7

CROSSCULTURAL SKILLS IN COMMUNITY

In Cultural Intelligence, David Livermore writes, “I’m confident most ministry leaders want to love the Other. But gaining the ability to love the Other and leading others in our ministries to do the same is the journey we’re interested in.”1

During a Bible study, I watched a white man earnestly try to engage by responding to the questions, sharing his thoughts, and having a mild debate about the topic. I could tell that he thought he was offering the best of himself. But I could also see that the Asian American woman in the group, who was quiet, wasn’t very happy that the white man was always the first to speak and seemed to cut off others. I was sure she was thinking, How dare he challenge the Bible study leader publicly! That is rude and unacceptable. Meanwhile, I could see that the black woman in the group was not sure what to think of the Asian woman’s disengagement from the discussion. Was the woman checking out? How were they supposed to grow as a community if the woman seemed so closed off? And would this white man respond with some nonsense about colorblindness if I share my perspective as a black woman on the passage?

The person leading the Bible study was hoping that the group would willingly share and grow deeper in community. What he didn’t realize was that his leading method invited only those from expressive, low-hierarchy backgrounds. Inadvertently, he was reinforcing only one way of communicating. And he wasn’t trying to figure out how the group might overcome its fears or anxieties.

Once we have the skills to build trust with non-Christians, we can invite people to the table of multiethnic fellowship in Jesus’ name. But then we need to know how to be together at the table. We need to know how to communicate across cultures on a basic level. For many white Americans who grew up with mostly white friends, the learning curve is steep, as it is for Asian Americans who grew up in mostly Asian American circles or black Americans who grew up in mostly black circles. Crosscultural skills are needed in order to make a diverse, multiethnic community work.

I’ve often seen well-intentioned Christians and non-Christians alike assume that talking about diversity or ethnicity will help people live in multiethnic community. But the truth is, people don’t naturally know how to be friends across cultures. Few of us are taught by our families how to have real friendships in diverse, multiethnic networks. Even our schools teach polite tolerance that never goes deep. The floundering Christian that makes a mess at the multiethnic table is not going to be a strong witness to a non-Christian, and he definitely will be an inhospitable guest.

THE CHALLENGE OF GROUP CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

Americans (no matter our ethnic variant) represent some of the most individualistic cultures in the world.2 Individualism, the right to individual freedom and choices, makes many of us want to be seen at face value—as individuals not bound to a historical past or tethered to social hierarchy (“just call me Jane instead of Dr. Lee”). However, as you and your community experience the limitations of an individualistic framework, it will be harder to deny that you can represent a people and a history.

Let’s say an ethnically diverse group of people including Asian, black, Latino, Middle Eastern, Native, and white Americans sit together to dine. Each individual could potentially represent an ethnic group that might have hurt another group represented at the table. You can’t ask to be viewed for who you are as an individual because more than likely the people sitting across from you didn’t receive the same treatment as an individual and instead were treated differently just because of the color of their skin. Everyone at the table communicates differently and has various values that might make conversation more difficult. In fact, some natural tendencies might only reinforce ethnic and racial scars.

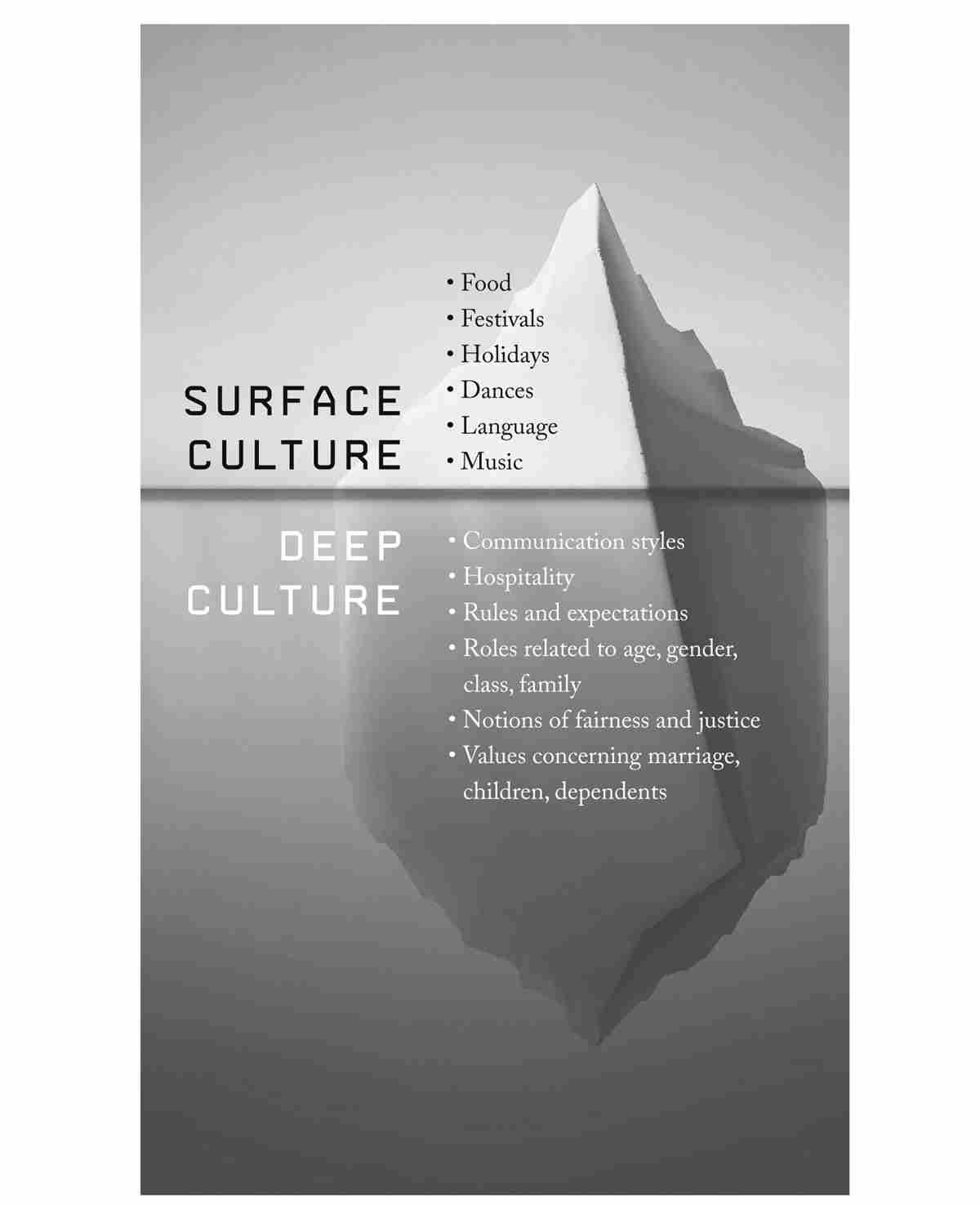

Our ethnicities have cultural norms and values. Like an iceberg, there are cultural things you can see on the surface, such as food, dance, holiday traditions, customs, and language linked to a country or province of origin (though many would argue that language is the carrier of culture). On a deeper level (the nine-tenths of the iceberg below the surface of the water), culture encompasses so much more, such as notions of hospitality, fairness, relationships with authority and elders, physical touch, and communication (see figure 3). Culture can and does shift over time, and globalization and social media continue to affect it.

Regional cultures affect our expressions of our ethnic heritage cultures. For example, Texans have a distinctive flair, as do Southerners. Latinos from New York are different from those in Los Angeles. Midwestern and New England white people are different from each other. These cultures highlight and express different values, and we express our individual personalities in these cultures. How can we communicate across such values? More importantly, how do we invite a multiethnic group of people to the table where Jesus is the host?

Figure 3. Surface culture versus deep culture

COMMUNICATING ACROSS DIFFERENT CULTURES

We must recognize that we communicate differently according to our ethnic cultures and backgrounds. Isaiah, a black man, was a leader in starting a witnessing community at a college. Isaiah is larger than life in size and personality—friendly to everyone, the center of attention. He was excited when he met a young Vietnamese American student named Luke who seemed to share Isaiah’s excitement in reaching out to new people. Luke did every task Isaiah asked him to do. He’s so committed! This is great, thought Isaiah. Then one day, Luke stopped showing up. Isaiah was confused and began to analyze what had happened. He realized that Luke wasn’t saying yes because he believed in the vision of the group—Luke was saying yes because he was too polite to say no. Luke’s actions honored his elder Isaiah, but Luke finally burned out because he kept avoiding the conflict of telling Isaiah otherwise. Isaiah, a direct person who expected to be treated more like a peer by someone like Luke (who was only three or four years younger than him), didn’t understand the indirect ways Luke was trying to communicate with him. Luke respected Isaiah but wasn’t committed to the vision for the group. There were value differences at play in this exchange. As you reach out to new communities, you’ll encounter a diversity of values that differ from your own, including communication styles, power distance, and approaches to conflict.

Direct versus indirect communication styles. Isaiah took Luke’s words at face value because he is familiar with direct, explicit communication, where what you say matters. In indirect communication, however, the way you say something matters just as much. My friend Dustin, a Taiwanese American, is notorious for answering “maybe” to something when he actually means “no.” For many people from shame-based cultures (Asian, Latino, African, Native, Middle Eastern), saying no directly to someone’s face is considered dishonoring to both parties.

High-power distance versus low-power distance. Power distance refers to your awareness of difference in age, social status, and position, and how it affects your interactions with others. People with high-power distance will defer and give more authority to someone older or with more social status. People with low-power distance will think that peer friendship and casual interaction are possible with someone significantly older or younger than they are. Isaiah thought Luke was responding to his fun, energetic vision casting for the ministry, but in reality, Luke was dutifully trying to do what his “elder” asked him to do. In American culture, we talk about people becoming adults when they’re eighteen. In Asian culture and many immigrant cultures, you are your parents’ child until the day you die. Saying no to an elder has consequences and can lead to uncomfortable conflict and broken relationships.

Books such as Crossing Cultures with Jesus or Cross-Cultural Connections emphasize the building of cultural intelligence and crosscultural skills. Don’t just learn about differences between American and overseas culture. Also search out materials that help you learn about cultural differences within the United States.

Isaiah’s story highlights a few of many possible value differences. Some of us are more motivated by individualism (individual goals and rights) while others are moved by collectivism (group goals and personal relationships). Still others of us think a democratic vote is a perfectly reasonable way of making a decision, while others of us don’t feel comfortable unless consensus is reached by the whole group. Watch an Asian American church group try to decide where to eat for dinner. Everyone’s desires and dislikes are considered, and the decision making process can take up to an hour. Obviously, collectivism and individualism as values overlap with either a consensus or democratic vote.

Conflict acceptance versus conflict avoidance. Some of us come from cultures that are okay with having conflict, while others avoid it like the plague. Compare an Italian American with a Dutch American, or a Korean American with a Japanese American. The former (Italian and Korean) will tend to be more comfortable expressing conflict and difference of opinion and might even display changes in their tone of voice and emotion. The latter (Dutch and Japanese) might be put off by that communication style or view the conflict as a breaking of trust. Black American friends have often told me, “You know we trust you when we’re willing to get real with you,” which means they can be honest about their hurts and emotions without worrying about whether they sound like the stereotype of an angry black woman or man. But for a number of white and Asian people who are unaccustomed to big displays of emotions or direct confrontation, such conflicts can break trust.

Missional teams and communities that are diverse will need to shift in how they communicate with each other, how decisions are made, and in the expression of different values. Offering hospitality to each other allows us to be better at offering the hospitality of Christ to new communities.

BUT WHAT ABOUT BEING TRULY WHO I AM?

Being authentic to your ethnic self means not acting as if your cultural values are the norm. Assuming that your way is the way everyone should be, or assuming that you don’t have to adjust when communicating with others, is a kind of cultural idolatry or self-worship. The people who learn to navigate crosscultural settings aren’t being inauthentic: they’re being good stewards of their ethnic identities to a diverse group of people.

You see this in Paul, the apostle to the Gentiles. He is vehemently opposed to circumcision as a means of proving one’s salvation. When he returns to Jerusalem, he is advised to join with four men in a vow of purification rites and shaving heads (Acts 21:24). This way, the rest of the Jews will know that Paul isn’t trying to destroy Judaism but is instead preaching about a Messiah who fulfills it. Paul complies. While Paul refuses to circumcise Titus, a Greek, to prove his salvation in Galatians 2, Paul is willing to have Timothy, a biracial Jewish and Greek man, circumcised. Is he being inauthentic by respecting the cultural norms and customs, or is he conveying respect and honor to the people that have yet to know Jesus?

When Paul goes to Philippi in Acts 16, he has to change his behavior. He can’t find a synagogue, though his standard practice is to preach the gospel first to the Jews in a synagogue. So he goes to the river where Jews are gathered and finds Lydia, a wealthy vendor, at a women’s prayer group. After she is baptized, Lydia insists, “If you consider me a believer in the Lord . . . come and stay at my house” (Acts 16:15). Paul, who tries so hard to avoid being a burden, complies and goes with her, changing his usual behavior in order to be a good witness. That doesn’t mean that he is being inauthentic.

As Jesus invites us to reach out to diverse people, we have to learn how to interact in ways that build trust, communicate honor, and extend hospitality. Instead of going to the synagogue, we might have to go to the river. This does not mean that we become less of ourselves. It means that we become more fully the people of God who invite others to the table.

LOOK FOR CULTURAL INTERPRETERS AND MENTORS

Find mentors and peers that will help you in this journey. Seek some peers and mentors who don’t look like you and some who do look like you. Crosscultural interactions can shake up a number of things in us: our need for control, our desire to seem put together, perfectionism, and our fear of failure. It’s disorienting if you’re familiar with a low-power distance, verbally expressive white or black context and then you step into a room full of high-power distance Asian Americans where you might miss indirect hints or nonverbal cues. You can feel like a fish out of water. Instead of persisting in your blunders, ask for feedback from cultural interpreters, people who are willing to help you understand cultural differences between you and your setting.

If you regularly learn from someone who looks like you, seek out a mentor of a different ethnic background who will help you learn how to navigate their context. Learn from their stories, ask exploratory questions, and invite them to speak into your life. Seek out peer friendships where you can learn from people who are ethnically different from you. To be someone’s token black or Latino friend is about appearances, not about the realness of crosscultural multiethnic community. It’s not real friendship. Instead, genuinely invite people to speak into your life from their perspective.

Along with that, seek out mentors and peers of people from your ethnic background who have experience navigating deep crosscultural friendships and multiethnic community. Just as we learn much from people who are different than us, we learn a lot from people who share our backgrounds and are able to articulate how they were shaped, transformed, and challenged by their experiences and friendships in multiethnic community. These are few and far between, but you can pray that God brings those people into your life.

My husband, Shin, is Korean American. He spent time learning about the experiences of the black community in New Haven, Connecticut—a state with one of the widest disparities in incarceration rates between black and white residents.3 As Shin was learning about black culture and systemic injustice and asking questions, he shared his fears of “urban people” with his black friends. They had journeyed with him in his learning process and looked at him with love and grace when they said, “Shin, you’re not afraid of urban people. You’re afraid of black people.” Wow, talk about an honest comment! But this honest response prompted Shin to share about painful encounters he had as a child with black children on the playground. He realized he had internalized the racism done to him and was projecting that racism onto others. For example, one of Shin’s knee-jerk reactions was to reach for his wallet every time he saw a black person get into an elevator with him. Shin’s friend Alysia would gently squeeze his arm when this happened so that he was made aware of his prejudiced reactions. Over time, Shin was able to repent and intentionally work on his behavior and attitude about black people. Now, when Shin sees black folks, he has the opposite reaction, greeting them with warmth and enthusiasm. His black friends helped him overcome his prejudices.

You can identify a good mentor by watching them share how Jesus transformed their ethnic journeys. They know and embrace who they are ethnically; they can articulate the good in their culture, talk about their brokenness that Jesus is healing, and steward who they are for the kingdom.

I have learned much from my mentor Virginia, a pastor and seminary professor at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. Virginia highly identifies with her black and Bajan (Barbados) identity. She’ll break out into a Boston accent or start dancing to the soulful funk the band is playing as she leads us in worship. One wink from her can make you smile, and one stern look can make the most obstinate man fall silent. Some affectionately call her “the velvet hammer.” Virginia navigates majority black, majority white, and multiethnic spaces by being herself. She also invites people into black sayings and humor instead of trying to deny her blackness in order to fit in. As she mentors women and men of other ethnicities, she shares with me what she is learning about cultural and ethnic differences and how it’s reflected in her leadership. Her intentional leadership helps me understand how to navigate a multiethnic world.

Another mentor is James, who is Korean American like me. James is so friendly and winsome he could probably be friends with anyone. I’ve seen him navigate crosscultural spaces without denying his ethnic self and share stories about his ethnic heritage in rooms that are mostly non-Korean. James tells his real stories. He knows his ethnicity is valuable and shares from his life in ways that connect with people even if they are not Korean. Once he said, “Too often, Asian Americans define ourselves by our weaknesses and faults. It’s time we started to define ourselves by our strengths and beauty.” As he reflects on what he is learning and how he is navigating crosscultural spaces, I learn from his experiences. James helped me see how I could be a Korean American, Christian, female leader.

As we draw from the rich experiences of mentors and friends and intentionally learn the skills needed to become ethnically aware, we become more hospitable members of the multiethnic family of God. Ethnicity-aware living allows us to become more hospitable to those close and far from God as we enter into different settings and learn more about people. Ethnicity-aware living helps build trust so that a non-Christian of a different ethnic background can trust us both as a Christian and as someone who is ethnically different.

SKILLS FOR COMMUNICATING IN GROUPS

As our social, work, and church circles become increasingly more diverse, here are some starter tips for communicating in diverse groups.

Look up, speak second. I went on a summer missions trip with a group of white and Asian American women and men. When our group was asked a question during orientation, I noticed that the white participants would look up and immediately start sharing. The Asian American participants would first look around to see if they were going to cut anyone off as they answered. This led to the persistent cutting off of the Asian American members by the white members. Both were trying to participate the way they knew best: the former by offering their ideas and opinions and the latter by making space for others to share. When I pointed this out, the group was surprised! So we implemented a general principle of “look up, speak second,” which allowed more people to join the discussions, including our Ugandan team members that would join us later in Kampala.

Use numbers to gauge the strength of opinions. Saying something such as, “Why don’t we do this?” can sound either like a suggestion or a strong conviction, based on the hearer. When supervising Asian American men and women, I have to be careful that I’m clear in my communication. Because the Asian American culture is a high-power distance culture, they are likely to do what I tell them (or figure out a way to go around me). So if I’m stating an idea, I usually say, “I think we should do this for our community event. I’m a three out of ten.” If I’m stating a strong opinion, I say instead, “I think we should do this for our community event. I’m a nine out of ten.” Using a statement plus a number scale invites the more indirect or hesitant members of your group to share their insights and lets you hear ideas from a broader range of people.

Gathering input: “fist to five.” In conversation, the loudest and most opinionated voice can be overruling. However, the repeat pattern of the most dominant personality determining group decisions can feel oppressive, limiting, and inhospitable. If you’re making a group decision about something, whether it’s as small as where to go eat or as big as making ministry structural changes, you need to get input beyond the loudest voice. Avoid the assumption that silence means agreement or consensus. I have been in many settings where ethnic minorities or women do not speak up much, and it’s often construed as agreement versus something else (silent disagreement, fear of presenting a dissenting opinion, or an internal, silencing voice of self-critique). Try this instead: let’s say your group is making a decision, and you want to gauge the actual ownership of the decision from everyone. Ask, “On a scale of zero to five, how comfortable do you feel with our decision? Please show via your fingers (a fist meaning zero, or very uncomfortable; five fingers meaning five, or very comfortable).” Ask them to show their votes all at the same time (“Vote on the count of three”) so they don’t feel pressured by others’ opinions on display.

If the group shows mostly fours and fives, the group is on the same page. If the group shows mostly fours and fives but there are one or two outliers that show lower numbers, pause and (respectfully) ask them why they feel that way. When the dissenting voices are of the ethnic minority in the group, this method helps pinpoint where crosscultural differences might be getting in the way of making a decision.

Doing “fist to five” allows you to identify opinions that might otherwise be silent. Seeing an individual or a whole group show twos and threes might hurt, but then you get to ask the next question: “What would it take to make it a five?” or “What it would it take from each of us to make it a five?” Especially in teams that are committed to a common objective, this allows people to not just focus on the gap but also to contribute ideas and cultural influences.

Vary group discussion. If you’re used to leading in a way that invites the most expressive and uninhibited people to speak up, try to vary your leadership technique. Break people off into small groups (pairs or triads) and have them share with each other. Ask them to appoint a spokesperson to share on behalf of their group.

In one meeting, my friend Larry tried to encourage more sharing from men and women of color by asking the white men and women in the room to wait until others had spoken. I predicted what happened next: “Did most of the black men and women speak up but not many Asian Americans?” I asked. “Yes! How did you know?” he responded. Larry was using freeform discussion in the large group. Instead, he should have broken people into triads and asked them to appoint spokespersons. This allows for the ethnic diversity of the spokespersons to broaden and for more people to engage in dialogue. When a non-Christian in a group is the spokesperson, it affirms their seeking and can help deepen their understanding of Scripture.

Another way to encourage discussion is to go around in a circle or start with the youngest or the eldest in the room (depending on which age demographic may end up being the least heard). And every ethnic background has reflective thinkers that need time to process their thoughts internally before sharing them. I remember leading a Bible study with a non-Christian who asked after a couple meetings, “Could you email us the questions beforehand? It helps me to have more time to think.”

SKILLS FOR BUILDING TRUST IN A MULTIETHNIC COMMUNITY

Multiethnic community involves extending hospitality across cultural differences. It also involves being aware of racial history and context while honoring the other. Here are some things that you can do to help build trust in a multiracial, multiethnic community.

Use a prophetic instead of an accusatory voice. Everyone is a learner, and that means that everyone is going to make mistakes as they interact in multiethnic community. If you define someone by only their mistakes, you are telling them that they themselves are that mistake.

We must choose to be prophetic instead of accusatory. An accusatory voice says, “Look at this thing you did wrong! You are wrong!” It uses shame, fear, and anxiety to motivate change. It promotes self-protection and is usually unsuccessful in the long run. A prophetic voice says, “This is not who God is calling you to be. You could be so much more than this broken behavior. Come and follow Jesus into that hope.”

As we teach each other to be in multiethnic community, and particularly as white Americans are taught to be in multiethnic community, it’s important to affirm a positive identity and maintain a vision of what could be, instead of naming the person by their unintentional (or sometimes intentional) mistake only. Saying, “You’re a racist because you said this racist comment,” will bring up denial or extreme apology. It doesn’t help the person change for better. Instead, saying, “I know you care about loving your community, and that you’re more than that comment; it hurts in this way: _________. How can it be different next time?” points to change and the person that could be.

My husband experienced this as a child in rural New Jersey, when an elderly white woman in his neighborhood called him Oriental. He gently corrected her by saying, “I’m sorry to interrupt, but I wanted to let you know that Oriental is not the correct way to refer to my people. You should call us Asian. Oriental refers to furniture, and it’s an offensive label because it was originally a term meant to describe Asians as unwanted ‘others’ from a foreign place. Could you use Asian in the future?”

The woman was genuinely surprised because no one had ever corrected her, and Oriental had been an accepted term in her white community for some sixty years. “Thank you for telling me! I would never have known,” was her response. She always made it a point to use the word Asian instead of Oriental in future conversations with him.

What would happen if every time you heard a person (white or nonwhite) make a mistake or say something offensive, you didn’t talk about what they did wrong and instead focused on what could be? Instead of failures, you would see students, people who could learn with you. Cultural learning is not a trophy to be waved around like a flag or bragging rights. It’s something that’s meant to be shared. And this is not just a specific task for white folks. We all need to learn about what it means to be in a multiethnic community.

If you’re starting this journey from zero, embrace that reality instead of being ashamed of it. Debrief your experiences with a safe person, someone who is willing to teach you and give feedback about your interactions with them and others in a multiethnic community. This kind of invitation builds far more trust than trying to be perfect on your own (which actually isn’t possible). Perfection is never something the Lord demanded of us. Faithfulness and perseverance are the only requirements. Ask Jesus for the courage to learn, and find some trustworthy people to help you grow.

Talk about an ethnically inclusive God and his story. As we share the good news and reflect upon the story of God, it’s important to use a variety of images to represent God. Much imagery of Jesus casts him as a blond, blue-eyed white man carrying a lamb. However, Jesus was Middle Eastern and probably looked Palestinian! If we continue the practice of showing Jesus as white, we fall into the idolatry of prizing whiteness above others. God created us in ethnic diversity—no one culture captures his goodness or character perfectly. Try to vary the images you use so that you don’t communicate that God is a god of white people only or that you need to be white in order to be included in the kingdom of God. Representing Jesus as white is not bad. Just make sure you don’t emphasize a bias toward whiteness and instead include white as one of many options.

My mother has a book by a Korean artist that includes drawings of the gospel of Matthew. Every scene, from Bethlehem to Calvary, depicts Jesus as ethnically Korean because the artist wanted to make the gospel more accessible to his people. Likewise, in your stories and sermon illustrations, make sure the protagonist is not always one ethnicity. In particular, be careful about always depicting white people as the heroes while black and brown people are the villains. Use stories with heroes from a variety of ethnicities.

In your signage and visual media, include people of every ethnicity—and I don’t just mean six white people and one black person, which is visual tokenism. Small things go a long way to communicate intentionality and hospitality to people of color. On the flip side, there are majority black and Asian churches that intentionally try to communicate welcome to white and nonwhite people that are the minority in their community by using photos and stories that include them in their communal life. Communicate who you desire to be.

If you’re a ministry leader preparing a sermon or a study, seek to learn from and be influenced by teachings from more than one ethnic group (particularly if the group has previously heard from primarily white men). Reflect the diversity of the church in the United States and globally in your quotes and references to theologians and Christian examples.

Honor and be tender toward the formerly dishonored parts. When Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 12:23, “The parts [of the body] that we think are less honorable we treat with special honor,” he was well aware that he was speaking to a diverse Corinthian church, full of Jews and Gentiles, slaves and free. In the Roman Empire, the most dishonored population would likely have been the poor, unskilled slaves. In the United States, we have a sad history of people of color being dishonored through systemic racism and prejudice, and we need to recognize that.

Many white Americans that come from low-power distance families don’t like being called “sir” or “ma’am” because they don’t want to be reminded of their advancing age. But for many people of color and immigrant cultures that place value in age-based social hierarchy, “sir” or “ma’am” honors the older people’s status as elders. Given that much of American history has dishonored black men and women, I say “sir” and “ma’am” to convey respect toward black elders that I meet. Though I am Asian American (not white), I represent people who have either had negative interactions with black Americans, avoided them, or stereotyped them according to negative media projections.

Honoring is different from reinforcing tropes or stereotypes. Honoring says, “You are of great value to God and therefore to me.” In big and small gestures, honoring the other affirms them as being made in the image of God. So whether it’s greeting with respect an elder whose ethnicity is different from your own or extending hospitality toward an ethnic other, do so knowing that you are extending shalom across a history of racial scars and division.

Meet guests in their sadness about ethnic pain or injustice. Sometimes the guests at your table will bring stories of sadness or pain, particularly as it relates to their ethnic people. And if your hospitality is truly about hosting them well and not just about having a nice diverse experience, you will host them in their sadness. Daisy is a Harvard Divinity School student, a Latina from California. She was born in Mexico but grew up in the United States undocumented. We invited her and her boyfriend, Frank, to dinner after church, along with a group of white people they didn’t know. When Daisy was asked how she was doing, she answered that she was sad. She recently took a trip to Arizona to understand the policies and procedures regarding the capture of undocumented immigrants, most of whom were Latin American. She talked about how many people cross the desert and die of dehydration, how Native American reservation communities report undocumented immigrants because they don’t want police raids in their community (though others leave water jugs to help such travelers), and about how the immigrants get sent to prison and then undergo expedited removal back to the land from which they were trying to escape.

My husband and the white friends at dinner didn’t know what to say other than, “We know so little about this. Thank you for sharing with us.” We felt the heaviness of Daisy’s sorrow. And for Daisy, it was a gift to share with a group of Asian and white strangers-turned-friends who were willing to listen. It made us want to learn more and understand the complexity of issues surrounding immigration. It built trust between Daisy, Frank, and my white friends because we didn’t run away or change the subject. We were communicating that they were welcome at the table just as they were, in their beauty and scars.

Shortly after the shooting death of black teenager Michael Brown by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, that led to community unrest, I reached out to John, a black man who is a member of our mostly Asian and white church. “How are you doing with everything happening with Ferguson? How can our church be praying for you?” John’s eyes welled up with tears as he said, “It just means so much that you would ask.” During a prayer vigil, my husband and I wept alongside of John as he shared about the painful conversations he would need to have with his soon-to-be teenage son and the fears he had for his son’s safety. John and I are in different life stages, different ethnic groups, and entirely different realms of work. But because my husband and I were willing to listen, sit with, and pray with John, it cemented a depth of trust between us.

We can’t avoid the sadness and pain that our brothers and sisters of different backgrounds face navigating a racially and ethnically broken world. My husband and I sit with white friends who weep and wrestle with difficult experiences, times when they messed up or were misunderstood as white women and men. We make space for Latino friends to share their struggles. We give space to friends who need to grieve on their own or with their people before they are ready to talk. Hospitality is about creating a home where you can be safe, cared for, and loved by your spiritual family without having to pretend like everything is okay.

QUESTIONS FOR INDIVIDUAL REFLECTION AND SMALL GROUP DISCUSSION

-

1.Name a time where you felt like a fish out of water in a cultural context that was different than your own. What was that like for you? What happened? What would you do differently next time?

-

2.What are some crosscultural communication skills and habits that you could try out in the future? What questions do you have?

-

3.Who are the Christian authors and theologians who influence you the most? What do you notice about their ethnic backgrounds?

-

4.Who are some mentors and cultural interpreters that can help you navigate multiethnic community?

RECOMMENDING READING

Cross-Cultural Connections: Stepping Out and Fitting In Around the World by Duane Elmer

Crossing Cultures with Jesus: Sharing Good News with Sensitivity and Grace by Katie J. Rawson

Crossing Cultures in Scripture: Biblical Principles for Mission Practice by Marvin J. Newell