VII.1 CONTEMPLATION OF FEELINGS

The Pāli term for “feeling” is vedanā, derived from the verb vedeti, which means both “to feel” and “to know”.1 In its usage in the discourses, vedanā comprises both bodily and mental feelings.2 Vedanā does not include “emotion” in its range of meaning.3 Although emotions arise depending on the initial input provided by feeling, they are more complex mental phenomena than bare feeling itself and are therefore rather the domain of the next satipaṭṭhāna, contemplation of states of mind.

The satipaṭṭhāna instructions for contemplation of feelings are:

When feeling a pleasant feeling, he knows “I feel a pleasant feeling”; when feeling an unpleasant feeling, he knows “I feel an unpleasant feeling”; when feeling a neutral feeling, he knows “I feel a neutral feeling.” When feeling a worldly pleasant feeling, he knows “I feel a worldly pleasant feeling”; when feeling an unworldly pleasant feeling, he knows “I feel an unworldly pleasant feeling”; when feeling a worldly unpleasant feeling, he knows “I feel a worldly unpleasant feeling”; when feeling an unworldly unpleasant feeling, he knows “I feel an unworldly unpleasant feeling”; when feeling a worldly neutral feeling, he knows “I feel a worldly neutral feeling”; when feeling an unworldly neutral feeling, he knows “I feel an unworldly neutral feeling”.4

The first part of the above instructions distinguishes between three basic kinds of feelings: pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral. According to the discourses, developing understanding and detachment in regard to these three feelings has the potential to lead to freedom from dukkha.5 Since such understanding can be gained through the practice of satipaṭṭhāna,6 contemplation of feelings is a meditation practice of considerable potential. This potential is based on the simple but ingenious method of directing awareness to the very first stages of the arising of likes and dislikes, by clearly noting whether the present moment’s experience is felt as “pleasant”, or “unpleasant”, or neither.

Thus to contemplate feelings means quite literally to know how one feels, and this with such immediacy that the light of awareness is present before the onset of reactions, projections, or justifications in regard to how one feels. Undertaken in this way, contemplation of feelings will reveal the surprising degree to which one’s attitudes and reactions are based on this initial affective input provided by feelings.

The systematic development of such immediate knowing will also strengthen one’s more intuitive modes of apperception, in the sense of the ability to get a feel for a situation or another person. This ability offers a helpful additional source of information in everyday life, complementing the information gained through more rational modes of observation and consideration.

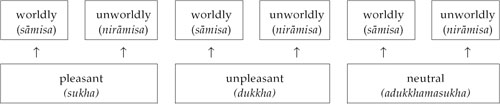

In the satipaṭṭhāna instructions, mindfulness of these three feelings is followed by directing awareness to an additional subdivision of feelings into “worldly” (sāmisa) and “unworldly” (nirāmisa).7 According to a passage in the Aṅguttara Nikāya, this sixfold classification represents the range of diversity of feelings.8 Thus with this sixfold scheme, contemplation of feeling comprehensively surveys the whole scale of diversity of the phenomenon “feeling” (cf. Fig. 7.1 overleaf).

The distinction between worldly (sāmisa) and unworldly (nirāmisa) feelings is concerned with the difference between feelings related to the “flesh” (āmisa) and feelings related to renunciation.9 This additional dimension revolves around an evaluation of feeling that is based not on its affective nature, but on the ethical context of its arising. The basic point introduced here is awareness of whether a particular feeling is related to progress or regress on the path.

Unlike his ascetic contemporaries, the Buddha did not categorically reject all pleasant feelings, nor did he categorically recommend unpleasant experiences for their supposedly purifying effect. Instead, he placed emphasis on the mental and ethical consequences of all types of feeling. With the help of the above sixfold classification, this ethical dimension becomes apparent, uncovering in particular the relation of feelings to the activation of a latent mental tendency (anusaya) towards lust, irritation, or ignorance.10 As the Cūḷavedalla Sutta points out, the arising of these underlying tendencies is mainly related to the three worldly types of feelings, whereas unworldly pleasant or neutral feelings arising during deep concentration, or unworldly unpleasant feelings arising owing to dissatisfaction with one’s spiritual imperfection, do not stimulate these underlying tendencies.11

The conditional relation between feelings and such mental tendencies is of central importance, since by activating these latent tendencies, feelings can lead to the arising of unwholesome mental reactions. The same principle underlies the corresponding section of the twelve links of dependent co-arising (paṭicca samuppāda), where feelings form the condition that can lead to the arising of craving (taṇhā).12

This crucially important conditional dependence of craving and mental reactions on feeling probably constitutes the central reason why feelings have become one of the four satipaṭṭhānas. In addition, the arising of pleasant or unpleasant feelings is fairly easy to notice, which makes feelings convenient objects of meditation.13

A prominent characteristic of feelings is their ephemeral nature. Sustained contemplation of this ephemeral and impermanent nature of feelings can then become a powerful tool for developing disenchantment with them.14 A detached attitude towards feelings, owing to awareness of their impermanent nature, is characteristic of the experiences of an arahant.15

Another aspect inviting contemplation is the fact that the affective tone of any feeling depends on the type of contact that has caused its arising.16 Once this conditioned nature of feelings is fully apprehended, detachment arises naturally and one’s identification with feelings starts to dissolve.

A poetic passage in the Vedanā Saṃyutta compares the nature of feelings to winds in the sky coming from different directions.17 Winds may be sometimes warm and sometimes cold, sometimes wet and sometimes dusty. Similarly, in this body different types of feelings arise. Sometimes they are pleasant, sometimes neutral, and sometimes unpleasant. Just as it would be foolish to contend with the vicissitudes of the weather, one need not contend with the vicissitudes of feelings. Contemplating in this way, one becomes able to establish a growing degree of inner detachment with regard to feelings. A mindful observer of feelings, by the very fact of observation, no longer fully identifies with them and thereby begins to move beyond the conditioning and controlling power of the pleasure–pain dichotomy.18 The task of undermining identification with feelings is also reflected in the commentaries, which point out that to inquire “who feels?” is what leads from merely experiencing feeling to contemplating them as a satipaṭṭhāna.19

For the sake of providing some additional information about the importance and relevance of contemplation of feelings, I will now briefly consider the relation of feelings to the forming of views (diṭṭhi) and opinions, and examine in more detail the three types of feelings presented in the satipaṭṭhāna instructions.

VII.2 FEELINGS AND VIEWS (DIṬṬHI)

The cultivation of a detached attitude towards feelings is the introductory theme of the Brahmajāla Sutta. At the outset of this discourse, the Buddha instructed his monks to be neither elated by praise nor displeased by blame, since either reaction would only upset their mental composure. Next, he comprehensively surveyed the epistemological grounds underlying the different views prevalent among ancient Indian philosophers and ascetics. By way of conclusion to this survey he pointed out that, having fully understood feelings, he had gone beyond all these views.20

The intriguing feature of the Buddha’s approach is that his analysis focused mainly on the psychological underpinnings of views, rather than on their content.21 Because of this approach, he was able to trace the arising of views to craving (taṇhā), which in turn arises dependent on feeling.22 Conversely, by fully understanding the role of feeling as a link between contact and craving, the view-forming process itself can be transcended.23 The Pāsādika Sutta explicitly presents such transcendence of views as an aim of satipaṭṭhāna contemplation.24 Thus the second satipaṭṭhāna, contemplation of feelings, has an intriguing potential to generate insight into the genesis of views and opinions.

Sustained contemplation will reveal the fact that feelings decisively influence and colour subsequent thoughts and reactions.25 In view of this conditioning role of feeling, the supposed supremacy of rational thought over feelings and emotions turns out to be an illusion.26 Logic and thought often serve merely to rationalize already existing likes and dislikes, which in turn are conditioned by the arising of either pleasant or unpleasant feelings.27 The initial stages of the perceptual process, when the first traces of liking and disliking appear, are usually not fully conscious, and their decisive influence on subsequent evaluations often passes undetected.28

Considered from a psychological perspective, feeling provides quick feedback during information processing, as a basis for motivation and action.29 In the early history of human evolution, such rapid feedback evolved as a mechanism for surviving dangerous situations, when a split-second decision between flight or fight had to be made. Such decisions are based on the evaluative influence of the first few moments of perceptual appraisal, during which feeling plays a prominent role. Outside such dangerous situations, however, in the comparatively safe average living situation in the modern world, this survival function of feelings can sometimes produce inadequate and inappropriate reactions.

Contemplation of feelings offers an opportunity to bring these evaluative and conditioning functions back into conscious awareness. Clear awareness of the conditioning impact of feeling can lead to a restructuring of habitual reaction patterns that have become meaningless or even detrimental. In this way, emotions can be deconditioned at their point of origin.30 Without such deconditioning, any affective bias, being the outcome of the initial evaluation triggered by feeling, can find its expression in apparently well-reasoned “objective” opinions and views. In contrast, a realistic appraisal of the conditional dependence of views and opinions on the initial evaluative input provided by feeling uncovers the affective attachment underlying personal views and opinions. This dependency of views and opinions on the first evaluative impact of feeling is a prominent cause of subsequent dogmatic adherence and clinging.31

In ancient India, the Buddha’s analytical approach to views formed a striking contrast to the prevalent philosophical speculations. He dealt with views by examining their affective underpinnings. For the Buddha, the crucial issue was to uncover the psychological attitude underlying the holding of any view,32 since he clearly saw that holding a particular view is often a manifestation of desire and attachment.

An important aspect of the early Buddhist conception of right view is therefore to have the “right” attitude towards one’s beliefs and views. The crucial question here is whether one has developed attachment and clinging to one’s own views,33 which often manifests in heated arguments and disputation.34 The more right view can be kept free from attachment and clinging, the better it can unfold its full potential as a pragmatic tool for progress on the path.35 That is, right view as such is never to be given up; in fact, it constitutes the culmination of the path. What is to be given up is any attachment or clinging in regard to it.

In the context of actual meditation practice, the presence of right view finds its expression in a growing degree of detachment and disenchantment with conditioned phenomena, owing to a deepening realization of the truth of dukkha, its cause, its cessation, and the way leading to its cessation. Such detachment is also reflected in the absence of “desires and discontent”, stipulated in the satipaṭṭhāna “definition”, and in the instruction to avoid “clinging to anything in the world”, mentioned in the satipaṭṭhāna “refrain”.

VII.3 PLEASANT FEELING AND THE IMPORTANCE OF JOY

The conditioning role of pleasant feelings in leading to likes and eventually to dogmatic attachment has some far-reaching implications. But this does not mean that all pleasant feelings have simply to be avoided. In fact, the realization that pleasant feelings are not simply to be shunned was a direct outcome of the Buddha’s own quest for liberation.

On the eve of his awakening, the Buddha had exhausted the traditional approaches to realization, without gaining awakening.36 While recollecting his past experiences and considering what approach might constitute an alternative, he remembered a time in his early youth when he experienced deep concentration and pleasure, having attained the first absorption (jhāna).37 Reflecting further on this experience, he came to the conclusion that the type of pleasure experienced then was not unwholesome, and therefore not an obstacle to progress.38 The realization that the pleasure of absorption constitutes a wholesome and advisable type of pleasant feeling marked a decisive turning point in his quest. Based on this crucial understanding, the Buddha was soon able to break through to awakening, which earlier, in spite of considerable concentrative attainments and a variety of ascetic practices, he had been unable to achieve.

After his awakening, the Buddha declared himself to be one who lived in happiness.39 This statement clearly shows that, unlike some of his ascetic contemporaries, the Buddha was no longer afraid of pleasant feelings. As he pointed out, it was precisely the successful eradication of all mental unwholesomeness that caused his happiness and delight.40 In a similar vein, the verses composed by awakened monks and nuns often extol the happiness of freedom gained through the successful practice of the path.41 The presence of delight and non-sensual joy among the awakened disciples of the Buddha often found its expression in poetic descriptions of natural beauty.42 Indeed, the early Buddhist monks delighted in their way of life, as testified by a visiting king who described them as “smiling and cheerful, sincerely joyful and plainly delighting, living at ease and unruffled”.43 This description forms part of a comparison made by the king between the followers of the Buddha and other ascetics, whose demeanour was comparatively gloomy. To him, the degree of joy exhibited by the Buddha’s disciples corroborated the appropriateness of the Buddha’s teaching. These passages document the significant role of non-sensual joy in the life of the early Buddhist monastic community.

The skilful development of non-sensual joy and happiness was an outcome of the Buddha’s first-hand realization, which had shown him the need to differentiate between wholesome and unwholesome types of pleasure.44 The satipaṭṭhāna instructions for contemplating feelings reflect this wisdom by distinguishing between worldly and unworldly types of pleasant feelings.

The ingenuity of the Buddha’s approach was not only his ability to discriminate between forms of happiness and pleasure which are to be pursued and those which are to be avoided, but also his skilful harnessing of non-sensual pleasure for the progress along the path to realization. Numerous discourses describe the conditional dependence of wisdom and realization on the presence of non-sensual joy and happiness. According to these descriptions, based on the presence of delight (pāmojja), joy (pīti) and happiness (sukha) arise and lead in a causal sequence to concentration and realization. One discourse compares the dynamics of this causal sequence to the natural course of rain falling on a hilltop, gradually filling the streams and rivers, and finally flowing down to the sea.45 Once non-sensual joy and happiness have arisen, their presence will lead naturally to concentration and realization.46 Conversely, without gladdening the mind when it needs to be gladdened, realization will not be possible.47

The importance of developing non-sensual joy is also reflected in the Araṇavibhaṅga Sutta, where the Buddha encouraged his disciples to find out what really constitutes true happiness and, based on this understanding, to pursue it.48 This passage refers in particular to the experience of absorption, which yields a form of happiness that far surpasses its worldly counterparts.49 Alternatively, non-sensual pleasure can also arise in the context of insight meditation.50

A close examination of the Kandaraka Sutta brings to light a progressive refinement of non-sensual happiness taking place during the successive stages of the gradual training. The first levels of this ascending series are the forms of happiness that arise owing to blamelessness and contentment. These in turn lead to the different levels of happiness gained through deep concentration. The culmination of the series comes with the supreme happiness of complete freedom through realization.51

The important role of non-sensual joy is also reflected in the Abhidhammic survey of states of mind. Out of the entire scheme of one-hundred-and-twenty-one states of mind, the majority are accompanied by mental joy, while only three are associated with mental displeasure.52 This suggests that the Abhidhamma places great emphasis on the role and importance of joy.53 The Abhidhammic scheme of states of mind has moreover kept a special place for the smile of an arahant.54 Somewhat surprisingly, it occurs among a set of so-called “rootless” (ahetu) and “inoperative” (akiriya) states of mind. These states of mind are neither “rooted” in wholesome or unwholesome qualities, nor related to the “operation” of karma. Out of this particular group of states of mind, only one is accompanied by joy (somanassahagatā): the smile of the arahant. The unique quality of this smile was apparently sufficient ground for the Abhidhamma to allot it a special place within its scheme.

Extrapolating from the above, the entire scheme of the gradual training can be envisaged as a progressive refinement of joy. To balance out this picture, it should be added that progress along the path invariably involves unpleasant experiences as well. However, just as the Buddha did not recommend the avoidance of all pleasant feelings, but emphasized their wise understanding and intelligent use, so his position regarding unpleasant feelings and experiences was clearly oriented towards the development of wisdom.

In the historical context of ancient India, the wise analysis of feeling proposed by the Buddha constituted a middle path between the worldly pursuit of sensual pleasures and ascetic practices of penance and self-mortification. A prominent rationale behind the self-mortifications prevalent among ascetics at that time was an absolutist conception of karma. Self-inflicted pain, it was believed, brings an immediate experience of the accumulated negative karmic retribution from the past, and thereby accelerates its eradication.55

The Buddha disagreed with such mechanistic theories of karma. In fact, any attempt to work through the retribution of the entire sum of one’s past unwholesome deeds is bound to fail, because the series of past lives of any individual is without a discernible beginning,56 so the amount of karmic retribution to be exhausted is unfathomable. Besides, painful feelings can arise from a variety of other causes.57

Although karmic retribution cannot be avoided and will quite probably manifest in one form or another during one’s practice of the path,58 awakening is not simply the outcome of mechanically eradicating the accumulated effects of past deeds. What awakening requires is the eradication of ignorance (avijjā) through the development of wisdom.59 With the complete penetration of ignorance through insight, arahants go beyond the range of most of their accumulated karmic deeds, apart from those still due to ripen in this present lifetime.60

The Buddha himself, prior to his own awakening, had also taken for granted that painful experiences have purifying effects.61 After abandoning ascetic practices and gaining realization, he knew better. The Cūḷadukkhakkhandha Sutta reports the Buddha’s attempt to convince some of his ascetic contemporaries of the fruitlessness of self-inflicted suffering. The discussion ended with the Buddha making the ironic point that, in contrast to the painful results of self-mortification, he was able to experience degrees of pleasure vastly superior even to those available to the king of the country.62 Clearly, for the Buddha, realization did not depend on merely enduring painful feelings.63 In fact, considered from the psychological viewpoint, intentional subjection to self-inflicted pain can be an expression of deflected aggression.64

The experience of unpleasant feelings can activate the latent tendency to irritation and lead to attempts to repress or avoid such unpleasant feelings. Moreover, aversion to pain can, according to the Buddha’s penetrating analysis, fuel the tendency to seek sensual gratification, since from the unawakened point of view the enjoyment of sensual pleasures appears to be the only escape from pain.65 This creates a vicious circle in which, with each experience of feeling, pleasant or unpleasant, the bondage to feeling increases.

The way out of this viscious circle lies in mindful and sober observation of unpleasant feelings. Such non-reactive awareness of pain is a simple but effective method for skilfully handling a painful experience. Simply observing physical pain for what it is prevents it from producing mental repercussions. Any mental reaction of fear or resistance to pain would only increase the degree of unpleasantness of the painful experience. An accomplished meditator might be able to experience solely the physical aspect of an unpleasant feeling without allowing mental reactions to arise. Thus meditative skill and insight have an intriguing potential for preventing physical sickness from affecting the mind.66

The discourses relate this ability of preventing physical pain from affecting mental composure to the practice of satipaṭṭhāna in particular.67 In this way, a wise observation of pain through satipaṭṭhāna can transform experiences of pain into occasions for deep insight.

While pleasant and unpleasant feelings can activate the respective latent tendencies to lust and irritation, neutral feelings can stimulate the latent tendency to ignorance.68 Ignorance in regard to neutral feelings is to be unaware of the arising and disappearance of neutral feelings, or not to understand the advantage, disadvantage, and escape in relation to neutral feelings.69 As the commentaries point out, awareness of neutral feelings is not an easy task and should best be approached by way of inference, by noting the absence of both pleasant and unpleasant feelings.70

Of further interest in a discussion of neutral feeling is the Abhidhammic analysis of feeling tones arising at the five physical sense doors. The Abhidhamma holds that only the sense of touch is accompanied by pain or pleasure, while feelings arising at the other four sense doors are invariably neutral.71 This Abhidhammic presentation offers an intriguing perspective on contemplation of feeling, since it invites an inquiry into the degree to which an experience of delight or displeasure in regard to sight, sound, smell, or taste is simply the outcome of one’s own mental evaluation.

In addition to this inquiry, a central feature to be contemplated in regard to neutral feelings is their impermanent nature.72 This is of particular importance because, in actual experience, neutral feeling appears easily to be the most stable of the three types of feeling. Thus to counteract the tendency to regard it as permanent, its impermanent nature need to be observed. Contemplated in this way, neutral feeling will lead to the arising of wisdom, thereby counteracting the latent tendency to ignorance.

The Saḷāyatanavibhaṅga Sutta points out that the difference between neutral feelings associated with ignorance and those associated with wisdom is related to whether such feelings transcend their object.73 In the deluded case, neutral feeling is predominantly the result of the bland features of the object, where the lack of effect on the observer results in the absence of pleasant or unpleasant feelings. Conversely, neutral feeling related to the presence of wisdom transcends the object, since it results from detachment and equanimity, and not from the pleasant or unpleasant features of the object.

According to the same discourse, the establishment of such equanimity is the result of a progressive refinement of feelings, during which at first the three types of feelings related to a life of renunciation are used to go beyond their more worldly and sensual counterparts.74 In the next stage, mental joy related to renunciation is used to confront and go beyond difficulties related to renunciation. This process of refinement then leads up to equanimous feelings, transcending even non-sensual feelings of mental joy. Equanimity and detachment as a culmination of practice also occur in the satipaṭṭhāna refrain for contemplation of feelings, which instructs the meditator to contemplate all kinds of feeling “free from dependencies” and “without clinging”.75