right-hand vertical grid line (C) or the upper third of the right-hand vertical grid line (D); and one with the moon/sun in the middle third of the right column (E).

Again, thanks to Photoshop CS, I can flip or rotate these compositions to “fit” with whatever image I’m using to make my digital sandwich, so there’s no need to shoot additional exposures with the moon or sun in other parts of the frame. I’ll deal with all the astronomers out there if and when I get complaints about the authenticity of my flipped, or otherwise repositioned, moons. But I am convinced that most of us wouldn’t know if the moon were upside down or backward when used as part of a sandwiched image.

Also, I much prefer to shoot the “full moon” the day before it is actually full, since it is still rising and often has a yellow cast, which makes for some wonderful contrast against a dusky blue sky. Note that a yellow moon shot against a dusky blue sky often looks more authentic in a digital sandwich than a moon shot against a black sky. (Note: Exposure for a full moon is f/8 for 1/250 sec with ISO 125.)

If you’re not able to get a clear shot of the almost-full moon against a dusky blue sky because the moon is not high enough in the sky yet, you can wait a few hours until the moon is higher in the sky. The sky will be black, but you can get an unobstructed view. If you do this, you only need to shoot one composition, but do so at varied focal lengths. Chances are you will be converting all that black sky to white (i.e., transparent) before making a sandwich or composite (see this page for more on this); if you don’t, all that black will block out the image with which you are sandwiching the moon. Then, once you have isolated the moon, you can simply move it with the Move tool, placing it anywhere you see fit. So, you don’t need all the different placements mentioned earlier. Making versions at different focal lengths, however, will give you a selection of moon sizes from which to pick.

Composites are a bit more complex than digital sandwiches, but many of the principles are the same. The chief difference between the two is that a composite normally requires that you “erase” (or make white) some things in the original images before the two (or more) photos can be blended effectively. Again, any area of a photo that you make white becomes, in effect, transparent, so when you sandwich that first image with a second image, the second image will show through the white/transparent areas of the first image.

You can achieve this “showing through” of the second image in several ways. For example, you can use the Paste Into feature under the Edit pulldown menu, or you can use the Blending Options under Layer Style in the Layer pulldown menu.

As previously mentioned briefly, when you are making a sandwich (or a composite) with an image that has dark areas, you may want to make those dark areas white. Any part of an image that is made white is, basically, transparent and will allow parts of other images to show through.

So, how to you change that dark sky around a moon to white, for example, in preparation for sandwiching with a sunset? You could use the Marquee tool. To do this choose the elliptical Marquee tool and use the mouse to drag a circle of “marching ants” around the moon. Use the directional keys to nudge the circle just where you want it. Then go to the Select pulldown menu and choose Inverse. This will highlight the entire background (everything but the moon). Then you simply choose White from the color palette, click on the Paint Bucket, and paint over the dark areas with the white. (If necessary, you can use the Brush tool to make touch-ups so that the white is covering all the black.)

Now, before moving on, go to the Select pulldown menu, and click on Inverse to get the marching ants only around the moon. Choose Select again, go down to Feather, set the Feather Radius to 10 pixels, and hit OK. Feathering softens up the abrupt edge of the moon that is the result of dropping out the sky to white. The image is now ready to be sandwiched.

Perhaps you’ve found yourself out and about with your camera and are fully aware of that dramatic sky in front of you but are having trouble finding a compelling landscape to go with it. It seems that more often than not, I see some truly incredible skies over lackluster scenes below. Or, I see compelling landscapes under dull gray or plain “perfect” blue skies.

With Photoshop, you no longer have to rely on luck to get both a compelling sky and a compelling landscape at the same time. This is where composites come in. But first, of course, you need to have both a good sky image and good landscape image at your disposal. So, there is a lesson to be learned here: Whether you come across only a great sky or only a great landscape, shoot them both, since you never know when the time will come that you’ll want to combine them to form a single image.

For this composite example, my ho-hum image is a wide-angle shot of a barn in the Bavarian hills surrounded by yellow dandelions and an unimpressive sky. I felt it would be just the kind of image that would make a perfect marriage with one of my wide-angle shots of a more dramatic sky. To do this, I first opened up the barn image in Photoshop. I quickly painted all of that lackluster sky white. I then decided that I wanted the dandelions to be “red poppies,” and since they are a distant enough element in the image, I could get away with the switch. So, I went to Hue/Saturation under Adjustments in the Image pulldown menu, selected Yellow from the Edit button, and moved the Hue slide to the left until the flowers turned red.

Next, I opened my good sky image, pressed Command + A to get the marching ant highlighting around the entire image, and selected Copy from the Edit pulldown menu. I then returned to the barn image, selected the Marquee tool, and touched the cursor to the white sky area, thereby selecting the sky, which became surrounded with marching ants. Then I chose Paste Into from the Edit pulldown menu, and voilà, all that white sky was replaced by the more dramatic sky. To finish, I used the Move tool to move the new sky around a bit so that the alignment looked as authentic as possible. Once I was satisfied, I selected Flatten Image from the Layer pulldown image. Are we having fun or what?

Graduated neutral-density (GND) filters, which hold back the light over part of your frame, have been used by photographers for more than ten years, and although Photoshop has been around for just a bit less time than that, the concept of using Photoshop to mimic the results of a GND filter didn’t seem to occur to anyone until only recently. It makes you wonder what other obvious tools Photoshop has that most of us are too blind to see.

As you know by now, I’m a strong advocate for doing it right in-camera and saving my Photoshop time for more productive things that I just can’t do in-camera—such as making color prints. However, there are those times when you walk out of the house without your GND filter, or when you come upon a scene with a horizon line so staggered (mountain peaks, for example) that the “straight line” of the GND filter can’t possibly block out all of the strong backlight, or when using the GND filter would end up blocking the exposure of foreground subjects that continue up and beyond the horizon line.

In these situations, the solution is so simple that I’m still amazed that it has only now dawned on photographers! Photoshop has been around since the early ’90s!

To use Photoshop as a GND filter, let’s imagine you’re on a field trip. You come upon a backlit storytelling composition, so you set your aperture to f/16 or f/22. Take a meter reading of just the backlit sunrise sky (or sunset sky if you’re not a morning person), and adjust your shutter speed until the camera’s light meter indicates a correct exposure. Write this exposure down. Next, take a meter reading of the landscape below the sky at the same aperture, again adjust your shutter speed until a correct exposure is indicated, and write this exposure down. Then, if you haven’t already done so, put that camera and lens securely on your tripod and compose your shot. You must use a tripod for this technique; without one, the image will never line up exactly when you put them together in Photoshop. I don’t care how steady you might think you are, if you want this to work, you will absolutely need to use a tripod.

Now you’re ready to shoot the exposure for just the sky. Use the first exposure you wrote down. I’ll call this image the backlight image. (Note: This process illustrates just another example of the importance of knowing how to use your camera in manual exposure mode.) Then, shoot your second image at the exposure setting you wrote down for the landscape. I’ll call this the landscape image. You’re done with part one. Once you get home, load both images into the computer, open both in Photoshop, and follow along with what I did for the examples here. You’re basically putting the image together in a way that allows for the correctly exposed parts of each version to appear in the final composite (just as a GND filter renders all parts of a tricky exposure correctly).

For the first image (top, left), I set a correct exposure for the strawberry fields in the foreground, and in so doing, rendered the predawn sky obviously “blown out”—heck, it’s basically white. (If this were a color slide, this area would appear almost colorless and transparent on the film.) In the second exposure (top, right), I set a correct exposure for the sky, and in doing so, rendered the foreground deeply underexposed, almost black. I then “painted” the underexposed foreground in the second image white, effectively rendering it transparent (middle, right), and sandwiched that version together with the first exposure (the one with the correctly exposed foreground). The result was good exposure overall, much as if I had used a GND filter on my lens (bottom).

Top, left: 17–55mm lens at 28mm, f/22 for 2 seconds

Top, right: 17–55mm lens at 28mm, f/22 for 1/8 sec.

Recently, Nikon announced its all-new, professional digital camera, the D2X. Of the camera’s many new changes (not the least of which is the quantum leap from 5.75 to 12.4 megapixels), I was quick to embrace its ability to record multiple exposures. The advent of the D2X will no doubt push other digital SLR camera manufacturers to include a multiple-exposure feature on their new releases, as well. However, if your current camera doesn’t offer this feature—and you don’t want to wait until you get a camera that does—you can duplicate the same effect right in Photoshop, albeit over the course of about twenty minutes versus the less than one minute it takes to do it in camera with the Nikon D2X. And, there are a couple of ways to do it, too.

First thing is to head out and find a suitable subject—most any landscape that fills the frame and allows for only a little, if any, sky works the best. Take eight different shots of your scene, varying your composition ever so slightly up or down or side to side. After shooting all eight images, you must create one layer for each in Photoshop and then change the opacity level of each image to 12.5 percent (12.5 × 8 = 100 percent). After you’ve done all the layers, choose Flatten Image from the Layer pulldown menu and you’ll have a multiple exposure.

Your other option is to shoot at an exposure for all eight images as if you had a camera that offered the multiple-exposure feature. It’s a simple mathematical calculation that goes like this: Start with the aperture set to f/16 and then adjust the shutter speed until a correct exposure is indicated. Let’s say at f/16 the correct exposure for one image is 1/60 sec. Then if you’re sandwiching two images together, you’d need to shoot both images at 1/125 sec. (1/125 + 1/125 = 2/125 or 1/60). So following this, if you’re sandwiching four images, each would need to be exposed at 1/250 sec., and if you’re sandwiching eight images, each would need 1/500 sec. So, that’s the combination you’d use: All eight of your images would be shot at f/16 for 1/500 sec. Once again, you would shoot each of these exposures at a slightly different angle, up or down or side to side. Or, you can also shoot each image at a different focal length, in effect zooming the camera with each exposure. (Keep in mind that each single exposures at f/16 for 1/500 sec. will be quite dark, so don’t be shocked when you download them onto the computer. Also, be forewarned that some digital cameras record noisy exposures when underexposed.)

After you return to the computer, open all eight images and choose one as the Background Layer image. Then, holding the shift key, drag all the other images onto this Background image. Seven new layers will automatically be created atop the background image. Set the blending mode of each layer to Screen (from the Layers palette or under Layer Style>Blending Options>Blend Mode in the Layers pulldown menu) and then choose Flatten Image (again from the Layers pulldown menu). Now you’re ready to make any color and contrast adjustments you deem necessary before you print out your image.

Handholding my camera and 17–55mm lens while shooting down into my neighbor’s petunia bed would have produced a very ordinary shot. But taking eight exposures, each at different focal lengths, and combining them in Photoshop resulted in a more interesting composition. I know of several photographers who are making a career of producing this kind of “fine art” photography.

Keystoning is the term used to describe the “Leaning Tower of Pisa” effect of converging lines in photographs of architectural subjects. It’s a very common result when shooting cityscapes with a wide-angle lens. Short of buying a two thousand dollar perspective-control lens, there really isn’t any way to avoid these slightly distorted, converging lines. But, within reason, Photoshop can oftentimes straighten those buildings for you, correcting this perspective problem in a matter of seconds.

Open your image in Photoshop, select the Crop tool from the toolbox, and drag the cursor from the top left corner to the bottom right corner and release. You will see the “marching ants” around the entire image. Go to the lower menu bar at the top of the screen and check the small box next to Perspective. Now, using the cursor, drag the top left corner of the marching ant border into the image so that the border is parallel to the tilting structure in the image. Do the same thing on the right side of the image. Then, double click in the image just to the right or left of the small center circle that appears on the image. Photoshop adjusts the image so that any tilting lines appear truly vertical, as they do when the human eye views the actual scene.

“Marching ant” border is dragged inward to run parallel to leaning buildings.

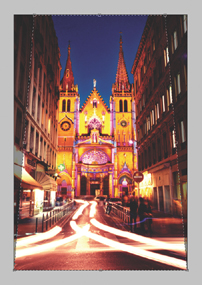

The Lumière Festival in Lyon, France, takes place every December 8 and lasts for four days. Every single monument, church, and statue of any note is illuminated via a laser show and the Church of St. Nezier is no exception. The show starts right at dusk, and with so many monuments lit up at once, it’s difficult to photograph several of the displays before the dusky blue sky has turned black. Finding a clear shot is also a challenge as the streets are crawling with photographers, amateurs and professionals alike, so it’s best to head out about 45 minutes before the show begins and stake your claim early—of course, with tripod in hand!

12–24mm lens at 20mm, f/16 for 8 seconds

What exactly is a panorama photo? It’s a composition that extends to the left and right—far beyond the widest reaches of most wide-angle lenses—without any signs of distortion. Who doesn’t like a great panoramic landscape? I have yet to meet anyone who doesn’t. Kodak and Fuji both figured that out, too, so some year ago they introduced their panorama disposal cameras. Although these are not true panorama cameras, they generate a panoramic-like picture format that makes us think they are. In fact, these disposable panoramic cameras are nothing more than cameras with a moderately wide-angle lens and an exposure window designed to crop the normal 35mm film into a panoramic format, cutting off about one quarter of both the top and bottom of the 35mm negative. But what the heck, I liked these cameras enough to have brought several along on a few family outings some years ago. I just couldn’t resist the look of those oversized, very long color prints.

But truth be told, to actually go out and shoot a real panorama image, you need to use a true panorama camera—and, of course, a true panorama camera is not cheap. I’ve owned the Fuji 6X17 Panorama and also the Hasselblad 6X12, both costing several thousands of dollars, and have never been disappointed with the results. For most of us, however, the cost is hard to justify. And until recently, if you wanted to record that sweeping landscape without distortion, your only option was to buy that panorama camera. But now, once again, Photoshop comes to the rescue with its ability to make panoramic images—without the panorama camera itself! It’s a technique called photo-stitching. (Photoshop doesn’t have the corner on this market, by the way; there are many other photo-stitching software programs available, but since my Photoshop CS already includes the photo-stitching feature, I see no reason to buy another program.)

Although panoramas are associated with wide, sweeping visions, don’t limit yourself to shooting them with only a wide-angle lens. You can just as easily use a normal or moderate telephoto lens—you’ll just have to shoot more exposures. Let me explain the photo-stitching process.

Rule number one when photo-stitching panoramas is the absolute need for a tripod. And, as elementary as this sounds, you will also need to choose a subject worthy of panoramic treatment (although panoramic images often exude strong responses, not everything is deserving of panoramic treatment). When you look out upon a scene before you, establish where your composition will begin and end—not from front to back (as we normally think of things) but from side to side. Next, don’t tighten down the horizontal pivot of your tripod; you’ll need to be able to turn the camera freely from side to side.

Rule number two is that the camera be as level as possible. You can buy levels that attach to your camera’s hot shoe if you really want to be sure it’s level, and you can then test how level it is by first rotating the camera through the entire panorama scene without actually shooting. It also helps if you use manual exposure mode and set the exposure for each image that you intend to use in the stitching process. And finally, it’s best to use the same white balance setting throughout the sequence (so, if you have been looking for a reason to follow my suggestion of setting and leaving the WB on Cloudy, this is it).

Once all that’s done, begin by taking the first shot of either the far left or far right side of your composition. Then swivel the camera so that the composition now includes about 50 percent of the first composition and 50 percent of new, neighboring subject matter. Repeat this process until you have reached the other end of your panoramic composition.

To make the panorama, open all the images in Photoshop. Open up Levels in the Adjustment Menu, and tweak each one, if needed, so that they are of like value, but don’t change the white balance, hue, saturation, cropping, or sharpness. Either save them all to the desktop or put them in a folder. Select Automate from the File pulldown menu, and click on Photomerge. In the window that opens, indicate which images or folder to use, click OK, and in a manner of seconds, Photomerge “stitches” the images together into a panorama. At this point, you can adjust color, contrast, and cropping.

The panoramic format seems the logical choice when shooting any mountain range, since these ranges can seem to go on forever. This shot (from a field above the town of Cordon, France) is a true panorama that I made with my Fuji 6X17 (120mm film format) and 105mm lens on tripod. I used a classic storytelling aperture and set my focus to five feet. The film was Fuji Velvia ISO 50.

105mm lens, f/32 for 1/30 sec.

I used Photoshop’s Photomerge feature to combine three separate shots of San Diego into this panoramic image. I metered off the dusky blue sky, then recomposed and shot the three photos, moving from right to left and making certain that the second and third exposures included about a third of the previous frame. I did make a few fine-tuning adjustments (with Levels, Hue/Saturation, and Unsharp Mask) before applying Photomerge to get the final, “stitched-together” panorama. And, although the wait was “long” (five minutes from start to finish) compared to the half a second it would have taken to make this with the Fuji 6X17, I can’t help but smile knowing that I didn’t spend over two thousand dollars to get it.

17–55mm lens at 45mm, f/11 for 1/2 sec.

My youngest daughter, Sophie, enjoys posing for the camera, unlike her mother and sister, who often “dread it.” She also likes to “act,” so it was an easy proposition when I asked her to be part of this panorama idea. The creative possibilities are truly endless if you think of the Photoshop panorama as a movie unfolding. With every frame, you can show another part of your plot as it progresses, and then stitch them together to make an uninterrupted panoramic story.

One possibility, for example, could be to have your subject change outfits from one frame to the next, while the background remains the same throughout. Another idea for the real adventurous (and with the appropriate model, of course) could be to start with a fully clothed model who becomes progressively less clothed and finishes as a nude.

In Sophie’s case, she wanted to have fun with different expressions, so we simply planned accordingly.

17–55mm lens at 22mm, 1/60 sec.

AVOID SIDELIT SUBJECTS FOR PHOTO-STITCHING

When using Photoshop to stitch together a panorama, you should try to avoid shooting sidelit scenes since most of them often require the use of a polarizing filter. As you move the camera for each shot, the polarizing effect can become either more or less intense in the sky, and this will show up in the overall panorama as a glaring gaffe. As you try out this Photomerge feature, at least in the beginning, shoot only frontlit scenes so that your confidence doesn’t get broken in your first few attempts. As you become more familiar with the panorama process, you can take on more challenging subjects and lighting situations—including the ultimate challenge: a backlit sunset sky with a lone tree on the horizon.

After putting a great deal of thought and technical know-how into creating an image, there’s nothing more frustrating than realizing that you still didn’t get close enough to fill the frame, or that you didn’t see the obvious vertical shot, or that you didn’t notice the crooked horizon line. Not a problem, as you discover the ease with which you can crop your image in any number of software imaging programs, Photoshop included. In Photoshop, simply use the Crop tool, and just like that you can cut out distracting stuff on the left and right of your image, or you can crop in really tight to make that vertical composition you wanted, or you can straighten that horizon line.

However, this ease of cropping with software programs is, no doubt, in part behind many photographers’ lackadaisical attitude toward getting effective compositions in camera. These photographers reason, What the heck, I’ll just crop it later on the computer.

And there’s another downside. Despite how thrilled you might be with the results of your crop on the computer screen, cropping into any image has a price: more noise and a loss of sharpness. And, when you crop out more than 10 to 20 percent, that price becomes more evident.

Let’s assume that the original photo was produced with a 6 megapixel camera. The output size of that file—whether it be raw, TIFF, or JPEG FINE—will be around 2048 × 3000 ppi (pixels per inch) or, in more familiar terms, a print size of about 6.8 × 10.2 inches. When you crop 10 to 20 percent of the image, you are in effect casting aside 10 to 20 percent of the pixels. And, assuming you still want to produce an 8 × 10-inch print, you’re now requiring that fewer pixels cover the same 8 × 10-inch area. You’re asking the Pixel family to make unreasonable stretches. But stretch they do, and in the end, you will have the results to prove it: Both grain (noise) and a loss of sharpness become evident, and the photograph appears flawed.

There are a number of software programs available to combat these kinds of problems, one of the most popular being Genuine Fractals. This acts as an “instant muscle-building” program. In effect, the remaining Pixel family, all 4,800,000 strong using the previous example, can now pull the same weight of the original 6,000,000 members without so much as a loss in the print quality. But again, this additional software costs money, and then there’s the time it takes to do the crop on the computer. Again, just another great reason to strive to make all of your compositional arrangements a success in camera!

Here is the classic shot of Mom and the kids on their winter ski vacation (left). It might look familiar if, like so many other shooters, you don’t pay attention to what’s in your viewfinder. The two huge problems? The subjects are too far away and the entire image is crooked. If you wait to correct it in Photoshop, you’ll be disappointed. After cropping in closer and straightening, you won’t be able to generate a print larger than 5 × 7 inches because you will have cropped out too many pixels. This is why you should slow down and really—and I mean really—take a close look at what’s going on in the viewfinder before you press the shutter. Ask yourself if things are straight and if you are as close as you can be for the type of composition you want. If, after taking the shot and checking the LCD, you’re still not satisfied, try again. It doesn’t cost a single penny; the “film” is free, remember?

When it comes to preparing images for the World Wide Web, there is one rule or standard: Most everything on the Web is in JPEG format. And since you have been convinced to shoot everything in raw format, you may be wondering how to get a JPEG copy of those raw images that you want to send to friends or post to a family or professional Web site. It’s actually very easy—and made even easier when you set up an Action in Photoshop.

To create a single JPEG image, simply open up the file, go to Image Size in the Image pulldown menu, set the Resolution to 72 and then in the Pixel Dimensions box you will see Width and Height. If it’s a horizontal image, type 700 in the width window. If it’s a vertical image, type 700 in the height window. Also, make certain that all three boxes in the bottom of this window—Scale Styles, Constrain Proportions, and Resample Image—are checked. (This should already be done for you since these are checked by default in Photoshop, but maybe the kids found their way to the computer while you were out and.…) Now click OK, return to the File pulldown menu, and choose Save As. In the new dialog box that appears, click on Format. Choose JPEG, hit Save, and in the JPEG Options dialog box that opens, set the Quality slider to Maximum and click OK. The image is now ready for the World Wide Web.

To convert a whole batch of images to JPEGs, create an action from the procedure for converting a single image. Then you only have to manually convert the first image in the batch, and all the others that follow will be done automatically. How do you make an Action? First, organize all the images you want to convert to Web-ready JPEGs into one folder. Then, go to Actions in the Window pulldown menu. The Actions palette appears on the right side of your screen. Click on the small icon at the bottom of this palette that looks like a piece of paper with one corner turned up (the Create New Action button). A New Action window opens up and prompts you to name your action; type one in the Name field (for example, Web-Ready Images) and click the Record button (it’s the only round one at the bottom).

Now, open the folder that has all the images you want to convert to JPEGs. Once they are all open, you must manually convert the first one using the same steps mentioned for the single-image procedure. As you do this, the Actions palette records every step. After the first one is done, click on the Stop Record button (the square one at far left). You are now ready to Automate all of the other images in that folder. Simply click on the Play Selection button (it’s the sideways triangle next to the Record button). When you do this, every image in that folder is automatically converted to the same specifications as the first one; even if you are converting both horizontal and vertical compositions, the same measurement of 700 dpi will be applied to the “long” end (the longer dimension) of the image, whether that is the horizontal or the vertical axis. Pretty cool, huh?

The Actions feature also saves the Actions you create; so when you have a new folder of images you want to convert to Web-ready JPEGs, you can go to the Actions palette and find your previous action (Web-Ready Images, in our example). You merely click on this and the automated process starts up all over again. Nothing could be easier!

To figure out the largest print size (in inches) your digital camera can generate while still maintaining the highest quality, divide your camera’s vertical and horizontal pixel counts (found in the owner’s manual) by 200. For example, the pixel count of my Nikon D2X is 4288 × 2848. So, divided by 200, I get a maximum print size of roughly 21 × 14 inches.

So, what are we supposed to do with all of these digital files? I, personally, have no hard and fast rules for managing and storing my images except one: Make backup copies of everything! I was amazed to discover in a recent column written by John Owens at Popular Photography and Digital Magazine that 74 percent of digital shooters use the computer’s internal hard drive to store their images! Yikes! In case you haven’t heard, computer hard drives crash, and although not as often, even a Mac will crash. When a hard drive crashes, more often than not, everything is lost.

Here’s how I basically operate: My current workhorse for all of my digital workflow is a Mac G5 with dual 1.8 GHz processors, a 250 GB internal hard drive, 2 GBs of RAM, a LaCie 8X external DVD burner, and three LaCie 400 GB external hard drives. In addition, when I’m on the road, I pack my 15.2-inch Macintosh PowerBook with 1.5 GHz processor, 100 GB internal hard drive, 1 GB of RAM, a LaCie 8X external DVD burner, and a LaCie 250 GB external hard drive. Both machines are, of course, loaded with Photoshop CS2.

I shoot everything in raw format and always with a 2 GB or 4 GB compact flash card. On average, a one-day commercial shoot will usually generate 8 to 10 GBs of images. In the raw format, that’s about 400 to 500 images with my Nikon D2X. Keep in mind that most commercial shoots involve downloading images to the computer several times during the day for on-the-spot viewing by the client. If I’m out on a given day strictly shooting stock photography, I may end up shooting even more images if it’s a production shoot (one that involves models) or less if I’m simply shooting “catch as catch can.”

Once I’ve attached the compact flash card to the computer via a USB card reader, I’m able to copy all my images and download them into a folder on the computer’s desktop. I give this folder a brief name and always a date, for example Shipyards-Charlotte NC-07-15-04. I then open this same folder via Photoshop CS and can do an even tighter picture edit. I move any images that don’t make the grade to the trash, which then leaves me with my keepers, still in their raw state, of course. I then create two sets of color contact sheets of the keepers. Most photo-imaging programs can generate contact sheets, and with most software, including Photoshop CS, the design and layout of the sheets is automated.