The word space internalizes multiple meanings. Confusions arise because different meanings get conflated in inadmissible ways. Sorting out these confusions is essential to the clarification of all manner of substantive issues. Alfred North Whitehead claimed, for example, that “it is hardly more than a pardonable exaggeration to say that the determination of the meaning of nature reduces itself principally to the discussion of the character of time and the character of space.”1 I would likewise claim that many of the key terms we use to characterize the world around us—such as city, state, community, neighborhood, ecosystem and region—cannot properly be understood without a prior consideration of the character of both time and space. It is in this sense that I believe Kant was correct to regard a proper knowledge of geography—in this instance, the proper characterization of space and time—as a necessary precondition as well as the ultimate end-point of all forms of human enquiry.

In what follows, I outline a view of space in relation to time that draws in the first instance upon my own practical work on issues of urbanization and uneven geographical development at a variety of scales (from imperialism to social relations in the city). This view has also been shaped by a partial reading of the long history of philosophical debate on the nature of space and time, as well as by scrutinizing the more recent inquiries of many geographers, anthropologists, sociologists, and literary theorists on the subject.2

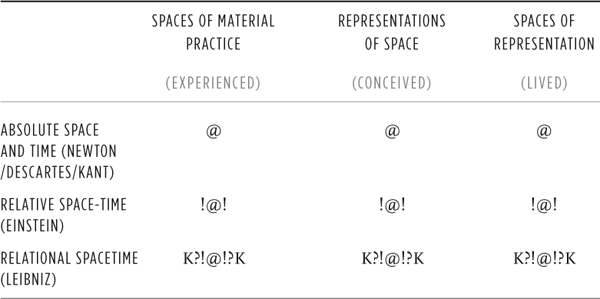

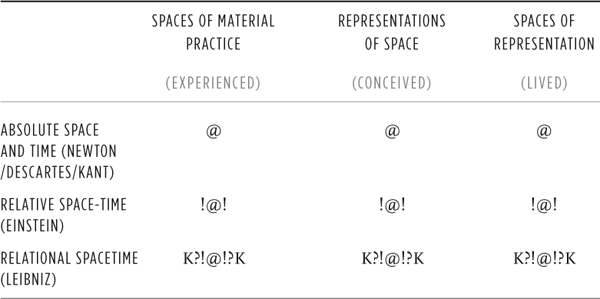

The summary framework to which I appeal operates across two dimensions. On the first, we encounter three distinctive ways of understanding space and time: absolute, relative, and relational. Across the second dimension, we encounter another three definitions (most notably argued for by Lefebvre): space as materially sensed, conceptualized, and lived. I shall go on to argue that space is constituted by the integration of all these definitions. These different ways of understanding space must be kept in dialectical tension with each other if we are to understand how concepts of space and time condition our possibilities, as Kant would put it, to understand the world around us.

The First Dimension

Absolute space is fixed and immovable. This is the space of Newton and Descartes. Space is understood as a preexisting, immovable, continuous, and unchanging framework (most easily visualized as a grid) within which distinctive objects can be clearly identified, and events and processes accurately described. It is initially understood as empty of matter. This is the space to which Euclidian geometry could most easily be adapted. It is amenable to standardized measurement and open to calculation. It is the space of cadastral mapping, Newtonian mechanics, and its derivative engineering practices. It is a primary space of individuation—res extensa, as Descartes put it. Individual persons and things, for example, can clearly be identified in terms of the unique location they occupy in absolute space and time. No other person can be exactly in your or my space at a given time. Location in absolute space and time is, therefore, the means to identify the individuality and uniqueness of persons, things, and processes. Distinctive places, for example, can be identified (named) by their unique location on a map. Within this conception, measurement and calculability thrive. When Descartes’s engineer looked upon the world with a sense of mastery, it was a world of absolute space (and time) from which all uncertainties and ambiguities could in principle be banished and in which human calculation could uninhibitedly flourish. Socially, absolute space is the exclusionary space of private property in land and other bounded entities (such as states, administrative units, city plans, and urban grids). Bounded spaces can be conceptualized as containers of power. Space of this sort is clearly distinguishable from time. Spatial ordering is one thing. Absolute time unfolding on a linear line stretching to an infinite future is another. History, from this perspective, has to be construed as distinct from geography. This was, as we have seen, Kant’s view, so although he departed from Newton in grounding knowledge of space and time in the intuition of the synthetic a priori, he followed the Newtonian separations of space and time in practice.

Relative space is mainly associated with the name of Albert Einstein and the non-Euclidean geometries that began to be constructed most systematically in the nineteenth century.3 This is preeminently the space of processes and motion. Space cannot here be understood separately from time. History and geography cannot be separated. All geography is historical geography, and all history is geographical history. This mandates an important shift of language from absolute space and absolute time to the hyphenated concept of relative space-time. The relative space-time of transportation relations and of commodity and monetary circulation looks and is very different from the absolute spaces of private property. The uniqueness of location and individuation defined by bounded territories in absolute space gives way to a multiplicity of locations that are equidistant from, say, some central city location in terms of time it takes to move to and from that location. Relative identity is multiple rather than singular. Many people can be in the same place relative to me, and I can be in exactly the same place as many other people relative to someone else. We can create completely different maps of relative locations by differentiating between distances measured in terms of cost, time, or modal split (car, bicycle, or skateboard), and we can even disrupt spatial continuities by looking at networks and topological relations (the optimal route for the postman delivering mail, or the airline system operating through key hubs). We know, given the differential frictions of distance encountered on the earth’s surface, that the shortest distance (measured in terms of time, cost, energy expended) between two points is not necessarily given by the way the legendary crow flies. Furthermore, the standpoint of the observer plays a critical role in establishing perspectives. The typical New Yorker’s view of the world, as the famous Steinberg cartoon suggests, fades very fast as one thinks about the lands to the west of the Hudson River or east of Long Island.

All of this relativization does not necessarily reduce or eliminate the capacity for individuation or control, but it does indicate that special rules and laws are required for the particular phenomena and processes under consideration. Measurability and calculability become more complicated. There are multiple geometries from which to choose. The spatial frame varies according to what is relativized and by whom. When Gauss first established the rules of a non-Euclidean spherical geometry to deal with the problems of surveying accurately upon the curved surface of the earth, he also affirmed Euler’s assertion that a perfectly scaled map of any portion of the earth’s surface is impossible. If maps accurately represent directions, then they falsify areas (Greenland looks larger than India on the Mercator map). Each map projection tells its relative truth, even though it is mathematically correct and objective. Einstein took the argument further by pointing out that all forms of measurement depended upon the frame of reference of the observer. The idea of simultaneity in the physical universe, he taught us, has to be abandoned. It was, of course, Einstein’s achievement to come up with exact means to examine such phenomena as the curvature of space when examining temporal processes operating at the speed of light.4

Difficulties do arise, however, as we seek to integrate understandings from different fields into some more unified endeavor. The spatio-temporal frame adequate to represent energy flows within and through ecological systems may not be compatible with that appropriate to represent capital flows through global financial markets. It is hard to put the rapidly changing spatio-temporal rhythms of capital accumulation into the same space-time framework as that required to understand global climate change. Such disjunctions, though difficult to work across, are not necessarily a disadvantage, provided we recognize them for what they are. Comparisons between different spatio-temporal frameworks (as is also the case in the selection of map projection) can illuminate problems of political choice. Do we choose a map projection centered on New York, London, or Sydney, and why is the northern hemisphere always represented as being “on top”? Do we favor a spatio-temporal frame appropriate to follow financial flows or that of the ecological processes they would and frequently do disrupt? When the second Bush administration refused for eight years to deal with global climate change problems because to do so might disrupt the economy, it tacitly evinced a preference for one spatio-temporal framework (the flow of capital as well as the electoral cycle, for example) over another. Relative space-time frameworks are not necessarily stable, either. New technologies of transport and communications have historically and geographically transformed spatio-temporal relations. Relative distances of social interaction and communication between New York, London, and Paris have changed radically over time. Relative locations have shifted, sometimes rapidly, as a result.5

The idea that processes produce their own space and time is fundamental to the relational conception. This idea is most often associated theoretically with the name of Leibniz who, in a famous series of letters to Clarke (effectively a stand-in for Newton), objected vociferously to the absolute view so central to Newton’s theories.6 Leibniz’s primary objection was theological. Newton made it seem as if God were inside a preexisting space and time, rather the maker of space-time through the creation of matter. The absolute view diminished God’s stature. Our contemporary version of this controversy would ask whether the supposed big bang origin of the universe occurred in space and time or whether it was the creation of space-time.

In the relational view, matter and processes do not exist in space-time or even affect it (as in the case of relative space-time). Space and time are internalized within matter and process. Whitehead argued, for example, that “the fundamental order of ideas is first a world of things in relation, then the space whose fundamental entities are defined by means of those relations and whose properties are deduced from the nature of these relations.” It is impossible to disentangle space from time. They fuse into spacetime (the hyphen disappears). Memories and dreams are the stuff of such a fusion. How can we understand things, events, processes in terms of the relational spacetime they produce? Identifications and individuation become problematic, if not seemingly impossible. Relational spacetime implies, furthermore, the idea of internal relations, and this, as B. Ollman has long argued, is fundamental to dialectical modes of analysis.7 An event, process, or thing cannot be understood by appeal to what exists only at some point. It (the event, process, or thing) crystallizes out of a field of flows into what Whitehead calls either “an event” or “a permanence.” But in so doing “it” internalizes everything going on around it within that field of flows, in past, present, and even future. Many individuals assembled in a room to consider political strategies, for example, bring to their discussion within that absolute space a vast array of past experiences, memories, and dreams accumulated directly or indirectly (through reading, for example) from their engagements with the world, as well as a wide array of anticipations and hopes about the future. Under the relational view disparate influences flow from everywhere to everywhere else. These influences can, at least momentarily, congeal to form “monads” (Leibniz’s preferred term), or “events” or “permanences” at identifiable “moments” (in Whitehead’s terms). Identity here means something quite different from the sense we have of it from absolute space or even in relative space-time. It becomes open, fluid, multiple, and indeterminate. Identities become, in short, “immaterial but objective.” But that is how we live day by day.

The implications of this argument are far-reaching. For example, the conception that time (and history) is the domain of masculinity and that space (geography) is the domain of femininity—made much of in some of the feminist literature—rests, as E. Grosz for one openly acknowledges, on accepting the Cartesian view of space and time as both absolute and separable.8 How we understand masculine-feminine relations changes dramatically as we move through the relative to the relational understanding of spacetime. This is so, as Whitehead argues, because the gender power relation precedes the production of spacetime under the relational interpretation. If, therefore, space has indeed become the domain of femininity and history that of masculinity, it would simply be because the gender power relations have made it so. I seriously doubt the utility of this kind of simplistic distinction, however, because the historical geography of gender relations has produced far more nuanced spatio-temporalities than this in almost all social orders that I have encountered or read about. The relational view of spacetime also generates entirely different understandings of the concept of “place” compared to the territorial closures and exclusions that can so easily be manufactured out of absolute conceptions. Edward Casey, as we shall see in chapter 8, rests his whole argument for the priority of “place” over “space” on a profound objection to the emptiness of space presupposed in the Cartesian/Kantian absolute view.9 His objections dissolve when confronted with relational interpretations. And if, as Whitehead maintains, all conceptions of nature arise out of our understandings of space and time, then our whole understanding of the socio-ecological dialectic, as well as our understanding of place, is directly implicated in how we formulate our understandings of space and time.

What can this possibly mean for everyday understandings and practices? Consider a few examples where the relational conception makes intuitive sense. If we ask, along with Whitehead, what is the time and space of a thought or a memory, then we are hard pressed to find a material answer. We cannot find thoughts or memories by dissecting someone’s brain. They seem to fly around in our heads without themselves taking material form, although an active brain obviously exists as a material enabling structure that supports the processes of thinking and memorizing. But if the thoughts and memories are themselves immaterial, fluid, and unstable, they can and often do have solid material and hence objective consequences when they animate action.

In relational spacetime, direct measurement is problematic, if not impossible. But why should we believe that spacetime only exists if it is quantifiable and measurable? Dreams and memories cannot be dismissed as irrelevant because we cannot quantify and measure their spacetime. The inability of positivism, empiricism, and traditional materialism to evolve adequate understandings of spatial and temporal concepts beyond those that can be measured has long been a serious limitation on thinking through the role of spacetime. Relational conceptions bring us to the point where mathematics, poetry, and music merge, where dreams, daydreams, memories, and fantasies flourish. That, from a scientific (as opposed to aesthetic) viewpoint, is anathema to those of a narrow positivist or simple materialist bent. The problem is to find adequate representations for the immaterial spatio-temporality of, say, social and power relations. Kant, as we have seen, recognized the dilemma in a shadowy form. Though absolute space was characterized as real and independent of matter in the Newtonian scheme of things, there was no way to come up with an independent material measure of it outside of the matter and the processes it contained. Kant here tried to build a bridge between Newton and Leibniz by incorporating the concept of space within the theory of aesthetic judgment and the synthetic a priori. In so doing, Kant encountered some horrendously difficult contradictions.10 Kant clearly failed to recognize the potential power of Leibniz’s relational conception. Leibniz’s return to popularity and significance, not only as the guru of cyberspace but also as a foundational thinker with respect to more dialectical approaches to mind-brain issues and quantum theoretical formulations, signals a return toward relational views. Many contemporary thinkers go beyond absolute and relative concepts and their more easily measurable qualities, as well as beyond the Kantian compromise. But the relational terrain is a challenging and difficult terrain to cultivate successfully. Einstein, for one, could never accept it and so denied quantum theory until the end. Alfred North Whitehead did much to advance the relational view in science.11 David Bohm’s explorations of quantum theory also focus heavily on relational thinking. G. Deleuze made much of these ideas in reflections on baroque architecture and the mathematics of the fold, drawing inspiration from Leibniz and Spinoza.12 Together with Guattari, Deleuze charted some very interesting relational paths of analysis in texts like A Thousand Plateaus. Relational conceptions have recently entered into the political arena, particularly through the work of Arne Naess on deep ecology and through T. Negri’s recent writings on empire and the multitude; both of these authors, it should be noted, draw heavily upon the relational thinking of Spinoza rather than upon Leibniz. 13 And A. Badiou’s theorization of “the event” as fundamental to our understandings has led him to a particular kind of political critique.14

But why and how would I, as a working geographer, find the relational mode of approaching spacetime useful? The answer is quite simply that there are certain topics, such as the political role of collective memories in urban processes, that can be approached only in this way. I cannot box collective memories in some absolute space (clearly situate them on a grid or a map), nor can I understand their circulation according to the rules, however sophisticated, of circulation and diffusion of ideas in relative space-time. I cannot understand much of what Walter Benjamin does in his Arcades project without appealing to relational ideas about the spacetime of memory. I cannot even understand the idea of the city without situating it in relational terms. If, furthermore, I ask the question, of what the Basilica of Sacré Coeur in Paris, Tiananmen Square in Beijing, or “Ground Zero” in Manhattan means, then I cannot come to a full answer without invoking relationalities. 15 And that entails coming to terms with the things, events, processes, and socio-ecological relations that have produced those places in spacetime.

So is space (space-time and spacetime) absolute, relative, or relational? I simply don’t know whether there is an ontological answer to that question. In my own work I think of it as all three. I reached that conclusion thirty years ago and I have found no particular reason (nor heard any arguments) to make me change my mind. This is what I then wrote:

space is neither absolute, relative or relational in itself, but it can become one or all simultaneously depending on the circumstances. The problem of the proper conceptualization of space is resolved through human practice with respect to it. In other words, there are no philosophical answers to philosophical questions that arise over the nature of space—the answers lie in human practice. The question “what is space?” is therefore replaced by the question “how is it that different human practices create and make use of different conceptualizations of space?” The property relationship, for example, creates absolute spaces within which monopoly control can operate. The movement of people, goods, services, and information takes place in a relative space because it takes money, time, energy, and the like to overcome the friction of distance. Parcels of land also capture benefits because they contain relationships with other parcels . . . in the form of rent relational space comes into its own as an important aspect of human social practice.16

Are there rules for deciding when and where one spatial frame is preferable to another? Or is the choice arbitrary, subject to the whims of human practice? The decision to use one or other conception certainly depends on the nature of the phenomena under investigation or the political objective in mind. The absolute conception may be perfectly adequate for determining narrow issues of property boundaries and border determinations for a state apparatus (indeed, it was no accident that the absolute view came into prominence, if not dominance, around the time the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648 set up the system of European sovereign states), but it helps me not a whit with the question of what is Tiananmen Square, Ground Zero, or the Basilica of Sacré Coeur. Conversely, state apparatuses obsessed with identities, control, and surveillance turn again and again to the absolute conceptions of space and time as central to their mission of effective governance and control, thereby imposing absolute conceptions on much that is or could be either relative or relational. I therefore find it helpful—if only as an internal check—to sketch in justifications for the choice of an absolute, relative, or relational frame of reference. Furthermore, I have sometimes presumed in my practices that there is some hierarchy at work: that relational space can embrace the relative and the absolute, relative space can embrace the absolute, but absolute space is just absolute and that is that. But I do not recommend this view as a working principle, let alone try to defend it theoretically. I find it far more interesting in principle to keep the three concepts in dialectical tension with each other and to constantly think through the interplay among them. Ground Zero is an absolute space at the same time as it is located in relative space-time and has relational positionalities.

From this I derive the first preliminary determination: the three conceptions of absolute, relative, and relational need to be held in dialectical tension with each other if we are to understand space as a condition of possibility of all other forms of knowing.

The Second (Lefebvrian) Dimension

H. Lefebvre constructs a quite different way of understanding spatiality in terms of human practices. He derives (almost certainly drawing upon Cassirer’s distinctions among organic, perceptual, and symbolic spaces, though, as is often the case in French intellectual circles, without acknowledgment) a tripartite division of material space (space as experienced through our sense perceptions), the representation of space (space as conceived), and spaces of representation (space as lived). The second set of terms (those placed within parentheses) are not identical to the first, but in what follows I shall largely ignore that problem. I will pay most attention to the bracketed meanings, since these refer concretely to human behavior and social practices.17

Material space is, for us humans, the world of our sense perceptions, as these arise out of the material circumstances of our lives: for this reason it can be called the perceptual space of primary experience mediated through human practices. We touch things and processes, feel them, see them, smell them, hear them, and infer the nature of space from those experiences. How we represent this world of experienced sense perceptions is, however, an entirely different matter. We use abstract representations (words, graphs, maps, diagrams, pictures, geometry, and other mathematical formulations) to represent space as we perceive it. In so doing we deploy concepts, codes, and abstractions. The correspondence between the material space of sense perceptions and its representation is always open to question and frequently fraught with dangerous illusions. But Lefebvre, along with other Marxists like W. Benjamin, insists that we also have imaginations, fears, emotions, psychologies, fantasies, and dreams. What Lefebvre calls, rather awkwardly, spaces of representation refers to the way we humans live—physically, affectively, and emotionally—in and through the spaces we encounter. Venturing down a dark street at night we may feel either fearful or adventurous. One person may welcome open space as a terrain of liberty while another, a victim of agoraphobia, may feel so insecure as to experience a panic attack. Some people welcome open borders for immigrants, while others want to keep them tightly shut for security reasons. A geographer like Yi-fu Tuan has focused much of his work on cultural and personal divergences in how space is lived.18

The way we live in space cannot be predicted from material stimuli and sense perceptions or even from its manner of representation. But this does not mean that the three dimensions are disconnected. Lefebvre keeps them in a dialectical tension. Mutual and reciprocal influences flow freely between them. The way a space is represented and conceptualized, for example, may affect (though not in easily predictable ways) how the space is lived in and even materially sensed. If I have just read a horror story or Freud, then my feelings about venturing down that dark corridor-like street will surely be affected. Furthermore, my physical experience may be heightened (my senses may be “on edge,” as we say) precisely because I am living in that space in a particular state of fear or anticipation. Conversely, the strange spatio-temporality of a dream, a fantasy, a hidden longing, or a lost memory, or even a peculiar thrill or tingle of fear as I walk down a street, may lead me to seek out conceptualizations and representations that can convey something of what I have lived to others. The artist Edvard Münch may have had a nightmare of some sort. Passing through a series of conceptualizations and codes of representation, he produced a material object, the painting called The Scream, open to the material sense experience of others. We look at this thing—the painting—and get some feeling of what it might have been like to live that moment in that way. The physical and material experience of looking at the spatial ordering of the painting is mediated by representations in such a way as to help us understand the immateriality of a state of mind. I suspect that the continuing fascination with Velázquez’s painting called Las Meniñas (a fascination that led Picasso to undertake endless variations on its themes and Foucault to use it as a foundational starting point for reflection in The Order of Things) is due to the way its spatial ordering within the absolute space of the pictorial frame conveys some sense of the shifting sands of changing social power relations in that place and time. This is certainly the manner in which T. J. Clark interprets the rising tide of hostile responses to Courbet’s famous painting Burial at Ornans as it progressed from the provinces toward Paris where the rentier landed class were all too familiar with and fearful of the nature of the class relations it portrayed.19

The spaces and times of representation that envelop and surround us as we go about our daily lives likewise affect both our direct sensory experiences and the way we interpret and understand representations. We may not even notice the material qualities of spatial orderings incorporated into daily life because we adhere to unexamined routines. Yet through those daily material routines of everyday life we absorb a certain sense of how spatial representations work and build up certain spaces of representation for ourselves (such as the visceral sense of security in a familiar neighborhood or the sense of being “at home”). We only notice when something appears radically out of place. It is the dialectical relation between the categories that really counts, even though it is useful for purposes of understanding to crystallize each element out as a distinctive moment to the experience of space and time.

Many contemporary artists, making use of multimedia and kinetic techniques, create experiential spaces in which several modes of experiencing space-time combine. Here, for example, is how Judith Barry’s contribution to the Third Berlin Biennial for Contemporary Art is described in the catalogue:

In her experimental works, video artist Judith Barry investigates the use, construction and complex interaction of private and public spaces, media, society, and genders. The themes of her installations and theoretical writings position themselves in a field of observation that addresses historical memory, mass communication, and perception. In a realm between the viewer’s imagination and media-generated architecture, she creates imaginary spaces, alienated depictions of profane reality. . . . In the work Voice Off . . . the viewer penetrates the claustrophobic crampedness of the exhibition space, goes deeper into the work, and, forced to move through the installation, experiences not only cinematic but also cinemaesthetic impressions. The divided projection space offers the possibility of making contact with different voices. The use and hearing of voices as a driving force, and the intensity of the psychic tension—especially on the male side of the projection,—conveys the inherent strength of this intangible and ephemeral object. The voices demonstrate for spectators how one can change through them, how one tries to take control of them and the loss one feels when they are no longer heard.

Barry, the catalogue concludes, “stages aesthetic spaces of transit that leave the ambivalence between seduction and reflection unresolved.”20

From this description we see how we need to take our understanding of space and time to an even deeper level. There is much here that refers back to the distinctions between absolute space and time (the cramped physical structure of the exhibit), relative space-time (the sequential motion of the visitor through the space), and relational spacetime (the memories, the voices, the psychic tension, the intangibility and ephemerality, as well as the claustrophobia). Yet we cannot let go of the Lefebvrian categories either. The constructed spaces have material and sensual, conceptual and lived dimensions.

A Structural Representation

Reflection on the description of Barry’s work leads me to take a speculative leap in how best to construe the multidimensionality of space and time. Consider, then, how matters look when we put the threefold division of absolute, relative, and relational space-time (spacetime) in direct relation to the tripartite division of sensed, conceptualized, and lived. The result is a three-by-three matrix (fig. 1). The points of intersection within the matrix suggest different modalities of understanding the meanings of space, space-time, and spacetime. Unfortunately, a matrix mode of representation is restrictive because it depicts an absolute space only. Since I am also resorting to a representational practice (conceptualization), I cannot do justice to space as materially sensed or lived, either. The matrix therefore has limited revelatory power. If it is treated as a fixed classification that constitutes all there is, then my project will come to naught. I find it helpful, however, to consider the combinations that arise at different intersections within the matrix as a way to jump-start the analysis. Reading across or down the matrix yields complex combinations of meanings. Confining oneself to just one modality of thinking becomes impossible. Actions in absolute space end up making sense only in relational terms, for example. The rigidities of the matrix can be surpassed only by placing all the categories and their combinations in dialectical tension. Let me illustrate.

FIGURE 1

In what space or spacetime is the site known as “Ground Zero” in Manhattan located, and how does this affect our understanding of that site and of what should be built there? It is, plainly, an absolute physical space, and someone holds the property rights to it. It stands to be materially reconstructed as a distinctive thing. There is much discussion about retaining walls and load-bearing capacities. Engineering calculations (informed by Newtonian mechanics) and competing architectural designs (representations) are submitted. Aesthetic judgments on how the space, once turned into a material artifact of some sort, might be lived in by those who visit it or work there are also influential considerations. Only after it is built will we get some sense of how people might live in that space. The problem is to so arrange the physical space as to produce an emotive affect while matching certain expectations (commercial as well as emotive and aesthetic) as to how the space might be experienced. Once constructed, the experience of the space may be mediated by representational forms (such as guide books, museums, and plans) that help us interpret the intended meanings of the reconstructed site. But moving dialectically across the dimension of absolute space alone is much less rewarding than the insights that come from appealing to the other spatio-temporal frames. Capitalist developers are keenly aware of the relative location of the site and judge its prospects for commercial development according to a logic of exchange relations and the flows of people, commodities, and capital that relate to it and give the site its potential commercial and speculative value. Its centrality and proximity to the command and control functions of Wall Street are important attributes, and if transportation access can be improved in the course of reconstruction, then so much the better, since this can only add to future land and property values. For the developers, the site does not merely exist in relative space-time: the re-engineering of the site offers the prospect of transforming relative space-time so as to enhance the commercial value of the absolute spaces (by improving access to airports, for example). The temporal horizon is then dominated by considerations of the amortization rate and the interest/discount rate applying to fixed capital investments in the built environment.

But there would almost certainly be popular objections, led by the families of those killed at that site, to thinking and building only in these absolute or relative space-time terms. Whatever is built at this site has to say something about individual and collective memory. Memory is immaterial but objective and hence relational. There will likely also be pressures to say something about the meanings of community and nation, as well as about future possibilities (perhaps even a prospect of eternal truths). Nor could the site ignore the issue of relational spatial connectivity to the rest of the world. Can something experienced as a local and personal tragedy be reconciled with an understanding of the international forces that were so powerfully condensed within those few shattering moments in a particular place? Will we get to feel in that space the widespread resentment in the rest of the world toward the way U.S. hegemony was so selfishly being exercised throughout the 1980s and 1990s? Will we get to know that the Reagan administration played a key role in creating and supporting the Taliban in Afghanistan in order to undermine the Soviet occupation and that Osama bin-Laden turned from being an ally of the United States into an enemy because of U.S. support for the corrupt regime in Saudi Arabia? Or will we only learn of cowardly, alien, and evil “others” out there who hated the United States and sought to destroy it because of all it stood for in terms of liberty and freedom? The relational spatio-temporality of the event and the site can be exhumed with enough dedicated digging. But the manner of its representation and of its materialization is uncertain. The outcome will clearly depend upon political struggle. And the fiercest battles will have to be fought over what relational spacetime the rebuilding will invoke, what it will project as a symbol to the world. Governor Pataki, for example, in canceling the plans for a Freedom Museum there on the grounds that at some time in the future an exhibit critical of U.S. policies might be mounted, mandated that nothing should be placed at the site that could ever be offensive to the memory of those who died there. His intent was to refuse any and all expression of criticism of U.S. military and financial engagements with the world. Capitalist developers would not be averse to combining their mundane commercial concerns with inspiring symbolic statements (emphasizing the power and indestructibility of the political-economic system of global capitalism that received such a body blow on September 11, 2001) by erecting, say, a towering phallic symbol that spells defiance. They seek their own distinctive expressive power in relational spacetime. But there are all manner of other relationalities to be explored. What will we know about those who attacked, and how far will we connect? The site is and will have a relational presence in the world, no matter what is built there, and it is important to reflect on how this “presencing” works: will it be lived as a symbol of U.S. arrogance or as a sign of global compassion, reconciliation, and understanding? Taking up such matters requires that we embrace a relational conception of what the absolute space of Ground Zero is all about. And that, it turns out, is where the most interesting and contested meanings lie.

The Space and Time of Marxian Theory

This general framework provides a beginning point for the integration of concepts of space and time into all segments of literary and social theory. Let me illustrate how it works in relation to Marxian theory in particular. Marx is a relational thinker. In revolutionary situations, such as that of 1848, he worried, for example, that the past as memory might weigh like a nightmare on the brain of the living. He went on to pose the key political question: how might a revolutionary poetry of the future be constructed in the then and there?21 He also pleaded with Cabet not to take his communist-minded followers to the New World. There, Marx averred, the Icarians would only replant the attitudes and beliefs internalized from the experience of the old. They should, Marx advised, stay as good communists in Europe and fight for a revolutionary transformation in that space, even though there was always the danger that a revolution made in “our little corner of the world” would fall victim to the global forces ranged around it.22

In the works of Marxists like E. P. Thompson, R. Williams, and others, we find different levels of appreciation of spatio-temporality.23 In Williams’s novel People of the Black Mountains, for example, the relationality of spacetime is central. Williams uses it to bind the narrative together, directly emphasizing the different ways of knowing that come with different senses of spacetime: “If lives and places were being seriously sought, a powerful attachment to lives and to places was entirely demanded. The polystyrene model and its textual and theoretical equivalents remained different from the substance they reconstructed and simulated. . . . At his books and maps in the library, or in the house in the valley, there was a common history which could be translated anywhere, in a community of evidence and rational enquiry. Yet he had only to move on the mountains for a different kind of mind to assert itself; stubbornly native and local, yet reaching beyond to a wider common flow, where touch and breadth replaced record and analysis; not history as narrative but stories as lives.” 24

For Williams the relationality comes alive when walking on the mountains. It centers a completely different sensibility and feeling than that constructed from the archive. While it is stubbornly local, it reaches beyond to a wider common flow and thereby bridges the gap between geography and locality, on the one hand, and cosmopolitan concerns and some sense of our species being, on the other. These were exactly the sentiments of Elisée Reclus, a famous nineteenth-century anarchist geographer.25 Interestingly, it is only in his novels that Williams seems able to get at this problem. How then can the broader perspectives I have outlined on the dialectics of space and spacetime become more closely integrated into our reading, interpretation, and use of Marxian theory? Let me lay aside all concern for caveats and nuances in order to present an argument in the starkest possible terms.

In the first chapter of Capital, Marx introduces three key concepts of use value, exchange value, and value. Everything that pertains to use value lies in the province of absolute space and time. Individual workers, machines, commodities, factories, roads, houses, actual labor processes, expenditures of energy, and the like can all be individuated, described, and understood in themselves within the Newtonian frame of absolute space and time. This is the domain of physical calculability and rational mathematical modeling of production systems, input-output structures, and systematic planning. Everything that pertains to exchange value lies, in the first instance, in relative space-time because exchange entails movements of commodities, money, capital, labor power, and people over time and space. It is the circulation, the perpetual motion, that counts. Exchange, as Marx observes, therefore breaks through all barriers of (absolute) space and time.26 It perpetually reshapes the geographical and temporal coordinates within which we live our daily lives. It gives different meaning to the use values we command in absolute space. With the advent of money, this “breaking through” defines an even grander and more fluid universe of exchange relations across the relative space-time of the world market (understood not as a thing but as continuous movement and interaction). The circulation and accumulation of capital occurs, in short, in the first instance in a relative space-time that is itself perpetually subject to change through the ability to move in space-time. But this is the world of a posteriori valuations, of speculative ventures, and the anarchy of market coordinations.

Value is, however, a relational concept. Its referent is, therefore, relational spacetime. Value, Marx states (somewhat surprisingly), is immaterial but objective. “Not an atom of matter enters into the objectivity of commodities as values.”27 As a consequence, value does not “stalk about with a label describing what it is,” but hides its relationality within the fetishism of commodities. The only way we can approach it is through that peculiar world in which material relations are established between people (we relate to each other through what we produce and trade) and social relations are constructed between things (prices are set for what we produce and trade). Values are, in short, social relations, and these are always immaterial but objective. They are impossible to measure except by way of their effects (try measuring any social relation of power directly, and you always fail). Value, according to Marx, internalizes the whole historical geography of innumerable labor processes set up in the world market. Many are surprised to find that Marx’s most fundamental concept is “immaterial but objective,” given the way he is usually depicted as a materialist for whom anything immaterial would be anathema. But he roundly condemns the materialism of those scientists who cannot incorporate history (and, I would add, geography) into their understandings. This relational definition of value renders moot if not misplaced all those attempts to come up with some direct and essentialist measure of it. I repeat: social relations can only ever be measured by their effects. Yet, value can be represented both in the relative space-time of exchange and the absolute space and time of use values. This is what money does.

If my characterization of the Marxian categories is correct, then this shows no priority can be accorded to any one spatio-temporal frame. The three spatio-temporal frames must be kept in dialectical tension with each other in exactly the same way that use value, exchange value, and value dialectically intertwine within the Marxian theory. There would, for example, be no value in relational spacetime without myriad concrete labors constructed in absolute spaces and times (for example, in the factory during the working day). Nor would value emerge as an immaterial but objective power without the innumerable acts of exchange, the continuous circulation processes, that weld together the global market in relative space-time. Value is, then, a social relation that internalizes the whole history and geography of concrete labors in the world market. It is expressive of the social (primarily but not exclusively class) relations of capitalism constructed on the world stage. It is crucial to mark the temporality involved, not only because of the significance of past “dead” labor (fixed capital, including that embedded in built environments), but also because of all the traces of the history of proletarianization, of primitive accumulation, of technological developments that are internalized within the value form. Above all, we have to acknowledge the “historical and moral elements” that always enter into the determination of the value of the commodity labor power.28 We then see Marx’s theory working in a particular way. The spinner and weaver embed value (that is, abstract labor as a relational determination that has no material measure) in the cloth by performing concrete labor in an absolute space and time. The objective power of the value relation is registered when they are forced to give up making the cloth and the factory falls silent because conditions in the world market are such as to make this activity in that particular absolute space and time valueless. While all this may seem obvious, the failure to acknowledge the interplay among the different spatio-temporal frames in Marxian theory often produces conceptual confusion. Much discussion of so-called “global-local relations” has become a conceptual muddle, for example, because of the inability to understand the different spatio-temporalities involved.29 We cannot say that the value relation causes the factory to close down, as if it is some external abstract force. It is the changing concrete conditions of labor in the absolute spaces of Chinese factories that, when mediated through exchange processes in relative space-time across the world market, transform value as an abstract social relation in such a way as to bring a concrete labor process in the Mexican factory to closure. A popular term like globalization functions relationally in exactly this way, even as it disguises the value form and its reference to class relations. If we ask: “where is globalization?” we can give no immediate material answer.

We can see this dialectic at work in Marx’s understanding of how money comes to represent value. A particular use value—gold—is produced in a particular way in a particular place and time. Through exchange in relative space-time that particular commodity, by virtue of its qualities of consistency and permanence, begins to take on the role of a money commodity (other commodities, such as silver, copper, or cowrie shells could do the job equally well). Its use value is that it stay permanently in circulation within the relative space-time sphere of exchange value. To function more effectively as a means to circulate commodities, relational symbols of money (coins, paper money, and monies of account) are constructed. Money becomes a relational form that nevertheless retains its position in relative space-time as well as in absolute space and time (the coin I have in my pocket). But its presence in these three spheres centers a whole series of contradictions between the universal and the local, the symbolic and the tangible, the functional and the transcendental. Marx analyzed these contradictions in a particular place and time, but we still live these contradictions today, though in very different ways. How do we understand the symbolic forms of global money on the world market (the symbols that cover the financial pages of our newspapers) in relation to the coins we carry in our pockets? In what ways are the contradictions that Marx warned us might be the source of financial and monetary crises still with us, indeed, even more emphatically so now than when Marx wrote?

So far, I have largely confined attention to a dialectical reading of Marxian theory down the lefthand column of the matrix. What happens when I start to read across the matrix, instead? The materiality of use values and concrete labors in the factory is obvious enough when we examine the laborer’s social practices and sensory experiences in absolute space and time. But how should this be represented and conceived? Physical descriptions are easy to produce, but the social relations (themselves not directly visible or measurable) under which the work is performed are critical also. Within capitalism the wage laborer can be conceptualized (second column) as a producer of surplus value for the capitalist, and this can be represented as a relation of exploitation. This implies that the labor process is lived (third column) as alienation. Alienated subjects are likely to be, the argument goes, revolutionary subjects. Under different social relations—for example, those of socialism or anarchism—work could be lived as creative satisfaction and conceptualized as self-realization through collective endeavors. It may not even have to change materially in order to be reconceptualized and lived in a quite different way. This was, after all, Lenin’s hope when he advocated the adoption of Fordism in Soviet factories. Fourier, for his part, thought that work should be about play and the expression of desire and should be lived as sublime joy; for that to happen, he believed, the material qualities of work processes would need to be radically restructured.

At this point we have to acknowledge a variety of competing possibilities. In his book Manufacturing Consent, for example, M. Burawoy found that the workers in the factory he studied did not generally experience work as alienation.30 This arose because they smothered the idea of exploitation by turning the workplace into a site for role- and game-playing (Fourier-style) The labor process was performed by the workers in such a way as to permit them to live the process in a nonalienated way. There are obvious advantages for capital in this, since unalienated workers often work more efficiently and are unlikely to act as revolutionary subjects. And, we have to admit, if there is no prospect of any radical revolutionary change, workers might just as well try to live their lives in an unalienated way and have as much fun as they can while they are about it. Capitalists have sometimes promoted measures, such as calisthenics, quality circles, and the like, to try to reduce alienation and to emphasize incorporation (the Japanese were particularly notable for this). They have also produced alternative conceptualizations that emphasize the rewards of hard work and produce ideologies to negate the theory of exploitation. While the Marxian theory of exploitation may be formally correct, therefore, it does not always or necessarily translate into alienation and revolution. Much depends on how the labor process is conceptualized. Part of class struggle is about driving home the significance of exploitation as the proper conceptualization of how concrete labors are accomplished under capitalist social relations. Again, it is the dialectical tension among the material, the conceived, and the lived that really matters. If we treat the tensions in a mechanical way, then we are lost.

Now let me range widely (and perhaps wildly) across the whole matrix to see what can be gained when we think dialectically across its various combinations. Consider, for example, a category such as class consciousness. In what space and time can it be found, and how can it be articulated across the spatio-temporal matrix in ways that lead to fruitful results? Let me suggest in the first instance that it resides primarily in the conceptualized relational space of Marxian theory, that it must therefore be regarded as immaterial and universal. But for that conception to have meaning it must be both relationally lived (be part of our emotive and affective being in the world) at the same time as it operates as an objective force for change in particular (that is, absolute) spaces and times. In order for this to be so, workers have to internalize class consciousness in their lived being and find ways to put that sense of what ought to be into motion across relative space-time. But only when the presence of a class movement is registered in the absolute space and time of streets, factories, corporate headquarters, and the like can the movement register a direct materiality. This even applies at the level of protest. No one really understood what the antiglobalization movement stood for until bodies appeared on the streets of Seattle at a certain time.

But who can say what workers’ dreams and beliefs are actually about? Rancière, for example, provides a good deal of substantive evidence that workers’ dreams, and hence aspirations, in the 1830s and 1840s in France were far from what many Marxist labor historians have inferred from a study of their material circumstances.31 They longed, he says, for respect and dignity, for partnership with capital, not its revolutionary overthrow. We can, of course, dispute Rancière’s findings, but the world of utopian dreams is a complicated world, and we cannot make automatic presumptions as to how it may be constituted. But we can say with certainty that only when those dreams are converted into an active force do these immaterial longings and desires take on objective powers. And for that to happen requires a dialectical movement across and through the whole matrix of spatio-temporal positionings. Blockages can be thrown up at any point. Hegemonic neoliberal representations of market exchange as both efficient and just create barriers to reconstructions of actual labor processes, because that conception of the market, if accepted, leads people to live their lives as if anything and everything wrong is their own individual responsibility and as if the only answer to any problem lies in strengthening existing or developing new markets (such as in pollution credits). Transformations in spatial and temporal relations through technological innovations alter identities and political subjectivities at the same time as they shift terrains across which the circulation of capital and labor can occur. Time horizons of capital circulation shift with the discount rate, which is in turn sensitive to the circulation of speculative capital in financial markets. The effects are registered in the absolute spaces of neighborhoods (as in the dramatic neighborhood concentrations of foreclosures, largely in African American areas, in U.S. cities during the sub-prime mortgage crisis of 2007), factories, shopping malls, and entertainment centers. But to accept the market logic is to interpret what happens as both inevitable and just, precisely because the market is predominantly (though erroneously) conceptualized as the harbinger and guardian of individual freedoms.

Dynamics

Any absolute form of spatial representation, such as a matrix, has inherent limits. At the heart of Leibniz’s relational conception lies the idea that matter and process define space and time. This poses the question: what are the processes at work within the matrix itself? If there are multiple processes, can there be multiple spatio-temporal worlds and multiple matrices? While Leibniz appealed to dreams and fairy stories to demonstrate the possible existence of many spacetime worlds, he considered that God in His wisdom had chosen in practice only one: spacetimes were harmonized with each other by God’s embrace of “the principle of sufficient reason.” Whitehead, eschewing theology, conceded the possibility that different processes might produce different spacetimes but held that differences were fortunately small. Different spacetimes became “cogredient” (interwoven and consistent) with each other, at least in the physical world. This presumption cannot be (fortunately or unfortunately) sustained in the realm of social practices. Harmony and cogredience here give way to antagonism, opposition, conflict, and contradiction. Capitalism’s spacetime is not at all consistent or cogredient with the spacetime of ancient cosmologies or even that of human reproduction (as illustrated, for example, in Harevens’s compelling description of the contrast between industrial and family times in the twentieth-century United States). We therefore have to concede, in the first instance, a chaos of different spatio-temporalities attaching to different processes and the very real possibility of huge breaks and disjunctions between them. On this point the anthropological, geographical, and historical evidence is conclusive. The spacetime worlds of the medieval monk, the Nuer, the Ashanti, the Salteaux Indians, the inhabitants of Gawa, and the Wall Street financier are radically different from each other.32 The spacetime worlds of the homeless, the welfare recipients, the day laborers, the schoolteachers, and the financiers in New York City likewise differ, as is indeed also the case with Mexican, Haitian, Bangladeshi, Korean, and Filipino immigrants living in the same city. The Wall Street financier may operate in one spacetime at work and in another when he goes home and thinks of how soon he might retire and go fishing. His trophy wife will construct a quite different spacetime world and, not being enamored of fishing, will doubtless ultimately demand alimony to live in it. Corporate capital may insist upon a rate of exploitation of a renewable resource (such as a fish population) in ways so inconsistent with the rate of its reproduction that the resource is destroyed.

How, then, are we to make sense of the innumerable and seemingly inconsistent spatio-temporalities that coexist within our social world? There are two answers to this question. The first says we simply cannot arbitrarily impose order upon this chaos and that the chaos is part of the ferment out of which new configurations of social life are perpetually being constructed. This is the picture that seemingly emerges, for example, in D. Moore’s examination of intersecting spatio-temporalities in the Kaerezi district of Zimbabwe, where “situated struggles produced an entangled landscape in which multiple spatialities, temporalities and power relations combine: rainmaking and chiefly rule; colonial ranch and postcolonial settlements scheme; site-specific land claims and discourses of national liberation; ancestral inheritance and racialized dispossession. Entanglement suggests knots, gnarls and adhesions rather than smooth surfaces; an inextricable interweave that ensnares; a compromising relationship that challenges while making withdrawal difficult if not impossible.”33

The second view says that while there is plenty of chaos and contradiction, social life in a particular social formation ultimately becomes so ordered as to render one particular configuration of spatio-temporality both dominant (socially imposed as a disciplinary apparatus) and hegemonic (internalized within our very being, often without our realizing it). Different spatio-temporalities, within a particular social formation, tend, therefore, to become cogredient—interwoven and interconnected with each other—in the ways that Whitehead envisages. But not totally so. Resistance and dissent within a social formation may be registered as a longing and desire (sometimes converted into an active struggle) to construct and adhere to some alternative spatio-temporality: the ecological movement is often particularly explicit on this point as it seeks to hold back the spatio-temporalities of capital accumulation in the name of preserving ecological processes (for example, the reproduction of habitats and ecological assemblages of a certain sort). In Moore’s account a certain cogredience emerges through an exploration of how “localized land rights became articulated through relational histories of nation, regional anticolonial movements, the legacies of imperial projects in southern Africa, and globalized discourses of development, human rights, and social justice.” While held together in the net of governmentality, political economic processes, and racialized dispossession, the different forms of spatio-temporality provide resources with which to contest a dominant social order.

I broadly adhere to this second view. But to advance the argument, we must first understand how it was that capitalism’s distinctive spacetime (itself dynamic and by no means fixed and static) came for the most part to be accepted (albeit unevenly across space) as a powerful global norm. How this came to be is a story widely told in the transition from feudalism to capitalism.34 The forcing of cogredience in our contemporary world arises in the first instance out of the dual powers of state apparatuses and of capital. The effect is to impart (and in some instances to impose) a distinctive spatio-temporal order to the circulation and accumulation of capital and to the bureaucratic coordinations necessary for the state to support the infrastructures required for capital accumulation. These impositions have wide-ranging secondary effects. It is not hard to trace the ways, for example, in which a standardized spatio-temporal discipline penetrates into daily life (our eating and sleeping habits, for example). Foucault is therefore right to suggest that general disciplinary apparatuses, as well as those specifically constructed in various institutional settings (hospitals, prisons, schools, factories, homes) together constitute a system of governmentality that operates through specific spatio-temporal orderings. We all tend to internalize a certain normative sense of a hegemonic spatio-temporality as a result. But this process is not free of internal contradictions (as well as external resistances). To begin with, the circulation and accumulation of capital is not a stable process. It is perpetually changing because of the pressures of competition and the disruptions of periodic crises. One mode of resolution of its crisis tendencies is to accelerate circulation processes (speed up production, exchange, and consumption) and to transform space relations (opening new territories and geographical networks for accumulation). The spatio-temporality of capitalism is therefore in perpetual flux. The relative space-time of exchange relations is particularly sensitive to the mediating technologies of movement (chiefly transport and communications). The effect, however, is to reconstitute definitions right across the matrix. The absolute space of the factory, if it continues to exist at all, no longer has the meaning it once did as relative and relational spatio-temporalities shift. The absolute space of the city has to accommodate to the exigencies of rapid shifts in circulation. The predominant scale (and there is now an immense literature on this) at which spatio-temporality is registered also shifts. The time and space of the world market become compressed. The absolute space of the nation-state then acquires a different meaning as the scalars of economic action in relative space-time shift, posing problems for the contemporary definition of sovereignty and citizenship. Events like the global antiwar protests of February 15, 2003, postulate a different kind of relationality (dependent upon a relative space-time world now made more possible by technological shifts in communications). Again, pressures are mobilized on the absolute spaces of territorial powers from a different direction, one that puts constraints upon the idea of territorial sovereignty as the primary container of power. And then there is the issue of resistance and divergence. Not all activities—as Moore, for one, correctly notes—are incorporated into the shifting spatio-temporal logic of capitalist accumulation.

Politics

In her book Radical Space, Margaret Kohn sets out to explore the role that space has played in politics. She is particularly interested in the ways space is implicated in the articulation of transformative political projects. This contrasts with the more familiar imaginary, largely derived from Foucault, of space as integral to a disciplinary regime of power. Kohn focuses attention on the way in which subaltern classes, often under adverse conditions, “created political spaces that served as nodal points of public life.” She examines how, for example, the creation of “houses of the people” in many European cities at the beginning of the twentieth century served both practically and symbolically to shape the ideals and practices of radical socialist democracy in opposition to the dominant forms of class power. Space, she argues, “affects how individuals and groups perceive their place in the order of things. Spatial configurations naturalize social relations by transforming contingent forms into a permanent landscape that appears immutable rather than open to contestation. By providing a shared background, spatial forms serve the function of integrating individuals into a shared conception of reality. . . . Political spaces facilitate change by creating a distinctive place to develop new identities and practices. The political power of place comes from its ability to link the social, symbolic, and experiential dimensions of space. Transformative politics comes from separating, juxtaposing, and recombining these dimensions.”35

Like Lefebvre, Kohn accepts that space has corporeal, symbolic, and cognitive dimensions. She pays particular attention to relationality: “The meaning of a space is largely determined by its symbolic valence. A particular place is a way to locate stories, memories and dreams. It connects the past with the present and projects it into the future. A place can capture symbolic significance in different ways: by incorporating architectural allusions in the design, by serving as a backdrop for crucial events, or by positioning itself in opposition to other symbols. Its power is a symptom of the human propensity to think synecdochally; the chamber of labor, like the red flag, comes to stand for socialism or justice. It is a cathexis for transformative desire. The physical environment is political mythology realized, embodied, materialized. It inculcates a set of enduring dispositions that incline agents to act and react in regular ways even in the absence of any explicit rules and constraints.”36

Kohn is particularly insistent in adumbrating the totality of interrelations. While history remembers the Turin Factory Councils of 1917–18, she complains, it largely ignores the critical role of the Turin Cooperative Alliance. It was through the latter that workers linked “disputes over the control of production to consumption and leisure, building coalitions between workers and potential allies and transforming struggles rooted in daily life into politics.” Through these mechanisms, largely articulated through the houses of the people rather than through the factory, workers “created local and regional geographies of power.” The house of the people was a “microcosm of the outside world, combining the spheres of consumption, production and social and political life, but in a more just, rational and egalitarian form.” It was “both an organization of resistance and the attempt to institute a universal.” In short, it housed and gave symbolic meaning to a localized attempt to define a progressive cosmopolitan project.37

Though mainly concerned with a particular place (Italy) and time (the period of formation of socialist movements from the 1890s until the late 1920s), Kohn’s work offers support for the general nature of the argument I wish to make. It shows how the spaces of politics and the dialectics of space-time are consequential for and formative of activities of struggle, on the part of those seeking to sustain and consolidate their existing power and of the innumerable social groups, factions, and classes ranged against them, seeking alternatives. The possibility of an alternative cosmopolitanism built upon this process is palpably evident. But care is required in articulating such possibilities. Kohn cannot, for example, provide us with prescriptive lessons or a mechanical model to follow. The historical geography of global capitalism has evolved in such a way as to make the spatio-temporal forms of resistance of yesteryear increasingly irrelevant to the current situation. While the houses of the people still exist as instructive historical markers, it would be rank nostalgia to attempt a contemporary reconstruction of their social and political meanings. This is not to say that analogous efforts are redundant. In Italy in our times, for example, feminist activists have built somewhat similar centers as part of a networked organization for political action. It therefore becomes even more important to get the theory of spatio-temporality for this kind of political work right. And on this point Kohn, like many other analysts, wobbles somewhat by being rather too impressed by Foucault’s formulation of heterotopia as an appropriate theoretical framework. So let us look more closely at Foucault’s formulation of the problem.

Foucault first articulated the idea of heterotopia in The Order of Things, published in 1966. He reflected further on its possibilities in a lecture entitled “Of Other Spaces” delivered to architects in 1967. That lecture was never revised for publication (though Foucault did agree to its publication shortly before he died). Extracted by his acolytes as a hidden gem from within his extensive oeuvre, the essay on heterotopia has become a means (particularly within postmodernism) whereby the problem of Utopia could be resurrected and simultaneously disrupted. Foucault appealed to heterotopia to escape from the “no place” that is a “placeful” Utopia. Heterotopia encompass sites where things are “laid, placed and arranged” in ways “so very different from one another that it is impossible to define a common locus beneath them all.” This directly challenged rational urban planning practices as understood in the 1960s, along with the utopianism that infused much of the movement of 1968. By studying the history of spaces and understanding their heterogeneity, it became possible to identify absolute spaces in which difference, alterity, and “the other” might flourish or (as with architects) actually be constructed. This idea appears attractive. It allows us to think of the multiple utopian schemes that have come down to us through history as not being mutually exclusive (feminist, anarchist, ecological, and socialist utopian spaces can all coexist as potentia). It encourages the idea of what L. Marin calls “spatial plays” to highlight choice, diversity, difference, incongruity, and incommensurability. It enables us to look upon the multiple forms of transgressive behaviors (usually normalized as “deviant”) in urban spaces as important and productive. Foucault includes in his list of heterotopic spaces such places as cemeteries, colonies, brothels, and prisons.38

Foucault assumes in this piece that heterotopic spaces are somehow outside the dominant social order or that their positioning within that order can be severed, attenuated or, as in the prison, inverted on the inside. They are construed as absolute spaces. Whatever happens within them is then presumed to be subversive and of radical political significance. But there is no particular reason to accept this assumption. Fascists construct and use distinctive spaces, as do Catholics and Protestants (churches), Muslims (mosques), and Jews (synagogues), as bases for their own versions of a universal and in many respects cosmopolitan project. Under Foucault’s formulation, the cemetery and the concentration camp, the factory and the shopping mall, Disneyland, churches, Jonestown, militia camps, the open-plan office, New Harmony (Indiana), and gated communities are all sites of alternative ways of doing things and therefore in some sense heterotopic. What appears at first sight as so open by virtue of its multiplicity suddenly appears as banal: an eclectic mess of heterogeneous and different absolute spaces within which anything “different”—however defined—might go on. Ultimately, the whole essay on heterotopia reduces itself to the theme of escape. “The ship is the heterotopia par excellence,” wrote Foucault. “In civilizations without boats, dreams dry up, espionage takes the place of adventure and police take the place of pirates.” But here the banality of Foucault’s concept of heterotopia becomes all too plain. The commercialized cruise ship is indeed a heterotopic site if ever there was one; and what is the critical, liberatory, and emancipatory point of that? Foucault’s words could easily form the text of a commercial for Caribbean luxury cruises. His heterotopic excursion ends up being every bit as banal as Kant’s Geography. Worse still, the absoluteness of the space confines, pointing to segregation and stasis rather than progressive motion. I am not surprised that he left the essay unpublished. What is surprising is how widely the essay had been taken up as somehow definitive of ways to define liberatory spaces.

Foucault obviously sensed, however, that something or other was important about spatiality, so that he could not let the issue die, either. He later worried, perhaps with a critique of his own concept of heterotopia in mind, at the way “space was treated as the dead, the fixed, the undialectical, the immobile,” while “time, on the contrary, was richness fecundity, life, dialectic.” Though it points to critique, this very formulation ends up reaffirming his acceptance of the Kantian view that space and time are separable from each other. If “space is fundamental in any form of communal life,” he later observed, then space must also be “fundamental in any exercise of power.” And in his lectures published as Security, Territory, Population, he recognizes the significance of absolute spatial ordering as part of the disciplinary apparatus—what he called governmentality—that emerged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and the tension between that ordering and the dynamics of circulation of commodities: people, on the one hand, and the structuring of milieu (place and environment), on the other. But by refusing, when interviewed by the editors of the geographical journal Hérodote, to elaborate on the material grounding for his arsenal of spatial metaphors, he evades the issue of a geographical knowledge proper to his understandings (even in the face of his use of actual spatial forms, such as panopticons and prisons, to illustrate his themes). Above all, he fails, as I argued in chapter 1, to give tangible meaning to the way space is “fundamental to the exercise of power.”39

Lefebvre, however, fashioned an alternative view of heterotopia. In The Urban Revolution, published in 1968, a year after Foucault’s lecture (of which Lefebvre almost certainly learned from his friends in architecture), Lefebvre set out a counter-definition. He understood heterotopias as spaces of difference, of anomie, and of potential transformation, but he embedded them in a dialectical conception of urbanization. He kept the idea of heterotopia in tension with (rather than as an alternative to) isotopy (the accomplished and rationalized spatial order of capitalism and the state), as well as with utopia as expressive desire. Lefebvre well understood that “space [and space-time] changes with the period, sphere, field, and dominant activity” and that it is suffused with “contrasts, oppositions, superpositions and juxtapositions.” As a consequence, “the isotopy-heterotopy difference can only be understood dynamically. . . . Anomic groups construct heterotopic spaces, which are eventually reclaimed by the dominant praxis.”40 The differences captured within the heterotopic spaces are not about segregation and separation, but about potentially transformative relations with all other spaces (as in Kohn’s examples). The political problem is to find ways to realize their ephemeral potentialities in the face of powerful forces that work to reclaim them for the dominant praxis. The urban women who founded educational institutions like Bryn Mawr College in the late nineteenth century thought of them as places where a distinctively feminist education could go on, but the story of these colleges is very much about their reabsorption as sites for the reproduction of dominant class and gender relations. Lefebvre’s invocation of relative and relational meanings (underscored by the very idea of “the production of space”) contrasts with Foucault’s heavy emphasis upon the concept of absolute space (even as he invokes the relative space-times of circulatory processes). In Lefebvre’s hand, the concept of spacetime becomes both dialectical and alive (potentially progressive and regressive), as opposed to dead and fixed.

It is unfortunate that Lefebvre’s dialectical conception is not better known, because the frequent appeal to Foucault’s static and rather sterile conception of heterotopia (as opposed to Foucault’s later and somewhat looser formulations) invariably exercises a baleful and deadening influence on understandings of progressive possibilities. This was the case, as we saw earlier, in Deshpande’s investigation of the relations between globalization, conceptions of the Indian nation, and the construction of “Hindu-ness” (or “Hindutva”). Kohn, for her part, narrowly avoids a similar fate by setting Foucault aside in favor of a more robust implicit theory, in which Lefebvre’s more dialectical approach has greater purchase. Moore, likewise, takes the Foucauldian insight on how spatiality and power connect in the theory of governmentality and liberates it from its absolute qualities by injecting the Lefebvrian sense of relationalities into his analytic framework.