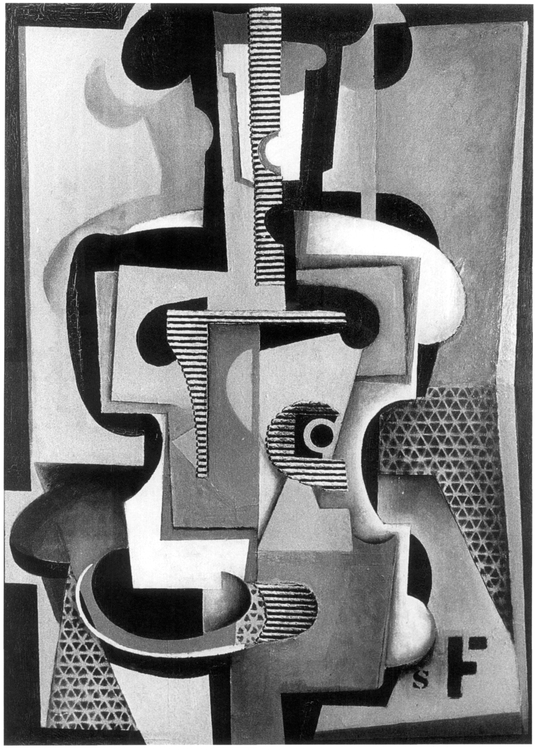

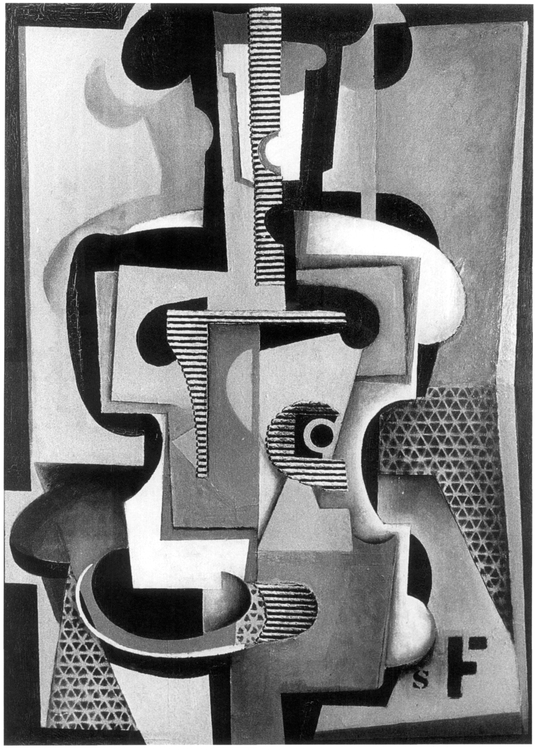

Fig. 31 Suzy Frelinghuysen Composition 1944

by Allison Unruh

Fig. 31 Suzy Frelinghuysen Composition 1944

Suzy Frelinghuysen enjoyed a unique artistic career, distinguishing herself both onstage and in painting. Born into a socially prominent New Jersey family, she was raised amidst affluence that enabled her to pursue her artistic passions, studying painting and singing from a young age. Following her marriage to artist and critic George L. K. Morris in 1935, Frelinghuysen began experimenting with abstract painting, which she quickly mastered and imbued with a distinctive sense of tactility and color. Although she considered herself foremost an opera singer (perhaps in part to distinguish herself from her husband's artistic identity), Frelinghuysen also found success in the visual arts, taking part in many exhibitions and attracting favorable criticism at a time when abstract artists in the U.S. were struggling for recognition. Frelinghuysen felt that her dual artistic identities were complementary, however, describing how "one is a good balance for the other. Painting is so contemplative while singing is so personal."1

Frelinghuysen's Cubist paintings are characterized by tension between the simplification of forms into flat planes and the elaboration of their textures and plasticity. Her subjects are never fully abstract, since she believed that "most art comes from nature."2 She often employed collage elements referring to the Cubist masters (particularly Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris) she and Morris admired, utilizing ephemera from her daily life. In particular, the frequent appearance of scraps of sheet music refers to her celebrated opera career.

Printemps, 1938 (pl. viii), demonstrates how quickly Frelinghuysen became fluent in a Synthetic Cubist language, having only begun to paint in an abstract manner in the late 1930s. Previously, Frelinghuysen had worked in a realistic mode, and elements of this earlier style may be seen in her painterly brushwork and in the vestiges of spatial illusionism. She deftly layers collage elements with passages of paint to represent a café still life: a wine glass and bottle accompanied by fragments of Plastique, the avant-garde art and literary journal. The word Printemps (French for "spring") refers to the spring 1938 issue of the magazine. Morris, along with Gallatin, Jean Arp, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, had founded Plastique in the hopes of forging international connections among abstract artists. The magazine cover in Frelinghuysen's painting superimposes on the French title the English translation Plastic, framing Frelinghuysen's artistic practice in a Franco-American aesthetic dialogue. Her palette echoes the colors of the magazine's cover, while the sunny yellow and sky blue also evoke a vernal Parisian atmosphere. Such bold colors characterize much of her work, where tension between cool and warmer tones often builds a painterly sense of depth. The stenciled latticework pattern seen here, a piece of metal radiator grid that she found in her studio, reappears in many later paintings; here it evidently signifies woven chairs, according with the café theme. Yet her choice of this pattern also refers to Picasso's use of faux-caning patterns, as in Still Life with Chair Caning, 1912 (Musée Picasso, Paris), his first collage.

Composition, 1943 (pl. xiii), is one of Frelinghuysen's most abstract works from this period, yet it still maintains her characteristic figural references. Here she alludes to the human form: the white polygon at top suggests a head, and the triangular forms below, a torso. She produced stylized variations on this painting in other compositions, such as Man in Café (pl. xiv) and Composition (fig. 31), both of 1944, all of which form an extended dialogue with works such as Juan Gris's sculpture Harlequin, 1917 (Philadelphia Museum of Art], which was then in Gallatin's collection. The central blue-gray form with a circular accent also relates to Gris's Still Life with Guitar, 1917 (Frelinghuysen Morris House and Studio), then in the Morris-Frelinghuysen collection, and may represent an abstraction of the guitar held by Gris's figure. Frelinghuysen's palette is a distinctive blend of gray, rose, and blue tones, whose modulations of color provide a dramatic contrast to the solid black forms. The integration of corrugated cardboard is characteristic of her works from this period. Derived from Cubist collages by Braque and Picasso, the horizontal stripes of the cardboard often signify shading, alluding to the convention of cross-hatching in drawing. Painted over to emphasize the shadows cast by its undulating texture, the machine-made material provides a sharp contrast to the elegantly mottled brushwork. Frelinghuysen's work in collage was well respected; she was included in Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century Collage exhibition of 1943, where collages by American artists (including Morris, Gallatin, Jackson Pollock, and Robert Motherwell) were displayed alongside those by established Europeans (including Braque, Gris, Jean Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, and Joan Miró).

Still Life, 1944 (pl. xii), demonstrates Frelinghuysen's continuation of the style she developed in the late 1930s. It represents an elaboration of the compositional themes and structure of Printemps, horizontally expanding the earlier composition on a larger scale. Yet here Frelinghuysen explores a greater spatial complexity; instead of objects resting on the table constituting the top layer of forms, the objects are instead often signified by negative spaces: for example, corrugated cardboard is cut to suggest the surface of the table or the central glass. The weaving of layered collage elements and wordplay connect Frelinghuysen's collages to many of Picasso's early Synthetic Cubist collages, such as Guitar and Bottle, 1913 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), in Gallatin's collection. Her apparently arbitrary slices of words actually address an informed viewer. Frelinghuysen refers directly to her aesthetic affiliations at the left, in the newspaper fragment reading "France." Yet she slips in a more oblique reference in the fragments of "J.-J. P." and "ud" (where the shape of the bottle is perhaps intended as a witty gesture to represent "O") which refer to the Dutch De Stijl architect Jacobus Johannes Pieter Oud, who integrated a distinctive form of typography into his innovative modernist architecture. This painting received favorable critical notices at its exhibition in the Whitney Annual in 1944. It was reproduced in Art Digest, which praised it as one of the best works in the exhibition.3

While Morris and Gallatin did not always claim originality in aesthetic matters, they could take credit for fostering the career ol a successful woman abstract artist.4 Frelinghuysen kept most of her thoughts on aesthetic matters private and made few public pronouncements. Morris and Gallatin did promote her, however, in order to further their own intellectual and aesthetic ideals. Both art and popular publications such as Life habitually stressed the exceptional nature of women's achievements in art during the 1930s and 1940s. Frelinghuysen was included in the 1943 Thirty-One Women exhibition at the Art of This Century gallery, which attempted to break new ground by exposing women's abilities in surrealist and abstract art, and which was selected by a jury that included among others Duchamp, Ernst, and André Breton. The press release cited the exhibition as proof that "the creative ability of women is by no means restricted to the decorative vein as could be deducted [sic] from the history of art by women throughout the ages."5 This was doubly meaningful for supporters of abstract art, since at the time abstract art was often castigated as merely "decorative." Gallatin may have had a similar publicity strategy in mind when he planned a solo exhibition of Frelinghuysen's work, which was halted upon the closing of the Museum of Living Art. In 1938 he announced that he had acquired the first work by a woman artist for the museum's permanent collection, Frelinghuysen's 1937 papier collé entitled Carmen (fig. 16). Indeed, both Gallatin and Morris often highlighted aspects of Frelinghuysen's work that were closest to their own paintings, collections, or critical investments. In the biographical notes for Gallatin's catalogue of the Museum of Living Art, Morris wrote that her work managed to "project a personality through the sense of touch that contrasts with the studied anonymity of the numerous Constructivist followers."6

Frelinghuysen's various signatures reflect her self-fashioning as an artist. Her choice of signature always corresponds to compositional dictates, either integrated as a visual accent (as in Printemps [pl. viii]), or absent so as not to detract from more fully abstract compositions (as in Composition [pl. xiii]). Although she performed onstage under her married name, in painting she underlined her independence from her husband by signing her maiden name. Occasionally Frelinghuvsen wrote out her full surname, but more often she used initials. Her signature on Printemps, where initials appear to have been applied with a stencil, provides a telling metaphor tor her artistic contributions: Frelinghuysen worked within the pre-established forms of Cubist visual vocabulary but deployed these elements in a unique way that asserted her own artistic identity.

1. Mildred Faulk, "Singer Suzy Is Painter Susie," New York Sun, May 11, 1948, 27.

2. Quoted in John R. Lane and Susan C. Larsen, eds., Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, 1927—1944, exh. cat. (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute, Museum of Art; New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1983), 80.

3. See Margaret Breuning, "Whitney Annual—A Provocative But Inconclusive Exhibition," Art Digest 19, no. 5 (December 1, 1944), 5—6.

4. Other women in the AAA at this time who were also successful abstract artists included Gertrude Greene, Esphyr Slobodkina, and Alice Trumbull Mason.

5. Quoted in Melvin Paul Lader, "Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century: The Surrealist Milieu and the American Avant-Garde, 1942—1947," Ph.D. diss., University of Delaware, 1981, 197.

6. George L. K. Morris, in A. E. Gallatin, Museum of Living Art, A. E. Gallatin Collection (New York: New York University, 1940), n.p., cat. 146.