[N]o one loves his predecessors more deeply, more fervently, more respectfully, than the artist who gives us something truly new; for respect is awareness of one’s station and love is a sense of community. Does anyone have to be reminded that Mendelssohn – even he was once new – unearthed Bach, that Schumann discovered Schubert, and that Wagner, with work, word, and deed, awakened the first real understanding of Beethoven? 1 ARNOLD SCHOENBERG

He [Mendelssohn] is the Mozart of the nineteenth century, the most brilliant musician, the one who most clearly sees through the contradictions of the age and for the first time reconciles them. 2 ROBERT SCHUMANN

Schoenberg’s appreciation, characteristically as generous as it is backhanded, brings the difficulties inherent in the notion of “Mendelssohn as progressive” into clear focus. On the one hand, it can be difficult to remember that his music was ever in any significant way “new.” “Progressive” more readily conjures up Wagnerian forays into the uncharted realms of the music of the future than the cultivation of the familiar, if daunting, confines of the past. Mendelssohn, however – alone among composers between Beethoven and Brahms – achieved his most characteristic and personal expression in sonata-form works, while, as Charles Rosen has observed, some of his more intimate lyric utterances may “charm, but they neither provoke nor astonish.” 3

Mendelssohn’s music only rarely aspires to provoke, but if his larger forms fail to astonish, it is too often likely that we simply are not paying attention; and this brings us to the second problem. As Schumann’s characterization suggests, Mendelssohn contrived to resolve the conflicts of his age by assimilating almost everything that was “truly new” in his style into a tonal, thematic, and formal language of seamless cohesion and Mozartean refinement. As a result, it is often difficult to catch him in the act of doing much of anything at all, much less something out of the ordinary. His most striking achievements tend to elude detection, duping us into a satisfied assumption of condescending comprehension. Even Tovey often mistook Mendelssohn’s formal strategies for schoolboy pranks and “easy shortcuts to effect.” 4

The problems to which Mendelssohn’s strategies represent solutions were engendered by two fundamental “contradictions” inherent in the early nineteenth century’s confrontation with sonata forms. First, the richly expressive harmonic and gestural vocabulary of Romantic music tends to undercut the significance of the large-scale tonal processes that animate the sonata forms of the Classical era. In turn, as the opposition of tonic and secondary key as well as the function of the thematic design as an articulation of that opposition dissolve into the moment-by-moment flux of the expressive surface, the rationale for tonal resolution through formal recapitulation loses much of its dramatic urgency. There was, as Viktor Urbantschitsch put it, a “recapitulation problem”; a suspicion that the recapitulation was simply an “obligatory symmetrical analogy to the first part [the exposition]” that offered composer and listener alike nothing more than “the inflexible repetition of that which has already been said.” 5

This unsavory prospect was rendered even less palatable by the second “contradiction” – the Romantic tendency to place the climax near the end of a piece. Not only would that climax be forestalled by wearisome recapitulatory pedantries for which a rousing, if often formally inexplicable, coda might or might not offer adequate compensation, but the structurally crucial – and always dramatically calculated – effects achieved by Haydn, Mozart, or Beethoven at the opening of the recapitulation, marking the initiation of the movement’s formal process of resolution, resist easy assimilation into an end-oriented dramatic trajectory. Berlioz’s progressive transformations of the idée fixe in the first movement of his Symphonie fantastique represent a particularly radical response to these problems; a response, however, that threatens to put every other constituent element of the form into question. Mendelssohn’s strategies, characteristically, lean more toward formal insight than hallucinatory mania.

These “problems” mark the fault lines of a fundamental shift in formal meaning from tonal process to thematic expression – in Dahlhaus’ characterization, the replacement of “the idea of a balance of parts distinguished by their functions . . . by the principle of developing ideas, the concept of musical form as something which presented the history of a theme.” 6 The most convincing formal procedures in Mendelssohn’s early works typically emerge in his negotiation of these fault lines – specifically in the reconciliation of his highly individual lyric impulse with the imperatives of sonata-form processes. If that reconciliation at times tamps down the dramatic impact and provocative intensity of his music, it offers in compensation a reevaluation of musical relations that often proves as logically inevitable as it is intensely beautiful and “truly new.”

One example from Mendelssohn’s preposterously masterful early output, the Piano Quartet in F minor op. 2, completed in 1823 when the composer was fourteen, offers a sense of the depth and delicacy with which that reconciliation could be accomplished. The first movement is one of the beautifully crafted, but stiffly compartmentalized and verbosely articulated sonata forms that seem to have been the pedagogical ideal of Carl Friedrich Zelter’s schooling and the epitome of classicist formal thought. The second movement, an Adagio in D![]() major, draws us into a more distinctly Mendelssohnian realm.

major, draws us into a more distinctly Mendelssohnian realm.

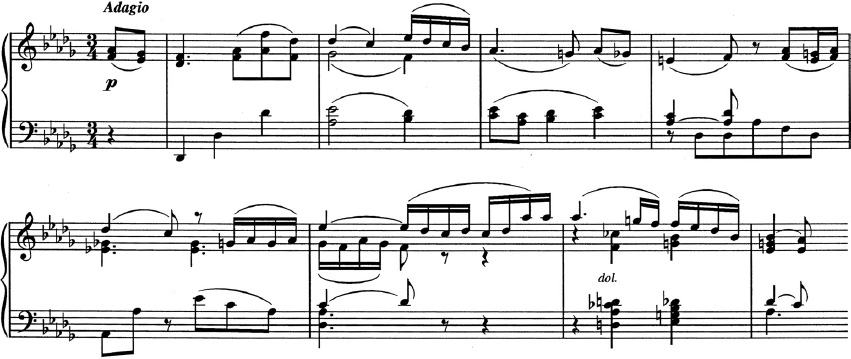

The Adagio is not, strictly speaking, monothematic, but the first and second themes are obviously very closely related; both derive, in turn, from the opening theme of the first movement (Example 5.1 ).

Example 5.1 Piano Quartet in F minor op. 2, movement 2

(a) first theme, mm. 1–9

(b) second theme, mm. 25–33

The first-theme version exhibits a restrained but affecting lyricism. The radically simplified outline of the second-theme version weaves through canonic overlappings in the strings, floating high over the piano’s barely audible tremolos, achieving a kind of ecstatic placidity. The development verges on lyric recklessness, simply repeating these intertwinings over and over as they drift through a shimmering modulatory field.

Eventually, the harmony begins to slide back toward the tonic. But at the double return, the tonic teeters on its second inversion, pointing toward, rather than accomplishing, resolution (Example 5.2 ). The main theme returns as though it were the second theme, floating high in the violin, continuing to occupy the registral space maintained throughout the development and even tracing a path through the same pitches as its simplified second-theme outline in the exposition. The piano, which had originally introduced the main theme in the opening bars of the movement, simply continues the rippling sextuplets it has played throughout the development section.

Example 5.2 Piano Quartet in F minor op. 2, movement 2, opening of recapitulation, mm. 68–76

Everything returns, but nothing is quite as it was; obligatory symmetry dissolves into ethereal transformations, and repetition gives way to that which had been only hinted at before. The earlier stages of the story fall away. The main theme never returns in its original form, and the second theme never returns at all, replaced by a murmuring coda of veiled allusions to transitional passages in the exposition. The thematic and tonal dialectic set out in the exposition resolves in a synthesis that simultaneously realizes and recasts the processive shape of sonata form, subsuming tone color, register, and texture not as ornamental accompaniments to the musical idea, but as the vehicles through which that idea, the lyrically unidirectional story of the theme, is told. In this most delicate of climaxes recapitulation becomes transformation and culmination.

Slow movements are, of course, the natural habitat of lyricism in sonata-form works; but Mendelssohn’s genius lay less in the intensity of expression that flowers here – it remains distinctly Mendelssohnian in its restraint – than in a mutual accommodation of formal process and expressive design that carries the movement’s lyric impulse far beyond its modest origins.

The disjointed verbosity that weighs down the first movement of op. 2, on the other hand, is typical of the classicist dilemma the young Mendelssohn, like most of his contemporaries, faced. Even confined to the expressive realm of the “contrasting second-theme group,” outbreaks of lyricism posed severe problems of pacing and function, dissipating forward momentum in the breadth of their leisurely unfolding, and subverting harmonic tension in a wash of expressive detail. 7

Mendelssohn developed various responses to these problems in the great works of his early maturity, ranging from the coiled spring that briefly masquerades as the lyric second theme in the first movement of the Octet op. 20 (1825, revised and published 1830), to the magnificent seascape second theme of the Hebrides Overture op. 26 (1829–35). 8 But his most intriguing synthesis of lyricism and formal process shapes the first movement of the least appreciated of these early masterpieces, the String Quintet in A major op. 18 (first version, 1826, revised and published 1832) – a touchingly individual assimilation of the influences of his predecessors through which the composer fashioned one of his most personal and progressive utterances. It is a music grounded in the past that is truly new, pointing unobtrusively to the future.

As always, the composer’s design is enveloped in a luminous sheen that tends to mask the originality and implications of his strategies. The premises of that design rest on a distinctly Mozartean balance of parts clearly – at first glance, perhaps, all too clearly – “distinguished by their functions.” Exposition, development, recapitulation, and coda follow one another in orderly succession, seeming to fulfill their functions like cogs in a sleek neo-classical machine. But in contrast to the slackly elastic outlines of the first movements of Mendelssohn’s earlier pedagogically classicist chamber works, with their inevitable diffusion of dutiful first-theme bustle into indulgent lyric inflation, the exposition in the first movement of op. 18 spins out an infectiously energetic trajectory from its lyric, gently formal main theme. 9

The exposition recalls the structural design of Mozart’s G major and A major quartets K. 387 and 464; works in which Mozart, in one of his periodic confrontations with Haydn, was working out his own reformulation of the relation of formal process and motivic impulse. In both Mozart’s and Mendelssohn’s designs, lyricism is not simply accommodated as the contrasting, and usually disruptive, structural “other”; it is posited as the primary topic – the “main theme” – of the music, engendering rather than derailing the structural process. All of the primary thematic material – indeed it seems almost every note – of the first movement of op. 18 can be traced back to the lyrically unfolded first-inversion tonic triad that initiates the main theme.

This motivic impulse manifests itself in a web of thematic relations as clearly articulated as the structural succession of the work’s formal design. Less obviously, it is deployed over – and, indeed, manifests – a trajectory of increasing pace, expanding sonorous palette, linear fragmentation, and harmonic destabilization that almost surreptitiously fractures both the lyric continuity and the orderly sequence of the formal design through which it is realized.

The main theme, for all its Classical balance, exhibits a curious reticence, self-absorbed in its hesitant pauses, oddly mulling fragmentation and repetitions, and increasingly meandering melodic and harmonic course. These traits are intensified in the compressed juxtapositions of the transition and spill over into the second theme, which, thrown slightly off balance metrically, harmonically, and even texturally from the first, never quite succeeds in establishing the secondary key, E major, with any authority. Even as the second theme does finally begin to gather itself into a cadence (mm. 102ff.),

it gets caught up in itself; dangling from the first violin’s repeated a″–g![]() ″ neighbor-note figure, it takes only a gentle nudge from the cello to suddenly lift the passage from E major to F

″ neighbor-note figure, it takes only a gentle nudge from the cello to suddenly lift the passage from E major to F![]() minor (Example 5.3

).

minor (Example 5.3

).

Example 5.3 String Quintet in A major op. 18, movement 1, cadence theme, mm. 102–17

At first this might seem to be some sort of Mozartean “purple passage,” delaying and intensifying the inevitable cadential affirmation of the dominant. But the exposition never returns to E major; it closes, quietly but unambiguously, in F![]() minor. This is not really a purple passage, then, or a “three-key exposition” in any normal sense of the term, or a modulatory design moving from I to vi along the lines of the first movement of Beethoven’s String Quintet op. 29; the exposition simply closes in the wrong key. But the delicate flash of harmonic color this entails is only part of the story.

minor. This is not really a purple passage, then, or a “three-key exposition” in any normal sense of the term, or a modulatory design moving from I to vi along the lines of the first movement of Beethoven’s String Quintet op. 29; the exposition simply closes in the wrong key. But the delicate flash of harmonic color this entails is only part of the story.

The end of the second group became entangled in one of the seemingly inescapable half-step neighbor-note figures that are woven through the exposition (the first 4-3 pairing throbs momentarily in mm. 5–6 of the main theme). At the end of the exposition, however, the figure’s inflectional tendencies are reversed: g![]() ″ suddenly resolves up to a″ instead of a″ resolving down to g

″ suddenly resolves up to a″ instead of a″ resolving down to g![]() ″ (and, secondarily, c

″ (and, secondarily, c![]() ″ is no longer drawn down toward b′). These are of course simple inflectional facts of tonal life that would barely

draw attention on their own. But this reorientation lifts the melodic framework of the cadential theme up from the E major triad (laid out melodically in second inversion, b′–e″–g

″ is no longer drawn down toward b′). These are of course simple inflectional facts of tonal life that would barely

draw attention on their own. But this reorientation lifts the melodic framework of the cadential theme up from the E major triad (laid out melodically in second inversion, b′–e″–g![]() ″) to an F

″) to an F![]() minor triad (c

minor triad (c![]() ″–f

″–f![]() ″–a″), reestablishing the inflectionally stable elements of the melodic line in almost exactly the disposition that frames the opening of the main theme (e″–c

″–a″), reestablishing the inflectionally stable elements of the melodic line in almost exactly the disposition that frames the opening of the main theme (e″–c![]() ″–a″).

″–a″).

At the same time, while locally this reorientation of the thematic topology introduces a fairly severe harmonic disruption, on a larger scale, it turns the end of the exposition into a transition back toward the tonic. In this sense, the intrusion of F![]() minor might register as a truly deceptive cadence carried out on a structural level. The instability of the second group as a whole might then be heard as a manifestation of an episode-like function, passing through, rather than confirming, the dominant key; the peculiar weakening of the local tonic pitch, E, throughout this passage certainly suggests that this is the case. The resulting double meaning of the passage, simultaneously intensifying and reducing tension, is characteristic of Mendelssohn’s almost wistfully ephemeral reformulation of the past in his finest works.

minor might register as a truly deceptive cadence carried out on a structural level. The instability of the second group as a whole might then be heard as a manifestation of an episode-like function, passing through, rather than confirming, the dominant key; the peculiar weakening of the local tonic pitch, E, throughout this passage certainly suggests that this is the case. The resulting double meaning of the passage, simultaneously intensifying and reducing tension, is characteristic of Mendelssohn’s almost wistfully ephemeral reformulation of the past in his finest works.

The head of the main theme returns at the end of the development section, poised over a first-inversion tonic chord (m. 250). We are almost home, but the decisive cadence is once again nudged out of place by the cadential theme, this time pulling the music into the thoroughly implausible key of G minor (m. 254). This startling intrusion negates the leading tone itself, introducing in its place a new cluster of chromatic upper neighbors – b![]() ″ and d″ – gravitating toward the triadic corner posts of main theme – a″ and c

″ and d″ – gravitating toward the triadic corner posts of main theme – a″ and c![]() ″. At this point, it becomes clear that tonally functional harmonic hierarchies are being subordinated to a purely inflectional play around the pitches of the tonic triad, deployed in the thematic gestalt of the main theme. That gestalt might best be thought of as the movement’s pôle harmonique

, the stable sonorous configuration around which its harmony, form, and thematic articulations revolve, deviate, and converge.

10

As the end of the development section gradually works its way back to the tonic, the motivic frame is drawn back to its “polar” home configuration (m. 278).

″. At this point, it becomes clear that tonally functional harmonic hierarchies are being subordinated to a purely inflectional play around the pitches of the tonic triad, deployed in the thematic gestalt of the main theme. That gestalt might best be thought of as the movement’s pôle harmonique

, the stable sonorous configuration around which its harmony, form, and thematic articulations revolve, deviate, and converge.

10

As the end of the development section gradually works its way back to the tonic, the motivic frame is drawn back to its “polar” home configuration (m. 278).

The cadence theme functions, then, primarily to derail V–I cadential resolutions at crucial junctures of the movement’s lucidly Mozartean formal design. Tonal process is superseded, if not quite countermanded, by the pervasive snares of the motivic web spun from the unassuming triadic wisps of the lyric main theme. Although the movement stakes out conventional harmonic realms and formal articulations, these are exploited less as the agents of large-scale tonal processes – the traditional polarity of structural dissonance and resolution – than as the boundaries of shifting fields of harmonic gravity that reorient the inflectional relations established by the tonic configuration, the pôle harmonique , of that motivic web. 11 Tonality, that is to say, has become a function of thematic configuration, and form is becoming the story of that thematic configuration and its vicissitudes over time.

Indeed, neither the establishment of large-scale harmonic tension nor its resolution is accomplished in any normal sense within the confines of exposition and recapitulation; it is the function of the coda to synthesize the resolution and closure of the music’s motivic and harmonic impulses. 12 The displacement of the movement’s structural climax to the coda is, of course, a hallmark of the Romantic style; but here, for once, it seems to emerge naturally from the mutual interplay of form and content that has shaped the movement from the beginning.

After a last intrusion of the cadence theme at the end of the recapitulation (m. 237), this time only slipping to the tonic minor (leaving a″ and e″ in place, with c![]() ″ pressing back toward c

″ pressing back toward c![]() ″), the main theme returns, espressivo

, to open the coda (Example 5.4

). Its expressivity is focused in a touching simplification of the accompanying texture and harmony that draws the theme into a flowing I–II7

–V7

–(I) four-bar cadence that encapsulates dominant and tonic, tension and resolution, expression and articulation, in purely lyric terms and proportions. The movement, which has flowed over every formal articulation in the course of its sprawling progress, simply rounds back into its transformed self, closing its lyric circle.

13

″), the main theme returns, espressivo

, to open the coda (Example 5.4

). Its expressivity is focused in a touching simplification of the accompanying texture and harmony that draws the theme into a flowing I–II7

–V7

–(I) four-bar cadence that encapsulates dominant and tonic, tension and resolution, expression and articulation, in purely lyric terms and proportions. The movement, which has flowed over every formal articulation in the course of its sprawling progress, simply rounds back into its transformed self, closing its lyric circle.

13

Example 5.4 String Quintet in A major op. 18, movement 1, mm. 261–69

The rest of the coda is concerned primarily with tying up an important registral thread, gradually climbing to an ecstatic c![]() ″′ (m. 305) that reaches back to the intrusion of the cadential theme at the end of the recapitulation (m. 237), where c

″′ (m. 305) that reaches back to the intrusion of the cadential theme at the end of the recapitulation (m. 237), where c![]() ″′ had been displaced to c

″′ had been displaced to c![]() ″′. Oddly enough, this fails to lead to a conclusive cadence or upper-voice descent to the tonic pitch, A. Even the first violin’s ascent to a″′ in the last two bars of the movement registers less as resolution than as a lingering recollection of the main theme; its point is not finality but incompleteness – a reluctance to let go.

″′. Oddly enough, this fails to lead to a conclusive cadence or upper-voice descent to the tonic pitch, A. Even the first violin’s ascent to a″′ in the last two bars of the movement registers less as resolution than as a lingering recollection of the main theme; its point is not finality but incompleteness – a reluctance to let go.

A wonderfully “poetic” gesture, this close offers striking evidence of Mendelssohn’s detailed control of the large-scale structural imperatives of a multi-movement sonata-form work. The first movement never steps beyond its melodically conceived design; formal process seems little more than a nostalgic recollection, and closure is really none of its business. The tonally defined structural process of the Quintet is only completed when the upper voice settles onto the tonic pitch in the last bar of the finale, a movement in which large-scale tonal relations fulfill their structural functions in a more straightforward way, and the thematic design functions to articulate rather than interfere with those relations.

In hailing Mendelssohn as the Mozart of the nineteenth century, Schumann also observed, in his own left-handed way, that “after Mozart came Beethoven; this new Mozart will also be followed by a Beethoven – perhaps he is already born.” 14 By 1840, when he wrote this, Brahms – the Beethoven who would follow Mendelssohn’s Mozart – was seven years old, and the future toward which the first movement of op. 18 discreetly points dawns in his early chamber works. Mendelssohn’s influence is almost palpable in the two String Sextets opp. 18 and 36, from the 1860s; the two Serenades opp. 11 and 16, and the Symphony no. 2 (1877), especially the first and third movements, belong to this family of works as well. All stand somewhat to the side of Brahms’ development, infused with an uncharacteristic directness of expression and gesture framed in the formal certainties of the past. They share strikingly similar thematic profiles – simple triadic outlines like the main theme of Mendelssohn’s op. 18 – marked by an inward-turning self-absorption manifested most clearly in lingering repetitions within phrases – an unhurried mode of thematic generation that might be termed Zurückspinnung . Most striking, perhaps, is Brahms’ adoption of Mendelssohn’s almost obsessive concentration on oscillating half-step figures that spawn new themes and from which unprepared, and – in purely local harmonic terms – distinctly far-fetched, modulations hinging on the reversal of neighbor-note inflectional relations are hung (op. 18, first movement, mm. 60ff.; op. 36, first movement, mm. 32ff.). On the other hand, it is striking that although Brahms’ harmonic language is far richer than Mendelssohn’s, he is considerably more circumspect about the structural role of these modulations, deploying them as colorful, but somewhat isolated, way stations along the course of Schubertian “three-key” expositions rather than following Mendelssohn’s more structurally subversive lead. 15 By the 1860s form has become more expansive, but at the same time less flexible.

This blend of melodicism, formal breadth, and barely disguised schematic inflexibility might seem a recipe for neo-classicism, but it was in Brahms’ op. 18 that Tovey found “in a mature form the expression of a deliberate reaction towards classical sonata style and procedure.” 16 As always, he is elusive about how that reaction manifests itself, but Kofi Agawu suggests a productive critical orientation in his overview of the symphonies. 17 In approaching these later works, Agawu urges the adoption of a dual perspective that takes into account two “fundamentally opposed compositional impulses”: the imperatives of a “pre-compositional” architectural design – sonata form, for example; and those of a “logical form” that “dispenses with the outer design of architects [sic] and assumes a form prescribed by the nature, will and destination of the musical ideas themselves.” 18 If in the first movement of Mendelssohn’s op. 18 the claims of form and content – architecture and idea – are balanced with seemingly effortless elegance, in the Brahms Sextets there is an undercurrent of uncertainty, a sense of lyricism already shading into withdrawal and loss. The neo-classicism Walter Frisch ascribes to these works is, perhaps, itself a vehicle of expression, a token of the composer’s regret over what Charles Rosen characterized as “the sense of an irrecoverable past” that will haunt his entire output. 19 Even the way thematic content maintains only a precarious equilibrium between technical sophistication and at least the pretence of an expressive directness that the composer only rarely indulged so unrestrainedly in later works seems to express that sense of loss. By 1860, the poise of the high Classical style had already slipped beyond Brahms’ reach, even through the mediation of Schubert and the young Mendelssohn.

In a number of works that follow op. 18, Mendelssohn continued to explore his own reactions to the Classical heritage in a series of confrontations with Beethoven. The String Quartet in A minor op. 13 (1827), is a valiant – if unsettlingly obsessive – foray into the world of the late quartets, in particular, the Quartet in A minor op. 132, which the young composer must have studied in manuscript.

20

In the slightly later Quartet in E![]() major op. 12 (1829), perhaps the most satisfying, if not the most outwardly provocative, of these works, Mendelssohn retreats to the more congenial lyricism of the “Harp” Quartet op. 74.

21

major op. 12 (1829), perhaps the most satisfying, if not the most outwardly provocative, of these works, Mendelssohn retreats to the more congenial lyricism of the “Harp” Quartet op. 74.

21

Once again, the structure of the first movement might seem almost too clearly delineated: the main theme reappears to mark each of the principal junctures in the “external form” of the first movement – the opening of the exposition, development, and recapitulation, and finally at the climax of the coda – but each time except the last in guises that momentarily weaken rather than reinforce the listener’s sense of formal articulation. The alterations are subtle – nothing like the Romantic frenzy expressed in the increasingly hysterical transformations of the idée fixe in the first movement of the Symphonie fantastique – but their purpose is the same: to assimilate the dynamic trajectory of “external form” to the “logical” unfolding of the story of the theme.

The story in op. 12 hinges on the theme’s gently elusive relation to the tonic key. The first violin traces its way through the framework of the tonic triad, but beneath it, details of voice-leading blur the boundary between E![]() major and its submediant, C minor. The effect is fleeting, but it is not simply coloristic; the tonic is less the structural given of the movement than the goal toward which that structure is moving – or at least drifting. The effect is heightened at the opening of the recapitulation, where Mendelssohn contrives to make the return of the main theme over an E

major and its submediant, C minor. The effect is fleeting, but it is not simply coloristic; the tonic is less the structural given of the movement than the goal toward which that structure is moving – or at least drifting. The effect is heightened at the opening of the recapitulation, where Mendelssohn contrives to make the return of the main theme over an E![]() major triad firmly planted on a tonic pedal in the cello sound unstable – a dissonance rather than a resolution.

major triad firmly planted on a tonic pedal in the cello sound unstable – a dissonance rather than a resolution.

As in the first movement of op. 18, it is left for the coda to draw the theme through a subtle harmonic reorientation into a cadential formulation that assimilates tonal process to the confines of a thematic impulse that straddles the boundary between the articulative, “architectural,” functionality of form and a lyricism that, as Mercer-Taylor has aptly put it, “would have seemed daringly pervasive even to Schubert”. 22 The movement closes in a dying fall of genuine poetic inspiration that Brahms seems to have recalled at the end of the first movement of his Third Symphony; he even follows Mendelssohn’s lead in bringing back the first-movement coda at the end of the finale.

In both works, the return of music from one movement in another obviously implies an overarching expressive design – a logical form – that could not be contained within the formal processes of the individual movements. Mendelssohn’s influence lies lightly on Brahms’ shoulders; not surprisingly, the challenge of maintaining the formal and expressive intensity his Beethovenian aspirations engender in the latter stages of op. 13 weighed far more heavily on Mendelssohn’s. As Mercer-Taylor observes, the “jagged juxtapositions and sudden changes of direction” that buffet the Finale seem to lack any “palpable sense of emotional motivation.” 23

The perplexing trajectory of the finale wavers uneasily between mannerism and convention, but its compositional logic is nearly impeccable. Its overheated outbursts mark the fissures where previously unsuspected cyclic processes break into the self-contained architectural form of the movement with a vehemence rarely encountered in Mendelssohn’s expressive world.

The third movement, a brief but eloquent Andante espressivo in B![]() major, closes in a tonic cadence strongly colored by its subdominant, which is, of course, E

major, closes in a tonic cadence strongly colored by its subdominant, which is, of course, E![]() major, the tonic of the work as a whole. The pull toward E

major, the tonic of the work as a whole. The pull toward E![]() major is so strong, in fact, that the final bar of the Andante, marked attacca

, registers unmistakably as V of E

major is so strong, in fact, that the final bar of the Andante, marked attacca

, registers unmistakably as V of E![]() major and retrospectively seems to transform the entire slow movement into a lyrically impassioned anticipation of the return to the tonic at the opening of the finale.

major and retrospectively seems to transform the entire slow movement into a lyrically impassioned anticipation of the return to the tonic at the opening of the finale.

But the first bar of the finale erupts in an agitated fanfare on V of vi (C minor in place of E![]() major once again!) that eventually leads us into a

full-blown sonata-form exposition in C minor, moving to G minor as its secondary key area (the use of the minor dominant is yet another foreshadowing of formal procedures usually associated with Brahms). This is not a movement that begins in the wrong key, but one that simply is

in the wrong key. The jagged juxtapositions that fracture the finale mark lines of stress where harmonic/thematic detail and tonal/formal structure – logical and architectural form – collide. This is perhaps most striking in a cluster of otherwise almost inexplicable changes of direction in the exposition – the intrusions of a secondary exposition articulated by its own network of themes, gravitating around the work’s “real” tonic: E

major once again!) that eventually leads us into a

full-blown sonata-form exposition in C minor, moving to G minor as its secondary key area (the use of the minor dominant is yet another foreshadowing of formal procedures usually associated with Brahms). This is not a movement that begins in the wrong key, but one that simply is

in the wrong key. The jagged juxtapositions that fracture the finale mark lines of stress where harmonic/thematic detail and tonal/formal structure – logical and architectural form – collide. This is perhaps most striking in a cluster of otherwise almost inexplicable changes of direction in the exposition – the intrusions of a secondary exposition articulated by its own network of themes, gravitating around the work’s “real” tonic: E![]() major within the C minor of the first group and its dominant, B

major within the C minor of the first group and its dominant, B![]() major, in the second group. A fleeting ambiguity that had colored the lyric opening of the first movement’s main theme has become the structural framework of the quartet’s roiling conclusion.

major, in the second group. A fleeting ambiguity that had colored the lyric opening of the first movement’s main theme has become the structural framework of the quartet’s roiling conclusion.

The return of the coda from the first movement seems to emerge naturally from the web of thematic resemblances and quotations that span op. 12, drawing the entire work back into the unassuming dimensions of its lyric beginning. But the sense of inevitability with which the coda returns – closing the work’s somewhat misshapen circle with the reestablishment of the commensurability of tension and resolution, elaboration and closure – arises from the integration of the cyclic design across every stratum of the work’s musical substance; motive and theme, harmonic detail and tonal structure, register, dynamics, and voice leading are all subsumed in its dying fall. 24

Cyclic procedures represent the most sweeping manifestation of logical form, breaking down the structural integrity – the closed architectural forms – of the individual movements of a work in order to fully realize what Agawu calls the “nature, will and destination of the musical ideas themselves.”

25

The four movements of op. 12 have grown together in ways that overwhelm the finale, its meaning rendered inexplicable except in the narrative context of the whole. That growth, from barely perceptible detail to the largest dimensions of tonal form, manifesting itself in subtly new forms at each stage of its development is, I believe, one of Mendelssohn’s most impressive achievements, one that seems to demand consideration in the exuberantly organic terms of Romantic creative theory. Indeed, Mendelssohn’s transformative methods are perhaps best understood in terms of the conception of botanical metamorphosis propounded by Goethe in his Versuch, die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären

(1790).

26

“Everything is leaf,” Goethe had written. The plant develops itself – both in form and function – through alternating stages of expansion and contraction of the embryonic leaf-forms already present in the germinated seed. In the whole as in the smallest detail, the plant manifests itself as transformed realizations of the

leaf that is its origin and its defining characteristic. The aesthetic correlate had already been expressed in Carl Philipp Moritz’s Über die bildende Nachahmung des Schönen

(1788): “a work is not put together

from without

, it is unfolded

from within. One

thought embodied in several forms.”

27

The seeds of the E![]() major/C minor confrontation that colors all of op. 12 lie, nearly concealed, in the opening measures of the first movement but come to thoroughly unexpected, but logically grounded fruition in the formal and expressive turmoil of the finale. A letter written in 1828 indicates how central this idea was to Mendelssohn’s musical thinking at this time (the work under discussion is Beethoven’s recently published String Quartet in C

major/C minor confrontation that colors all of op. 12 lie, nearly concealed, in the opening measures of the first movement but come to thoroughly unexpected, but logically grounded fruition in the formal and expressive turmoil of the finale. A letter written in 1828 indicates how central this idea was to Mendelssohn’s musical thinking at this time (the work under discussion is Beethoven’s recently published String Quartet in C![]() minor op. 131):

minor op. 131):

You see, that is one of my points! The relation of all 4 or 3 or 2 or 1 movements of a sonata to the others and to the parts, so that from the very beginning, and throughout the work, one knows its secret (so when the unadorned D major reappears, the 2 notes go straight to my heart); it must be so in music. 28

The final page of op. 12, too, goes straight to the heart, although the plot – the dynamic sequence of events – through which the composer leads us there may seem unpersuasive and overwrought, its secret, intimated from the very beginning and woven through all four movements, never quite measuring up to its emotional aspirations. 29 The problem is not unique to op. 12, and the inability of his most sympathetic listeners to recognize the “one thought” embodied over the whole course of each of his extended works vexed the composer greatly. In the same letter to his friend Adolf Lindblad, Mendelssohn wrote of his own op. 13 that

many people have already heard it, but has it ever occurred to any of them (my sister excepted, along with Rietz and also Marx) to see a whole in it? One praises the Intermezzo, another this, another that. Pfui to all of them! 30

In a roughly contemporary letter, Mendelssohn puts up an oddly half-hearted defense of the work against his father’s breathtakingly heavy-handed criticism:

You seem to mock me about my A minor Quartet, when you say that you have had to rack your brain trying to figure out what the composer was thinking about in some works, and it turned out that he hadn’t been thinking about anything at all. I must defend the work, since it is very dear to me; its effect depends too much on the performance, though. 31

This almost universal lack of comprehension – which surely could not be solely a product of inadequate performance – clearly troubled the young composer. The appeals to religious sentiment that begin to crop up in his works around this time – the Fugue in E minor (1827; published in 1837 as op. 35) or, staked out in grandiose biographical and historical dimensions in the ambitious cyclic and programmatic design of the “Reformation” Symphony (1831), and later in the finale of the Piano Trio in C minor op. 66 (1845), or the evocations of civic ritual – in the last pages of the Overture, Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt op. 27 (1828), or the “Scottish” Symphony (begun in 1829; published in 1843) – might well be understood as attempts both to render the untranslatable force with which musical facts go straight to the heart manifest and comprehensible – especially to the growing nineteenth-century lay audience – and at the same time to endow a work’s expressive “secret” with an unimpeachable emotional authority that would render questions of motivation moot.

Those questions, which invariably become more pressing as the emotional stakes are raised, tend to cluster around issues of closure on the largest scale. If the high-Classical progression from complexity in the first movement to a relatively lower level of intensity in the finale – the design achieved so brilliantly in Mendelssohn’s op. 18 – had come to seem stiffly academic and overly architectural, formal patterns merely “put together from without,” the thrilling, explicitly cyclic and implicitly narrative trajectories of Beethoven’s most characteristically “Beethovenian” works – the Fifth and Ninth Symphonies, for example – offered models as seductively attractive as they were fundamentally unrepeatable. It is at once one of Mendelssohn’s signal accomplishments and one of the more unsettling characteristics of his style that his greatest cyclic designs effect a compromise between the Classical progression of loosely related movements and Beethoven’s epically expressive plots; the return of the Scherzo in the Finale of the Octet, for example, owes at least some of its brilliant and magical wit to the fact that it operates at an exuberant but unabashedly lower level of expressive intensity than its obvious model, the high drama of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

It is not surprising, then, that one of the most successful of these compromises shapes one of Mendelssohn’s most effervescent conceptions, the Piano Concerto in G minor op. 25 (1831). Mercer-Taylor has written perceptively of the first movement’s most striking deviations from Classical concerto procedures: the elimination of the double exposition and the page of skittish virtuosity that stands in its place; and later, the drastically foreshortened recapitulation, where the orchestra barely has a chance to mention the main theme before the soloist interrupts with the lyric second theme. In particular, he is struck by the cumulative effect these maneuvers produce – an impression that the soloist “refuses to be bothered by any sense of responsibility to the principal theme around which the whole musical structure was to be organized” – suggesting that this might reflect the composer’s own “very serious anxieties concerning the insidious (as he saw it) impact of empty virtuosity on contemporary concert life.” 32

I would suggest that the work’s “secret” – its single thought – does, indeed, concern the relation of soloist and orchestra, and the principal theme of the first movement stands at its core. But the dynamic sequence through which it discloses itself is not completed within the first movement; it is a story that takes three explicitly interconnected movements to tell, and its organization represents one of the composer’s most satisfying cyclic designs. It will prove to be less about overcoming virtuosity than about justifying virtuosity as the agent of resolution in that design.

The gist of the story is simple enough: it involves the eminently Classical confrontation of the minor and major modes of the tonic, pivoting, of course, on the relation between B![]() and B

and B![]() , and played out in a sequence moving from the instability and gestural expressivity of the first movement’s G minor to the unbuttoned exuberance of the finale’s G major. What is new and uniquely Mendelssohnian is the unexpectedly rich – yet clearly delineated – harmonic language in which that confrontation takes place, the delicate play of inflectional relations it entails, and the masterful thematic and expressive design through which the story is articulated. All of the work’s themes can be traced back more or less directly to the upward rush of the orchestra’s brief introduction, which already in its second bar juxtaposes the minor and major thirds, B

, and played out in a sequence moving from the instability and gestural expressivity of the first movement’s G minor to the unbuttoned exuberance of the finale’s G major. What is new and uniquely Mendelssohnian is the unexpectedly rich – yet clearly delineated – harmonic language in which that confrontation takes place, the delicate play of inflectional relations it entails, and the masterful thematic and expressive design through which the story is articulated. All of the work’s themes can be traced back more or less directly to the upward rush of the orchestra’s brief introduction, which already in its second bar juxtaposes the minor and major thirds, B![]() and B

and B![]() . The downward plunge of the first movement’s principal theme is simply an inversion of this ascent, draped over a rhythmic diminution of mm. 1–3. The lyric second theme, first heard in the piano in B

. The downward plunge of the first movement’s principal theme is simply an inversion of this ascent, draped over a rhythmic diminution of mm. 1–3. The lyric second theme, first heard in the piano in B![]() major, combines versions of these ascending and descending motions in an expressive line – littered with performance directions – that can only maintain the major mode for four bars before falling into B

major, combines versions of these ascending and descending motions in an expressive line – littered with performance directions – that can only maintain the major mode for four bars before falling into B![]() minor in what might appear to be an example of what Tovey took to be the composer’s inability to tell major from minor (the same instability within the second theme is central to the cyclic design of the contemporaneous “Reformation” Symphony).

33

A few moments later the harmony drifts even farther afield, drawn to B

minor in what might appear to be an example of what Tovey took to be the composer’s inability to tell major from minor (the same instability within the second theme is central to the cyclic design of the contemporaneous “Reformation” Symphony).

33

A few moments later the harmony drifts even farther afield, drawn to B![]() ’s own minor third for an idyllic episode in the thoroughly unlikely – and implausibly un-Mendelssohnian – realm of D

’s own minor third for an idyllic episode in the thoroughly unlikely – and implausibly un-Mendelssohnian – realm of D![]() major, the major mode of the key a tritone from G minor, the overall tonic (mm. 79ff.).

major, the major mode of the key a tritone from G minor, the overall tonic (mm. 79ff.).

The premature intrusion of this almost schizophrenically expressive lyric second theme just after the opening of the recapitulation does, indeed, suggest that the soloist has little use for the orchestra’s grimly forthright main theme and its virtuoso bluster; but even the second theme is severely curtailed, its espressivo musings drifting quickly into “virtuoso ambling” that never manages to escape G minor.

In fact, G major doesn’t make an appearance until the transition leading into the second movement, where its major third, B![]() , is immediately taken as V of E major, the key of the Andante. This movement, lying somewhere between extended song, rondo, and a loose set of variations on a theme that is itself a variant of the second theme of the first movement, achieves a lyric climax of rapturous textural refinement, piano

and tranquillo

, in B major – an ecstatic celebration of B

, is immediately taken as V of E major, the key of the Andante. This movement, lying somewhere between extended song, rondo, and a loose set of variations on a theme that is itself a variant of the second theme of the first movement, achieves a lyric climax of rapturous textural refinement, piano

and tranquillo

, in B major – an ecstatic celebration of B![]() in a context equally visionary and ephemeral.

in a context equally visionary and ephemeral.

The soloist reverts to flashing outbursts of virtuosity in the transition that storms in on the final cadence of the second movement, but this time its goal proves to be emphatically thematic and structurally central: the passage culminates in the long anticipated establishment of G major, marked by an exuberant, fully (indeed, elaborately) formed theme beginning on the major third, B![]() (Example 5.5a

).

(Example 5.5a

).

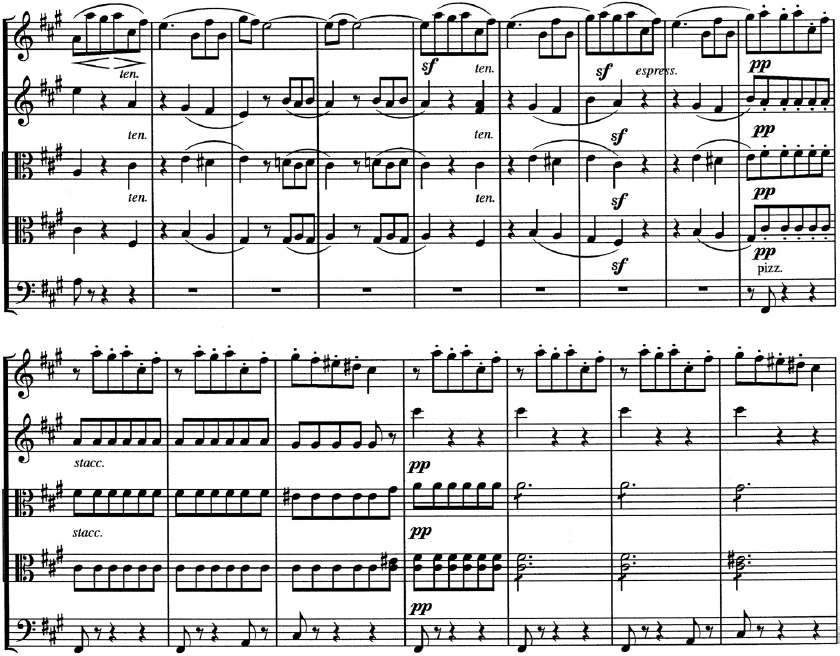

Example 5.5 Piano Concerto in G minor op. 25, movement 3

(a) mm. 40–47

(b) mm. 71–77

This new theme is, in fact, simply a G major version of the principal theme of the first movement: the piano’s initial b![]() ′″ emphatically trumps the b

′″ emphatically trumps the b![]() ″ proposed by the orchestra in the first movement; the line also reworks the

gestures of the second theme of the first movement. The piano, having at last established the “real” version of the principal theme – the secret only fleetingly glimpsed in the opening bars of the first movement, seems reluctant to relinquish its new-found form-creating power, moving on to another new theme which will dominate the finale, manically expounding that secret – the resolution of B

″ proposed by the orchestra in the first movement; the line also reworks the

gestures of the second theme of the first movement. The piano, having at last established the “real” version of the principal theme – the secret only fleetingly glimpsed in the opening bars of the first movement, seems reluctant to relinquish its new-found form-creating power, moving on to another new theme which will dominate the finale, manically expounding that secret – the resolution of B![]() to B

to B![]() (now heard in a neighbor-note motion, B–A

(now heard in a neighbor-note motion, B–A![]() –B) – in its swirling figuration (Example 5.5b

).

–B) – in its swirling figuration (Example 5.5b

).

Tovey claimed that in the suppression of the double exposition “Mendelssohn may truthfully be said to have destroyed the classical concerto form.” But he admitted that, at least in the case of the Violin Concerto, the composer was “not so much evading a classical problem as producing a new if distinctly lighter art-form.” 34 In its modest and distinctly accessible way op. 25 had already established that new form with much of the rigor and energy that marks his finest early works.

In op. 25 Mendelssohn reconstitutes what Tovey called “the primary fact . . . of concerto style . . . that the form is adapted to render the best effect expressible by opposed and unequal masses of instruments or voices.” 35 In op. 25, tonal resolution, realized in terms of a delicate but surprisingly rich network of chromatic inflectional transformations, motivic process, and the dramatic form-defining role of the soloist in its confrontation with the massed forces of the orchestra are all expanded beyond the formal processes of the first movement, coordinated within a multi-movement cyclic process spinning out a single, immediately comprehensible expressive trajectory from the abrupt juxtapositions of the opening of the first movement to the joyous exuberance of the Finale.

That this new art form remains true both to its heritage and to its present – with neither condescension nor provocation – is, of course, the signal attribute of Mendelssohn’s often elusive progressivism. Like Mozart writing to his father about his own piano concertos, Mendelssohn could say of op. 25, as of all his finest works, that it struck

a happy medium between what is too easy and too difficult; they are very brilliant, pleasing to the ear, and natural, without being vapid. There are passages here and there from which connoisseurs alone can derive satisfaction; but these passages are written in such a way that the less learned cannot fail to be pleased though without knowing why. 36

Even today, we continue, learned connoisseurs and general audience alike, to be pleased by Mendelssohn’s finest works, all too often without quite knowing why.