Rovinj • Pula • The Brijuni Islands • Poreč • Hill Towns • Opatija and Rijeka

Hill Towns of the Istrian Interior

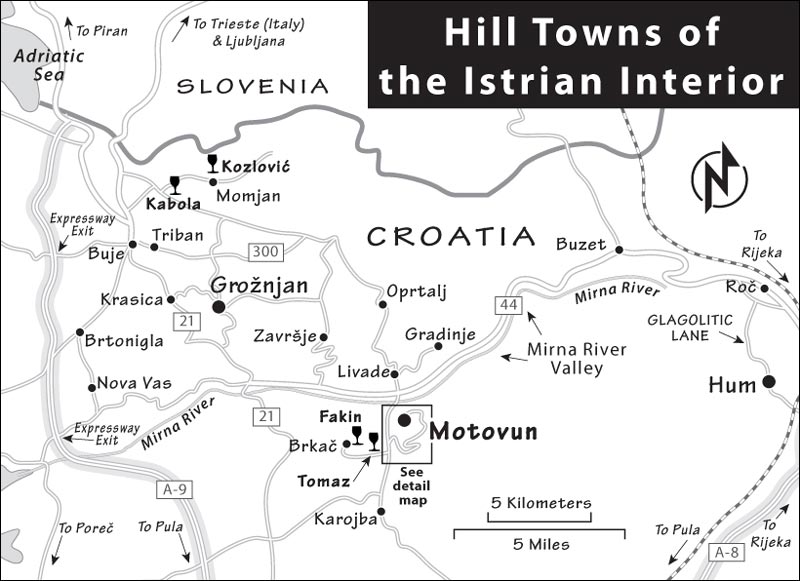

Idyllic Istria (EE-stree-ah; “Istra” in Croatian), at Croatia’s northwest corner, reveals itself to you gradually and seductively. Pungent truffles, Roman ruins, striking hill towns, quaint coastal villages, carefully cultivated food and wine, and breezy Italian culture all compete for your attention. The wedge-shaped Istrian Peninsula, while not as famous as its southern rival (the much-hyped Dalmatian Coast), is giving Dalmatia a run for its money.

The Istrian coast, with gentle green slopes instead of the sheer limestone cliffs found along the rest of the Croatian shoreline, is more serene than sensational. It’s lined with pretty, interchangeably tacky resort towns, such as the tourist mecca Poreč (worthwhile only for its mosaic-packed Byzantine basilica). But one seafront village reaches the ranks of greatness: romantically creaky Rovinj, my favorite little town on the Adriatic. Down at the tip of Istria is big, industrial Pula, offering a bustling urban contrast to the rest of the time-passed coastline, plus some impressive Roman ruins (including an amphitheater so remarkably intact, you’ll marvel that you haven’t heard of it before). Just offshore are the Brijuni Islands—once the stomping grounds of Marshal Tito, whose ghost still haunts a national park peppered with unexpected attractions.

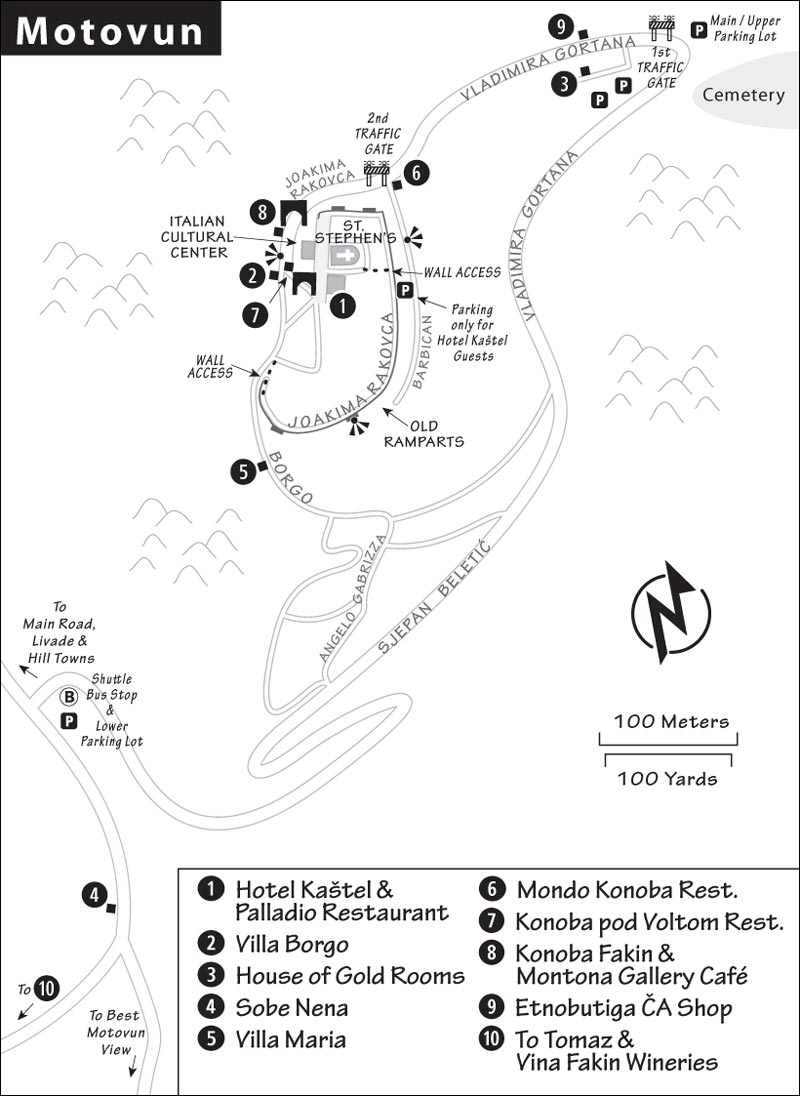

But Croatia is more than the sea, and diverse Istria offers some of the country’s most appealing reasons to head inland. In the Istrian interior, between humble concrete towns crying out for a paint job, you’ll find vintners painstakingly reviving a delicate winemaking tradition, farmers pressing that last drop of oil out of their olives, trained dogs sniffing out truffles in primeval forests, and a smattering of fortified medieval hill towns with sweeping views over the surrounding terrain—including the justifiably popular village of Motovun.

Istria offers an exciting variety of attractions compared to the relatively uniform, if beautiful, string of island towns farther south. While some travelers wouldn’t trade a sunny island day for anything, I prefer to sacrifice a little time on the Dalmatian Coast for the diversity that comes with a day or two exploring Istria’s hill towns and other unique sights.

Istria’s main logistical advantage is that it’s easy to reach and to explore by car. Just a quick hop from Venice or Slovenia, compact little Istria is made-to-order for a quick, efficient road trip.

With a car and two weeks to spend in Croatia and Slovenia, Istria deserves two days, divided between its two big attractions: the coastal town of Rovinj and the hill towns of the interior. Ideally, make your home base for two nights in Rovinj or in Motovun, and day-trip to the region’s other attractions. To wring the most out of limited Istrian time, the city of Pula and its Roman amphitheater are well worth a few hours. If you have a car, it’s easy to go for a joyride through the Istrian countryside, visiting a few hill towns and wineries en route. The town of Poreč and the fun but time-consuming Brijuni Islands merit a detour only if you’ve got at least three days.

Istria is a cinch for drivers, who find distances short and roads and attractions well-marked (though summer traffic can be miserable, especially on weekends). Istria is neatly connected by a speedy highway nicknamed the ipsilon (the Croatian word for the letter Y, which is what the highway is shaped like). One branch of the “Y” (A-9) runs roughly parallel to the coast from Slovenia to Pula, about six miles inland; the other branch (A-8) cuts diagonally northeast to the Učka Tunnel (leading to Rijeka). You’ll periodically come to toll booths, where you’ll pay a modest fee for using the ipsilon. Following road signs here is easy (navigate by town names), but if you’ll be driving a lot, pick up a good map to more easily navigate the back roads. As you drive, keep an eye out for characteristic stone igloos called kažun (a symbol of Istria). Formerly used as very humble residences, now the few surviving structures—sometimes built right into a dry-stone wall—are mostly used as shelter for farmers caught in the rain.

If you’re relying on public transportation, Istria can be frustrating: The towns that are easiest to reach (Poreč and Pula) are less appealing than Istria’s highlights (Rovinj and Motovun). Linking up the coastal towns by bus is doable if you’re patient and check schedules carefully, but the hill towns probably aren’t worth the hassle. Even if you’re doing the rest of your trip by public transportation, consider renting a car for a day or two in Istria.

Driving from Istria to Rijeka (and the Rest of Croatia): Istria meets the rest of Croatia at the big port city of Rijeka (described at the end of this chapter). There are two ways to get to Rijeka: The faster alternative is to take the ipsilon road via Pazin to the Učka Tunnel (28-kn toll), which emerges just above Rijeka and Opatija (for Rijeka, you’ll follow the road more or less straight on; for Opatija, you’ll twist down to the right, backtracking slightly to the seashore below you). Or you can take the slower but more scenic coastal road from Pula via Labin. After going inland for about 25 miles, this road jogs to the east coast of Istria, which it hugs all the way into Opatija, then Rijeka.

From Rijeka, you can easily hook into Croatia’s expressway network (for example, take A-6 east to A-1, which zips you north to Zagreb or south to the Dalmatian Coast). For more driving tips, see the end of this chapter.

By Boat to Venice, Piran, or Trieste: Various companies connect Venice daily in summer with Rovinj, Poreč, and Pula (about three hours). While designed for day-trippers from Istria to Venice, these services can be used for one-way travel. As the companies and specific routes change from year to year, check each of these websites to see what might work for your itinerary: Venezia Lines (www.venezialines.com), Adriatic Lines (www.adriatic-lines.com), and Commodore Cruises (www.commodore-cruises.hr). Trieste Lines (www.triestelines.it) connects Rovinj and Poreč to Piran (Slovenia), then Trieste (Italy).

Rising dramatically from the Adriatic as though being pulled up to heaven by its grand bell tower, Rovinj (roh-VEEN; in Italian: Rovigno/roh-VEEN-yoh) is a welcoming Old World oasis in a sea of tourist kitsch. Among the villages of Croatia’s coast, there’s something particularly romantic about Rovinj—the most Italian town in Croatia’s most Italian region. Rovinj’s streets are delightfully twisty, its ancient houses are characteristically crumbling, and its harbor—lively with real-life fishermen—is as salty as they come. Like a little Venice on a hill, Rovinj is the atmospheric setting of your Croatian seaside dreams.

Rovinj was prosperous and well-fortified in the Middle Ages. It boomed in the 16th and 17th centuries, when it was flooded with refugees fleeing both the Ottoman invasions and the plague. Because the town was part of the Republic of Venice for five centuries (13th to 18th centuries), its architecture, culture, and even language are strongly Venetian. The local folk groups sing in a dialect actually considered more Venetian than what the Venetians themselves speak these days. (You can even see Venice from Rovinj’s church bell tower on a very clear day.)

After Napoleon seized the region, then was defeated, Rovinj became part of Austria. The Venetians had neglected Istria, but the Austrians invested in it, bringing the railroad, gas lights, and a huge Ronhill tobacco factory. (This factory—recently replaced by an enormous, state-of-the-art facility you’ll pass on the highway farther inland—is one of the town’s most elegant structures, and is slated for extensive renovation in the coming years.) The Habsburgs tapped Pula and Trieste to be the empire’s major ports—cursing those cities with pollution and sprawl, while allowing Rovinj to linger in its trapped-in-the-past quaintness.

Before long, Austrians discovered Istria as a handy escape for a beach holiday. Tourism came to Rovinj in the late 1890s, when a powerful Austrian baron bought one of the remote, barren islands offshore and brought it back to life with gardens and a grand villa. Before long, another baron bought another island...and a tourist boom was under way. In more recent times, Rovinj has become a top destination for nudists. The resort of Valalta, just to the north, is a popular spot for those seeking “southern exposure”...as a very revealing brochure at the TI illustrates (www.valalta.hr). Whether you want to find PNBs (pudgy nude bodies), or avoid them, remember that the German phrase FKK (Freikörper Kultur, or “free body culture”) is international shorthand for nudism.

Rovinj is the most atmospheric of all of Croatia’s small coastal towns. Maybe that’s because it’s always been a real town, where poor people lived. You’ll find no fancy old palaces here—just narrow streets lined with skinny houses that have given shelter to humble families for generations. While it’s becoming known on the tourist circuit, Rovinj retains the soul of a fishermen’s village; notice that the harbor is still filled not with glitzy yachts, but with a busy fishing fleet.

Rovinj is hardly packed with diversions. You can get the gist of the town in a one-hour wander. The rest of your time is for enjoying the ambience, savoring a slow meal, or pedaling a rental bike to a nearby beach. When you’re ready to overcome your inertia, there’s no shortage of day trips (the best are outlined in this chapter). Be aware that much of Rovinj (like other small Croatian coastal towns) closes down from mid-October through Easter.

Rovinj, once an island, is now a peninsula. The Old Town is divided in two parts: a particularly charismatic chunk on the oval-shaped peninsula, and the rest on the mainland (with similarly time-worn buildings, but without the commercial cuteness that comes with lots of tourist money). Where the mainland meets the peninsula is a broad, bustling public space called Tito Square (Trg Maršala Tita). The Old Town peninsula—traffic-free except for the occasional moped—is topped by the massive bell tower of the Church of St. Euphemia. At the very tip of the peninsula is a small park.

Rovinj’s TI, facing the harbor, has several handy, free materials, including a town map and an info booklet (June-Sept daily 7:00-22:00; Oct and May daily 8:00-21:00; Nov-April Mon-Fri 8:00-15:00, Sat 8:00-13:00, closed Sun; along the embankment at Obala Pina Budičina 12, tel. 052/811-566, www.tzgrovinj.hr).

By Car: Only local cars are allowed to enter the Old Town area (though if you’re overnighting in this area, they may let you drive in just long enough to drop off your bags—ask your host for details). To get as close as possible—whether you’re staying in the Old Town, or just visiting for the day—use the big waterfront Valdibora parking lots just north of the Old Town, which come with the classic Rovinj view (July-Aug: 6.5 kn/hour, April-June and Sept: 5 kn/hour, Oct-March: 2 kn/hour). As you drive in from the highway through the outskirts of Rovinj, the road forks, sending most hotel traffic to the left (turn off here if you’re staying outside the Old Town); but if you want to reach the Old Town, go right instead, then follow Centar signs, which eventually lead you directly to the two Valdibora lots: “Valdibora 1” (a.k.a. “Big Valdibora,” farther from the Old Town), then “Valdibora 2” (a.k.a. “Little Valdibora,” closer to the Old Town). During busy times, the slightly closer Valdibora 2 is reserved for residents; in this case, signs will divert you into Valdibora 1.

If both Valdibora lots are full, you’ll be pushed to another pay lot farther out, along the bay northwest of the Old Town (a scenic 15-minute walk from town; summer: 5-6 kn/hour, free 23:00-6:00; winter: 2 kn/hour, free 20:00-6:00 and on Sun). Even if the Valdibora lots are available, budget-oriented drivers may prefer this somewhat cheaper outer lot—the cost adds up fast if you’re parking over several nights. Accommodations outside of the Old Town generally have on-site (or nearby streetside) parking, often free; a few places in the Old Town have parking available outside of town.

By Bus: The bus station is on the south side of the Old Town, close to the harbor. Leave the station to the left, then walk on busy Carera street directly into the center of town. Note that there are plans to move the bus station to the other side of the Old Town, just above the long waterfront parking lots. If your bus stops here instead, simply head down to the main road and walk along the parking lots into town.

By Boat: The few boats connecting Rovinj to Venice, Piran, Trieste, and other Istrian towns dock at the long pier protruding from the Old Town peninsula. Just walk up the pier, and you’re in the heart of town.

Internet Access: In public areas (such as the harborfront square), check for a free (if slow) Wi-Fi signal called “Hotspot Croatia.” A-Mar Internet Club has pay Wi-Fi, several terminals, and long hours (36 kn/hour at a terminal, 10 kn/hour for Wi-Fi, daily 9:00-22:00, shorter hours off-season, on the main drag in the mainland part of the Old Town, Carera 26, tel. 052/841-211).

Laundry: The full-service Galax launderette hides up the street beyond the bus station. You can usually pick up your laundry after 24 hours, though same-day service might be possible if you drop it off early enough in the morning (90 kn/load wash and dry; Easter-Sept daily 6:00-20:00, until later in summer; Oct-Easter Mon-Fri 7:00-19:00, Sat 9:00-15:00, closed Sun; up Benussia street past the bus station, on the left after the post office, tel. 052/816-130).

Local Guide: Vukica Palčić is a very capable guide who knows her town intimately and loves to share it with visitors (€50 for a 1.5-hour tour, mobile 098-794-003, vukica.palcic@pu.t-com.hr).

Best Views: The town is full of breathtaking views. Photography buffs will be busy in the magic hours of early morning and evening, and even by moonlight. The postcard view of Rovinj is from the parking lot embankment at the north end of the Old Town (at the start of the “Self-Guided Walk,” next). For a different perspective on the Old Town, head for the far side of the harbor on the opposite (south) end of town. The church bell tower provides an almost aerial view of the town and a grand vista of the outlying islands.

This orientation walk introduces you to Rovinj in about an hour. Begin at the parking lot just north of the Old Town.

Many places offer fine views of Rovinj’s Old Town, but this is the most striking. Boats bob in the harbor, and behind them Venetian-looking homes seem to rise from the deep. (For an aerial perspective, notice the big billboard overhead and to the left.)

The Old Town is topped by the church, whose bell tower is capped by a weathervane in the shape of Rovinj’s patron saint, Euphemia. Local fishermen look to this saintly weathervane for direction: When Euphemia is looking out to sea, it means the stiff, fresh Bora wind is blowing, bringing dry air from the interior...a sailor’s delight. But if she’s facing the land, the humid Jugo wind will soon bring bad weather from the sea. After a day or so, even a tourist learns to look to St. Euphemia for the weather forecast. (For more on Croatian winds and weather, see the sidebar on here.)

As you soak in this scene, ponder how the town’s history created its current shape. In the Middle Ages, Rovinj was an island, rather than a peninsula, and it was surrounded by a double wall—a protective inner wall and an outer seawall. Because it was so well-defended against pirates and other marauders (and carefully quarantined from the plague), it was extremely desirable real estate. And yet, it was easy to reach from the mainland, allowing it to thrive as a trading town. With more than 10,000 residents at its peak, Rovinj became immensely crowded, which explains today’s pleasantly claustrophobic Old Town.

Over the centuries—as demand for living space trumped security concerns—the town walls were converted into houses, with windows grafted on to their imposing frame. Gaps in the wall, with steps that seem to end at the water, are where fishermen would pull in to unload their catch directly into the warehouses on the bottom level of the houses. (Later you can explore some of these lanes from inside the town.) Today, if you live in one of these houses, the Adriatic is your backyard.

• Now head into town. In the little park near the sea, just beyond the end of the parking lot, look for the big, blocky...

Dating from the time of Tito, this celebrates the Partisan Army’s victory over the Nazis in World War II and commemorates the victims of fascism. The minimalist reliefs on the ceremonial tomb show a slow prisoners’ parade, the victims prodded by a gun in the back from a figure with a Nazi-style helmet. Notice that one side of the monument is in Croatian, and the other is in Italian. With typical Yugoslav grace and subtlety, this jarring block shatters the otherwise harmonious time-warp vibe of Rovinj. Fortunately, it’s the only modern structure anywhere near the Old Town.

• Now walk a few more steps toward town and past the playground, stopping to explore the covered...

The front part of the market, near the water, is for souvenirs. But natives delve deeper in, to the produce stands. Separating the gifty stuff from the nitty-gritty produce is a line of merchants aggressively pushing free samples. Everything is local and mostly homemade. Consider this snack-time tactic: Loiter around, joking with the farmers while sampling their various tasty walnuts, figs, cherries, grapes, olive oils, honey, rakija (the powerful schnapps popular throughout the Balkans), and more. If the sample is good, buy some more for a picnic. In the center of the market, a delightful and practical fountain from 1908 reminds locals of the infrastructure brought in by their Habsburg rulers a century ago. The hall labeled Ribarnica/Pescheria at the back of the market is where you’ll find fresh, practically wriggling fish. This is where locals gather ingredients for their favorite dish, brodet—a stew of various kinds of seafood mixed with olive oil and wine...all of Istria’s best bits rolled into one dish. It’s slowly simmered and generally served with polenta (unfortunately, it’s rare in restaurants).

• Continue up the broad street, named for Giuseppe Garibaldi—one of the major players in late 19th-century Italian unification. Imagine: Even though you’re in Croatia, Italian patriots are celebrated in this very Italian-feeling town (see the “Italo-Croatia” sidebar). After one long block, on your left, you’ll come to the wide cross-street called...

This marks the site of the medieval bridge that once connected the fortified island of Rovinj to the mainland (as illustrated in the small painting above the door of the Kavana al Ponto—“Bridge Café”). Back then, the island was populated mostly by Italians, while the mainland was the territory of Slavic farmers. But as Rovinj’s strategic importance waned, and its trading status rose, the need for easy access became more important than the canal’s protective purpose—so in 1763, it was filled in. The two populations integrated, creating the bicultural mix that survives today.

Notice the breeze? Via Garibaldi is nicknamed Val di Bora (“Valley of the Bora Wind”) for the constant cooling wind that blows here. On the island side of Trg na Mostu is the Rovinj Heritage Museum (described later, under “Sights in Rovinj”). Next door, the town’s cultural center posts lovingly hand-lettered signs in Croatian and Italian announcing upcoming musical events (generally free, designed for locals, and worth noting and enjoying).

Nearby (just past Kavana al Ponto, on the left), the Viecia Batana Café—named for Rovinj’s unique, flat-bottomed little fishing boats—has a retro interior with a circa-1960 fishermen’s mural that evokes an earlier age. The café is popular for its chocolate cake and “Batana” ice cream.

• Now proceed (passing handwritten signs in Croatian and Italian listing upcoming events) to the little fountain in the middle of the square, facing the harbor.

This wide-open square at the entrance to the Old Town is the crossroads of Rovinj. The fountain, with a little boy holding a water-spouting fish, celebrates the government-funded water system that finally brought running water to the Old Town in 1959. Walk around the fountain, with your eyes on the relief, to see a successful socialist society at the inauguration of this new water system. Despite the happy occasion, the figures are pretty stiff—conformity trumped most other virtues in Tito’s world.

Now walk out to the end of the concrete pier, called the Mali Molo (“Little Pier”). From here, you’re surrounded by Rovinj’s crowded harbor, with fishing vessels and excursion boats that shuttle tourists out to the offshore islands. If the weather’s good, a boat trip can be a fun way to get out on the water for a different angle on Rovinj (see “Activities in Rovinj,” later, for details).

Scan the harbor. On the left is the MMC, the local meeting and concert hall (described later, under “Nightlife in Rovinj”). Above and behind the MMC, the highest bell tower inland marks the Franciscan monastery, which was the only building on the mainland before the island town was connected to shore. Along the waterfront to the right of the MMC is the multicolored Hotel Park, a typical monstrosity from the communist era, now tastefully renovated inside. A recommended bike path starts just past this hotel, leading into a nature preserve and the best nearby beaches (which you can see in the distance; for more on bike rental, see “Activities in Rovinj,” later).

Now head back to the base of the pier. If you were to walk down the embankment between the harbor and the Old Town (past Hotel Adriatic), you’d find the TI, the recommended House of the Batana Boat museum, and a delightful “restaurant row” with several tempting places for a drink or a meal. Many fishermen pull their boats into this harbor, then simply carry their catch across the street to a waiting restaurateur. (This self-guided walk finishes with a stroll down this lane.)

Backtrack 20 paces past the fountain and face the Old Town entrance gate, called the Balbi Arch. The winged lion on top is a reminder that this was Venetian territory for centuries.

• Head through the gate into the Old Town. Inside and on the left is the red...

On the old Town Hall, notice another Venetian lion, as well as other historic crests embedded in the wall. The Town Hall actually sports an Italian flag (along with ones for Rovinj, Croatia, and the EU) and faces a square named for Giacomo Matteotti, a much-revered Italian patriot.

Continue a few more steps into town. Gostionica/Trattoria Cisterna faces another little square, which once functioned as a cistern (collecting rainwater, which was pulled from a subterranean reservoir through the well you see today). The building on your left is the Italian Union—yet another reminder of how Istria has an important bond with Italy.

• Now begin walking up the street to the left of Gostionica/Trattoria Cisterna. Passing the recommended Piassa Granda wine bar on your left, veer right up...

The main “street” (actually a tight lane) leading through the middle of the island is choked with tourists during the midday rush and lined with art galleries. This inspiring town has attracted many artists, some of whom display their works along this colorful stretch. Notice the rusty little nails speckling the walls—each year in August, an art festival invites locals to hang their best art on this street. With paintings lining the lane, the entire community comes out to enjoy each other’s creations.

As you walk, keep your camera ready, as you can find delightful scenes down every side lane. Remember that, as crowded as it is today, little Rovinj was even more packed in the Middle Ages. Keep an eye out for arches that span narrow lanes (such as on the right, at Arsenale street)—the only way a walled city could grow was up. Many of these additions created hidden little courtyards, nooks, and crannies that make it easy to get away from the crowds and claim a corner of the town for yourself. Another sign of Rovinj’s overcrowding are the distinctive chimneys poking up above the rooftops. These chimneys, added long after the buildings were first constructed, made it possible to heat previously underutilized rooms...and squeeze in even more people.

• Continue up to the top of Grisia. Capping the town is the can’t-miss-it...

Rovinj’s landmark Baroque church dates from 1754. It’s watched over by an enormous 190-foot-tall campanile, a replica of the famous bell tower on St. Mark’s Square in Venice. The tower is topped by a copper weathervane with the weather-predicting St. Euphemia, the church’s namesake.

Cost and Hours: Free, generally open May-Sept daily 10:00-18:00, Easter-April and Oct-Nov open only for Mass and with demand, generally closed Dec-Easter.

Visiting the Church: The vast, somewhat gloomy interior boasts some fine altars of Carrara marble (a favorite medium of Michelangelo’s). Services here are celebrated using a combination of Croatian and Italian, suiting the town’s mixed population.

To the right of the main altar is the church’s highlight: the chapel containing the relics of St. Euphemia. Before stepping into the chapel, notice the altar featuring Euphemia—depicted, as she usually is, with her wheel (a reminder of her torture) and a palm frond (symbolic of her martyrdom), and holding the fortified town of Rovinj, of which she is the protector.

Now head into the little chapel behind the altar. In the center is a gigantic tomb, and on the walls above are large paintings that illustrate two significant events from the life of this important local figure. St. Euphemia was the virtuous daughter of a prosperous early fourth-century family in Chalcedon (near today’s Istanbul). Euphemia used her family’s considerable wealth to help the poor. Unfortunately, her pious philanthropy happened to coincide with anti-Christian purges by the Roman Emperor Diocletian. When she was 15 years old, Euphemia was arrested for refusing to worship the local pagan idol. She was brutally tortured, her bones broken on a wheel. Finally she was thrown to the lions as a public spectacle. But, the story goes, the lions miraculously refused to attack her. You can see this moment depicted in one of the paintings above—as a bored-looking lion tenderly nibbles at her right bicep.

Flash forward to the year 800, when a gigantic marble sarcophagus containing St. Euphemia’s relics somehow found its way into the Adriatic and floated all the way up to Istria, where Rovinj fishermen discovered it bobbing in the sea. They tugged it back to town, where a crowd gathered. The townspeople realized what it was and wanted to take it up to the hilltop church. But nobody could move it...until a young boy with two young calves showed up. He said he’d had a dream of St. Euphemia—and, sure enough, he succeeded in dragging her relics to where they still lie. In the painting above, see the burly fishermen looking astonished as the boy succeeds in moving the giant sarcophagus. Note the depiction of Rovinj fortified by a double crenellated wall—looking more like a castle than like the creaky fishing village of today. At the top of the hill is an earlier version of today’s church.

Now turn your attention to Euphemia’s famous sarcophagus. The front panel (with the painting of Euphemia) is opened with much fanfare every September 16, St. Euphemia’s feast day, to display the small, withered, waxen face of Rovinj’s favorite saint.

• If you have time and energy, consider climbing the...

Scaling the church bell tower’s creaky wooden stairway requires an enduring faith in the reliability of wood. It rewards those who brave its 192 stairs with a commanding view of the town and surrounding islands. The climb doubles your altitude, and from this perch you can also look down—taking advantage of the quirky little round hole in the floor to photograph the memorable staircase you just climbed.

Cost and Hours: 15 kn, same hours as church, enter from inside church—to the left of the main altar.

• Leave the church through the main door. A peaceful café on a park terrace (once a cemetery) is just ahead and below you. Just to the right, a winding, cobbled lane leads past the café entrance and down toward the water, then forks. A left turn here zigzags you past a WWII pillbox and leads along the “restaurant row,” where you can survey your options for a drink or a meal (see “Eating in Rovinj,” later). A right turn curls you down along the quieter northern side of the Old Town peninsula. Either way, Rovinj is yours to enjoy.

Rovinj has a long, noble shipbuilding tradition, and this tiny but interesting museum gives you the story of the town’s distinctive batana boats. Locals say this museum puts you in touch with the soul of Rovinj.

The flat-bottomed vessels are favored by local fishermen for their ability to reach rocky areas close to shore that are rich with certain shellfish. The museum explains how the boats are built, with the help of an entertaining time-lapse video showing a boat built from scratch in five minutes. You’ll also meet some of the salty old sailors who use these vessels (find the placemat with wine stains, and put the glass in different red circles to hear various seamen talk in the Rovinj dialect). Another movie shows the boats at work. Upstairs is a wall of photos of batana boats still in active use, a tiny library (peruse photos of the town from a century ago), and a video screen displaying bitinada music—local music with harmonizing voices that imitate instruments. Sit down and listen to several (there’s a button for skipping ahead). The museum has no posted English information, so pick up the comprehensive English flier as you enter.

Cost and Hours: 10 kn; June-Sept daily 10:00-14:00 & 19:00-23:00; Oct-Dec and March-May Tue-Sun 10:00-13:00 & generally also 16:00-18:00, closed Mon; closed Jan-Feb; Obala Pina Budicina 2, tel. 052/812-593, mobile 091-154-6598, www.batana.org, Ornela.

Activities: The museum, which serves as a sort of cultural heritage center for the town, also presents a variety of engaging batana-related activities. On some summer evenings, you can take a boat trip on a batana from the pier near the museum. The trip, which is accompanied by traditional music, circles around the end of the Old Town peninsula and docks on the far side, where a traditional wine cellar has a fresh fish dinner ready, with local wine and more live music (June-mid-Sept, generally Tue and Thu at 20:30, boat trip-60 kn, dinner-160 kn extra, visit or call the museum the day before to reserve). Also on some summer evenings, you can enjoy an outdoor food market with traditional Rovinj foods and live bitinada music. The centerpiece is a batana boat being refurbished before your eyes (in front of museum, 20-30-kn light food, mid-June-early Sept generally Tue and Sat 20:00-23:00). Even if you’re here off-season, ask at the museum if anything special is planned.

This ho-hum museum combines art old (obscure classic painters) and new (obscure contemporary painters from Rovinj) in an old mansion. Rounding out the collection are some model ships, a small archaeological exhibit, and temporary exhibits.

Cost and Hours: 15 kn; mid-June-mid-Sept Tue-Fri 10:00-14:00 & 18:00-22:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-14:00 & 19:00-22:00, closed Mon; off-season Tue-Sat 10:00-13:00, closed Sun-Mon; Trg Maršala Tita 11, tel. 052/816-720, www.muzej-rovinj.com.

This century-old collection of local sea life is one of Europe’s oldest aquariums. Unfortunately, it’s also tiny (with three sparse rooms holding a few tanks of what you’d see if you snorkeled here), disappointing, and overpriced.

Cost and Hours: 30 kn, daily June-Aug 9:00-21:00, Sept 9:00-20:00, Oct-May 10:00-16:00 or longer depending on demand, across the street from the end of the waterfront parking lot at Obala G. Paliage 5, tel. 052/804-712.

For a different view of Rovinj, consider a boat trip. The scenery is pleasant rather than thrilling, but the craggy and tree-lined coastline and offshore islets are a lovely backdrop for an hour or two at sea. You’ll see captains hawking boat excursions at little shacks all along Rovinj’s harbor. The most common option is a 1.5-hour loop around the “Golden Cape” (Zlatni Rt) and through Rovinj’s own little archipelago for about 75 kn; this is most popular at sunset. For a longer cruise, consider the four-hour, 150-kn sail north along the coast and into the underwhelming Limski Canal (a.k.a. “Limski Fjord”), where you’ll have one to two hours of free time. Dolphin sightings are not unusual, and some outfits throw in a “fish picnic” en route for extra. Stroll the harbor and comparison-shop to find the option that suits your interest.

You can also take a boat to one of the larger offshore islands. This lets you get away from the crowds and explore some relatively untrampled beaches. These boats—run by the big hotel chain with branches on those islands—depart about hourly from the end of the concrete pier in the Old Town known as the Mali Molo (“Little Pier”). The two choices are St. Catherine (Sv. Katarina—the lush, green island just across the harbor, about a 5-minute trip, 25 kn) and Red Island (Crveni Otok—farther out, about a 15-minute trip, boats may be marked “Hotel Istra,” 40 kn).

Rovinj doesn’t have any sandy beaches—just rocky ones. (The nearest thing to a sandy beach is the small, finely pebbled beach on Red Island/Crveni Otok.) The most central spot to swim or sunbathe is at Balota Beach, on the rocks along the embankment on the south side of the Old Town peninsula, just past La Puntuleina restaurant (no showers, but scenic and central). On nice days, Balota can get crowded; if you continue around Rovinj’s peninsula to the tip, just before the old WWII pillbox you’ll find the more secluded “Pillbox Beach,” where steps lead steeply down to a cluster of more secluded rocks. For bigger beaches, go to the wooded Golden Cape (Zlatni Rt) south of the harbor (past the big, waterfront Hotel Park). This cape is lined with walking paths and beaches, and shaded by a wide variety of trees and plants. For a scenic sunbathing spot, choose a perch facing Rovinj on the north side of the Golden Cape. Another beach, called Kuvi, is beyond the Golden Cape. To get away from it all, take a boat to an island on Rovinj’s little archipelago (see previous listing).

The TI’s free, handy biking map suggests a variety of short and long bike rides. The easiest and most scenic is a quick loop around the Golden Cape (Zlatni Rt, described above). You can do this circuit and return to the Old Town in about an hour (without stops). Start by biking south around the harbor and past the waterfront Hotel Park, where you leave the cars and enter the wooded Golden Cape. Peaceful miniature beaches abound. The lane climbs to a quarry (much of Venice was paved with Istrian stone), where you’re likely to see beginning rock climbers inching their way up and down. Cycling downhill from the quarry and circling the peninsula, you hit the Lovor Grill (open daily in summer 10:00-16:00 for drinks and light meals)—a cute little restaurant housed in the former stables of the Austrian countess who planted what today is called “Wood Park.” From there, you can continue farther along the coast or return to town (backtrack two minutes and take the right fork through the woods back to the waterfront path).

For a more ambitious, inland pedal, pick up the TI’s free Basìlica bike map, which narrates a 12-mile loop that connects several old churches.

Bike Rental: Bikes are rented at subsidized prices from the city parking lot kiosk (5 kn/hour, open 24 hours daily except no rentals in winter, fast and easy process; choose a bike with enough air in its tires or have them pumped up, as the path is rocky and gravelly). Various travel agencies around town rent bikes for much more (around 20 kn/hour); look for signs—especially near the bus station—or ask around.

Rovinj is a delight after dark. Views that are great by day become magical in the moonlight and floodlight. The streets of the Old Town are particularly inviting when empty and starlit.

Lots of low-key, small-time music events take place right in town (ask at the TI, check the events calendar at www.tzgrovinj.hr, and look for handwritten signs in Croatian and Italian on Garibaldi Street near the Square at the Bridge). Groups perform at various venues around town: right along the harborfront (you’ll see the bandstand set up); in the town’s churches (especially St. Euphemia and the Franciscan church); in the old cinema/theater by the market; at the pier in front of the House of the Batana Boat (described earlier, under “Sights in Rovinj”); and at the Multi-Media Center (a.k.a. the “MMC,” which locals call “Cinema Belgrade”—its former name), in a cute little hall above a bank across the harbor from the Old Town.

Rovinj has two good places to sample Istrian and Croatian wines, along with light, basic food—such as prosciutto-like pršut, truffles, and olive oil. Remember, two popular local wines worth trying are malvazija (a light white) and teran (a heavy red). At Bacchus Wine Bar, owner Paolo serves about 80 percent Istrian wines, with the rest from elsewhere in Croatia and international vintners (15-60 kn/deciliter, most around 20-30 kn, 65-250-kn bottles, daily 7:00-1:00 in the morning, shorter hours off-season, Carera 5, tel. 052/812-154). Piassa Granda, on a charming little square right in the heart of the Old Town, has a classy, cozy interior and more than 100 types of wine (25-35-kn glasses, 40-70-kn Istrian small plates, more food than Bacchus, daily 10:00-16:00 & 18:00-24:00, Veli trg 1, mobile 098-824-322, Helena).

Valentino Champagne and Cocktail Bar is a romantic, justifiably pretentious place for an expensive late-night waterfront drink. Fish, attracted by its underwater lights, swim by from all over the bay...to the enjoyment of those nursing a cocktail on the rocks (literally—you’ll be given a small seat cushion to plunk down in your own seaside niche). Or you can choose to sit on one of the terraces. Classy candelabras twinkle in the twilight, as couples cozy up to each other and the view. While the drinks are extremely pricey, this place is unforgettably cool (60-75-kn cocktails, 60-kn non-alcoholic drinks, daily April-May 12:00-24:00, June-Sept 18:00-24:00, closed Oct-March, Via Santa Croce 28, tel. 052/830-683, Patricia).

If Valentino is too pricey, too chichi, or too crowded for your tastes, a couple of alternatives are nearby. The Monte Carlo bar, along the same drag but a bit closer to the harbor, is fun-loving and serves much cheaper drinks (25-30 kn), but lacks the atmospheric “on the rocks” setting of Valentino (daily 8:00-late, closed Oct-Easter, mobile 091-579-1813). Or consider La Puntuleina, beyond Valentino, with a similarly rocky ambience but lower prices (20-40-kn drinks) and a bit less panache (listed later, under “Eating in Rovinj”). I’d scout all three and pick the ambience you prefer.

In summer, the House of the Batana Boat often hosts special events such as a boat trip and traditional dinner, and an outdoor food court. For details, see the listing earlier, under “Sights in Rovinj.”

As throughout Croatia, most Rovinj accommodations (both hotels and sobe) prefer multinight stays—especially in peak season (July-Aug). While a few places levy surcharges for shorter stays, many are fine with even one-night stays (I’ve noted this in each listing). Don’t show up here without a room in August: Popular Rovinj is packed during that peak month.

All of these accommodations (with one exception) are on the Old Town peninsula, rather than the mainland section of the Old Town. Residence Dream is just around the atmospheric harbor, an easy five-minute walk away. Rovinj has no real hostel, but sobe are a good budget option.

$$$ Villa Markiz, run by Andrej with the help of eager-to-please Ivana, has four extremely mod, stylish apartments in an old shell in the heart of the Old Town. You’ll climb a steep and narrow staircase to reach the apartments, each of which has a small terrace (Db-€130/€80-100/€60). Only the gorgeous top-floor, two-story penthouse apartment has sea views (€250/€150-180/€140; no breakfast, air-con, free Wi-Fi, Pod Lukovima 1, tel. 052/841-380, Ivana mobile 099-652-7660, Andrej mobile 098-934-0321, dani7cro@msn.com).

$$$ Porta Antica rents 16 comfortable, nicely decorated apartments in five different buildings around the Old Town (all except La Carera are on the peninsula). Review your options on their website and be specific in your request (Db-€110-200/€90-170/€80-120, price depends on size and views, extra person-€25, no extra charge for 1-night stays, no breakfast, air-con, non-smoking, free Wi-Fi, reception and main building next door to TI on Obala Pina Budičina, mobile 099-680-1101, www.portaantica.com, portaantica@yahoo.it, Claudia).

$$$ Hotel Adriatic, a lightly renovated holdover from the communist days, features 27 rooms overlooking the main square, where the Old Town peninsula meets the mainland. The quality of the drab, worn rooms doesn’t justify the outrageously high prices...but the location might. Of the big chain of Maistra hotels (described on here), this is the only one in the Old Town (rates flex with demand, in top season figure Sb-€150, Db-€225; these prices are per night for 1- or 2-night stays—cheaper for 3 nights or more, all Sb are non-view, most Db have views—otherwise €20 less, no elevator, air-con, pay Wi-Fi, some nighttime noise—especially on weekends, Trg Maršala Tita, tel. 052/803-510, www.maistra.hr, adriatic@maistra.hr).

$$ Villa Cissa, run by Zagreb transplant Veljko Despot, has three apartments with tastefully modern, artistic decor above an art gallery in the Old Town. Kind, welcoming Veljko—who looks a bit like Robin Williams—is a fascinating guy who had an illustrious career as a rock-and-roll journalist (he was the only Eastern Bloc reporter to interview the Beatles) and record-company executive. Now his sophisticated, artistic style is reflected in these comfortable apartments. Because the place is designed for longer stays, you’ll pay a premium for a short visit (50 percent extra for 2-night stays, prices double for 1-night stays), and it comes with some one-time fees, such as for cleaning. But it’s worth the added expense. Veljko lives off-site, so be sure to clearly communicate your arrival time (smaller apartment-€108/€98/€88 plus €30 one-time cleaning fee, bigger apartment-€110 more plus €50 one-time cleaning fee, extra person-20 percent more, cash only, air-con, free Wi-Fi, lively café across the street, Zdenac 14, tel. 052/813-080, www.villacissa.com, info@villacissa.com).

$$ Casa Garzotto is an appealing mid-range option, with four apartments, four rooms, and one large family apartment in three different Old Town buildings. These classy and classic lodgings have modern facilities but old-fashioned charm, with antique furniture and historic family portraits on the walls. Thoughtfully run by a friendly staff, it’s a winner (rooms—Sb-€80/€80/€70, Db-€120/€105/€90; apartments—Db-€165/€140/€120; 2-bedroom family apartment—Db-€175/€150/€120, extra person-€25-30; includes breakfast, off-site parking, loaner bikes, and other thoughtful extras; 30 percent extra for 1-night stays, air-con, lots of stairs, free Wi-Fi in main building, reception and most apartments are at Garzotto 8, others are a short walk away, tel. 052/811-884, mobile 099-800-7338, www.casa-garzotto.com, casagarzotto@gmail.com).

$$ Trevisol Apartments has four new, modern units on a sleepy Old Town street, plus a few others around town. Check your options on their website, reserve your apartment, and arrange a time to meet (Db-€90/€75/€50; bigger seaview Db-€110/€80/€60; extra charge for 1-night stays: 50 percent in peak season, 30 percent off-season; no breakfast, air-con, free Wi-Fi, Trevisol 40, main office at Sv. Križa 33, mobile 098-177-7404, www.lvi.hr, Adriano).

$$ B&B Casale has three simple but affordable and nicely appointed rooms atmospherically located in a tight lane in the heart of the Old Town. As there’s no air-conditioning, thin windows, and lots of outdoor cafés nearby, it can be noisy at night (Db-€80/€55/€46, breakfast-€9/person, cash only, free Wi-Fi, Casale 2, tel. 052/814-828, mobile 099-888-5947, adr.cer@gmail.com, Adriano).

$$ Residence Dream, tucked in a tight warren of lanes in the touristy restaurant ghetto just around the harbor from the Old Town peninsula, has three modern, pleasantly furnished rooms above a busy restaurant. While you’re not right in the heart of the Old Town, it’s close enough, and it’s worth considering if other mid-range places are full (Db-€85/€75/€60, extra bed-€15, breakfast-60 kn, air-con, free Wi-Fi, good windows but may have some restaurant noise, Rakovca 18, tel. 052/830-613, mobile 091-579-9239, www.dream.hr, dream@dream.hr).

To escape the high prices of Rovinj’s Old Town, consider the resort neighborhood just south of the harbor. These are a 10- to 20-minute walk from the Old Town (in most cases, at least partly uphill), but most of that walk is along the very scenic harborfront—hardly an unpleasant commute. While the big Maistra hotels are an option, I prefer cheaper alternatives in the same area. Given the cost and inconvenience of parking if you’re sleeping in the Old Town (see “Arrival in Rovinj,” earlier, for details), accommodations in this area are handy for drivers. The big hotels are signposted as you approach town (follow signs for hoteli, then your specific hotel). Once you’re on the road to Hotels Eden and Park, the smaller ones are easy to reach: Villa Baron Gautsch is right on the road to Hotel Park; Hotel Vila Lili and Vila Kristina are a little farther on the main road toward Eden (to the left just after turnoff for Hotel Park, look for signs).

These are a bit closer to the Old Town than the Maistra hotels, and offer much lower rates and more personality. The first three are hotelesque and sit up on the hill behind the big resort hotels, while the last two choices lack personality but are a great budget option relatively close to the Old Town (an easy and scenic 10-minute walk).

$$ Villa Baron Gautsch, named for a shipwreck, is a German-owned pension with 17 bright, crisp, comfortable rooms and an inviting, shared view terrace (Db-€80/€70/€60, €10 more for balcony, they also have two Sb for half the Db price, no extra charge for 1-night stays, closed late Oct-Easter, cash only, air-con, no elevator, free Wi-Fi, free street parking, Ronjgova 7, tel. 052/840-538, www.baron-gautsch.com, baron.gautsch@gmx.net, Sanja).

$$ Hotel Vila Lili is a family-run hotel with 20 nicely decorated but slightly faded rooms above a restaurant on a quiet lane. While the rooms are pricey, the extra cost buys you more hotel amenities than the cheaper guest houses listed here (Sb-€65/€55, Db-€110/€100, pricier suites also available, no extra charge for 1-night stays, includes breakfast, elevator, air-con, free Wi-Fi, parking-35 kn/day, Mohorovičića 16, tel. 052/840-940, www.hotel-vilalili.hr, info@hotel-vilalili.hr, Petričević family).

$$ Vila Kristina, run by Kristina Kiš and her family, has 10 rooms and five apartments along a busy road. All but one of the units has a balcony. I’d skip the overpriced apartments (Db-€95/€85, apartment Db-€140/€120, no extra charge for 1-night stays, includes breakfast, air-con, no elevator, free Wi-Fi, Luje Adamovića 16, tel. 052/815-537, www.kis-rovinj.com, kristinakis@mail.inet.hr).

$ Elda Markulin, whose son runs the Baccus Wine Bar, rents three rooms and four apartments in a new, modern house a short walk up from the main harborfront road (Db-€50/€45/€40, apartment-€75/€60/€50, cash only, air-con, free Wi-Fi, Mate Balote 12, tel. 052/811-018, mobile 095-900-8654, markulin@hi.t-com.hr). To reach it from the Old Town, walk along the waterfront; after you pass the recommended Maestral restaurant and the ragtag boatyard on your right, turn left onto the uphill Mate Balote (just before the park).

$ Apartmani Tomo, next door to Elda (see directions above), is run with Albanian pride by Tomo Lleshdedaj, who rents seven rooms and nine studio apartments. While the lodgings are basic and communication can be a bit challenging, it’s a handy location for a budget last resort (Db-€50/€40/€35, Db with kitchen-€70/€60/€50, smaller studio Db-€75/€65/€55, bigger studio Db-€85/€75/€65, extra person-€10, cash only, air-con, free Wi-Fi, Mate Balote 10, tel. 052/813-457, mobile 091-578-1518, no email—reserve by phone).

The local hotel conglomerate, Maistra, has several hotels in the lush parklands just south of the Old Town. As all of the hotels were recently either completely renovated or built from scratch, these are a very expensive option; most of my readers—looking for proximity to the Old Town rather than hanging out at a fancy hotel—will prefer to save money and stay at one of my other listings. However, the Maistra hotels are worth considering if you can get a deal. These hotels have extremely slippery pricing, based on the type of room, the season, and how far ahead you book. (I’ve listed the starting rate for a 1- or 2-night stay in July-Aug; you’ll pay less if you stay longer or visit off-season. Complete rates are explained on the website, www.maistra.hr.) I’ve listed the hotels in the order you’ll reach them as you approach from the Old Town. All hotels have air-conditioning, elevators, free parking, and pay Wi-Fi, and include breakfast in their rates. The Maistra chain also has several other properties (including the Old Town’s Hotel Adriatic, described earlier; Hotel Katarina, a cheaper option with basic rooms picturesquely set on the small island facing the Old Town; and other more distant, cheaper options). Most Maistra hotels close during the winter.

$$$ Hotel Park is the humblest of the pack, with just three stars. It has 202 renovated but dull rooms in a colorized communist-era hull, and a seaside swimming pool with sweeping views to the Old Town. This is the handiest for walking into the Old Town—it’s a 10-minute stroll, entirely along the stunning harborfront promenade (Sb-€144, Db-€180, about €50 more for sea view, tel. 052/808-000, park@maistra.hr).

$$$ Hotel Monte Mulini is the fanciest of the bunch, with five stars, 99 rooms and 14 suites (all with seaview balconies), a beautiful atrium with a huge glass wall overlooking the cove, an infinity pool, and over-the-top prices (Db-€585, tel. 052/636-000, www.montemulinihotel.com, montemulini@maistra.hr).

$$$ Hotel Lone (LOH-neh), named for the cove it overlooks, is the newest and by far the most striking in the collection—the soaring atrium of this “design hotel” feels like a modern art museum. Also extremely expensive, its 248 rooms come wrapped in a vivid package (Db-€350, tel. 052/632-000, www.lonehotel.com, lone@maistra.hr).

$$$ Hotel Eden offers four stars and 325 upscale, imaginatively updated rooms with oodles of contemporary style behind a brooding communist facade (rates about €30 more than Hotel Park, tel. 052/800-400, eden@maistra.hr).

It’s expensive to dine in Rovinj, but the food is generally good, with a few truffle dishes on most menus (see “Istrian Food and Wine” sidebar on here). Interchangeable restaurants cluster where Rovinj’s Old Town peninsula meets the mainland, and all around the harbor. Be warned that most eateries—like much of Rovinj—close for the winter (roughly mid-Oct to Easter). If you’re day-tripping into the Istrian interior, consider dining at one of the excellent restaurants in or near Motovun (see here), then returning to Rovinj after dark.

(See “Rovinj” map, here.)

The easiest dining option is to stroll the Old Town embankment overlooking the harbor (Obala Pina Budičina), which changes its name to Svetoga Križa and cuts behind the buildings after a few blocks. Window-shop the pricey but scenic eateries along here, each of which has its own personality (all open long hours daily). Some have sea views, others are set back on charming squares, and still others have atmospheric interiors. I’ve listed these in the order you’ll reach them. You’ll pay top dollar, but the ambience is memorable.

Scuba, at the start of the row, is closest to the harbor—so, they claim, they get first pick of the daily catch from arriving fishing boats. They serve both seafood and tasty Italian dishes, in a contemporary interior or at outdoor tables with harbor views (70-80-kn pastas, 60-150-kn main dishes, daily 11:00-24:00, Obala Pina Budičina 6, mobile 098-219-446).

Veli Jože, with a smattering of outdoor tables (no real views) and a rollicking, folksy interior decorated to the hilt, is in all the guidebooks but still delivers on its tasty, traditional Istrian cuisine (50-80-kn pastas, 45-55-kn basic grill dishes, 110-160-kn main courses, daily 11:00-24:00, Sv. Križa 1, tel. 052/816-337).

Santa Croce, with tables scenically scattered along a terraced incline that looks like a stage set, is well-respected for its seafood and pastas. Classy and sedate, and with attentive service, it attracts a slightly older clientele (45-60-kn pastas, 70-150-kn main courses, no sea views, daily 18:00-23:00, Sv. Križa 11, tel. 052/842-240).

Lampo is simpler, with a basic menu of salads, pizzas, and pastas. The only reason to come here is for the fine waterfront seating at a reasonable price (45-65-kn pastas, 60-120-kn main courses, daily 11:00-24:00, Sv. Križa 22, tel. 052/811-186).

La Puntuleina, at the end of the row, is the most scenic (and most expensive) option. This upscale restaurant/wine bar features Istrian, Italian, and Mediterranean cuisine served in the contemporary dining room, or outside—either on one of the many terraces, or at tables scattered along the rocks overlooking a swimming hole. The menu is short, and Miriam and Giovanni occasionally add seasonal specials. As the outdoor seating is deservedly popular, reserve ahead (10-kn cover charge, 80-110-kn pastas, 120-180-kn main courses, daily 12:00-23:00, closed Nov-Easter, on the Old Town embankment past the harbor at Sv. Križa 38, tel. 052/813-186). You can also order just a drink to sip while sitting down on the rocks.

Just before La Puntuleina, don’t miss the inviting Valentino Champagne and Cocktail Bar—with no food but similar “drinks on the rocks” ambience (described earlier, under “Nightlife in Rovinj”). If you’re on a tight budget, dine cheaply elsewhere, then come here for an after-dinner finale.

(See “Rovinj” map, here.)

Offering upscale, international (rather than strictly Croatian) food and presentation, these options are expensive but creative.

Monte Restaurant is your upscale, white-tablecloth splurge—made to order for a fine dinner out. With tables strewn around a covered terrace just under the town bell tower, this atmospheric place features inventive cuisine that melds Istrian products with international techniques. Come here only if you value a fine dining experience, polished service, and the chance to learn about local food and wines without regard for price (plan to spend 350-700 kn per person for dinner, daily 12:00-14:30 & 18:30-23:00, reserve ahead in peak season, Montalbano 75, tel. 052/830-203, Ðekić family).

Krčma Ulika, a classy hole-in-the-wall run by Inja Tucman, has a mellow, cozy, art-strewn interior. Inja enjoys surprising diners with unexpected flavor combinations. The food is a bit overpriced and can be hit-or-miss, but the experience feels like an innovative break from traditional Croatian fare. As portions are small (Inja encourages diners to order two courses), the price can add up (15-kn cover, 80-100-kn starters and pastas, 180-200-kn main courses, daily 13:00-15:00 & 19:00-24:00—except closed for lunch in Aug, closed mid-Oct-April, cash only, Porečka 6, tel. 052/818-089, mobile 098-929-7541).

(See “Rovinj” map, here.)

These options are a bit less expensive than most of those described above. I’ve listed them in the order you’ll reach them as you walk around Rovinj’s harbor.

Maestral combines affordable, straightforward pizzas and seafood with Rovinj’s best view. If you want an outdoor table overlooking bobbing boats and the Old Town’s skyline—without breaking the bank—this is the place. It fills a big building surrounded by workaday shipyards about a 10-minute walk from the Old Town, around the harbor toward Hotel Park (35-45-kn sandwiches, 45-60-kn pizzas and pastas, 50-100-kn fish and meat dishes, daily 9:00-24:00, closed Oct-March, obala N. Nazora b.b., look for Bavaria beer sign, tel. 052/830-565).

Sidro, around the harbor with views back on the Old Town, has a typical menu of pasta, pizza, and fish. But it’s particularly well-respected for its Balkan meat dishes such as ćevapčići (see the “Balkan Flavors” sidebar on here) and a spicy pork-and-onion stew called mućkalica. With unusually polite service and a long tradition (run by three generations of the Paoletti family since 1966), it’s a popular local hangout (45-75-kn pastas, 55-90-kn grilled meat dishes, 110-140-kn steaks and fish, daily 11:00-23:00, closed Nov-Feb, harborfront at Rismondo 14, tel. 052/813-471).

Gostionica/Trattoria Toni is a hole-in-the-wall serving up small portions of good Istrian and Venetian fare. Choose between the cozy interior (tucked down a tight lane), or the terrace on a bustling, mostly pedestrian street (40-95-kn pastas, 40-140-kn main courses, daily 12:00-15:00 & 18:00-22:30, just up ulica Driovier on the right, tel. 052/815-303).

(See “Rovinj” map, here.)

Most rental apartments come with a kitchenette handy for breakfasts (stock up at a neighborhood grocery shop). Cafés and bars along the waterfront serve little more than an expensive croissant with coffee. The best budget breakfast (and a fun experience) is a picnic. Within a block of the market, you have all the necessary stops: the Brionka bakery (fresh-baked cheese or apple strudel); mini-grocery stores (juice, milk, drinkable yogurt, and so on); market stalls (cherries, strawberries, walnuts, and more, as well as an elegant fountain for washing); an Albanian-run bread kiosk, Pekarna Laste, between the market and the water...plus benches with birds chirping, children playing, and fine Old Town views along the water. For a no-fuss alternative, you can shell out 60 kn for the buffet breakfast at Hotel Adriatic (daily 7:00-10:00, until 11:00 July-Aug; described earlier, under “Sleeping in Rovinj”).

Rovinj’s bus station is open daily 6:30-9:15 & 9:45-16:30 & 17:00-21:30. As always, confirm the following times before planning your trip. Bus schedules are dramatically reduced on Saturdays and especially on Sundays, as well as (in some cases) off-season. Bus information: Tel. 060-333-111 or 052/811-453, www.autobusni-kolodvor.com.

From Rovinj by Bus to: Pula (about hourly, 45 minutes), Poreč (3-6/day, 1 hour), Rijeka (4-5/day, 2-3.5 hours), Zagreb (6-9/day, 3-6 hours), Venice (1/day Mon-Sat departing very early in the morning—likely at 5:40, arriving Venice at 10:00, none Sun).

To Slovenia: In the summer, two daily buses connect Rovinj to Slovenia (Piran and Ljubljana): a slow one departing at 8:00 (3 hours to Piran, 5.5 hours to Ljubljana, late June-Aug only) or an express one departing at around 16:35 (2 hours to Piran, 4 hours to Ljubljana, July-Sept only); as this connection changes from year to year, confirm schedules at www.ap-ljubljana.si. Twice weekly off-season (generally Mon and Fri), an early morning bus begins in Pula, then heads to Poreč, Portorož (with an easy transfer to Piran), and Ljubljana. You can also reach Piran (and other Slovenian destinations) with transfers in Umag and Portorož.

To the Dalmatian Coast: A bus departs Rovinj every evening at 19:00 for the Dalmatian Coast, arriving in Split at 6:00 and Dubrovnik at 11:00. (If this direct bus isn’t running, you can take an earlier bus to Pula, from where this night bus leaves at 20:00; also note that Pula has two daytime connections to Split.)

Just north of Rovinj, on the coastal road to Poreč, you’ll drive briefly along a seven-mile-long inlet dubbed the Limski Canal (Limski Kanal—sometimes called “Limski Fjord”...but only to infuriate Norwegians). Named for the border (Lim-it) between Rovinj and Poreč, this jagged slash in the landscape was created when an underground karstic river collapsed. Keen-eyed arborists will notice that the canal’s southern bank has deciduous trees, and the northern bank, evergreens. Many Venetian quarries once pulled stone from the walls of this canal to build houses and embankments. Supposedly the famed pirate Captain Morgan was so enchanted by this canal that he retired here, founding the nearby namesake town of Mrgani. Local tour companies sell boat excursions into the fjord, which is used to raise much of the shellfish that’s slurped down at local restaurants. While the canal isn’t worth going out of your way to see, you may skirt it anyway. Along the road above the canal, you’ll pass kiosks selling grappa (firewater, a.k.a. rakija), honey, and other homemade concoctions. The recommended Matošević winery is a two-minute drive away (see here).

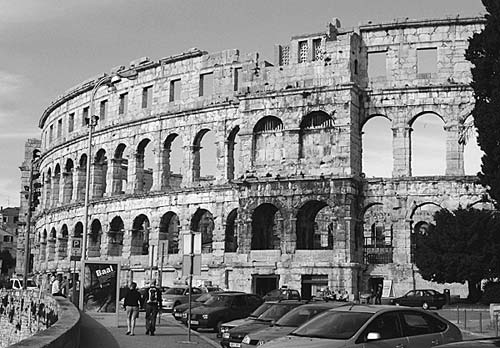

Pula (POO-lah, Pola in Italian) isn’t quaint. Istria’s biggest city is an industrial port town with traffic, smog, and sprawl...but it has the soul of a Roman poet. Between the shipyards, you’ll discover some of the top Roman ruins in Croatia, including a stately amphitheater—a fully intact mini-Colosseum that marks the entry to a seedy Old Town with ancient temples, arches, and columns.

Strategically situated at the southern tip of the Istrian Peninsula, Pula has long been a center of industry, trade, and military might. In 177 B.C., the city became an important outpost of the Roman Empire. It was destroyed during the wars following Julius Caesar’s death and rebuilt by Emperor Augustus. Many of Pula’s most important Roman features—including its amphitheater—date from this time (early first century A.D.). But as Rome fell, so did Pula’s fortunes. The town changed hands repeatedly, caught in the crossfire of wars between greater powers—Byzantines, Venetians, and Habsburgs. After being devastated by Venice’s enemy Genoa in the 14th century, Pula gathered dust as a ghost town...still of strategic military importance, but otherwise abandoned.

In the mid-19th century, Italian unification forced the Austrian Habsburgs—whose navy had been based in Venice—to look for a new home for their fleet. In 1856, they chose Pula, and over the next 60 years, the population grew thirtyfold. (Despite the many Roman and Venetian artifacts littering the Old Town, most of modern Pula is essentially Austrian.) By the dawn of the 20th century, Pula’s harbor bristled with Austro-Hungarian warships, and it had become the crucial link in a formidable line of imperial defenses that stretched from here to Montenegro. As one of the most important port cities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Pula attracted naval officers, royalty...and a young Irishman named James Joyce who was on the verge of revolutionizing the literary world.

Today’s Pula, while no longer quite so important, remains a vibrant port town and the de facto capital of Istria. It offers an enjoyably urban antidote to the rest of this stuck-in-the-past peninsula.

Pula’s sights, while top-notch, are quickly exhausted. Two or three hours should do it: Visit the amphitheater, stroll the circular Old Town, and maybe see a museum or two. As it’s less than an hour from Rovinj, there’s no reason to spend the night.

Although it’s a big city, the tourist’s Pula is compact: the amphitheater and, beside it, the ring-shaped Old Town circling the base of an old hilltop fortress. The Old Town’s main square, the Forum, dates back to Roman times.

Pula’s TI overlooks the Old Town’s main square, the Forum. It offers a free map and information on the town and all of Istria (daily June-Sept 8:00-21:00—or until 22:00 in July-Aug, May and Oct 8:00-18:00, Nov-April 9:00-16:00, Forum 3, tel. 052/219-197, www.pulainfo.hr).

By Car: Pula is about a 45-minute drive south of Rovinj. Approaching town, follow Centar signs, then watch for the amphitheater. Parking is plentiful on the streets around the amphitheater; if it’s parked up, head for the large pay lot just below the amphitheater, toward the waterfront. This lot, and any street spaces marked in blue, cost the same (4 kn/hour; if parking on street, pay at meter or buy parking voucher at newsstand to display in window).

By Bus: As you exit the bus station, walk toward the yellow mansion, then turn left onto the major street (ulica 43 Istarske Divizije); at the roundabout, bear left again, and you’ll be headed for the amphitheater (about a 10-minute walk total).

By Train: The train station is a 15-minute walk from the amphitheater, near the waterfront (in the opposite direction from the Old Town). Walk with the coast on your right until you see the amphitheater.

By Plane: Pula’s small airport, which is served by various low-cost airlines, is about 3.5 miles northeast of the center. A handy and affordable shuttle bus is coordinated to depart 20 minutes after many budget flights arrive—check for details with your airline (30 kn to downtown Pula, 90 kn to Rovinj, run by two different companies—check schedule and prebook at www.brioni.hr or www.fils.hr). Public bus #23 goes between the airport and Pula’s bus station, but it’s infrequent (10/day Mon-Fri, 4/day Sat, none Sun) and stops along the road in front of the airport rather than at the airport itself (coming from town to the airport, watch for buses to Valtura). The fair rate for a taxi into downtown Pula is about 80 kn, but most manage to charge more like 100 kn (don’t pay more than that). Airport info: Tel. 052/530-105, www.airport-pula.com.

Car Rental: All of the big rental companies have their offices at the airport (see airport info above); the TI has a list of a few local outfits with offices downtown.

Local Guide: If you’d like a guide to help you uncover the story of Pula, Mariam Abdelghani leads great tours of the major sites (€80 for a 2-hour city tour, €160 for an all-day tour of Istria, mobile 098-419-560, mariam.abdelghani@gmail.com).

(See “Pula” map, here.)

This walk is divided between Pula’s two most interesting attractions: the Roman amphitheater and the circular Old Town. About an hour for each is plenty. More time can be spent sipping coffee al fresco or dipping into museums.

• Begin at Pula’s main landmark, its...

Of the dozens of amphitheaters left around Europe and North Africa by Roman engineers, Pula’s is the sixth-largest (435 feet long and 345 feet wide) and one of the best-preserved anywhere. This is the top place in Croatia to resurrect the age of the gladiators.

Cost and Hours: 40 kn, daily May-Sept 8:00-21:00—often later in July-Aug and for special events, April 8:00-20:00, Oct 9:00-19:00, Nov-March 9:00-17:00. The 30-kn audioguide, available at the kiosk inside, narrates 20 stops with 30 minutes of flat, basic data on the structure.

Gladiator Shows: About once each week in the summer, costumed gladiators re-enact the glory days of the amphitheater in a show called Spectacvla Antiqva (60 kn, 1/week late June-mid-Sept, details at www.pulainfo.hr).

Self-Guided Tour: Go inside and explore the interior, climbing up the seats as you like. An “amphi-theater” is literally a “double theater”—imagine two theaters, without the back wall behind the stage, stuck together to maximize seating. Pula’s amphitheater was built over several decades (first century A.D.) under the reign of three of Rome’s top-tier emperors: Augustus, Claudius, and Vespasian. It was completed around A.D. 80, about the same time as the Colosseum in Rome. It remained in active use until the beginning of the fifth century, when gladiator battles were outlawed. The location is unusual but sensible: It was built just outside town (too big for tiny Pula, with just 5,000 people) and near the sea (so its giant limestone blocks could be transported here more easily from the quarry six miles away).

Self-Guided Tour: Go inside and explore the interior, climbing up the seats as you like. An “amphi-theater” is literally a “double theater”—imagine two theaters, without the back wall behind the stage, stuck together to maximize seating. Pula’s amphitheater was built over several decades (first century A.D.) under the reign of three of Rome’s top-tier emperors: Augustus, Claudius, and Vespasian. It was completed around A.D. 80, about the same time as the Colosseum in Rome. It remained in active use until the beginning of the fifth century, when gladiator battles were outlawed. The location is unusual but sensible: It was built just outside town (too big for tiny Pula, with just 5,000 people) and near the sea (so its giant limestone blocks could be transported here more easily from the quarry six miles away).

Notice that the amphitheater is built into the gentle incline of a hill. This economical plan, unusual for Roman amphitheaters, saved on the amount of stone needed, and provided a natural foundation for some of the seats (notice how the upper seats incorporate the slope). It may seem like the architects were cutting corners, but they actually had to raise the ground level at the lower end of the amphitheater to give it a level foundation. The four rectangular towers anchoring the amphitheater’s facade are also unique (two of them are mostly gone). These once held wooden staircases for loading and unloading the amphitheater more quickly—like the massive corkscrew ramps in many modern stadiums. At the top of each tower was a water reservoir, used for powering fountains that sprayed refreshing scents over the crowd to mask the stench of blood.

And there was plenty of blood. Imagine this scene in the days of the gladiators. More than 25,000 cheering fans from all social classes filled the seats. The Romans made these spectacles cheap or even free—distracting commoners with a steady diet of mindless entertainment prevented discontent and rebellion. (Hmm...The Voice, anyone?) Canvas awnings rigged around the top of the amphitheater shaded many seats. The fans surrounded the “slaying field,” which was covered with sand to absorb blood spilled by man and beast, making it easier to clean up after the fight. This sand (harena) gave the amphitheater its nickname...arena.

The amphitheater’s “entertainers” were gladiators (named for the gladius, a short sword that was tucked into a fighter’s boot). Some gladiators were criminals, but most were prisoners of war from lands conquered by Rome, who dressed and used weapons according to their country of origin. A colorful parade kicked off the spectacle, followed by simulated fights with fake weapons. Then the real battles began. Often the fights represented stories from mythology or Greek or Roman history. Most ended in death for the loser. Sometimes gladiators fought exotic animals—gathered at great expense from far corners of the empire—which would enter the arena from the two far ends (through the biggest arches). There were female gladiators, as well, but they always fought other women.

While the life of a gladiator seems difficult, consider that it wasn’t such a bad gig—compared to, say, being a soldier. Gladiators were often better paid than soldiers, enjoyed terrific celebrity (both in life and in death), and only had to fight a few times each year.

Ignore the modern seating, and imagine when the arena (sandy oval area in the center) was ringed with two levels of stone seating and a top level of wooden bleachers. Notice that the outline of the arena is marked by a small moat (now covered with wooden slats)—just wide enough to keep the animals off the laps of those with the best seats, but close enough so that blood still sprayed their togas.

After the fall of Rome, builders looking for ready-cut stone picked apart structures like this one—scraping it as clean as a neat slice of cantaloupe. Sometimes the scavengers were seeking the iron hooks that were used to connect the stone; in those oh-so “Dark Ages,” the method for smelting iron from ore was lost. Most of this amphitheater’s interior structures—such as steps and seats—are now in the foundations and walls of Pula’s buildings...not to mention palaces in Venice, across the Adriatic. In fact, in the late 16th century, the Venetians planned to take this entire amphitheater apart, stone by stone, and reassemble it on the island of Lido on the Venetian lagoon. A heroic Venetian senator—still revered in Pula—convinced them to leave it where it is.

Despite these and other threats, the amphitheater’s exterior has been left gloriously intact. The 1999 film Titus (with Anthony Hopkins and Jessica Lange) was filmed here, and today the amphitheater is still used to stage spectacles—from Placido Domingo to Elton John—with seating for about 5,000 fans. Recently, the loudest concerts were banned, because the vibrations were damaging the old structure.

Before leaving, don’t miss the museum exhibit (in the “subterranean hall”—follow exhibition signs down the chute marked #17). This takes you to the lower level of the amphitheater, where gladiators and animals were kept between fights. When the fight began, gladiators would charge up a chute and burst into the arena, like football players being introduced at the Super Bowl. As you go down the passage, you’ll walk on a grate over an even lower tunnel. Pula is honeycombed with tunnels like these, originally used for sewers and as a last-ditch place of refuge in case of attack. Inside, the exhibit—strangely dedicated to “olive oil and wine production in Istria” instead of, you know, gladiators—is surprisingly interesting. Browse the impressive collection of amphorae (see sidebar), find your location on the replica of a fourth-century A.D. Roman map (oriented with east on top), and ogle the gigantic grape press and two olive-oil mills.

On your way out, check the corridor across from the ticket booth to see if there are any temporary exhibits.

• From the amphitheater, it’s a few minutes’ walk to Pula’s Old Town, where more Roman sights await. Exit the amphitheater, cross the street, turn left, and walk one long block along the small wall up the busy road (Amfiteatarska ulica). When you reach the big park on your right, look for the little, car-sized...

Use this handy model of Pula to get oriented. Next to the amphitheater, the little water cannon spouting into the air marks the pale-blue house nearby, the site of a freshwater spring (which makes this location even more strategic). The big star-shaped fortress on the hill is Fort Kaštel, designed by a French architect during the Venetian era (1630). Read the street plan of the Roman town into this model: At the center (on the hill) was the castrum, or military base. At the base of the hill (the far side from the amphitheater) was the forum, or town square. During Pula’s Roman glory days, the hillsides around the castrum were blanketed with the villas of rich merchants. The Old Town, which clusters around the base of the fortress-topped hill, still features many fragments of the Roman period, as well as Pula’s later occupiers. We’ll take a counterclockwise stroll around the fortified old hill through this ancient zone.

The huge anchor across the street from the model celebrates Pula’s number-one employer—its shipyards.

• Continue along the street. At the fork, bear right (on Kandlerova ulica—level, not uphill). Notice the Roman ruins on your right. Just about any time someone wants to put up a new building, they find ruins like these. Work screeches to a halt while the valuable remains are excavated. In this case, they’ve discovered three Roman houses, two churches, and 2,117 amphorae—the largest stash found anywhere in the world. (The harbor is just behind, which suggests this might have been a storehouse for off-loaded amphorae.) I guess the new parking garage has to wait.

After about three more blocks strolling through gritty, slice-of-life Pula, on your right-hand side, you’ll see Pula’s...

This church combines elements of the two big Italian influences on Pula: Roman and Venetian. Dating from the fifth century A.D., the Romanesque core of the church (notice the skinny, slitlike windows) marks the site of an early-Christian seafront settlement in Pula. The Venetian Baroque facade and bell tower are much more recent (early 18th century). Typical of the Venetian style, notice how far away the austere bell tower is from the body of the church. The bell tower’s foundation is made of stones that were scavenged from the amphitheater. The church’s sparsely decorated interior features a classic Roman-style basilica floor plan, with a single grand hall—the side naves were added in the 15th century, after a fire.

Cost and Hours: Free, generally open daily 10:00-18:00 in summer, less off-season.

• Keep walking through the main pedestrian zone, past all the tacky souvenir shops and Albanian-run fast-food and ice-cream joints. After a few more blocks, you emerge into the...

Every Roman town had a forum, or main square. Twenty centuries later, Pula’s Forum not only serves the same function but has kept the old Roman name.

Two important buildings front the north end of the square, where you enter. The smaller building (on the left, with the columns) is the first-century A.D. Roman Temple of Augustus (Augustov Hram). Built during the reign of, and dedicated to, Augustus Caesar, this temple took a direct hit from an Allied bomb in World War II. After the war, the Allied occupiers rebuilt it as a sort of mea culpa—notice the patchwork repair job. It’s the only one remaining of three such temples that once lined this side of the square. Inside the temple is a single room with fragments of ancient sculptures (10 kn, May-Sept Mon-Sat 9:00-20:00, Sun 10:00-15:00, often closed Oct-April, sparse English labels). The surviving torso from a statue of Augustus, which likely stood on or near this spot, dates from the time of Christ. Other evocative chips and bits of Roman Pula include the feet of a powerful commander with a pathetic little vanquished barbarian obediently at his knee (perhaps one of the Histri—the indigenous Istrians that the Romans conquered in 177 B.C.).