1

BEYOND COLORBLIND

Michael, a twenty-four-year-old black man, was sharing with his small group about some hurtful experiences with racism that he had endured in the past year.

An elderly white woman tried to respond to his sharing with grandmotherly kindness.

“Oh Michael, when I see you, I see you. I don’t see your color.”

Michael didn’t know what to say, so he said nothing. But internally he thought, I’m a black man from Los Angeles. If you don’t see my color, you might as well not see me at all.

Using the paradigm of colorblindness, the woman was trying her best to affirm Michael’s humanity and dignity. She was trying to say, “I’m not one of those racist people who thought color was a reason to degrade you.”

But what Michael heard was invalidation: I don’t see you.

Why did they miss each other?

THE LIMITS OF COLORBLINDNESS

In the past, seeing color meant believing that society should be unevenly and unjustly divided by color. Today, many see colorblindness as a corrective to the problems of racism and prejudice. People who are eager to separate themselves from overt racists like to declare themselves colorblind.

You might have picked up this book for one of two reasons: you believe in colorblindness, or you’re disenchanted by it. If you’re the former, you might see our present diversity in the United States and across the world as the triumph of a diverse, colorblind society. Colorblindness and diversity are celebrated in universities, workplaces, and churches alike. We elected a black president, not once, but twice. Surely these are signs of a post-racial society.

However, in 2015, a twenty-one-year-old white man killed nine parishioners and pastors that had welcomed and prayed with him at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, a historic black church in Charleston, South Carolina. When he was apprehended, the man confessed to wanting to start a race war between white and black. He was a self-proclaimed white supremacist.

This massacre is only one of the many stories of heartbreak and injustice affecting the black community. Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and Sandra Bland have become the known names of black men, women, and children who died at the hands of white men and law enforcement officials who were not indicted. The public outcry against these and many other deaths of black Americans at the hands of police led to the Black Lives Matter movement. Some insist that education is the answer to eliminating racism, but our universities don’t seem any better. In recent years, students vandalized Northwestern University’s interfaith chapel with ethnic and homophobic slurs. Harvard Law School students placed strips of tape across display photographs of black professors. White dorm-mates at San Jose State bullied a black student, calling him the N-word and three-fifths of a person while repeatedly forcing a bike-lock chain around his neck. If education is the answer to racism, why do even our top schools seemed plagued by racial brokenness?

On top of this, Muslim Middle Eastern students at North Carolina State University were shot and killed in an altercation with a white neighbor in 2015. An Asian couple and a Puerto Rican man were gunned down by a white neighbor in Milwaukee for “not speaking English.” The election campaign of 2016 exposed all sorts of rhetoric against Mexicans, immigrants, Muslims, and more. White nationalist movements are more visibly public. Similar nationalist, anti-immigrant, and anti-refugee mantras reverberate through Europe and the rest of the world.

We are not a colorblind society. These issues are not colorblind. They are racially and ethnically charged.

In a documentary about racial peace, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Dr. John Hope Franklin discuss the colorblind issue. Franklin says there are people who think “we don’t need to do anything about the problems that we have” and “just think colorblind and the problems will themselves disappear.”1 Tutu and Franklin assert that colorblind people have a hard time seeing the existing racial inequality and injustice. Individuals claiming colorblindness cannot address racial issues that they cannot see.

Naomi Murakawa, a professor in African American history, writes, “If the problem of the twentieth century was, in W. E. B. Du Bois’s famous words, ‘the problem of the color line,’ then the problem of the twenty-first century is the problem of colorblindness, the refusal to acknowledge the causes and consequences of enduring racial stratification.”2 This might be why you are in the second camp of being disenchanted with colorblindness, because you’ve found that colorblindness does little to help dismantle existing injustice. In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander helps document the reality that today the United States holds more black adults in correctional control (prison, jail, probation, or parole) than the total number of slaves that existed before the abolition of slavery.3 It’s slavery in the twenty-first century by another name. If you are part of an ethnic community that is struggling with the lasting effects of racism on your personal life and family, colorblindness isn’t much comfort in your time of need.

The second point that Tutu and Franklin raise is that differences are not inherently bad. In fact, according to Tutu, “differences are not intended to separate, to alienate. We are different precisely in order to realize our need of one another.”4 Colorblindness seems to deny the beautiful variations and cultural differences in our stories. How would you feel if you shared something that’s part of your Chinese, black, Irish, or Colombian background, and someone replied, “I’m colorblind!”? Blind to what? The food, stories, and cultural values that make up the valid and wonderful parts of who we are?

Colorblindness, though well intentioned, is inhospitable. Colorblindness assumes that we are similar enough and that we all only have good intentions, so we can avoid our differences. Given the ethnic tensions exposed by the 2016 election, we’re seeing instead that our stories are different, and those differences cannot be avoided. Racially charged, ethnically divisive comments flood our social media outlets and news screens. Good intentions alone are ineffective medicine for such scars. The idea that we have transcended ethnic difference has been exposed as a mirage.

We don’t live in a world that is in need of colorblind diversity because diversity that rests on colorblindness seems to lead to chaos. We need something beyond colorblindness, something that both values beauty in our cultures and also addresses real problems that still exist in our society decades after the civil rights movement.

THE SILENCE OF OUR WELL-INTENTIONED CHURCHES

Our churches often avoid the topic of ethnicity and race because we don’t think it’s relevant to our faith, or we’re afraid of offending people and trying to avoid being “political.” More often than not, we don’t know how to talk about it and withdraw from conversations about race or ethnicity. We lack the skills, language, and understanding to be able to share the gospel in our diverse and divided contexts.

Perhaps the reason Christians have little to say is that, for a time, we bought into the secular world’s gospel of colorblind diversity as the answer to our problems of ethnic division. Colorblindness often meant polite avoidance or silence, inside and outside the church.

Problems with Colorblind Diversity in the Church

-

■ Lack of biblical literacy on ethnicity

-

■ Lack of understanding self

-

■ Lack of understanding others

-

■ Irrelevant, harmful witness and stewardship that causes more harm and pushes people away from the gospel and from trusting Jesus

-

■ A distant, ineffective church

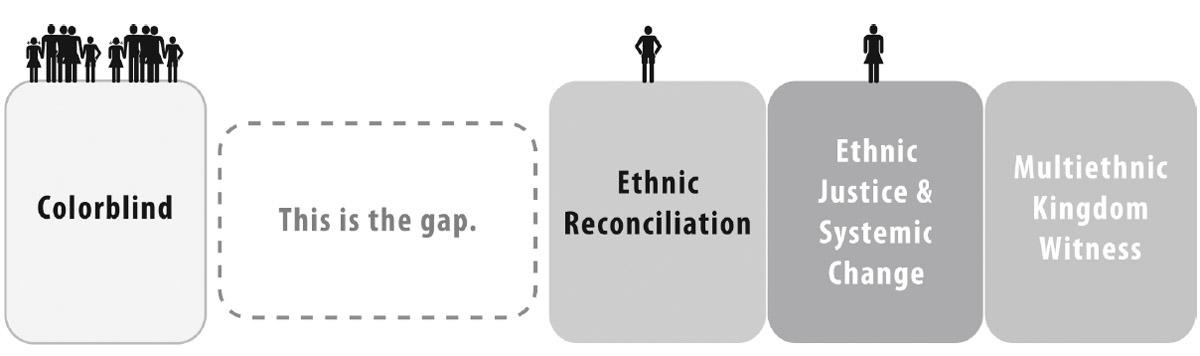

Instead of being a prophetic voice, many churches also opted for colorblindness (see figure). In buying into colorblindness, we did not examine the Scriptures’ rich depth of insight into God’s creation and intent for ethnicity, and we lacked biblical literacy on the issue, leading to lack of theological reflection, formation, and repentance. Scripture formed no foundation for ourselves as ethnic beings. We either denied ethnicity as valuable or bought into the secular world’s understanding of ethnicity. This robbed us of the opportunity to hear the stories of people who are ethnically different than us. We are shocked and unsure of how to engage when we hear of things such as a race-related incident or hate crime. Our lack of ethnic identity understanding for ourselves and those around us led to a proclamation of a gospel that is irrelevant or powerless in addressing real aches, pains, and questions. Racially and culturally unaware witness and involvement in our communities caused distrust; we sometimes did more harm than good and pushed people away from us—away from opportunities to hear the gospel and away from trusting Jesus. What resulted was and is a distant and often irrelevant, unaffected church.

The Christian story is one that acknowledges that we are fundamentally broken. Why would the realm of ethnicity and race be exempt from the influence of sin? Colorblindness mutes Christian voice and thought from speaking into ethnic brokenness. In holding onto colorblindness as the solution, we as Christians are trying to doggy-paddle when we actually need to learn how to swim. We might sink in our attempts to stay afloat or cause others to drown as we thrash about in our good intentions.

Our world is in need of the gospel, a good news that goes beyond colorblindness that is not afraid of addressing ethnic differences. When it comes to ethnicity, our world needs Christian voices to call for change and reform with Jesus as the transforming center of it all. How can we relevantly live out the gospel in such a hotbed of emotions, scars, division, and chaos? If we avoid this topic now, we withdraw into ineffectual witness in word and deed. And we leave a broken and hurting world, friends and strangers, in chaos.

Figure 1. The colorblind gap

GOING BEYOND COLORBLINDNESS

When Michael was told “I don’t see your color” by the older woman in his small group, he heard something like this: “I don’t want to hear about or acknowledge some of the most beautiful parts of who you are ethnically and culturally, and I don’t want to walk with you in the pain of what you have experienced racially.”

This was a Christian-to-Christian interaction that yielded invalidation and distrust. How much more harm might have been done if this had been a conversation between a Christian and nonbeliever?

Suppose you find out that a friend was sexually assaulted or harassed. As you speak with the friend, you say, “I care about you and you’re my friend, but talking about what happened to you makes me uncomfortable. So can we talk about all the other things we have in common and avoid this painful part of your life because it’s awkward and uncomfortable for me? Thanks.” What would your friend say? That’s probably the end of the friendship because you’re clearly not acting as a real friend. You’re conveying that this friendship is about your own convenience and comfort—an act of selfishness and self-protection that bruises Christians and non-Christians alike.

Oscar Wilde writes,

If a friend of mine gave a feast, and did not invite me to it, I should not mind a bit. But if a friend of mine had a sorrow and refused to allow me to share it, I should feel it most bitterly. If he shut the doors of the house of mourning against me, I would move back again and again and beg to be admitted. . . . If he found me unworthy, unfit to weep with him, I should feel it as the most poignant humiliation.5

Real friends aren’t afraid of looking at a friend’s real scars. And the scars that people experience in their culture, ethnicity, and race are places that need the gospel. Evangelism without real friendship and community without real concern for the needs of others is a hollow-sounding, empty gong.

Our ethnic scars are not always racial. Sometimes they are from idolizing things that our ethnic cultures prize. For example, in Asian cultures that emphasize family honor, honoring parents has often meant unequivocal obedience to the parents’ dreams of financial success and prestige for their children, often at the cost of a child’s dreams and desires. Language, worldview, and generational differences exacerbate some of the relational difficulties between parent and child. This, combined with something akin to the mentality of “saving face” for the family’s reputation, can lead to broken family relationships, resentment, or mental health issues such as depression and anxiety. Non-Asian friends and pastors often try to counsel Asian Americans by giving them suggestions that are distinctly non-Asian, and these solutions end up causing more problems. Our ability to love and live out the gospel relevantly involves engaging the reality of ethnicity.

Instead of being colorblind, we need to become ethnicity aware in order to address the beauty and brokenness in our ethnic stories and the stories of others (see figure). But this is a road with treacherous ditches and potential roadblocks, and conversations full of tension, confusion, accusation, pain, and shame. Some of us represent the oppressed or the oppressor, ethnic enemies, strangers. We’ve seen conversations about race and ethnicity go south, real fast. What difference does Jesus make in this journey?

Figure 2. Ethnicity awareness fills the gap

KINTSUKUROI: THE ART OF RESTORING AND RECLAIMING

Pottery is an ancient and highly respected practice in Japan, and each vessel is made with great care and thought about the piece’s balance, shape, and feel. With Kintsukuroi, the Japanese practice in ceramic art meaning “golden repair,” broken pottery is repaired by setting it back together with an intentionally brilliant golden or silver lacquer. This method highlights each piece’s unique history by emphasizing the fractures instead of hiding them. Often, the final work is even more beautiful than when the piece first came into being.

When Jesus shapes our ethnic identities, he is like the gold seam in Kintsukuroi. He demonstrates how each of us in our ethnic backgrounds and identities were made for good in the image of God, like beautiful pieces of pottery. But sin—in the form of cultural idolatries, ethnic division, and racism—causes damage, brokenness, and painful cracks in the story of our ethnic identities. When unattended, many of those cracks deepen into bitterness, prejudice, revenge, racism, hatred of others, self-hatred, depression, suicide, numbness, despair, and idolatry that we pass on to our children. God is not content to leave us to our brokenness, and he sends Jesus to redeem us in all of who we are. As children of God, we die with him in his crucifixion and rise with him in his resurrection.

Jesus’ resurrection did not get rid of his scars. His scars remind us of the broken story of humanity and the powerful, costly love that came to save and mend us. As in Kintsukuroi, when Jesus enters our stories, the healing, redemption, and reconciliation he brings is the undeniably striking golden seam. Kintsukuroi doesn’t deny the brokenness of the pottery—it uses it to tell a new story. Likewise, our scars become transformed by Jesus’ scars. And it is the beauty of that story that allows us to share the gospel with those around us. We are most fully able to share the gospel when we can share about its impact on all of who we are. And when those diverse pieces come together as one body and share the myriad of stories of healing, reconciliation, and sacrificing for the other, we are a visibly powerful vessel of kingdom witness.

THE DREAM OF WHAT COULD BE

Kristin is a forty-year-old white ministry leader who spoke of the history of both abolitionists and slave owners in her family line during an outreach event. She apologized on behalf of white people to the people of color who had experienced racism from white people. She wasn’t doing this because she was ashamed of being white; she knew that just as she represented the community of Christians to nonbelievers in the room, she also represented white people to the nonwhite people in the room. And she wanted to both preach the gospel and serve as an ambassador of reconciliation spiritually and ethnically. James, her thirty-year-old black colleague and close friend, also shared about his journey as a black man. Together, they spoke of how Jesus made them well and was healing them of lies, sin, racism, and brokenness, and they invited others to experience the same.

As a result of their discussion, a young white man named Erik became a Christian. Shyla, the black woman who had invited Erik to the event, wept as she watched Erik say yes to Jesus, not in spite of him being white, but because of who he is as a white man. Several black students also came up to Kristin, marveling, “I’ve never heard a white person talk like you before.” One of them was Devon, a nonbeliever, who could barely find words to describe the Holy Spirit encounter he had during the time of closing prayer as Kristin had asked Jesus to bring healing to those who had experienced brokenness in their ethnic identities. “I don’t know what happened to me,” Devon said as he spoke of being flooded with warmth and the strange sensation of being deeply loved.

Kristin laughed and said, “I think Jesus happened to you.”

Looking at her, Devon replied steadily, “Well, then you must have a whole lot of Jesus in you.”

You must have a whole lot of Jesus in you. This was a comment from a non-Christian black man who was undeniably affected by the story of a white woman sharing about how Jesus was redeeming her ethnic identity as a Christian white woman.

This is a beautiful story—the dream of what could be. But how do we get there?

START BY NAMING OUR ETHNIC BACKGROUNDS

Just as the process of making Kintsukuroi art can’t happen without distinct, identified pieces of pottery, the process of healing can’t start until we name and acknowledge that we all have an ethnic background. Our ethnic identity and background is experienced culturally and racially in our context, in the languages we speak, in our family histories, and in the stories of our ethnic communities.

Ethnicity is more distinct and specific than race (Norwegian versus white, Taiwanese versus Asian). Ethnicity refers to common ancestry, tribe, nationality, and background, often with shared customs, language, culture, values, traditions, and history. Race, on the other hand, is the classification of people according to their supposed physical traits and ancestry. Race, though a manmade historical construct, has real-life present day realities. Power, access to employment and education, and social status historically have been unevenly applied to racial groups, leading to slavery, segregation, apartheid, and obstructed civil rights. For the sake of conversation, we need to be able to name and group people using commonly understood terms, even if those terms are limiting. Thus, this book will refer to continental groups of people by their racial categories (or in the case of Latino, their ethnic-cluster categories), which include ethnic diversity and also acknowledge racial histories and realities.

Black refers to those of African descent, including those whose ancestors were brought over as slaves (African American, African Canadian) as well as more recent migrants of the Caribbean (Haitian, Jamaican, Trinidadian, Barbadian) and Africa. A black American and a black South African have vastly different stories, though both of their peoples experienced racial oppression. They will have a different story from a Nigerian or Kenyan national who grew up as the ethnic majority or a tribal minority.

Asian refers to all of Asian descent, including the earliest Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, and Indian migrants to the United States as well as the later waves of Korean, Taiwanese, Lao, Cambodian, Bengali, Vietnamese, Hmong, Thai, Sri Lankan, and several other Asian ethnic groups. An Indian Canadian or Asian American have both ethnicities and nationalities that are integral parts of their story. They will have different experiences from Asians who grow up in Asia or other parts of the world.

Latino encompasses those who were annexed in during the formation of the United States as well as the great diaspora of Central American, South American, and Caribbean people from Mexico, Panama, Chile, Brazil, El Salvador, Honduras, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and more. Contrary to popular understanding, the US Census Bureau defines “Hispanic or Latino” as an ethnicity: “a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race,”6 as Latinos can be white, black, brown, or other (for example, there are black Cubans, white Mexicans, Native Paraguyans, and everything in between). Some Latino communities use Hispanic and Latino interchangeably. Others prefer Latino because the “span” in Hispanic is a reminder of the colonizing legacy of Spain. To honor those who are uncomfortable with Hispanic, we will use Latino in this book.

Middle Eastern refers to those that are descended from the transcontinental region centered on Western Asia and Egypt, including countries such as Iraq, Turkey, Syria, and Iran.

Native refers to the hundred-plus tribes that exist today, including Pacific Islander and Hawaiian. Lakota, Navajo, Sioux, and Cherokee are a few of the many known tribes. First Nations is the name that Canada uses, which acknowledges the earliest presence of Native communities in North America.

White refers to those of the European diaspora, from the earliest Western European colonialists to past and present day immigrants from Northern, Southern, and Eastern Europe as well. Some white people can definitively trace their history back multiple generations, while others have so many different European ethnic heritages in them that “white” really is the best way they can describe their pan-European ethnic and racial background. This can feel jarring in particular to people who are not accustomed to thinking of themselves as “white” in their countries of origin.

White Americans have often thought of themselves as not having an ethnicity, as if ethnic is a politically correct term replacing people of color. But the Greek word ethnos means the nations, and we each are descendants of ethnos. This is true for those of us who are multiracial, who are adopted by parents of a different ethnic or racial group, or who resonate with being third-culture children (people who grew up in a culture different from that of their parents). None are excluded from the invitation to recognize their ethnicity and invite Jesus in.

When Americans of every ethnic background enter into a multiethnic community, they possess differing levels of understanding of their cultural and racial backgrounds. Black Americans tend to have more defined language for both culture and race, as both are talked about at the family dinner table. Asian and Latino Americans, by contrast, often have stronger self-identifying language for culture while they vary in having language for a racial identity. Add white Americans into the mix, and you have a people who often lack self-identifying language for culture and race. The first conversation about race is disorienting for white people, as it usually involves learning about racial oppression caused by whites. The result is a double deficit: lack of cultural identity and a negative racial identity.

When you have a room full of people who have varying levels of language, experience, and awareness, a conversation about ethnicity and race is difficult. It’s like trying to run a marathon with a group of marathon veterans alongside sprinters, casual joggers, and couch potatoes. It makes for chaos, misunderstanding, and a good measure of frustration and heartache. There is a great need for understanding our own stories for the sake of our individual stewardship and witness as well as the corporate witness of an evangelistic community.

We need to fully know our stories in order for Jesus to fully do his work. To use a Kintsukuroi analogy, if I were a blue teacup that has experienced brokenness and cracks, my hope is not to be made into a gold-veined green vase! The Potter made me into a blue teacup, and Jesus delights in restoring me to be what I was meant to be. He heals my blue teacup cracks so that I can share my restored story with others.

HOW JESUS SHAPED MY ETHNIC STORY

I remember coming into college very aware of the faults of my Korean American culture, and in particular, its destructive anger. I grew up hearing stories about how Japan had occupied, mistreated, raped, and pillaged Korea. I felt that scar on Korea’s consciousness and saw that hatred in many Korean families. I was raised and bred to resent Japan. I watched destructive arguing, stubbornness, and divisiveness plague my family and realized with horror that I too was full of damaging anger—at the family brokenness, the poverty we’d faced, and the racism my parents endured. I watched Korean American classmates start race-based arguments with other ethnic groups at my public high school in New Jersey, causing division even among the Asian community. The phrase “make like a Korean church and split” was something that I and many other Korean American churchgoers regularly experienced. Many left the church, disillusioned.

By the time I got to college at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, I was nearly ready to reject my ethnicity, or at least to label it as impossibly broken forever. The Asian and white churches of my youth never addressed the reality of racial tensions that existed in my high school nor the realities of cultural idolatry and family brokenness that tore apart many Asian immigrant families. Faith seemed divorced from reason, and if reason existed, it didn’t acknowledge my culture. I was tired of being part of an irrelevant faith that seemed powerless to address the real issues my non-Christian friends and I were facing.

To my surprise, I found myself drawn to a group of believers who were dominantly Korean American but were working hard to reach out to their Asian American friends (as well as white and Jamaican). I floundered in multiethnic spaces because I didn’t know how to operate in them. I didn’t know what it meant to be a Korean American Christian. But with this group of women and men, faith was not only comforting, it was also compelling. They talked regularly about what it meant to be Asian American and follow Jesus, and about how to pursue hospitality together and break down dividing walls between Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese, and Japanese people. White men and women speakers shared about their own journeys in engaging race and ethnicity. Black ministry leaders spoke about engaging racial injustice and poverty. We talked about the challenges of honoring our Asian parents while not agreeing with all of their values; we discussed forgiveness and healthy conflict resolution versus the falseness of “saving face and pursuing harmony” at any cost.

It was here that I was challenged not just to follow Jesus on Sunday but also to submit my whole life, including my Korean American family and its pain, to Jesus. I asked him to renew my family instead of assuming that my parents, like other Korean parents, would always be broken. It was pivotal in helping me learn to have a real relationship with a father with whom I clashed so much. Jesus was healing my relationship with my father, and I didn’t have to become a white Christian for this to happen. After I sent my father a photo album expressing my love and gratitude for his many sacrifices, my mother told me that he spread that album out on his desk and wept for hours. Our relationship had been so broken, but Jesus was helping both of us heal.

My friend Paula, a Chinese American agnostic, opened up to me about her own life as I shared with her about how Jesus was changing my relationship with my father.

“You should try praying and asking God to show up,” I said.

“You think he’d listen even if I’m not a Christian?” she asked.

“Yes,” I responded with confidence, while silently praying, It’s on you, Jesus, if she doesn’t hear back!

Slowly, she started praying and asking Jesus for help, and slowly, she started to see real changes in how she and her mother were relating to each other. Years later, I got an email from Paula saying that she had decided to become a Christian and was getting baptized in the Pacific Ocean.

“I wanted to tell you,” she said, “because you were the first person that told me about Jesus.”

I wept when I got that email. Paula had grown up in Alabama, where the only time God was mentioned to her was when churchgoing Christians told her she was going to hell because her family was agnostic. When she saw that the gospel had relevance to her family story—her ethnic story—she gave Jesus a chance.

THE IMPACT OF JESUS REDEEMING OUR ETHNIC STORIES

We need to recognize what we are meant to be in our ethnic stories and identities so that we can ask Jesus to restore us. It’s not just about being racially aware and sensitive so that you can be a crossculturally savvy navigator of a multiethnic group. It’s also about Jesus redeeming and restoring our ethnic identities, which makes for a compelling narrative that causes non-Christians to ask us about our faith as they wonder, how could that kind of hope and healing be available to me?

When Jesus interacts with the Samaritan woman at the well in John 4, she responds with astonished cynicism: “You are a Jew and I am a Samaritan woman. How can you ask me for a drink?” (John 4:9).

Jesus’ attempts at conversation are parried by the woman’s multiple pointed questions about their people’s historic ethnic tensions. But by choosing to speak with her, Jesus the Messiah is embodying what Israel was meant to be: the priesthood nation and light to the Gentiles. He is redeeming what it means to be an Israelite Jew. And as the Samaritan woman experiences Jesus redeeming his people’s ethnicity, she starts to desire such living water. Jesus is transforming the disciples’ understanding of what it meant to be Jewish and the Samaritan woman’s understanding of what it meant to be Samaritan. Ethnicity no longer serves as the confines of mission. It becomes the vehicle, the sacred vessel in which God’s story comes to light.

Our ethnic stories rarely form in isolation; they often involve encounters and altercations with those around us. It’s knowing our ethnic stories and the ethnic identity narratives of those around us that helps us realize the complexity of values, scars, trigger points, and words to avoid. It helps us know more how to sensitively share the gospel and boldly invite even those that were considered ethnic enemies or strangers to become believers.

Knowing and owning our ethnic narratives helps us understand the real issues of injustice, racial tension, and disunity that exist in the world. Ethnicity awareness helps us ask the question of how to prophetically engage in pursuing justice, racial reconciliation, and caring for the poor while we give the reason for our hope: Jesus, the great reconciler of a multiethnic people.

Elizabeth, a young white college minister with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship at Smith College, experienced healing as she learned about her ancestral German and English heritage, her family’s communication and conflict styles, and how her family had responded to race and other ethnicities throughout its history. She came to know that she, as a white woman, was made for good by God. Elizabeth also experienced powerful forgiveness as her black and Asian colleagues prayed forgiveness and blessing over her and her people. Something changed for Elizabeth in hearing that she was made precious as a white woman (as our society tends to view white culture either as blank or defined by white privilege only) and that she was forgiven for what whiteness has historically represented in the past. Elizabeth was commissioned to live differently and follow Jesus in a new way as a white woman. After hearing the news of black men, women, and children dying at the hands of police in multiple incidents during the fall of 2014, Elizabeth and other InterVarsity leaders felt convicted to create a prayer space for black students, even though black students didn’t usually attend their group.

To the leaders’ surprise, five black women showed up. Elizabeth asked the women to share about how the leaders could be praying for them, and the women opened up about their heartache, questions, fears, and deep grief. After an hour of weeping and praying together, the women remarked that though they had been to many university events in response to what was happening to the black community, this was the first time anyone had actually asked them how they were doing.

Because of the time Elizabeth spent exploring her own racial and ethnic story, she could reach those who were hurting and engage in their stories. She was not afraid of their stories, nor was she afraid of the historical friction that her story would uncover as it intersected with their stories because she was part of the great reconciling story of Jesus. The black women who attended the prayer space began asking how they could better reach secular black students who needed to hear about the gospel during this difficult time. Experiencing this kind of hospitality and intentionality helped them turn their eyes toward witness. Compassionate engagement in ethnicity and race led to the opening of new doors in evangelism and reconciliation.

For me, Kristin, and Elizabeth, God turned the chaos of our experiences of ethnicity and race into something else. He transformed our ethnic identities to be the vehicle of sharing the gospel.

THE INVITATION IS YOURS

No matter your ethnicity, Jesus wants to do the same with you. He wants to sanctify the space of your ethnic identity, show you where you are made in the image of God, and heal you of brokenness so that your ethnicity becomes the vehicle of mission to a broken and chaotic world. The stories I share are just some of the many I have had the privilege to hear as I train ministry leaders about engaging ethnicity, reconciliation, and evangelism in InterVarsity Christian Fellowship and other church and Christian institutions. Regardless of age, gender, ethnic background, or class, I’ve found that it’s essential for individuals and communities to recognize that we each have an ethnic identity.7 A helpful tool I use is evangelist Dr. James Choung’s framework for explaining the gospel called the Big Story, summarized below:

-

We are designed for good: we must recognize the beauty inherent in each of our ethnic identities.

-

We are damaged by evil: we must recognize the effects of sin, brokenness, idolatry, prejudice, and racism in each of our ethnicities.

-

We are restored for better: we must invite Jesus to show us what is beautiful and what he wants to heal in our ethnic identities.

-

We are sent together to heal: we must invite others to drink of the living water of Jesus so that many more can hear the good news and share that news in witness, justice, and reconciliation.8

This framework is accessible to non-Christians and Christians alike, and it helps people pinpoint where they are in their ethnic journeys. Some have never even considered their ethnicities, while others have been trapped in places of pain or confusion. The eighteen-year-old and the septuagenarian alike can have conversations about their very different experiences. The Big Story framework allows for discussion of spiritual, physical, social, emotional, and racial dimensions of one’s ethnic journey.

We are trapped behind the futility of colorblindness or the helpless impotence of our good intentions unless we choose to recognize that our ethnicities are the sacred vessels in which God wants to bring healing and redemption. We cannot be sent out with the gospel of grace unless we experience that for ourselves.

To those that would try to avoid the topic, stigmatize it as a liberal agenda, or succumb to despair, the powerful counter-response is that ethnic identity redemption and reconciliation are at the heart of the gospel. God created us for good, but cultural idolatry and racial brokenness tore apart our intended multiethnic community. Jesus came to restore us, redeem us, and release us for his kingdom mission, not in spite of our ethnicities, but in our ethnic identities. For example, if you are a white man or woman hoping to share Jesus with a black community, you need to know their context and your context in order to be able to share the gospel in a transformative way. Sharing the gospel is never about being safe or polite. It’s about loving deeply, and you can’t love what you do not know. Simultaneously, you need to not be defined by fear and shame and thus avoid opportunities to share the gospel. It’s not enough to say, “Don’t be afraid”—as bravado is not a good witness. If you know your own story as well as the story of the people you want to reach, and you humbly share a relevant gospel, you are a powerful witness.

So, in the name of hope, learn and own your ethnic identity story. The first half of this book focuses on learning your ethnic story and inviting Jesus into that space so that you can proclaim the kingdom of God. The second half focuses on how to share that story and how to steward your ethnic identity in multiracial, multiethnic spaces. Join me in exploring how Jesus amplifies the beauty and excavates the brokenness in each of our stories and unleashes those redeemed stories to better share the gospel.

QUESTIONS FOR INDIVIDUAL REFLECTION AND SMALL GROUP DISCUSSION

-

1.What messages about colorblindness did you grow up hearing?

-

2.The author argues that colorblindness denies persistent race-related problems as well as beauty in our ethnic differences. How does this compare with your own experience and the experience of your loved ones?

-

3.What is your ethnic background? Be as specific as possible. How long has your family lived in this country?

-

4.As you learn more about becoming ethnicity aware, what questions, fears, and hopes are stirring within you?

RECOMMENDED READING

“Be Color Brave, Not Color Blind,” TED blog by Mellody Hobson

Beyond Racial Gridlock: Embracing Mutual Responsibility by George Yancey

Can We Talk About Race? And Other Conversations in an Era of School Resegregation by Beverly Daniel Tatum

Disunity in Christ: Uncovering the Hidden Forces That Keep Us Apart by Christena Cleveland

“A Journey Towards Peace,” PBS interview with Desmond Tutu and John Hope Franklin

True Story: A Christianity Worth Believing In by James Choung

White Awake: An Honest Look at What It Means to Be White by Daniel Hill

InterVarsity Christian Fellowship has a Beyond Colorblind video series about ethnic identity. For a video that introduces the conversation, go here: http://2100.intervarsity.org/resources/beyond-colorblind-overview.