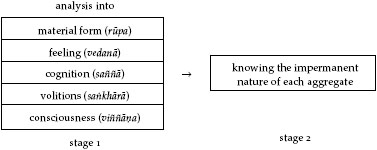

Fig. 10.1 Two stages in the contemplation of the five aggregates

The present satipaṭṭhāna exercise examines the five aggregates which constitute the basic components that make up “oneself”. The instructions are:

He knows “such is material form, such its arising, such its passing away; such is feeling, such its arising, such its passing away; such is cognition, such its arising, such its passing away; such are volitions, such their arising, such their passing away; such is consciousness, such its arising, such its passing away.”1

Underlying the above instructions are two stages of contemplation: clear recognition of the nature of each aggregate, followed in each case by awareness of its arising and passing away (cf. Fig. 10.1 below). I will first attempt to clarify the range of each aggregate. Then I will examine the Buddha’s teaching of anattā within its historical context, in order to investigate the way in which the scheme of the five aggregates can be used as an analysis of subjective experience. After that I will consider the second stage of practice, which is concerned with the impermanent and conditioned nature of the aggregates.

Clearly recognizing and understanding the five aggregates is of considerable importance, since without fully understanding them and developing detachment from them, it will not be possible to gain complete freedom from dukkha.2 Indeed, detachment and dispassion regarding these five aspects of subjective personality leads directly to realization.3 The discourses, and the verses composed by awakened monks and nuns, record numerous cases where a penetrative understanding of the true nature of the five aggregates culminated in full awakening.4 These instances highlight the outstanding potential of this particular satipaṭṭhāna contemplation.

These five aggregates are often referred to in the discourses as the “five aggregates of clinging” (pañcupādānakkhandha).5 In this context “aggregate” (khandha) is an umbrella term for all possible instances of each category, whether past, present, or future, internal or external, gross or subtle, inferior or superior, near or far.6 The qualification “clinging” (upādāna) refers to desire and attachment in regard to these aggregates.7 Such desire and attachment in relation to the aggregates is the root cause for the arising of dukkha.8

The sequence of these five aggregates leads from the gross physical body to increasingly subtle mental aspects.9 The first of the aggregates, material form (rūpa), is usually defined in the discourses in terms of the four elementary qualities of matter.10 A discourse in the Khandha Saṃyutta explains that material form (rūpa) refers to whatever is affected (ruppati) by external conditions such as cold and heat, hunger and thirst, mosquitoes and snakes, emphasizing the subjective experience of rūpa as a central aspect of this aggregate.11

Next in the sequence of the aggregates come feeling (vedanā) and cognition (saññā), which represent the affective and the cognitive aspects of experience.12 In the context of the process of perception, cognition (saññā) is closely related to the arising of feeling, both depending on stimulation through the six senses by way of contact (phassa).13 The standard presentations in the discourses relate feeling to the sense organ, but cognition to the respective sense object.14 This indicates that feelings are predominantly related to the subjective repercussions of an experience, while cognitions are more concerned with the features of the respective external object. That is, feelings provide the “how” and cognitions the “what” of experience.

To speak of a “cognition” of an object refers to the act of identifying raw sensory data with the help of concepts or labels, such as when one sees a coloured object and “re-cognizes” it as yellow, red, or white, etc.15 Cognition to some extent involves the faculty of memory, which furnishes the conceptual labels used for recognition.16

The fourth aggregate comprises volitions (saṅkhārā), representing the conative aspect of the mind.17 These volitions or intentions correspond to the reactive or purposive aspect of the mind, that which reacts to things or their potentiality.18 The aggregate of volitions and intentions interacts with each of the aggregates and has a conditioning effect upon them.19 In the subsequent developments of Buddhist philosophy, the meaning of this term expanded until it came to include a wide range of mental factors.20

The fifth aggregate is consciousness (viññāṇa). Although at times the discourses use “consciousness” to represent mind in general,21 in the context of the aggregate classification it refers to being conscious of something.22 This act of being conscious is most prominently responsible for providing a sense of subjective cohesiveness, for the notion of a substantial “I” behind experience.23 Consciousness depends on the various features of experience supplied by name-and-form (nāmarūpa), just as name-and-form in turn depend on consciousness as their point of reference.24 This conditional interrelationship creates the world of experience, with consciousness being aware of phenomena that are being modified and presented to it by way of name-and-form.25

To provide a practical illustration of the five aggregates: during the present act of reading, for example, consciousness is aware of each word through the physical sense door of the eye. Cognition understands the meaning of each word, while feelings are responsible for the affective mood: whether one feels positive, negative, or neutral about this particular piece of information. Because of volition one either reads on, or stops to consider a passage in more depth, or even refers to a footnote.

The discourses describe the characteristic features of these five aggregates with a set of similes. These compare material form to the insubstantial nature of a lump of foam carried away by a river; feelings to the impermanent bubbles that form on the surface of water during rain; cognition to the illusory nature of a mirage; volitions to the essenceless nature of a plantain tree (because it has no heartwood); and consciousness to the deceptive performance of a magician.26

This set of similes points to central characteristics that need to be understood with regard to each aggregate. In the case of material form, contemplating its unattractive and insubstantial nature corrects mistaken notions of substantiality and beauty. Concerning feelings, awareness of their impermanent nature counteracts the tendency to search for pleasure through feelings. With regard to cognition, awareness of its deluding activity uncovers the tendency to project one’s own value judgements onto external phenomena as if these were qualities of the outside objects. With volitions, insight into their selfless nature corrects the mistaken notion that willpower is the expression of a substantial self. Regarding consciousness, understanding its deceptive performance counterbalances the sense of cohesiveness and substantiality it tends to give to what in reality is a patchwork of impermanent and conditioned phenomena.

Owing to the influence of ignorance, these five aggregates are experienced as embodiments of the notion “I am”. From the unawakened point of view, the material body is “Where I am”, feelings are “How I am”, cognitions are “What I am” (perceiving), volitions are “Why I am” (acting), and consciousness is “Whereby I am” (experiencing). In this way, each aggregate offers its own contribution to enacting the reassuring illusion that “I am”.

By laying bare these five facets of the notion “I am”, this analysis of subjective personality into aggregates singles out the component parts of the misleading assumption that an independent and unchanging agent inheres in human existence, thereby making possible the arising of insight into the ultimately selfless (anattā) nature of all aspects of experience.27

In order to assess the implications of the aggregate scheme, a brief examination of the teaching of anattā against the background of the philosophical positions in existence in ancient India will be helpful at this point.

X.2 THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF THE TEACHING ON ANATTĀ

At the time of the Buddha, a variety of differing views about the nature of the self existed. The Ājīvika teachings, for example, proposed a soul having a particular colour and considerable size as the true self.28 The Jains posited a finite soul, similarly possessed of size and weight.29 According to them, the soul survived physical death, and in its pure state it possessed infinite knowledge.30 The Upaniṣads proposed an eternal self (ātman), unaffected by the vicissitudes of change. Upaniṣadic conceptions about such an eternal self ranged from a physical self the size of a thumb abiding in the heart area and leaving the body during sleep, to an unobservable and unknowable self, immaterial, free from death and sorrow, beyond any worldly distinction between subject and object.31 In the Upaniṣadic analysis of subjective experience, this eternal self, autonomous, permanent, and blissful, was taken to be the agent behind all the senses and activities.32

The materialist schools, on the other hand, rejected all immaterial conceptions of a self or soul. In order to account for causality, they proposed a theory based on the inherent nature (svabhāva) of material phenomena.33 According to them, a human individual was just an automaton functioning according to the dictates of matter. From their perspective, human effort was of no avail and there was no such thing as ethical responsibility.34

In this context, the Buddha’s position cuts a middle path between the belief in an eternal soul and the denial of anything beyond mere matter. By affirming karmic consequences and ethical responsibility, the Buddha clearly opposed the teachings of the materialists.35 At the same time, he was able to explain the operation of karmic retribution over several lifetimes with the help of dependent co-arising (paṭicca samuppāda) and thereby without bringing in a substantial unchanging essence.36 He pointed out that the five aggregates, which together account for subjective experience, on closer investigation turn out to be impermanent and not amenable to complete personal control. Therefore a permanent and self-sufficient self cannot be found within or apart from the five aggregates.37 In this way, the Buddha’s teaching of anattā denied a permanent and inherently independent self, and at the same time affirmed empirical continuity and ethical responsibility.

X.3 EMPIRICAL SELF AND CONTEMPLATION OF THE AGGREGATES

Not only does the Buddha’s penetrating analysis of self provide a philosophical refutation of theories proposing a substantial and unchanging self, it also has an intriguing psychological relevance. “Self”, as an independent and permanent entity, is related to notions of mastery and control.38 Such notions of mastery, permanence, and inherent satisfactoriness to some degree parallel the concepts of “narcissism” and the “ideal ego” in modern psychology.39

These concepts do not refer to articulate philosophical beliefs or ideas, but to unconscious assumptions implicit in one’s way of perceiving and reacting to experience.40 Such assumptions are based on an inflated sense of self-importance, on a sense of self that continuously demands to be gratified and protected against external threats to its omnipotence. Contemplating anattā helps to expose these assumptions as mere projections.

The anattā perspective can show up a broad range of manifestations of such a sense of self. According to the standard instructions for contemplating anattā, each of the five aggregates should be considered devoid of “mine”, “I am”, and “my self”.41 This analytical approach covers not only the last-mentioned view of a self, but also the mode of craving and attachment underlying the attribution of “mine” to phenomena and the sense of “I am” as a manifestation of conceit and grasping.42 A clear understanding of the range of each aggregate forms the necessary basis for this investigation.43 Such a clear understanding can be gained through satipaṭṭhāna contemplation. In this way, contemplation of the five aggregates commends itself for uncovering various patterns of identification and attachment to a sense of self.

A practical approach to this is to keep inquiring into the notion “I am” or “mine”, that lurks behind experience and activity.44 Once this notion of an agent or owner behind experience has been clearly recognized, the above non-identification strategy can be implemented by considering each aggregate as “not mine, not I, not my self”.

In this way, contemplation of the five aggregates as a practical application of the anattā strategy can uncover the representational aspects of one’s sense of self, those aspects responsible for the formation of a self image.45 Practically applied in this way, contemplation of anattā can expose the various types of self-image responsible for identifying with and clinging to one’s social position, professional occupation, or personal possessions. Moreover, anattā can be employed to reveal erroneous superimpositions on experience, particularly the sense of an autonomous and independent subject reaching out to acquire or reject discrete substantial objects.46

According to the Buddha’s penetrative analysis, patterns of identification and attachment to a sense of self can take altogether twenty different forms, by taking any of the five aggregates to be self, self to be in possession of the aggregate, the aggregate to be inside self, or self to be inside the aggregate.47 The teaching on anattā aims to completely remove all these identifications with, and the corresponding attachments to, a sense of self. Such removal proceeds in stages: with the realization of stream-entry any notion of a permanent self (sakkāyadiṭṭhi) is eradicated, whilst the subtlest traces of attachment to oneself are removed only with full awakening.

The teaching of anattā, however, is not directed against what are merely the functional aspects of personal existence, but aims only at the sense of “I am” that commonly arises in relation to it.48 Otherwise an arahant would simply be unable to function in any way. This, of course, is not the case, as the Buddha and his arahant disciples were still able to function coherently.49 In fact, they were able to do so with more competence than before their awakening, since they had completely overcome and eradicated all mental defilements and thereby all obstructions to proper mental functioning.

A well-known simile of relevance in this context is that of a chariot which does not exist as a substantial thing apart from, or in addition to, its various parts.50 Just as the term “chariot” is simply a convention, so the superimposition of “I”-dentifications on experience are nothing but conventions.51 On the other hand, to reject the existence of an independent, substantial chariot does not mean that it is impossible to ride in the conditioned and impermanent functional assemblage of parts to which the concept “chariot” refers. Similarly, to deny the existence of a self does not imply a denial of the conditioned and impermanent interaction of the five aggregates.

Another instance showing the need to distinguish between emptiness and mere nothingness, in the sense of annihilation, occurs in a discourse from the Abyākata Saṃyutta. Here, the Buddha, on being directly questioned concerning the existence of a self (attā), refused to give either an affirmative or a negative answer.52 According to his own explanation later on, if he had simply denied the existence of a self, it might have been misunderstood as a form of annihilationism, a position he was always careful to avoid. Such a misunderstanding can in fact have dire consequences, since to mistakenly believe that anattā implies there to be nothing at all can lead to wrongly assuming that consequently there is no karmic responsibility.53

In fact, although the scheme of the five aggregates opposes the notion of a self and therefore appears essentially negative in character, it also has the positive function of defining the components of subjective empirical existence.54 As a description of empirical personality, the five aggregates thus point to those central aspects of personal experience that need to be understood in order to progress towards realization.55

A breakdown into all five aggregates might not be a matter of absolute necessity, since some passages document less detailed analytical approaches to insight. According to the Mahāsakuludāyi Sutta, for example, the simple distinction between body and consciousness constituted a sufficient degree of analysis for several disciples of the Buddha to gain realization.56 Even so, most discourses operate with the more usual analysis of the mental side of experience into four aggregates. This more detailed analysis might be due to the fact that it is considerably more difficult to realize the impersonal nature of the mind than of the body.57

Compared with the previous satipaṭṭhāna contemplations of similar phenomena (such as body, feelings, and mind), contemplation of the aggregates stands out for its additional emphasis on exposing identification-patterns. Once these patterns of identification are seen for what they really are, the natural result will be disenchantment and detachment in regard to these five aspects of subjective experience.58 A key aspect for understanding the true nature of the aggregates, and thereby of oneself, is awareness of their impermanent and conditioned nature.

X.4 ARISING AND PASSING AWAY OF THE AGGREGATES

According to the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, to contemplate the five aggregates requires a clear recognition of each, followed by directing awareness to their arising (samudaya) and their passing away (atthagama). This second stage of practice reveals the impermanent character of the aggregates, and to some extent thereby also points to their conditioned nature.59

In the discourses, contemplation of the impermanent nature of the aggregates, and thereby of oneself, stands out as a particularly prominent cause for gaining realization.60 Probably because of its powerful potential for awakening, the Buddha spoke of this particular contemplation as his “lion’s roar”.61 The reason underlying the eminent position of contemplating the impermanent nature of the aggregates is that it directly counters all conceit and “I”- or “mine”-making.62 The direct experience of the fact that every aspect of oneself is subject to change undermines the basis on which conceit and “I”- or “mine”-making take their stand. Conversely, to the extent to which one is no longer under the influence of “I” or “mine” notions in regard to the five aggregates, any change or alteration of the aggregates will not lead to sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, and despair.63 As the Buddha emphatically advised: “give up the aggregates, since none of them is truly your own!”64

In practical terms, contemplating the arising and passing away of each aggregate can be undertaken by observing change taking place in every aspect of one’s personal experience, be these, for example, the cycle of breaths or circulation of the blood, the change of feelings from pleasant to unpleasant, the variety of cognitions and volitional reactions arising in the mind, or the changing nature of consciousness, arising at this or that sense door. Such practice can then build up to contemplating the arising and passing away of all five aggregates together, when one comprehensively surveys the five aggregate- components of any experience and at the same time witnesses the impermanent nature of this experience.

Contemplating the arising and passing away of the five aggregates also highlights their conditioned nature. The interrelatedness of impermanence and conditionality with regard to the five aggregates is practically depicted in a discourse from the Khandha Saṃyutta, in which realization of the impermanent nature of the five aggregates takes place based on understanding of their conditioned nature.65 Since the conditions for the arising of each aggregate are impermanent, this passages points out, how could the conditionally arisen aggregate be permanent?

Another discourse in the Khandha Saṃyutta relates the arising and passing away of the material aggregate to nutriment, while feelings, cognitions, and volitions depend on contact, and consciousness on name-and-form.66 Dependent on nutriment, contact, and name-and-form, these five aggregates in turn constitute the condition for the arising of pleasant and unpleasant experiences. The same discourse points out that against the all too apparent “advantage” (assāda) of experiencing pleasure through any of the aggregates stands the “disadvantage” (ādīnava) of their impermanent and therefore unsatisfactory nature. Thus the only way out (nissaraṅa) is to abandon desire and attachment towards these five aggregates.

A related viewpoint on “arising” (samudaya) is provided in yet another discourse from the same Khandha Saṃyutta, which points out that delight provides the condition for the future arising of the aggregates, while the absence of delight leads to their cessation.67 This passage links the conditioned and conditioning nature of the aggregates to a comprehension of dependent co-arising. In the Mahāhatthipadopama Sutta, such comprehension of dependent co-arising leads to an understanding of the four noble truths.68

From a practical perspective, contemplation of the conditioned and conditioning nature of the five aggregates can be undertaken by becoming aware how any bodily or mental experience depends on, and is affected by, a set of conditions. Since these conditions are not amenable to full personal control, one evidently does not have power over the very foundation of one’s own subjective experience.69 “I” and “mine” turn out to be utterly dependent on what is “other”, a predicament which reveals the truth of anattā.

The one centrally important condition, however, which can be brought under personal control through systematic training of the mind, is identification with the five aggregates. This crucial conditioning factor of identification is the central focus of this satipaṭṭhāna contemplation, and its complete removal constitutes the successful completion of the practice.

According to the discourses, detachment from these constituent parts of one’s personality through contemplating the conditioned and impermanent nature of the aggregates is of such significance that direct knowledge of the arising and passing away of the five aggregates is a sufficient qualification for becoming a stream-enterer.70 Not only that, but contemplation of the five aggregates is capable of leading to all stages of awakening, and is still practised even by arahants.71 This vividly demonstrates the central importance of this contemplation, which progressively exposes and undermines self identifications and attachments and thereby becomes a powerful manifestation of the direct path to realization.