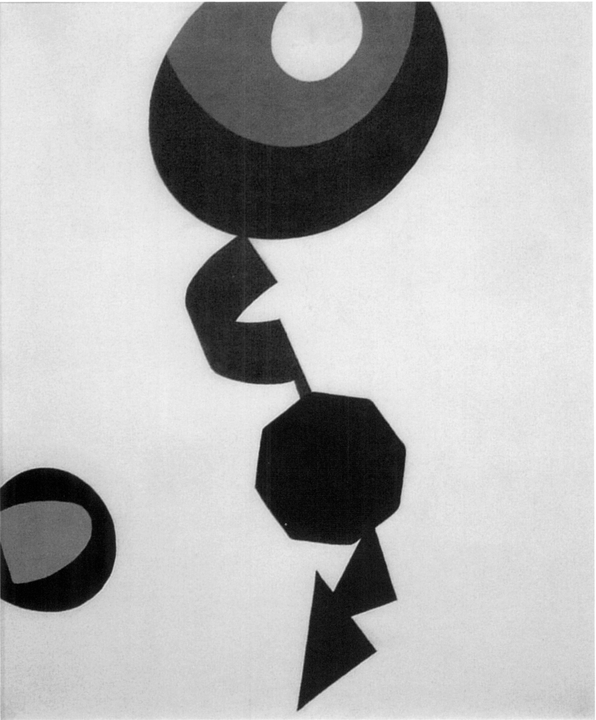

Fig. 22 Albert Eugene Gallatin Composition No. 57, February 1949 1949

by Gregory Galligan

In the early months of 1936, approaching the tenth anniversary of his public collection, the Gallery of Living Art, Albert Eugene Gallatin took up his own palette. In fact Gallatin had already tried his hand at painting a decade earlier, about 1926, after studying briefly with Robert Henri,1 whose book, The Art Spirit, had been published in Philadelphia in 1923. Cloaked in practical studio maxims, the creative fervor of this American master doubtless appealed to Gallatin, whose own outwardly staid yet febrile aesthetic had previously been fired by Art Nouveau prints (by Aubrey Beardsley and others) and by the work of James McNeill Whistler.

At the time he met Henri, Gallatin was also well versed in the new formalism of Roger Fry and Clive Bell, as well as the burgeoning literature of the studio method book, as, for example, Denman W. Ross's A Theory of Pure Design: Harmony, Balance, Rhythm, of 1907 (Fry himself had cited Ross in his popular Vision and Design of 1920).2 Despite this preparation, Gallatin's first foray into painting (as evidenced in a handful of surviving realist and semi-abstract canvases) turned out to be a fleeting one, due to the demands of managing his public collection. Not until 1936 would Gallatin return to the studio—even as his collecting of modern masters, at that moment, was hardly slackening, indeed, before the year was out Gallatin had acquired Picasso's widely coveted Three Musicians, 1921, and Fernand Léger's seminal La Ville, 1919, as well as first-rate canvases by Georges Braque (The Cup, 1917—18) and Albert Gleizes (Composition, 1922), all now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In retrospect, these acquisitions collectively constitute a summa theologiae of Gallatin's close study of Cubist pictures over a period stretching from 1923, when he first met Picasso, to 1936, after which Gallatin would shift his attention to the work of his American colleagues—principally fellow members of the American Abstract Artists association—and others working in decidedly "constructivist" modes, such as Cesar Domela, Naum Gabo, and Kurt Schwitters.3

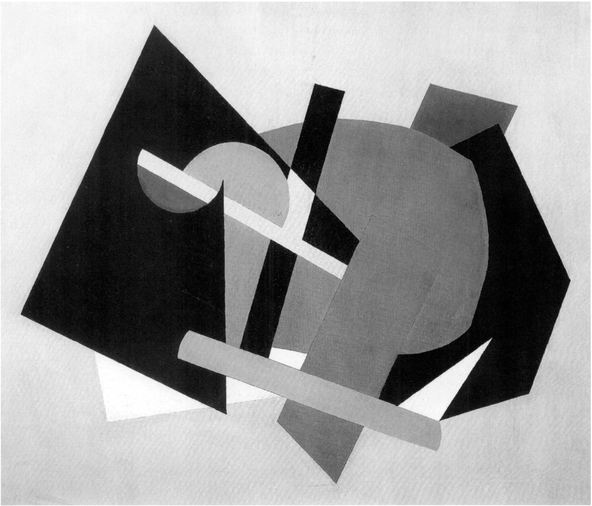

Gallatin's painting (figs. 19, 20, 21, 22, and 23) thus mirrors his initial immersion in Synthetic Cubism, as well as his subsequent fascination with international Constructivism. This is evident in Gallatin's Composition No. 70, 1944—49 (fig. 24), an abstract thicket of somber blacks, blues, and grays, enlivened only by an underlying white field and an inverted half-moon of vermilion. Gallatin often favored black, brown, green, gray, and blue (sometimes along with yellow or beige) in abstract compositions marked by episodic passages of sharply contrasting color, not unlike a blazing necktie set off by a houndstooth suit. The paradigm for this earthy, autumnal palette may have been provided, if only unconsciously, by Gallatin's own finely tailored wardrobe. As though to suggest a symbiosis between abstract painting and handsome textiles, Gallatin was prone to

41 speak of the picture plane as a "woven" field when enumerating its non-illusionistic qualities.4

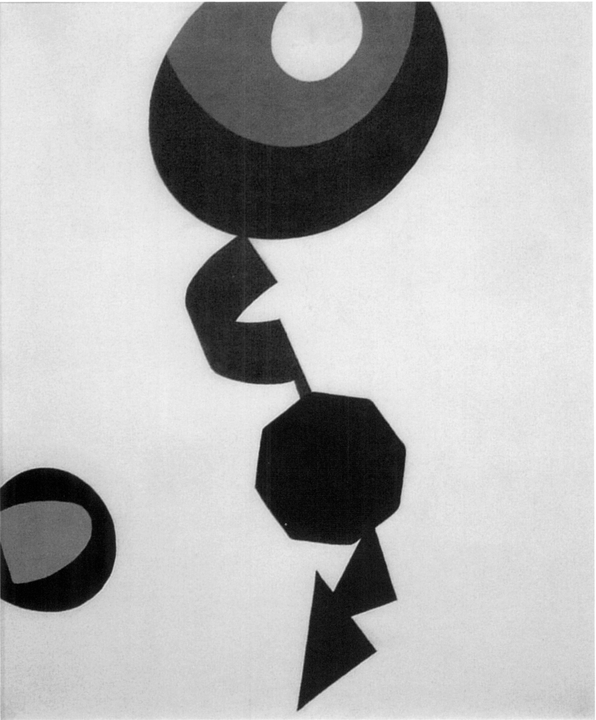

Numerous passages in such "compositions" (a title that recurs in much of his work of the 1930s) display Gallatin's familiarity with the formal inventions of papier collé (pl. ix), prime examples of which he avidly collected, such as Braque's Le Courrier (Newspaper, Bottle, Packet of Tobacco), 1914 (Philadelphia Museum of Art). In keeping with his regard for Cubism as the apex of a long-standing international, classical tradition, Gallatin's own abstractions often took shape as careful studies after such modern masterpieces. While his models might sport representational features, such as Braque's newspaper, Gallatin would "strip down" (as he frequently said) such signs to wholly non-objective planes of solid color in a stringent process of formal distillation—even as the dynamic yet poised play of Gallatin's abstract forms ultimately derived from a closely observed still life or other such studio-based object.

Gallatin's reduction of visual phenomena to abstract designs reflects his admiration for the work of Juan Gris, whom Gallatin revered as "the noble and profound master of Cubism,"5 Perhaps most indicative of this appreciation for Gris is Gallatin's shuttling, throughout the 1940s, between nonobjective, or wholly invented compositions, and more representational, or "found" modes of pictorial conception. For instance, Kenilworth Castle No. 2, 1940 (pl. x), evokes, in shorthand, a modernist tradition of abstract landscape painting that stretches back to Picasso and Braque's proto-Cubist works of 1908 and 1909. That said, Gallatin's canvas points to the strong influence of design culture on American abstract painting during the late 1930s, which now mediates the process of transposing an observed subject to an abstract composition. This is where Gallatin approaches the aesthetic of Gris, whose work achieves a conceptual equipoise between representation and pure abstraction, as in Gris's Still Life (The Table), 1914 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), which Gallatin acquired in 1932. Here flat planes arise from natural forms only to assume a wholly non-objective, if not quasi-decorative, order.

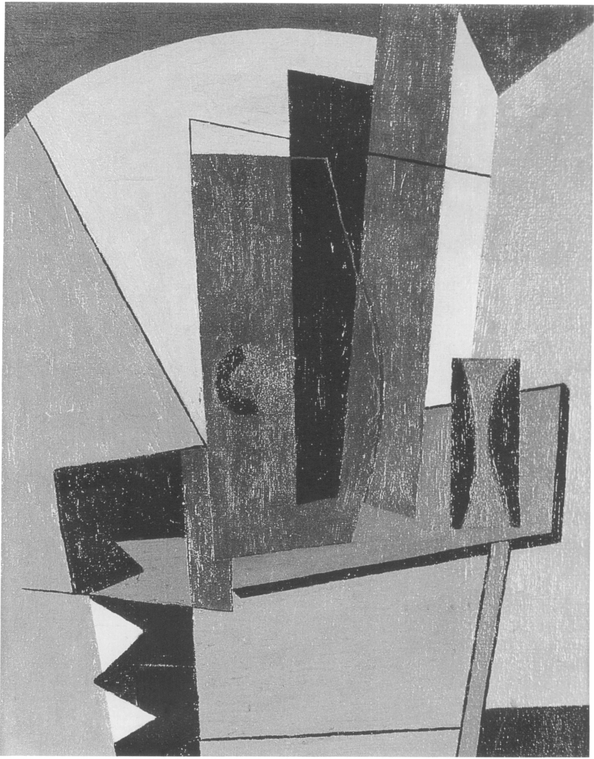

Despite Kenilworth Castle's sharply angular, accordion-like contours, this picture's indeterminate syntax also reflects that of Gallatin's colleague (and acquisitions consultant) Jean Hélion. By the early 1930s, Hélion—a founding member of the Paris-based group Abstraction-Création—had perfected an idiom of husk-like forms hovering before a nearly monochromatic field and clustered so as to evoke rolling contours of landscape or the human body, as in his Composition of 1934 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), which Gallatin acquired that same year. Hélion's modeling with light and shadow, and his disposing of forms in quasi-mechanical array across the picture field, recall the wide influence of Fernand Léger at this moment in both Paris and New York. Gallatin was no exception to this trend, proudly claiming Léger as one of the "cornerstones" of his collection. This sentiment was reflected in a number of Gallatin's abstractions ot the late 1930s, such as Composition|Mural of 1937 (Brooklyn Museum of Art), which clearly take Léger's non-objective canvases of the previous decade as their point of departure.

By the mid-1940s Gallatin had become a hearty enthusiast of international Constructivism. This is evident in his wholly non-objective Forms and Red, 1949 (pl. xi). An abbreviated formal drama haunts this picture, in which two ebony-violet disks seem to exchange a red shard across a milky field. This quality of suspended animation among abstract forms betrays Gallatin's eye for the work of El Lissitzky and László Moholy-Nagy. It is all but certain, for instance, that Gallatin attended the grand memorial

Fig. 22 Albert Eugene Gallatin Composition No. 57, February 1949 1949

Fig. 23 Albert Eugene Gallatin Untitled 1943—45

Fig. 24 Albert Eugene Gallatin Composition No. 70 1944—49

exhibition of works by Moholy-Nagy that was mounted by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation in the summer of 1947.6 Gallatin's interest in the work of Moholy-Nagy is suggested by the shared abstract syntax of Forms and Red with certain of Moholy-Nagy's watercolors of the late 1920s, as well as his later non-objective works in oil on plexiglass, with which Gallatin would have been familiar by the end of the decade.7

The reductivist idiom of Forms ana Red also bears affinity to that of Alexander Calder's Construction of 1932 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), which Gallatin purchased in 1934. Gallatin referred to such works as "concretions," in an attempt to convey their assertive materiality and lack of representational content. He appropriated the term from Theo Van Doesburg, who, shortly before his death in 1931, had established the exhibition society Art Concret in association with Hélion (who, as earlier noted, was to become an indispensable member of Gallatin's own circle).

It was, however, the Synthetic Cubist legacy of Picasso, Braque, Gris, and Léger that would figure most decisively in Gallatin's work as vanguard collector and painter alike. As though to boast of this influence, Gallatin cobbled together a homage to Picasso from an empty cigar box in 1939. Parroting Picasso's musical troupe on its cover (in condensed format), Gallatin's Cigar Box after "The Three Musicians" (Philadelphia Museum of Art), its lid propped open like that of a grand piano (as though to restore a missing instrument to Picasso's ensemble), harbors a wan, non-objective painting in oil and gouache along its interior bottom surface. Cradled within this Cubist casket, the painting's languorous curves speak of Gallatin's lifelong respect for the work of Jean Arp and Joan Miró. Such debts duly cited, an entire second history of Cubism, as prime source and recast idiom for an American vanguard, is contained in this slim volume. At his best, Gallatin thus coaxes from curt geometries the complex spirit of American abstract painting of the interwar period.

1. George L. K. Morris attested that Gallatin studied with Henri in the early 1920s; see Gail Stavitsky, "The Development, Institutionalization, and Impact of the A. E. Gallatin Collection of Modern Art," Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1990, 1: 79, n. 278.

2. Fry's book and Clive Bell's widely influential Art of 1914 were both in Gallatin's personal library; see Stavitsky, 3: Appendixes B and F, n.p.

3. Gallatin's acquiring, in 1936, of Domela's Construction of 1929 and Schwitters's Men Konstruction of 1921 also signifies this shift from a Cubist to a Constructivist aesthetic.

4. In an interview in 1943, Gallatin referred to textile design as an appropriate practical outlet for modern art; see Rosamund Frost, "Living Art Walks and Talks," Art News 42 (February 15, 1943), 14, 27—28.

5. See Albert Gallatin, "The Plan of the Museum of Living Art," Museum of Living Art, A. E. Gallatin Collection (New York: New York University, 1940), n.p.

6. See In Memoriam LdszU Moholy-Nagy, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Non-Objective Painting, 1947).

7. Such work was also illustrated, albeit diminutively, in Moholy-Nagy's pedagogical text, The New Vision, which was published in English translation in 1928 and reissued in a revised edition in New York in 1947; see László Moholy-Nagy, The New Vision and Abstract of an Artist, ed. Robert Motherwell, 4th rev. (New York: George Wittenborn, 1947), 83.