CHAPTER

1

HEALTH AND HEALTH POLICY

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

- define health and describe health determinants;

- define public policy and health policy;

- begin to appreciate the important historical roles of Medicare and Medicaid;

- begin to appreciate the significance of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA);

- identify some of the important challenges for health policy;

- understand and distinguish between the two fundamental forms of health policies, allocative and regulatory; and

- understand the impact of health policy on health determinants and health.

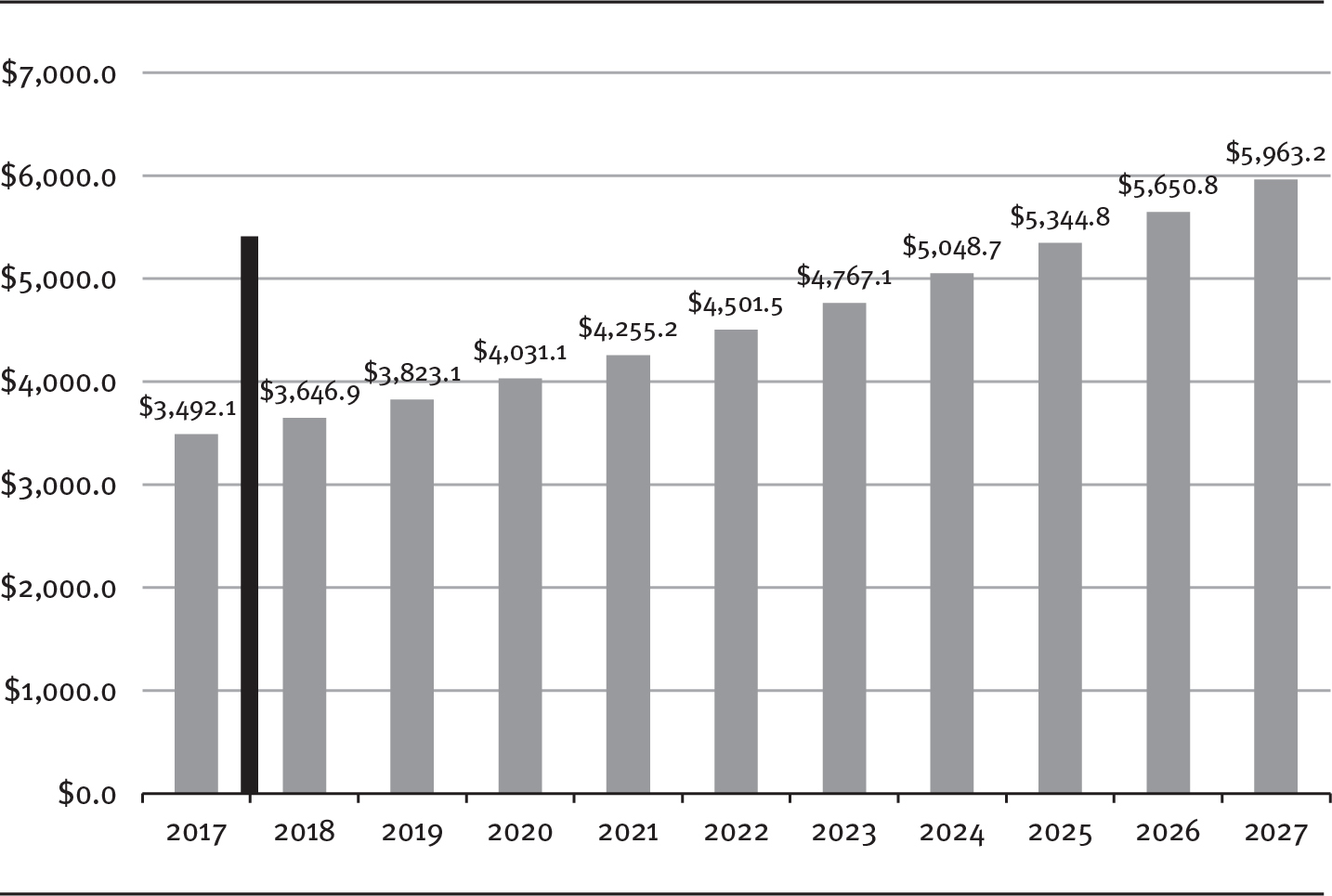

Health and its pursuit have long been woven tightly into the social and economic fabric of nations. Health is essential not only to the physical and mental well-being of people but also to nations’ economies. The United States spent about $3.5 trillion in pursuit of health in 2017, representing about 17.9 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) and equaling about $10,739 per person (CMS 2020a). This aggregate spending for healthcare and health services is referred to as National Health Expenditures (NHE). Exhibit 1.1 provides a projection of NHE.

EXHIBIT 1.1 Actual NHE, 2017, and Projected NHE, 2018–2027 (in billions)

Long Description

The x-axis shows years from 2017 to 2027. The y-axis shows NHE in billion dollars from 0.00 to 7000.00 in increments of 1000.00. A solid line is marked in between 2017 and 2018. The details of the graph are as follows:

- 2017: 3,492.1 billion dollars.

- 2018: 3,646.9 billion dollars.

- 2019: 3,823.1 billion dollars.

- 2020: 4,031.1 billion dollars.

- 2021: 4,255.2 billion dollars.

- 2022: 4,501.5 billion dollars.

- 2023: 4,767.1 billion dollars.

- 2024: 5,048.7 billion dollars.

- 2025: 5,344.8 billion dollars.

- 2026: 5,650.8 billion dollars.

- 2027: 5,963.2 billion dollars.

Source: Adapted from CMS (2020b).

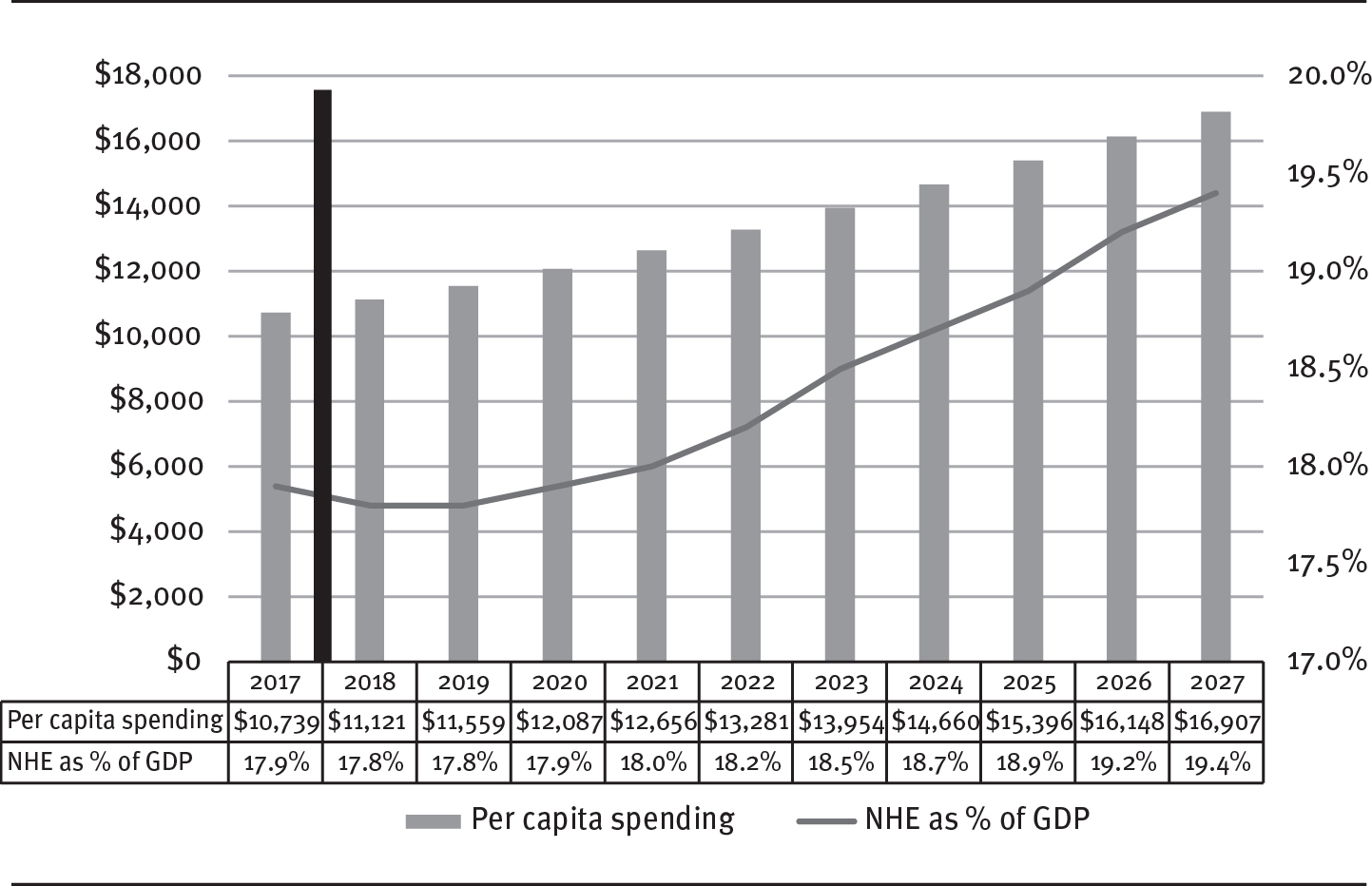

Because policymakers, particularly elected officials, often view this type of large abstract concept on an individual level, exhibit 1.2 brings the point a bit closer to home, as it displays the projected US healthcare expenditures per capita. Note the magnitude of the projected increase: approximately 60 percent over 10 years. Exhibit 1.2 also demonstrates NHE’s continued growth as a percent of GDP. Over time, the growth rate in the cost of healthcare continues to exceed the growth rate in the national economy.

EXHIBIT 1.2 Actual (2017) and Projected (2018–2027) NHE per Capita and as Percentage of GDP for 2017

Long Description

The x-axis shows years from 2017 to 2027. The y-axis on the left shows NHE in dollars from 0 to 18,000 in increments of 2,000. The y-axis on the right shows percentage from 17.0 to 20.0 in increments of 0.5 percent. A solid line is marked in between 2017 and 2018. The details of the bar graph for per capita spending and line graph for NHE as percentage of GDP are as follows:

- 2017: 10,739 dollars; 17.9 percent.

- 2018: 11,121 dollars; 17.8 percent.

- 2019: 11,559 dollars; 17.8 percent.

- 2020: 12,087 dollars; 17.9 percent.

- 2021: 12,656 dollars; 18.0 percent.

- 2022: 13,281 dollars; 18.2 percent.

- 2023: 13,954 dollars; 18.5 percent.

- 2024: 14,660 dollars; 18.7 percent.

- 2025: 15,396 dollars; 18.9 percent.

- 2026: 16,148 dollars; 19.2 percent.

- 2027: 16,907 dollars; 19.4 percent.

Source: Adapted from CMS (2020a).

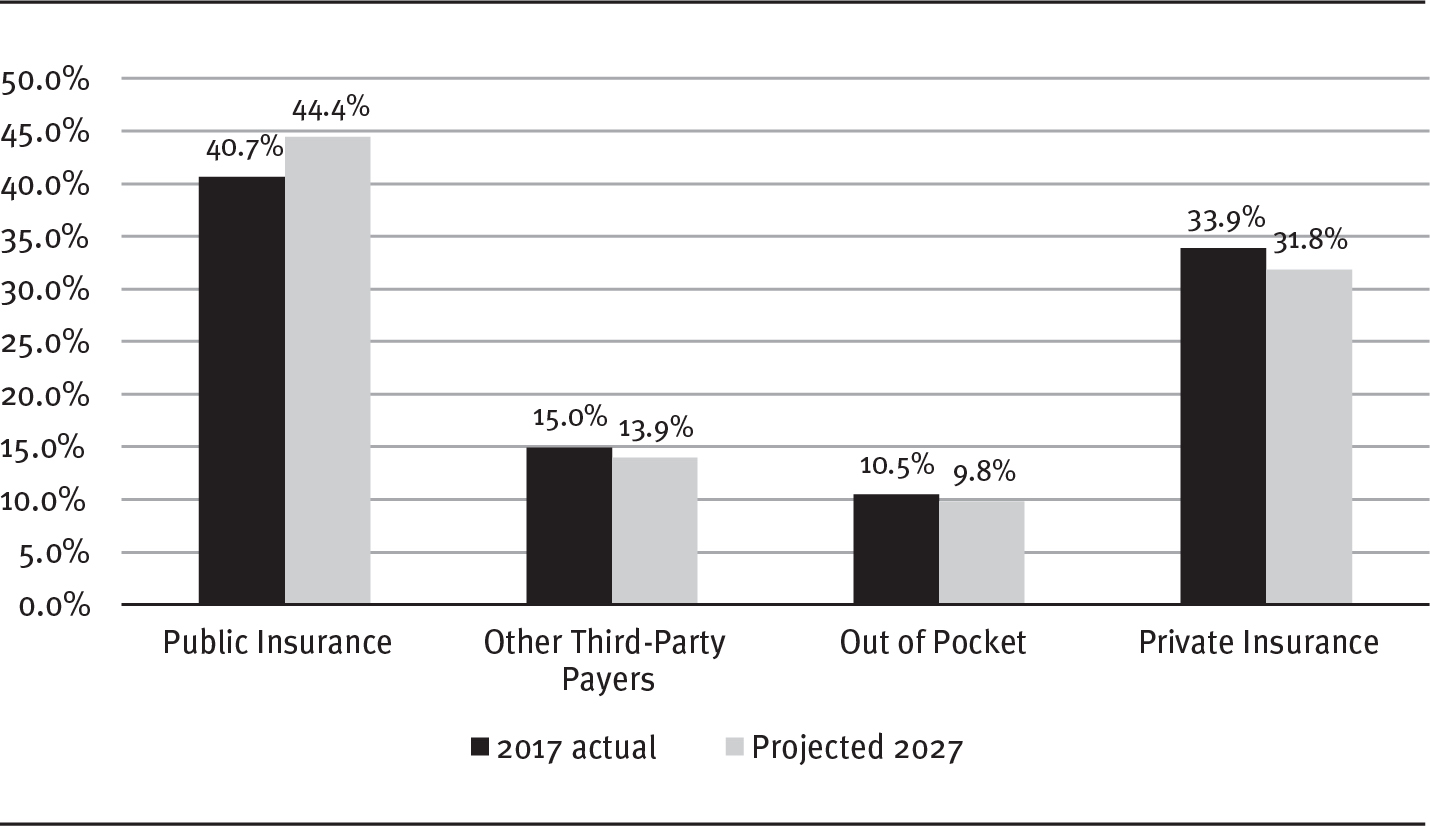

Exhibit 1.3 provides an important comparison regarding the source of the money that pays for healthcare costs. The public insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense) portion continues to grow and will pay for an increasing share of the total NHE. This growth is primarily attributable to the increase in Medicare expenditures, because of the growing percentage of elderly in the population and their greater use of healthcare resources, and Medicaid, because of the expansion funded in part by the Affordable Care Act. Thus, it is not surprising that governments at all levels are keenly interested in health and how it is pursued. As will be discussed throughout this book, government’s interest is expressed largely through public policy.

EXHIBIT 1.3 NHE by Source: Actual 2017 and Projected 2027

Long Description

The x-axis shows sources and the y-axis shows percentage from 0.0 to 50.0 in increments of 5.0. The details of 2017 actual and projected 2027 respectively are as follows:

- Public insurance: 40.7 percent; 44.4 percent.

- Other third-party payers: 15.0 percent; 13.9 percent.

- Out of pocket: 10.5 percent; 9.8 percent.

- Private insurance: 33.9 percent; 31.8 percent.

Source: Adapted from CMS (2020b).

The projections forecast that, in less than a decade, absent a significant event to change the course of events, nearly one-half of NHE will most likely come from public sources. The proportion of NHE provided by private insurance will decline slightly, as will out-of-pocket expenditures and funding from other third-party payers. (This category includes things such as workplace clinics, workers’ compensation, vocational rehabilitation, and others, some of which are also publicly sourced [Sisko et al. 2019]).

Despite government’s substantive role through health policy, most of the necessary clinical, diagnostic, and ancillary resources used in the pursuit of health in the United States are owned and controlled by the private sector. This unique public–private connection means that when government is involved in the pursuit of health for its citizens, it often seeks broader access to health services—for classes of people (Medicare: elderly and disabled people; Medicaid: the indigent) or to obtain broader access for everyone to address specific disease states (polio and flu vaccines)—that are provided predominantly through the private sector. While the private sector owns or controls the majority of the resources, government’s role has expanded over time (as examined in detail in chapter 4).

The long-established Medicare and Medicaid programs provide clear examples of this public–private approach, which is continued in the more recent expansion of insurance coverage in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111-148) of 2010. The ACA, as it is known, continues the pattern of using public dollars to purchase services in the private sector for beneficiaries, as is done under Medicare and Medicaid. These policies are critically important to understanding health policy and its effect on health in the United States. Appendix 1.1 provides an overview of the ACA, and appendix 1.2 offers similar summaries of the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

This book explores the intricate public policymaking process through which government influences the pursuit of health in the United States. The primary focus is on policymaking at the federal level, although much of the information also applies to state and local levels of government. This chapter discusses the basic definitions of health, health determinants, and health policy and their relationships to one another. Chapter 2 describes the context in which policymaking takes place. Chapter 3 discusses the dynamic nature of federalism and its impact on health policy, underscoring the different responsibilities between the federal and state governments. Chapter 4 presents a model of the public policymaking process and specifically applies this model to health policymaking. Building on the foundational material presented in the first four chapters, subsequent chapters cover in more detail the various interconnected components of the policymaking process. Chapter 10 concludes the book with attention to how health professionals, whether managers or clinicians, can build a more comprehensive and integrated, therefore more useful, level of policy competence. In this book, policy competence simply means that health professionals understand the policymaking process sufficiently to exert some influence and achieve their goals—improved healthcare services delivery. The path toward policy competence begins with some key definitions—of health, health determinants, public policy, and health policy.

Health Defined

A careful definition of health is important because it gives purpose to any consideration of health policy. Being precise about what causes or determines health is similarly important. As will be discussed more fully later, policy affects health through its impact on the determinants of health.

The World Health Organization (WHO; www.who.int) defines health as the “state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,” a definition first appearing in the organization’s constitution in 1946 and continuing unchanged through today (WHO 1946). Other definitions have embellished the original, including one that says health is “a dynamic state of well-being characterized by a physical and mental potential, which satisfies the demands of life commensurate with age, culture, and personal responsibility” (Bircher 2005). Another variation on the definition views health as a “state in which the biological and clinical indicators of organ function are maximized and in which physical, mental, and role functioning in everyday life are also maximized” (Brook and McGlynn 1991). Yet another definition adds the concept of health as a human right by saying health is “a condition of well-being, free of disease or infirmity, and a basic and universal human right” (Saracci 1997). The former European commissioner for health and consumer protection provides a definition with an important expansion by considering good health as “a state of physical and mental well-being necessary to live a meaningful, pleasant, and productive life” and further noting that “good health is also an integral part of thriving modern societies, a cornerstone of well performing economies, and a shared principle of . . . democracies” (Byrne 2004).

The WHO definition, especially as embellished with considerations of health as a right and a key principle of most democracies, not only permits consideration of the well-being of individuals and the health of the larger communities and societies they form, but also facilitates assessments of governmental performance in promoting health (Shi 2019). Throughout this book, health is defined as WHO defined it long ago, as its foundation has withstood the test of time:

Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

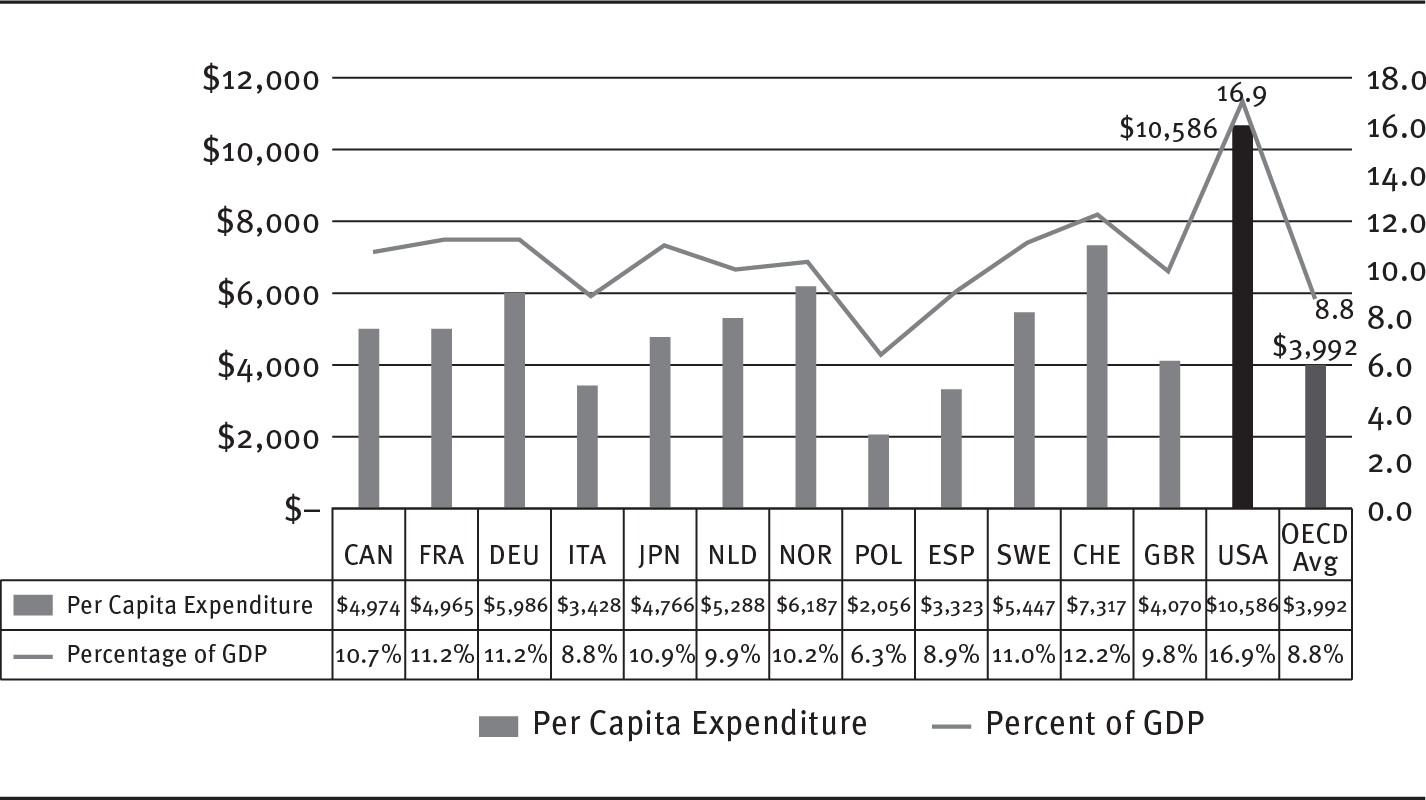

Health is important in all nations, although the resources available for its pursuit vary widely. Current international health expenditure comparisons for the member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), all of which share a commitment to democratic government and market economies, reflect some of this variation and are available online at www.oecd.org.

The relative importance that leaders and citizens of nations place on the health of their populations is partially reflected in the proportions of available resources devoted to the pursuit of health. Exhibit 1.4 shows per capita health spending and percentage of GDP devoted to health in selected countries.

EXHIBIT 1.4 2017 NHE of Selected OECD Countries per Capita and as a Percentage of GDP (in dollars)

Long Description

The x-axis shows selected countries. The y-axis on the left shows NHE in dollars from 0 to 12,000 in increments of 2,000. The y-axis on the right shows percentage from 0.0 to 18.0 in increments of 2.0 percent. The details of the bar graph for per capita expenditure and line graph for percentage of GDP for selected countries respectively are as follows:

- Canada: 4,974 dollars; 10.7 percent.

- France: 4,965 dollars; 11.2 percent.

- Germany: 5,986 dollars; 11.2 percent.

- Italy: 3,428 dollars; 8.8 percent.

- Japan: 4,766 dollars; 10.9 percent.

- Netherlands: 5,288 dollars; 9.9 percent.

- Norway: 6,187 dollars; 10.2 percent.

- Poland: 2,056 dollars; 6.3 percent.

- Spain: 3,323 dollars; 8.9 percent.

- Sweden: 5,447 dollars; 11.0 percent.

- Switzerland: 7,317 dollars; 12.2 percent.

- Great Britain: 4,070 dollars; 9.8 percent.

- USA: 10,586 dollars; 16.9 percent.

- OECD Average: 3,992 dollars; 8.8 percent.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2019).

The other important lesson in exhibit 1.4 is the clear “most expensive in the world” position of the United States in spending for healthcare services. By whatever measure, the US spends more on healthcare services than any other nation: in total dollars, dollars per capita, or percentage of the GDP. But does that spending represent value? Are we getting a good return for our investment? More about this later in the chapter, but the short answer for the moment is no: the US does not obtain good results, especially in light of costs, in a number of metrics intended to elucidate the quality of a healthcare system.

Over time, the United States has opted for policies resulting in the most expensive healthcare system in the world. Although it is beyond the scope of this book to address how and why that came to be, you will see some interesting comparisons in the following sections. Important to appreciating the role health policy plays in the pursuit of health is the fact that health is a function of several variables, referred to as health determinants. The existence of multiple determinants provides governments with a wide variety of ways to intervene in any society’s pursuit of health.

Health determinants are defined as factors that affect health or, more formally, as a “range of personal, social, economic, and environmental factors that influence health” both at the individual and population levels (HHS 2020). The question of what determines health in humans has been of interest for a long time.

An important early theory about the determinants of health was the Force Field paradigm (Blum 1974). In this theory, four major influences, or force fields, determine health: environment, lifestyle, heredity, and medical care. In another conceptualization, the determinants are divided into two categories (Dahlgren and Whitehead 2006). One category, named fixed factors, is unchangeable and includes such variables as age and gender. A second category, named modifiable factors, includes lifestyles, social networks, community conditions, environments, and access to products and services such as education, healthcare, and nutritious food.

The research on determinants of health, which is now extensive, has led to a holistic approach to health determinants. The determinants are catalytic with one another. For individuals and populations, health determinants include the physical environments in which people live and work; people’s behaviors; their biology (genetic makeup, family history, and acquired physical and mental health problems); social factors (including economic circumstances, socioeconomic position, and income distribution; discrimination based on such factors as race and ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation; and the availability of social networks or social support); and their access to health services. Exhibit 1.5 provides a visual representation of how these variables interact with one another, contributing to overall health. Scientists generally use the five determinants of health shown in exhibit 1.5 (CDC 2019).

EXHIBIT 1.5 Determinants of Health

A radial diagram with interlinked circles shows the factors of health determinants as physical environment, behaviors, biological factors, socioeconomic conditions, and access to care.

Source: Adapted from CDC (2019).

Another inclusive perspective on what factors determine health in humans is reflected in Healthy People 2020 (www.healthypeople.gov), a comprehensive national agenda for improving health. Note that there are slight differences between the determinants advanced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and those that are part of a national health agenda. Why the differences? No one knows for certain, but consider the fact that the US health system has two components: public health and healthcare services. Note that Healthy People 2020 is a function of the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion in HHS. This agency is engaged in the public health function of advocacy and, therefore, would consider policymaking to be a health determinant. The following box provides a list of health determinants and brief definitions adapted from Healthy People 2020 (HHS 2020).

Health Determinants

- Biology refers to the individual’s genetic makeup (those factors with which they are born), family history (which may suggest risk for disease), and physical and mental health problems acquired during life. Aging, diet, physical activity, smoking, stress, alcohol or illicit drug abuse, injury or violence, or an infectious or toxic agent may result in illness or disability and can produce a “new” biology for the individual.

- Behaviors are individual responses or reactions to internal stimuli and external conditions. Behaviors can have a reciprocal relationship with biology; in other words, each can affect the other. For example, smoking (behavior) can alter the cells in the lung and result in shortness of breath, emphysema, or cancer (biology), which then may lead an individual to stop smoking (behavior). Similarly, a family history that includes heart disease (biology) may motivate an individual to develop good eating habits, avoid tobacco, and maintain an active lifestyle (behaviors), which may prevent their own development of heart disease (biology).

- An individual’s choices and social and physical environments can shape their behaviors. The social and physical environments include all factors that affect the individual’s life—positively or negatively—many of which may be out of their immediate or direct control.

- Social environment includes interactions with family, friends, coworkers, and others in the community. It encompasses social institutions, such as law enforcement, the workplace, places of worship, and schools. Housing, public transportation, and the presence or absence of violence in the community are components of the social environment. The social environment has a profound effect on individual and community health and is unique for each individual because of cultural customs; language; and personal, religious, or spiritual beliefs. At the same time, individuals and their behaviors contribute to the quality of the social environment.

- According to the CDC, policymaking at the local, state, and federal level affects individual and population health. An increase in taxes on tobacco sales, for example, can improve population health by reducing the number of people using tobacco products. Some policies affect entire populations over extended periods of time while simultaneously helping to change individual behavior. For example, the 1966 Highway Safety Act and the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act authorized the federal government to set and regulate standards for motor vehicles and highways. This led to an increase in safety standards for cars, including seat belts, which in turn reduced rates of injuries and deaths from motor vehicle accidents.

- Public- and private-sector programs and interventions can have a powerful and positive effect on individual and community health. Examples include health promotion campaigns to prevent smoking; public laws or regulations mandating child restraints and seat belt use in automobiles; disease prevention services, such as immunization of children, adolescents, and adults; and clinical services such as enhanced mental health care. Programs and interventions that promote individual and community health, such as fitness or exercise programs, may be implemented by public agencies, including those that oversee transportation, education, energy, housing, labor, and justice, or through such private-sector endeavors as places of worship, community-based organizations, civic groups, and businesses.

- Quality health services can be vital to the health of individuals and communities. Expanding access to services could eliminate health disparities and increase the quality of life and life expectancy of all people living in the United States. Health services in the broadest sense include not only those received from health services providers but also health information and services received from other venues in the community.

Source: Adapted from HHS (2020).

Nations differ in the relative importance they assign to addressing the various determinants of health. For example, among the OECD nations, the United States ranks first in health expenditures but twenty-fifth in spending on social services. This expenditure pattern reflects a particular prioritization among determinants and is not necessarily the most cost-effective pattern. For example, the 1.5 million people in the United States who experience homelessness in any given year use disproportionately more costly acute care services (Doran, Misa, and Shah 2013).

Not only do nations prioritize health determinants differently, but people, as individuals and populations, vary in their health and health-related needs. The population of the United States is remarkably diverse in age, gender, race and ethnicity, income, and other factors. Current census data put the US population at approximately 327 million people; 16 percent of them are older than 65. Persons of Hispanic or Latino origin make up about 18.3 percent of the population, and African Americans constitute approximately 13.4 percent of the population (US Census Bureau 2019). These demographics are important when considering health and its pursuit.

Older people consume relatively more health services, and their health-related needs differ from those of younger people. Older people are more likely to consume long-term care services and community-based services intended to help them cope with various limitations in the activities of daily living.

In discussing health and the healthcare system, we frequently encounter populations of people—minorities and the poor in particular—who do not enjoy the same level of health as others or who do not have the same kind of access to care as others. These differences are referred to as disparities. Healthcare disparities and health disparities, although related, are not the same. Healthcare disparities refer to differences in such variables as access to care, insurance coverage, and quality of services received. Health disparities occur when one population group experiences higher burdens of illness, injury, death, or disability than another group.

The healthcare system continues to confront the challenge of eliminating health and healthcare disparities. There is evidence that the ACA contributed to reducing disparities that existed for Hispanics and African Americans (Hayes et al. 2017). In recent years, policymakers have paid greater attention to racial and ethnic disparities in care, with notable, although unfinished, progress. Congress directed the Institute of Medicine (IOM; www.iom.edu) to study health disparities and established the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities at the National Institutes of Health (NIH; www.nih.gov). Congress also required the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS; www.hhs.gov) to report annually on the nation’s progress in reducing healthcare disparities and health disparities (HHS 2014). There are some differences in how each agency sees “disparity” because one is dealing strictly with the science of health determination (NIH), while the other is also dealing with the disparities created in access to care (HHS).

The IOM (2002) report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care called for a multilevel strategy to address potential causes of racial and ethnic healthcare disparities, including

- raising public and provider awareness of racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare,

- expanding health insurance coverage,

- improving the capacity and quantity of providers in underserved communities, and

- increasing understanding of the causes of and interventions to reduce disparities.

Progress in pursuing this multifaceted strategy continues, and it received a substantial boost from the passage of the ACA. Among the ACA’s numerous goals, two of the most important are to reduce the number of uninsured people and to improve access to healthcare services for all citizens (Garfield, Orgera, and Damico 2019; Williams 2011).

In spite of progress, continued racial disparity is easily identified. For example, an African American woman is 22 percent more likely to die from heart disease than her white counterpart, 71 percent more likely to die from cervical cancer, and 243 percent more likely to die from pregnancy- and childbirth-related causes (Hostetter and Klein 2018). As a matter of equity, statistics like these are unacceptable.

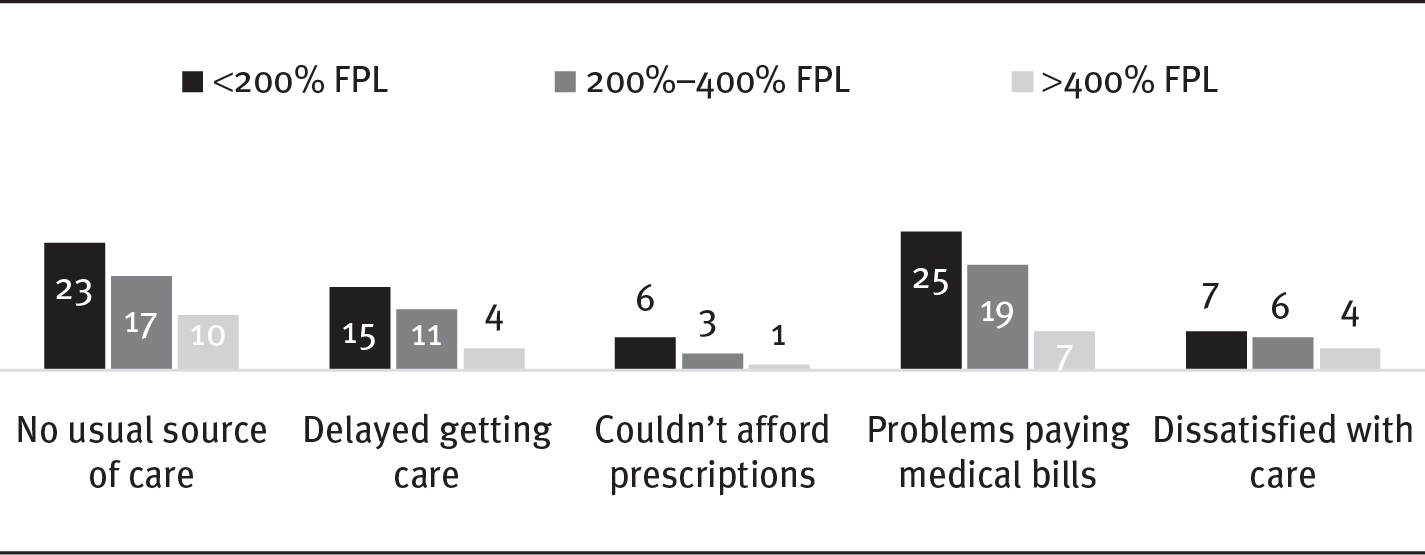

Researchers are learning more about how health status is affected by income and other socioeconomic factors. Wealthier Americans tend to be in better health than their poorer counterparts primarily because of differences in education, behavior, and environment. Higher incomes permit people to buy healthier food; live in safer, cleaner neighborhoods; and exercise regularly (Luhby 2013). Exhibit 1.6 demonstrates this absence of equity in terms of access to care relative to income: the higher the income, the more likely one is to be able to access care, receive care, and be more satisfied with the care one receives.

EXHIBIT 1.6 Access to Care by Income Level Relative to Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

Long Description

The details of the chart are as follows:

- No usual source of care:

- Lesser than 200 percent FPL: 23

- 200 to 400 percent FPL: 17

- Greater than 400 percent FPL: 10.

- Delayed getting care:

- Lesser than 200 percent FPL: 15

- 200 to 400 percent FPL: 11

- Greater than 400 percent FPL: 4.

- Couldn’t afford prescriptions:

- Lesser than 200 percent FPL: 6

- 200 to 400 percent FPL: 3

- Greater than 400 percent FPL: 1.

- Problems paying medical bills:

- Lesser than 200 percent FPL: 25

- 200 to 400 percent FPL: 19

- Greater than 400 percent FPL: 7.

- Dissatisfied with care:

- Lesser than 200 percent FPL: 7

- 200 to 400 percent FPL: 6

- Greater than 400 percent FPL: 4.

Source: Commonwealth Fund (2018).

However, low income does not necessarily mean poorer health. In part, the impact of income depends on what government does about supporting people with low incomes. A national survey has shown that the income variable interacts importantly with the extant health policy in the various states (Schoen et al. 2013). Using 30 indicators of access, outcomes, prevention, and quality, the survey documents sharp healthcare disparities among states, revealing up to a fourfold disparity in performance for low-income populations. The most important conclusion of this survey is that “if all states could reach the benchmarks set by leading states, an estimated 86,000 fewer people would die prematurely and tens of millions more adults and children would receive timely preventive care” (Schoen et al. 2013).

Although its population is diverse, several widely, though not universally, shared values directly affect the approach to healthcare in the United States. For example, many Americans place a high value on individual autonomy, self-determination, and personal privacy and maintain a widespread, although not universal, commitment to justice. Other societal characteristics that have influenced the pursuit of health in the United States include a common deep-seated belief in the potential of technological rescue and a cultural preference for the prolonging of individual life regardless of the monetary costs (although this attitude is changing). These values shape the private and public sectors’ efforts related to health, including the elaboration of public policies germane to health and its pursuit. They also influence the prioritization of attention to the various determinants of health.

Defining Health Policy

A suitable context is necessary to understand the essence of health policy fully. First, it is important to realize that policy is made in both the private sector and the public, or governmental, sector. Policy is made in all sorts of organizations, including corporations such as Google, institutions such as the Mayo Clinic, health insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, and governments at federal, state, and local levels. In all settings, policies are officially or authoritatively made decisions for guiding actions, decisions, and behaviors of others (Longest and Darr 2014). The decisions are official or authoritative because they are made by people who are entitled to make them based on their positions in their entities. Executives and other managers of corporations and institutions are entitled to establish policies for their organizations because they occupy certain positions. Similarly, in the public sector, certain people are positionally entitled to make policies. For example, members of Congress are entitled to make certain decisions, as are executives in government or members of the judiciary.

Policies made in the private sector can certainly affect health. Examples include authoritative decisions made in the private sector by executives of healthcare organizations about such issues as their product lines, pricing, and marketing strategies. Insurance companies also fall into this group, as they determine the breadth and depth of the coverage they provide. Official or authoritative decisions made by such organizations as The Joint Commission (www.jointcommission.org), a private accrediting body for health-related organizations, and the National Committee for Quality Assurance (www.ncqa.org), a private organization that assesses and reports on the quality of managed care plans, are also private-sector health policies. This book focuses on the public policymaking process and the public-sector health policies that result from this process. Private-sector health policies, however, also play vital roles in the ways societies pursue health.

Public Policy

There are many definitions of public policy but no universal agreement on which is best. For example, Peters (2013, 4) defines public policy as the “sum of government activities, whether acting directly or through agents, as those activities have an influence on the lives of citizens.” Birkland (2001) defines it as “a statement by government of what it intends to do or not to do, such as a law, regulation, ruling, decision, or order, or a combination of these.” Cochran and Malone (1999) propose yet another definition: “Political decisions for implementing programs to achieve societal goals.” Drawing on these and many other definitions, we define public policy in this book as

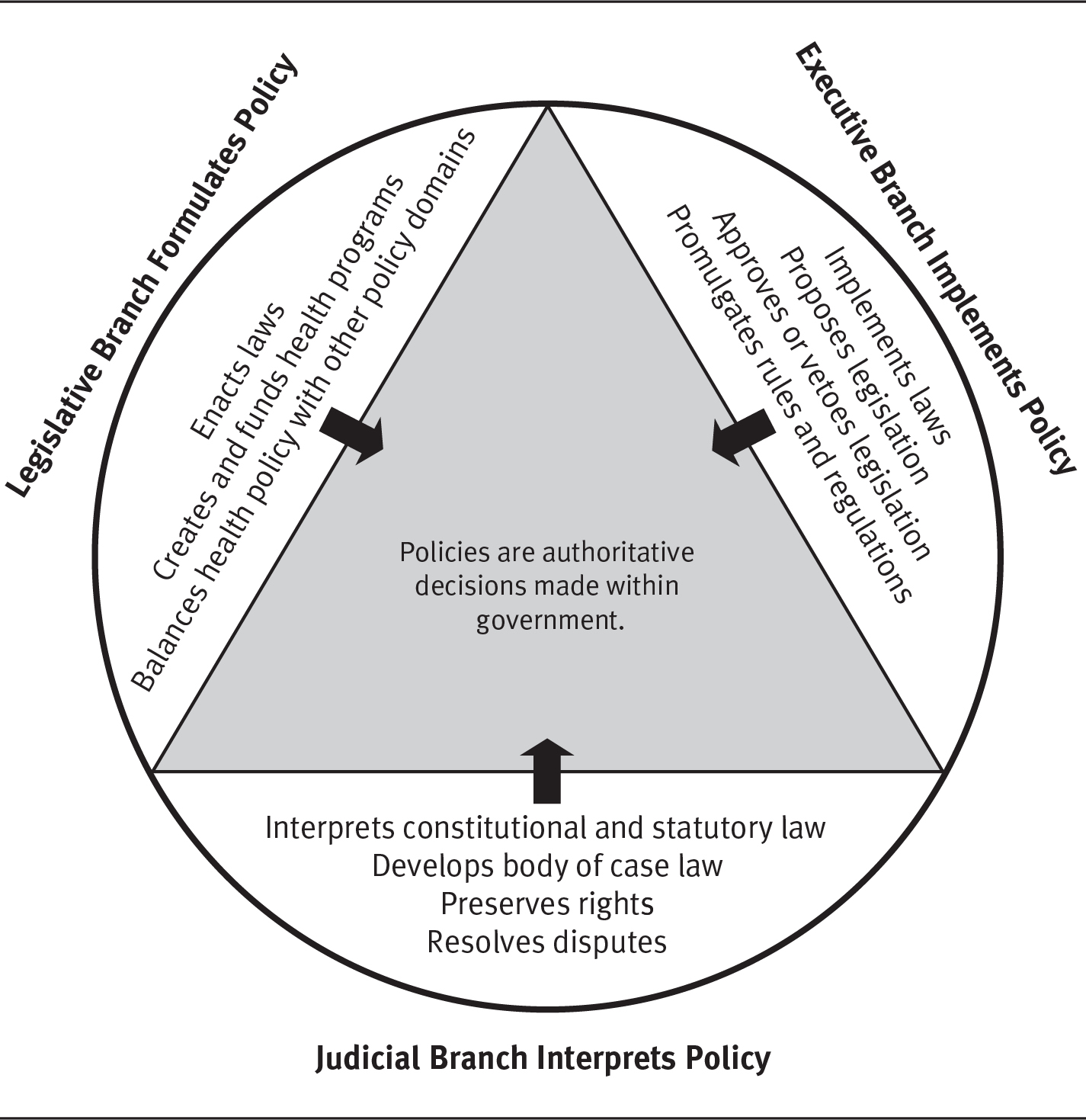

authoritative decisions made in the legislative, executive, or judicial branches of government that are intended to direct or influence the actions, behaviors, or decisions of others.

The phrase authoritative decisions is crucial in this definition. It specifies decisions made anywhere in the three branches of government—and at any level of government—that are within the legitimate, official purview of those making the decisions. The decision-makers can be legislators, executives of government (presidents, governors, cabinet officers, heads of agencies), or judges. Part of these roles is the legitimate right—indeed, the responsibility—to make certain decisions. Legislators are entitled (and expected) to decide on laws, executives to decide on rules to implement laws, and judges to review and interpret decisions made by others. Exhibit 1.7 illustrates these relationships in conceptual form, while the policy snapshot at the beginning of part 1 demonstrates how this looks in the real world.

EXHIBIT 1.7 Roles of Three Branches of Government in Policymaking

Long Description

The triangle in the middle shows that policies are authoritative decisions made within government. The decision-makers shown surrounding the triangle are legislators, executives, or judges of government. The details are as follows:

- Legislative Branch Formulates Policy: Enacts laws, creates and funds health programs, balances health policy with other policy domains.

- Executive Branch Implements Policy: Implements laws, proposes legislation, approves or vetoes legislation, promulgates rules and regulations.

- Judicial Branch Interprets Policy: Interprets constitutional and statutory law, develops body of case law, preserves rights, resolves disputes.

In the United States, public policies—whether they pertain to health or to defense, education, transportation, or commerce—are made through a dynamic public policymaking process. This process, which is discussed in chapter 3, involves interaction among many participants in three interconnected phases: formulation, implementation, and modification.

Health Policy

Health policy is but a particular version of public policy. Public policies that pertain to health or influence the pursuit of health are health policies. Thus, we can define public-sector health policy as

authoritative decisions regarding health or the pursuit of health made in the legislative, executive, or judicial branches of government that are intended to direct or influence the actions, behaviors, or decisions of others.

In the policy snapshot introducing part 1, “The Affordable Care Act: A Cauldron of Controversy,” Congress and the executive branch sought to influence the behavior of (a) individuals with regard to the individual mandate and (b) the states with regard to the expansion of Medicaid. The Supreme Court altered the application (and resulting impact) of those initiatives by interpreting the law against the backdrop of the US Constitution.

Health policies are established at federal, state, and local levels of government, although usually for different purposes. Generally, a health policy affects or influences a group or class of individuals (e.g., physicians, the poor, the elderly, children), or a type or category of organization (e.g., medical schools, health plans, integrated delivery and financing [risk bearing or insurance] systems, freestanding healthcare organizations, pharmaceutical manufacturers, employers).

At any given time, the entire set of health-related policies made at any level of government constitutes that level’s health policy. Thus, a government’s health policy is a large set of authoritative decisions made through the public policymaking process. Throughout this book, we will say much more about health policy, its context, and the process by which these decisions are made. Much of what can be said about health policy in the United States is positive. People are healthier because of the impact of many health policies. However, the United States faces significant challenges in its efforts to improve the health of its people. The US healthcare system continues to be fractured, complex, often duplicative, and arguably both inefficient and ineffective. Although many health policies have had enormous benefit (e.g., Medicare for the elderly and those with disabilities, advances in science and technology fostered by public funding), many challenges remain, and the healthcare delivery system remains Kafkaesque with misaligned incentives. Policies, which are decisions made by humans, can be good (with positive consequences) or misguided (with negative or unintended consequences). As of this writing, government policy encourages new payment mechanisms, along with new clinical relationships, that are changing—improving—the way health services are delivered. Observers have noted a number of encouraging signs about modernizing the culture of healthcare services.

There is no shortage of thoughtful assessments of what health policy should achieve. One excellent set of measures regarding what it should do in the area of healthcare delivery and financing comes from the Partnership for Sustainable Health Care (2013), a diverse group of healthcare stakeholders including the hospital, business, consumer, and insurance sectors. Brought together under the auspices of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; www.rwjf.org), this group envisions “a high-performing, accountable, coordinated health care system where patient experience and population health are improved, and where per-capita health care spending is reduced.” The specific elements of their vision for healthcare in the United States are as follows:

- Health care that is affordable and financially sustainable for consumers, purchasers, and taxpayers

- Patients who are informed, empowered, and engaged in their care

- Patient care that is evidence based and safe

- A delivery system that is accountable for health outcomes and resource use

- An environment that fosters a culture of continuous improvement and learning

- Innovations that are evaluated for effectiveness before being widely and rapidly adopted

- Reliable information that can be used to monitor quality, cost, and population health (Partnership for Sustainable Health Care 2013)

The ACA held promise for achieving, at least in part, these and other goals through improved policy. However, implementation of many aspects of the ACA has proven difficult (Jost 2014; Thompson 2013). While it is unnecessary to complete a thorough review of the ACA’s outcomes here, it bears mentioning that assessing its impact on the elements of healthcare’s “iron triangle” of cost, quality, and access is important. Suffice it to say that the ACA has expanded the number of people with insurance coverage and appears to have made some progress in the quality domain by funding wellness visits, emphasizing vaccinations, and using payment mechanisms to encourage a higher degree of clinical integration and cooperation.

As with any new law or program, however, the effectiveness of achieving legislative goals relies on how the executive branch implements and administers the law. At its outset, the ACA, an initiative of the Obama administration, had the full support of the president and his executive team. That administration actively promoted the health insurance exchanges and enrollment in plans available through them. Between those efforts and the expansion of Medicaid, 21 million people not previously insured became beneficiaries. For them, at least one barrier to access had been removed. Subsequently, however, a new president was elected in 2016 who had a different idea about healthcare services, financing, and delivery. After entering office, President Donald Trump reduced or eliminated previous promotional efforts. Consequently, the number of newly insured Americans has declined (Jones et al. 2018; Kaiser Family Foundation 2018a; Rice et al. 2018).

Some countries, most notably Canada and Great Britain, have developed expansive, well-integrated policies to fundamentally shape their societies’ pursuit of health (Ogden 2012). Instead, the traditional approach to health policy in the United States has been incremental. On occasion, there are significant events, such as the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid. But even those programs were built on legislative foundations already in place. As a result, the United States has only a few large health-related policies.

Even the ACA, for all of its complexity and breadth, makes mostly incremental changes in the healthcare delivery system: expansion of Medicaid, tax credits for individuals to buy insurance, extending private insurance availability through health insurance exchanges, among others. In essence, the ACA built on the existing Medicaid infrastructure, as well as the private insurance markets. The net result is a large number of policies, few of which have dealt with the pursuit of health in a broad, comprehensive, or integrated way until linked together in a single initiative such as the ACA. Legal and political challenges to the ACA have been frequent occurrences, as we saw in “A Cauldron of Controversy.” To date, the various constitutional challenges to the ACA largely have been unsuccessful, and most legislative attacks on its component parts have been defeated—with notable exceptions, such the repeal of the “Cadillac tax” on high-value health insurance plans (Will 2019). The shared responsibility payment imposed on individuals for failing to comply with the individual mandate of insurance coverage has also been repealed following the election of 2016 (Jost 2017).

The fundamental challenge to the US healthcare services delivery system today is to increase value to the consumer by restraining cost increases—while becoming more effective in delivering care. In short, deliver a higher quality of care for smaller increases in costs. This necessity is intrinsic. In Crossing the Quality Chasm, the IOM ultimately defined six domains of healthcare quality, saying healthcare should be safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. Whether one uses the RWJF standards or the IOM’s six domains, the goal remains the same: to improve the quality of healthcare services available to people in the United States.

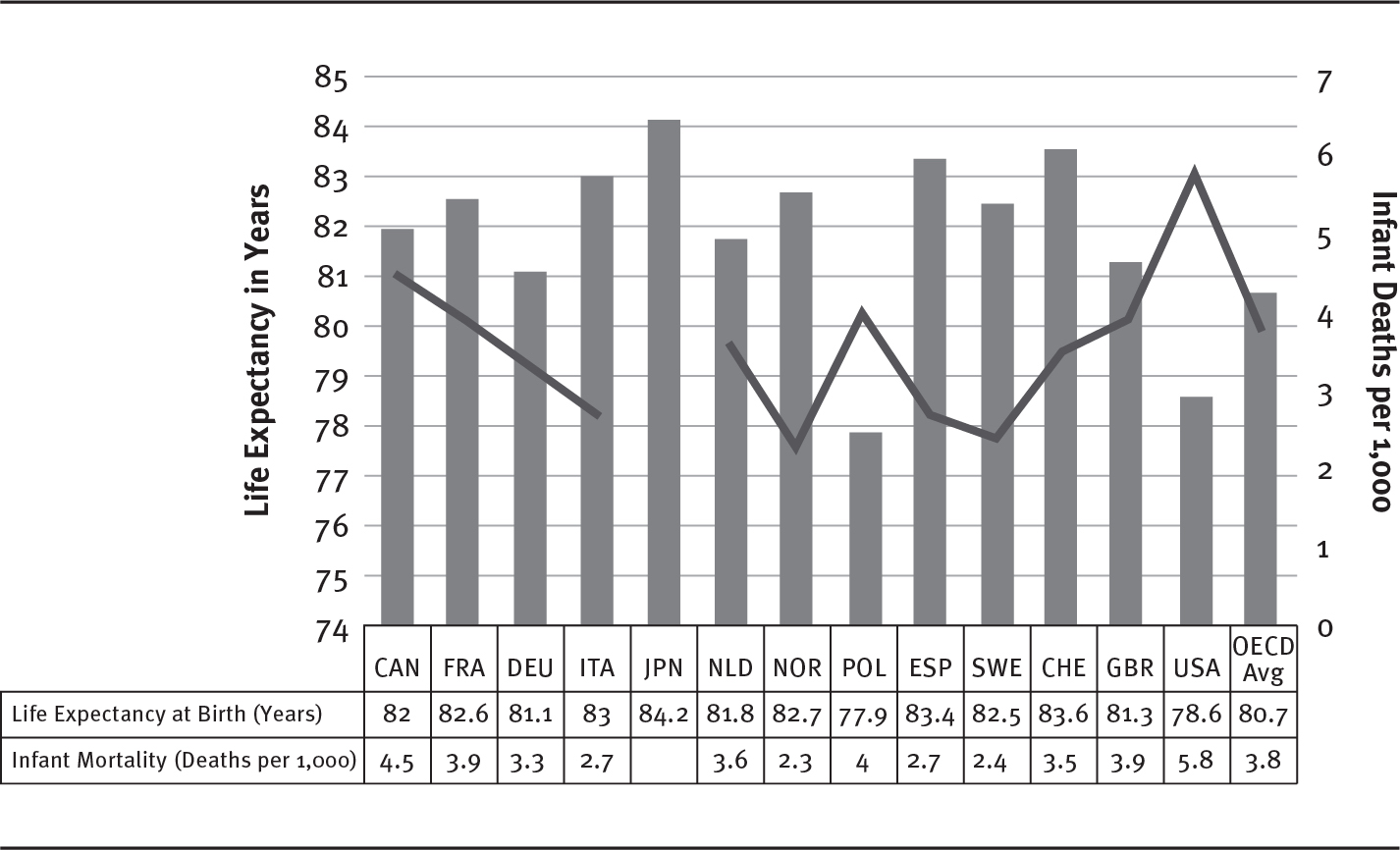

A wide variety of stakeholders benefits from improved care, by either definition: payers, providers, patients, and others would all benefit from the kind of care described by IOM or RWJF. There remains, however, an extrinsic factor to consider as well. When we discussed costs earlier, we made some international comparisons. Here is the question: If we are spending more for healthcare services than anyone in the world by any measure, do we have the best healthcare system in the world? Regrettably, the answer is no. As shown in exhibit 1.8, the United States has relatively poor rankings in two of the most common standard measurements used to demonstrate the quality of a healthcare delivery system. Note that these are the same countries for which NHE comparisons were made in exhibit 1.4.

EXHIBIT 1.8 Selected OECD Countries: Life Expectancy at Birth (in Years) and Infant Mortality (Deaths per 1,000) in 2017

Long Description

The x-axis shows selected countries. The y-axis on the left shows life expectancy in years from 74 to 85 in increments of 1 year. The y-axis on the right shows percentage of infant death per 1,000 from 0 to 7 in increments of 1 percent. The details of the bar graph for life expectancy and line graph for percentage of infant death for selected countries respectively are as follows:

- Canada: 82; 4.5 percent.

- France: 82.6; 3.9 percent.

- Germany: 81.1; 3.3 percent.

- Italy: 83; 2.7 percent.

- Japan: 84.2; no data.

- Netherlands: 81.8; 3.6 percent.

- Norway: 82.7; 2.3 percent.

- Poland: 77.9; 4 percent.

- Spain: 83.4; 2.7 percent.

- Sweden: 82.5; 2.4 percent.

- Switzerland: 83.6; 3.5 percent.

- Great Britain: 81.3; 3.9 percent.

- USA: 78.6; 5.8 percent.

- OECD Average: 80.7; 3.8 percent.

Note: No data provided for Japanese infant mortality rate.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2019).

The point of this comparison is to invite you to think about how effective US policy is as it relates to health. If US policy supports the initiatives as described by RWJF and the IOM, then indicators such as those shown here should improve over time. While this chapter has only presented two indicators to compare, students are invited to ruminate on this issue for themselves (for more information, see www.commonwealthfund.org).

With the enactment of the ACA, the United States entered a period of major national health reform. The healthcare system has been described accurately as “unsustainable” and “flawed” and is characterized by uncontrolled costs, variable quality, and millions of uninsured and underinsured people. Whether the ACA can solve all that there is to solve is unlikely. It has, however, moved the United States toward a greater degree of clinical integration, expanded insurance coverage, and a renewed focus on quality through the study of comparative effectiveness and payment mechanisms that reward good quality performance.

Forms of Health Policies

Health policies, which we defined earlier as authoritative decisions, take several basic forms (see exhibit 1.7). Some policies are decisions made by legislators that are codified in the statutory language of specific pieces of enacted legislation—in other words, laws. Federal public laws are given a number that designates the enacting Congress and the sequence in which the law was enacted. P.L. 89-97, for example, means that this law was enacted by the Eighty-Ninth Congress and was the ninety-seventh law passed by that Congress. A briefly annotated chronological list of important federal laws pertaining to health can be found in chapter 3.

Policies can take several forms:

- Laws

- Rules or regulations

- Implementation decisions

- Judicial decisions

Stemming from laws are rules or regulations established to implement the laws. Whereas laws are policies made in the legislative branch, rules or regulations are policies made in the executive branch. Both are important forms of policies. A third form of public policies includes numerous decisions made authoritatively by government officials, organizations, and agencies as they implement laws and operate the government and its programs. Policies in the form of implementation decisions are in addition to formal rules or regulations and are typically made by the same executive branch members who establish rules or regulations. Still other policies are the judicial branch’s decisions.

Selective examples of health policies include

- the 2010 federal public law P.L. 111-148 (the ACA);

- an executive order regarding operation of federally funded health centers;

- a federal court’s ruling that an integrated delivery system’s acquisition of yet another hospital violates federal antitrust laws;

- a state government’s procedures for licensing physicians;

- a county health department’s procedures for inspecting restaurants; and

- a city government’s ordinance banning smoking in public places within its borders.

Laws

Laws enacted at any level of government are policies. One example of a federal law is the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-85), which amended the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to revise and extend the user-fee programs for prescription drugs and medical devices. Another example is the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-354), which created an optional Medicaid category for low-income women diagnosed with cancer through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (www.cdc.gov) breast and cervical cancer early detection screening program. State examples include laws that govern the licensure of health-related practitioners and institutions. When laws trigger elaborate efforts and activities aimed at implementing the law, the whole endeavor is called a program. The Medicare program is a federal-level example. Many laws, most of which are amendments to prior laws, govern this vast program.

Policy, Law, and Technology: An Example

Policy objectives (e.g., improved women’s health services) are achieved, in part, through the passage of legislation (law) intended to advance research for imaging and biomedical devices (technology) that, when used, will provide additional protection for women against cancer. The National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering Establishment Act of 2000 is an example of such a causal relationship. This law established the eponymously named institute to accelerate the development and application of biomedical technologies. Electronic versions of this and other federal laws dating back to 1973, the ninety-third Congress, can be found at www.congress.gov, a website maintained by the Library of Congress that provides access to official federal legislative information.

Rules or Regulations

Rules and regulations (the terms are used interchangeably in the policy context) are another form of public policy established by administrative agencies responsible for implementing laws. Administrative agencies, whether created by the US Constitution, Congress, or a state legislature, are official governmental bodies authorized and empowered to implement laws. These governmental bodies come in many forms, including agencies, departments, divisions, commissions, corporations, and boards. In this book, we will refer to them most often simply as implementing organizations and agencies. In chapter 8, which discusses the role of courts in policymaking, these bodies are referred to primarily as administrative agencies because that is the more widely used term in professional and legal fields. More information about implementing organizations or agencies, and more about rules and rulemaking, is provided in chapter 7.

The Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 defined rule as “the whole or part of an agency statement of general or particular applicability and future effect designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law,” a definition that still stands. Because such rules are authoritative decisions made in the executive branch of government by the organizations and agencies responsible for implementing laws, they fit the definition of public policies. The rules associated with the implementation of complex laws routinely fill hundreds and sometimes thousands of pages. Rulemaking, the processes through which executive branch agencies write the rules to guide law implementation, is an important activity in policymaking and is discussed in detail in chapter 7.

Rules, in proposed form (for review and comment by those who will be affected by them) and in final form, are published in the Federal Register (FR; www.federalregister.gov), the official daily publication for proposed and final rules, notices of federal agencies, and executive orders and other presidential documents. The FR is published by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration.

Part 3 of this book will discuss rules and regulations in detail, including an example of a proposed rule.

Implementation Decisions

When organizations or agencies in the executive branch of any level of government implement laws, they must make numerous decisions about how to implement the rules and regulations that flow from the legislative authority. These are influential decisions that, although different from the formal rules that influence implementation, are policies as well. For example, effectively managing Medicare requires the federal government to undertake a complex and diverse set of management tasks, including the following:

- Implementing and evaluating Medicare policies and operations

- Identifying and proposing modifications to Medicare policies

- Managing and overseeing Medicare Advantage and prescription drug plans, Medicare fee-for-service providers, and contractors

- Collaborating with key stakeholders in Medicare (i.e., plans, providers, other government entities, advocacy groups, consortia)

- Developing and implementing a comprehensive strategic plan to carry out Medicare’s mission and objectives

- Identifying program vulnerabilities and implementing strategies to eliminate fraud, waste, and abuse in Medicare

In carrying out these tasks, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS; www.cms.gov), the agency responsible for implementing the Medicare and Medicaid programs as well as many aspects of the ACA, makes myriad decisions about implementation. Again, because they are authoritative, these decisions are policies.

Judicial Decisions

As noted in the policy snapshot, judicial decisions are another form of policy. Another example is the Supreme Court’s 2008 MetLife v. Glenn decision regarding how federal courts reviewing claims denials by plan administrators under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act “should take into account the fact that plan administrators (insurers and self-insured plans) face a conflict of interest because they pay claims out of their own pockets and arguably stand to profit by denying claims” (Jost 2008, w430). These decisions are policies because they are authoritative and direct or influence the actions, behaviors, or decisions of others. Still another example is King v. Burwell, which upheld a section of the ACA providing tax credit subsidies to certain purchasers of insurance (Hickman 2015).

King v. Burwell, 536 S.Ct. 2480 (2015): Highlighting Three Types of Policies

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, among other things, amended Section 36B of the Internal Revenue Code to provide tax credits for certain individuals purchasing health insurance through “an Exchange operated by the State.” The Internal Revenue Service (IRS), following the process for adopting administrative rules and regulations in the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 (discussed earlier in the chapter) interpreted Congress’s language to include exchanges operated by the federal government. Several taxpayers sued, ultimately taking the case to the Supreme Court, which upheld the IRS interpretation (Gamage 2015). Thus, similar to the policy snapshot, we see policy as expressed legislatively in the statute, interpreted and enforced by the administrative agency, and further interpreted and upheld by the judicial branch. (King v. Burwell is a significant case and will be discussed further in part 4).

Although the judicial branch of government has played an important role in health policy for decades, its role is increasingly relevant. For example, as we saw in the policy snapshot, in National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) v. Sebelius, the US Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that the ACA was indeed constitutional. This ruling was a crucial milestone for the law, permitting it to proceed (Liptak 2012). Its rationale and importance will be discussed in detail in chapter 8, which is devoted to the vital role played by the judiciary in health policy.

Categories of Health Policies

All policies, whether law, rule or regulation, implementation decision, or judicial decision, can be categorized in various ways. One approach divides policies into distributive, redistributive, and regulatory categories (Birkland 2001). Sometimes the distributive and redistributive categories are combined into an allocative category; sometimes the regulatory category is subdivided into competitive regulatory and protective regulatory categories. For our purposes, all of the various forms of health policies fit into two basic categories—allocative or regulatory.

In market economies, such as that of the United States, the presumption is that private markets best determine the production and consumption of goods and services, including health services. Of course, when markets fail and the economy slips into a recession, as they have several times in the last few decades, government intervention becomes essential. In market economies, government generally intrudes with policies only when private markets fail to achieve desired public objectives. The most credible arguments for policy intervention in the nation’s domestic activities begin with the identification of situations in which markets are not functioning properly.

The health sector is especially prone to situations in which markets function poorly. Theoretically perfect (i.e., freely competitive) markets, which do not exist in reality but provide a standard against which real markets can be assessed, require that

- buyers and sellers have sufficient information to make informed decisions,

- a large number of buyers and sellers participate,

- additional sellers can easily enter the market,

- each seller’s products or services are satisfactory substitutes for those of its competitors, and

- the quantity of products or services available in the market does not swing the balance of power toward either buyers or sellers.

The markets for health services in the United States violate these requirements in several ways. The complexity of health services reduces consumers’ ability to make informed decisions without guidance from the sellers or other advisers. Entry of sellers into the markets for health services is heavily regulated, and widespread insurance coverage affects the decisions of buyers and sellers. These and other factors mean that markets for health services frequently do not function competitively, thus inviting policy intervention.

Furthermore, the potential for private markets on their own to fail to meet public objectives is not limited to production and consumption. For example, markets on their own might not stimulate sufficient socially desirable medical research or the education of enough physicians or nurses without policies that subsidize certain costs associated with these ends. These and similar situations provide the philosophical basis for the establishment of public policies to correct market-related problems or shortcomings.

The nature of the market problems or shortcomings directly shapes the health policies intended to overcome or ameliorate them. Based on their primary purposes, health policies fit broadly into allocative or regulatory categories, although the potential for overlap between the two categories is considerable.

Allocative Policies

Allocative policies provide net benefits to some distinct group or class of individuals or organizations at the expense of others to meet public objectives. Such policies are, in essence, subsidies through which policymakers seek to alter demand for or supply of particular products and services or to guarantee certain people access to them. For example, government has heavily subsidized the medical education system on the basis that without subsidies to medical schools, markets would undersupply physicians. Similarly, for many years, under the aegis of the Hill-Burton Act, the federal government subsidized the construction of hospitals on the basis that markets would undersupply hospitals in sparsely populated or low-income areas.

Other subsidies have been used to ensure that certain people have access to health services (see box on the Sheppard-Towner Act). A key feature of the ACA is its subsidization of health insurance coverage, in the form of tax credits, for millions of people. Preceding the ACA and continuing into the future, however, the Medicare and Medicaid programs have been massive allocative policies. Medicare expenditures will be more than $1 trillion in 2022, and Medicaid expenditures could surpass $732 billion by then (CMS 2020a).

Federal funding to support access to health services for Native Americans, veterans, and migrant farmworkers and state funding for mental institutions are other examples of allocative policies that are intended to help individuals gain access to needed services. Although some subsidies are reserved for the people who are most impoverished, subsidies such as those that support medical education, the Medicare program (the benefits of which are not based primarily on financial need), the expansive subsidies in the ACA, and the exclusion of employer-provided health insurance benefits from taxable income illustrate that poverty is not necessarily a requirement to be the beneficiary of an allocative policy.

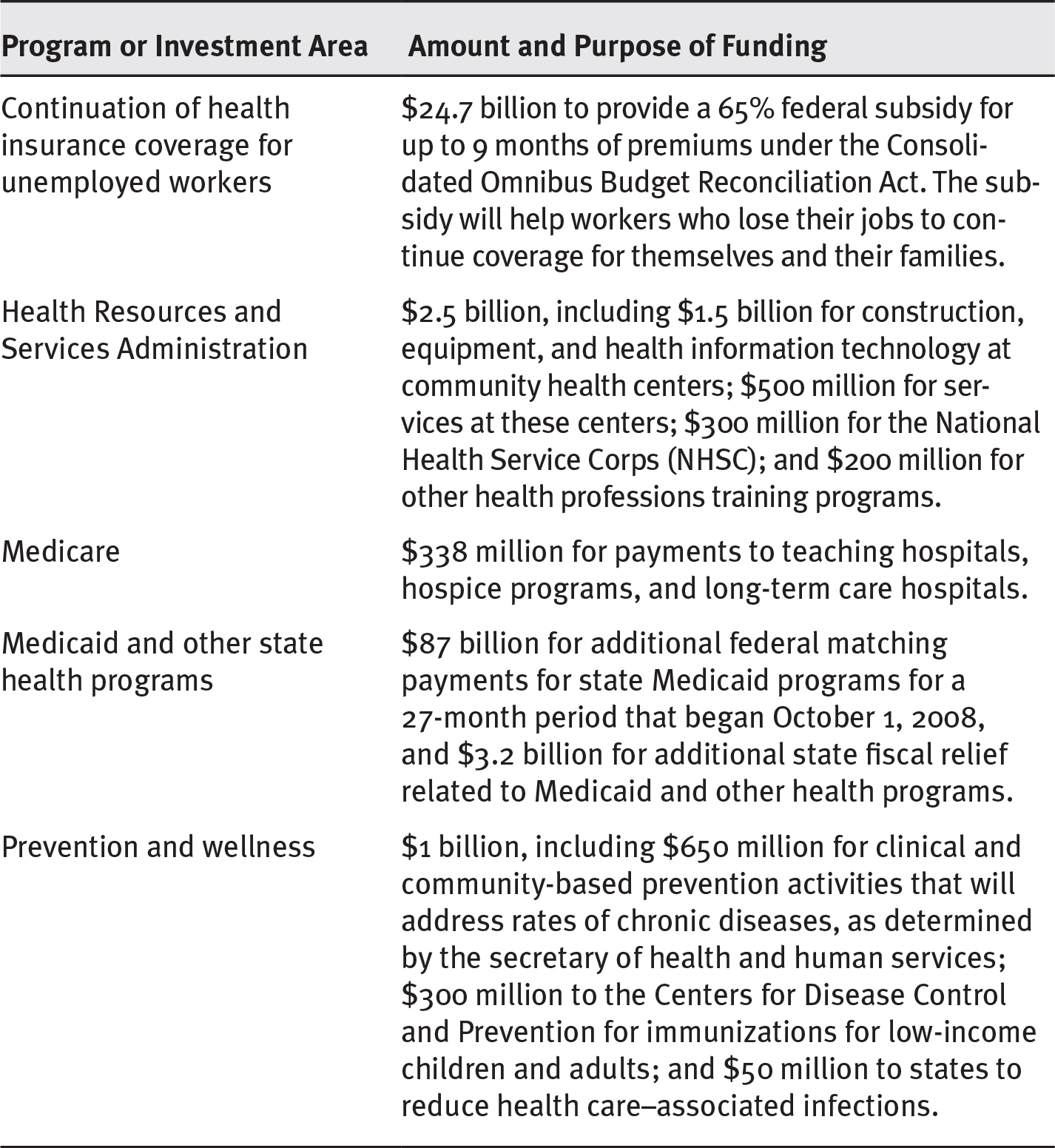

Some of the provisions of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5) provide examples of allocative policy. This law, enacted in response to the global financial crisis that emerged in 2008, contains many health-related subsidies. Exhibit 1.9 lists some examples.

EXHIBIT 1.9 Examples of Health-Related Subsidies Included in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

Long Description

The details of the program or investment area and the subsidized amount and purpose of funding are as follows:

- Continuation of health insurance coverage for unemployed workers: 24.7 billion dollars to provide a 65 percent federal subsidy for up to 9 months of premiums under the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. The subsidy will help workers who lose their jobs to continue coverage for themselves and their families.

- Health Resources and Services Administration: 2.5 billion dollars, including 1.5 billion dollars for construction, equipment, and health information technology at community health centers; 500 million dollars for services at these centers; 300 million dollars for the National Health Service Corps (NHSC); and 200 million dollars for other health professions training programs.

- Medicare: 338 million dollars for payments to teaching hospitals, hospice programs, and long-term care hospitals.

- Medicaid and other state health programs: 87 billion dollars for additional federal matching payments for state Medicaid programs for a 27-month period that began October 1, 2008, and 3.2 billion dollars for additional state fiscal relief related to Medicaid and other health programs.

- Prevention and wellness: 1 billion dollars, including 650 million dollars for clinical and community-based prevention activities that will address rates of chronic diseases, as determined by the secretary of health and human services; 300 million dollars to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for immunizations for low-income children and adults; and 50 million dollars to states to reduce health care–associated infections.

Source: R. Steinbrook, 2009, “Health Care and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act,” New England Journal of Medicine 360 (11): 1057–60. Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

The Sheppard-Towner Act: An Important Policy and a Lasting Legacy

The first major legislation to pass in the aftermath of the women’s suffrage movement was the Maternity and Infancy Act (P.L. 67-97), also known as Sheppard-Towner (for the two sponsors of the act). One of the novel features of this law was the use of federal tax revenue distributed on a formulaic basis as an incentive for the states. This act marked the first use of formulaic distribution of federal money in the healthcare arena. In this case, the federal government provided money for, among other things, development of state-level birth registries and aid for impoverished children. At the time of Sheppard-Towner’s passage in 1922, 30 states, representing 76 percent of the births nationally, had birth registries. In 1929, when Congress opted not to renew the act, those statistics had risen to 46 states representing 95 percent of the births in the United States (Kotch 1997). Even in nonrenewal, however, Sheppard-Towner left a legacy.

The matching grant technique that the act debuted gets recycled in many domains, including healthcare. Examples include not only the expansion of Medicaid in the ACA, but Medicaid itself. Similarly, many of the other policy provisions of Sheppard-Towner have proven to be the historical antecedent or direct model for contemporary policy. Sheppard-Towner may have introduced many important innovations, but in the matching grant provision we see the power of an allocative policy to induce states to behave in certain ways intended to improve public health and, in particular, the health status of at-risk children.

Regulatory Policies

Regulatory policies are designed to influence the actions, behaviors, and decisions of others by directive. All levels of government establish regulatory policies. As with allocative policies, government establishes such policies to ensure that public objectives as established by the policy process are met. Following are the five basic categories of regulatory health policies:

- Market entry–restricting regulations include licensing of health-related practitioners and organizations. Planning programs, through which preapproval for new capital projects by health services providers, such as certificate of need (CON), must be obtained, are also market entry–restricting regulations.

- Price or rate-setting regulations, although generally out of favor, exert control over some aspects of the pursuit of health. The federal government’s control of the rates at which it reimburses hospitals for care provided to Medicare patients and its establishment of a fee schedule for reimbursing physicians who care for Medicare patients are examples.

- Quality-control regulations are those intended to ensure that health services providers adhere to acceptable levels of quality in the services they provide and that producers of health-related products, such as imaging equipment and pharmaceuticals, meet safety and efficacy standards. For example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is charged with ensuring that new pharmaceuticals meet these standards. In addition, the Medical Devices Amendments (P.L. 94-295) to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (P.L. 75-717) placed all medical devices under a comprehensive regulatory framework administered by the FDA.

- Market-preserving controls are necessary because the markets for health services do not behave in truly competitive ways. For that reason, government establishes and enforces rules of conduct for participants. Antitrust laws such as the Sherman Antitrust Act, the Clayton Act, and the Robinson-Patman Act—which are intended to maintain conditions that permit markets to work well and fairly—are good examples of this type of regulation.

- Social regulation, the fifth category of healthcare policy, is a regulatory effort to achieve socially desirable outcomes such as workplace safety and fair employment practices and to reduce undesirable outcomes such as pollution or sexually transmitted disease. The first four classes of regulations are all variations of economic regulation. Social regulation usually has an economic effect, but this is not the primary purpose. Federal and state laws pertaining to environmental protection, disposal of medical wastes, childhood immunization, and the mandatory reporting of communicable diseases are examples of social regulations at work in the pursuit of health.

Sometimes polices are in conflict—differing objectives collide. When this happens, the conflict must be mediated in one way or another to facilitate the objectives of one policy or another. For example, Congress, through the ACA, created accountable care organizations (ACOs) to promote clinical integration. The idea is to promote quality of care (as well as restrain costs), so the ACA functions as both a quality-control regulation and a cost-limiting regulation. The nature of an ACO is to align a wide variety of providers: hospitals, primary care physicians, skilled nursing facilities, pharmacies, specialty physicians and surgeons, and others in the effort to manage the health of a population. In short, by aligning—and integrating—the services of all those providers, the ACO could amalgamate so much of the market share that it could run afoul of market-preserving regulations in the form of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act (absent some decisions by federal agencies to relax their interpretations of their own enforcement guidelines) (Kasper 2011).

The Impact of Health Policy on Health Determinants and Health

From government’s perspective, the central purpose of health policy is to enhance health or facilitate its pursuit. Of course, there are multiple perspectives on how to accomplish these purposes, and other purposes may be served through specific health policies, including economic advantages for certain individuals and organizations. While improving the health status of the population is sometimes lost in the smoke of political war, the defining purpose of health policy, as far as government is concerned, is to support the people in their quest for health.

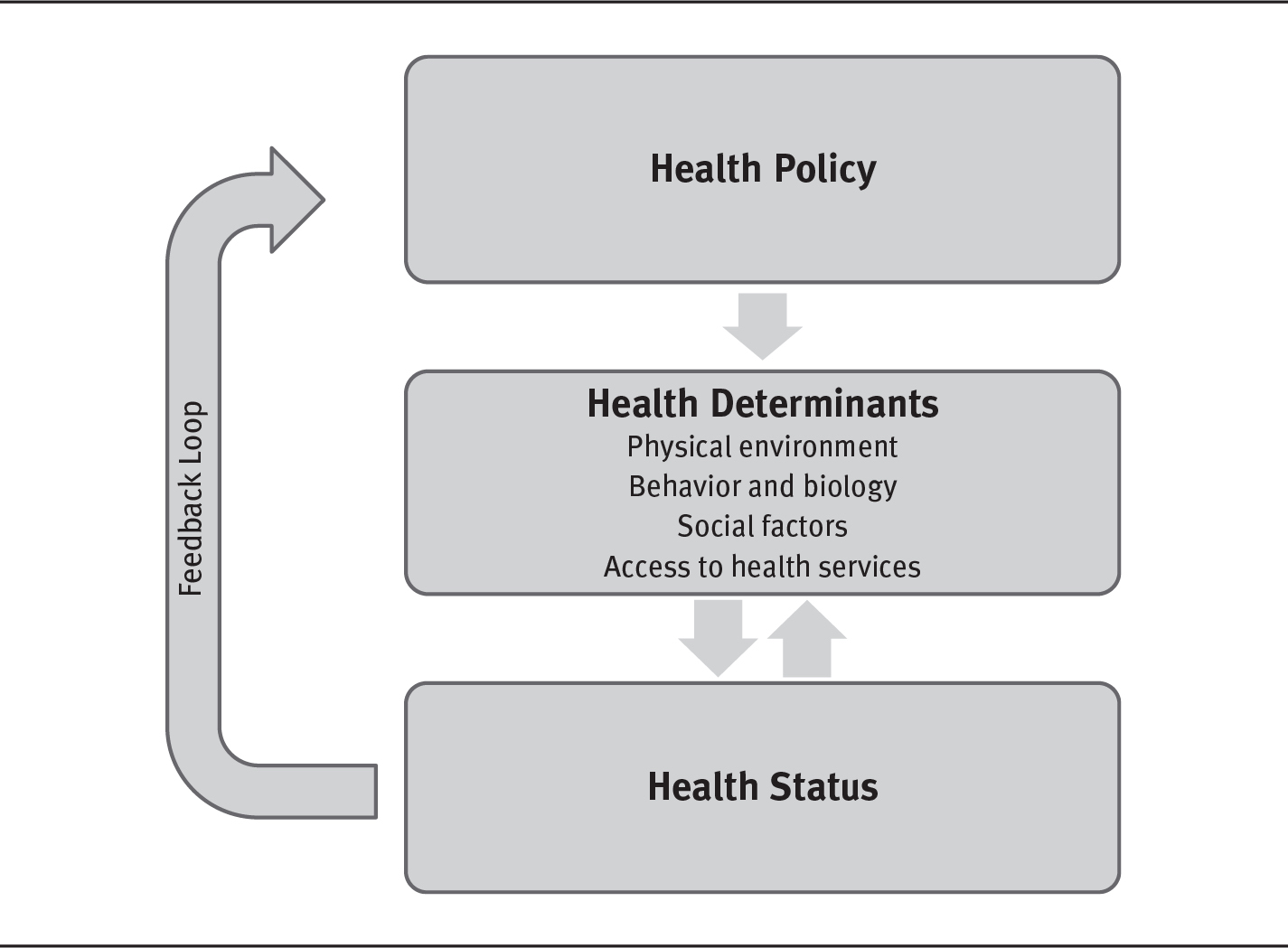

Health policies affect health through health determinants (see exhibit 1.10). Health determinants, in turn, directly affect health. Consider the role of health policy in the following health determinants and, ultimately, its impact on health through them:

- Physical environments in which people live and work

- Behavioral choices and biology

- Social factors, including economic circumstances; socioeconomic position; income distribution in the society; discrimination based on factors such as race or ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation; and the availability of social networks or social support

- Availability of and access to health services

Political bodies monitor a population’s health status and respond when it becomes a significant public—or political—issue. It is no coincidence that Sheppard-Towner passed immediately following women’s suffrage. Motivation arising from constituents’ concerns applies to legislative bodies and administrative agencies alike. Exhibit 1.10 not only displays the synergistic relationship between health determinants and health status but also a feedback loop from health status to health policy. Health status can come to be characterized as a possible problem in the agenda-setting component of our conceptual model of public policymaking, thereby becoming motivation for a policy response.

EXHIBIT 1.10 The Symbiotic Relationship Among Health Policy, Health Determinants, and Health Status

Long Description

The details are as follows:

Health policy leads to health determinant that encompass physical environment, behavior and biology, social factors, and access to health services. The determinants lead to health status that loops back to health policy as feedback.

To summarize, health policies are intended to alter determinants of health to benefit the health status of a given population. Medicare, Medicaid, and the ACA demonstrate this principle. By providing or subsidizing the cost of health insurance, the federal government (and the states with regard to Medicaid) expects to improve access to health services for the elderly, disabled, and the indigent, and for working-class Americans—thereby improving the health status of those populations. Note also that health status and health determinants have a synergistic relationship. Not only do determinants affect one’s health, but the reverse is also true. For example, good health may make it possible to attain a better education or a better job, perhaps one with employer-sponsored insurance. That insurance might improve access to needed care; the education could result in better health literacy. Some examples of how determinants may influence health policy include polluted water and air (physical environment); use and abuse of opioids (behavior); efforts to create safe public places (social factors); and Medicare, Medicaid, and the ACA (access to health services). Note, however, it is not the determinants that impact health policy: it is the resulting effect those determinants have on health status that motivates policymakers to act. While there is legislation intended to modify those determinants to benefit health status, the genesis of the legislation was the amalgamation of factors that provided a problem to be solved through public policy. Note that both regulatory and allocative policies are included in this example.

Health Policies and Physical Environments

When people are exposed to harmful agents, such as asbestos, dioxin, excessive noise, ionizing radiation, or toxic chemical and biological substances, their health is directly affected. Exposure risks pervade the physical environments of many people. Some of the exposure is through such agents as synthetic compounds that are by-products of technological growth and development. Some exposure is through wastes that result from the manufacture, use, and disposal of a vast range of products. Some of the exposure is through naturally occurring agents, such as carcinogenic ultraviolet radiation from the sun or naturally occurring radon gas in the soil.

The hazardous effects of naturally occurring agents are often exacerbated by combination with agents introduced through human activities. For example, before its ban, the widespread use of Freon in air-conditioning systems reduced the protective ozone layer in the earth’s upper atmosphere. As a result, an increased level of ultraviolet radiation from the sun penetrated to the earth’s surface. Similarly, exposure to naturally occurring radon appears to act synergistically with cigarette smoke as a carcinogen.

The health effects of exposure to hazardous agents, whether natural or human made, are well understood. We can examine the impact of health policy on physical environment in the air and in the water. Air, polluted by certain agents, has a direct, measurable effect on such diseases as asthma, emphysema, and lung cancer and aggravates cardiovascular disease. Asbestos, which can still be found in buildings constructed before it was banned, causes pulmonary disease. Lead-based paint, when ingested, causes permanent neurological damage in infants and young children. This paint is still found in older buildings and is especially concentrated in poorer urban communities.

Likewise, hazardous material has found its way into the nation’s water supply. The story of the water supply in Flint, Michigan, provides a frightening reminder of what happens when toxins—in this case lead—leach into a community’s water supply. The entire community, especially children, were at risk for damage to their brains and nervous systems (Ruckart et al. 2019).

Over many decades, government has made efforts to exorcise environmental health hazards through public policies. Examples of federal policies include:

- Clean Air Act (P.L. 88-206)

- Flammable Fabrics Act (P.L. 90-189)

- Occupational Safety and Health Act (P.L. 91-596)

- Consumer Product Safety Act (P.L. 92-573)

- Noise Control Act (P.L. 92-574)

- Safe Drinking Water Act (P.L. 93-523)

Note, however, the swinging political pendulum, which, as we shall see, is a part of the policymaking process; social and economic conditions change, which, in turn, drive political change. Most of the laws referenced here were enacted between 1987 and 1993, an era when protecting the environment had captured public and legislative attention. The winds of change, however, blow constant. The election of 2016 signaled a new era with different priorities, resulting in an administration that has taken several administrative steps to roll back some regulatory changes. One example includes the redefinition of the “Waters of the United States,” which is central to protecting the water under Environmental Protection Agency jurisdiction. The Trump administration in effect narrowed the scope of the definition (Samet, Burke, and Goldstein 2017).

Health policies that mitigate environmental hazards or take advantage of positive environmental conditions are important aspects of any society’s ability to help its members achieve better health. Others believe that the mitigation of environmental hazards has been too costly for businesses—the damage to the environment is minimal, making the trade-off of more robust economic activity beneficial—and that consumers do not share the sense of importance associated with protecting the environment evident in legislation from this domain.

Added to this milieu has been an increasing awareness on the part of the consuming public about both climate change and organic foods. The public has become increasingly aware of agriculture’s impact on the environment. Consumers have organized around concerns about genetically modified organisms, as well as the use of insecticides, herbicides, and antibiotics in the production of food.

These two developments—the move toward less restrictive regulation and the countervailing awareness of climate change and organic, non-GMO foods—are a part of the ongoing political and social debate in the United States. Each side becomes a component part of the larger ebb and flow of social and economic factors that are always a part of life.

Health Policies and Human Behavior and Biology

As Rene Dubos (1959, 110) observed more than a half century ago, “To ward off disease or recover health, men [as well as women and children] as a rule find it easier to depend on the healers than to attempt the more difficult task of living wisely.” The price of this attitude is partially reflected in the major causes of death in the United States. Ranked from highest to lowest, leading causes are heart disease, cancer, unintentional injuries, chronic lower respiratory diseases, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia, kidney disease, and suicide (Murphy, Kochanek, and Arias 2018). Many of these diseases are preventable through improved personal behavior.

Behaviors—including choices about the use of tobacco and alcohol, diet and exercise, illicit drug use, sexual behavior, and gun violence—and genetic predispositions influence many of these causes of death and help explain the pattern. Furthermore, underlying the behavioral factors are such root factors as stress, depression, and feelings of anger, hopelessness, and emptiness, which are exacerbated by economic and social conditions. In short, behaviors are heavily reflected in the diseases that kill and debilitate Americans.

Behavior modification can change the causes of death patterns. The death rate from heart disease, for example, has declined dramatically in recent decades. Although aggressive early treatment has played a role in reducing this rate, better control of several behavioral risk factors—including cigarette smoking, elevated blood pressure, elevated levels of cholesterol, poor diet, lack of exercise, and elevated stress—explains much of the decline. Even with this impressive improvement, however, heart disease remains the most common cause of death and will continue to be a significant cause for the foreseeable future.

Local Policy, Human Behavior, and Biology