Map: Sarajevo Self-Guded Walk Old Town Section

▲▲Sniper Alley: The Siege of Sarajevo

Map: Sarajevo Hotels & Restaurants

Route Tips for Drivers: From Mostar to Sarajevo

Spectacularly set in a mountain valley blanketed with cute Monopoly houses, Sarajevo (sah-rah-YEH-voh) is a sight to behold. It’s a cruel irony that for a few short years, Sarajevo became synonymous with sectarian strife, because for virtually its entire history, this beautiful city was a model of the opposite: Muslims, Catholics, Orthodox Christians, and Jews living together in cooperation and harmony. (One of its many nicknames is “Little Jerusalem.”) Squeezed into its narrow valley, Sarajevo never even had the option of splitting itself up into ethnic ghettos, so people lived side-by-side. To this day, there are several places in the city where you can see a mosque, synagogue, Catholic church, and Orthodox church with a turn of the head.

Sarajevo is the delightful product of a rich, if occasionally tumultuous, history. The Ottoman-style Old Town, the Baščaršija, feels transplanted here from Istanbul. Then you’ll turn a corner and suddenly feel lost in an almost Viennese cityscape. Strolling its streets is the next best thing to a time machine.

Though torn by war two decades ago, Sarajevo is now a comfortable and safe place to visit. Listen to the Muslim call to prayer and Catholic and Orthodox church bells playfully jostle above the characteristic cobbled lanes. Step into historic houses of worship from each of this region’s four major faiths, watching for similarities. Visit the street corner where World War I began, climb up into the hills to the Olympic stadium that commanded the world’s attention in 1984, or ascend even higher for sweeping views over one of Europe’s most stunningly set capitals. Make friends with a gregarious Sarajevan—it’s easy to do—and ask him the best way to prepare and drink Bosnian coffee. Ponder the scars of war, hunch over to squeeze through the tunnel that was the besieged Sarajevans’ lifeline to the world, and listen to a local relate personal stories from the harrowing time of the siege. Play a game of giant chess with the jeering old-timers in an urban park. Shop your way through the copper-laden canyons of the Turkish-style bazaar, bartering down the price of a hand-hammered Bosnian coffee set. Relax in a hidden caravanserai, take a slow drag on a šiša (water pipe spewing sweet plumes of fruity smoke), and sample some honey-dripping pastry treats. For dinner—or just a snack—nibble on some of the best bureks (savory, flaky pies) and ćevapi (grilled sausages) this side of the Bosphorus. Go ahead—it’s OK to enjoy Sarajevo.

Sarajevo demands a minimum of a day. Side-tripping here from Mostar lets you scratch the surface, but you won’t regret having one, two, or even three nights here. With whatever time you have, begin in the characteristic Turkish quarter, the Baščaršija.

I’ve described two self-guided walks. If you only have time for one, take the first one, which provides a good orientation to Sarajevo and takes you all the way through town, with opportunities to stop at virtually all of the important sights (except the Sarajevo War Tunnel Museum, which requires a long but worthwhile detour). The second walk focuses on the urban, “downtown” zone called “Sniper Alley,” with some harrowing tales of the Siege of Sarajevo.

Note that Sarajevo is a 2.5-hour trip beyond Mostar, making it a logistical deadhead that’s not really “on the way” to other destinations in this book. To maximize efficient use of your time, consider flying in or out of here (for example, Croatia Airlines has reasonably priced flights to Zagreb). But be aware that in winter, heavy morning fog often grounds flights.

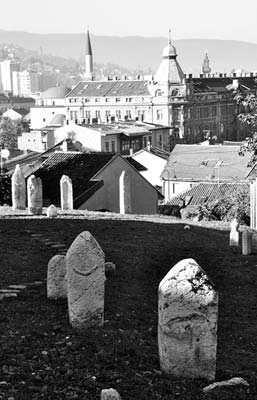

With approximately 310,000 people (660,000 in the greater Sarajevo area)—filling a city that held up to 525,000 at its prewar peak—Sarajevo is barely contained by its valley. It’s surrounded by steep mountains on all sides, with its houses scampering up the valley walls (more recently joined by wartime cemeteries occupying what once were forested parks). It’s a long, skinny city, lining up along its humble Miljacka River and main thoroughfare. You can trace the city’s historical and architectural development from east to west, starting with the historic Old Town core, called the Baščaršija. West of that is the Austrian-feeling part of town (along Ferhadija street), and beyond that, the modern, concrete skyscraper zone called Marijin Dvor. From here, the city’s busy main drag rumbles west (it’s called Zmaja od Bosne close to downtown, and Bulevar Meše Selimovića farther out; in wartime it was known as “Sniper Alley”).

Terminology: When it comes to the wars of the 1990s, the terminology for the various parties is particularly sensitive—and can vary depending on who you’re talking to. During the siege, the citizens of Sarajevo were majority Muslim/Bosniak, but also included Croats, Serbs, Jews, and others; many think of themselves not as a specific ethnicity, but as “Sarajevans” or “Bosnians.” Meanwhile, the army surrounding the city was made up almost entirely of Serbs, but not all Serbs supported them—so to call them simply “Serbs” is incomplete. Sarajevans (conscientious not to disrespect the many Serbs who were among those besieged) prefer to call the aggressors “the Bosnian Serb Army,” “Army of Republika Srpska” (abbreviated VRS), “Karadžić’s forces,” or “Četniks.” But the term “Četnik” is a loaded one: It was first used to describe the fierce Serb fighting force that ethnically cleansed parts of Yugoslavia during World War II. The troops who surrounded the city evoked this earlier image and called themselves “Četniks,” and many Sarajevans have followed suit. However, in other contexts, calling a Serb (who was not involved in the siege) a “Četnik” is a serious insult that could put you on the receiving end of the infamous Balkan temper. It’s similar to calling an everyday German a “Nazi”: The rare German who actually has Nazi sympathies may consider it a badge of honor, but the vast majority would be justifiably hurt and angry.

Anniversary: The year 2014 is a big one in Sarajevo, as it marks both the centennial of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which sparked the beginning of World War I (an international peace conference is planned to coincide with the anniversary); and the 30-year anniversary of the 1984 Sarajevo Olympics.

Sarajevo’s helpful TI is on the main pedestrian drag through the old Ottoman quarter (May-Aug Mon-Fri 9:00-22:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-18:00; Sept-April Mon-Fri 10:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-16:00; Sarači 58, tel. 033/580-999, www.sarajevo-tourism.com). Another branch is at the airport. At either TI, you can pick up maps of town, the Sarajevo Navigator monthly planner, and other brochures.

By Bus or Train: Sarajevo’s bus and train stations sit next to each other one very long, urban block up from the Marijin Dvor area (former “Sniper Alley,” US Embassy, Holiday Inn, and museums).

The train station looks out over a desolate-feeling plaza; simply walk out front, buy a tram ticket from the kiosk, and ride tram #1 to the Baščaršija (the Old Town, with my recommended hotels). Alternatively, you can pay 6-10 KM for a taxi, or you can walk: Across the street and to the right, you’ll see the very long, imposing wall of the US Embassy. If you walk along this wall straight ahead, you’ll pop out near the Holiday Inn and “Sniper Alley.”

The bus station (Autobusna Stanica Sarajevo) has a small ticket lobby, a left-luggage desk (garderoba), and a smattering of kiosks and cafés. Exit the building straight ahead, keeping the busy street on your right. Walk about 100 yards, then hook left around the big post office (near a row of cafés). You’ll wind up at the big plaza in front of the train station, with the stop for tram #1 (explained above).

By Car: If you’re driving into Sarajevo from Mostar, see “Route Tips for Drivers” at the end of this chapter.

By Plane: Sarajevo’s small, sleepy airport sits on the southwestern edge of town (airport code: SJJ, tel. 033/289-100, www.sarajevo-airport.ba). It has ATMs and a TI kiosk. Unfortunately, there’s no handy public-transportation connection into town, so the easiest option is a taxi; the fair metered rate to downtown is around 15-20 KM, but most taxi drivers demand 30 KM. If you’d like to take public transit, walk straight out the front door of the airport and continue on foot about 10 minutes directly ahead to the Dobrinja neighborhood, where you can catch trolley bus #103 to the Latin Bridge in the Old Town, or bus #31E to near the old City Hall, also in the Old Town (both run about 3-4/hour, buy ticket from kiosk or driver, see tram description, next). If you’ll be at the airport, it’s convenient to visit the nearby War Tunnel Museum (pay no more than 10 KM for the taxi ride from the airport).

Almost everything that’s worth seeing in town (with the notable exception of the War Tunnel Museum) is within long walking distance of each other. But you may need to make use of the city’s public transportation network, which includes trams, buses, and trolley buses. A single ticket costs 1.60 KM if you buy it at a kiosk, or 1.80 KM if you buy it on board (good for one ride only—if you transfer, you must buy a new ticket; when boarding, validate your ticket by stamping it in the green box). A day ticket for 5 KM is good for one calendar day (sold only at the kiosk behind the Catholic cathedral). The handy tram #3 does a big loop from one end of town to the other, starting in the Old Town (several stops, including at the Latin Bridge/Latinska Ćuprija, at the City Hall/Vijećnica, at the Baščaršija stop near the main square on Kovači street, and behind the cathedral), then along the main drag (former “Sniper Alley”) to the west end of town (Ilidža stop, a short taxi ride to the Sarajevo War Tunnel Museum), and back again (7.5 miles and 40 minutes one-way). Tram #1 is also useful, connecting the train and bus stations with “Sniper Alley” and the Old Town.

Travel Agency: Sirius Travel, run by can-do Bakir and Sakiba Zagorica (who used to live in Florida), can arrange accommodations and transfers (€10 to the airport), tours around town (€50/2-hour walking tour, €80/4-hour walking tour plus drive to panoramic viewpoints), or anything else you might need in Sarajevo (along the river at Obala Kulina Bana 5, tel. 033/550-940, www.sirius-travel.ba, siriustravel@bih.net.ba).

Internet Access: You’ll find Internet cafés all over the Old Town. Wi-Fi is widely available at hotels and cafés; look for the free “old city” Wi-Fi hotspot around “Pigeon Square.”

With such a powerful and challenging-to-grasp recent history, and with the ready availability of extremely good and affordable local guides, it’s virtually obligatory to hire a guide for your Sarajevo time. For the price of joining an organized walking tour in many European cities, you can hire your very own Sarajevan for the day, who will likely be willing to speak frankly about their experiences during the siege. If at all possible, arrange to hire Amir Telibečirović, a journalist, war veteran, and historian who explains Sarajevo’s sights and history—from ancient to recent—with brilliant clarity. Amir can add immeasurably to your Sarajevo experience (30 KM or €15/person for a tour of any length, or 50 KM/€25 for just one person, mobile 061-304-966, teleamir@gmail.com). If Amir is busy, Jadranka Šuster is worth considering for her professional, by-the-book approach (€40/2 hours, €15/extra hour, €120/all day, more for 4 or more people; also offers special activities such as cooking classes, gastronomic tours, coppersmithing, and wood-burning crafts; mobile 061-828-400, www.sarajevo-tour.com, sarajevotour@gmail.com). Other guides are also available for similar rates; to arrange, contact Sirius Travel (see “Helpful Hints,” earlier).

This company runs various itineraries around the city, departing from their office near the Latin Bridge (at Zelenih Beretki 30, open Mon-Fri 8:00-18:00—or until 17:00 in winter, Sat-Sun 9:30-14:00). Options include their introductory free tour (tips expected, 1.5 hours, daily at 16:30); Times of Misfortune, detailing the siege (€27, includes entrance to War Tunnel Museum, 3 hours, daily at 11:00); a tour of the War Tunnel Museum (€15, includes museum admission, 2 hours, daily at 14:00); a food tour called “Eat, Pray, Love” (€30, 4 hours, daily at 10:00); and other tours available on request (such as their Jewish tour, €25, 4 hours; and their Grand Tour, €30, 4 hours). They also offer excursions to other parts of Bosnia (including the Srebrenica massacre site, a river-rafting trip, Mostar, and the Bosnian pyramid). Call ahead to reserve and confirm the details (mobile 061-190-591, tel. 033/534-353, www.sarajevoinsider.com). Their office also has a modest museum about the Siege of Sarajevo, with an eight-minute film and exhibits outlining a brief rundown of the history (3 KM).

Sarajevo’s spectacular setting lends itself to adventure travel—hiking, mountain biking, river rafting, skiing, and so on. Green Visions offers eco-friendly excursions into the Bosnian countryside (tel. 033/717-291, www.greenvisions.ba).

Below I’ve outlined two different walks that, when taken together, provide a useful spine for visiting virtually all of the sights mentioned under “Sights in Sarajevo,” later (except the War Tunnel Museum, which is farther out). The first walk covers the historic core of town, including most of the museums. The second (which begins an easy 10-minute walk from where the first leaves off) focuses on the Siege of Sarajevo.

(See “Sarajevo Self-Guided Walk Old Town Section” map, here.)

This walk begins where most tourist visits do, in the Ottoman-influenced Old Town—the Baščaršija—then strolls through history as it traverses the Habsburg quarter. Architecturally, it moves more or less forward through history (though the sights jump around a bit).

I’ve split the walk into three parts. If you’re in a hurry and want to focus on the Old Town, you can just do Parts 1 and 2; Part 3 takes you deeper into the urban part of town, including some sights relating to the siege, and is worthwhile if you can spare the time. Doing the entire walk without entering any of the sights could take as little as two hours—but with sightseeing stops, it can fill an entire day or more.

• Begin at the main square of the Old Town (Baščaršija), with the wooden fountain at the top.

“Pigeon Square”: Though it’s nicknamed for its many winged residents, this square is officially called Baščaršija. Literally translated as “Main Marketplace,” this unmistakably Ottoman-flavored square has given its name to the entire Old Town. The fountain (notice the small faucet at the base), called Sebilj, is an icon of Sarajevo. According to local legend, visitors who drink water from this fountain will return to Sarajevo someday. The original was built in 1753, but this restored version dates from the 19th century. Although it’s the centerpiece of the “Turkish” Old Town, the fountain is more Persian in style. The Ottoman Empire (of which Sarajevo was a part) enjoyed influences from throughout both the Islamic and the European worlds: art, literature, and poetry from Persia (today’s Iran); religious influence (i.e., Sunni Islam) from the Arabic world; diplomacy from the Germanic world; and herbal pharmacology and music from the Jewish world.

Turn with your back to the fountain and walk down the cobbled square. Look for the tight little lane on the left, just before the mosque. This is the wonderfully authentic Coppersmiths’ Street (Kazandžiluk), where craftsmen still carry out their work, hammering beautiful works of art out of copper—you can hear their little hammers tapping from their workshops. It’s just the place to buy a copper Bosnian coffee set that you’ll never use. This might be the most touristy street in Sarajevo, so the prices aren’t a bargain, but it’s a fun stroll.

Walk all the way down Coppersmiths’ Street—jogging right at the end—until you pop out around the corner, on Locksmiths’ Street (Bravadžiluk). Most locals call this lane “Ćevapi Street” for its many ćevabdžinica (shops selling the tasty minced-meat, grilled sausages called ćevapčići). You’ll also see several buregdžinica (shops selling the savory phyllo-dough pastry called burek; my favorite, the recommended Buregdžinica Sač, is just down a side lane off of this street).

Look left, to the yellow-and-brown-striped building at the end of the block. This is one of the city’s main landmarks, the City Hall (Vijećnica)—the best example of Austrian Historicist-style architecture from the 40 years of Habsburg rule. While it looks Islamic, it was designed by a Czech architect who went to Morocco to find inspiration—so it has no connection at all to local culture. Later converted into the City Library, this landmark building—and its books—were destroyed by shells in 1992; today it’s being restored, and is scheduled to open as a museum in 2014. This building is also the place where, on June 28, 1914, that empire’s heir, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, began a fateful drive through town. (We’ll see where that trip ended later on this walk.)

Now turn right and walk a half-block down Locksmiths’ Street, popping out at the bottom of the square where we started this walk. On your right is the Baščaršija Mosque, the first of many we’ll see throughout town (though this one is closed to the public). Kitty-corner from the mosque, notice the copper domes on the roof of the covered market hall (Brusa Bezistan). Dating from 1551, this market hall now holds the City History Museum, with a great model of late 19th-century Sarajevo and other good exhibits (worth visiting for an introduction to the city, and described later under “Sights in Sarajevo”).

• Across from the mosque’s gate, walk down the main street through town.

Sarači Street: Lined with shops, more ćevapi joints, tempting desserts (for some Bosnian treats, see here), and the TI, this busy pedestrian street is a handy artery for sightseeing. Like so many streets in the Baščaršija, this is named for a type of craftsman who worked here—in this case, “Leathermakers.” After a short block, on the left, is the TI. Across the street is the lane called Prote Bakovića, crammed with characteristic (if touristy) eateries. Bakovića also leads to the Old Serbian Orthodox Church, well worth a visit (described later). None of the four Serbian Orthodox Churches in Sarajevo was vandalized during the siege, though they were all damaged by shrapnel launched at nearby targets by the Bosnian Serb Army.

Just beyond the TI, on the right (at #77), dip into the courtyard of the Morića Han, an old Ottoman caravanserai—like an inn, where passing merchants could find food and accommodations. It serves a similar purpose today, with several atmospheric café tables offering the chance to taste the high-octane, unfiltered “Bosnian coffee” (described on here; stop here now if you need to get caffeinated for all the sightseeing coming up).

A few short blocks farther along, on the left, you’ll see the walled courtyard of Sarajevo’s top mosque, the Gazi Husrev-Bey Mosque—definitely worth a visit, and described later. This is just the first of many mentions you’ll see of Gazi Husrev-Bey (1480-1541), a wealthy aristocrat who poured money into the local Muslim community. You can see his tomb next to the mosque (also described later).

Across the street from the mosque’s middle gate (at #33, labeled Muzej Gazi Husrev-Bey) is the Kuršumilja Madrasa, originally built as an Islamic theological school by Husrev-Bey in the 1530s. Step into the outer courtyard for a better look at the building, which has multiple chimneys poking up above the roofline. Students lived in simple “dorms,” each one individually heated by its own stove. You can peek into the inner courtyard, or pay 2 KM to go in and peruse its interesting but dry exhibit about the history of the building (main classroom with a Star of David chandelier—indicating the deep interfaith respect through much of Sarajevo’s history—as well as copies of historical documents and architectural drawings, all described in English; Mon-Fri 9:00-19:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-19:00). The modern school next door (the yellow building, to the right) still teaches the Islamic faith.

Back on Sarači Street, continue past the mosque. After two short blocks, detour a few steps up the street on your right (named—you guessed it—Gazi Husrev-Begova) to see the sparkling-new library that’s associated with the mosque and madrassa, Gazi Husrev-Bey Biblioteka. While local Muslim bigwigs (the modern-day versions of Husrev-Bey) don’t have the money to invest as they’d like in their home country, other Middle Eastern countries (in this case, Qatar) are keeping this tradition of endowment alive. Throughout Bosnia, many destroyed-then-rebuilt mosques and Muslim cultural institutions come with a plaque noting which Islamic country paid to resurrect it. In addition to being a fully operational archive and library (with precious books that were hidden away in a bank vault to survive the siege), this gorgeous new complex includes a large auditorium and a museum that displays its treasures (Mon-Fri 8:00-15:00, www.ghb.ba).

In the opposite direction from the library, you’ll see another covered bazaar, this one still functioning as a market: Gazi Husrev-Bey Bezistan-Bazar. Cut through the market hall—maybe shopping for a scarf, purse, necklace, watch, or sunglasses—and pop out the far end, turning right to find a field (squeezed between the market and Hotel Europe) littered with ruins from a 16th-century Ottoman caravanserai, called Tašlihan. Funded by (surprise, surprise) Gazi Husrev-Bey, this caravanserai hosted passing travelers, traders, and merchants—logically, since it was located next to the bazaar—until it was badly damaged by an 1879 fire.

• Now walk back past the end of the covered market, take the first right, and walk a short block down to the...

Miljacka River: The last building on your left before the riverfront houses the Sarajevo 1878-1918 Museum (described later). The museum outlines the brief but prolific four decades of Austrian Habsburg rule here—and, more importantly, the story of how Gavrilo Princip’s assassination of the Habsburg heir, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, took place right on this corner. The shooting set off a chain reaction of allegiances and grudges that swiftly pulled all of Europe—and, eventually, much of the world—into a Great War that would end the age of empires and inaugurate a new era of modern nations. (For the full story, see “The Shot Heard ’Round the World” on here.)

Go across the street to the Turkish-style Latin Bridge (Latinska Ćuprija)—so named because during Ottoman times, this was an area populated by many Catholics (who said Mass in Latin). After World War I, the bridge was renamed “Principov Most” for the assassin who had asserted Bosnian Serb nationalism against the Habsburgs. But after the 1992-1996 siege, Sarajevans couldn’t stand calling the bridge after a Bosnian Serb, and went back to the old name.

Looking down, you’ll see that the Miljacka is hardly a rushing river (like the Neretva in Mostar)—up here in the Bosnian highlands, this is still just a trickle. While not navigable for trade, the river’s current was harnessed to spur the development of the old Ottoman town. From here, you’re near three sights that may be worth a detour later. Looking across the bridge to the left, you’ll see the minaret of the copper-domed Emperor’s Mosque (Careva Džamija)—the city’s most elegant and oldest, built in 1457 to honor the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror (though it’s been rebuilt and expanded many times since then). Just behind the mosque, a short walk from here, is the Sarajevsko Pivo brewery, a huge facility that churns out every Bosniak’s favorite brew. Because it’s fed by a natural spring, this was one of the few factories that was able to keep working through the siege. It’s also a fine place for a meal in their atmospheric old beer hall (see “Eating in Sarajevo,” later). Those intrigued by Sarajevo’s spiritual history might consider a five-minute detour from here to the Tomb of the Seven Brothers (described later; go straight across the river and up the hill, past the park with the charming little music pavilion/tea house, to the top of the parking lot).

• Backtrack all the way past the covered market to the main drag where we started, turn left, and continue along this strip. This street has now changed its name from Sarači to Ferhadija. Without the slightest transition, you step from the extremely Ottoman-feeling “little Istanbul” of the Baščaršija into the Viennese-feeling Habsburg Quarter.

(See “Sarajevo Self-Guided Walk Old Town Section” map, here.)

With the precipitous decline of the Ottoman Empire in the late 1800s, the Habsburgs—who ruled the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire from Vienna—saw an opportunity to fill the vacuum left in this part of Europe. With the swirl of a pen in 1878, Bosnia went from Ottoman to Austrian rule. As they had throughout their realm, the Habsburgs stepped in and immediately began to modernize Sarajevo, rolling out new infrastructure and buildings like crazy. While they ruled Sarajevo for only 40 years, the Habsburgs left it a far more modern city than they’d found it.

After a few steps on Ferhadija, an alley on the right leads up to the Old Synagogue and Bosnian Jewish Museum (described later)—offering a fascinating look at another of this city’s many faiths.

Just a bit farther, set back from the street on the left, is the small but pretty Ferhadija Mosque. (Just to the right of the mosque, notice the Club Bill Gates. I wonder if they pay him royalties?) If you go around behind the mosque and duck into the Hotel Europe, you’ll find a genteel, chandeliered, Viennese-style coffeehouse interior. The architect who gave Sarajevo its Austrian look—including this hotel—was actually a Czech, Karel Pařík. He lived here for nearly 60 years and designed some 70 buildings in town, including the City Hall, the big Evangelical Church across the river, and the National Museum where this walk ends.

Continuing two more blocks along Ferhadija street, on the right, you can’t miss the Catholic Cathedral (described later). Notice that this is the fourth different house of worship we’ve seen (Muslim, Orthodox Christian, Jewish, Catholic) in just the short distance since we began our walk.

Around the right side of the cathedral is the very sobering Srebrenica Exhibition, documenting the heinous genocidal activities at that eastern Bosnian town. This sight is a must for visitors who want to better understand the atrocities that went on in this country so recently (exhibition described later).

On the opposite (left) side of the cathedral, just before the side door, look for the big Sarajevo rose in the pavement—a distinctive starburst indentation that’s colored in red, and carefully preserved as a memorial, even after the surrounding pavement was replaced. Immediately following the war, about 1,000 of the impact craters in the streets of Sarajevo were filled with a red resin, instantly creating a poignant memorial. As the city has rebuilt, most of these Sarajevo roses have been replaced with new asphalt. Only a few remain, and those are tended to by a local preservation group. I’ll point out a few more Sarajevo roses through the rest of this walk.

Behind the cathedral is an old Ottoman bathhouse (hamam), with telltale copper domes. Today it’s part of a private cultural center called the Bosniak Institute. It sometimes houses special exhibits; if one is going on, you can look around inside.

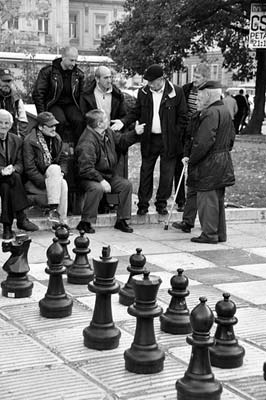

A block farther along Ferhadija, on the left, is a parklike square once called Liberation Square—since renamed Liberation and Izetbegović Square to honor the wartime Bosnian president. The square is ringed with busts of important Bosnian writers, and the Multicultural Man Builds the World statue in the middle—of a naked man doing jumping jacks, with a highly polished member—was donated by an Italian artist to beautify the war-torn city. You’ll see many such examples of donated public art through Sarajevo—quite a few of them are “white elephants” not entirely embraced by the cynical, siege-hardened Sarajevans. At the far end of the square, old-timers gather to play giant-size chess—carefully strategizing while a rogues’ gallery of onlookers cheers and jeers for each move. It’s an enjoyable scene that testifies to the resilience of the Bosnian spirit—and the ability of unemployed locals to find ways to entertain themselves in a miserable economy.

At the end of the square is yet another house of worship: The bold facade and towers of the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral. This was built from 1863 to 1869, during Ottoman rule. In this ecumenical city, the funds came from all quarters: donations from the Romanovs, Russia’s ruling family; from the Ottoman sultan; and from a Serbian prince. Like many houses of worship in this town, the church’s architecture demonstrates the mingling of faiths: It looks like an Orthodox church with a Catholic bell tower. (Bell towers are atypical enough for Orthodox churches, but this one even uses Catholic-style Roman numerals.) While the postwar renovation may not quite be complete, the interior is cavernous and lavishly decorated, with beautifully painted domes and a stirring iconostasis—it’s well worth a look (free, daily 8:00-17:30; for more on the Serbian Orthodox Church, see here).

Continuing along Ferhadija, just after the park on your right is an elegant yellow market hall. Go through (or alongside) this hall and emerge on the other side, then walk to the right one block along the busy street. On the left side of this street, look for Sarajevo’s Markale covered market. Browse your way through humble tables, heavy with produce, to the back corner, where a stone plaque and names engraved on a glass wall recall a pivotal moment in the Siege of Sarajevo. This busy, completely untouristy market gained infamy as the site of two cruel bombings that targeted civilians and claimed more than a hundred innocent lives—Sarajevans who were simply shopping for paltry foodstuffs to keep their families fed and alive through impossibly tough conditions. Sixty-seven Sarajevans died during an attack on February 5, 1994 (plus another 144 wounded), and 43 more died (and 90 wounded) on August 28, 1995. (The blast pattern from one of the bombings, in the floor, is protected by a glass case.) These ruthless bombardments were a turning point in the siege—when the international community began to sit up and pay attention, and realize that this was not simply a standard-issue war between equal parties, but a barbaric siege that was destroying the lives of countless peace-loving civilians who wanted no part of the violence. It was the 1995 attack, in part, that prompted NATO air strikes against Karadžić’s forces two days later. “Operation Deliberate Force” ultimately led to the Dayton Peace Accords, which finally ended the violence—although Sarajevans wish NATO hadn’t been quite so “deliberate” as to wait three and a half years before taking action.

Head back to the main walking street, Ferhadija, and continue on your way. As you walk, in the pavement in front of the Tally Weijl shop (at #12, on the left), look for another Sarajevo rose. The plaque next to the door of the shop explains that on May 27, 1992, 26 Građana Sarajeva (“citizens of Sarajevo”) were killed by an artillery shell while waiting in line to buy bread at a bakery here.

The street angles and takes you up to an intersection with the busy Maršala Tita street, named for the WWII Partisan military hero and president-for-life of communist Yugoslavia—Marshal Tito. On the right at the corner is an eternal flame honoring Partisan fighters. If you’re here in cold weather, you may notice that the practical Sarajevans—who learned during the lean years of the siege never to waste resources—use it to warm up as they pass by.

(See “Sarajevo” map, here.)

Crowded with cars, trucks, trams, and buses, this artery feels more urban and less atmospheric than the Ottoman and Austrian zones we just left. During the siege, this was one of the safest major boulevards in town, since it’s relatively narrow and well-protected from snipers by tall buildings. The exposed side-streets were blocked off to create what was called a “Road of Life,” where people could walk without fear of being picked off by distant gunmen. We’ll follow this street several blocks to ground zero of the former war zone.

After a block, on the right, his-and-hers Atlases flank the doors of the Bosnian Central Bank building—where the fledgling Convertible Mark currency is administered. The all-purpose lights spanning the street here are lit up to celebrate local festivals and (in this multifaith city) a wide range of religious holidays: Ramadan, Catholic Christmas, Orthodox Christmas, and New Year’s.

Farther along, on the left, is McDonald’s, which caused an uproar when it finally opened here in July of 2011. The opening was delayed for four years, as local ćevapi vendors—scandalized by the notion of a multinational conglomerate challenging the loyalty of Bosnian palates—did whatever they could to block it. For weeks after it opened, there were long lines down the street of Sarajevans curious to try the American burgers. But within a few weeks, the furor died down, the crowds dispersed, and the ćevapi sellers were satisfied that Bosnians wouldn’t abandon the grilled meats they’ve enjoyed for centuries.

Two blocks later, the street opens up. On the left is the slick, new BBI Centar shopping mall. On the right is a fine park with one of the most emotionally devastating memorials in this tragedy-laden city: the Memorial to the Children of Sarajevo. Look closely at the symbolism-packed fountain. The glass sculpture in the middle represents a sandcastle, but one that is not—and never will be—finished...the innocent play of a child cut short by an untimely death. The footprints embedded in the concrete basin belong to the young siblings of children who were killed in the war. The silver pillars to the left can be spun to see names of young victims of the fighting. Nearly 1,600 children were among those killed during the siege.

Scattered in the hillsides of the park beyond the fountain, notice a few Ottoman-style gravestones, shaped like turbans—the earliest dating from the early 17th century. In the pavement at the far end of this park—about 30 yards before the crosswalk—look for a Sarajevo rose.

Leaving the park, continue down the busy street. The brown-and-orange building on the left is the Bosnian Presidency (the local “White House”). During the early days of the war, this building was the focus of street-by-street fighting; if the Bosnian Serb forces had claimed it, they could have declared victory. At one point, they were within 50 yards of this building, but the defense held. As part of the compromise to end the war, today Bosnia’s “Presidency” is made up of a committee of three members: one Bosniak, one Croat, and one Serb, with a rotating chairmanship. Difficult as it is to get things done with one president, imagine how impossible the situation is when you need agreement among three people who are predisposed to mistrust each other. While critical for ending the war, this compromise has made it even more difficult to move forward with postwar recovery.

In the park beyond the Presidency is the 16th-century Alipašina Mosque. A long walk directly up the hill from here (with your back to the mosque, about a mile up Alipašina street) would take you to the Zetra Olympics Center (not worth a detour now, but worth considering if you’re curious and have time later). This complex includes Koševo Stadium, which held the opening ceremony for the 1984 Olympics (and, in 1997, hosted visits by both Pope John Paul II and the band U2—both of whom had spoken out in support of the besieged Sarajevans), and Zetra Arena, which was used for Olympic skating events (this is where Torvill and Dean thrilled the world with their ice dancing) and for the closing ceremony. Today the complex houses a museum about those games. Poignantly, the stadium that once commanded the world’s attention is now surrounded by a vast field of headstones—mostly of Sarajevans killed during the war. The ice arena’s basement was used as a makeshift morgue, and its wooden seats were used to build coffins for the deceased.

• Our walk is finished. From here, you can circle back to any of the sights you haven’t yet seen. If you have stamina and interest left, you can continue directly on to the next walk, which covers the main sights of the Siege of Sarajevo. It begins just a 10-minute walk away: Simply continue following Maršala Tita street, jogging left with the road and passing another park (with a conspicuously modern sculpture that was another artist’s “white elephant” gift to Sarajevo). Soon after, you’ll reach the major intersection where Maršala Tita street passes a big church and becomes the city’s main thoroughfare (Zmaja od Bosne)—and where the next walk begins.

(See “Sarajevo” map, here.)

This walk, which leads you through the broad boulevards and skyscraper jungle of modern Sarajevo, is designed to help you appreciate some of the key sites of the Siege of Sarajevo, and to provide an interesting way to get to the worthwhile Historical Museum (which further illustrates the way people lived during the siege) and the National Museum (though this is likely closed, due to lack of funding). The walk begins in the shadow of the Bosnian Parliament building, which you can reach by walking 10 minutes from the end of the self-guided walk (above) or by riding a tram to the Marjin Dvor tram stop. This neighborhood is officially called Marijin Dvor (roughly “Maria’s Castle,” after a nearby palace that was built for an aristocrat’s wife)—a strangely romantic name for a modern “downtown” turned war zone. These days it’s better known as “Sniper Alley,” the nickname given it by foreign journalists who covered the besieged city.

• Begin your visit to this part of Sarajevo with a...

“Sniper Alley” Spin-Tour: Stand near the engraved medieval tomb at the corner of the big intersection in front of the Bosnian Parliament (the tall, glassy building). Look up to the hillside across the river. High on that hill, the patch of land with the grave markers is the city’s main Jewish cemetery; during the siege, Karadžić’s snipers found this an ideal position from which to rain bullets down on the innocent civilians below. People would cross this street only at night, by cover of darkness, or occasionally by running behind a moving UN armored vehicle that provided cover. Just two decades ago, if you stood here long enough to read this paragraph, you’d be dead.

Spin to the right to see the towering, glassy skyscraper—the Bosnian Parliament building. While freshly rebuilt today, this was utterly destroyed during the war.

Looking farther to the right, up the big boulevard, you’ll see the prominent, bright-yellow facade of the Holiday Inn. When it was built for the 1984 Olympics, this was the premier hotel in Sarajevo, fit for visiting dignitaries. But less than a decade later, the first shots of the Bosnian War were fired right here. As tensions were rising throughout Bosnia-Herzegovina, tens of thousands of peace protesters filled this street on April 5, 1992. Karadžić instructed snipers positioned in the hotel to open fire on the unarmed crowd, killing six and wounding many others. Later, the hotel housed foreign journalists and dignitaries, and was therefore virtually the only safe space in the entire city center—though even this enclave suffered its share of incidental damage. Since the war, the hotel has been fully renovated.

Turning to the right, you see the Catholic Church of St. Joseph (built by the Czech architect Karel Pařík). The street to the left of the church, with a clear view from the sniper’s nest in the Jewish cemetery, is called Tršćanska (“Trieste Street”)—but locals began calling it Trćanska, “Running Street,” where it was deadly to walk at a normal pace. Behind the church stands a hospital. While the side of the hospital facing away from the hillside sniper’s nest was a safe place for injured and ill Sarajevans to recover, the side facing the hill was exposed to sniper fire...a lesson learned in the worst possible way when snipers shot through the windows of the hospital to kill patients lying in their beds.

• From here, if you want to go straight to the Historical Museum, continue up the main street past the Bosnian Parliament, then carry on two long blocks to reach the museum (on your left). But for a more interesting approach—dotted with significant siege locations—take the scenic back way along the river. With your back to the church, walk five minutes down the street to the river and the...

“Romeo and Juliet Bridge”: This bridge was originally named “Vrbanja Bridge,” but now it’s officially called “Suada Dilberović and Olga Sučić Bridge” for the two young women who were the first documented victims of the Siege of Sarajevo. Dilberović was a Dubrovnik-born Bosniak pursing her medical degree at the University of Sarajevo, and Sučić was a Croat resident of Sarajevo; both were killed by sniper bullets while standing on this bridge during the Holiday Inn peace rally massacre. But this bridge is internationally better known as “Romeo and Juliet Bridge,” for two other victims of the war. Two young Sarajevans—Admira Ismić (a Bosniak) and Boško Brkić (a Serb)—were lovers who wanted to escape to a better life together. Brkić used his connections with Serb officials to obtain promise of safe passage out of the city. On May 19, 1993, the couple made it as far as this bridge before snipers opened fire; both were hit and fell to the ground. Boško died instantly; Admira crawled to her beloved, and died clutching his body in her arms. The bodies could not be retrieved and buried for fear of further sniper attacks, so they lay on the bridge for another week, locked in a heart-wrenching embrace. After four days, American war correspondent Kurt Schork issued a dispatch describing the corpses, grabbing the attention of people around the world with this example of the horrifying conditions in the Bosnian capital. The ill-fated “Romeo and Juliet of Sarajevo” have been immortalized in film, song, and news accounts. Sarajevans embrace the couple for the way they embody a united Sarajevo—with people of various ethnicities living together under siege. As Ismić’s father said in Schork’s dispatch, “Love took them to their deaths. That’s proof this is not a war between Serbs and Muslims. It’s a war between crazy people, between monsters.”

Directly across this bridge is the Grbavica neighborhood, the closest Bosnian Serb forces got to the city center during the siege—which is why the area we just passed through was so deadly. The snipers were just a couple of blocks away.

• Turn right and stroll along the river for a couple of blocks, along the...

Woodrow Wilson Promenade (Vilsonovo Šetalište): Though this was a deadly no-man’s-land just two decades ago, today it’s a pleasant, tree-lined riverside park. But here in Sarajevo, even a pretty park has a sinister edge: The trees here survived only because they were too close to enemy lines to safely cut down for fuel.

Stow your guidebook and enjoy this romantic walk for a while. Soon you reach the Ars Aevi Bridge, designed by Paris’ Pompidou Centre architect Renzo Piano, who has also drawn up plans for the nearby future home of Sarajevo’s contemporary art museum.

At this bridge, turn right and head away from the river. You’ll pass through a field that’s the future site for the Ars Aevi contemporary art museum (www.arsaevi.ba). Just beyond that, tucked into the back wall of the Historical Museum, are the outdoor tables of the Tito Café. This kitschy hangout celebrates the dictator of communist Yugoslavia with preachy red flags, lots of old photos, camouflage stools, and a bust of the beloved leader, as well as an old jeep and other Yugoslav military vehicles scattered out front. (The tank you’ll see out front is a WWII-era relic, which was actually put into use again during the siege.) The clientele seems split between those who really do miss Tito, and those who are here ironically...but either way, they’re having fun. (While nursing a drink here, read the “Tito” sidebar on here.)

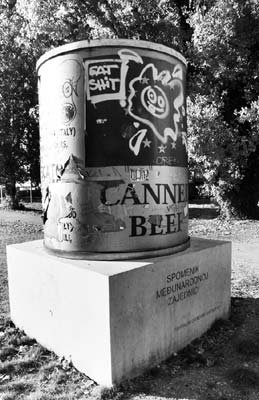

When finished at the café, walk straight back toward the bridge, then turn left on the paved sidewalk through the park. On your right, look for the monument shaped like a giant tin can with an ICAR label. This is a (somewhat ironic) thank-you for international relief supplies sent to Sarajevo during the siege, including the canned meat that sometimes appeared in care packages from the European Community. Understandably, Sarajevans have a love-hate nostalgia for this “siege Spam.”

After the big can, turn left, heading toward the big street. On the left, look for another ironic monument, a big stone slab, on the left (next to the stairs to the Historical Museum). This reads, “Under this stone there is a monument to the victims of the war and cold war.”

The stairs next to this slab lead up to the gloomy concrete home of the Historical Museum, with a quirky but fascinating collection of everyday items used by Sarajevans to survive the siege (described later).

Exiting the Historical Museum, you’re facing the genteel mansion housing the National Museum—which, as of this writing, was closed due to lack of funds...but you can try going in the main door (middle of building, facing busy road) just in case.

Across the street from the National Museum, you can see the sleek, low-slung US Embassy building, which fills a huge walled complex in the heart of downtown—keeping a cautious eye on a city that has seen more than its share of turmoil over the past generation or two.

• Our tour of “Sniper Alley” is finished. From here, you can visit the Historical Museum; walk or ride a tram (#2, #3, or #5) back to your starting point in the Old Town; or, for one more poignant siege sight, take a taxi or tram #3 (plus a short taxi ride) out to the War Tunnel Museum (described later).

▲City History Museum (in Brusa Bezistan Covered Market)

▲▲Gazi Husrev-Bey Mosque (Gazi Husrev-Begov Džamija)

▲▲Sarajevo 1878-1918 Museum and Archduke Franz Ferdinand Assassination Site

Near the Old Town (Baščaršija)

Cemeteries and Viewpoint just Above the Baščaršija

▲▲Old Synagogue (Stari Hram) and Bosnian Jewish Museum (Muzej Jevreja BiH)

▲▲Srebrenica Exhibition (Memorijalna Galerija 11/07/95)

▲Historical Museum of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Historijski Muzej BiH)

▲▲Sarajevo War Tunnel Museum (Sarajevski Ratni Tunel)

I’ve organized Sarajevo’s main sights as you’ll reach them while you follow my self-guided walk, above.

Filling a big indoor silk bazaar right on old Sarajevo’s main square, this good museum features a giant model of the city in 1878, at the apex of the Ottoman period and just before the new Austrian rulers renovated and expanded Sarajevo. The rest of the collection offers a fine historical overview of the city in English, with actual artifacts, traditional costumes, and a good video tracing Sarajevo’s story (with English subtitles). Particularly with the closure of the National Museum, this is the best place in town for a look at local history.

Cost and Hours: 3 KM, 5-KM guidebooklet, Mon-Fri 10:00-16:00—until 18:00 mid-April-mid-Oct, Sat 10:00-15:00, closed Sun, Abadžiluk 10, tel. 033/239-590, www.muzejsarajeva.ba.

Visiting the Museum: As you enter, you’ll first circle clockwise around the ground floor for a quick look at prehistoric, Roman, and medieval Sarajevo. Near the end of this section (back near the entrance), notice the two big Bogomil tombstones (from the medieval Bosnian Christian civilization)—an older, horizontal one and a later, vertical one. The vertical tomb is a transitional piece that demonstrates how Bogomil culture began to take on Turkish customs after the arrival of the Ottomans. The tomb has been rotated upright (in keeping with the Muslim tradition) and displays a Muslim-style crescent moon. A man with a bow and arrow is a common motif on Bogomil tombstones. Here, we see the bow and arrow, but not the man (in keeping with the Muslim ban on depicting living things in art). But, in a sort of compromise, it does feature an animal. Nearby is an unusual wooden sarcophagus, which may have held the remains of an important person.

Upstairs, do another clockwise loop, beginning with the origins of the city of Sarajevo. One display case demonstrates the religious diversity of this city—from an Orthodox Easter egg, to a Torah and menorah, to a copy of the Old Testament. The traditional clothing exhibit shows how local styles were influenced by Venetian, Slavic, and Turkish trends, while the one on crafts and trade features items you may have found for sale in the bazaars. Under Ottoman rule, the city saw a flourishing of the arts (see the calligraphy) and education, but as that empire began to decline, illiteracy skyrocketed and Bosnia’s neighbors sensed weakness (exemplified by the case full of weapons). Ultimately Bosnia became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (see the new flag of Sarajevo up above), which changed local lifestyles and fashions. Notice the paintings of Bosnian Muslims of this era, who wore Austrian-style suits, but with fezzes and turbans. The remaining exhibits show architecture from the Habsburg period, when the very Turkish-style Old Town was surrounded by a Viennese urban zone.

While fully Orthodox inside and out, this 16th-century church has features that resemble a synagogue or a mosque—hinting at the mingling of faiths that has characterized Sarajevo for most of its history. Stepping inside, notice that the church (which was built on the site of an even earlier one) is set about three feet below street level. Because the Ottomans wouldn’t allow churches to be taller than mosques, the builders went down instead of up. Also notice how—with its split-level design and upstairs gallery—it feels like a synagogue with an iconostasis. Upstairs in the gallery (another feature more commonly seen in synagogues and mosques than in churches), you may see worshippers making a fuss over a small coffin, which contains the body of a child; this is believed to have healing power, especially for infertile women. Across the small courtyard is a museum with old icons, incense burners, vestments, and manuscripts in Cyrillic. Look for the document in squiggly Arabic script—a written confirmation from the Ottoman sultan permitting worshippers to practice the Orthodox Christian faith here. The wine shop keeps up the Bosnian tradition of Orthodox monks doubling as vintners.

Cost and Hours: 2 KM, includes church and museum, Mon-Sat 8:00-18:00, Sun 8:00-16:00, Mula Mustafe Bašeskije 59.

Called “Begova Mosque” for short, this is Sarajevo’s most important and most historic mosque. For more on Bosnia’s Muslim faith, see here.

Cost and Hours: Outer courtyard-free; mosque-2 KM—buy ticket at little house to the left as you enter courtyard; specific opening times vary depending on prayer schedule and are posted at ticket office—generally May-Sept daily 9:00-12:00 & 14:30-16:00 & 17:30-19:00, Oct-April open sporadically, closed to visitors during Ramadan, Sarači, tel. 033/532-144, www.vakuf-gazi.ba.

Visiting the Mosque: Start in the outer courtyard. The fountain in the middle (with water piped in from the mountains three miles away) is for washing before prayer. Around the left side, look for the two freestanding mausoleums (you can’t enter them, but you can peek through the windows around the side). The larger one holds the remains of the mosque’s founder and namesake, Gazi Husrev-Bey (1480-1541; bey is an Ottoman aristocratic title, like “Lord” or “Sir”). He was a governor of Bosnia who donated vast sums to improving Sarajevo (throughout the Old Town, look for plaques that say Gazi Husrev-Begov-Vakuf—marking his gifts to the city). The smaller mausoleum holds his assistant and secretary, a highly educated Croat named Tardić who had been captured in a battle. He accepted Gazi Husrev-Bey’s offer of a job, a precondition of which was that he convert to Islam, and went on to become the governor’s most trusted advisor. The cemetery behind the mausoleums has graves both old and new; one of the most recent holds the remains of the imam from the destroyed mosque in Banja Luka, a Serb stronghold in northern Bosnia.

Now, let’s go inside. Buy a ticket at the office and step into the mosque’s interior (women must cover their heads, but visitors can keep their shoes on). You’ll see many of the same elements found in other Bosnian mosques (see description on here). Appreciate the remarkably spacious-feeling architecture. Many of the carpets are gifts from Muslim nations and date from the Tito era. As an anchor of the non-aligned world, which included many Muslim countries (in North Africa and the Middle East), Tito had particularly good relations with Islamic leaders. The electric lighting—the world’s first in a mosque—was installed by the Habsburg rulers in 1898 (the same year they lit up Vienna’s Schönbrunn Palace), suggesting how deeply the Habsburgs respected the local Islamic faith. The besieging Bosnian Serb forces in the 1990s didn’t share this respect, and used the mosque’s minaret for target practice. Looking through the windows, you can see the walls are six feet thick—which helped save it from utter destruction. The mosque was badly damaged, and renovated in 1996 using funds largely from Saudi Arabia; the interior—while covered in fine calligraphy—is still less ornately decorated than it once was.

Nearby: The clock tower across the narrow street is also part of the mosque complex; notice that its “noon” lines up with sunset—critical in establishing the five times each day that Muslims pray. Under the clock tower you’ll find a free public WC and a little hole-in-the-wall bakery that’s open late.

Worth ▲▲▲ and ample goose bumps to historians with vivid imaginations, and interesting to anyone, this is the nondescript street corner where the heir to the vast but declining Austro-Hungarian Empire met a bloody fate at the hands of a Bosnian Serb separatist, plunging Europe into the War to End All Wars (until the next war). The shots were fired as Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie sat, JFK-and-Jackie style, in an open-top car during a visit to the Bosnian capital (for the full story, see the sidebar). The street corner where it happened, across from the Latin Bridge (Latinska Ćuprija), is now home to a plaque and a humble one-room museum, which shows a good video montage in its window that helps illustrate the story. The Sarajevo 1878-1918 Museum traces the four decades when this city was part of the Vienna-ruled Austro-Hungarian Empire, with a special emphasis on the assassination. Just inside the entrance, look for the symbolic footprints of the assassin, Gavrilo Princip. Beyond that, the museum holds one well-presented room featuring the trappings of the age, a map showing the sites relating to the assassination, life-size mannequins of Franz Ferdinand and Sophie, and clips from a 1970s-vintage Yugoslav film about the assassination, all with English labels.

Cost and Hours: 3 KM, Mon-Fri 10:00-18:00, Sat 10:00-15:00, closed Sun, Zelenih Beretki 1, tel. 033/533-288, www.muzejsarajeva.ba.

The nondescript mosque at the top of the parking lot across the Latin Bridge from the Old Town is a favorite spot for Sarajevo superstition. Along the right, outer wall of the mosque are a door and seven windows marking tombs of (according to legend) innocent people who were unjustly sentenced to death; a strange light was reported to be emanating from their graves at night. It’s believed that if you put a coin of the same value in each of these eight slots, you can make a wish or a request. Then you are supposed to walk around the top of the mosque, turn left, and walk down the little lane. Listen carefully—the first words you hear as you walk along this street will help you divine the answer you seek. Interestingly—but not surprisingly for this fundamentally ecumenical town—even non-Muslim Sarajevans come here when they are searching for enlightenment.

If you walk about 10 minutes up Kovači street from the Sebilj fountain, you’ll come to a fine viewpoint over the Old Town, as well as some large, thought-provoking cemeteries from the siege years. Looking even higher in the hills, you’ll see more sprawling cemeteries blanketing the hillsides. People were buried in these places either at night or in heavy fog, when gravediggers could be safe from snipers.

At the top of Kovači street, the Kovači Martyrs’ Memorial Cemetery is worth a pensive wander. The billboard near the entrance labels each grave. High on the hill is the ceremonial metallic-domed grave of wartime president Alija Izetbegović, surrounded by a crescent-shaped fountain that feeds a stream that trickles downhill between the other headstones. (Just uphill, inside an old tower from the city wall, is a small museum dedicated to Izetbegović.)

Just above this area is a neighborhood called Vratnik (roughly “Gateway”), the oldest part of town.

If you’d like to tour a traditional home from the Ottoman period, hike five minutes uphill from the Old Town to see this well-preserved, sprawling estate, built in the 17th century by a wealthy local Bosniak family. It’s similar to the “Turkish houses” you’ll see in Mostar—except that it’s made of wood, as is typical of Bosnia, while Herzegovinian homes (like those in Mostar) are made of stone. First, you’ll head upstairs to see the men’s sitting room (halvat), the women’s room (where the ladies of the house did their embroidery), and the dining room (where guests sat on the floor around the low table, or up on the long divans all around the room). The kamarija (balcony) overlooks the inner courtyard, with its garden and well. Then head downstairs to see the big kitchen and large halvat—for big family gatherings.

Cost and Hours: 3 KM, 5-KM guidebook, Mon-Fri 10:00-18:00—or until 16:00 off-season, Sat 10:00-15:00, closed Sun, Glođina 8, tel. 033/535-264, www.muzejsarajeva.ba.

Immediately west of the Ottoman quarter is the more modern part of town, built at the end of the 19th century after Bosnia became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. While several of the sights scattered through this area are much older, most of the buildings here are evocative of those in the capital at the time, Vienna.

Combining a classic old 16th-century synagogue with an excellent and insightful museum chronicling the Jewish faith in this country, this building was modeled after a synagogue in Toledo, Spain. Soon after the Jews were expelled from that kingdom in the late 15th century, Sephardic Jews made their way to Bosnia, which they found to be an unusually tolerant place (typical of its entire history). Unlike many Central and Eastern European cities, Sarajevo did not relegate its Jews to a ghetto; they lived amid their non-Jewish neighbors. Local Sephardi used “Ladino,” a unique language mixing Spanish and Hebrew (even today, rabbis greet each other not with Shalom, but with Buenos días).

Cost and Hours: 3 KM, 5-KM guidebook, Mon-Fri 10:00-18:00—or until 16:00 mid-Oct-mid-April, Sun 10:00-15:00, closed Sat, Josipa Štadlera 32, tel. 033/475-740, www.muzejsarajeva.ba.

Visiting the Synagogue and Museum: Buy your ticket and step into the central hall, with the bima (altar-like raised area) in the center and the wooden doors that hold the Torah. Women, who in accordance with Jewish tradition worship separately from men, stand up in the arcades ringing the hall. Climb up the stairs to see the exhibits filling those arcades. On the first floor up, you’ll see a replica of the important Sarajevo Haggadah book (see sidebar, next page); a tombstone from a Jewish cemetery on the hill across the river, which is the second biggest in Europe (after Prague’s) and was tragically used as a sniper’s nest during the siege; and a model of the original appearance of this synagogue. The next floor shows more Jewish religious items and illustrates how local Jews adopted local culture (for example, you’ll see Jews wearing Muslim-style fezzes). The replica of an Ottoman-era “pharmacy” with herbal cures is a reminder that such businesses were typically run by Jewish Sarajevans.

The top floor focuses on the dark 20th century, including the Holocaust. The exhibit profiles Bosnians who were designated as “Righteous Among the Nations”—an honorific for non-Jews who risk their own lives to save their Jewish neighbors. Among these is Derviš Korkut, the Muslim museum curator who saved the Sarajevo Haggadah from Nazi investigators. Some Jewish women were smuggled out of Nazi-occupied areas by disguising themselves in Muslim veils. You’ll also see Nazi-mandated armbands identifying Jews, photos of resistance fighters, and an exhibit on the reprehensible Jasenovac concentration camp on today’s Bosnian-Croatian border—where Jews, Serbs, Roma (Gypsies), antifascist Muslims and Croats, communists, and other enemies of the Ustaše-controlled state were savagely executed. Jasenovac lacked the “high-tech” gas chambers of other Nazi camps, so they resorted to more medieval methods, murdering their victims by knife, sword, or even a hammer to the skull. And yet, even through that dark history, Sarajevo has remained a place where cultures coexist side-by-side: Position yourself so that you can look through the Star of David window to see a minaret.

Dating from 1884-1889, this Historicist structure mingles different “Neo-” architectural styles (typical of Viennese buildings of that age): a Neo-Gothic exterior and a Neo-Byzantine/Neo-Baroque interior. Notice the big gap across the street, offering a fine view of the adjacent hillside. During the siege, the church’s front door was dangerously exposed—not only to snipers, but to anti-aircraft machine guns, which were used to periodically spray bullets randomly over the town. Inside, the red-and-white-striped ribs—a Neo-Moorish style element—is rare in a Catholic church, but seems to fit here in ecumenical Sarajevo. Inside and on the left, look for the grave of the church’s Croatian founder, Joseph Stadler, and a plaque commemorating Pope John Paul II’s trip here on April 12, 1997—Bosnia’s first-ever papal visit.

Cost and Hours: Free, 2-KM guidebooklet, no shorts, daily 9:00-16:00, Trg Fra Grge Martića 2.

Worth ▲▲▲ for anyone who wants to better understand the atrocities in Bosnia’s recent history, this important, emotionally exhausting exhibition uses photographs and video clips to tell the story of the remote Bosnian village that experienced the worst massacre on European soil since World War II. It’s well worth the extra 2 KM to tour the exhibition with a guide (departing regularly—ask when the next tour begins, and pass any waiting time watching the powerful videos).

Cost and Hours: 10 KM, or 12 KM with a tour, daily June-Sept 9:00-22:00, May and Oct 10:00-20:00, Nov-April 10:00-18:00, Trg Fra Grge Matića 2/III, tel. 033/953-170, www.galerija110795.ba.

Visiting the Exhibition: Because of the horrifying massacre that took place there (described in the sidebar on here), the name “Srebrenica” has become synonymous with some of the worst crimes against humanity in recent memory. The date you’ll see everywhere—11/07/95—commemorates July 11, 1995, when Bosnian Serb forces invaded Srebrenica, beginning their genocidal attack. This exhibit, consisting mostly of haunting photographs by Tarik Samarah, documents the process of piecing together exactly what happened there. Photos show the faces of just 640 of the more than 8,000 victims; conditions in the refugee camps where survivors lived after the massacre; the process of exhuming, documenting, and investigating the many mass graves that have been discovered (mass funerals are held on July 11 each year to honor victims who were identified during that year); and some graphic and unsettling graffiti by UN troops from the Netherlands, which suggests that they felt more contempt than sympathy for the people they were assigned to protect.

Perhaps the most powerful part of the exhibit is the gripping, wrenching 27-minute video loop, which outlines (with English subtitles) the harrowing chain of events that led to the fall of Srebrenica and the ruthless murders of so many of its residents. Maps on the wall nearby identify the locations of mass graves that have been found so far. Out in the hallway, a 50-foot-long wall lists the name and date of birth of each of the 8,372 victims who have been identified so far; the alphabetical list makes it clear that entire extended families were wiped out. Nearby, touchscreens with headphones let you view individual testimonials from survivors and victims’ relatives (subtitled in English). For even more information, sit at one of the terminals in the first room, where you can click through more than four hours of video documentation. The quote on the wall reminds visitors of a lesson that, it seems, needs to be repeated again and again: “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.”

For the most interesting approach to this area from the Old Town (Baščaršija), see my self-guided walk, earlier.

Filling a still-bombed-out-feeling, Tito-era building next to the National Museum, this museum features a very small and ramshackle but fascinating exhibit explaining the Siege of Sarajevo—if you take the time to examine and appreciate the items and photos. While there are some English labels, they’re sparse, and it helps to have a Sarajevan explain the items firsthand; this is a good place to come with a local guide.

Cost and Hours: 5 KM, dry 10-KM book, Mon-Fri 9:00-19:00, Sat-Sun 9:00-14:00, Zmaja od Bosne 5, tel. 033/226-098, www.muzej.ba.

Visiting the Museum: Formerly the “Museum of the Revolution,” the building’s stairwell still features Socialist Realist mosaics from the communist period, and a statue of Tito stands in the inner courtyard. Head upstairs to see the exhibit. Note that the collection is in flux, and they’re hoping to secure funding that would help them install a more modern exhibit.

In the middle of the main hall, you’ll likely find an exhibit about the war crimes tribunal in The Hague, with good English explanations and an engaging film that illuminates the process. All around is the “Sarajevo Surrounded” exhibit, with lots of artifacts from siege-time Sarajevo. Follow the chronological exhibit, which uses photographs, news clippings, and other items to tell the story of the siege. Most illuminating are the many actual items that show how Sarajevans improvised ways to carry on during the three and a half years under siege. For example, look for photos of the “Sarafix” technique—invented here, out of necessity—which allowed doctors to set a broken bone with a metal frame with pins instead of a traditional cast. The display of cigarettes explains how smokes were used as a sort of currency; even through the siege, the local cigarette factory kept working, though the product sometimes had to be packaged in makeshift wrappers.

The mockup of a typical siege-time apartment shows how people were forced to make do. The windows and roof are covered with a plastic tarp donated by the international community. The TV, telephone, refrigerator, and other appliances were useless without electricity. (The power might come on sporadically, but never for very long.) Look around at the so-called “Sarajevo inventions,” created by desperate and clever people to keep going. Notice the makeshift stove (a collection of several other, smaller stoves is nearby). During the frigid Sarajevo winters, trees were cut down to fuel fires. When the trees were gone, firewood was in short supply (a bundle might cost the equivalent of $50), so besieged residents burned their furniture, shoes, old toys—anything flammable. And they bundled up in as many clothes as possible. After 1994, natural gas was available in some areas; notice the recycled IV tube (still bloody inside) used to power the gas lamp.

The market stall displays the paltry essentials that Sarajevans considered themselves lucky to find during wartime. Imagine picking over these meager offerings—rusty canned goods, military rations, plastic bags stuffed with grains—and trying to figure out how to use them to feed your family. Notice the Monopoly-like money that was the city’s ersatz legal tender during the siege. Sarajevans learned how to stretch a “one-day ration” for up to two weeks. (Many nations sent old military rations—Sarajevans might find themselves eating leftover US rations from the Vietnam War.) Lawns were converted into makeshift produce gardens. Everyone came up with “siege recipes,” replacing unavailable ingredients with whatever they could. For example, during a time when rice was relatively plentiful, they’d mix it with flour to make bread, or use it as filling for bureks (savory pastries). Instead of spinach filling for a burek, they might use greens from buttercup flowers. And when they had a taste for coffee, they’d burn rice, grind it, and mix it with hot water; they swear the taste was similar...even if it was missing the caffeine kick.

A few more things to look for: The actual shells and weapons were used in the fighting. The elaborate satellite telephone was, for a time, the only way that Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović could communicate with the outside world. One case shows ways that people created light, including a candle made of pork fat with a wick made from carpet fibers. Viewing these items, the desperate ingenuity of the besieged Sarajevans is positively inspiring.

This humble museum, which has for years struggled to do justice to the illustrious history of this fascinating nation, closed indefinitely in 2012 due to budget cuts. If it happens to be open during your visit (check the latest at www.zemaljskimuzej.ba), it’s worth a visit for the chance to peek (through a glass door) at one of the world’s most priceless books, the Sarajevo Haggadah (see sidebar on here). The rest of the museum features exhibits on archaeology and ethnology—like an open-air Bosnian folk museum moved inside.

In the countryside on the southwestern outskirts of Sarajevo, near the airport, is a small but fascinating museum celebrating the ingenuity and determination of the besieged Sarajevans to continue supplying their city. Here you can walk through a small stretch of the actual half-mile supply tunnel they dug to stay alive during the siege. The still battle-scarred house that marks its entrance holds a small museum, displaying actual items used in the tunnel.

Cost and Hours: 10 KM, daily April-Oct 9:00-17:00, Nov-March 9:30-16:00, last entry 30 minutes before closing, Tuneli 1, mobile 061-213-760, tel. 033/778-670, info line tel. 033/778-672, www.tunelspasa.ba, info@tunelspasa.ba. Your ticket includes a free tour (usually lasting about 30 minutes), but only if you call a few days ahead to arrange a time.

Getting There: The tunnel is a long detour from anyplace else in town. Therefore, the most convenient option is to take a guided tour that includes transportation from downtown and a clear explanation of what happened here. Various companies offer these tours, including Insider Tours (see “Tours in Sarajevo,” earlier). By taxi, the fair metered rate from downtown is 15-20 KM one-way—just tell them “tunel.” Alternatively, you can take tram #3 or bus #32 from the Old Town to the end of the line (Ilidža stop, about 40 minutes one-way), then walk 2.5 miles or pay 5-10 KM one-way for a taxi from there. If you’re flying into or out of the city, this combines well with your trip to the airport.

Background: With the city almost entirely surrounded by the Bosnian Serb Army, the Sarajevans’ lone connection to the outside world was a mountain pass. But between them and that pass was the city’s airport—which couldn’t be crossed by either side because it was controlled by the impartial UN. Sarajevans could only gaze across the runway at the mountains that could be their lifeline. So, rather than go through the airport, they went beneath it—digging a half-mile-long tunnel under the runway. Coal-mine engineers spent four months and four days in 1993 digging a passageway that was about five feet tall and three feet wide. Once completed, Sarajevans could enter the basement of an apartment building, hunch over and hike through thickly humid air for 20 minutes, and emerge at a house on the other end. (After a heavy rain, the tunnel would fill with water, making the hike even more unpleasant.) From the house, they could hike over the mountains to get supplies. While money was scarce, cigarettes produced at Sarajevo’s factory could be traded for what was needed, which was carried back over the mountains and through the tunnel. Eventually the tunnel was wired to also supply electricity and natural gas into the city, and was equipped with rails to more efficiently transport goods on wheeled carts. The tunnel was open to any Sarajevan—and people used it to shuttle back and forth, day and night—but it was carefully monitored for smugglers who might use it to profit from the tragedy inside the city. While the besieging enemy knew about the tunnel, its nonlinear course underground made it impossible for them to know exactly where it was—and even if they had known, to destroy it they’d have had to go through the UN-controlled airport. The best they could do was to relentlessly bombard the tunnel’s entrances.

Visiting the Museum and Tunnel: After buying your ticket, you’ll walk through the small three-room museum, then see the tunnel itself, and have the chance to watch a movie about this site’s history.

The museum’s first room displays military equipment, including shell casings (this area was bombarded with more than 300 grenades daily, with 3,777 being launched here in one day alone), and photos and orders relating to the tunnel’s construction.

The second room displays the chair on wheels used to push the ailing President Izetbegović through the tunnel—hardly presidential transport, but the only way he could safely get in and out of the city for diplomatic meetings.

The third room displays various items representing the challenge of simply staying alive in Sarajevo while it was under siege. Notice the small display of paltry foodstuffs. The canisters—including a tin box with a spigot—demonstrate the struggle to find drinking water. In the frame you’ll see the contents of an aid package that was expected to last one person for 10 to 15 days. Lighting was often as simple as oil and water in a glass jar with a wick. The broken glass window over the stove illustrates the absurdity of trying to keep warm through a frigid winter when basic insulation was an impossibility. Between the doors, notice the two uniforms that show how the initially improvised Bosnian defense forces evolved as the war went on: At first, they wore jeans and tennis shoes, while later they had real uniforms and boots. Also look for the photos of the many celebrities who have visited this place.

Along the back wall, you can see the various types of carts used to transport food, weapons, and sick people through the tunnel. It was used both by the military (the cart with artillery boxes), and by civilians (the dolly with backpacks and boxes). The makeshift canvas boots—roughly stitched together using material donated by the international community—were pulled on over regular shoes to trudge through the water that collected on the tunnel floor. Notice the cables and pipes along the back wall—a reminder that the tunnel was used not only for people and supplies, but also for electricity and gas.

Then follow the marked route to the tunnel itself (passing an artillery shell still embedded in the cement floor), where you can climb down the tight stairs and squeeze through an actual 80-foot-long stretch. Imagine yourself walking, crouched over, 30 times this far from one end to the other. If you’d like, you can hike through the tunnel wearing a backpack loaded with 65 pounds—roughly the amount that women typically carried through the tunnel (men would carry more than double that much).

Near the tunnel entrance (and in the open-air sheds out back), you can watch a good 20-minute film that illustrates the construction and use of the tunnel.

Out back are several places to sit and look at a map of the besieged city—superimposed, not without irony, over a map from the 1984 Olympic Games. The actual airport sits on the horizon. (Locals say that when they saw a UN plane taking off—likely carrying international officials to safety—they knew trouble was brewing.) In 1993, for the first time, Bosnia-Herzegovina selected a band to represent the newly independent country at the Eurovision Song Contest (a Europe-wide TV extravaganza somewhat like the finale to American Idol). The band, Fazla, was trapped in Sarajevo by the siege. Determined to make it to the show in Ireland, they ran across the UN-controlled airport runway with their instruments, which they then carried over the mountains to freedom. By the time the band returned, the siege tunnel under the airport was finished, and they were able to easily sneak back into the city. Even many people who managed to leave the city chose to return and remain under siege with their families and neighbors, rather than abandon their unique city and way of life.

This vertical city’s gorgeous setting is best seen from high up. Unfortunately, most viewpoints are not easily reachable by public transportation. One option is to walk from the Old Town up Kovači street for a decent (if not sky-high) view over town (see here). Or you can take a taxi up to the popular viewpoint called White Bastion (Bijela Tabija), at an old fortress (a taxi from the Old Town should cost you about 10 KM round-trip). Bus tours around Sarajevo include at least one panoramic viewpoint that offers grand vistas over one of Europe’s most spectacularly set cities.

The city enjoys a wide variety of good accommodations, ranging from budget hostels to cozy and warmly run little pensions to plush hotels. All of my listings are in or very near the Old Town (Baščaršija) and the start of my self-guided walk. Places that are actually in the Baščaršija come with some nighttime noise.