Though scholarship is generally agreed about the prominent position in Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy’s oeuvre of sacred music, how to assess its role for his identity as a composer has generated contrasting lines of inquiry. We shall begin by briefly considering the dynamic of religion in the composer’s family, and then propose some ways in which the dynamic played out in his sacred choral and chorale-related works.

As the grandson of the leading Jewish philosopher of the Aufklärung , Moses Mendelssohn, Felix was of course mindful of his Judaic roots, which encouraged some scholars to search for Jewish influences in his music. As early as 1867, Camille Selden assumed that Felix had frequented a synagogue and was well versed in Hebrew; 1 two years later, Hippolyte Barbedette was able to hear in the composer’s music echoes of Jewish psalmody. 2 In 1880, Sir George Grove, whose pioneering encyclopedia article set the foundation for modern Mendelssohn research, assessed his setting of Psalm 114 op. 51 (“When Israel out of Egypt came,” 1839) thus: “The Jewish blood of Mendelssohn must surely for once have beat fiercely over this picture of the great triumph of his forefathers, and it is only the plain truth to say that in directness and force his music is a perfect match for the splendid words of the unknown Psalmist.” 3 More focused attempts to trace Jewish elements in Mendelssohn’s music ensued in the second half of the twentieth century. Jack Werner proposed in 1956 that a cadential figure comprising a descending minor triad, encountered in a variety of works ranging from the oratorio Elijah to Lieder ohne Worte and the Variations sérieuses , alluded to a blessing sung during Passover and other Festivals; Werner even speculated that Felix had visited a synagogue “in search of ‘local colour.’” 4 And in 1963, Eric Werner associated the head motive of the chorus “Behold, God the Lord passed by!” (Elijah , no. 34; I Kings 19: 11, 12) with a melody “to which the 13 Divine Attributes (Exodus 24: 6, 7) have been sung since the fifteenth century in all German synagogues on the High Holy Days.” The source, Werner assumed, “must have impressed itself upon the boy and associated itself with the representation of the Divine. Thus, through the mysterious workings of creative fantasy, this association may have been conjured from the subconscious.” 5

But the search for a Jewish character in Mendelssohn’s music is not at all unproblematic. First of all, as Jeffrey Sposato has argued, 6 there is no evidence Felix ever attended a synagogue during his youth; rather, the composer’s father, Abraham, intended early on to raise his children as Christians. Felix’s name does not appear in a Jewish register of births for Hamburg, where he was born on 3 February 1809; 7 and Carl Friedrich Zelter later even claimed to Goethe that Felix was uncircumcised. 8 On 21 March 1816, Felix and his siblings were baptized as Protestants in Berlin, and received the additional surname Bartholdy – the seven-year-old Felix Mendelssohn became Felix Jacob Ludwig Mendelssohn Bartholdy – evidently on the advice of Jacob Bartholdy (a maternal uncle of Felix who had converted eleven years before) that the family “adopt the name of Mendelssohn Bartholdy as a distinction from the other Mendelssohns.” 9 (Whether the composer’s parents noted the significance of the day – J. S. Bach’s birthday – is not known.) Six years later, in October 1822, Felix’s parents were baptized in a clandestine ceremony in Frankfurt, and from this time date the earliest surviving family letters with signatures that incorporate the name Bartholdy. When, two months later, Felix appeared in a concert of the soprano Anna Milder-Hauptmann, an anonymous critic asserted that the “boy was born and raised in our Lutheran religion,” 10 a bit of misinformation presumably disseminated by his parents. Still, though Abraham preferred that in time the family surnames would contract to M. Bartholdy and eventually Bartholdy, the composer signed his name and published his music throughout his career as Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, as if, in Rudolf Elvers’ phrase, to join the two names in a single breath. 11

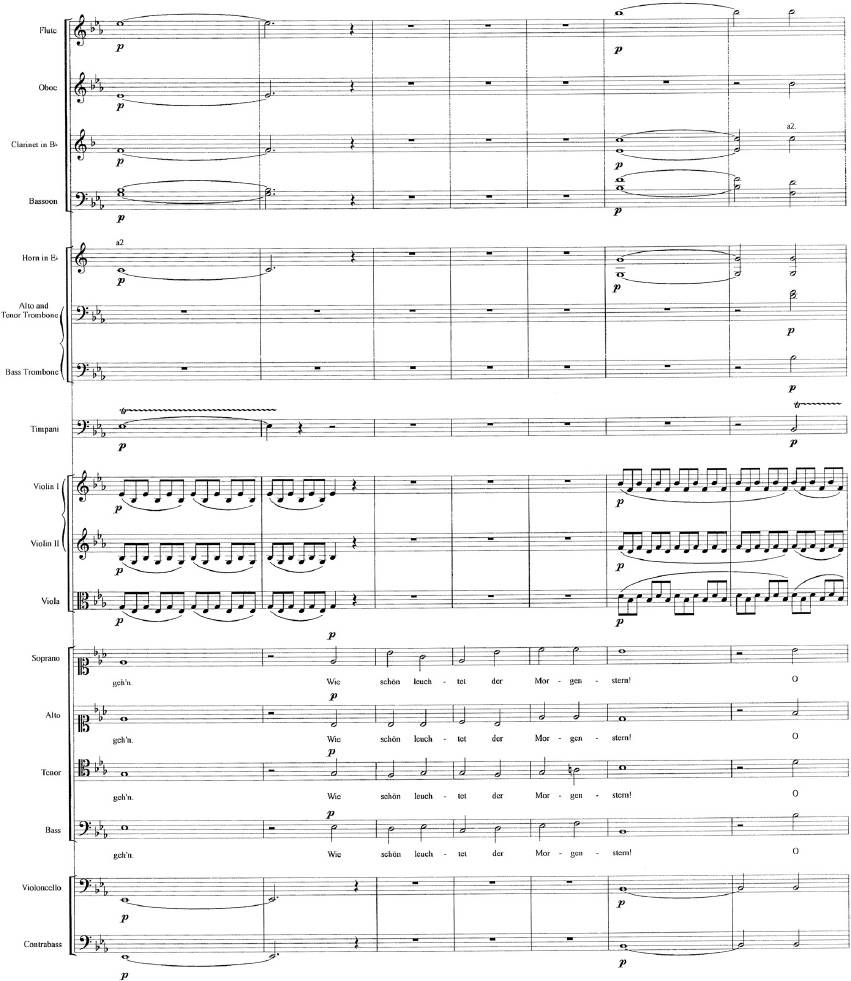

A tension between Felix’s Jewish ancestry and his Protestant upbringing might help elucidate the breadth of his sacred music, which of course draws on scriptures from the Old Testament, such as the cantata-like psalm settings and oratorio Elijah , and the New, including the oratorios St. Paul and the unfinished Christus , which also feature such staples of Protestant worship as the chorales Wachet auf and Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern . But Felix’s familial life and sense of spiritual identity were in fact more complex than might be explained by Jewish–Protestant ambivalence. Indeed, the Mendelssohns were no strangers to questions of religious tolerance, outside as well as inside the family. Though Moses Mendelssohn, who had argued in Jerusalem (1783) that Judaism, as a rational religion based upon universal truths, was not incompatible with the interests of the modern Prussian state, continued to practice his faith, four of his six surviving children did not. Two, including Abraham, became Protestants, and two, Catholics. The eldest, Brendel, managed to experience all three faiths: she married the Jewish banker Simon Veit, had an affair with the young literary critic Friedrich Schlegel, divorced Veit in 1799, converted to Protestantism, assumed the name Dorothea, married Schlegel in 1804, and embraced Catholicism with him in 1808. One generation of the Mendelssohn family thus tested the boundaries of the three principal European faiths.

As Felix Gilbert suggested perceptively in 1975, the fault lines in the family emerged not so much between the Jewish and Protestant branches – Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy maintained lifelong cordial relations with his uncle Joseph Mendelssohn, and in the 1840s assisted in advocating a new collected edition of Moses Mendelssohn’s works 12 – as between those members holding liberal versus conservative religious views. 13 Thus, Felix’s grandmother, Bella Salomon, an Orthodox Jew, responded to the apostasy of her son Jacob (Salomon) Bartholdy by cursing and disinheriting him when he accepted baptism into the Protestant faith in 1805. Similarly, when the young painter Wilhelm Hensel, son of a Protestant minister and a suitor for Fanny Mendelssohn Bartholdy’s hand, seriously considered becoming a Catholic in 1823, Fanny’s mother Lea intervened, for in her view “Catholicism always led to fanaticism and hypocrisy.” 14 And when, in 1827, Felix composed the motet Tu es Petrus on a fundamental Catholic text (Matthew 16: 18, “Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church”), Felix’s circle wondered, perhaps in jest or perhaps half seriously, whether Felix “might have turned Roman Catholic.” 15

The dynamic of contrasting religious faiths thus played itself out in the Mendelssohn family – not at all surprising, when one considers that in the eighteenth century Moses Mendelssohn himself had argued eloquently for religious tolerance. According to Joseph Mendelssohn, Moses held that “different religious views must not be suppressed among mankind, and that the world would succumb to dreadful barbarism if it were possible to make one religion the only religion.” 16 Now when we survey the corpus of Felix’s mature sacred music, we find, not surprisingly, a heavy weighting toward German Lutheran music, but also a representation of other faiths. There are, for example, several by no means insignificant Catholic settings – in addition to Tu es Petrus , the polychoral motet Hora est for sixteen voices and organ (1828), Psalm 115 op. 31 (originally set after the Vulgate version, Non nobis Domine ), Responsorium et Hymnus op. 121 (1833), Three Motets op. 39 composed for the cloistered nuns of Trinità del monte in Rome in 1830, and the unjustly neglected late setting of St. Thomas Aquinas’ sequence Lauda Sion op. 73 (1846), to cite a few. For Anglican tastes, Mendelssohn composed that favorite of Victorian parlor rooms, the anthem Hear My Prayer , on William Bartholomew’s paraphrase of Psalm 55, and also several pieces for use in Anglican services. Of these, the most prominent are his final sacred works, the sublime Evensong canticles, Magnificat and Nunc dimittis, and, for the Morning Service, the Jubilate Deo – all three were conceived with English texts and scored for chorus and organ, though published in Germany posthumously (1848) in a cappella versions as the Drei Motetten op. 69. Of considerably lesser significance is the chorale-like cantique of 1846, “Venez chanter,” though its purpose – a contribution to the hymnal of the Frankfurt Huguenot Church 17 – underscores the composer’s first-hand experience with that faith: in 1837, he had married Cécile Jeanrenaud, daughter of a Huguenot minister, an event attended by the Catholic Dorothea Schlegel.

Evidently only once during his career did Mendelssohn contemplate composing music for a Jewish service, the consecration of the new building of the Hamburg Neues Tempel in 1844. Eric Werner believed that the result was no less than a commissioned setting of Psalm 100 scored for chorus and orchestra (now lost), and eventually published for chorus alone. 18 But the full details of this project are obscured by the passage of time, and the surviving primary sources produce as many questions as answers. 19 Because this work has been neglected in the literature since Werner’s research, a brief digression is in order here.

The year 1843 marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Temple in Hamburg, when preparations were made to construct a new building, to be consecrated at Pentecost (Shavuot) in 1844. On 14 November 1843, Dr. Maimon Fränkel, Praeses of the Temple, invited Felix to compose some Psalm settings for the ceremony. “Your sublime talent,” Fränkel wrote, “is too much the common property of the entire Fatherland, and the Mendelssohn name still always too dear to every German Israelite to prevent us from yielding to the pleasant prospect of your undertaking to compose some of these pieces . . .” 20 Though Felix’s reply does not survive, it was encouraging enough to prompt Fränkel to forward on 8 January 1844 a copy of the Gesangbuch of the Tempelverein, and to propose that Felix set three Psalms deemed appropriate for the consecration, Nos. 24, 84, and 100. Fränkel recommended that Felix arrange the first two as a cantata, and employ the translation of Moses Mendelssohn (1782). Fränkel restricted the instrumental accompaniment to an organ, but noted that the choir could be expanded from its normal complement of sixteen boys to forty, to include “ladies and gentlemen of Jewish and Christian faiths.” 21 At this point, Felix evidently began to envision a more ambitious composition, and on 12 January posed the possibility of an expanded setting with orchestral accompaniment; in addition, Felix inquired if the Lutheran version of the Psalms would be acceptable. 22 On 21 January, Fränkel agreed to the stipulation of an orchestra, and added, “we also have nothing against the use of the Lutheran Psalm translations, as long as the severities and errors [Härten und Unrichtigkeiten ] of the same are avoided.” By 1 February, Felix was apparently willing to commit himself to Psalm 24; near the end of March, Fränkel was still hopeful Felix would also complete Psalms 84 and 100. But on 8 April, Felix wrote he would be unable to take on the additional psalms; 23 on 12 April, Fränkel regretted this decision, but reaffirmed his intention to provide a worthy performance of the new setting of Psalm 24, which he expected to receive no later than mid-May. Here, regrettably, the surviving correspondence ends.

To date, no score of Psalm 24 has come to light, so it is not yet possible to verify whether Mendelssohn ever completed the composition. Compounding the mystery is the survival of one other source – an a cappella setting of Psalm 100 finished by Mendelssohn on 1 January 1844, and published posthumously in 1855 in the eighth volume of Musica sacra , a compendium of sacred music for the Berlin Cathedral. The autograph, unavailable to Eric Werner but preserved today in Kraków, Poland, shows no link to the Neues Tempel; there is, for example, no evidence that Mendelssohn revised or modified the text, which transmits the Lutheran version (Jauchzet dem Herrn, alle Welt! ). Then, too, Fränkel’s letters establish that Felix declined the invitation to set Psalm 100 for the Temple; as we know, in April 1844 Fränkel was awaiting the delivery of Psalm 24. The preponderance of evidence suggests that Mendelssohn’s setting of Psalm 100 was intended for the Berlin Cathedral. Indeed, during this period the composer, newly installed by Friedrich Wilhelm IV as director of sacred music in Berlin, was engaged in composing works for the new Prussian Agende , or Protestant liturgy, introduced at the Cathedral on December 10. 24 Among them were the three a cappella Motets op. 78 (Psalms 2, 43, and 22), and the larger setting of Psalm 98 op. 91, for double chorus and orchestra. Almost certainly, Psalm 100 belonged to this repertory, and was not a commission of the Hamburg Temple. But whether Mendelssohn finished that project, and, if he did, whether he employed the Lutheran text for Psalm 24 or drew upon his grandfather’s translation – whether the commission afforded him an opportunity to reexamine his roots late in his short life – are tantalizing questions that remain unanswered.

Despite a willingness to compose sacred music for different faiths, in his personal convictions Mendelssohn adhered to the Protestant creed. By the act of conversion mandated by his parents he had become a Neuchrist , and appears to have practiced faithfully his adopted religion. Though Heinrich Heine, who converted in 1825, cynically described baptism as an “admission ticket to European culture,” and indeed questioned the motives behind Abraham’s urge to assimilate his family, 25 there is little reason to doubt the sincerity of Felix’s faith. He remained a devout Protestant, as attested by his confirmation in 1825, 26 by his statement in 1830 that he had become a follower (Anhänger ) of the Berlin theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher, 27 by Hector Berlioz’s recollections of his meetings with the composer in Rome in 1831, 28 and by Felix’s correspondence with the pastor Julius Schubring and others, which reveals an intimate knowledge of the New Testament, and, as Martin Staehelin and Jeffrey Sposato have argued, Christological readings of the Old Testament in the oratorio Elijah . 29

Felix’s faith might explain a prominent feature not only of his sacred music but his oeuvre as a whole – the prominent use of chorales. Of course, as a student of Zelter the young Felix was steeped in the didactic utility of chorales, a fundamental part of J. S. Bach’s own method of instruction, and of his pupils’, including the theorist J. P. Kirnberger. Thus in the early 1820s, under Zelter’s guidance, Felix harmonized dozens of unembellished and embellished chorales, following a course of instruction derived from Kirnberger’s Kunst des reinen Satzes , 30 and composed several chorale fugues for string quartet. No doubt, too, Felix’s abiding attraction to the music of J. S. Bach encouraged him to draw upon the repertory of familiar Protestant chorales for the foundations of several student compositions, including the organ variations on Wie groß ist des Allmächt’gen Güte (1823), and the extended series of chorale cantatas left unpublished by the composer, of which no fewer than nine bespeak a deep study of Bach: Jesus, meine Zuversicht (1824), Christe, Du Lamm Gottes (1827), Jesu, meine Freude (1828), Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten (1829), O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden (1830), Vom Himmel hoch (1831), Verleih’ uns Frieden (1831), Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott (1831), and Ach Gott vom Himmel sieh’ darein (1832). 31 It is no coincidence that Felix’s concentration on the chorale cantata fell during the period 1824–32, the very years leading up to and immediately following his historical “centenary” revival of J. S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion . Performed at the Berlin Singakademie on 11 March and 21 March (Bach’s birthday) 1829, before a capacity audience that included the Prussian court and several celebrities (Hegel, Schleiermacher, Heine, Rahel von Varnhagen, Spontini, Zelter, and possibly Paganini), the Passion triggered the modern-day Bach Revival and rescued a foundation stone of musical Protestantism from oblivion.

According to Eduard Devrient, the actor/baritone who sang the part of Christ, Felix captured the significance of the performances by observing, “And to think that it has to be an actor and a young Jew who return to the people the greatest Christian music!” 32 We cannot corroborate the veracity of Devrient’s account, but the statement, if uttered by Felix, would suggest an acute awareness of his own relationship to Bach’s masterpiece. It is well known that Felix heavily edited the Passion, and cut no fewer than ten arias, four recitatives, and six chorales. The rationale behind these excisions has attracted scholarly attention, and indeed provoked controversy. In 1993 Michael Marissen suggested that the cuts partly reflected Felix’s desire to de-emphasize anti-Semitic passages in the text. 33 But more recently, Jeffrey Sposato has argued that Felix acted “as he perceived any other Lutheran conductor would, for he must have been aware that the idea of a Mendelssohn bringing forth this greatest Christian musical work would be viewed with skepticism.” 34 Thus, the deletions removed passages he deemed textually or musically redundant, as in Felix’s treatment of the Passion chorale O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden , the melody of which recurs six times in Bach’s Passion, but only three times in Felix’s abridgement. Perhaps more telling, though, are two slight modifications Felix made to the chorale text. In the third phrase of O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden (no. 63 of the Passion) – “O Haupt sonst schön gezieret” – Felix altered the reference to Christ’s “adorned” (gezieret ) head to “crowned” (gekrönet ), and in the fifth – “jetzt aber hoch schimpfieret” – replaced the word “insulted” (schimpfieret ) with “mocked” (verhöhnet ). By so doing, Felix altered Bach’s version to conform textually to the Berlin version. 35 That is to say, Berliners encountering the colossal Passion in March 1829 – and we must remember that the work was publicly then unknown – found a chorale identical to the one they themselves would sing in Good Friday services only weeks later, on 17 April. In one small way, then, Felix seems to have bridged the gulf separating an abstract work of art that had lain dormant for a century and the common reality of Protestant congregational worship in Berlin, heavily dependent, of course, upon chorales.

With the 1836 Düsseldorf premiere of his first oratorio, St. Paul , the 27-year-old composer achieved a breakthrough, international recognition. More than any other composition, St. Paul – readily embraced throughout Germany and abroad (including England, Denmark, Holland, Poland, Russia, Switzerland, and the United States, where three performances were given in Boston, Baltimore, and New York between 1837 and 1839) – secured Mendelssohn’s emergence at the forefront of German music. Early on, the work was viewed as a synthetic effort drawing upon the exemplars of Bach’s Passions and Handel’s oratorios. For G. W. Fink, St. Paul was “so manifestly Handelian, Bachian, and Mendelssohnian that it appears as if it really exists to facilitate our contemporaries’ receptivity to the profundities of these recognized tone-heroes.” 36 More recently, Friedhelm Krummacher has summarized St. Paul as offering a “New Testament narrative as with Bach, but neither Passion nor liturgical music; complete dramatic plot as with Handel but saturated by lyrical moments; primarily Bible text without free poetry but full of text compilations and chorale citations . . .” 37 The prominent role of chorales – Mendelssohn interspersed throughout the forty-odd numbers of St. Paul five staples from the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Protestant repertory – reveals the dependence of the oratorio on the St. Matthew Passion , and Mendelssohn’s Bachian proclivities, recalling Abraham’s assertion that “every room in which Sebastian Bach is sung is transformed into a church.” 38

Though the theorist A. B. Marx argued strenuously against the use of the chorales as an anachronism (“What? Chorales in Paul’s time, and in the events that make up his life?”), Felix’s friend Karl Klingemann viewed them as “resting points” that, like a Greek chorus, drew the attention “from the individual occurrence to the general law,” and diffused “calmness through the whole.” 39 The composer carefully coordinated the chorales to reinforce the crescendo-like sense of Steigerung that animates the oratorio, as it traces the conversion of Saul of Tarsus to Paul, the missionary of early Christianity. Thus, the overture begins with the wordless intonation of the opening strains of the chorale Wachet auf (A major), subsequently redeployed in the adjoining accelerando chorale fugue that constitutes the main body of the movement. After the initial chorus, on verses from Acts 4, we hear a straightforward, homophonic presentation of the Lutheran Gloria, the chorale Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr (no. 3). 40 Then the narrator introduces the first dramatic segment of the oratorio (Nos. 4–9), culminating in the martyrdom of Stephen, and concluding with another caesura-like chorale, this time an unadorned setting of Dir, Herr, dir will ich mich ergeben . But after Saul’s epiphany on the road to Damascus, Mendelssohn resorts to a more elaborate, embellished chorale, by reintroducing Wachet auf in D major (no. 16), now presented with complete text, and with a brightly lit orchestration that, anticipating Saul’s conversion and restoration of sight, features intermittent brass fanfares.

The topic of embellished chorale returns in Part II in no. 29, to demarcate the first phase of the apostle’s missionary work, among the Jews. At the conclusion of this chorus (“Ist das nicht der zu Jerusalem”) the chorale O Jesu Christe, wahres Licht appears, sung in a straightforward chordal style but embellished by delicate arabesques in the clarinets, bassoons, and cellos. Here Felix increases the textural complexity by arranging the accompanying patterns in imitative counterpoint, thus enriching the underlying homophony of the chorale. The final stage in his chorale treatments is achieved in no. 36, where, after Paul’s and Barnabas’s proselytizing among the Gentiles, Paul introduces a verse from Psalm 115 (“Aber unser Gott ist im Himmel, er schaffet alles, was er will!”), subsequently taken up by the Gentiles. Rising from the lower register in a sequential pattern above a tonic pedal point, the movement seems calculated to recall the opening chorus of the St. Matthew Passion . Felix strengthens the allusion a few bars later, when the added second soprano part begins to intone in sustained pitches against the choral polyphony strains of the Lutheran Credo, the chorale Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott , recalling Bach’s addition of the chorale O Lamm Gottes unschuldig to the majestic polyphony of his opening chorus. Felix’s chorus sings in imitative counterpoint, so that the appearance of the chorale as an additional contrapuntal strand effectively reorients the movement toward a chorale fugue. The choice of genre here is strategic – the Paulinian assertion of justification by faith completes the series of intensified chorale treatments, ranging, as we have seen, from the text-less, partial chorale of the overture to fully texted, homophonic and embellished chorales, and the culminating treatment in five-part counterpoint. 41 No. 36 also balances the chorale fugue of the overture, where the two competing elements symbolize spiritual awakening and struggle.

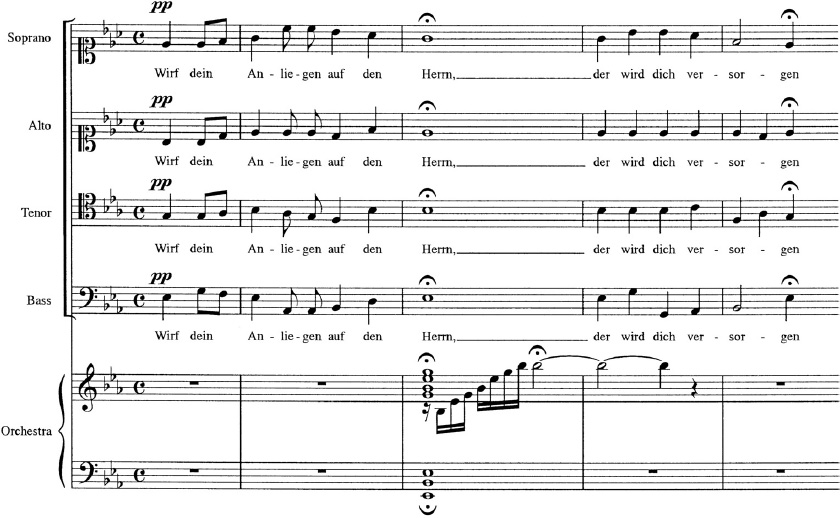

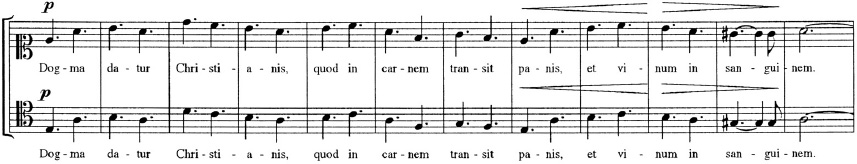

In the case of Elijah (1846), based largely on the Old Testament account in I Kings, Mendelssohn restrained considerably his reliance on chorales. Only one movement, no. 15 in Part I (“Cast thy burden upon the Lord,” for solo quartet and orchestra), offers a free-standing chorale, heard before the prophet prays for fire from heaven to answer the vain implorations of the Baalites. As Felix explained, somewhat cryptically, to his English librettist, William Bartholomew, “I wanted to have the colour of a Chorale, and I felt that I could not do without it , and yet I did not like to have a Chorale.” 42 What resulted was an adaptation of the hymn “O Gott, du frommer Gott,” from the Meiningen Gesangbuch (1693, Examples 10.1a –b ), to which Felix fitted verses from four psalms (55, 16, 108, and 25), and which he described as “the only specimen of a Lutheran Chorale in this old-testamential work.”

Though the melody would have sounded familiar to contemporary audiences, it adopted its own shape and text, and approached the status of a freely composed chorale, a middle ground that suggested the color

of a chorale, without being a

chorale. Felix took special care to tie his fabricated hymn to the role of Elijah. Thus, no. 15 appears in E![]() major, the key of Elijah’s preceding aria (no. 14, “Lord God of Abraham”), the opening phrase of which is cited pianissimo

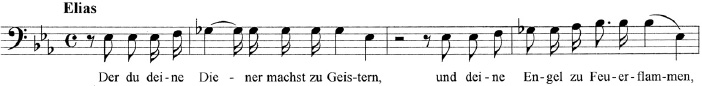

by the orchestra in the final cadence of no. 15. What is more, Elijah’s subsequent recitative (no. 16, “O Thou who makest thine angels spirits”) begins by replicating in the minor mode the initial rising third of the chorale (Example 10.2

). These musical manipulations seem to reinforce a Christological reading of Elijah as prefiguring Christ, a common nineteenth-century exegesis of the Old Testament prophet.

43

That is to say, no. 15 – to which we might add two freely composed, hymn-like passages that appear within nos. 5 (“For He, the Lord our God, He is a jealous God”) and 16 (“The Lord is God: O Israel

hear!”) – interrupts the unfolding drama, as if to interpret the Old Testament story through the lens of Christianity and to relate it to Protestant worship.

major, the key of Elijah’s preceding aria (no. 14, “Lord God of Abraham”), the opening phrase of which is cited pianissimo

by the orchestra in the final cadence of no. 15. What is more, Elijah’s subsequent recitative (no. 16, “O Thou who makest thine angels spirits”) begins by replicating in the minor mode the initial rising third of the chorale (Example 10.2

). These musical manipulations seem to reinforce a Christological reading of Elijah as prefiguring Christ, a common nineteenth-century exegesis of the Old Testament prophet.

43

That is to say, no. 15 – to which we might add two freely composed, hymn-like passages that appear within nos. 5 (“For He, the Lord our God, He is a jealous God”) and 16 (“The Lord is God: O Israel

hear!”) – interrupts the unfolding drama, as if to interpret the Old Testament story through the lens of Christianity and to relate it to Protestant worship.

(a) Elijah op. 70, no. 15

(b) “O Gott, du frommer Gott,” from the Meiningen Gesangbuch (1693)

Example 10.2 Elijah op. 70, no. 16, beginning, bass

There is, of course, another possibility – that Mendelssohn was in effect attempting to bridge the two faiths, and thus reconcile the tension between his Judaic ancestry and identity as a Christian musician by focusing on the extent, as Leon Botstein has proposed, “to which Christianity was a universalization of Judaism.”

44

The fragment of what would have been the composer’s third oratorio – titled in his posthumous catalogue of works Christus

op. 97 (1852), though probably intended for the first part of a

tripartite oratorio Felix had conceived in 1839 as Erde, Himmel und Hölle

(Earth, Heaven and Hell

)

45

– provides some intriguing evidence in the chorus “Es wird ein Stern aus Jacob aufgeh’n.” Cast in E![]() major, a prominent tonality in the first part of Elijah

, the chorus begins with shimmering string tremolos and a rising triadic figure to depict the star of Jacob (Example 10.3

). The text, from the fourth prophecy of Balaam in Numbers 24 (“There shall come a star out of Jacob, and a scepter shall rise out of Israel”), is traditionally interpreted to predict the ascendancy of King David. Now in 1834 Felix had indirectly encountered the same image when he composed the song “Sun

of the Sleepless,” to a text by Lord Byron. Nearly twenty years before, the Englishman Isaac Nathan had set Byron’s poem and incorporated it into a song anthology based upon cantorial sources, Hebrew Melodies

(1815–16). Here, Byron’s verses of an “estranged lover” became a “Hebrew melody of the long, lonely vigil, waiting for ‘the light of other days’ to shine again.”

46

Felix had borrowed a copy of Hebrew Melodies

from Charlotte Moscheles in 1833,

47

when he may well have become aware of Nathan’s reading linking the poem to Numbers 24. Felix’s setting, for which he himself provided the German translation “Schlafloser Augen Leuchte,”

48

begins and ends with a gently repeated high pitch on the fifth scale degree, capturing Byron’s couplet, “So gleams the past, the light of other days, which shines but warms not with its powerless rays” (Example 10.4

).

major, a prominent tonality in the first part of Elijah

, the chorus begins with shimmering string tremolos and a rising triadic figure to depict the star of Jacob (Example 10.3

). The text, from the fourth prophecy of Balaam in Numbers 24 (“There shall come a star out of Jacob, and a scepter shall rise out of Israel”), is traditionally interpreted to predict the ascendancy of King David. Now in 1834 Felix had indirectly encountered the same image when he composed the song “Sun

of the Sleepless,” to a text by Lord Byron. Nearly twenty years before, the Englishman Isaac Nathan had set Byron’s poem and incorporated it into a song anthology based upon cantorial sources, Hebrew Melodies

(1815–16). Here, Byron’s verses of an “estranged lover” became a “Hebrew melody of the long, lonely vigil, waiting for ‘the light of other days’ to shine again.”

46

Felix had borrowed a copy of Hebrew Melodies

from Charlotte Moscheles in 1833,

47

when he may well have become aware of Nathan’s reading linking the poem to Numbers 24. Felix’s setting, for which he himself provided the German translation “Schlafloser Augen Leuchte,”

48

begins and ends with a gently repeated high pitch on the fifth scale degree, capturing Byron’s couplet, “So gleams the past, the light of other days, which shines but warms not with its powerless rays” (Example 10.4

).

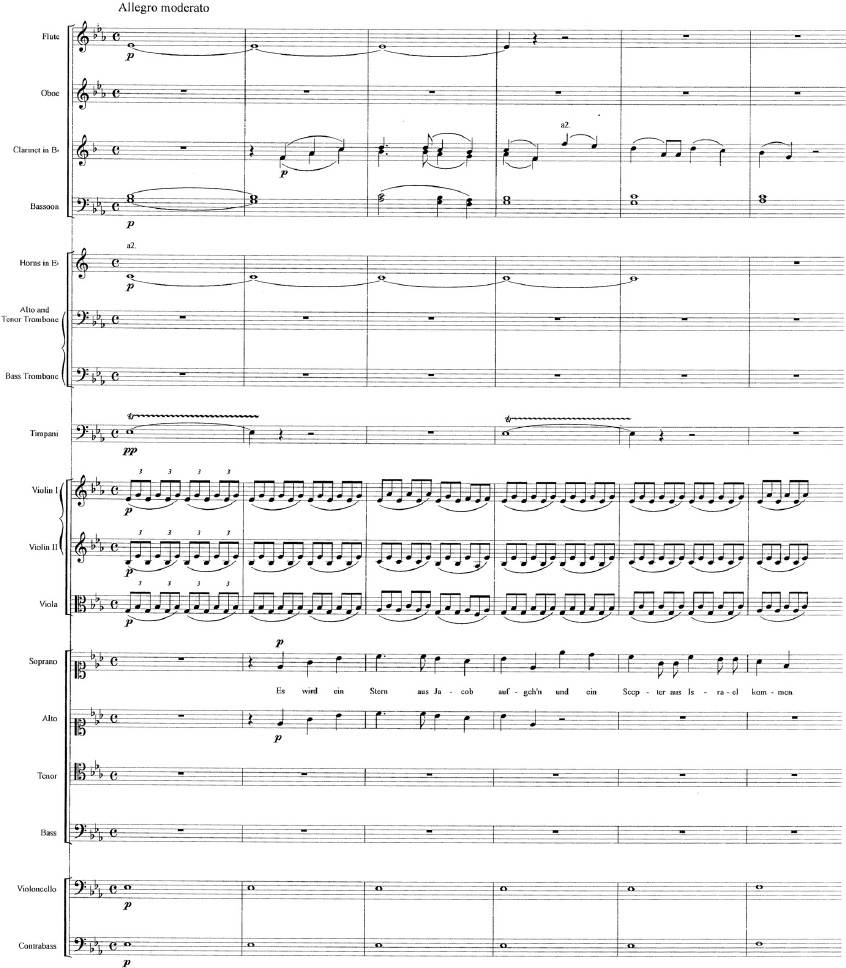

Example 10.3 Christus [op. 97], excerpt

Example 10.4 “Schlafloser Augen Leuchte” (Byron), beginning

In Christus , Felix’s setting of Numbers 24 ends with a radiant chord, again exposing the fifth scale degree in the soprano register, though now supported with a complete triad, in contrast to the hollow fifths of “Sun of the Sleepless.” But more telling is the final portion of the chorus, in which Felix elides the verses from Numbers with a setting of the familiar chorale Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern , and thus links the Star of David to the Star of Bethlehem (Example 10.5 ).

Example 10.5 Christus [op. 97], excerpt

The chorale preserves the E![]() major tonic and also reveals a close motivic relationship to the head motive of the chorus; both describe forms of the

tonic triad supported by C, neighbor note to the fifth degree, and are musically compatible. Mendelssohn’s Christological reading of the Old Testament text seems clear enough, but the music also possibly expresses a symbolic intent to bridge the Old and New Covenants. In this case, the chorale is the agent of that inter-faith connection.

major tonic and also reveals a close motivic relationship to the head motive of the chorus; both describe forms of the

tonic triad supported by C, neighbor note to the fifth degree, and are musically compatible. Mendelssohn’s Christological reading of the Old Testament text seems clear enough, but the music also possibly expresses a symbolic intent to bridge the Old and New Covenants. In this case, the chorale is the agent of that inter-faith connection.

Be that as it may, to contemporary nineteenth-century audiences, the introduction of popular chorales in Felix’s music – to the examples adduced we might add the insertion of Ein’ feste Burg into the finale of the “Reformation” Symphony (1830), and of several chorales in the Organ Sonatas Op. 65 (1845), not to mention the striking appearance of Vom Himmel hoch in Athalie (1845) 49 – would have imparted a seemingly clear meaning: like an avowal of faith, they would have symbolized to the general public Felix’s musical Protestantism.

Equally significant in this regard is the persistence with which he employed chorales in a variety of genres – vocal and instrumental, with and without clear ties to liturgical function – and, furthermore, his willingness to create freely composed chorales of his own. These “imaginary,” textless chorales, which Mendelssohn insinuated into several instrumental works, including the piano Prelude and Fugue in E minor op. 35 no. 1 (1827), slow movement of the Cello Sonata in D major op. 58 (1843), and finale of the Second Piano Trio op. 66 (1845), form a special group. 50 What was his motivation in these experiments? Injecting an element of spirituality into the concert hall, the pseudo-chorales entice the listener with skillfully designed melodies that have a ring of familiarity and seem to connote collective, congregational worship. Thus the culminating chorale of the Fugue op. 35 no. 1, which Charles Rosen has viewed as a masterpiece but also as the “invention of religious kitsch,” 51 approaches in one of its strains almost note for note a phrase from Ein’ feste Burg (Example 10.6 ). Mendelssohn wrote this fugue in 1827 after the death of his friend August Hanstein; the highly dissonant fugue, on a subject rent by tritones, depicted the course of Hanstein’s disease; the culminating chorale at the end, in the major mode and distinguished by smooth, stepwise motion, his release through death and spiritual redemption. 52 The unabashedly religious character of the piece thus bore a personal significance for Mendelssohn. We do not know if similar autobiographical elements inform the free chorales in the Second Cello Sonata and Piano Trio, but almost certainly the motivation was the same – to inject spiritual elements into the music, so that works intended for the concert hall began to encroach upon the domain of sacred music for the church.

Example 10.6 Fugue in E minor op. 35 no. 1, mm. 116–24, melody

The symphony-cantata “Lobgesang” op. 52 (1840), and the events attending its Leipzig premiere in the Thomaskirche, document in especially compelling fashion this tendency in Mendelssohn’s oeuvre. Now generally the least esteemed of Mendelssohn’s five mature symphonies – it was severely criticized by his erstwhile friend, A. B. Marx, and others for an “excessive” reliance on Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony – the “Lobgesang” raises afresh the question of what Carl Dahlhaus, in discussing St. Paul , framed as “imaginary church music.” 53 The context in which the symphony was first heard reveals the length to which Mendelssohn endeavored to break down the traditional divisions separating church and concert music. In June 1840 Leipzig commemorated the quadricentennial of Gutenberg’s invention of movable type. As the center of the German book trade, Leipzig had long been associated with publishing, and the anniversary was thus an occasion to celebrate the centuries-old trade and its guilds. 54 But the festival honored more than printing: it championed the Gutenberg Bible as the lamp that had disseminated spiritual enlightenment in German realms. And, Gutenberg’s technological advance was linked to Luther and the spread of the Reformation; as it happened, the second day of the festival, 25 June, coincided with the commemoration of the Augsburg Confession, one of the signal events in the Lutheran calendar.

On 24 June 1840, the Leipzig Marktplatz became the site of several ceremonies, including a church service, dedication of a new statue of Gutenberg, and speech by the publisher Raimund Härtel, who likened the inventor to the John the Baptist of the Reformation. For this occasion Mendelssohn composed a Festgesang for male chorus and double brass band, spatially separated so as to generate echo effects in the square. The text, by an obscure Gymnasium teacher, Adolf Prölz, summarized in some insipid verses the principal metaphors of the festival – Gutenberg as a German hero who had lit a symbolic torch, and the victory of light over darkness through the dissemination of printing. To underscore the quasi-sacred function of his music, Mendelssohn framed the work with two staples of Lutheran worship, the chorales Sei Lob und Ehr der höchsten Gut and Nun danket alle Gott , to which he fitted Prölz’s verses. Today these two settings are forgotten, but one of the internal movements, a part-song that celebrated Gutenberg as a German patriot, enjoyed a curious afterlife never imagined by Mendelssohn: in 1856 the organist William H. Cummings set the words of Charles Wesley’s Christmas hymn, “Hark! The herald angels sing,” to the melody. By 1861, the new contrafactum had appeared in a hymnal, and begun its second life as a Christmas carol.

On the second day of the Gutenberg festival, 25 June 1840, Mendelssohn premiered in the Thomaskirche his “Lobgesang,” a hybrid concatenation linking three symphonic movements to a cantata of nine movements. Mendelssohn himself chose the texts from the Bible, chiefly from the Psalms, and calculated to underscore in a general hymn of praise the triumph of light over darkness, of spiritual awareness over ignorance. In many ways, the textless symphony impresses as an instrumental composition aspiring toward imaginary church music, while the cantata, with the addition of sacred texts, in turn approaches the condition of liturgical music.

Thus the symphony begins by imitating responsorial psalmody – the trombones announce a formulaic intonation answered by the orchestra, establishing an alternating pattern between the two (Example 10.7 , recognizable in the intonation is the psalm formula Mozart used in the finale of his “Jupiter” Symphony, and Mendelssohn applied in a variety of works). 55

Example 10.7 Lobgesang op. 52, mvt. 1, mm. 1–2, trombones

But the meaning of this abstract psalmody is unclear – there are of course no words, and the introduction gives way, with a bit of a jolt, to a fully orchestral movement in sonata form, resonant with echoes of the recent symphonic tradition of Beethoven and Schubert (in 1839 Mendelssohn had premiered the latter’s “Great” Symphony, D. 944). Now in the second movement, a lilting scherzo in G minor, comes another allusion to an imaginary sacred melody: in the Trio Mendelssohn introduces a freely composed chorale – this one in G major, with phrases that sound at once familiar and unfamiliar. But again we can only imagine the text of this voiceless chorale. The answer comes with the introduction of texts in the cantata. First the chorus adds to the trombone intonation the closing verse of Psalm 150 – “Let everything that breathes praise the Lord.” And a few movements later, after we have experienced the turn from darkness to light, we encounter the chorale Nun danket alle Gott , first a cappella , and thus divorced from the symphonic context, and then with orchestral accompaniment. The chorale appears in G major, reviving the key of the textless chorale in the scherzo. What is more, Nun danket alle Gott is the chorale previously used in the Festgesang , and thus a direct link between the symphony-cantata and the public ceremonies celebrating the Gutenberg anniversary.

The “Lobgesang” marked Mendelssohn’s most ambitious attempt to dissolve the barriers between concert music and functional church music. In the last years of his life, he attempted a somewhat similar experiment, but from the different perspective of writing music for actual liturgical use. The venue now shifted from the Leipzig Gewandhaus and Thomaskirche to the Protestant Cathedral of Berlin, where in 1842 Friedrich Wilhelm IV named Mendelssohn Generalmusikdirektor in charge of sacred music. A new male choir was trained and established at the cathedral, and the king oversaw a reform of the Prussian liturgy; among the changes was the institution of an Introit psalm and verse before the Alleluia , both sung by the choir, and the sharing of responses throughout the service by the choir and congregation. 56 The revised liturgy was introduced during Advent, on 10 December 1843; then, for the Christmas service, new music by Mendelssohn was performed, including a setting of Psalm 2 for chorus and organ (op. 78 no. 1), 57 and an a cappella verse, “Frohlocket ihr Völker” (op. 79 no. 1). But what the cathedral clergy had not anticipated was Mendelssohn’s decision to replace the Gloria patri after the Psalm with the chorus “For unto us a Child is born” from Handel’s Messiah , for which he hastily prepared an organ accompaniment. 58 And for the service on New Year’s Day 1844, Mendelssohn went considerably further. His newly composed Introit psalm, Psalm 98 (op. 91), began, appropriately enough, with an a cappella double choir, introduced by an intonation in the bass that strikingly recalls the opening of the “Lobgesang” (Example 10.8 ). But for the fourth, fifth, and sixth verses – the command to make a joyful noise to the Lord with all manner of instruments – Mendelssohn introduced a harp, trombones, and trumpets, the thin end of an instrumental wedge that eventually materialized fully in the seventh verse as a full orchestra for “Let the sea roar, and all that fills it.” The closing verse, “He will judge the world with righteousness and the peoples with equity,” unfolded as a Handelian celebratory chorus. And the key of the conclusion, D major, facilitated the final surprise – the use of the “Hallelujah” chorus from Messiah in lieu of the Gloria patri. The effect of the whole was thus to begin in a pure a cappella style but then to introduce instrumental forces, a crescendo effect that gradually impelled a piece of liturgical music to approach the condition of concert music.

Example 10.8 Psalm 98 op. 91, beginning

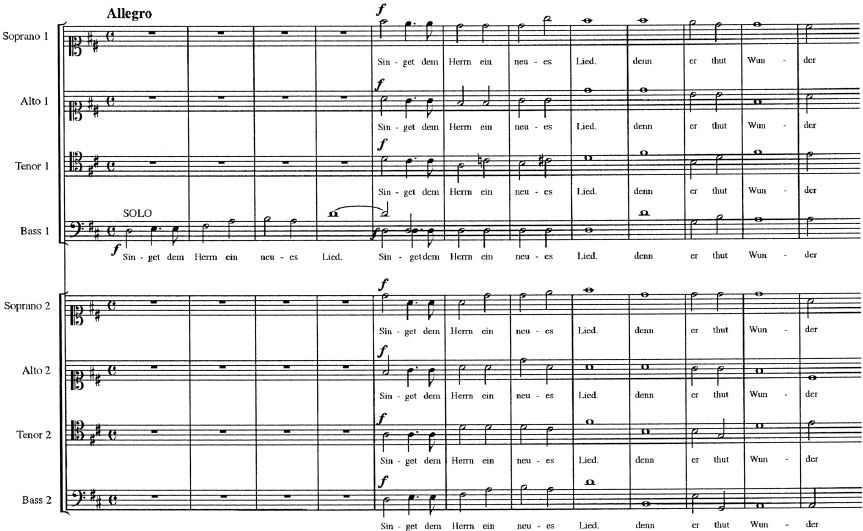

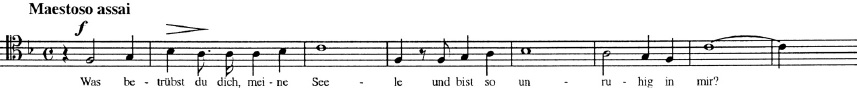

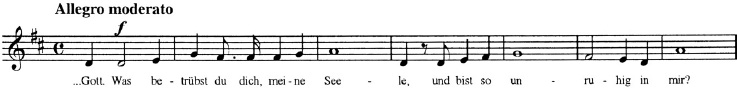

Mendelssohn composed music for two more services in 1844, Passion Sunday and Good Friday, for which he contributed the two introit psalms, nos. 43 and 22 (op. 78 nos. 2 and 3), now joined to compact settings of the lesser doxology, “Ehre sei dem Vater.” Conspicuously, all of this music is a cappella , probably in response to controversy between Mendelssohn and the cathedral clergy about the role of instruments, with Mendelssohn seeking to increase their scope, and the clergy to limit it. But in the case of Psalm 43, Mendelssohn seized the opportunity to find a new bridge between liturgical and concert music. Noticing that Psalm 43 cites verses from Psalm 42 – notably “Why are you cast down, O my soul, and why are you disquieted within me? Hope in God, for I shall again praise him, my help and my God” – he could not avoid reusing music from his cantata-like setting of Psalm 42 op. 42, for chorus and orchestra (1838), a work composed as concert music and premiered in the Gewandhaus (Examples 10.9 and 10.10 ). In the end, self-quotation thus became a way of uniting imaginary and functional church music.

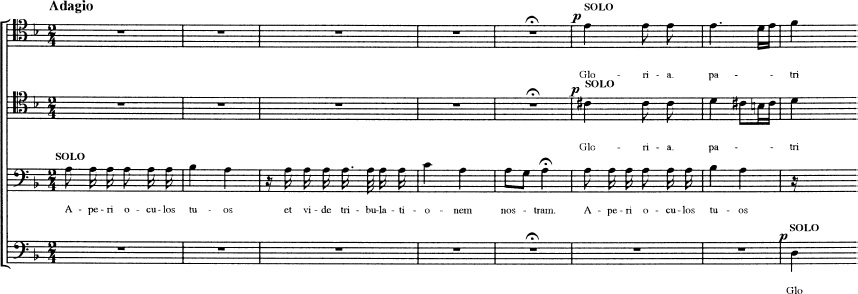

Example 10.10 Psalm 43 op. 78, no. 2

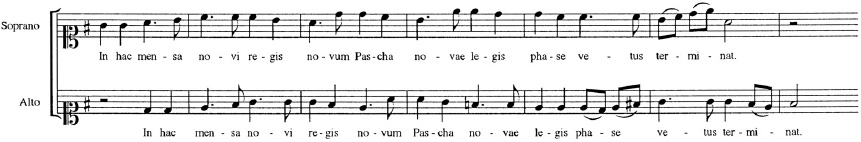

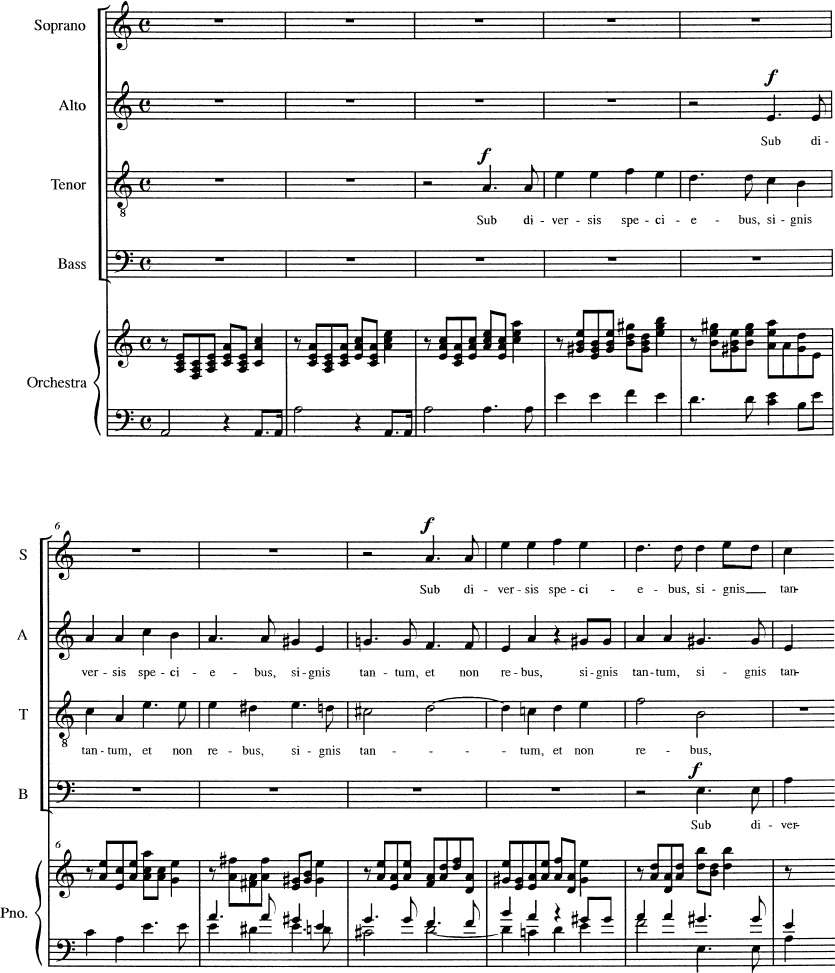

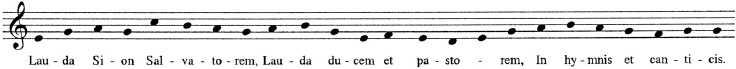

The divide between concert music and music for worship informs also Mendelssohn’s Catholic settings, and the principal work conceived during the Italian sojourn of 1830–31, the “Italian” Symphony op. 90. Though Eric Werner proposed that the plaintive opening theme of its slow movement was an in memoriam to Zelter, 59 there can be little doubt that Mendelssohn had in mind a sacred procession of responsorial psalmody reminiscent of his experiences in Rome. Thus the Andante begins with a formulaic intonation that hovers around the fifth scale degree. Against a walking bass, the winds then present a modal melody (with lowered seventh degree), answered by the violins, which establishes the pattern of responsorial chanting. The effect is compellingly close to a passage from Mendelssohn’s little-known Vespers setting for the twenty-first Sunday after Trinity, the Responsorium et Hymnus op. 121, composed in 1833 but left for posthumous publication in 1873 (Example 10.11 ). Here again we encounter an initial intonation centered on the fifth scale degree, answered in this case by a male choir in harmony. 60 If the Andante of the “Italian” Symphony transcended generic limitations by alluding to responsorial plainchant, in the case of the Lauda Sion op. 73, Mendelssohn composed a substantial work specifically intended for liturgical use. Indeed, when, in 1847, the English choral director John Hullah proposed a performance in London, the composer maintained “it would hardly do to use it without the Catholic Church and its ritual.” 61 Commissioned for the six-hundredth anniversary of the Feast of Corpus Christi, the composition was premiered at the Church of St. Martin in Liège on 11 June 1846. Mendelssohn decided to set the complete Latin text of Thomas Aquinas’ famous sequence, at the core of which is the doctrine of transubstantiation, the belief that during Communion the eucharistic elements are transformed into the body and blood of Christ. To convey something of the ineffable mystery of the doctrine, Mendelssohn resorted to two stratagems in the three central movements of his composition (nos. 4, 5, and 6). First, he allied the transformation of the consecrated Host, the “dogma” handed down to Christians (“dogma datur christianis”), with applications of solemn, ritualistic counterpoint – canons in no. 4, and a fugue in no. 6 (Example 10.12 a –b ). Concerning the latter, on the text “Sub diversis speciebus, signis tantum, et non rebus, latent res eximiae” (“Beneath different types, only in signs, not in real things, do the exceptional realities reside”), Mendelssohn originally had some ambivalence, as he explained to the Belgian musician H.-G.-M.-J.-P. Magis: “I had withdrawn this piece because the words already occur in the preceding section and I was afraid that it could be too long. After a renewed reading of the score with a clear head, I would like again to include this piece in the place where it belongs, although it is a bit strict and although it is a fugue and although it is too long.” 62 But despite his decision to retain the movement, the first edition of the score, published posthumously by Schott in 1849, omitted it, and thus concealed its significant role in underscoring the association of high counterpoint with one of the central dogmas of the Church. 63

Example 10.11 Responsorium et Hymnus [op. 121]

Example 10.12 Lauda Sion op. 73

(a) no. 4

(b) no. 6

Mendelssohn reserved a second stratagem for the culminating fifth movement (“Docti sacris institutis, panem, vinum in salutis consecramus hostiam”). 64 Here he unveiled the opening strains of the centuries-old sequence melody as a foreboding cantus firmus, sung three times by the choir in unison, and then once in harmony, with the cantus inverted to the bass. Mendelssohn’s source for the chant is not known. In any event, he employed not the original mixolydian setting, with its distinctive closing cadence by whole step, from the subfinalis F to finalis G, but rather a modified version to make the melody compatible with an aeolian setting centered on A (Example 10.13 a –b ).

(a) Sequence, “Lauda Sion”

(b) Mendelssohn, Lauda Sion op. 73, no. 5

Furthermore, by raising the seventh degree at the cadences to a G![]() , Mendelssohn adapted the modal melody to meet the “modern” tonal requirements of a movement in A minor. The “different” modal/tonal “types” of musical organization were thus allied with the text “sub diversis speciebus,” and its message explored further in the subsequent fugue. Here, against the four-part counterpoint, the sequence melody appeared one final time in prolonged values in the trombones and trumpets, transforming that movement into another example of a chorale fugue, now centered not on a familiar Protestant hymn, but on a Catholic sequence.

, Mendelssohn adapted the modal melody to meet the “modern” tonal requirements of a movement in A minor. The “different” modal/tonal “types” of musical organization were thus allied with the text “sub diversis speciebus,” and its message explored further in the subsequent fugue. Here, against the four-part counterpoint, the sequence melody appeared one final time in prolonged values in the trombones and trumpets, transforming that movement into another example of a chorale fugue, now centered not on a familiar Protestant hymn, but on a Catholic sequence.

According to Henry Fothergill Chorley, the Belgian premiere of Lauda Sion , attended by Mendelssohn, fell considerably short of his expectations. An under-rehearsed, “scrannel orchestra” and singers “who evidenced their nationality by resolutely holding back every movement,” struggled to make their way through the score, among an impressive gathering that including archbishops and bishops, “magnificently vested in scarlet, and purple, and gold, and damask – a group never to be forgotten.” 65 But in the final alla breve of the last movement (“Ecce panis angelorum,” “Behold the bread of the angels”), as the Host was elevated, came a “surprise of a different quality.” As the gilt tabernacle turned slowly above the altar, and as incense was swung from censers, “the evening sun, breaking in with a sudden brightness, gave a faery-like effect to curling fumes as they rose; while a very musical bell, that timed the movement twice in a bar, added its charm to the rite.” Mendelssohn reportedly whispered to Chorley, “Listen! How pretty that is! It makes me amends for all their bad playing and singing, – and I shall hear the rest better some other time.” 66 He never did; within a few weeks, he would turn his attention to final preparations for the Birmingham premiere of Elijah , in August 1846, and then consume much of his final year in revising the oratorio. Though Lauda Sion was thus consigned to posthumous publication, it did afford Mendelssohn an opportunity to explore an alternate model of sacred music, based upon the auctoritas of the chant and its modal incarnation, supported by the rich traditions of ritualistic counterpoint. Here the composer, grandson of Moses Mendelssohn and a Neuchrist , momentarily left the collective congregational space of Protestant chorales to ally himself, symbolically, with the priests, those “learned in the sacred institutions.” One has the impression that in Lauda Sion , as in Mendelssohn’s other sacred music, and indeed a fair amount of his music for the concert hall, he explored in manifold ways the elusive boundaries of real and imaginary sacred music. Perhaps this dynamic of Mendelssohn’s creative muse will yet be recognized.