In the case of a composer like Mendelssohn, it is not easy to claim that a certain part of his oeuvre is more important than another: it was his avowed goal to be active and successful in as many different musical genres as possible, and – with the single exception of opera – he achieved just this. Nevertheless, it can be said that the mature chamber works of Mendelssohn rank not only among the finest works of the composer, but among those achievements of his that were of lasting importance for the entire century. The techniques of motivic combination, derivation, juxtaposition, and interplay that characterize his mature chamber style, which arose from Mendelssohn’s fascination with the music of both Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig Beethoven, exercised a considerable influence on nineteenth-century instrumental music in general; it is hardly an exaggeration to claim that the technique of “developing variation” has its roots precisely here. Furthermore, their sheer beauty and highly idiomatic writing for all instruments have secured a place in the performance repertoire and the recording market for at least some of these works – particularly the two piano trios and some of the string quartets.

The chamber music can be divided up – roughly as Mendelssohn’s work as a whole can be – into three phases of differing length and importance: a number of youthful works ranging from the first attempts at the age of eleven (in 1820) up to the first publications in 1824; the works of the “first maturity,” beginning with the third Piano Quartet op. 3 and the Octet op. 20 (both 1825) and ending around 1830; after a rather long period in which no chamber music was written (with the exception of a few occasional works, like the two Konzertstücke for basset-horn composed in 1832/33 for the clarinettist Carl Bärmann) comes the period of full maturity, bringing forth works like the Quartets op. 44 (1837–38) and the two Piano Trios opp. 49 (1839) and 66 (1845).

Among Mendelssohn’s first attempts at composition, transmitted in the exercise book he prepared under the supervision of Carl Friedrich Zelter in or around 1820, a small number of chamber works are already extant among counterpoint exercises, chorale settings, and piano pieces. All of them are scored for violin and piano, reflecting the practical situation in which Felix would play the top part on the violin and Zelter would accompany on the piano. 1 Some are three-part fugues in the style of Johann Sebastian Bach; we also find two sets of variations reminiscent of Haydn, although, characteristically, with rather more contrapuntal writing than would be considered typical for the older master. The two short monothematic movements (also in imitative counterpoint) that round off the small group of “chamber music” pieces in the exercise book are in fact more reminiscent – in form as well as in texture – of bipartite movements in the Baroque trio sonata tradition than of “monothematic sonata form” as R. Larry Todd rather generously classifies them. 2

A number of fully developed multi-movement chamber works were also written for Zelter’s lessons. The earliest, of May 1820, is a piano trio in C minor, with the unusual scoring of viola instead of violoncello (possibly because of the lack of a cello player in the family: the youngest son of the family, Paul – who was to fill that position in later years – had only been born in 1813 and could hardly have been expected to participate just yet). Over the course of the next months, two sonatas followed, again for violin and piano; after that, the production of chamber music largely ceased. As in all other genres, Zelter did not hold his pupil to abstract “rules,” but encouraged him to practice certain textures and styles through the repeated composition of pieces; 3 later, in the “lessons” Mendelssohn himself held as teacher of the Conservatory of Music in Leipzig, he used the same method. 4 Hence, the “practice works” of the early 1820s usually come in tight groups and in a certain style; the “chamber music phase” of 1820 is followed by string symphonies and sacred vocal music in 1821–22. Only a set of twelve fugues for string quartet and a piano quartet in D minor is extant from 1821, only the Piano Quartet op. 1 in C minor from October of 1822.

With the three Piano Quartets opp. 1–3 and the Violin Sonata op. 4, Mendelssohn reached a new stage in his creative output. This manifests itself externally in the fact that the ever self-critical composer and his equally critical mentors – his father Abraham and, of course, Zelter – now felt that the time had come to step outside the self-contained world of private study and semi-public performance in the family-owned Gartenhaus and to introduce himself to the general public through carefully planned series of works in important genres. It is certainly no accident that this first step was taken in the form of chamber works; nor is it accidental that, before op. 10 (the opera The Marriage of Camacho ), all published works were not for the truly “public” venues of church, stage and concert hall, but for smaller contexts: after the four chamber works, opp. 5 to 7 are for piano solo, opp. 8 and 9 are songs.

Chamber music, then, would have been considered a prudent and time-tested choice for an “opus 1.” But why piano quartets? In fact, the genre could be considered the ideal point of departure for the career of a young composer-pianist. Its piano part – exacting, but not too extroverted – gave Mendelssohn the opportunity to prove himself as a performer without lowering himself to the status of a mere virtuoso; at the same time, the quartet genre appealed to the tradition of “serious” chamber music with all its compositional rigor, and the added possibility of showing one’s ability as a contrapuntist. And this particular genre, having as its only famous predecessors the two works by Mozart (K. 478 and K. 493), was not as overburdened with tradition as was the string quartet (which might otherwise have appeared to be the more natural starting point) where Beethoven loomed as the seemingly insuperable precursor.

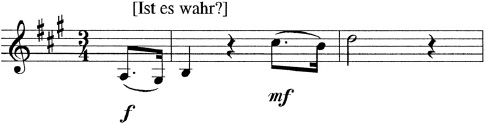

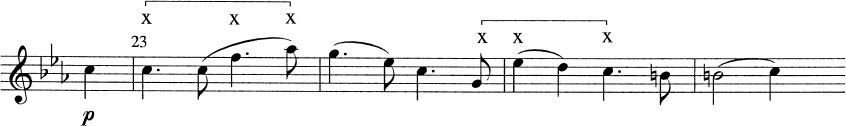

Not surprisingly, the three piano quartets could be called “conservative,” with formal and thematic structures clearly delineated, the piano and the three string instruments forming separate entities treated in an “antiphonal” manner. Particularly the first two quartets (finished in October of 1822 and May of 1823) point back to the late eighteenth century with their light texture and galant piano figurations. All three quartets are in four movements and, somewhat unusually, all in minor keys (C minor, F minor, and B minor). But even at this early stage, individual traits begin to emerge, in op. 1 most strikingly in the “elfin” perpetuum mobile piano figurations of the Scherzo. In the Finale of op. 2, this penchant for continuous motion leads to an early manifestation of what was to become one of Mendelssohn’s trademarks: the superimposition of a new theme over one introduced earlier. The restless eighth-note theme of the first group is reused as accompaniment (in the violin) for the cantabile second-group theme in the viola (see Example 8.1 ); in the recapitulation, the same combination even appears in double counterpoint with the cantabile tune sounding below the first theme. This method of combining two seemingly independent lines (originating in the counterpoint lessons with Zelter) 5 demonstrates Mendelssohn’s predilection for contrapuntal devices that are at once simple and complex: simple on the surface, in the sense that they are clearly audible and comprehensible; complex in the sense that the two parts fit together in a fashion that is not at all apparent when hearing them independently. Another innovation of op. 2 is the substitution of the Scherzo movement with an “Intermezzo” of suitably light character, but without the standard structural and rhythmical features of the traditional tripartite form in triple meter based on the minuet.

Example 8.1 Piano Quartet op. 2 in F minor, finale, mm. 59–68

The Third Quartet op. 3, of January 1825, shows richer sonorities and a better integration of the piano and string parts, while raising the integration of form and textures to a new level. In the first movement, the theme of the second group (mm. 111–17) is derived from a countersubject in the piano to the continuation of the first theme in the strings (mm. 24ff.); at first a simple, sequentially repeated chordal figure, it develops into a chorale-like melody. The first themes of all four movements are related in motivic substance through the opening gesture of a rising second followed by two or more falling seconds. The perpetuum mobile Scherzo is given more pronounced contours than in op. 1; Goethe himself, for whom Mendelssohn had played it during his second visit to Weimar on 25 May 1825, noted the “elfin” poetic association:

The Allegro, on the other hand, had character. This eternal whirling and turning brought to my imagination the witches’ dances on the Blocksberg, and thus I had a concept after all to associate with this wondrous music. 6

One last work among the youthful compositions deserves mention: the Piano Sextet in D major, finished in May of 1824 and published posthumously in 1868 as op. 110. The unusual addition of a double bass was apparently intended to add sonority to the established piano quintet texture. 7 Werner’s classification of the work as “a little piano concerto” 8 seems somewhat exaggerated; the piano part demonstrates considerable, but by no means excessive, virtuosity – no more than the later piano quartets and trios. At the same time, there is too much thematic dialogue between piano and strings, and independence in the voice-leading of the string instruments, for the work to be classified as anything but chamber music. Formally the sextet is the first composition to introduce a device which was to become almost standard for Mendelssohn’s instrumental music of the later 1820s: the theme of the “Minuetto” (really more a Scherzo) is quoted verbatim over a length of thirty-one bars in the coda of the finale, including a change of time signature from common time to 6/8. The intention to unify the four-movement cycle through thematic references into a “poetic” whole is as obvious here as is the model of Beethoven.

The Third Piano Quartet, with its development of a number of techniques that were to become standard procedure in Mendelssohn’s later chamber music, could be perceived as a logical stage in his development as a composer. The String Octet (op. 20) of the same year is anything but logical. At first sight, it appears to be in almost all aspects – character, texture, formal planning, sheer size – a radical departure from anything the composer (or, for that matter, anybody else) had attempted in chamber music. Its texture is not – as in earlier works for eight strings – that of a polychoral “double quartet,” but a true eight-voice composition in which the sixteen-year-old composer explored all possible constellations. Frequently the first violin part (written for Mendelssohn’s friend Eduard Rietz, the violinist whose career was cut short by his premature death at the age of twenty-nine in 1832) has concertante passages of staggering virtuosity, with varying accompaniment; but virtually no other possible combination of instruments is left unexplored, in solo texture, parallel movement in thirds, sixths and octaves, imitative counterpoint, antiphonal treatment of high against low voices, and so forth.

The strategies of thematic and formal unity found in the piano quartets are apparent in the octet as well, though superseded by the heightened possibilities of contrast and variation in the eight-voice medium. The texture varies between full orchestral treatment (as in the very first bars) and intricate counterpoint; the thematic development in particular, although embedded in a process outwardly full of drama and contrast, abounds with motivic relationships and derivations. In the exposition of the first movement alone, the following elements can be listed: 9

m. 1: arpeggiated theme 1 in the top voice

m. 9: new motive in the violins, accompanied by theme 1 in the two cellos, followed by a falling eighth-note figure in the violins

m. 16: prolongation of the falling eighth-note figure

m. 21: “new” sixteenth-note motive (but really an extension of the rising arpeggiations of theme 1, answered by falling quarter-note figure, derived from the eighth-note figure in mm. 16ff.)

m. 25: development of a segment of the sixteenth-note motive

m. 37: re-entry of theme 1

m. 45: like m. 9, but with theme 1 in inversion

m. 52: like m. 25, followed by prolongation of theme 1

m. 68: “second theme” derived from the quarter-note figure in m. 22 (in inversion) with interspersed segements from theme 1

m. 75: “new” motive derived from the last four eighth-notes of “second theme”

m. 77: like m. 68

m. 84: like m. 75, with prolongation

m. 88: sixteenth-note motive from m. 21 in inversion – which at the same time turns out to be a rhythmic extension of the falling eighth-note motive derived from the “second theme” in mm. 75 and 84! The arpeggiated eighth-note accompaniment is derived from theme 1

m. 96: “second theme” accompanied by sixteenth-note scales

m. 102: scales derived from inverted sixteenth-note motive (m. 88), segment of theme 1.

After so much working and reworking of the thematic material, there does not seem much left for the composer to do in the development – a general trait in Mendelssohn’s chamber music which was to become even more pronounced in the later works. Hence, the development is more concerned with texture and dynamics than with themes: The head motive of the first theme is juxtaposed with itself in four texturally separated groups (violin 1/violins 2, 3, 4/violas/cellos); the sixteenth-note motive is heard in fortissimo instead of piano ; the second theme is augmented and reduced dynamically and texturally to create a sense of almost complete stasis, which in turn makes it possible for the composer to engineer one of the most impressive – although totally unthematic – climaxes in all of chamber music, from two practically silent, immobile voices (viola 1 and cello 2) in m. 200 to virtuosic, sempre ff sixteenth-note scales in eight-voice unison in m. 218.

The slow movement can be analyzed in two different ways: first, as a modified sonata form with a development based exclusively on the second (transitory) theme, an abridged recapitulation – missing the entire first group – and a balancing coda reintroducing precisely that first theme;

second, as a binary form with two sections of almost the same length, the first (mm. 1–53) moving from the tonic C minor to the parallel key E![]() major and the second (mm. 54–102) modulating back to C minor, the thematic groups being rearranged from A–B–C in the first section to B–C–A in the second.

major and the second (mm. 54–102) modulating back to C minor, the thematic groups being rearranged from A–B–C in the first section to B–C–A in the second.

After the ethereal sonority of the slow movement, the Scherzo is even more innovative in terms of atmosphere. The first attempts to create the famous Mendelssohnian “elfin” sound had been through piano figurations in the early chamber music; in the eight-voice, all-string setting, the texture comes entirely into its own, in rapid eighth- and sixteenth-note motion, pianissimo almost throughout. Unlike almost every other composition by Mendelssohn, the movement appears in the autograph score without any corrections; obviously, it was written in a moment of complete inspiration. According to Mendelssohn’s sister Fanny, the music was inspired by the four closing lines from the Walpurgis Night’s Dream of Goethe’s Faust :

Cloud and mist drift off with speed,

Aloft ’tis brighter growing.

Breeze in leaves and wind in reed,

And all away is blowing. 10

Fanny elaborates further on her brother’s intentions concerning the movement:

The whole piece is to be played staccato and pianissimo, the tremulandos entering every now and then, the trills passing away with the quickness of lightning; everything is new and strange and at the same time most insinuating and pleasing. One feels near the world of spirits, carried away in the air, half inclined to snatch up a broomstick and follow the aerial procession. At the end the first violin takes a flight with a feather-like lightness – and all away is blowing. 11

The finale takes the perpetuum mobile

idea and turns it around completely. The movement opens with an eight-voice fugato of a theme entirely in eighth notes – and the eighth-note motion reigns, with few exceptions, throughout. The idea of a perpetuum mobile

fugue is once again inspired by Beethoven, in this case by the finale of the String Quartet op. 59 no. 3, but taken to further extremes and made more powerful through the participation of twice as many instruments. It could be said that the perpetuum mobile

not only is the driving force of the movement, but supersedes all other aspects. Even the form – a modified rondo – is subordinate to it, as the otherwise typical elements (change of pace and thematic contrast) are lacking. What themes there are in addition to the eighth-note motion do not replace it, but are superimposed onto it; from m. 321 onwards (little more

than three quarters through the movement), E![]() major is reached incontrovertibly, and the rest functions as one gigantic coda. As in the sextet, the main theme of the Scherzo is restated in the Finale (mm. 273–313), although this time integrated into the texture of the movement.

major is reached incontrovertibly, and the rest functions as one gigantic coda. As in the sextet, the main theme of the Scherzo is restated in the Finale (mm. 273–313), although this time integrated into the texture of the movement.

The one genre, however, that Mendelssohn had largely eschewed up to this point – or, to put it more bluntly, avoided – was the string quartet.

12

Since the works of Haydn and Mozart, the string quartet had been considered the pinnacle of achievement in chamber music; contemporary music theory considered the four-voice texture the ideal and perfection of “learned” polyphonic writing. The fact that all four instruments were equal in timbre – at least in principle – resulted in the commonplace most famously expressed by Goethe, that in the string quartet “one could hear four reasonable people in conversation.”

13

A number of Mendelssohn’s predecessors and contemporaries (including Ignaz Pleyel and Franz Krommer) had introduced themselves to the public with a string quartet or group of string quartets precisely to stake their claim as composers of “serious” music. Mendelssohn’s personal route toward string quartets, however, was full of detours. A set of fugues for string quartet is extant from the spring of 1821 – another instance of the “learnedness” of the four-voice texture – and in 1823, we find a complete four-movement quartet in E![]() major. This work, however, has all the qualities of a “study composition,” lacking the thematic and textural innovations introduced in the piano quartets.

major. This work, however, has all the qualities of a “study composition,” lacking the thematic and textural innovations introduced in the piano quartets.

Even after the composition of the octet, Mendelssohn’s approach to the quartet was an indirect one: the first chamber composition to follow was the String Quintet op. 18 written in the spring of 1826. Its scoring, with two violas, is that of Mozart, but Mozart does not appear to be the main model. The textural juxtaposition of two violins versus two violas so common in Mozart is largely absent; on the contrary, many different textures are used, as in the octet, with a clear predominance of the first violin as solo instrument. The influence of Beethoven is not directly obvious, particularly as his C major String Quintet (op. 29 of 1801) is very different in character and level of sophistication, with its almost divertimento-like tone and its predominantly homophonic textures. Mendelssohn, on the other hand, attempts to write a chamber work with all the sophistication of a quartet. In its first version, the quintet consisted of four fast movements (the Intermezzo , written on occasion of the death of Eduard Rietz on 22 January 1832, replaced an original Allegretto as second movement), and the Scherzo is a highly unusual “elfin fugue.”

With the two quartets op. 12 in E![]() major and op. 13 in A minor (the first written in 1829, the second in 1827, but both published in 1830 in reverse order of composition), the compositional and artistic progress of the preceding years – manifested most of all in the octet – is incorporated

into the quintessential chamber music genre. Both works very clearly show the influence of Beethoven; indeed, they are modeled on the most “progressive” works of the older master, the very last quartets. Mendelssohn’s father Abraham did not think much of Beethoven, but was broad-minded enough to acquire all current works for his children directly after they were published, and both Felix and his sister Fanny were thrilled with what they found. Particularly telling is a letter Felix wrote to his friend, the Swedish composer Adolf Fredrik Lindblad, in February of 1828, shortly after finishing his own E

major and op. 13 in A minor (the first written in 1829, the second in 1827, but both published in 1830 in reverse order of composition), the compositional and artistic progress of the preceding years – manifested most of all in the octet – is incorporated

into the quintessential chamber music genre. Both works very clearly show the influence of Beethoven; indeed, they are modeled on the most “progressive” works of the older master, the very last quartets. Mendelssohn’s father Abraham did not think much of Beethoven, but was broad-minded enough to acquire all current works for his children directly after they were published, and both Felix and his sister Fanny were thrilled with what they found. Particularly telling is a letter Felix wrote to his friend, the Swedish composer Adolf Fredrik Lindblad, in February of 1828, shortly after finishing his own E![]() major quartet, a work clearly modeled upon Beethoven’s op. 132 (which Schlesinger in Berlin had brought out barely a month previously!):

major quartet, a work clearly modeled upon Beethoven’s op. 132 (which Schlesinger in Berlin had brought out barely a month previously!):

Have you seen his new quartet in B![]() major [op. 130]? And that in C

major [op. 130]? And that in C![]() minor [op. 131]? Get to know them, please. The piece in B

minor [op. 131]? Get to know them, please. The piece in B![]() contains a cavatina in E

contains a cavatina in E![]() where the first violin sings the whole time, and the world sings along . . . The piece in C

where the first violin sings the whole time, and the world sings along . . . The piece in C![]() has another one of these transitions, the introduction is a fugue!! It closes very scarily in C

has another one of these transitions, the introduction is a fugue!! It closes very scarily in C![]() major, all instruments play C

major, all instruments play C![]() ; and the next entry is in such a sweet D major (the next movement, that is), and such little ornamentation! You see, this is one of my points! The relationship of all 4 or 3 or 2 or 1 movements of one sonata to another and their parts, whose secret one can recognize at the very beginning through the simple existence of such a piece (because the mere beginning in D major, those two notes, make me tender-hearted), that must go into the music. Help me put it there!

14

; and the next entry is in such a sweet D major (the next movement, that is), and such little ornamentation! You see, this is one of my points! The relationship of all 4 or 3 or 2 or 1 movements of one sonata to another and their parts, whose secret one can recognize at the very beginning through the simple existence of such a piece (because the mere beginning in D major, those two notes, make me tender-hearted), that must go into the music. Help me put it there!

14

As in other “Beethovenian” works, such as the two Piano Sonatas op. 6 (1826) and op. 106 (1827), Mendelssohn paid homage in three different ways. First, all works begin with a direct quotation or allusion to a recent work of the older composer. The A minor Quartet begins like Beethoven’s op. 132, the E![]() major Quartet like the op. 74 Quartet of 1809. Second, the linking of all four movement through motivic references becomes even more pronounced. This technique is of course present in a number of earlier compositions by Beethoven, but increases in importance in the late works, most prominently in op. 131, which was specifically mentioned by Mendelssohn in that context. In his own quartets, op. 12 is remarkable primarily through the recurrence of the second theme from the first movement not once but twice in the finale, with a complete break in texture and rhythm both times.

major Quartet like the op. 74 Quartet of 1809. Second, the linking of all four movement through motivic references becomes even more pronounced. This technique is of course present in a number of earlier compositions by Beethoven, but increases in importance in the late works, most prominently in op. 131, which was specifically mentioned by Mendelssohn in that context. In his own quartets, op. 12 is remarkable primarily through the recurrence of the second theme from the first movement not once but twice in the finale, with a complete break in texture and rhythm both times.

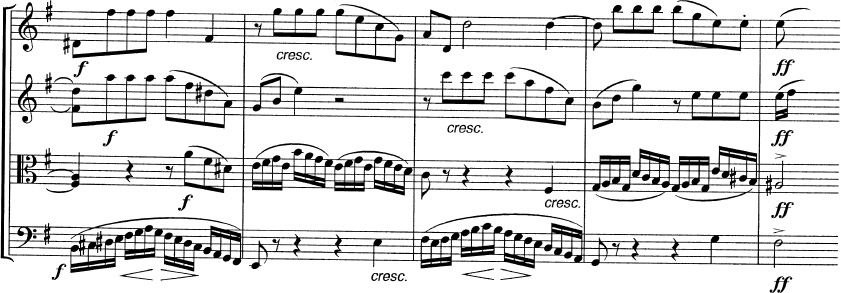

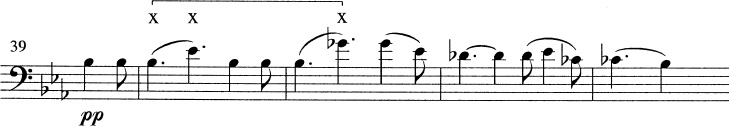

The A minor Quartet combines this quest for motivic unity with the third device taken from Beethoven: the introduction of “poetic meaning” into the string quartet. Extramusical elements like tone painting, poetic titles, or programmes had so far been almost completely absent from the string quartet, embodying as it did “pure,” “absolute” music; only Beethoven’s “Heiliger Dankgesang” from op. 132, or “Der schwer gefasste Entschluss” from op. 135, had broken with this tradition. Mendelssohn obviously took these works as his inspiration, but went a step further and placed an entire song of his own composition at the beginning of op. 13, with the title “Ist es wahr?” (“Is it true?”) and the designation “Thema.” The opening motive of that song alludes directly to Beethoven’s “Der schwer gefasste Entschluss” (“Muss es sein”) in rhythmical and melodic contour (Example 8.2a ). It is introduced towards the end of the introduction to the first movement; an extended quotation from the song closes out the finale, thus giving the answer to the question posed at the beginning: “Was ich fühle, das begreift nur, die es mitfühlt, und die treu mir ewig bleibt” (“What I am feeling is only understood by her who feels with me and who always remains true to me”). Thus, the technique of motivic unity simultaneously becomes a device of poetic unity. Moreover, the motive reoccurs in the main theme of the first movement (Example 8.2b ), a variant thereof and later its inversion in movement 2 (8.2c and 8.2d); this inversion becomes the first theme of the Intermezzo (8.2e) and a fugato theme in the development of the Finale (8.2f).

Example 8.2 String Quartet op. 13 in A minor

(a) first movement, mm. 13–15 (violin 1)

(b) first movement, mm. 26–28 (violin 1)

(c) second movement, mm. 1–3 (violin 1)

(d) second movement, mm. 20–22 (viola)

(e) third movement, mm. 1–4 (violin 1)

(f) fourth movement, mm. 164–68 (viola)

The only area in which Mendelssohn remains on the conservative side of Beethoven is in his treatment of harmony. Where Beethoven pushed tonality to its outer limits, particularly in the C![]() minor Quartet op. 131, Mendelssohn remains firmly grounded in dominant–tonic relationships, daring as individual chord progressions may sound. At the same time, both works are unmistakably “Mendelssohnian.” They retain the vigor of motion familiar from octet and quintet, most noticeably in the perpetuum mobile

finale of op. 12 and in the dramatic opening movement of op. 13. The formal patterns are manifold, as always, from the sonata-rondo first movement of op. 12 to the Canzonetta

of op. 12 and the Intermezzo

of op. 13, both modifying the traditional Scherzo type considerably; their middle sections also modify the by now familiar “elfin Scherzo.” Both finale movements are highly original variants of sonata form combined with recitative-like and cyclical elements as mentioned above; they sum up the entire four-movement cycle. The technique of thematic superimposition recurs in the first movement of op. 13, where two seemingly separate motives are presented in mm. 19 and 24 respectively, then synchronized in m. 42. Perhaps most importantly, however, the two quartets are pure specimens of Mendelssohn’s ability to write “melodic counterpoint.” The polyphonic ideal manifests itself in innumerable imitative passages and contrapuntal inner voices – the entire first movement of op. 13 has few passages that are not imitative in two or more parts. Particularly Mendelssohnian are combinations of imitative counterpoint with lyrical passages resembling some of his later Songs without Words

, as in the slow movement of the same work, or with “elfin Scherzo” music, as in the Intermezzo

.

minor Quartet op. 131, Mendelssohn remains firmly grounded in dominant–tonic relationships, daring as individual chord progressions may sound. At the same time, both works are unmistakably “Mendelssohnian.” They retain the vigor of motion familiar from octet and quintet, most noticeably in the perpetuum mobile

finale of op. 12 and in the dramatic opening movement of op. 13. The formal patterns are manifold, as always, from the sonata-rondo first movement of op. 12 to the Canzonetta

of op. 12 and the Intermezzo

of op. 13, both modifying the traditional Scherzo type considerably; their middle sections also modify the by now familiar “elfin Scherzo.” Both finale movements are highly original variants of sonata form combined with recitative-like and cyclical elements as mentioned above; they sum up the entire four-movement cycle. The technique of thematic superimposition recurs in the first movement of op. 13, where two seemingly separate motives are presented in mm. 19 and 24 respectively, then synchronized in m. 42. Perhaps most importantly, however, the two quartets are pure specimens of Mendelssohn’s ability to write “melodic counterpoint.” The polyphonic ideal manifests itself in innumerable imitative passages and contrapuntal inner voices – the entire first movement of op. 13 has few passages that are not imitative in two or more parts. Particularly Mendelssohnian are combinations of imitative counterpoint with lyrical passages resembling some of his later Songs without Words

, as in the slow movement of the same work, or with “elfin Scherzo” music, as in the Intermezzo

.

The two “early” quartets opp. 12 and 13 have always been grouped among Mendelssohn’s uncontested masterpieces; their clear indebtedness to the late Beethoven quartets place them on the cutting edge of chamber music writing, and their – sometimes barely controlled – temperament, their novelty of texture and form, and their allusions to extra-musical content made it easy for music historians to integrate them into an over-arching concept of musical progress and into a Romantic ideal of “poetic” instrumental writing. Eric Werner concludes: “Indeed, had Mendelssohn been able to maintain the level of this quartet [the A minor], his name would stand in close proximity to that of a Mozart or Beethoven!” 15

After a long hiatus in chamber music production in the early 1830s – coinciding with a general creative crisis – the years after 1836 show Mendelssohn newly invigorated. And it is perhaps no accident that among the first important works to appear after 1836, a disproportionately large number are in chamber genres: the three String Quartets op. 44 (1837–38), the Cello Sonata op. 45 (1838), the unpublished Violin Sonata in F major (1838) and the Piano Trio op. 49 (1839). By now Mendelssohn shows the poise and self-assurance of the mature artist, and rather than taking detours through string quintet, octet, and piano quartet, he tackles the main traditions head on: string quartet, piano trio, accompanied solo sonata.

The first and greatest achievements of this period are the three String Quartets op. 44, written between summer of 1837 and summer of 1838, published in 1839. Though enthusiastically received by critics and audience alike on Mendelssohn’s time, they have not fared as well in the eyes of modern commentators. Eric Werner, who diagnoses an “artistic slump” in Mendelssohn’s creative output in the years between 1838 and 1844, states: “he becomes somewhat too smooth, and only his inborn taste and his technical mastery save him, in the following years, from sheer mediocrity.” 16 For Werner, the String Quartets op. 44 are prime exemplars for the “tranquil years” between 1837 and 1841. With Beethoven’s late works as his yardstick, Werner looks for contrast, struggle, strong emotions; and when he finds the quartets lacking in these, he states regretfully: “[a]s the Second Piano Concerto is far inferior to the First, so these quartets, as a whole, do not reach the heights of originality and inspiration of their forerunners opp. 12 and 13.” 17

However, Werner’s preoccupation with drama and contrast, as well as his entirely speculative assertion that it was his happy marriage with Cécile and the resulting “bourgeois” lifestyle that deflected Mendelssohn from the path of a “truly Romantic” composer, 18 tell us more about our modern views of what music history should be like than about the music and its composer. It is too simple to view the Quartets op. 44 as failures merely because they do not maintain the Beethovenian tradition of chamber music. Already in 1835, Fanny had written to her brother that

we were young precisely in the time of Beethoven’s last years, and it was only to be expected that we completely assimilated his manner, as it is so moving and impressive. But you have lived through it and written yourself through it. 19

According to Fanny, then, Felix had attained maturity precisely by having transcended Beethoven and having created something of his own. In fact, Mendelssohn was pursuing very specific – and very individual – goals in his mature quartets, goals that owe as much to his interpretation of the idea of a “conversation of four reasonable persons” as to his general ideas on thematic, formal, and poetic unity. Indeed gone are the direct references to Beethoven, gone are the extroverted exuberance and the formal experiments of the early quartets and the Octet. But as Friedhelm Krummacher puts it, “only from op. 44 onwards does Mendelssohn attain a completely individual model of sonata form. It is characterized not by drama and dialectic, but on the contrary by balance and reconciliation. Thematic contrasts are rounded off and subsumed in homogeneous situations, and latent connections of the thematic substance support a specific mediation between quasi-stationary sections.” 20

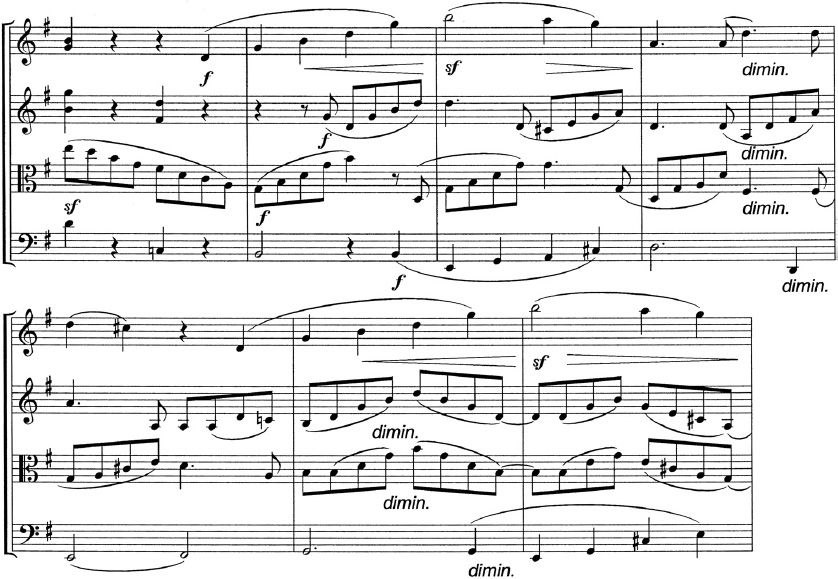

Indeed, thematic (and poetic) unity reach a new level in the quartets of op. 44 precisely by way of the composer’s decision to forgo the dramaturgy of contrast that is a supposed precondition of sonata form. This is best exemplified in the first movement of the E minor Quartet op. 44 no. 2, the earliest of the three works. Its first and second theme are both cantabile lines, similar in rhythm and phrasing if not in melody. A sixteenth-note motive that dominates most of the bridge passage between first and second group appears to form a sharp contrast; but it turns out that it is the accompaniment to a falling eighth-note figure which appears to be a variant of the continuation of the first theme, but really is the inverted diminution of that theme itself (see Examples 8.3a and 8.3b ). Towards the end of the exposition, this diminution even serves as accompaniment to the theme itself (Example 8.3c ). In the development, the possible permutations and combinations of the different related motives are explored further, the sixteenth notes now accompanying the first theme in its original form, the eighth-note version appearing in canon, serving as accompaniment to the recapitulation and subtly reverting back from the arpeggiated to the scalar form in which it first appeared in the exposition.

Example 8.3 String Quartet op. 44/2 in E minor, first movement

(a) mm. 1–5: first theme

(b) mm. 32–35

(c) mm. 83–89

Besides the “poetic unity” of the mature quartets thus attained through motivic relations, another aesthetic goal of the composer becomes apparent in op. 44. Almost without exception, the movements begin homophonically, usually in basic melody-plus-accompaniment texture with the first violin carrying the theme. In the first movements of op. 44 no. 1, the resulting texture is almost orchestral in character, with all accompanying voices in sixteenth-note tremolo. In op. 44 no. 2 as well, the themes are introduced in the same fashion before entering in the motivic interplay described above. This is in vivid contrast to the earlier chamber music where, especially in the fast movements, the themes are often treated contrapuntally right from the beginning. The reason for this changed manner of presentation is, in all likelihood, bound up with a contemporaneous change in Mendelssohn’s aesthetics. The composer had always been very keen on Bestimmtheit – clarity – in his instrumental music, in the sense that the ideal listener immediately understood the “meaning” of his music without requiring verbal explanations. 21 Over the course of his creative life, Mendelssohn had tried different methods to achieve such clarity, including literary or topographical references in the early orchestral works. In chamber music, where such “extra-musical” references were not part of the genre history, the “intra-musical” strategies of meaning described above (thematic quotes or cyclical construction) were to serve the same purpose.

Beginning in the mid-1830s, Mendelssohn began to place more importance on the presentation of the thematic material as such: “I want the ideas to be expressed more simply and more naturally, but to be conceived in a more complex and individual fashion,” he writes to Wilhelm von Boguslawski in 1834; 22 a good composer has to be able primarily “to clearly present his ideas and what he wants to express.” 23 Mendelssohn criticizes Bernhard Schüler’s overture Gnomen und Elfen primarily “because in many places, particularly in the beginning, but now and then elsewhere as well, I miss a marked musical shape, whose contours . . . I can clearly recognize, grasp and enjoy.” 24 Fundamentally, Mendelssohn’s concept of the “musical idea” (i.e. the “theme”) can be traced back to Hegel’s idealism – the idea is the carrier of all meaning, and for that meaning to be “clear” and communicable, it has to become “concrete” in an adequate fashion. 25 Although Hegel himself never considered music to be able to communicate such concrete meaning, and never used the term “idea” in a context referring to music, Mendelssohn – like many of his contemporaries – sought in music an “ideal” art. After having become disenchanted with the potential of “extramusical” representation as attempted in the picturesque concert overtures of the late 1820s and early 1830s, the frequent selection of self-contained, song-like “musical ideas” as well as their clear presentation were steps in that direction. 26

Next to the concentrated motivic work apparent in the string quartets, the two Piano Trios opp. 49 (1839) and 66 (1845) seem more relaxed – almost exuberant in op. 49 – which no doubt contributed to their comparatively larger appeal to the public. It was in the review of the first trio that Robert Schumann called Mendelssohn “the Mozart of the nineteenth century,” and the work itself “the trio masterpiece of the present time . . . which grand- and great-grandchildren will enjoy in years to come.” 27 The techniques of motivic development and combination are of course retained, but with the added interest of the two different textures and timbres. Mendelssohn makes use of this “added layer” not only through much motivic permutation and counterpoint, but also by reintroducing the idea of a superimposed theme familiar from the earlier works. The recapitulation in the first movement of op. 49 is enriched by a new countermelody first in the violin, then in the cello. The sheer expansive beauty of the melodic writing – particularly in the first two movements – is enhanced through the typical repetition of the material with exchanges of piano and string texture, at times also between the two individual string instruments; the works gain considerable length this way besides (the first movement of op. 49 is 616 bars long!). Mendelssohn’s unpretentious but effective style of piano writing lends itself perfectly to chamber music: it is motivically, but not texturally dense, and abounds with arpeggios and other figurations that can function thematically or as accompaniment. The composer himself was very self-conscious about what he perceived to be the limit of his piano style – his “poverty of new figures for the piano”; 28 but its integration into the trio texture can be considered a success surpassing that of his solo piano music, particularly when – as often happens – a new figuration adds an entirely novel character to a familiar theme.

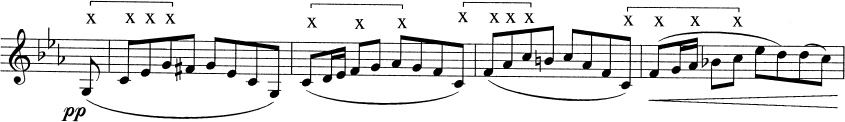

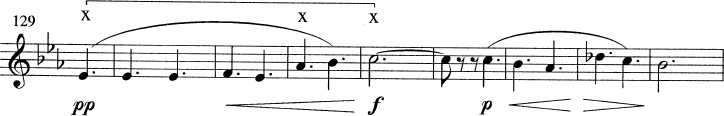

The more concentrated – and hence more typically “Mendelssohnian” – work is the less popular later composition in C minor. Here the thematic material of the entire cycle is interconnected through the common substance of the rising second-inversion chord (see Example 8.4 ). Moreover, the Finale reintroduces an element of “extra-musical” meaning: in one of the most enchanting moments in all of chamber music, the restless 6/8 motion dies down, and out of nowhere, the piano softly plays a chorale tune in chordal homophony. The composer alludes to at least two traditional hymns – “Gelobet seist du Jesu Christ” and “Herr Gott dich alle loben wir” – in addition to an organ chorale and a psalm setting of his own composition, Lord hear the voice of my complaint of 1839. 29 But he does not actually quote more than a few notes from each; without being too specific, he lends a general air of sacred celebration to the movement which culminates in a grand apotheosis of the chorale.

Example 8.4 Piano Trio op. 66 in C minor

(a) first movement, first theme

(b) first movement, second theme, mm. 23–26

(c) first movement, third theme, mm. 63–66

(d) second movement, B section, mm. 39–43

(e) finale, first theme, mm. 1–5

(f) finale, second theme, mm. 20–26

(g) finale, third (‘chorale’) theme, mm. 129–137

Whereas the octet, the string quartets and the trios are obviously at the centre of Mendelssohn’s activity as a composer, and rank among the finest specimens of their genre in the nineteenth century, neither the composer nor his audience paid as much attention to the sonata for solo instrument and piano. As mentioned above, a number of youthful compositions fall into this category, but only the Violin Sonata in F minor of 1823 had appeared in print, as op. 4 in 1824. It is in the old-fashioned three-movement format, but looks forward to the string quartets through the use of instrumental recitative in the introduction to the first movement. The violin sonata of 1838 was never considered worthy of publication. The two Cello Sonatas opp. 45 and 58 were indeed published in 1839 and 1843 respectively; they make full use of the cantabile qualities of the cello, but lack the spark that make the contemporary trios so successful. The earlier work, written for the composer’s brother Paul, even returns to the “old-fashioned” three-movement scheme. The most interesting feature of the later one is the slow (third) movement which is another experiment in instrumental chorale: this time, the chorale appears from the beginning in the piano, alternating with recitative-like passages in the cello before the two different spheres of expression are united.

When speaking of Mendelssohn’s “late works,” it is important to note that all compositions with opus numbers higher than 72 were published after the composer’s death. They do not reflect the chronology of composition; more importantly, they refer to works that Mendelssohn himself refused or failed to publish. Among the chamber works in this category, it is easy to disregard the so-called “String Quartet” op. 81, a haphazard combination of an Andante in E major, a Scherzo in A minor, a Capriccio in E minor, and a fugue in E![]() major, composed in the years 1847, 1847, 1843, and 1827 respectively. The String Quintet “op. 87” of 1845, on the other hand, was never cleared for publication, but it is a finished four-movement cycle. It continues the tradition of the mature quartets in its presentation of the thematic material in a clear manner in the top voice; the tendency toward orchestral writing becomes even more pronounced. Although contrapuntal writing and “developing variation” are by no means absent from the work, Mendelssohn’s interest often turns away from motivic development and toward sound and texture as such, with long passages dominated by a single rhythm or figuration. The first movement with its extensive use of tremolo and unison is an example of this new trend, even more so the darkly intense Adagio e lento reminiscent of the late Schubert. The limits of this style become apparent in the Finale, an almost completely monothematic sonata-rondo. The simple sixteenth-note figuration that is the theme lacks the potential to sustain a prolonged structure, and it is no surprise that this movement was the reason for the withdrawal of the work.

30

major, composed in the years 1847, 1847, 1843, and 1827 respectively. The String Quintet “op. 87” of 1845, on the other hand, was never cleared for publication, but it is a finished four-movement cycle. It continues the tradition of the mature quartets in its presentation of the thematic material in a clear manner in the top voice; the tendency toward orchestral writing becomes even more pronounced. Although contrapuntal writing and “developing variation” are by no means absent from the work, Mendelssohn’s interest often turns away from motivic development and toward sound and texture as such, with long passages dominated by a single rhythm or figuration. The first movement with its extensive use of tremolo and unison is an example of this new trend, even more so the darkly intense Adagio e lento reminiscent of the late Schubert. The limits of this style become apparent in the Finale, an almost completely monothematic sonata-rondo. The simple sixteenth-note figuration that is the theme lacks the potential to sustain a prolonged structure, and it is no surprise that this movement was the reason for the withdrawal of the work.

30

The last finished chamber work is similar to the quintet in some ways, radically different in others. During the summer of 1847, while on holiday in Switzerland, Mendelssohn wrote his F minor Quartet op. 80. Although it is hazardous to link certain works to certain biographical events, the tone of this work – which might well be described as desperate – bears an obvious relationship to the composer’s state of mind after Fanny’s sudden death on 17 May 1847. “I feel entirely void and without form, when I try to think about music”, the composer wrote on 24 May. 31 Eric Werner calls the quartet “the cry of grief . . . of the suffering creature”; 32 in any case, the new trend in chamber composition already apparent in op. 87 is put to a much more emotional use. The orchestral texture, the tremoli, the lack of self-contained melodies, the sudden harmonic shifts, the emphasis on sound and rhythm as such – all these are used to transport emotions of unprecedented negative force. Three of the four movements are in F minor; the presentation of material is reduced to scalar passages and occasional snippets of motivic development in the first movement, to unusual rhythmic gestures (see the hemiolic cross-rhythms in the first bars) in the Scherzo, to restless figurations in the finale. As Friedhelm Krummacher has shown, Mendelssohn almost certainly considered the quartet to be a “finished” composition destined for publication; the autograph displays the large number of corrections typical for Mendelssohn when revising on of his works either for performance of for publication. 33 Hence, unlike in the Quintet op. 87 (and unlike the “Italian” Symphony, for that matter), the lack of authorization was not a conscious withdrawal of a work considered unsuccessful, but a result simply of the composer’s death only a few months after completion.

Whatever its biographical implications might be, the work stands as a milestone in Mendelssohn’s creative development as a composer. It renounces all the techniques of motivic manipulation and interplay, looking forward instead to the compositions of Smetana and Hugo Wolf. All in all, however, Mendelssohn’s main legacy to nineteenth-century chamber music was in fact not the “new style” of the last works, but the integration of melodic counterpoint into chamber music, from Schumann to Brahms, Dvořák, and beyond.