Facing up to a multi-channel future

Growth in sales… growth in profitability… growth in customers… growth in number of stores… growth in distribution centers… growth in markets… growth in associates… growth in market share… growth in shareholders… growth in suppliers… growth in financial strength. No word better describes Walmart than does growth.1

WALMART

This is an excerpt from Walmart’s 1982 annual report, the year that sales reached $2.5 billion. Today, it’s more like half a trillion dollars.2 The word growth has certainly been an accurate depiction, if not understatement, of Walmart for the past 30 years, but the big question on everyone’s minds is – just how much of it is left?

Going back to the early 1980s, Little Rock, Arkansas and Joplin, Missouri were among Walmart’s largest metropolitan areas.3 At that time, Walmart was still focused on its small-town strategy, targeting the rural areas of America that its competitors had originally considered too small to support a store of Walmart’s size: ‘… the first big lesson we learned was that there was much, much more business out there in small-town America than anybody, including me, had ever dreamed of’, Mr Walton wrote.4 While discounters such as Kmart believed that a catchment area of 50,000 people was the minimum needed to support a discount store,5 Walmart proved them wrong by opening its first store in Rogers, Arkansas, a town of fewer than 10,000 inhabitants.6 In fact, back in the early Walmart days, Mr Walton’s wife Helen refused to live in towns with more than 10,000 people.

Walmart may have broken all the rules of traditional retailing but its initial small-town strategy wasn’t about avoiding the competition – it was about serving those who were being underserved, something that still rings true for Walmart today, albeit in a different form. Today, Walmart’s influence across the US heartland is unmatched, and now the retailer is looking to prove its competitors wrong once again by reaching out to a new, unconventional consumer: the city dweller.

With approximately 3,000 domestic Supercenters and another 700 discount stores, today there is one big-box Walmart store for approximately every 85,000 people.7 This compares to one Target for every 175,000 people or one Kroger for every 125,000 people. Walmart has recognized that the end is nigh for its larger US formats, which is forcing the retailer to shift its focus towards smaller stores in US urban areas and so-called food deserts.

At the same time, it’s important to remember that US consumers are rapidly changing the way they engage with retailers, utilizing technology and social media to help make purchasing decisions and increasingly transacting online. It’s fair to say that a ‘one size fits all’ cookie-cutter approach to retailing is simply no longer valid: a multi-channel strategy encompassing both proximity-led formats and e-commerce will be key for future growth.

Before we get into how the Walmart of 2020 may look – the king of small? the urban pioneer? the new Amazon? – it’s important to look back at what Walmart has achieved in its first 50 years of retailing.

The Supercenter and Walmart’s rise to grocery domination

The world’s largest retailer has never been ashamed of stealing a good idea. Its self-service discount stores were based on the success of early discounters such as Ann & Hope and Spartan’s.8 Its Sam’s Club format was a carbon copy of Price Club. Referring to a dinner he had with Price Club founder Sol Price in 1983, Sam Walton writes in his autobiography: ‘… We dropped down to have dinner with Sol and his wife Helen at Lubock’s. And I admit it. I didn’t tell him at the time I was going to copy his program, but that’s what I did.’9 Today, Sam’s Club is a $50 billion business.10

What eventually became the Walmart Supercenter concept (Hypermart preceded the Walmart Supercenter as the company’s foray into hypermarket retailing) was the result of Sam Walton travelling the globe and borrowing ideas from hypermarkets overseas. Walton became inspired by these big-box formats in Europe, South Africa, South America and Australia, with a particular admiration for Carrefour in France and Brazil. ‘I argued that everybody except the United States was successful with this concept and we should get in on the ground floor with it. I was certain this was where the next competitive battlefield would be.’11

This was the late 1980s, and back at home there was a tremendous amount of consolidation taking place in the US grocery sector. As a result of the lack of competition, food prices rose as the supermarkets cushioned their bottom lines. In fact, the price of food sold at supermarkets nationwide grew at twice the rate of the producer-price index from 1991 through 2001. This meant that Walmart could come in and reduce prices by up to 15 per cent and still remain profitable.12

And so they did. Walmart began adding food to the mix in the late 1980s, as discussed previously, and by 2001 they had taken the throne to become the largest seller of food in the United States.13 It is amazing to think that Walmart achieved all of this in a space of just over a decade, quite a remarkable feat considering how long the existing competition had been around. A&P, once the United States’ biggest supermarket, dates back to 1859.14 In fact, it has been referred to as the ‘Walmart before Walmart’, having invented the modern-day supermarket, launching Women’s Day magazine, sponsoring A&P radio hour and owning the world’s best-selling coffee brand at one time. In the 1930s, A&P had approximately 16,000 stores and more than $1 billion in revenue.15 Kroger – the largest traditional supermarket chain today – has been trading since 1883 when Barney Kroger opened his very first grocery store in downtown Cincinnati.16 It would be over 100 years before Walmart would even consider getting into the food business, yet once it did there would be no turning back.

Today, Walmart commands a 15 per cent market share of the US food sector, which may sound low compared to Tesco or Carrefour’s share in their domestic markets, but it’s important to remember that the US grocery sector is vast and still quite regional despite the bouts of consolidation that have occurred over the past few decades. In fact, Walmart’s 15 per cent share translates to over $100 billion of sales (food, consumables and HBC17) and, in some areas, often lower-income mid-sized cities, Walmart plays a much more dominant role with more than 30 per cent market share in certain cases.18

It’s important, however, to remember that not everything Walmart touches turns to gold. Hypermart, the large-box concept that preceded Walmart Supercenter as the company’s foray into hypermarket retailing, was a total flop. In an unusual twist, a concept that originated in Europe was deemed too big for US shoppers. With over 200,000 sq. ft, Hypermarts aimed to combine everything under one roof – groceries, clothing, electronics, banking, photo-processing etc. A ‘mall without walls’ as described by Walmart.

Since its launch in the early 1960s, the hypermarket concept had been a hit across the Atlantic; however, circumstances were very different in the US retail market. Shopping malls and big discount stores were already well established. The market was very competitive, with category specialists such as Toys ‘R’ Us dominating the non-food arena and supermarkets winning on location. Although some US retailers were finding success with this larger format – namely Meijer and Fred Meyer – Walmart found it too difficult to manage a store the size of four football fields (during Carrefour’s brief stint in the United States, employees in its 330,000 sq. ft Philadelphia store wore roller skates to navigate the aisles).19 Concerns over both profitability and manageability led to Hypermart’s discontinuation in 1990 in favour of the smaller, more profitable Supercenter concept.20 Throughout its history, Walmart also experimented with other formats such as Dot Discount Drug Stores – a chain of drugstores in Kansas, Missouri and Iowa which was sold in 1990;21 Save-Co Home Improvement (divested in the 1970s);22 and Helen’s Arts and Crafts Store which was sold off to the United States’ largest crafts retailer, Michael’s:23

Supercenter conversions have fuelled Walmart’s phenomenal growth in the food retailing sector. Aside from acquisition, how else could a retailer go from zero to 3,000 stores totalling over a half billion sq. ft, the equivalent of four times its closest competitor, in the space of just over a decade?24 Walmart’s existing fleet of general merchandise discount stores provided the retailer with a vast network to convert to the more profitable Supercenter format. Adding groceries to existing stores – versus organic expansion with a new format – was a relatively straightforward, non-capital-intensive project that enabled Walmart to drive shopper frequency and increase basket size.

More than cost cuts or technology – or even Wall Street schmoozing – it’s the Supercenters that are likely to carry Walmart into the next century.

(Fortune, 1998)25

During the 1990s, Walmart converted nearly 600 discount stores to the Supercenter concept as it looked to make its rapid incursion into the $425 billion US grocery industry.26 At the time, the hugely fragmented supermarket sector was almost three times the size of the discount segment, where Walmart was one of three retailers that, when combined, controlled over 80 per cent of the market. In the grocery sector, however, the top five retailers accounted for less than a quarter of the market.27 As recent as the early 1990s, the leading supermarket chains still included companies like A&P (filed for Chapter 11 in 2010), Winn-Dixie (filed for Chapter 11 in 2005) and American Stores (merged with Albertsons, now part of SuperValu, in 1998). Walmart certainly ignited change in the industry.

The format was such a success that during the next decade (2000s), Walmart converted more than twice as many (over 1,200) discount stores to the Supercenter concept.28 The weighted square-footage average of a big-box Walmart store (ie including discount stores and Supercenters) grew from 125,000 sq. ft in 2000 to 169,000 sq. ft in 2010 as Walmart embarked on the most significant food-retailing conversion process in US history. And Walmart wasn’t alone: supermarkets were also getting bigger. In fact, the Food Marketing Institute estimates that over the past 15 years, the average US supermarket has grown by 24 per cent to 46,000 sq. ft.29

But going back to Walmart Supercenters, these stores introduced low prices and broad ranges to rural or low-income areas. The value-led, no-frills concept exposed the high cost structure of traditional supermarkets, particularly when it came to the always touchy subject of labour relations. Walmart employs over 2 million associates worldwide, 1.4 million of whom are in the United States. Not only is Walmart one of the largest private employers in the United States, but it is also the largest in Mexico and one of the largest in Canada. In the United States, and to a slightly lesser extent Canada, the retailer has faced years of backlash for its anti-union stance. This, of course, has contributed to Walmart’s ability to undercut traditional supermarkets on price, given that labour – primarily unionized – is typically the largest single expense item for retailers.

It is a classic case of Walmart doing what it does best – getting rid of the middleman, stripping out inefficiencies and passing the savings on to customers in the form of lower prices. As discussed in the previous chapters, its scale, lean cost structure and EDLP policy makes it impossible for the majority of supermarkets to compete with Walmart on price. Those that aim to take Walmart head on often find themselves digging an early grave, and as witnessed in markets such as Canada, retailers with a high non-food share will typically be more exposed to the Walmart threat. Therefore a far healthier approach is to play to Walmart’s weaknesses, which up until recently have been product quality, store environment and convenience:

Supercenters effectively serve a large trade area, but we think there may be some business that we are not getting purely because they may not be as close to the customer or convenient for small shopping trips.

(David Glass, 1998)

Today, the Supercenter concept remains the backbone of Walmart’s business, both at home and abroad, with Planet Retail estimating that approximately three-quarters of Walmart’s global sales were generated through this format in 2010. Looking ahead, emerging economies are ripe for large-format development (ie Brazil, South Africa, China and India, foreign direct investment (FDI) permitting), which will enable Walmart to drive growth – a proven formula abroad (albeit with some local tweaks and infrastructure challenges as we’ll discuss in the next chapter). However, for the American Supercenter, time is quickly running out.

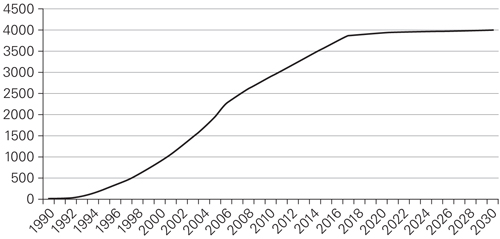

We expect Walmart to have completed the conversion of its discount stores to Supercenters by 2020 (see Figure 10.1). These conversions have fuelled Supercenter growth since inception, yet over the next decade there will only be a few hundred opportunities for conversions.30 In fact, 2009 was the first year in Walmart’s history that it did not open any new discount stores.31 It is a format nearing extinction and once it does, organic expansion with the Supercenter format is also expected to dry up for three reasons.

FIGURE 10.1 Number of US Walmart Supercenters, 1990–2030f

SOURCE: Company reports; Authors’ forecasts

Firstly: saturation – Walmart already holds a market-leading position in the vast majority of US trading regions. There are Supercenters in every US state except for Hawaii and Vermont.32 Secondly: population growth in the United States will not be fast enough to sustain a significant number of new Supercenter openings: the US population is expected to increase by less than 1 per cent on a compounded annual basis over the next decade.33 And thirdly: consumers are rapidly shifting their shopping patterns owing to technological and societal changes. The growth of e-commerce alone will result in a degree of cannibalization of bricks-and-mortar stores, all the more incentive to slow Supercenter growth. The bottom line is that Walmart is coming to an end of an era. It is reaching saturation with a format upon which the company has built its success. We expect Walmart Supercenters to hit saturation in the US market at approximately the 4,000 mark, leaving one last decade of meaningful growth with the format.

But Walmart has never been one to rest on its laurels, so the world’s largest company is now on an ambitious path to discover new avenues of growth. Supercenters will continue to play a key role in Walmart’s future, but it must also explore the two most obvious untapped segments in its domestic market – small-box stores and e-commerce.

In an exclusive interview with the authors, Bill Simon, President and CEO of Walmart US, commented: ‘We believe there is tremendous opportunity for growth here in the US. The growth will come from additional penetration into more metropolitan markets, as well as from new formats and stronger integration with the online business. We will move toward a three-format portfolio, which will drive expansion to urban markets and small towns, as well as fill in gaps in existing markets.’

The final frontier: getting bigger by going small

You can’t just keep doing what works one time. Everything around you is changing. To succeed, stay out in front of change.

(SAM WALTON)34

When most people think of Walmart, the image of a 185,000 sq. ft Supercenter looming over US highways is typically what comes to mind: big stores in the ‘burbs with shelves piled high with cheap merchandise. This is how Walmart has established itself in the United States. In fact, an old annual report proudly states that ‘since its beginning, the Walmart concept was based on the theory that a quality discount store could open profitably, and even thrive, in a small community’. They’ve done this – in fact, they mastered it – but the question today is can they survive in a ‘big community’?35

The Walmart of the future will feature a whole new dimension – the 15,000 sq. ft store. A fraction of the size of a Supercenter, the Walmart Express concept was rolled out in 2011 and marks a whole new era of retailing for the Bentonville giant. The stores feature between 11,000 and 12,000 SKUs, with grocery items accounting for around 70 per cent of the assortment.36 The store’s entire range may be equivalent to that of a small department in a Supercenter, but it’s important to point out that it is catering to three unique trips – quick, fill-in and stock-up. Despite its edited assortment, Walmart Express still offers three times the number of products found in a typical Fresh & Easy outlet (more on that to follow).

The store concept was developed in less than six months. To put that into perspective, Walmart’s previous new-store format took three years to complete.37 However, it’s no secret that Walmart was losing market share to the dollar stores – and losing it quickly. Walmart Express therefore can be seen as a defensive mechanism towards both the rise in dollar stores and alternative food formats, yet it is also very much an offensive move as it will grant Walmart a better chance of tapping into underpenetrated urban areas in the United States.

Although Walmart will exert a fair degree of caution with regard to a broad-scale roll-out, it is fair to say that there could be hundreds of these small-format stores in operation within just a few years. While price continues to play a key role with this new condensed format, quality and convenience are also vital ingredients, requiring a major strategic shift for the world’s largest retailer.

It’s not just the micro stores that will help Walmart reach untapped consumer markets. Walmart’s three-format portfolio, unveiled in late 2010, includes Supercenters and small formats (under 30,000 sq. ft) as discussed but also a mid-sized store ranging from 30,000 to 60,000 sq. ft.38 This mid-sized store, very much in line with the size of an average US supermarket trades as Walmart Market and Walmart Neighborhood Market, a move signifying that Walmart is looking to emulate the single-brand, multi-channel approach which has been so successful for European retailers such as Tesco. It’s about extending the Walmart brand, realizing synergies and ensuring a consistent shopping experience across multiple formats. Averaging 42,000 sq. ft, Walmart Market will work in tandem with Express to penetrate those difficult urban settings where a 185,000 sq. ft store would be deemed impossible, too expensive or irrelevant.

In an exclusive interview with the authors, Anthony Hucker, Vice President of Strategy and Business Development at Walmart US, commented: ‘Supercenters are still our highest ROI-generating vehicle, so we start with the largest box we can, according to what’s appropriate in the particular trade area, and use a sequencing technique which, simply put, goes from large, to medium, to small which takes into account the politics permitting and economics that either enable or inhibit that particular opportunity.’

If we look back to just five years ago, Walmart would have been in no position to launch its small-format assault. Despite the fact that Walmart Market (then Neighborhood Market) has been trading since the late 1990s, it was never a priority for the company given their focus on more profitable growth through Supercenter conversions. Fresh, high-quality food is a key ingredient for small-format stores, an area where Walmart has traditionally struggled. However, as discussed in the private label chapter, the overhaul of the Great Value line and other improvements in grocery have helped to reposition Walmart’s quality perception, instilling trust among consumers. Equally, Walmart today is able to use its smaller stores as distribution points for online orders, making the store size and lack of non-food assortment less of an issue than it would have been just five years ago when the notion of ordering online and picking up in-store was virtually non-existent:

Where we weren’t five years ago is a place where we were willing to put small stores into urban areas. What we have to do is deliver the brand to customers in those markets, and the brand can come in a small format.

(Bill Simon, 2011)39

Walmart may have made its name with big stores, but this isn’t to say that they hadn’t considered small-box in the past. In the late 1980s, Walmart tested a handful of convenience stores positioned next to existing Supercenters and Sam’s Clubs. However, that only lasted a few years before Walmart sold the nine stores to Conoco.40 A decade on in the late 1990s, Walmart tested yet another concept, this time aimed at taking the grocers head on. The 40,000 sq. ft stores were tentatively billed as Wal-Mart Food & Drug Express,41 not far from the branding Walmart has gone for in its most recent drive for small-box. In fact, looking back at Walmart under David Glass’s leadership, we see that certain strategic initiatives 15 years ago bear a striking resemblance to the Walmart of 2012 – primarily the drive to tap into urban settings with a food format. Wal-Mart Food & Drug Express never made it to launch; instead the stores opened as Neighborhood Market. At the time of launch, the Wall Street Journal wrote: ‘The new stores could let Walmart add stores in small towns and urban markets that aren’t right for the large Supercenters… The smaller size could appeal to customers who don’t want the hassle of braving the mammoth parking lots and extensive aisles of Supercenters.’42 So why, since its launch, has the company opened an average of just 13 Walmart Market stores per year?43

The answer is simple: it had its hands full opening nearly 200 Supercenters annually (from 1998 to 2010; includes conversions). It’s clear to see where Walmart’s priorities were. Supercenters are inherently more profitable owing to their size and non-food assortment, but as we know by now, that growth potential is nearing an end, which means that Walmart has no choice but to make one last push for smaller stores.

As we hope we have demonstrated so far, Walmart is not a believer in complacency. Just as they recognized the potential in European hypermarkets – albeit with a few tweaks – the same can be said for their smaller stores. In the United States, the average supermarket measures 46,000 sq. ft.44 There are very few operators who have cracked the 20,000 sq. ft range and below and for good reasons. Firstly, there is little incentive to go small when real estate is cheap and land is plentiful. The same cannot be said in Western Europe where high-rent, densely populated and saturated markets such as the UK have led all of the major supermarkets to launch smaller formats (including Walmart’s own Asda which acquired the Netto discount chain in 2010). Secondly, going small is trickier than it sounds. Getting the assortment right is vital. Since shoppers typically won’t be able to complete a full basket in this setting, getting the right brands, SKUs and categories is a must. It has to be relevant and local to be successful and this is where access to shopper data comes into play.

Generally, these scaled-down stores should feature a heavy amount of private label items in order to push profits (in urban areas in particular the cost of doing business is greater, which puts pressure on margins). Walmart Express is arguably too brand-led in its current state; however, given the retailer’s failures with regard to rationalizing its SKU base, going heavier on brands versus private label is a much safer bet.

Labour, as discussed, is one of the largest expenses for retailers, and therefore achieving a cost-effective labour model is vital in a smaller box. Although there are, of course, fewer staff per store in a Walmart Express, for example, it’s important to bear in mind that these stores must be replenished more frequently owing to their smaller size – which inevitably adds cost into the business. ‘The EDLC model is the only way to operate these smaller stores’, Mr Hucker told us. ‘Getting the store economics right is crucial in order for this format to succeed.’ One of the largest elements of labour is the front-end (and this therefore explains why Tesco’s Fresh & Easy went for self-checkouts only). It is a difficult balance of managing costs and customer service.

Shopper data and demand forecasting are key in order to keep stock at the right levels. Finally, these stores must be located within relatively close proximity to larger Supercenters in order to achieve economies in the supply chain (which enables Walmart to offer low prices in a smaller-format setting). As such, there is certainly a degree of self-cannibalization. This has been a problem in China in particular where poor infrastructure has put even greater pressure on retailers to co-locate their stores, particularly for Walmart which must achieve EDLC in order to invest in EDLP. It’s no coincidence that the company’s first compact hypermarket in Zhangshu is located near to six Walmart Supercenters, and its Smart Choice discount stores are also within close proximity to larger formats.

This all sounds like quite a hassle, especially when you consider that it would take 500 smaller stores to deliver the same benefit as 10 superstores, as former Asda CEO Andy Bond pointed out. ‘Convenience stores are not the cake, they are the icing’, he said back in 2007.45 However, the cake can’t get much bigger in markets like the UK and the United States where, as we have discussed, Supercenter growth is nearing saturation. Time to focus on the icing.

In the United States, small-box development was spurred on in 2007 when Britain’s Tesco, the world’s third-largest food retailer, entered the market with a completely new concept: Fresh & Easy. Tesco broke all the rules of US food retailing (something that hasn’t gone unnoticed judging by its financial results – Tesco is unlikely to turn a profit in the United States until 2013).46 Everything about the concept was different at the time of launch. At 10,000 sq. ft, Fresh & Easy is around a quarter of the size of a traditional supermarket. With 4,000 SKUs, its breadth of product choice is similar to limited assortment retailers such as Costco. Half the offering is private label (twice as much as found in a typical supermarket). None of these factors were deal breakers. In fact, there have been similar alternative formats that have successfully struck a chord with US shoppers. Trader Joe’s, the limited assortment, mainly private label supermarket chain owned by Germany’s Aldi, has a cult-like following in the United States. With sales per square foot of $1,750, store productivity levels are twice that of Whole Foods Market.47

So what went wrong at Fresh & Easy? Well, some of it simply comes down to bad timing. Tesco entered the United States months before the economic crisis struck. The Southwest, where Fresh & Easy set up shop, was one of the hardest-hit regions during the recession. High home-foreclosure rates and unemployment levels actually led to negative population growth – many of America’s boom cities on the West Coast, once growing by 6–7 per cent, were suddenly declining by 10 per cent year-on-year.48 In fact, about a quarter of US foreclosures in 2008 were derived from just eight counties in Arizona, California, Nevada (all three of which are on Fresh & Easy turf) and Florida.49

At the same time, Tesco had set up the infrastructure to service thousands of stores (former CEO Terry Leahy had originally envisioned 10,000 outlets50), but the economic gloom stunted store expansion plans and after three years of trading fewer than 200 stores were in operation.51 At the time of writing, losses plus initial investment amounted to roughly £1 billion.52

While some of Tesco’s misfortune has been out of its control, there have also been some fundamental problems with its store concept. The efficiency-driven, sterile store environment initially failed to connect with US shoppers. They may have been used to shelf-ready packaging and products displayed on pallets (both of which are reminiscent of the warehouse club channel, which is hugely popular among US families), but shoppers weren’t ready for pre-packed fruit and vegetables or a self-checkout-only option. There is no counter service, which adds to the clinical feel, and, unlike the Brits, US consumers have a strong preference for freshly cut deli meats.

The stores did not initially accept loyalty cards, despite the fact that Tesco operates what is arguably the most successful loyalty scheme in the world. This held Tesco back, not only from rewarding shoppers for their custom but also from gathering the essential shopper data that have enabled the retailer to tailor its merchandising and marketing efforts in 12 other markets around the globe. In the United States, dunnhumby is a joint venture with Kroger, which initially put Fresh & Easy in an awkward and limiting position. Sharing a shopper database with the competition was unlikely ever to happen (although Fresh & Easy finally managed to launch a loyalty scheme, using dunnhumby UK, in 2011). In any case, despite Tesco’s initial fumbles and greater concerns over the long-term viability of Fresh & Easy, it has certainly been successful in one thing – igniting change in the industry.

Since Fresh & Easy debuted on US soil, there has been a proliferation of small-format launches across the nation. Walmart itself rolled out its first new format in a decade – Marketside, the four-store, 15,000 sq. ft concept debuted in the Phoenix area a year after Fresh & Easy’s launch. Despite always referring to Marketside as a pilot, Walmart said from the start that the concept could evolve to up to 1,500 stores with annual sales of more than $10 billion.53 Things clearly didn’t go to plan; however, it sparked similar reactions by other retailers looking to experiment with scaled-down versions of their larger stores, including Target (CityTarget), Ahold (Giant), Safeway (Vons), Price Chopper, Hy-Vee, Schnucks, SuperValu and Giant Eagle.

Although Marketside failed to move beyond its pilot phase, it served as a very valuable experiment for Walmart in terms of both operating a store of that size (hence the Walmart Express launch three years later) and improving its grocery offering. Also, the Marketside private label is now offered across Walmart’s Supercenters, giving it far greater visibility than when it was a range limited to a handful of stores in Arizona, and helping to improve Walmart’s quality perception on freshly prepared foods.

In another move towards diversification, Walmart launched its first Hispanic format in 2009. Converting a 39,000 sq. ft Neighborhood Market store, the retailer’s first Supermercado de Walmart concept opened its doors in Houston, Texas in April that year. The 13,000 products on offer included a wide assortment of national brands from the United States and Mexico, fresh tropical fruits and vegetables, and a bakery offering more than 40 traditional sweet breads and fresh corn tortillas. Speciality meats included milanesa, diezmillo, fajitas, chuleta de cerdo, carnes marinadas and arrachera, all targeted towards the local Hispanic customer.54 Walmart was able to draw on its expertise in Latin America, Mexico in particular, in order to ensure local relevance to Houston’s vast Hispanic population.

You have to applaud Walmart for moving away from one size fits all in an attempt to cater to America’s fastest-growing consumer group. In fact, by 2050 the country’s Hispanic population is expected to triple to 132.8 million, at which point nearly one in three US residents will be Hispanic. Although places like Texas and California are already majority-minority states, by 2042 the entire United States is expected to transition to a majority-minority country.55 Clearly, retailers and manufacturers need to be thinking about how to better serve this increasingly important demographic.

Unfortunately, however, like Marketside, Supermercado de Walmart is unlikely ever to move beyond the experimental phase. The concept was arguably too specialized, catering more towards Latin-American-born consumers versus the millions of second- and third-generation Hispanics in the United States. The vast majority of the latter group would surely prefer a traditional US store, perhaps tailored to offer more localized ranges, but not an entire shopping experience similar to what you would find south of the border:

We have lots of learnings around the world from Walmart in small formats. Our group in Mexico and Central America and Latin America operates small formats very well and very profitably, and we are going to beg, borrow, steal and learn from them as quickly as we can, because it is important for our urban strategy.

(Bill Simon)

Yet, as demonstrated by new concepts such as Marketside and Supermercado, Walmart as an organization is becoming far more versatile with regard to its formats. As we’ll discuss in the next chapter, it’s becoming less about broadcasting plans from a Bentonville base and increasingly a two-way conversation with international operations, particularly when it comes to format development. This is true of cash & carries where Walmart has exported learnings from Brazil to India. ‘… We’re flexible, and we can look at a market and think about where we put a specific format so that we can grow the overall share and increase profitability by being more than one dimensional as it relates to formats’, Doug McMillon said in 2010.56

Compact hypermarkets, which are about half the size of a Walmart Supercenter but generate similar returns on investment, have been copied and pasted from Mexico to China, where, as mentioned previously, Walmart opened its first compact hypermarket in 2010.57 The UK team is helping to share their e-commerce expertise with the rest of Walmart’s operations, particularly in the United States where the company began testing an online grocery offering in 2011.58 And going back to its next era of small-box retailing in the United States, Walmart has been heavily inspired by the success of its Latin American bodegas. Walmart Express may have been ‘created with a US lens’, as Mr Hucker puts it, but it most certainly draws on the likes of Todo Dia in Brazil, Bodega Aurerra Express in Mexico and Changomas in Argentina. ‘We run small formats all over the world,’ said Bill Simon, ‘and these small boxes are among the most profitable businesses that these countries run.’59

Grandma, the Manhattanite and fraternity boys

Smaller stores will play a pivotal role in the next phase of retail evolution in the United States. By 2050, one in five Americans will be over the age of 65. The United States’ elderly population is expected to more than double (based on 2010) to 89 million people.60 That is almost the equivalent of the size of Germany today.61 Retailers are right to begin thinking about how to cater to this cash-rich emerging demographic. These shoppers will certainly prefer proximity over bulk buying.

At the same time, US consumers are increasingly leading fast-paced lifestyles – there are a rising number of single households as well as time-sensitive working moms, both of which are factors that bode well for a small-box format. The acceleration of Walmart Market and Express will allow the retailer to continue to fill in markets where they already have a Supercenter presence, such as Dallas and Las Vegas, as well as potentially enter new urban areas such as New York and Los Angeles.

Reaching the untapped and potentially extremely lucrative urban shopper would be Walmart’s final jackpot. The top 15 metro areas in the United States represent a huge multi-billion opportunity for the retailer compared to the market share they have in the rural United States.62 ‘These cities could almost be viewed as countries in and of their own right, when we size the prize of food deserts and customers either being badly served or underserved’, Mr Hucker told us.

Most people would think that our base in America is probably people who’ve historically self-identified themselves as conservative voters. So now we only have one segment left – people who self-identify themselves as liberals.

(Leslie Dach, Walmart’s Executive Vice President of Corporate Affairs and Government Relations, 2010 (on Walmart’s urban strategy))63

Now Walmart has had a notoriously difficult time gaining approval from city councils, mainly owing to strong union opposition, who fear Walmart’s arrival will result in the demise of neighbourhood shops, job losses, the erosion of downtown districts and continued retail homogeneity. And it’s not only cities – it can take up to seven years to open a Supercenter in the state of California.64 Walmart too has had its fair share of frustrations with urban development, so much so that former CEO Lee Scott infamously said that New York City was simply not ‘worth the effort’. He told New York Times reporters in 2007: ‘I don’t care if we are ever here.’65 Not only was Walmart facing fierce opposition from labour unions but it also found that doing business in New York came with a hefty price tag. Despite its mammoth buying power, even Walmart finds it more challenging to buffer its profit margins in an urban setting, owing to higher property costs. Pricing needs to be consistent with its larger stores so that Walmart can stick with its golden rule of selling national brands cheaper than competitors do. This will be one of the biggest challenges for Walmart in urban areas given that real-estate costs can be more than double that of their rural locations ($40–50/sq. ft versus $20/sq. ft):66

Every Day Low Prices can happen in 15,000 square feet.

(Bill Simon, 2011)67

But Walmart hasn’t given up on the city that never sleeps, and recently the company has drastically shifted gears in a final bid to tap into the Manhattanite’s wallet. Walmartnyc.com was launched in 2011 as a way to raise awareness of the benefits that Walmart can bring to a city of over 8 million so-called underserved consumers. According to the retailer, nearly three-quarters of New Yorkers want Walmart to open. City residents are already spending nearly $200 million at its stores outside the five boroughs, which amounts to enough sales to support three Supercenters. Despite, or indeed because of, a lack of physical store presence, New York City is Walmart’s largest US market for its online division.68,69 It would be the retailer’s last and largest domestic prize.

But it’s not just about the lucrative New York market. Mr Simon told the authors that he believes there are ‘plenty of opportunities’ to serve more consumers in the United States. ‘This is especially true in places like Chicago and Washington, DC with large populations of residents who are underserved, need convenient access to fresh, affordable food, and live in communities that are in need of new jobs and economic growth.’

More than 23 million US consumers, including 6 million children, currently lack access to supermarkets and fresh foods, living in so-called food deserts. As part of Michelle Obama’s initiative to bring healthy foods to these impoverished neighbourhoods, Walmart, along with SuperValu and Walgreens, has committed to expanding in these underserved areas. By 2016, Walmart will open up to 300 stores in such areas, while SuperValu has committed to opening a similar number. Meanwhile, at least 1,000 Walgreens stores will open or be converted to include food over the next several years. Currently, almost half Walgreens stores are located in areas that do not have easy access to fresh food.70

Walmart has come a long way in cities like Washington, DC, and Chicago thanks to improvements in food quality, labour relations, healthier food strategy and environmental initiatives which have helped to improve its reputation among both consumers and city councils. Walmart has since won approval to open its first stores in Washington, DC, which will debut in late 2012, bringing fresh groceries, a full-service pharmacy and a variety of general merchandise to areas that have traditionally been underrepresented by chain retailers. Once again, Walmart has been the primary beneficiary of a weak US economy. With high levels of unemployment and many urban consumers lacking access to fresh, low-priced groceries, the same local governments that previously shunned Walmart are now having a change of heart. In Washington, DC, Walmart will create 1,200 jobs.71 In Chicago, where Walmart has faced severe public opposition for years, it won approval in 2011 to open six stores which will create 10,000 jobs by 2015.

‘When I met with Walmart [in 2010], I encouraged them to take an approach that addressed the needs of the urban shopper if they truly wanted to make a difference in our underserved neighbourhoods’, said Chicago’s Mayor Richard Daley. The six Chicago stores include Supercenters, Express stores and Walmart Markets.72 This flexible, multi-channel approach is how Walmart will crack America’s cities.

Meanwhile, there is one other untapped consumer segment that has caught the Bentonville giant’s eye. This group has historically gone unnoticed by US retailers given their general lack of purchasing power and consequent love for Ramen noodles and Kraft Mac & Cheese – the American college student. As part of its broader small-format strategy, Walmart opened its first Walmart on Campus store in 2011. Like most pilot formats, the campus store was tested close to home at the University of Arkansas. Replacing a university-run pharmacy, the 3,500 sq. ft Walmart on Campus store is the retailer’s smallest to date, featuring a full-service pharmacy, groceries and a selection of general merchandise. The authors visited the store soon after opening and were impressed once again with Walmart’s growing flexibility with regard to store layout and merchandising – this is quite possibly the only Walmart store with entire endcaps devoted to Ramen noodles. Despite the fact that college kids may not be the most cash-rich group to target, there are more than 20 million nationwide73 – many of whom are currently limited with regard to retail operations on campus – not to mention the staff, faculty, visitors and community members who will also benefit from a Walmart opening. We view this as a fantastic life-stage opportunity to connect with future consumers. At the time of writing, the concept was exceeding company expectations and there has been much interest from other colleges and universities. Watch this space.

The kings of convenience: US drugstores

We are going to be adding hundreds of these in the coming years and maybe even more depending on how they work out.

(BILL SIMON ON SMALLER FORMATS IN THE UNITED STATES, 2011)74

Given Walmart’s ambitious growth plans with a smaller format, the authors can’t help but wonder if an acquisition could be on the cards. Although there are cases against it (Walmart has traditionally opted for organic over acquisitive growth in the United States, small-box development could occur quickly enough on an organic basis and, of course, there would likely be regulatory barriers), an acquisition would give Walmart a foothold in the convenience market essentially overnight. And they certainly have the cash.

So who might they consider? Well, as we said earlier, not many traditional supermarkets have cracked the 20,000 sq. ft and under range, so more likely than not Walmart would be looking at a drug or dollar store primarily from a real-estate perspective. The main US drugstore chains – Walgreens, CVS and Rite Aid – have an astonishing reach with a combined 20,000 stores.75 In fact, nearly three-quarters of the US population live within five miles of a Walgreens and 6 million shoppers visit their stores on a daily basis.76 Powerful stuff.

The drugstores are now looking to capitalize on their advantageous real estate by adding more fresh foods to the mix. For example, Walgreens has added nearly 800 new food items, including fresh fruits and vegetables, frozen meats and fish, pasta, rice, beans, eggs and whole-grain cereals, to some of its stores.77 CVS is in the process of adding food to about 300 urban stores in Boston, New York, Washington, Detroit and Philadelphia. One-fifth of its 7,000 stores could eventually be reconfigured.78 Rite Aid is also looking to get in on the action, having partnered with SuperValu’s Save-A-Lot discount chain to launch a hybrid format combining grocery and drug (which, call us crazy, almost sounds like… a supermarket). The drugstores have also been busy revamping their private label assortment so as to grab a larger share of the grocery pie more profitably while at the same time driving shopper loyalty. In 2011, Walgreens launched the Nice! range while CVS debuted its Just the Basics brand.

Although the drugstore channel on the whole is smaller than traditional supermarkets, food sales are growing far more rapidly in the drugstore channel. This is a clear indication that their strategies are paying off and that there is genuine demand for low-priced, quality foods in a convenient setting. According to SymphonyIRI, in the 52 weeks to June 2011, drugstores experienced a 6.9 per cent increase in beer sales to $1.1 billion, versus supermarket growth of just 1 per cent in the category to $8.4 billion. Frozen dinners is another booming category: the drugstores saw a 15.9 per cent increase in sales while supermarkets recorded a mere 0.09 per cent rise. In some categories, such as dog food, the drugstores have grown sales by close to 20 per cent while supermarkets have actually lost share:79

Going small prevents us from losing the milk, bread and eggs trip to the drugstores… but we’re still a long way from perfecting this.

(Walmart executive)

The drugstores win on convenience. They win on shopper frequency, particularly when catering to shoppers with repeat prescriptions, of which there will be many more in the coming decade. However, there is one area where they let shoppers down – price. Because groceries are not the drugstores’ core offering, they tend to buy and store food less efficiently than supermarkets, which is noticeably reflected in their prices. In Brooklyn, for example, a Siggi’s yogurt at a Duane Reade costs $3.19, but can be purchased for just $2.75 at a nearby corner store. ‘There is a cost of convenience, because we are on some of the best corners in America’, said Walgreens’ chief merchandising officer, Bryan Pugh.80 We can think of one retailer in particular that is ready to challenge that statement.

That is not to say that Walmart shouldn’t be worried, particularly given the projected growth in over-65s as discussed earlier in the chapter. A one-stop shop – food and pharmacy – in a small, convenient setting has a long, healthy future in store. So we believe that Walmart could look to make a drugstore acquisition as part of its smaller-format strategy. Not only would it enable the company to stamp out the growing grocery business in existing drugstore chains, but Walmart would also benefit from the expertise of a smaller chain as they look to capitalize on the United States’ ageing consumer base. To our mind, based on current valuations and distribution of stores, Rite Aid would be the ideal candidate.

An acquisition would also enable Walmart to battle another thorn in its side – the dollar stores. Currently worth $45 billion, the US discount sector is expected to more than double in the next decade to reach $100 billion, according to Planet Retail. And as much as it may pain Walmart to admit it, the dollar stores in particular have been eating into its market share over the past several years.

Kantar Retail’s shopping behaviour analysis, ShopperScape, indicates that many shoppers have defected from Walmart to conventional supermarkets and Target. However, parsing the data by income market shows that less affluent shoppers are most likely to divert trips to dollar stores – evidence that leakage to dollar stores has the potential to derail Walmart’s efforts to reassert its EDLP price leadership position among a core shopper segment.

As discussed in the pricing chapter, taking its eye off EDLP was a major opportunity for the dollar stores to flaunt their pricing credentials. And while these stores used to cater primarily to low- and fixed-income groups, today they are seeing more affluent, bargain-seeking shoppers coming through their doors. Consequently, average spend per store has increased. The dollar stores are now making major improvements in terms of store design, merchandising (like the drugstores, they are adding more groceries to the mix) and, crucially, improvements in location. Owing to the high number of property vacancies and sudden demand for value among consumers, these discount-led stores have been able to get into higher-traffic and higher-income sites which, as a result, has helped to raise their awareness among new consumer groups.

As discussed earlier, the dollar stores and Walmart have traditionally not gone head to head. Given the small size of a typical dollar store, merchandising assortment is extremely limited, which means that shoppers can’t complete a full weekly basket. Yet, given the strong overlap in shopper demographics, the dollar stores benefit from the amount of traffic generated by Walmart. ‘You can’t out-Walmart Walmart’, Family Dollar CEO Howard Levine said in 2011. ‘The dollar stores are not going after the same trip Walmart is going after. We’re going after the fill-in trip. We live off the crumbs they leave us.’81 The roll-out of Walmart Express will surely change Levine’s view about sharing a similar trip. Express will enable Walmart to reach those rural consumers in a new, convenient setting. It is not only fighting back on the value front (with comparable Supercenter prices) but it differentiates from the dollar stores with in-store pharmacies, cheque cashing and other financial services, and its site-to-store initiative.

Based on our analytical modelling, we believe we still have approximately 12,000 opportunities for new stores.

(Richard Dreiling, CEO of Dollar General)82

However, up until now, living off the crumbs has not been a bad strategy, given the high growth levels we have seen from this sector over the past decade. Dollar General, the largest of the bunch with roughly 10,000 stores, has opened an average of 450 stores annually over the past decade.83 Growth has been phenomenal and there are certainly no signs of slowing down: at the end of 2010, Dollar General told investors that there is room for an additional 12,000 new stores, of which 8,000 will be in existing markets.84 Private equity ownership has fuelled Dollar General’s growth, and this is a trend we continue to see throughout the sector.

The addition of perishable groceries, a clear pricing model, rapid expansion plans, store remodels and better sites are all reasons why the dollar stores are keeping Walmart up at night. During the recession, while Walmart was reporting quarter after quarter of negative comparable store sales growth, Dollar General was posting high single-digit increases. With little sign of this sector slowing down, Walmart will have to get serious about going small.

A new retail world is evolving and Walmart is ready to embrace it.

(EDUARDO CASTRO-WRIGHT, 2011)85

Just as small stores were never a priority in the past, e-commerce was also a back-burner topic for Walmart for many years. Its stores may attract 10.5 billion consumers around the globe each year, but in cyberspace Walmart attracts roughly one-tenth of that figure.86 In terms of revenues, e-commerce accounts for a mere 2 per cent of Walmart’s total sales, despite the retailer’s 15+ years’ presence on the world wide web.87 So why have they been so late to the game?

As discussed earlier in the chapter, for the past decade the company was – justifiably to a certain degree – more concerned with growing its Supercenter estate during this time. Supercenters were highly profitable, in demand, and far less risky than growing a dotcom business. ‘The internet has some very interesting aspects and will definitely serve a growing market as we move into the 21st century’, Chairman Rob Walton noted back in 1999. ‘However, very few, if any, internet retailers have made a profit, and issues like the cost of delivery, merchandise returns and data security all have to be resolved before this business model is validated.’88

Internet retailing used to be confined to buying books and music from a desktop computer. Today, smartphones let us customize our grocery list while waiting for a bus. Today, thanks to augmented reality, clothes can be tried on virtually before placing an order. Today, we don’t have to wait in for a delivery – we can order online and pick up at a local store at our convenience. By 2015, the US e-commerce market is expected to be worth $279 billion, a statistic that Walmart can no longer ignore.89

But it’s not just about transacting online – the internet has truly empowered consumers. Today, we are armed with product and pricing information. We thrive off transparency. We use social media to interact with retailers and brands (and, crucially, to be heard when something goes wrong). We use the internet to share deals and recommend products. We find both value and excitement through flash sales and group buying. E-commerce today is instant, engaging and relevant. And Walmart has been missing out.

‘It’s fair to say that up until about a year ago, when Mike Duke defined what we call the next generation of Walmart as a major initiative for the company, probably we were not as keenly devoted to creating the kind of shopping experiences across all channels as we are doing today’, said Eduardo Castro-Wright,90 who took the helm of the company’s online division in June 2010.

Walmart has been slow to jump on the digital bandwagon, in part because its core shoppers have not been the earliest adopters when it comes to new technologies. In 2007, Walmart closed down its movie and TV show download service with Hewlett-Packard just 10 months after launch.91 Three years earlier, Walmart launched a digital music download service in a bid to catch up to iTunes and Amazon’s MP3 store, but that too failed to resonate with shoppers, and was eventually shut down in 2011.92

A survey by Gallup showed that in 2005, households with annual income of $100,000 or more were three times as likely to buy online compared to households with income under $35,000 and 33 per cent more likely than households with income of $75,000–$100,000.93 Back in 2005, lower-income households (ie core Walmart shoppers) were less likely to own a computer, which at the time was the only way to shop online. Fast-forward to today and not only has there been significant price deflation in the PC category, but consumers can now purchase goods from their smartphones94 (which one-third of Walmart shoppers now own) as well as other new media such as lower-priced netbooks as well as tablets. Online shopping has been democratized.

It’s also important to remember that Walmart’s shopper base has broadened over the past several years, with many higher-income, tech-savvy consumers trading down during the recession in a bid to find better value at the shelf. Many of these shoppers see Walmart as a way to save a few bucks on weekly groceries, but when it comes to downloading music, not to name the elephant in the room, but surely there are more obvious choices.

Yet it wasn’t just a lack of consumer demand: Walmart was also late to the e-commerce arena because of structural reasons. According to a former Walmart.com executive, many store managers initially feared that making a push for e-commerce would cannibalize their in-store sales (and consequently their bonuses). This approach, not exactly customer-centric or sustainable, was not unique to Walmart. Across the Atlantic, Germany’s Media-Saturn suffered from the same fears and it was only in 2011 that Europe’s largest consumer electronics chain finally succumbed to demand with plans to launch a transactional website.

In any case, e-commerce is the fastest-growing retail channel today and Walmart has no choice but to embrace the new digital world, not only because it is a long-term consumer-driven trend but also because, as we have discussed, Walmart must find alternative avenues for growth in its domestic market:

If I had to guess, social commerce is the next area to really blow up.

(Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook)

In support of this new strategic focus and to serve the digital consumer more broadly, Walmart has made a number of key investments over the past few years, including the acquisition of online movie service Vudu which is enabling it to go head to head with the likes of Netflix and iTunes, the launch of a beta online grocery service in San Jose, the nationwide expansion of its Pick Up Today programme, and notably the $300 million acquisition of social media technology platform Kosmix. The purchase of Kosmix, which has been integrated into a division called @WalmartLabs, was very un-Walmart and took many analysts by surprise; however, it could only be viewed as a step in the right direction as it is helping Walmart to tackle two key areas where it had virtually zero experience – mobile and social commerce.

By 2015, shoppers around the globe are expected to spend $119 billion on goods and services purchased through their mobile phones. It’s important to point out here that much of this growth will come at the expense of traditional e-commerce, but still represents a fast-growing sector nonetheless. Meanwhile, the global social commerce market, virtually non-existent in 2010, is expected to reach $30 billion by 2015. Half of this will come from the United States.95

It may sound fluffy to some, but companies can genuinely drive sales socially. Take Gap, for example. The struggling apparel retailer rang up sales of $11 million in just one day by partnering with Groupon.96 Going forward, we will see many more retailers pursue flash sales and group buying. Not only does it create a sense of urgency and excitement among shoppers, but it also enables retailers to genuinely translate the promotional experience online and shift stock where needed.

Social media on the whole is rapidly changing the way consumers engage with brands and retailers and, if used correctly, can also provide companies with a wealth of information about their customers. The challenge, however, is transferring the sheer amount of data and feedback into actionable insight.

Within Walmart, Asda has been the pioneer in this field. By monitoring real-time customer input from social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and other online forums via its Online Reputation Booth (ORB), it has been able to respond quickly to customer queries and get feedback on specific products. For example, Asda once noticed a flurry of (unrelated) social media users discussing how their Bourbon biscuits suddenly tasted differently. Asda fed those comments back to its biscuits buyer who confirmed that the retailer had in fact recently changed suppliers. Thanks to the feedback from customers, Asda made the decision to change quickly back to its original biscuit supplier. ‘Social media is a free, massive focus group, taking place in real time. And it is taking place with or without your permission’, said Rick Bendel, Walmart’s global chief marketing officer, who is based in the UK.97

Consumers today want to share, they want to be heard, and retailers are missing a trick if they are not listening. ‘It was clear to us that word-of-mouth marketing had been elevated to a new level. Fed by the rise in technology and ease of access to the web, peer-to-peer endorsement was now turbo-charged’, Bendel noted.98 Asda was able to further capitalize on this general shift in consumer mind-set when it came time to re-launch its private label line, now known as Chosen By You. This was the largest-ever private label re-launch in UK history and proof that retailers can go a long way by simply listening to their customers. All 3,500 of the original products had been blind-tasted by at least 50 consumers and more than two-thirds of those had to approve the product.99

Prior to the re-launch, the range was generating annual sales in excess of £8 billion (or 85 per cent of Asda’s private label sales) and being purchased by 92 per cent of Asda shoppers, so all in all it wasn’t a bad idea to ask the people buying it before making any changes.100 The result? Not only did shoppers notice a quality improvement across the board but Asda uncovered valuable item-related preferences (ie toffee-flavoured ice cream and lemon cupcakes), which led to NPD and consequent sales increases. The message is simple – retailers must get customers involved, both online and in person.

It’s important to bear in mind, however, that the UK is a nation of 62 million consumers, whereas the United States is home to nearly five times as many people. Asda therefore will find it much easier to involve customers in the decision-making process, to monitor feedback, and even to use social media to track competitive activity. During heavy snow, Asda was able to respond to customers experiencing delays to their grocery home-shopping order, prompting the business to communicate more quickly with affected customers. This would be much harder to do in the United States where the volume of activity is much, much greater.

However, Walmart is recognizing the need to harness data and get closer to its shoppers in the process, and, again in a very un-Walmart fashion, created a Consumer Insights Division in 2011. If this were any other retailer, such an announcement would be deemed relatively insignificant. But this is Walmart – the retailer who has traditionally shunned such initiatives for being too fluffy and adding unnecessary cost into the business. So why the change of heart? After two years of comparable sales declines, Walmart has finally recognized that it needs to do a better job when it comes to leveraging shopper insights. Like Asda, Walmart US is listening to shoppers via social media: at the time of writing, Walmart had 6 million Facebook fans, half a million of whom were providing feedback on transactions.101 The challenge is ensuring that the right people within the Walmart organization receive that feedback and respond to it. ‘In the future, we will dramatically expand the opportunity to listen to and engage with our customer’, said Cindy Davis, who heads the Consumer Insights Division.102 As part of that process, Walmart lifted a decade-long ban on data sharing in 2011, and is now working closely with market research firms like Nielsen and SymphonyIRI in a bid to gain deeper insights into shopper purchases. As Sam Walton always said, ‘There is only one boss – the customer. And he can fire everybody in the company from the chairman down, simply by spending his money somewhere else.’

Amazon – ‘the Walmart of our era’

Looking back to the early success of Walmart Supercenters, and hypermarkets in general, the concept won based on three principles. Firstly, the convenience of buying everything under one roof. Secondly, the lowest prices around. And thirdly, the broadest assortment you could imagine. Does that sound familiar? Yes, that sounds a lot like e-commerce today.

‘In global e-commerce, we will not just be competing. We will play to win’, Mike Duke told investors at the company’s 2011 Shareholders Meeting. There is only one company in the world unlikely to be losing sleep over those comments – Amazon.

In fact, it’s far more likely that Amazon is keeping Bentonville awake at night. Despite a number of key differences between the two companies – Amazon’s best-selling item is the Kindle, Walmart’s is the banana103 – they are finding themselves closer competitors by the day. The future is digital and Amazon is extremely well placed to cater to it. Walmart’s e-commerce sales are estimated to be around $6 billion, which is peanuts next to Amazon’s $34 billion.104 By 2024, Amazon is expected to overtake Walmart as the largest retailer in the world.105

So how is it doing it? Ironically, it is beating Walmart at its own game – pricing and assortment. Pricing is far more transparent online, although bricks-and-mortar retailers are increasingly making use of price comparison apps and other forms of price guarantees in order to bridge the gap. A 2011 study by Wells Fargo found that Amazon was up to 19 per cent cheaper than Walmart on a basket of goods (or about 9 per cent cheaper when you factor in shipping costs).106 This opens up a debate on whether online retailers should be subject to paying sales tax but, regardless, it is a disadvantage to Walmart, whose internet prices are generally comparable to those found in-store.

In terms of assortment, pure-play online retailers are not constrained by shelf space. Amazon offers approximately 14 times the number of products that Walmart does. In electronics, for example, Amazon offered 2,016 types of digital camcorders versus the 96 found on Walmart.com.107 Two months after the initial Wells Fargo study, the firm compared prices once again and found that not only did Amazon have more products in stock than its competitors, but it increased its prices by an average of 10 per cent compared to the first study on products that were sold out at rivals.108

Morgan Stanley’s Scott Devitt wrote in 2011: ‘Amazon.com is the Walmart of our era but it’s better, in our view – Amazon.com is the combination of a technology and logistics company, allowing it to participate in a transition of physical to digital retail supported by a store-less (in Seattle) business model that leads to higher long-term economic returns.’109

The future looks bright for Amazon, and more challenging for Walmart.com. Unlike Walmart, Amazon has a massive opportunity to expand simply by growing sales with existing customers (ie stealing share from competitors such as Walmart itself). Amazon’s 121 million shoppers spend an annual average of $275 whereas Walmart’s 300 million shoppers spend $750 per year.110 If we factored in the money spent on groceries and at Sam’s Club, the gap would be even more astonishing.

In terms of international growth, pure-play online retailers such as Amazon are able to penetrate new markets more quickly than those with a bricks-and-mortar presence. It is far less risky and cost-intensive to launch a new website compared to investing in a chain of stores. Since inception, it took 46 years for Walmart’s International division to account for 25 per cent of total sales. For Amazon, it took eight.111

Looking ahead, we cannot rule out Walmart taking a leaf from Amazon’s book by entering a new market purely with a domain name. Fashion retailers and department stores are spearheading this trend, with Macy’s, Bloomingdales, Saks, Next, John Lewis and Marks & Spencer all prime examples. This is a fantastic way to test demand for a brand and to generate awareness, perhaps before a physical launch. A Saks website without store support is still offering something new to the market. However, a Walmart website without store support is surely just a smaller and potentially more expensive version of… well, Amazon.

Walmart therefore needs to leverage its thousands of physical stores to support its e-commerce strategy. This is how they can compete against pure-play online retailers. While online is without a doubt an increasingly important aspect of retailing today, let’s not forget that a very small percentage of shoppers today buy only online. They still want the physical in-store experience and, of course, Amazon cannot offer this (although there have been rumours of Amazon launching physical stores for years now). Walmart will not win in e-commerce – Walmart will win in multi-channel.

Mr Simon told the authors: ‘We want our customers to be able to shop at Walmart whenever, wherever and however they want by integrating the shopping experience between bricks-and-mortar stores and e-commerce. This also reflects the continued integration of customers using web-based devices to shop our stores and to research and shop online, as well.’ With initiatives such as Site-to-Store and Pick Up Today, the retailer is certainly heading in the right direction.

Globally, there are plenty of opportunities for Walmart to grow e-commerce sales. They have been ramping up investment in Asia and Latin America, having quietly launched transactional sites in Brazil, China, Mexico and Chile over the past several years.

China in particular is poised for an e-commerce boom – by 2016, it is expected to overtake the United States to become the world’s largest e-commerce market. Currently, one in four of the world’s internet users live in China; this is equivalent to 460 million which is greater than the entire US population.112 This hasn’t gone unnoticed in Bentonville.

Walmart has ramped up online activity in China by launching a transactional site for its Sam’s Club operation as well as acquiring a minority stake in Yihaodian, a fast-growing online supermarket. Yihaodian distinguishes itself from bricks-and-mortar retailers by offering a broad assortment of 100,000 SKUs compared with the 20,000 found in a typical Chinese supermarket. Prices are 3–5 per cent cheaper than those found in bricks-and-mortar retailers, making it an attractive fit for Walmart.113

Most Chinese e-commerce retailers specialize in a single product line; however, Yihaodian has found success selling across a multitude of categories. Its core lines make up the broader grocery category, although products in the baby care, consumer electronics and apparel categories are also featured. Nonetheless, given the country’s poor infrastructure, achieving economies of scale in the supply chain will be Walmart’s biggest challenge in China.

Brazil, which is home to 40 per cent of Latin America’s internet users, is another market to watch.114 Walmart’s Brazilian e-commerce operations offer 10 times the assortment available in-store and have been growing at double the market rate in recent years.115 The country’s burgeoning middle class will continue to support this growth: according to Forrester Research, the market is expected to grow at an 18 per cent annual rate with total sales expected to reach $22 billion by 2016, nearly three times more than in 2010.116

Looking ahead, Walmart will expand its reach in more markets and categories, and it will grow mobile commerce in emerging markets, given that in many of these countries there are far more mobile phones than internet connections. According to the Boston Consulting Group, in 2010 there were 610 million regular internet users in the BRICI markets (Brazil, Russia, India, China and Indonesia) compared to a whopping 1.8 billion mobile phone connections.117

But online growth will not be restricted to emerging economies; it is also a priority in more mature, sluggish markets such as Japan where the retailer plans to grow e-commerce sales twentyfold over a five-year period to 2016. Customer count is expected to grow tenfold during that time. Walmart has had an online presence in Japan for over a decade, yet only 47 stores are used as picking centres for home delivery. By the end of 2013, this will grow to 350 stores.118 Despite a stagnant economy, shrinking population and ongoing contraction of the broader retail sector, Japan’s e-commerce sector continues to grow at approximately 10 per cent annually.119

One would have expected the densely populated, tech-savvy nation to be a goldmine for e-commerce. Yet, compared to the rest of the world, Japan has been surprisingly late to embrace this channel – particularly for fruit and vegetables as many consumers still prefer to see, touch and feel before buying. However, the recession has changed the way consumers behave, research and ultimately purchase goods. More people staying at home have created opportunities for the sector, and retailers such as Walmart are now looking to capitalize on this trend. However, Walmart will face some strong domestic competition as it looks to expand its online operation: two-thirds of the 90 million internet users in Japan shop via Rakuten, the country’s largest online shopping mall.120

Growth in e-commerce, both at home and abroad, will undoubtedly impact the way Walmart – and all retailers for that matter – operate their physical stores. In the next decade, as more consumers around the world gain access to online shopping, there will be a need for retailers to create a more compelling in-store experience. Shopping is still a pastime in most countries, developed and emerging, and physical stores can capitalize on this as a means of differentiating from the encroaching online channel. Price and assortment can be replicated too easily; instead, retailers will need to ramp up their efforts in areas such as ancillary offerings (ie in-store daycare, spas, social areas) and retail theatre, and, crucially, invest in customer service.

Notes

1 Walmart 1982 Annual Report, p 4. http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/irol/11/112761/ARs/1982AR.pdf

2 2011 net sales $419 bn. http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/104169/000119312511083157/

dex13.htm

3 Walmart 1981 Annual Report, p 4. http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/irol/11/112761/ARs/1981AR.pdf

4 Walton (1992), p 64

5 Progressive Grocer, Driving Wal-Mart’s growth engine: a dramatic shift in strategic assumptions has propelled the retailer’s spectacular expansion since the death of founder Sam Walton, 1 February 2004

6 http://www.rogersarkansas.com/museum/rogershistory.asp

7 All based on US population divided by 2010 store numbers from 10ks

8 Walton (1992), p 54

9 Walton (1992), p 256

10 As per 2011 10k (2010 numbers) p 9. http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/104169/000119312511083157/

d10k.htm

11 Walton (1992), p 254

12 The Wall Street Journal, Price war in aisle 3 – Wal-Mart tops grocery list with Supercenter format; but fewer choices, amenities, Patricia Callahan and Ann Zimmerman, 27 May 2003

13 Supermarket News. http://www.pbs.org/wsw/tvprogram/drbulreportwmt.pdf

14 http://www.aptea.com/company.asp

15 The Wall Street Journal, A&P heading to the checkout counter? Dave Kansas, 10 December 2010. http://blogs.wsj.com/marketbeat/2010/12/10/ap-heading-to-the-checkout-counter/

16 http://www.thekrogerco.com/corpnews/corpnewsinfo_timeline.htm

17 Planet Retail

18 Supermarket News, Aldi fires up value fight in Dallas market, Jon Springer, 5 April 2010. http://subscribers.supermarketnews.com/retail_financial/aldi-fires-up-value-0405/

19 Philly.com, Carrefour seeks N.J. outlet. French retailer picks Voorhees site, Susan Warner, Inquirer Staff Writer, 24 October 1990. http://articles.philly.com/1990-10-24/business/25891701_1_carrefour-french-retailer-shopping-center

20 Discount Store News, Hypermart USA units get SuperCenter-type facelift – Wal-Mart Supercenter combination stores; Hypermart USA hypermarkets, Arthur Markowitz, 9 April 1990

21 Arkansas Business, Arkansas consumers soon will test Wal-Mart’s new supermarket concept, David Smith, 28 September 1998

22 Walmart 1979 Annual Report, p 1. http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/irol/11/112761/ARs/1979AR.pdf

23 PR Newswire, Michaels Stores consummates acquisition of Helen’s Arts and Crafts Stores from Wal-Mart, 2 May 1988. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-6635339.html

24 Fortune, Nelson D. Schwartz, 16 February 1998. http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1998/02/16/

237707/index.htm

25 Walmart 2011 Annual Report and Kroger 10k. Kroger total sq ft is 149m

26 The 600 conversions statistic was based on author research from Walmart 10ks.$425 statistic source: Walmart 1997 Annual Report, p 3. http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/irol/11/112761/ARs/1997_annualreport.pdf

27 Walmart 1997 Annual Report, p 3. http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/irol/11/112761/ARs/1997_annualreport.pdf

28 Author research/Walmart 10k

29 Food Marketing Institute. http://www.fmi.org/facts_figs/keyfacts/?fuseaction=storesize

30 Author research based on Walmart 10ks

31 2010 10k

32 Walmart, as of August 2011

33 Census. http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/usinterimproj/

natprojtab02a.pdf

34 http://www.knowledgeatwharton.com.cn/index.cfm?fa=printArticle&articleID=1420&languageid=1

35 Walmart 1978 annual report. http://media.corporate-ir.net/media_files/irol/11/112761/ARs/1978AR.pdf

36 Walmart/Walmart contact/Planet Retail

37 Walmart contact

38 http://investors.walmartstores.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=112761&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=1482363&highlight=

39 The Wall Street Journal, With sales flabby, Wal-Mart turns to its core, Miguel Bustillo, 21 March 2011. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB100014240527487033284045762071616

92001774.html

40 http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=-VJSAAAAIBAJ&sjid=mzYNAAAAIBAJ&pg=3688,3873785&dq=walmart+sells+convenience+stores+to+conoco&hl=en

41 The Wall Street Journal, Wal-Mart to build a test supermarket in bid to boost grocery-industry share, Emily Nelson, Staff Reporter, 10 June 1998

42 The Wall Street Journal, as above

43 Author research based on Walmart 10ks

44 Food Marketing Institute. http://www.fmi.org/facts_figs/?fuseaction=superfact

45 Independent, Asda plans move into convenience stores, Susie Mesure, Retail Correspondent. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/asda-plans-move-into-convenience-stores-437360.html

46 Independent, US business will make money in three years, Tesco predicts, James Thompson, 6 October 2010. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/asda-plans-move-into-convenience-stores-437360.html

47 Fortune, The rise of the grocery co-op, Beth Kowitt, writer-reporter, 19 September 2010. http://money.cnn.com/2010/09/16/news/companies/grocery_coop_

Brooklyn.fortune/index.htm

48 Planet Retail

49 USA Today, Most foreclosures pack into a few counties, Brad Heath, 6 March. http://www.usatoday.com/money/economy/housing/2009-03-05-foreclosure_N.htm

50 Supermarket News, Next Tesco CEO: Fresh & Easy future uncertain, 20 September 2010. http://supermarketnews.com/news/fresh_easy_0920/

51 164 as per FY 2011 annual report. http://ar2011.tescoplc.com/overview/tesco-around-the-world.html#null