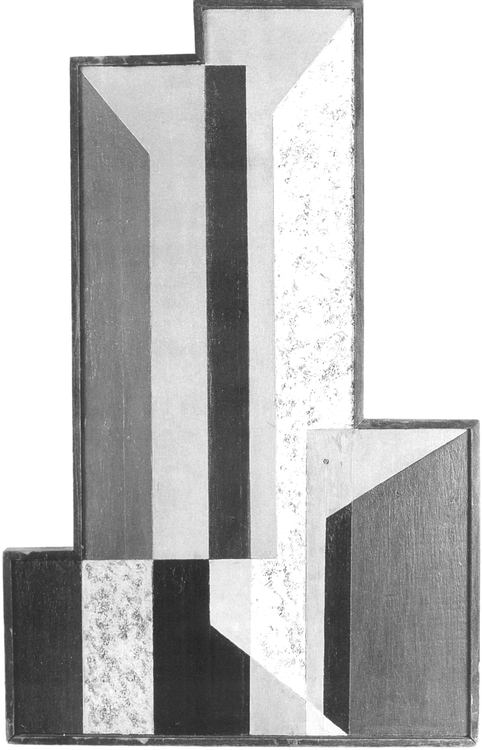

Fig. 32 Charles G. Shaw Polygon 1936

by Leah Rosenblatt

Fig. 32 Charles G. Shaw Polygon 1936

Charles Green Shaw (1892—1974) came of age during the fast-paced, consumer-driven swing age of the Roaring Twenties. Born in 1892 to a wealthy New York family, he lived the capricious life expected of a New York socialite, despite losing both his parents at a young age. Beneficiary to an inheritance based in part upon the Woolworth fortune, Shaw summered in Newport and spent Christmas at Mrs. W. K. Vanderbilt's balls, consorting with the well-bred, well-groomed, and well-moneyed folk of New York's elite.

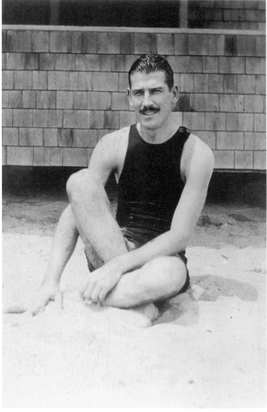

In 1914 Shaw (fig. 33) graduated from Yale College. He subsequently spent a year at Columbia University's School of Architecture and then set out to attain a professional position to equal his prominent social and physical stature (he was a lithe 6 feet 2 inches tall, which earned him the nickname "Big Boy" from his small friend Cole Porter). Like many of his compatriots, he was briefly deterred from his path by serving in World War I, but he was lucky enough never to have seen active duty, remaining a supply officer in England. At the war's end he made an unsuccessful attempt to follow in the family footsteps and become a businessman. Immediately afterwards Shaw met with his first professional success—as a writer. During the following decade, Shaw recorded his own reverent approvals and glib dismissals of the colorful social crowd to which he belonged, contributing articles to magazines such as Vanity Fair, the Smart Set, and the New Yorker, among others.1 These credentials, along with his social pedigree, brought him into contact with some of the most famous figures of the time, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, H. L. Mencken, Sinclair Lewis, George Gershwin, and the American artist George Luks.

Fig. 33 Charles Green Shaw on the Beach at Newport, R. I. ca. 1912

Shaw's introduction to Luks evidently helped inspire him to paint. Although he claims to have studied privately under Luks at this time, no evidence has been found to support this. Nevertheless, as Shaw notes in his journals, his interest in painting and studying art in Paris (where he would first visit in the early 1930s) did coincide with his interviews with Luks.2 Until that time, Shaw's only interest in art manifested itself in the form of illustrations—caricatures and line drawings—that he made for his articles. He did not yet have any formal art training.

As the roar of the twenties quieted to a hum and times of great economic struggle set in, Shaw sensed that witty commentary about New York socialites was no longer appropriate. Slowly he turned away from writing to focus on developing his techniques as a painter. In 1928 he enrolled in Thomas Hart Benton's life class at the Art Students League,3 and at the turn of the decade he traveled to Europe twice: in 1929—30 and 1931—32. The latter trip proved to be extremely influential, and by the time he returned to New York in 1932 Shaw considered himself a painter.4

Despite his penchant for commentary about the lives and work of others, Shaw rarely discussed his personal development as a painter. He diligently kept a journal for over sixty years and wrote novels, children's books, and poetry, as well as magazine articles and interviews, but the only self-reflective work he published was a four-paragraph, one-page article entitled "The Plastic Polygon." The article appeared in a 1938 issue of Plastique5 and provides a lucid explanation of Shaw's most technically and professionally significant works.

As he reveals in this essay, Shaw used the term "plastic polygon" to refer to a format based on "a several-sided figure divided into a broken pattern of rectangles" that he developed from the Manhattan skyline in the mid-1930s. In creating these works he gradually reduced the subject's structures to a system of elegant vertical and horizontal lines (figs. 8, 32, and 34). Shaw commented on the resulting reduction from three dimensions to two, noting that "Distance had yielded to design; depth had surrendered to a wall of equal planes. For what it had acquired in purity, it had wholly lost in three-dimensional value." Ultimately, the plastic polygon, "sprouting, so to speak, from the steel and concrete of New York City,"6 garnered a positive critical response and provided Shaw with a distinct abstract formal language that rendered these paintings more than mere copies of their abstract European counterparts. Against a current of public dialogue to the contrary, these works spoke of the viability of an American abstract art.

As early as 1934 Shaw mounted his first solo exhibition at the Valentine Gallery. The following year Albert Eugene Gallatin included works by Shaw in an unprecedented solo exhibition at his Gallery of Living Art, spurred by his belief that "Mr. Shaw is doing some of the most important work in abstract painting in America today."7 In 1936 Shaw participated in the momentous Five Concretionists show curated by Gallatin at the Reinhardt Galleries, which also included works by George L. K. Morris, John Ferren, Charles Biederman, and Alexander Calder. By the early 1930s Shaw had already met Morris and Gallatin, with whom he shared a similar socioeconomic background and a common interest in abstract art. The three were also joined by their conviction that it was essential to provide public support for American abstract art, particularly because the current climate was highly critical of it. Major cultural institutions like the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art were either more interested in European abstraction or saw contemporary American abstract art as second rate. It is probably no coincidence, then, that the Five Concretwnists show of American abstract artists opened at the same time as Alfred Barr's landmark exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art at the Museum of Modern Art. The show was criticized (as was Barr) by Shaw and his colleagues for being both Eurocentric and retrograde.

In response to attitudes like Barr's and to increase their exhibition opportunities, the following year

Fig. 34 Charles G. Shaw Untitled 1937

Shaw, Morris, and Gallatin, along with Morris's new wife Suzy Frelinghuysen, joined the American Abstract Artists group. Though the organization was originally formed to increase exhibition opportunities for American abstractionists, it would soon prove to be a significant force in bringing issues associated with abstract art directly to the American public.

Shaw provided his most outspoken defense of abstract art in the 1938 American Abstract Artists' yearbook. In the opening essay, entitled "A Word to the Objector," Shaw typically does not address his own work as a painter but instead focuses his attention outward, to the general state of abstract art and those critical of it. He denounces these critics as having a "more or less conventional turn of mind." In his characteristically glib (and somewhat derogatory) manner, Shaw states in his conclusion:

One seeks, for example, rhythm, composition, spacial [sic] organization, design, progression of color and many, many other qualities in any aesthetic work. Indeed it is the perfection of these very qualities that constitutes an aesthetic work and there is surely no earthly reason why a painting may not possess all such qualities and still be the most abstract picture ever painted. Art, since its inception, has never depended upon realism. Why, one cannot help wondering, should it begin now? Art, on the contrary, is (has been, and always will be) an appeal to one's aesthetic emotion and to one's aesthetic emotion alone; not for the fraction of a split second to those vastly more familiar emotions, which are a mixture of sentimentality, prettiness, anecdote, and melodrama.8

Despite this impassioned voice, Shaw never became as publicly involved in the crusade to defend abstract art as his friend Morris. Nevertheless, Shaw's persistence as an abstract painter throughout the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s bespeaks a similar fervor, if of a more private nature. Indeed, his paintings did progress beyond the plastic polygons of the 1930s. His biomorphic wood reliefs (fig. 35) gave way to more richly and freely painted canvases. His lyric and rhythmic forms of the 1950s and 1960s clearly develop out of the works that precede them. In his last works, Shaw consciously returned to a strict and pure geometric form of abstract painting, one more consistent with the Minimalist aesthetic of the 1960s.

Paradoxically, Shaw was a prolific writer and critic of others who, to quote his friend Morris, "declined ever to talk about himself,"9 Thus it is his visual work itself that must inform us about his painterly inclinations and philosophies. Shaw's abstract visions, be they organic or geometric, graphic or lyric, are cast in a unique language that typified all of his works, emphasizing his fundamental interest in form. Regarding this he once remarked, "one of the major issues I had in mind was form. The form of the thing, whether it was a poem or a piece of prose or a piece of painting."10

1. A compilation of these interviews was published in 1928 under the title The Low-Down (New York: Henry Holt and Co.).

2. See Buck Pennington, "The 'Floating World' in the Twenties: The Jazz Age and Charles Green Shaw," Archives of American Art Journal 20, no. 4 (1980), 17-24, which surveys Shaw's papers in the Archives of American Art.

3. Ironically, it was against Thomas Hart Benton and his school of Social Realism that Shaw and his abstract painter colleagues fought so hard to legitimize themselves during the following decade. Social Realism was an extremely popular, readable, arid "non-subversive" form of painting that seemed to glorify an "Americanness" that abstract art was viewed as dismissing.

4. Pennington, 22.

5. Charles Shaw, "The Plastic Polygon," Plastique, no. 3 (Spring 1938), 28. Reprinted in this volume.

6. Ibid.

7. "Charles G. Shaw Has One Man Exhibition at New York University's Gallery of Living Art," New York University press release, April 27, 1935, quoted in Pennington, 22.

8. Charles G. Shaw, "A Word to the Objector," 1938 AAA Yearbook (New York: Privately published).

9. George L. K. Morris, "Charles Green Shaw," The Century Yearbook: 1975 (New York: Century Association, 1975), 281.

10. Charles Shaw, interview with Paul Cummings, April 15,1968,21, Charles G. Shaw Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.