M PONY EXPRESS AND STAGE ROUTE

Eureka and Tintic Mining District

Utah’s Wild West remains nearly as wild as ever. Rugged mountain ranges and barren desert valleys have always discouraged all but the most determined individuals. Explorers, pioneers in wagon trains, Pony Express riders, and telegraph linemen crossed this inhospitable land with only the desire to reach the other side. It took the promise of gold and silver to lure large numbers of people into the jagged hills. Fading ghost towns still show the industry of the early miners. Hardy ranchers also braved the isolation to grow hay and run their cattle and sheep. The shortage of water has always been the limiting factor for development, although the U.S. military has found these remote deserts alluring for weapons testing: Several bombing ranges and munitions depots dot the countryside.

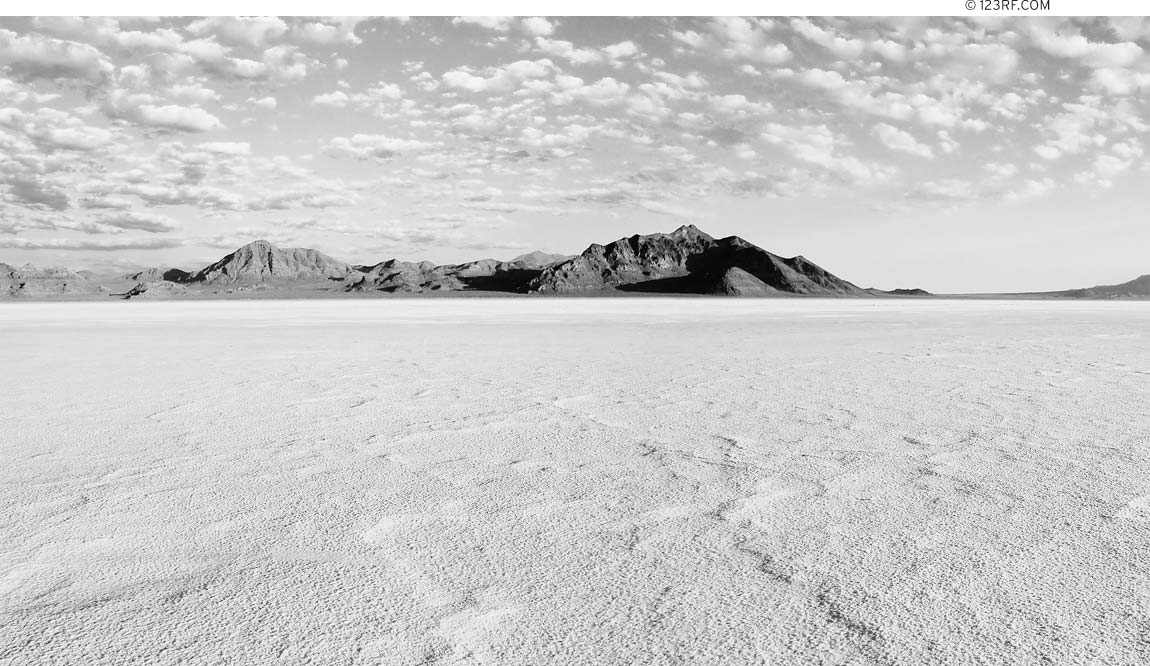

Though west-central Utah is now one of the driest parts of the Great Basin, a far different scene existed some 10,000 years ago. Freshwater Lake Bonneville then covered 20,000 square miles—one-fourth of Utah—and forests blanketed the mountains that poked above the lake waters.

Today, clouds moving in from the Pacific Ocean lose much of their moisture to the Sierra Nevada and other towering mountain ranges in California and Nevada. By the time the depleted clouds reach west-central Utah, only the Deep Creek, Stansbury, and southern Wah Wah Mountains reach high enough (over 12,000 feet) to gather sufficient rain and snow to support permanent streams.

Availability of water determines the quantity and variety of wildlife. Of the larger mammals, mule deer and pronghorn are most widespread. Elk can be found in mountainous areas east of Delta. Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep have been reintroduced in the Deep Creek Range. Herds of wild horses roam the Confusion and House Ranges. Vast numbers of birds visit Fish Springs National Wildlife Refuge and other desert oases during early-spring and late-autumn migrations.

Nomadic Paleo-Indians entered this region about 15,000 years ago as ice-age lakes such as Lake Bonneville began to shrink. These nomadic hunters and gatherers proved well suited to the drying environment, relying on small game and wild plants for food. It’s likely the modern Goshute (or Gosiute) people and the Ute people descended from these ancient inhabitants.

The Goshute once occupied northwestern Utah and adjacent Nevada; they now live on the Goshute and Skull Valley Reservations. The Utes had the greatest range of all of Utah’s indigenous people, extending from west-central Utah into Colorado and New Mexico; they are now on reservations in northeast Utah and southwest Colorado.

In the early 1860s, prospectors found placer gold deposits in the desert mountain ranges, although significant production had to wait for the arrival of the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Deposits of gold, silver, copper, lead, and zinc were found in quick succession. Active gold mining continues in a few isolated places.

Admittedly, the barren deserts and arid mountain ranges of west-central Utah won’t lure many travelers away from the ski resorts of the Wasatch Range or the red rock canyons of Utah’s national parks. However, if you enjoy solitude, expansive landscapes, and the thrill of exploring a land little changed since the nonnative explorers first arrived, this corner of Utah is for you. Most travelers will find it sufficient merely to cross the desert on one of the paved roads, either on I-80 between Salt Lake City and Wendover, Nevada, or one of the two highways that link to Great Basin National Park in eastern Nevada. As an add-on to a Utah road-trip itinerary, this region should claim no more than a day of driving and exploration.

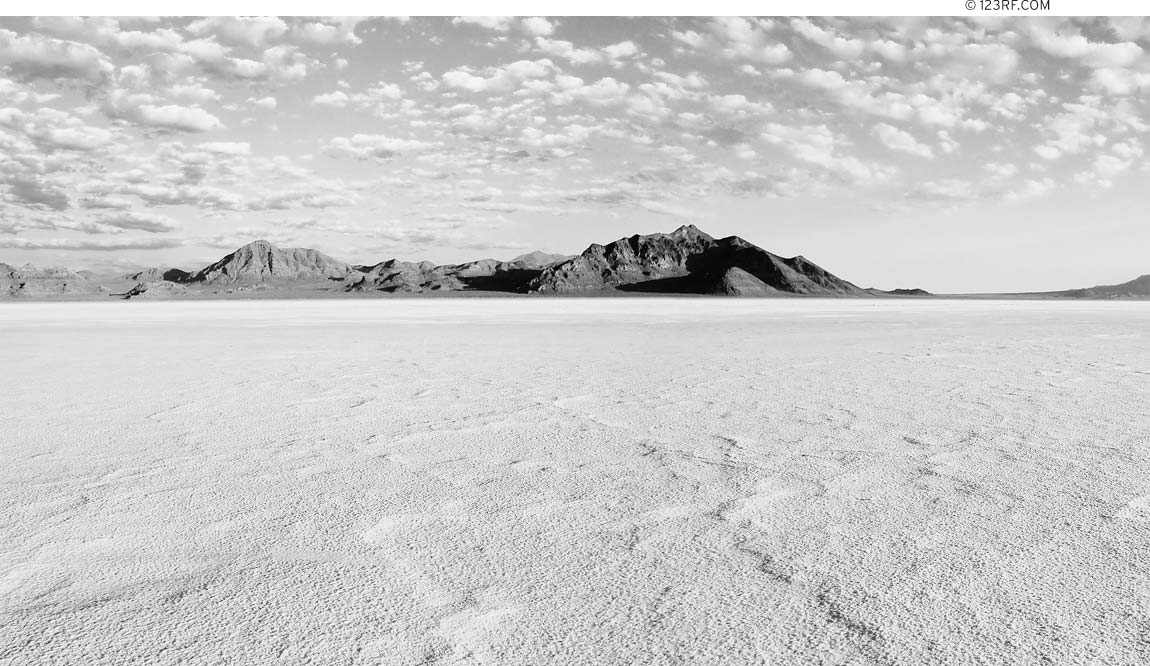

Roads do provide surprisingly good access for such a remote region. Paved I-80, U.S. 50, U.S. 6, and Highway 21 cross the Great Basin Desert, while dirt roads branch off in all directions. Following the Pony Express and Stage Route from Fairfield to Ibapah might be the most unique driving tour; you experience some of the same unfenced wilderness as the tough young Pony Express riders did. You can negotiate this and many other back roads by car in dry weather. For the adventurous, the wildly beautiful mountain ranges offer countless hiking possibilities—although you’ll have to rough it; hardly any developed trails exist.

Lake Bonneville once covered 20,000 square miles of what is now Utah, Idaho, and Nevada; when the lake broke through the Sawtooth Mountains, its level declined precipitously, leaving the 2,500-square-mile Great Salt Lake and huge expanses of salt flats to the south and west. These salt flat remnants of Lake Bonneville are almost completely white and level, and they go on for more than 100 miles. It is commonly said that one can see the earth’s curvature at the horizon, although this apparently takes a very discerning eye.

Other than the section traversed by I-80, most of the Great Salt Lake Desert is off-limits to ordinary travelers, as it is used by the military to test weapons of all sorts. Jet aircraft and helicopters occasionally break the silence in flights above the Wendover Bombing and Gunnery Range. Scientists and engineers at Dugway Proving Grounds work on chemical and biological weapons. The base developed some notoriety in 1968 after 6,500 sheep died on neighboring ranches. The military never admitted that it had released toxic chemicals, but it did compensate the ranchers. Just south of Tooele, you’ll see the neat rows of buildings across the vast Tooele Army Depot, which functions as a munitions storage site.

Wendover began in 1907 as a watering station serving construction of the Western Pacific Railroad. The highway went through in 1925, marking the community’s beginnings as a stop for travelers, and its population swelled during World War II, when the air base was active. Wendover now has the tacky grandiosity of a Nevada border town.

Wendover has a split personality—half of the town lies in Utah and half in Nevada. On both sides you’ll find accommodations and restaurants where you can take a break from long drives on I-80. Five casino hotels, eight motels, and two campgrounds offer places to stay. Six casinos on the Nevada side provide a chance to lose your money at the usual games. Most of the town’s visitor facilities line Wendover Boulevard, also known as State Highway, which parallels the interstate. Lodgings are cheaper on the Utah side. The Motel 6 (561 E. Wendover Blvd., 435/665-2267, $36-42) is one of the chain’s better efforts.

Roadside art, Metaphor: Tree of Utah, rises from the Bonneville Salt Flats along I-80.

A brilliant white layer of salt left behind by prehistoric Lake Bonneville covers more than 44,000 acres of the Great Salt Lake Desert. For much of the year, a shallow layer of water sits atop the salt flats. Wave action planes the surface almost perfectly level—some say you can see the curvature of the earth here. The hot sun usually dries out the flats enough for speed runs in summer and autumn. Cars began running across the salt in 1914 and continue to set faster and faster times. Rocket-powered vehicles have exceeded 600 miles per hour. Expansive courses can be laid out; the main speedway is 10 miles long and 80 feet wide. A small tent city goes up near the course during the annual Speed Week in August; vehicles of an amazing variety of styles and ages take off individually to set new records in their classes. The salt flats, just east of Wendover, are easy to access: Take I-80 exit 4 and follow the paved road five miles north, then east. Signs and markers indicate if and where you can drive on the salt. Soft spots underlaid by mud can trap vehicles venturing off the safe areas. Take care not to be on the track when racing events are being held.

These rugged mountains rise above the salt flats northeast of Wendover. You can visit them and their rocky canyons on a 54-mile loop drive. Take I-80 exit 4, go north 1.2 miles, turn left, and go 0.8 miles on a gravel road, then turn right at the sign for the Silver Island Mountains. The road loops counterclockwise around the mountains, crosses Lebby Pass, and returns to the junction near I-80. Another road goes north from Lebby Pass to Lucin in the extreme northwest corner of Utah. High-clearance vehicles do best on these roads, although cars can often negotiate them in dry weather. The Benchmark Road and Recreation Atlas to Utah shows approximate road alignments and terrain.

Wendover Air Force Base got its start in 1940 and soon grew to become one of the world’s largest military complexes. During World War II, crews of bombers and other aircraft learned their navigation, formation flying, gunnery, and bombing skills above the 3.5 million acres of desert belonging to the base. Only after the war ended did the government reveal that one of the bomber groups had been training in preparation for dropping atomic bombs on Japan. Little remains of the base—once a city of nearly 20,000 people. Hill Air Force Base, near Ogden, continues to use the vast military reserve for training air crews.

A small museum (345 S. Airport Apron, 866/299-2489, 8am-6:30pm daily, free) houses exhibits that illustrate the role of the airbase; vintage planes are also on display.

Here on the edges of the Great Salt Lake Desert, old buildings and tall Lombardy poplars reflect the pioneer heritage of this rural community, first settled in 1851 and named Willow Creek Fort. Grantsville stretches along Highway 138 nine miles northwest of Tooele. For hiking and camping in the Stansbury Mountains, crowned by 11,031-foot Deseret Peak, head south to the South Willow Canyon Recreation Area.

Early residents built this one-room adobe schoolhouse within the Grantsville fort walls in 1861. Today, it’s a museum honoring the Donner-Reed wagon train of 1846. These pioneers crossed the Great Salt Lake Desert to the west with great difficulty, then became trapped by snow while attempting to shortcut through the Sierra Nevada to California. Of the 87 people who started the trip, only 47 desperate pioneers survived the harsh winter—by eating boiled boots and harnesses and the frozen flesh of dead companions. Museum displays include a large collection of guns and pioneer artifacts found abandoned on the salt flats, pottery, arrowheads, and other Native American artifacts. Outside, you can see Grantsville’s original iron jail, an early log cabin, a blacksmith shop, and old wagons. Another adobe building across the street served as a church and dates from 1866. The museum is open by request during the summer (free). To view the exhibits, visit or call Grantsville City Hall (429 E. Main St., 435/884-3411 or 435/884-0824, www.donner-reed-museum.org). From the city hall, go two blocks west on Main Street to Cooley Street, then one block north to the museum.

Scuba divers can enjoy ocean-type diving in the middle of the mudflats. A natural pool at Bonneville Seabase (9390 W. Hwy. 138, 435/884-3874, www.seabase.net, 9am-3pm Thurs.-Fri., 8am-4pm Sat.-Sun., call for reservations) was found to have salinity so close to that of the ocean that marine creatures could thrive in it. Several dozen species have been introduced, including groupers, stingrays, triggerfish, damsel fish, clown fish, and lobsters. The springs are geothermally heated, so winter cold is no problem. The original pool has been expanded, and dredging created new pools. User fees run $15 pp; you can rent full equipment for scuba diving ($22) or snorkeling ($11). Bonneville Seabase is five miles northwest of Grantsville.

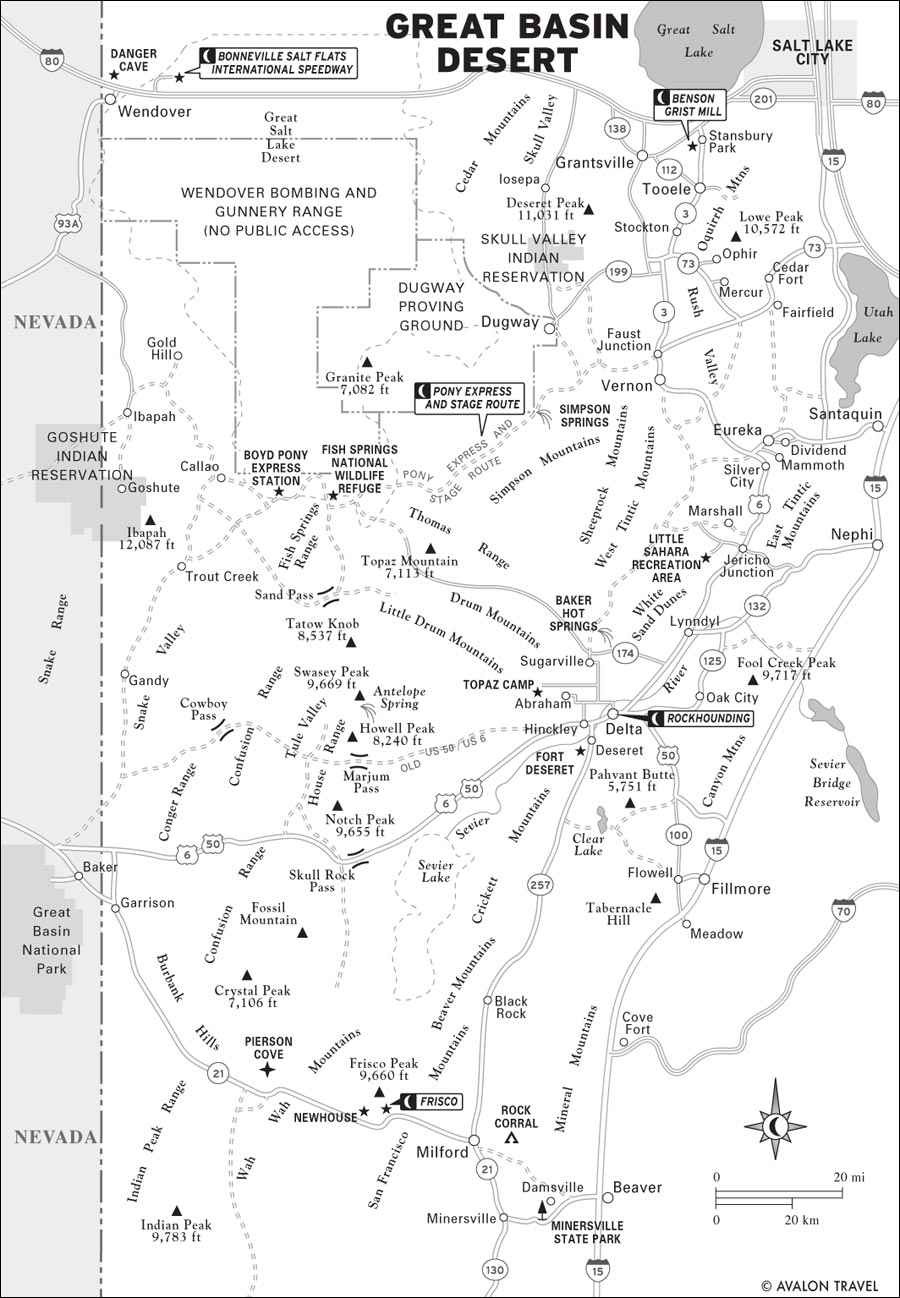

Not all of western Utah is desert, as a visit to this section of the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest (Salt Lake City Public Lands Information Center, REI store, 3285 E. 3300 S., 801/466-6411, www.fs.usda.gov) southwest of Grantsville will show. Trails lead to Deseret Peak and other good day-hiking and backcountry destinations. From the west end of Grantsville, signs for Willow Creek Recreation Area will guide you south onto West Road. Turn right onto a paved road after six miles and continue west up South Willow Canyon; the road turns to dirt at the national forest boundary. Several campgrounds are alongside West Road, which ends at Loop Campground (no water, $12).

The forested Stansbury Mountains have good hiking and camping.

The Deseret Peak Trail begins at the Loop Campground. The moderately difficult 3,600-foot climb to the summit is 7.5 miles round-trip. On a clear day atop the summit you can see much of the Wasatch Range on the eastern horizon, Great Salt Lake to the north, Pilot Peak in Nevada to the northwest, the Great Salt Lake Desert to the west, and countless desert ranges to the southwest.

To sound like a native, pronounce the town’s name “too-WILL-uh.” The origin of the word is uncertain, but it may honor the Goshute chief Tuilla. The sprawling town (pop. 30,000) lies 34 miles southwest of Salt Lake City in the western foothills of the Oquirrh (OH-ker) Mountains and has become a bedroom community for Salt Lake City workers. Mormon pioneers settled here in 1849 to farm and raise livestock, but today the major industries are the nearby Tooele Army Depot, the Dugway Proving Ground, and mining. Visitors wanting to know more about the region’s history will enjoy the town’s several museums. Other attractions in the area include a scenic drive and overlook in the Oquirrhs, the ghost town of Ophir, and hiking and camping in the nearby Stansbury Mountains.

A steam locomotive and a collection of old railroad cars surround Tooele’s original train station (1909), now the Tooele Railroad Museum (35 N. Broadway, 435/882-2836, 1pm-4pm Tues.-Sat. Memorial Day-late Sept., donation). Step inside to see the restored station office and old photos showing railroad workers, steam engines, and trestle construction. You might also meet and hear stories from retired railroad staff who volunteer as museum guides. Mining photos and artifacts illustrate life and work in the early days at Ophir, Mercur, Bauer, and other once-booming communities now faded to ghosts. Much of the old laboratory equipment and many of the tools on display came from the Tooele Smelter, built by International Smelter and Refining Company in 1907-1909. The smelter processed copper, lead, and zinc until 1972. Ore came over the Oquirrh Mountains by aerial tramway from the Bingham Mine. More than 3,000 people worked here during the hectic World War II years. A highly detailed model shows the modern Carr Fork Mill, built near Tooele but used for only 90 days before being dismantled and shipped to a more profitable site in Papua New Guinea. Two railroad cars, once part of an Air Force mobile ballistic missile train, contain medical equipment and antique furniture. Outside, kids can ride the scale railway on some Saturdays, check out a caboose, or explore a replica of a mine.

Meet Tooele’s pioneers through hundreds of framed pictures and see their clothing and other possessions at the downtown Pioneers Museum (39 E. Vine St., 10am-4pm Fri.-Sat. May-Sept., free). The small stone building dates from 1867 and once served as a courthouse for Tooele County. The little log cabin next door, built in 1856, was one of the town’s first residences.

Pioneers constructed this mill eight miles north of Tooele (325 Hwy. 138, one block west of Mills Junction, 435/882-7678, 10am-4pm Mon.-Sat. May-Oct., free), one of the oldest buildings in western Utah, in 1854. Wooden pegs and rawhide strips hold the timbers together. E. T. Benson, grandfather of past Mormon Church president Ezra Taft Benson, supervised its construction for the church. The mill produced flour until 1938, then ground only animal feed until closing in the 1940s. Local people began to restore the exterior in 1986. Much of the original machinery inside is still intact, and it offers a fascinating glimpse of 19th-century agricultural technology. Antique farm machinery, a granary, a log cabin, a blacksmith shop, and other buildings stand on the grounds to the east. Ruins of the Utah Wool Pullery, which once removed millions of tons of wool from pelts, stand to the west.

The well-preserved Benson Grist Mill is eight miles north of Tooele.

Soldier Canyon, six miles south of Tooele, draws mountain bikers. It’s a four-mile climb to the mining ghost town of Jacob City, 9,000 feet above sea level. The 40-mile gravel road that forms the Pony Express Trail from Five-Mile Pass to Simpson Springs is fun to explore on a mountain bike.

The Oquirrh Motor Inn Motel & RV Resort (8740 N. Hwy. 36, 801/250-0118, www.oquirrhinn.com, $65) is a comfortable motel north of town, near Great Salt Lake and I-80. If you are passing through, it’s a good place to stay. In town, the M American Inn and Suites (491 S. Main St., 435/882-6100, www.americaninnandsuites.com, $109-119) offers included full breakfasts, kitchenettes and efficiency kitchens, laundry facilities, a pool, and a spa. The Hampton Inn (461 S. Main St., 435/843-7700, $149-179) has a pool, a hot tub, and a free breakfast bar; each guest room has an efficiency kitchen.

For a big breakfast anytime, head north to Erda and hang with the locals at Virg’s (4025 N. Hwy. 36, 435/833-9988, 7am-3pm Mon.-Thurs., 7am-9pm Fri.-Sat., 8am-3pm Sun., $6-8). Also north of downtown is Tracks (1641 N. Main St., 435/882-4040, 11am-1am daily, $7-10), a pub with some of the best food and the liveliest atmosphere in town (nothing fancy, but it’s good bar food) and microbrews on tap. Thai House (297 N. Main St., 435/882-7579, 10am-9pm Mon.-Sat., $8-9) is another good bet. M Sostanza Grill (29 N. Main St., 435/882-4922, 11am-2:30pm and 4:30pm-10pm Tues.-Sat., $9-30) is the real surprise in Tooele, a chef-owned fine-dining restaurant.

The Tooele Chamber of Commerce (86 S. Main St., 435/882-0690 or 800/378-0690, www.exploretooele.com, 9am-4pm Mon.-Fri.) can tell you about the sights and services.

Utah Transit Authority (UTA, 435/882-9031) buses connect Tooele with Salt Lake City and other towns of the Wasatch Front Monday-Friday. The main bus stop is at Main Street and 400 South.

Picturesque old buildings and log cabins line the bottom of Ophir Canyon in the Oquirrh Mountains, which once boomed with saloons, dance halls, houses of ill repute, hotels, restaurants, and shops. In the 1860s, soldiers under General Patrick Connor heard stories of Native Americans mining silver and lead for ornaments and bullets. The soldier-prospectors tracked the mines to this canyon and staked claims. By 1870 a town was born, named after the biblical land of Ophir, where King Solomon’s mines were located. Much of the ore went to General Connor’s large smelter at nearby Stockton. Later, the St. John and Ophir Railroad entered the canyon to haul away the rich silver, lead, and zinc ores and small amounts of gold and copper. Ophir’s population peaked at 6,000, but, unlike most other mining towns of the region, Ophir never quite died. People still live here and occasionally prospect in the hills. The city hall and some houses and businesses have been restored; some of these buildings are open (11am-3pm Sat. mid-May-mid-Sept.). Other group tours can be arranged in advance (435/882-4256).

To explore Ophir’s history in some depth, schedule a visit to the Ophir Mining Museum (435/843-4002, by appointment only) at the Deseret Peak Complex in Tooele.

Paved roads go all the way into town. From Tooele, head south 12 miles on Highway 36 through Stockton, turn left and go five miles on Highway 73, and then go left 3.5 miles to Ophir.

General Connor’s soldiers also discovered silver in the canyon southeast of Ophir during the late 1860s. The mining camp of Lewiston boomed in the mid-1870s, then busted by 1880 as the deposits worked out. Arie Pinedo, a prospector from Bavaria, began to poke around the dying camp and located the Mercur Lode of gold and mercury ore. He and other would-be miners were frustrated when all attempts to extract gold from the ore failed. Then in 1890 a new cyanide process proved effective, and a new boomtown arose. Although fire wiped out the business district in 1902, Mercur was rebuilt and had an estimated population of more than 8,000 by 1910. Only three years later, the town closed up when ore bodies seemed depleted. Mining was revived in the 1930s and again in the 1980s. Thanks to strip mining, virtually nothing now remains of this ghost town.

Relive some of the Old West by driving the Pony Express route across western Utah. The scenic route goes from spring to spring as it winds through several small mountain ranges and across open plains, skirting the worst of the Great Salt Lake Desert. Interpretive signs and monuments along the way describe how the Pony Express riders swiftly brought the country closer together. The 140 miles between Fairfield in the east and Ibapah near the Nevada border provide a sense of history and appreciation for the land lost to motorists speeding along I-80.

Allow at least a full day for the drive and bring food, water, and a full tank of gas. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has campgrounds at Simpson Springs and south of Callao. No motels or restaurants line the road, but Ibapah has two gas station-grocery stores. You can travel the well-graded gravel and dirt roads on this route by a car, although a 4WD vehicle with decent clearance will make the trip much more enjoyable; watch for the usual backcountry hazards of wildlife, rocks, ruts, and washouts. Adventurous travelers may want to make side trips for rockhounding, hiking, or visiting old mining sites. Always keep vehicles on existing roads—sand and mud flats can be treacherously deceptive. Cell phone coverage is spotty along the route.

You can begin your trip down the historic route from the Stagecoach Inn at Fairfield (from Salt Lake City or Provo, take I-15 to Lehi, then go 21 miles west on Highway 73). You can also begin at Faust Junction, 30 miles south of Tooele on Highway 36, or Ibapah, 51 miles south of Wendover off U.S. 93A. The BLM has an information kiosk and small picnic area 1.8 miles west of Faust Junction. For the latest road conditions and travel information, contact the BLM Salt Lake District Office (2370 S. 2300 W., Salt Lake City, 801/977-4300). The following are points of interest along the route.

This two-story adobe and frame hotel, built in 1858, was the first stop south of Salt Lake City on the Overland Stage Route and also a stop on the Historic Pony Express Route. Inside the restored inn, you can see where weary riders slept and sat around tables swapping stories. Now part of Stagecoach Inn State Park (18035 W. 1540 N., Fairfield, 801/768-8932, 9am-5pm Mon.-Sat., $3), the inn sits across from the remains of Camp Floyd, a Civil War-era military fort. Stagecoach Inn is 36 miles northwest of Provo.

Native Americans had long used these excellent springs before the first nonnatives came through. The name honors Captain J. H. Simpson, who stopped here in 1859 while leading an army survey across western Utah and Nevada. At about the same time, George Chorpenning built a mail station here, which was later used by the Pony Express and Overland Express companies. A reconstructed stone cabin on the old site shows what the station looked like. Ruins of a nearby cabin built in 1893 contain stones from the first station. Foundations of a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp lie across the road. In 1939 the young men of the CCC built historic markers, improved roads, and worked on conservation projects. The BLM campground (nonpotable water, $5) higher up on the hillside has good views across the desert. Sparse juniper trees grow at the 5,100-foot elevation. Simpson Springs is 25 miles west of Faust Junction and 67 miles east of Callao.

The Pony Express station once located here no longer exists, but you can visit the 10,000 acres of marsh and lake of Fish Springs National Wildlife Refuge (435/831-5353, www.fws.gov/fishsprings, 7:30am-4:30pm Mon.-Fri.), which attracts abundant birdlife and wildlife. Waterfowl and marsh birds stop here in greatest numbers during their early-spring and late-autumn migrations. Many smaller birds nest here in late spring and early summer, though they’re difficult to see in the thick vegetation. Opportunistic hawks and other raptors circle overhead. A self-guided auto tour makes an 11.5-mile loop through the heart of the refuge. Most of the route follows dikes between the artificial lakes and offers good vantage points from which to see ducks, geese, egrets, herons, avocets, and other water birds. The tour route and a picnic area near the entrance are open sunrise-sunset; no camping is allowed in the refuge. Stop at the information booth near the entrance to pick up a brochure, see photos of birds found at the refuge, and read notes on the area’s history. The refuge is 42 miles west of Simpson Springs and 25 miles east of Callao.

Portions of the Pony Express station’s original rock wall remain, and signs give the history of the station and the Pony Express. Find the station 13 miles west of Fish Springs and 12 miles east of Callao.

This cluster of ranches dates from 1859, when several families decided to take advantage of the desert grasslands and good springs here. The original name, Willow Springs, had to be changed when residents applied for a post office, as too many other Utah towns had the same name. Then someone suggested Callao (locally pronounced CAL-ee-oh), because the Peruvian town of that name enjoys a similar setting in a valley backed by a high mountain. Residents raise cattle, sheep, and hay. Children go to Callao Elementary School, one of the last one-room schoolhouses in Utah. Local people believe that the Willow Springs Pony Express Station site was located off the main road at Bagley Ranch, but a BLM archaeologist contends that the foundation is on the east side of town. Callao is 67 miles west of Simpson Springs and 28 miles east of Ibapah (via the Pony Express and Stage Routes). A BLM campground (no water, free) at the site of a former CCC camp is four miles south of town, beside Toms Creek. The tall Deep Creek Range rises to the west.

The original station used by Pony Express riders was in Overland Canyon northwest of Canyon Station. Native Americans attacked in July 1863, burned the first station, and killed the Overland agent and four soldiers. The new station was built on a more defensible site. You can see its foundation and the remnants of a fortification. A signed fork at Clifton Flat points the way to Gold Hill, a photogenic ghost town six miles distant. Canyon Station is north of the Deep Creek Range, 13 miles northwest of Callao and 15 miles northeast of Ibapah. To reach Canyon Station, follow the signs for Sixmile Ranch, Overland Canyon, and Clifton Flat between Callao and Ibapah.

The tiny settlement of Ibapah is a few miles east of the Nevada state line and north of the Goshute Reservation. From Ibapah you can go north to Gold Hill ghost town (14 miles) and Wendover (58 miles) or south to U.S. 50/6 near Great Basin National Park via Callao, Trout Creek, and Gandy (90 miles).

Pronounce Ibapah “EYE-buh-paw” to avoid sounding like an outsider. Ibapah is about the same size as Callao and little more than a group of some 20 ranches. Ibapah Trading Post (435/234-1166) offers gas and groceries.

The Goshute mastered living in the harsh desert by knowing of every edible seed, root, insect, reptile, bird, and rodent, as well as larger game. Their meager diet and possessions appalled early white settlers, who referred disparagingly to the Goshute as “diggers.” Loss of land to the newcomers and dependence on manufactured food put an end to the old nomadic lifestyle. In recent times, the Goshute have gradually begun to regain their independence by learning to farm and ranch. Several hundred Goshute live on the Goshute Reservation, which straddles the Utah-Nevada border. Most of the reservation is off-limits to nonmembers without special permission.

The isolated Goshute Reservation has been in the national news thanks to protracted legal wrangling over construction of a repository on the reservation for the nuclear waste from several out-of-state atomic energy generation facilities. The federal government and Private Fuel Storage, a consortium of eight nuclear power companies, have worked out an agreement with the Goshute leadership to lease reservation land for the nuclear storage facility, which could house up to 40,000 tons of highly radioactive fuel rods. Although licensed by the Nuclear Regulatory Council in 2005, the proposal has been back and forth in the courts ever since. In 2010, Utah’s federal senators and representatives all spoke against a federal judge’s ruling that would apparently allow the repository; Representative Rob Bishop noted that “Putting this facility next to a bombing range doesn’t make sense now, and it never will.”

Miners had been working the area for three years when they founded Gold Hill in 1892. A whole treasure trove of minerals came out of the ground here—gold, silver, lead, copper, tungsten, arsenic, and bismuth. A smelter along a ridge just west of town processed the ore. But three years later, Gold Hill’s boom ended. Most people lived only in tents anyway, and soon everything but the smelter foundations and tailings was packed up. A rebirth occurred during World War I, when the country desperately needed copper, tungsten, and arsenic. Gold Hill grew to a sizable town with 3,000 residents, a railroad line from Wendover, and many substantial buildings. Cheaper foreign sources of arsenic knocked the bottom out of local mining in 1924, and Gold Hill began to die again. Another frenzied burst of activity occurred in 1944-1945, when the nation called once more for tungsten and arsenic. The town again sprang to life, only to fade just as quickly after the war ended. Determined prospectors still roam the surrounding countryside awaiting another clamor for the underground riches. Decaying structures in town make a picturesque sight. Several year-round residents live here; no scavenging is allowed. Visible nearby are the cemetery, mines, railroad bed, and smelter site. The smaller ghost town of Clifton lies over the hill to the south, but little remains; No Trespassing signs make visitors unwelcome. Good roads (partly dirt) approach Gold Hill from Ibapah, Wendover, and Callao.

The range soars spectacularly above the Great Salt Lake Desert. Few people know about the Deep Creeks despite their great heights, diverse wildlife, and pristine forests. Ibapah Peak (12,087 feet) and Haystack Peak (12,020 feet) to the north crown the range. Glacial cirques and other rugged features have been carved into the nearly white granite that makes up most of the summit ridge. Prospectors have found gold, silver, lead, zinc, copper, mercury, beryllium, molybdenum, tungsten, and uranium. You’ll occasionally run across mines and old cabins in the range, especially in Goshute Canyon. Of the six perennial streams on the east side, Birch and Trout Creeks still contain rare Lake Bonneville cutthroat trout that originated in the prehistoric lake; both creeks are closed to fishing. Other wildlife includes Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep (reintroduced), deer, pronghorn, mountain lions, coyotes, bobcats, and many birds.

The Deep Creek Range gets plenty of snow in winter, so the hiking season runs late June-late October. Aspens and some mountain shrubs put on colorful displays in September-early October. Streams in the range have good water (purify it first), but the lower canyons are often polluted by organisms that accompany cattle excrement. Carry water while hiking on the dry ridges.

Most of the canyons have roads into their lower reaches, and 4WD vehicles will be able to get farther up the steep grades than cars. A trail along Granite Creek offers the easiest approach to 12,087-foot Ibapah Peak, about 12.5 miles round-trip and a 5,300-foot elevation gain from the beginning of the jeep trail. The road to Granite Creek turns west off Snake Valley Road 10 miles south of Callao (7.8 miles north of Trout Creek Ranch). Keep left at a junction about one mile in, then follow the most-used track. The road enters Granite Canyon after three miles. The first ford of Granite Creek, 0.5 miles into the canyon, requires a high-clearance vehicle; the second, 0.8 miles farther, may require four-wheel drive. The road deteriorates into a jeep track in another 0.6 miles, at the border of Deep Creek Wilderness Study Area, but 4WD vehicles can climb the steep grade another two miles. Continue two miles on a pack trail to the beginning of a large meadow at the pass, then head cross-country 1.5 miles to the small peak (11,385 feet) just before Ibapah. A small trail on the east side of this peak continues 0.75 miles to the summit of Ibapah.

Impressive panoramas take in the rugged canyons and ridges of the Deep Creek Range below and much of western Utah and eastern Nevada beyond. Remains of a heliograph station sit atop Ibapah.

Hikers venturing into this remote range must be self-sufficient and experienced in wilderness travel. You’ll need the 7.5-minute Ibapah Peak and Indian Farm Creek topo maps for the central part of the range, the 7.5-minute Goshute and Goshute Canyon maps for the northern part, and the 15-minute Trout Creek map for the southern part. For firsthand information, contact the BLM House Range Resource Area (35 E. 500 N., Fillmore, 435/743-3100).

All approaches to the Deep Creeks involve dirt-road travel and generally sizable distances. Ibapah has the nearest gas and groceries (38 miles from the Granite Creek turnoff).

The lucky prospectors who cried “Eureka! I’ve found it!” had stumbled onto a fabulously rich deposit of silver and other valuable metals. Eureka sprang up to be one of Utah’s most important cities and the center of more than a dozen mining communities. Much can still be seen of the district’s long history—mine headframes and buildings, shafts and glory holes, old examples of residential and commercial architecture, great piles of ore tailings, and forlorn cemeteries. Exhibits at the Tintic Mining Museum in Eureka show what life was like. Paved highways provide easy access: From I-15 exit 248 for Santaquin, south of Provo, go west 21 miles on U.S. 6; from Delta, go northeast 48 miles on U.S. 6; and from Tooele, go south 54 miles on Highway 36.

Mormon stock herders began moving cattle here during the early 1850s to take advantage of the good grazing lands. Utes under Chief Tintic, for whom the district was later named, opposed the newcomers but couldn’t stop them. Mineral deposits found in the hills remained a secret of the Mormons, as church policy prohibited members from prospecting for precious metals. In 1869, though, George Rust, a non-Mormon cowboy, noticed the promising ores. Soon the rush was on—ores assaying up to 10,000 ounces of silver per ton began pouring out of the mines. Silver City, founded in 1870, became the first of many mining camps. New discoveries kept the Tintic District booming. Gold, copper, lead, and zinc added to the riches. By 1910 the district had a population of 8,000, and the end was nowhere in sight. The hills shook from underground blasting and the noise of mills, smelters, and railroads. Valuable Tintic properties kept the Salt Lake Stock Exchange busy, while Salt Lake City office buildings and mansions rose on Tintic money. Mining began a slow decline in the 1930s but has continued, sporadically, to the present. Most of the old mining camps have dried up and blown away. Eureka and Mammoth drift on as sleepy towns—monuments to an earlier era.

The ghosts of former camps can be worth a visit, although most require considerable imagination to see them as they were. Do not go near decaying structures or mine shafts. You’ll also find sites of towns that exist mostly as memories. Diligent searching through the sagebrush may uncover foundations, tailing piles, broken glass, and neglected cemeteries. Yet behind many of the sites linger dramatic stories of attempts to win riches from the earth.

Mines and tailing dumps surround weather-beaten buildings, and the area has been designated a Superfund site. Even aside from this, Eureka lacks the orderliness of Mormon towns; the main street snakes through the valley with side streets branching off in every direction. Few new buildings have been added, so the town retains an authentic atmosphere from an earlier time. Eureka now has a population of about 800, down from the 3,400 of its peak years.

The varied exhibits in the small Tintic Mining Museum (435/433-6842, 3pm-5pm Sat.-Sun. May-Sept., free) will give you an appreciation of the district and its mining pioneers. A mineral collection from the Tintic area has many fine specimens. You’ll see early mining tools, assay equipment, a mine office, a courtroom, a blacksmith shop, a 1920s kitchen, many historic photos, and displays that show social life in the early days. One display is dedicated to the influence of Jessie Knight, a Mormon financier and philanthropist. Knightsville, now a ghost town site near Eureka, gained fame as one of the few mining towns in Utah without a saloon or gambling hall. Knight also promoted mine safety and closed his mines for a day of rest on Sunday—both radical concepts at the time. You’ll find the museum galleries upstairs in City Hall (built in 1899) and next door in the former railroad depot (1925). The Tintic Tour Guide sold here describes a 35-mile loop to some of the nearby ghost towns and mines.

A large timber headframe on the west edge of town beside the highway marks one of the most productive mines in the district. John Beck arrived in 1871 and began sinking a shaft. At first people called him the “Crazy Dutchman,” but the jeers ended when he hit a huge deposit of rich ore 200 feet down. The present 65-foot-high headframe dates from about 1890; originally a large wooden building enclosed it.

Emil Raddatz bought this property on the east slope of the Tintic Mountains in 1907, believing that the ore deposits mined on the west side of the Tintics extended to here. Raddatz nearly went broke digging deeper and deeper, but the prized silver and lead ore 1,200 feet below proved him right. After his 1916 discovery, a modern company town grew up complete with a hotel, a movie theater, a golf course, and an ice plant. The miners, whose wages had been paid partly in stock certificates, chose the name Dividend because they had been so well rewarded. Mining continued until 1949, producing $19 million in dividends, but today only foundations, mine shafts, and large piles of tailings remain. A loop road east of Eureka will take you to this site and other mining areas. Walking or driving off the road is forbidden because of mine shafts and other hazards. Although the road is paved, some sections are badly potholed and need to be driven slowly. From downtown Eureka, go east 1.5 miles on U.S. 6 and turn right on the Dividend road (0.1 miles east of milepost 141); the road climbs into hills and passes the Eureka Lily headframe and mine on the left after 2.5 miles. Continue 0.3 miles to Tintic Standard number 1 shaft on right, then 0.3 miles more to the site of Dividend and the number 2 shaft (signed); the road ends at a junction 0.9 miles farther. Turn left and go 0.7 miles to U.S. 6, four miles east of Eureka. The Sunshine Mining Company currently operates the Burgin Mine, about one mile east of Dividend.

Prospectors made a “mammoth” strike over the hill south of Eureka in 1870. The town of Mammoth and more mines, mills, and smelters followed. The eccentric mining engineer George Robinson built a second town, immodestly named after himself, one mile down the valley. Both towns prospered, growing together and eventually becoming just Mammoth. Nearly 3,000 people lived here when activity peaked in 1900-1910. Then came the inevitable decline as the high-grade ores worked out. By the 1930s, Mammoth was well on its way to becoming a ghost town, although people still live here today and have preserved some of the old buildings. The Mammoth glory hole and mine buildings overlook the town at the head of the valley. Ruins of smelters and mines cling to hillsides. From Eureka, go southwest 2.5 miles on U.S. 6, then turn left (east) and go one mile on a paved road.

Optimistic prospectors named their little camp for the promising silver ore, but a city it was not to be. The cost of pumping water out of the mines cut too deeply into profit margins, and a 1902 fire nearly put an end to the town. At that point Mormon financier Jessie Knight stepped in to improve the mines and rebuild the town. He also built a smelter and later a mill. Silver City reached its peak around 1908, before declining to ghost-town status in the 1930s. You can’t miss the giant piles of tailings (light colored) and slag (dark colored) from the smelter and mill at the old town site. Extensive concrete foundations show the complexity and size of the operations. Sagebrush has reclaimed the rest of the town, of which only debris and foundations survive. Some diehards still mine, prospect, and reprocess the old smelter waste products. The Silver City ghost town site is 3.3 miles southwest of Eureka (0.8 miles past the Mammoth turnoff), just off U.S. 6.

Black Crook Peak (elev. 9,275 feet) tops this little-known range northwest of Eureka. Mining, which peaked in the early 1900s, still continues on a small scale for silver, lead, and zinc. Bald eagles winter here approximately December-March; their numbers appear to fluctuate with the rabbit population. Anglers can try for brook and brown trout in Vernon Reservoir and Vernon and Bennion Creeks.

The small Little Valley Campground is open May-November (no water, free). The Spanish Fork Ranger District Office (44 W. 400 N., Spanish Fork, 435/798-3571) of the Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest manages this area, known as the Vernon Division.

To get to the Sheeprock Mountains, follow Highway 36 northwest 17 miles from Eureka (or south 42 miles from Tooele) to a junction signed Benmore, just east of Vernon; turn south and go five miles to Benmore Guard Station, then left and 2.5 miles for Vernon Reservoir. Little Valley Campground is off to the right in a side valley, 2.3 miles past the reservoir. A road that comes in via Lofgreen is a bit rough for cars. None of these roads are recommended in wet weather.

Sand dunes have made a giant sandbox between Eureka and Delta. Managed by the BLM, the recreation area covers 60,000 acres of free-moving sand dunes, sagebrush flats, and juniper-covered ridges. Elevations range from about 5,000 to 5,700 feet. Varied terrain provides challenges for dune buggies, motorcycles, and 4WD vehicles. While off-road vehicles can range over most of the dunes, areas near White Sands and Jericho Campgrounds have been set aside for children. The Rockwell Natural Area in the western part of the dunes protects 9,150 acres for nature study.

The dunes originated 150 miles away, as sandbars along the southern shore of Lake Bonneville, roughly 10,000 years ago. After the lake receded, prevailing winds pushed the exposed sands on a slow trek northeastward at a rate of about 18 inches per year. Sand Mountain, however, deflected the winds upward, and the sand grains piled up into large dunes downwind. Lizards and kangaroo rats scamper across the sand in search of food and in turn are eaten by hawks, bobcats, and coyotes. Pronghorn and mule deer live here year-round. Juniper, sagebrush, greasewood, saltbush, and grasses are the most common plants. An unusual species of four-wing saltbush (Atriplex canescens) grows as high as 12 feet and is restricted to the dunes area.

A visitors center near the entrance is open irregular hours. Three developed campgrounds with water (White Sands, Oasis, and Jericho) and a primitive camping area (Sand Mountain) are open year-round. In winter, water is available only at the visitors center on the way in. Visitors to Little Sahara pay $18 per vehicle, which includes use of campgrounds. For more information, contact the BLM Office (15 E. 500 N., Fillmore, 435/743-3100).

The entrance road is 4.5 miles west of Jericho Junction, which is 17 miles south of Eureka, 31 miles west of Nephi (I-15 exits 222 and 228), and 32 miles northeast of Delta.

The barren Pahvant Valley along the lower Sevier River was considered a wasteland until 1905, when some Fillmore businessmen purchased water rights from Sevier River Reservoir and 10,000 acres of land. The farm and town lots they sold became the center of one of Utah’s most productive agricultural areas. Other hopeful homesteaders who settled farther from Delta weren’t as fortunate. Thousands of families bought cheap land nearby but found the going very difficult. Troubles with the irrigation system, poor crop yields, and low market prices forced most to leave by the late 1930s. A few decaying houses and farm buildings mark the sites of once-bustling communities. Farmers near Delta raise alfalfa seed and hay, wheat, corn, barley, mushrooms, and livestock. The giant coal-burning Intermountain Power Project, which mostly supplies Los Angeles, and the Brush Wellman beryllium mill have helped boost Delta’s population to about 3,200. Miners have been digging into the Drum Mountains northwest of Delta since the 1870s for gold, silver, copper, manganese, and other minerals; some work still goes on there. The beryllium processed near Delta comes from large deposits of bertrandite mined in open pits in the Topaz and Spors Mountains farther to the northwest.

Although not exactly a ghost town, the area northeast of Delta is pretty sleepy.

For travelers, Delta makes a handy base for visiting the surrounding historic sites, rockhounding, and exploring nearby mountain ranges. In downtown Delta, the Great Basin Museum (328 W. 100 N., 435/864-5013, 10am-4pm Mon.-Sat., free) presents a varied collection of pioneer photos and artifacts, arrowheads, a Topaz Camp exhibit, fossils, and minerals; antique farm machinery stands outside.

A pioneer log cabin (built 1907-1908), now on Main Street in front of Delta’s municipal building, was the second house and the first post office in Melville, which was later known as Burtner, and finally as Delta in 1910. Historical markers near the cabin commemorate the Spanish Dominguez-Escalante Expedition, which passed to the south in 1776, and the Topaz Camp for Japanese Americans interned during World War II.

Beautiful rock, mineral, and fossil specimens await discovery in the deserts surrounding Delta. Sought-after rocks and minerals include topaz, bixbyite, sunstones, geodes, obsidian, muscovite, garnet, pyrite, and agate. Some fossils to look for are trilobites, brachiopods, horn coral, and crinoids. The Delta Chamber of Commerce (80 N. 200 W., 435/864-4316, www.millardcountytravel.com, 10am-5pm Mon.-Fri.) is a good source of local information; it publishes the free Discovering Millard County brochure, which has great information on specific rocks, such as obsidian, sunstones, and topaz, and where to find them.

You can see gemstones from the area at West Desert Collectors (278 W. Main St., 435/864-2175) and Tina’s Jewelry and Minerals (320 E. Main St., 435/864-2444).

For more of an expedition, head to Topaz Mountain. From U.S. 50/6, about 11 miles northeast of Delta, turn west onto the paved Brush Wellman Road and follow it for 37.3 miles to a point where you can clearly see Topaz Mountain. Follow the sign for Topaz Mountain and head up the dirt road, north along the east side of the mountain. Several spur trails lead to rockhounding sites. Primitive camping is permitted, but there is no water.

A commercial enterprise makes it easy, though not cheap, to dig for trilobites and other marine fossils. U-Dig Fossils (435/864-3638, 9am-6pm Mon.-Sat. Apr.-Oct.) is a private quarry located in Antelope Springs, 52 miles west of Delta. It’s best to come prepared with work gloves, sturdy shoes, and protective eyewear; U-Dig provides hammers, buckets, and advice. Two hours of digging costs $28 over age 16; it’s $16 ages 8-16, and free under age 8. Call ahead, because if business is slow, the quarry closes early. From Delta, head west on U.S. 50/6, turn north at the U-Dig sign between mileposts 56 and 57, and continue another 20 miles north to the site.

Delta has several motels on or close to Main Street. The Budget Motel (75 S. 350 E., 435/864-4533, $45-55) is a good bet for those who don’t need many amenities. For a step up in style and amenities, the Days Inn Motel (527 E. Topaz Blvd., 435/864-3882 or 435/864-3882, $79-99) has a heated outdoor pool and allows pets.

Antelope Valley RV Park (760 W. Main St., 435/864-1813 or 800/430-0022, Apr.-Nov., $28) is on the west edge of downtown.

East of Delta, the Oak Creek Campground (elev. 5,900 feet, has water, late May-early Oct., $10) is a U.S. Forest Service campground along Oak Creek amid Gambel oak, cottonwood, maple, and juniper trees on the west side of the Canyon Mountains. Canyon walls cut by the creek reveal layers of twisted and upturned rock. Oak Creek usually has good fishing for rainbow trout; much of its flow comes from a spring at the upper end of the campground. From Delta, go east 14 miles on U.S. 50 and Highway 125 to the small farming town of Oak City, then turn right and go four miles on a paved road.

After a hot afternoon of rockhounding, a burger and shake at the Delta Freeze (411 E. Main St., 435/864-4790, 10am-7pm daily, $4-9) may be just what you need. If you’d rather sit down and dine on steak, head upstairs to The Loft. There’s Mexican food at El Jalisciense Taco Shop (396 W. Main St., 435/864-3141, 5:30am-10pm daily, $4-9).

Delta Chamber of Commerce (80 N. 200 W., 435/864-4316, www.millardcountytravel.com, 10am-5pm Mon.-Fri.) can tell you about services in town and sights in the surrounding area.

The local swimming pool (201 E. 300 N., 435/864-3133) is indoors.

Topaz is easily Utah’s most dispiriting ghost town site. Other ghost towns had the promise of precious metals or good land to lure their populations, but those coming to Topaz had no choice—they had the bad fortune to be of the wrong ancestry during the height of World War II hysteria. About 9,000 Japanese—most of whom were American citizens—were brought from the West Coast to this desolate desert plain in 1942. Topaz sprang up in just a few months and included barracks, communal dining halls, a post office, hospital, schools, churches, and recreational facilities. Most internees cooperated with authorities; the few who did not were shipped off to a more secure camp. Barbed wire and watchtowers with armed guards surrounded the small city, which was actually Utah’s fifth-largest community for a time. All internees were released at war’s end in 1945, and the camp came down almost as quickly as it had gone up. Salvagers bought and removed equipment, buildings, barbed wire, telephone poles, and even street paving and sewer pipes. An uneasy silence pervades the site today. Little more than the streets, foundations, and piles of rubble remain. You can still walk or drive along the streets of the vast camp, which had 42 neatly laid-out blocks. A concrete memorial stands at the northwest corner of the site.

One way to get here is to go six miles west from Delta on U.S. 50/6 to the small town of Hinckley, turn right (north) and go 4.5 miles on a paved road (some parts are gravel) to its end, turn left (west) and go 2.5 miles on a paved road to its end in Abraham, turn right (north) and go 1.5 miles on a gravel road to a stop sign, then turn left and go three miles on a gravel road; Topaz is on the left.

If you’re willing to go a little out of your way for a soak, head to Baker Hot Springs, near the eastern base of Fumarole Butte. This shield volcano, about 21 miles northwest of Delta, has undeveloped hot springs; several cement pools and a system of pipes allows users to control their soaking temperature. From Delta, take U.S. 6 north 11 miles, then turn west onto Brush Wellman Road and continue 24 miles. Turn north on a dirt road on the eastern edge of the volcano, and follow it 7.25 miles to the hot springs.

The House Range, about 45 miles west of Delta, offers great vistas, scenic drives, wilderness hiking, and world-famous trilobite fossil beds. Swasey Peak (elev. 9,669 feet) is the highest point. From a distance, however, Notch Peak’s spectacular 2,700-foot face stands out as the most prominent landmark in the region. What the 50-mile-long range lacks in great heights, it makes up for in massive sheer limestone cliffs and rugged canyons. Precipitous drops on the western side contrast with a gentler slope on the east. Bristlecone pines grow on the high ridges of Swasey and Notch Peaks; the long-lived trees are identified by inward-curving bristles on the cones and by needles less than 1.5 inches long in clusters of five. Wild horses roam Sawmill Basin to the northeast of Swasey Peak.

Mining in the range has a long history. Stories tell of finding old Spanish gold mines with iron tools in them that crumbled at a touch. More recent mining for tungsten and gold has occurred on the east side of Notch Peak. Outlaws found the range a convenient area in which to hide out; Tatow Knob, north of Swasey Peak, for example, was a favorite spot for horse thieves. Death Canyon got its name after a group of pioneers became trapped and froze to death; most maps now show it as Dome Canyon.

The dirt roads here can be surprisingly good. Often you can zip along as if on pavement, but watch for loose gravel, large rocks, flash floods, and deep ruts that sometimes appear on these backcountry stretches. Roads easily passable by car connect to make a 43-mile loop through Marjum and Dome Canyon Passes. You’ll have good views of the peaks and go through scenic canyons on the west side of both passes. Drivers with high-clearance vehicles can branch off on old mining roads or drive past Antelope Spring to Sinbad Overlook for views and hiking near Swasey Peak.

Shale beds near Antelope Spring have given up an amazing quantity and variety of trilobite fossils dating from about 500 million years ago. Professional collectors have leased a trilobite quarry, so you’ll have to collect outside. Trilobites can also be found near Swasey Spring and near Marjum Pass. Flat-edged rock hammers work best to split open the shale layers.

During World War I a hermit took a liking to the House Range and built a one-room cabin in a small cave, where he lived until his death. He entertained visitors with a special home brew. To visit the cabin, walk 0.25 miles up a small side canyon from the road; the cabin is on the right side of the road that comes down to the west from Marjum Pass.

Several roads connect U.S. 50/6 with the loop through Marjum and Dome Canyon Passes. Going west from Delta on U.S. 50/6, you have the choice of the following turnoffs: After 10 miles, turn right and go 25 miles at the fork for the unpaved old U.S. 50/6; after 32 miles, turn right and go 10 miles on a road signed Antelope Spring; after 42 miles, turn right and go 16 miles on a road also signed Antelope Spring; or after 63 miles (30 miles east of the Utah-Nevada border), turn right and go 14 miles on a road signed Painter Spring.

Most hiking routes travel cross-country through the wilderness. Springs are very far apart and are sometimes polluted, so carry water for the whole trip. Bring topo maps and a compass; help can be a long way off if you make a wrong turn. Because of the light precipitation, the hiking season at high elevations can last late April-late November. You can visit most destinations, including Swasey and Notch Peaks, on a day hike. These peaks offer fantastic views over nearly all of west-central Utah and into Nevada. For more information on the House Range, contact the BLM office (35 E. 500 N., Fillmore, 435/743-6811).

The trip to Swasey Peak makes a good half-day hike and is usually done as a loop. Total distance for the moderately difficult trip is about 4.5 miles, with a 1,700-foot elevation gain to the summit (elev. 9,669 feet). Drive to the Antelope Spring turnoff, 2.5 miles east of Dome Canyon Pass, and follow the well-used Sinbad Overlook road 3.3 miles, passing the spring and trilobite area, up a steep grade to a large meadow below Swasey Peak. Cautiously driven cars might be able to get up this road, although it’s safer to park low-clearance vehicles and walk the last 1.5 miles. (Nonhikers with suitable vehicles can drive to Sinbad Overlook for views at the end of the road.) From the large meadow at the top of the grade, head northeast on foot up the ridge, avoiding cliffs to the left. After 1.25 miles, you’ll reach a low summit; continue 0.5 miles along the ridgeline, curving west toward Swasey Peak. To complete the loop, descend 0.5 miles to the northwest along a ridge to bypass some cliffs, then head southwest 0.75 miles to the end of Sinbad Overlook road.

From here, it’s an easy 1.5 miles by road back to the start; Sinbad Spring and a grove of ponderosa pines are about halfway. No signs or trails mark the route, but hikers experienced with maps shouldn’t have any trouble. Topo maps for this hike are the 7.5-minute Marjum Pass and Swasey Peak. Route-finding is easier when hiking the loop in the direction described. You’ll get a close look at the mountain mahogany on Swasey Peak. Some thickets of this stout shrub have to be crossed; wear long pants to protect your legs.

The 2,700-foot sheer rock wall on the western face of prominent Notch Peak is only 300 feet shorter than El Capitán in Yosemite. Most hikers prefer the far easier summit route on the other side via Sawtooth Canyon. This moderately difficult canyon route is about nine miles round-trip and has a 1,700-foot elevation gain. Bring water, as no springs are in the area. Like the Drum Mountains, Notch Peak has a reputation for strange underground noises. The 15-minute Notch Peak topo map is needed as much for navigating the roads to the trailhead as for the hiking, although the Discovering Millard County booklet (free from Delta Chamber of Commerce, 80 N. 200 W., Delta) also has a good map to get you to the trailhead. First, take Antelope Spring Road to the signed turnoff for Miller Canyon, 4.5 miles north of milepost 46 on U.S. 50/6 (42 miles west of Delta) and 11.5 miles south of old U.S. 50/6 (35 miles west of Delta). Turn west and go 5.3 miles on Miller Canyon Road, then bear left to Sawtooth Canyon at a road fork.

A stone cabin 2.5 miles farther on the right marks the trailhead. The cabin is owned and used by people who mine in the area. Follow a rough road on foot into Sawtooth Canyon. After 0.75 miles, the canyon widens where two tributaries meet; take the left fork in the direction of Notch Peak. A few spots in the dry creek bed require some rock-scrambling. Be on the lookout for flash floods if thunderstorms threaten.

After about three miles, the wash becomes less distinct; continue climbing to a saddle visible ahead. From here, a short but steep 0.25-mile scramble takes you to the top of 9,655-foot Notch Peak and its awesome drop-offs. Alternative routes up Notch Peak offer challenges for the adventurous. The other fork of Sawtooth Canyon can be used, for example, and a jeep road through Amasa Valley provides a northern approach.

The Confusions lie in a long jumbled mass west of the House Range. Fossil Mountain, in the southeast part of the Confusions, has an exceptional diversity of marine fossils, many very rare. Thirteen fossil groups of ancient sea creatures have been found in rocks of early Ordovician age (350-400 million years ago). Fossil Mountain stands 6,685 feet high on the west edge of Blind Valley. A signed road to Blind Valley turns south off U.S. 50/6 between mileposts 38 and 39 (54 miles west of Delta). Fossil Mountain is about 14 miles south of the highway.

What remains of this fort represents a fading piece of pioneer history. Mormon settlers hastily built the adobe-walled fort in only 18 days in 1865 for protection against Native Americans during the Black Hawk War. The square fort had walls 550 feet long and 10 feet high, with gates in the middle of each side. Bastions were located at the northeast and southwest corners. Native Americans never attacked the fort, but it came in handy for penning up cattle at night. Parts of the wall and stone foundation still stand. From Delta, go west five miles on U.S. 50/6, then turn left (south) and go 4.5 miles on Highway 257. The site is on the west side of the road near milepost 65, about 1.5 miles south of the town of Deseret.

A natural rock formation seven miles southwest of Deseret bears a striking resemblance to the Mormon prophet Joseph Smith. To see the profile, you have to view the rock from the west. From the town of Deseret, go south three miles on Highway 257, then turn right (west) and go four miles (it should be signed) on a dirt road. A short hike at road’s end leads up a lava flow to the stone face.

Lakes and marsh country offer ducks, Canada geese, and other birds a refreshing break from the desert. Roads cross Clear Lake on a causeway and lead to smaller lakes and picnic areas to the north. The Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (801/864-3200) manages the area. From the junction of U.S. 50/6 and Highway 257, west of Delta, go south 15.5 miles on Highway 257, then turn left (east) and go seven miles on a good gravel road.

Locally known as Sugar Loaf Mountain, this extinct volcano rises 1,000 feet above the desert floor. Waters of prehistoric Lake Bonneville leveled off the large terrace about halfway up. Remnants of a crater, now open to the southwest, are on this level. Another terrace line is at the bottom of the butte. Hikers can explore the volcanic geology and expansive panoramas as well as visit the curious ruins of a windmill. Construction of the wind-powered electric power station began in 1923 but was never completed. A large underground room and two concentric rings of concrete pylons give an eerie Stonehenge-like atmosphere to the butte.

The easiest way up is an old road on the south side that goes to the windmill site. From Clear Lake, continue east 3.3 miles to the second signed turn on the left for Pahvant Butte Road (3 miles); Sugarloaf Well number 1 is eight miles. Turn left at the sign, travel 3.5 miles, and then turn left and go 0.5 miles on Pahvant Butte Road. Park before the road begins a steep climb. Daredevils in 4WD vehicles have tried going straight up the slope from here, but the real road turns right and follows switchbacks 0.7 miles to the windmill site. This last 0.7 miles is closed to vehicles because of the soft volcanic rock, but it’s fine for walking; the elevation gain is about 400 feet. Pahvant Butte’s highest point is about 0.5 miles to the north and 265 feet higher; you’ll have to find your own way across if you’re headed there. Dirt roads encircle Pahvant Butte and go northeast to U.S. 50 and southeast to Tabernacle Hill and Fillmore. The Tabernacle Hill area provides good examples of volcanic features.

Miners on their way to Frisco and Newhouse crossed the Beaver River at a ford below a stamp mill, so Milford (pop. 1,400) seemed the logical name for the town that grew up here. Most of Milford’s businesses in the early days supplied the mining camps. Today the town serves as a center for the railroad, nearby farms, and a geothermal plant. Steam from wells at the Blundell Geothermal Plant, 13 miles northeast of town, produces electricity for Utah Power and Light. Travelers heading west will find Milford their last stop for supplies before the Nevada border. Milford is at the junction of Highways 21 and 257, which is 77 miles south of Delta and 32 miles east of Beaver. Baker, Nevada, is 96 miles northwest.

On the west edge of town, the pet-friendly M Oak Tree Inn (777 W. Hwy. 21, 800/523-8460, $75-90) has quiet, comfortable guest rooms with microwaves and fridges as well as a fitness center. Guests get a free breakfast next door at Penny’s Diner (435/387-5266, $6-20), a pretty good 24-hour restaurant. Pavilion Park (300 N. and 300 W., has water, year-round) has a free camping area just beyond the high school grounds.

The large reservoir at Minersville Reservoir Park (435/438-5472, day-use $5) has year-round fishing for rainbow trout and smallmouth bass and ice fishing in winter. Be sure to check with the rangers for information about fishing regulations for the park. Bait fishing is not allowed, and there are special catch limits. Most people come here to fish, although some visitors go sailing or waterskiing; in dry years the lake is less appealing. Park facilities include picnic tables, campsites (electric and water hookups, $13), restrooms with showers, a paved boat ramp, a fish-cleaning station, and a dump station. Reservations are a good idea on summer holidays. In winter, the restrooms may be closed, but water is available. Minersville Reservoir is just off Highway 21 in a sage- and juniper-covered valley eight miles east of Minersville, 18 miles southeast of Milford, and 14 miles west of Beaver.

A coal train passes windmills near Milford.

Frisco Peak (elev. 9,660 feet) crowns this small range northwest of Milford. The Wah Wah Valley and Mountains lie to the west. Silver strikes in the San Francisco Mountains in the 1870s led to the opening of many mines and the founding of the towns of Newhouse and Frisco. By 1920 the best ores had given out and both communities turned to ghost towns. A jeep road goes to the summit of Frisco Peak.

The Horn Silver Mine, developed in 1876 at the south end of the San Francisco Mountains, was the first of several prolific silver producers. Smelters and charcoal ovens to fuel them sprouted up to process the ore. A wild boomtown developed as miners flocked to the new diggings. The railroad reached Frisco in 1880 and later extended to nearby Newhouse. Frisco’s population of 6,000 included quite a few gamblers and other shady characters. Twenty-three saloons labored to serve the thirsty customers. Gunfights became almost a daily ritual for a while, keeping the cemetery growing. But it all came to an end early in 1885, when rumblings echoed from deep within the Horn Silver Mine between shifts. The foreman luckily delayed sending the next crew down, and a few minutes later the whole mine collapsed with a deafening roar that broke windows in Milford, 15 miles away. Out of work, most of the miners and businesspeople moved on. More than $60 million in silver and other valuable ores had come out of the ground in the mine’s 10 frenzied years. Some mining has been done on and off since, but Frisco has died.

Today Frisco is one of Utah’s best-preserved mining ghost towns, with about a dozen stone or wood buildings surviving. A headframe and mine buildings, still intact, overlook the town from the hillside. Five beehive-shaped charcoal kilns stand on the east edge of Frisco. You can see the kilns and the town site if you look north from Highway 21 (between mileposts 62 and 63), 15 miles west of Milford. Dirt roads wind their way in; to reach the main town site and kilns, head north and take the first right turn. Follow this rough but drivable road to the town site.

To reach the town cemetery, head north at the main turnoff, but do not turn right toward the town—keep going straight. Stop and park where the road splits, then walk west toward the cemetery (visible from the parking area).

Prospectors discovered silver deposits in 1870 on the southwest side of the San Francisco Mountains but lacked the funds to develop them. Mining didn’t take off until 1900, when Samuel Newhouse financed operations. A sizable town grew here as ore worth $3.5 million came out of the Cactus Mine. Citizens maintained a degree of law and order not found in most mining towns: Even the saloon and the working girls had to operate outside the community. Deposits of rich ore ran out only 10 years later, and the town’s inhabitants departed. The railroad depot was moved to a nearby ranch, and other buildings went to Milford. Today, Newhouse is a ghostly site with about half a dozen concrete or stone buildings standing in ruins. Foundations of a smelter, a mill, other structures, railroad grades, and lots of broken glass remain. A good dirt road turns north and runs two miles to the site from Highway 21 (between mileposts 57 and 58), 20 miles west of Milford.

Beyond the San Francisco Mountains, the Wah Wah Mountains extend south about 55 miles in a continuation of the Confusion Range. Elevation ranges from 6,000 to more than 9,000 feet. The name comes from a Paiute term for salty or alkaline seeps. Sparse sagebrush, juniper, and piñon pine cover most of the land. Aspen, white fir, ponderosa pine, and bristlecone pine grow in the high country. Mule deer, pronghorn, and smaller animals roam the mountains. Carry water, maps, and a compass into this wild country. Few people visit the Wah Wahs despite their pristine ecosystem, so here’s your chance to get there before the crowds.

The snow-white pinnacle of Crystal Peak at the north end of the Wah Wah Mountains stands out as a major landmark. The soft white rock of the peak is tuff from an ancient volcano thought to predate the block-faulted Wah Wahs. The best way to climb the peak (elev. 7,106 feet) is to ascend the ridge just south of it from the east, then follow the ridge northeast up the peak.