Chapter 29. Investigating Protista

Equipment and Materials

You’ll need the following items to complete this lab session. (The standard kit for this book, available from www.thehomescientist.com, includes the items listed in the first group.)

Materials from Kit

Goggles

Coverslips

Magnifier

Methylcellulose

Pipettes

Slides, flat

Slide, deep well

Stain: eosin Y

Stain: Gram’s iodine

Stain: methylene blue

Materials You Provide

Gloves

Microscope

Slides, prepared (see text)

Specimens, live (see text)

Background

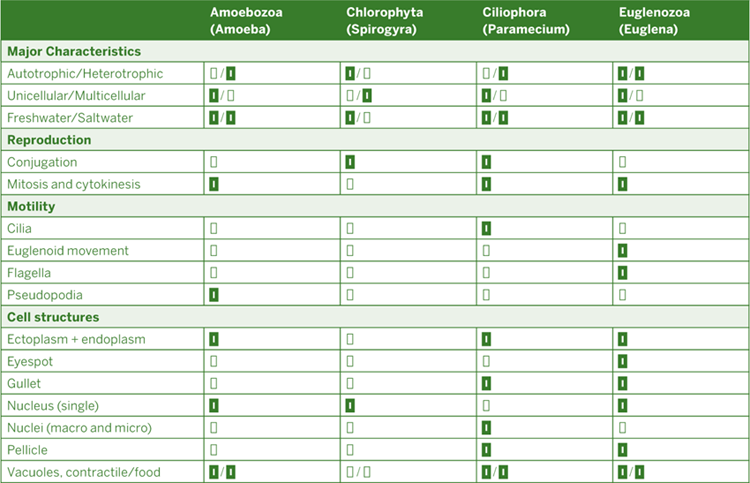

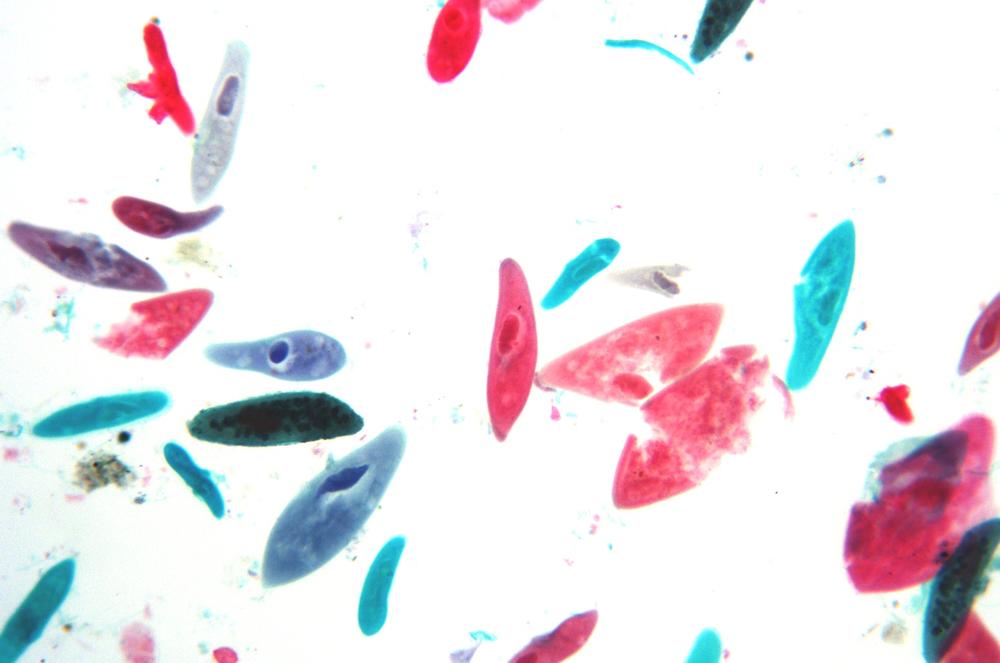

In this lab session, we’ll examine live specimens and prepared slides of a representative assortment of protista, focusing on the four species listed in Figure 29-1. We chose these four species because they illustrate a wide range of protist characteristics, and because they are ubiquitous and easily obtained from a nearby pond or one of the microcosms we built in an earlier lab session. (You can, if you prefer, instead purchase live protist cultures from Carolina Biological Supply or another full-range vendor, either separately or as mixed cultures.) Also, as common representatives of their respective phyla, most or all of these four species are usually included in standard prepared slide sets.

We’ll observe these protists in a particular order. First, Spirogyrae, which are plentiful and don’t move. Second, Euglenae, which are also plentiful and do move, but only slowly. Third, Amoebae, which are relatively rare (except in purchased cultures) and like to hide. Fourth, Paramecia, which are more or less plentiful (depending on the particular culture you use), but are so fast that they’re difficult to observe, particularly at higher magnifications.

If you don’t have prepared slides of any or all of these species, it’s easy to make your own. For Spirogyra and Euglena, make simple wet mounts. These species are easily visible without staining, although you can use methylene blue to stain the nuclei and eosin Y to stain the cell contents.

For Paramecium, use a clean pipette to transfer one drop of the culture liquid to each of two flat slides and spread the drop over the central part of the slide. Heat-fix the specimens. Observe one slide without staining. Stain the second slide with methylene blue and eosin Y and then observe the slide.

As the old joke goes, to make an Amoeba stew, first catch an Amoeba. Use a clean pipette to transfer several drops of the culture liquid to a deep well slide and observe the slide at low magnification (~40X) to see if one or more Amoebae are present. If one is, it’ll be obvious, because Amoebae are quite large. (Amobae like to hide near the bottom of the culture or in vegetation.)

Once you locate an Amoeba, while still observing through the microscope, squeeze the air out of a pipette, insert the tip into the slide well and suck up the Amoeba with at most a drop or two of liquid. Expel the liquid quickly onto a flat slide, while the Amoeba is still disoriented. (Amoebae like to glom onto things; we’ve seen them attach themselves to the inside of the plastic pipette, which doesn’t seem to offer much in the way of grippable surface.) Repeat to make a second Amoeba slide.

Gently heat-fix the slides, and stain one of them. Observe the Amoeba in unstained and stained versions.

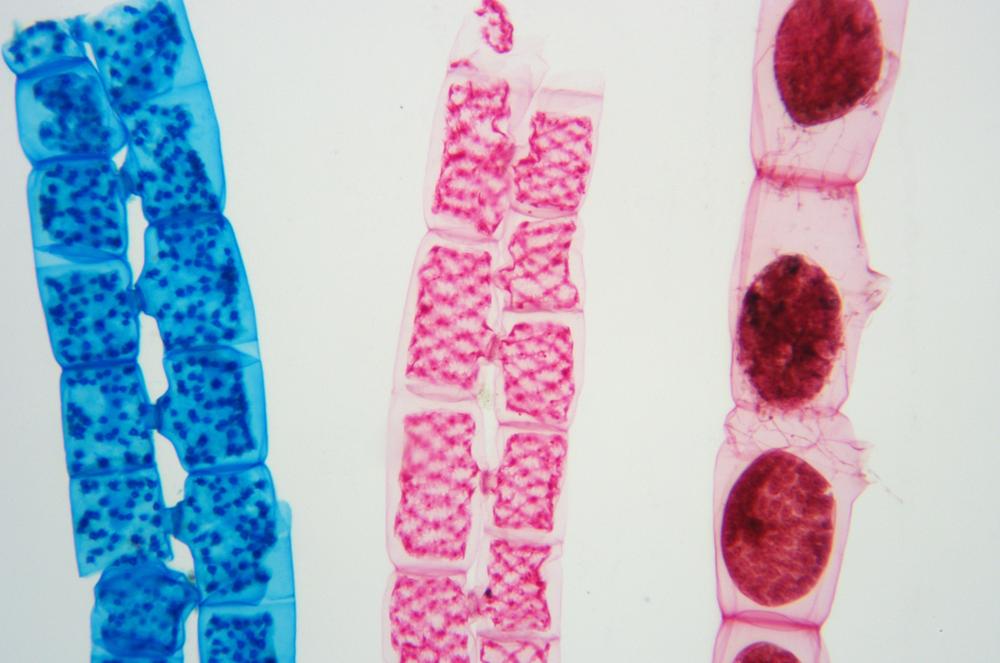

Procedure VIII-1-1: Observing Spirogyrae

Spirogyra is immediately recognizable as thin green unbranched filaments made up of a line of individual square or rectangular cells butted end-to-end. Most of the cellular features of Spirogyra are easily observed at low to moderate magnification and without staining. Begin at low magnification, and increase magnification as necessary to observe details of all of the features. As you observe your live and mounted specimens, look for the following features:

Cell wall – Spirogyra actually has a double cell wall. The outer layer is made up of pectin, which when wet forms a slimy gel. The inner layer, made up of cellulose, remains rigid even when wet. In live specimens, you’ll probably see only a single wall. In prepared slides, particularly if they are stained, the outer pectin wall may also be visible.

Cytoplasmic lining – a thin layer of cytoplasmic lining, also called the plasma membrane, exists on the inner side of the cell wall.

Vacuole – a large central vacuole is connected to the cytoplasmic lining by cytoplasmic strands. (The strands may be difficult to discriminate in unstained cells at low magnification.)

Nucleus – the cell nucleus is contained within the vacuole.

Chloroplasts – band- or ribbon-like chloroplasts are the most prominent feature of the cells. (Depending on the particular cell, the chloroplast(s) may appear scalloped or serrated rather than ribbon-like.) Any particular cell may contain anything from one to several chloroplasts.

Pyrenoids – these appear as small round dots on the chloroplasts, and are where starches are stored within the cells. Pyrenoids are usually readily visible in stained slides, but may be hard to discriminate in live specimens. If so, you can add a drop of Gram’s iodine stain to the slide. As the stain is absorbed by the cells, the starch present in the pyrenoids reacts with the iodine to form an intense blue-black color.

Spirogyra can reproduce asexually or sexually. In asexual reproduction, new filaments are formed by intercalary mitosis. Sexual reproduction in Spirogyra occurs via conjugation. In conjugation, one cell acting in the male role extends a tubular protuberance known as a conjugation tube. That tube links to a second cell, acting in the female role. Cytoplasm is transferred from the “male” cell to the “female” cell, where the “male” cytoplasm reacts with the “female” cytoplasm to produce a zygospore. (Note that cells are actually neither male nor female, but merely assume one of those roles during conjugative reproduction.)

Conjugation can occur between adjacent cells on a single strand (called lateral conjugation) or between two cells on different strands that are in close physical proximity (called scalariform conjugation). If you’re lucky, you may find conjugation occurring naturally in your live specimen. If not, you can encourage it to occur by adding a drop of sugar water to the slide.

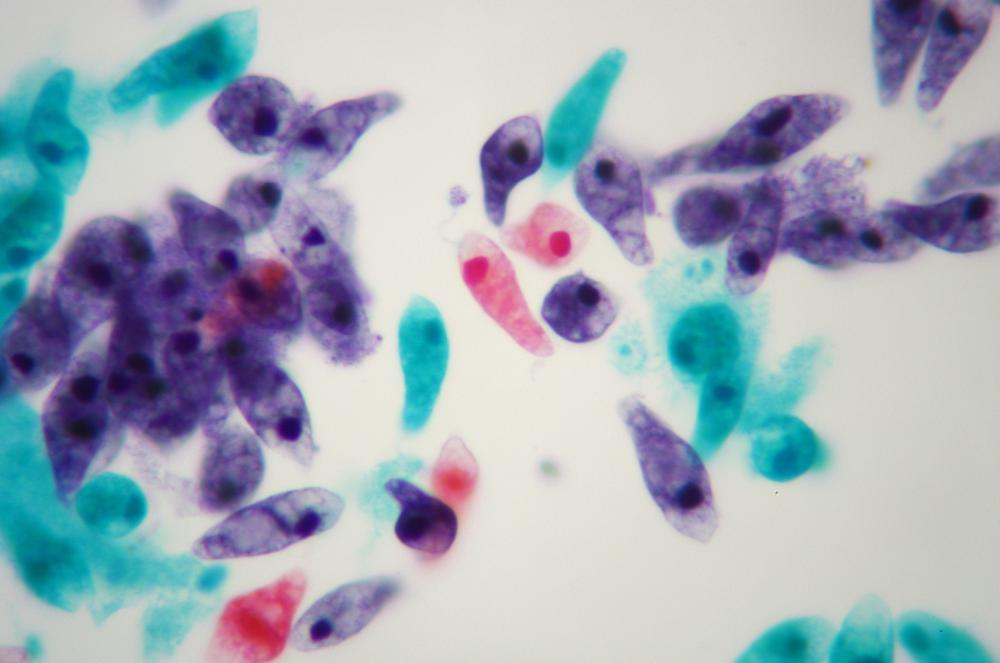

Procedure VIII-1-2: Observing Euglenae

From the large to the small. While Spirogyra forms filaments that are often visible to the naked eye, most Euglenoids are tiny creatures. (A few species are much larger, as much as 0.1mm in length, but these are very uncommon.) Euglenae are visible as tiny spots at 40X magnification. You may be able to see some detail at 100X, but observing full detail requires 400X or higher. If you have an oil-immersion objective (1,000X), now is a good time to use it.

Note

If you don’t have an oil-immersion objective but you do have a 15X eyepiece to substitute for the standard 10X eyepiece, you may find you can make out more detail at 600X than you can at 400X.

Euglenae hold an important place in the history of biological taxonomy. Beginning with Linnaeus, biologists classified living things in two kingdoms: Animalia, or animal-like creatures, and Plantae, or plant-like creatures. Protista were originally classified into one of these two kingdoms, with animal-like protists (such as Amoebae) classified in Animalia and plant-like protists (such as Algae) classified in Plantae.

Euglenae presented these early taxonomists with a real problem, because Euglenae were simultaneously animal-like (were motile and heterotrophic) and plant-like (possessed chlorophyll and were autotrophic). Accordingly, Euglenae were ultimately responsible for taxonomists expanding the original two-kingdom system to a three-kingdom system, with Euglenae and other protists classified in the new kingdom Protista.

Unlike Spirogyrae, Euglenae are motile. They use two methods of movement. First and more obvious is their constant alterations in shape, changing back and forth from an extended, worm-like form to a nearly circular form, a form of motion known as Euglenoid movement. Second, and less obvious, Euglenae possess flagella, tiny whip-like tails that they use to drive themselves from place to place.

Some of the cellular features of Euglena are visible at medium to high magnification without staining, but most are much more clearly visible in stained specimens. As you observe your live and mounted specimens, look for the following features:

Pellicle – one of the animal-like characteristics of Euglena is that it possesses no cell wall. Instead, the cell is contained within a pellicle, a membranous structure made up of proteins and supported by microtubules, which appear as a fur-like layer between the membrane and the interior cell components.

Nucleus – Euglena contains a single nucleus with an embedded nucleolus. With proper staining and at very high magnification, DNA strands may be visible as granularity or texturing within the nucleus, and ribosomal RNA as texturing within the nucleolus.

Chloroplasts – an individual Euglena may contain anything from one or two to several chloroplasts, visible as irregularly shaped flat or folded green structures.

Pyrenoids – pyrenoids are non-membrane-bound organelles within the chloroplast where photosynthesis occurs, producing a starchy polysaccharide called paramylon. Pyrenoids are present in and characteristic of the genus Euglena, but absent in other Euglenoids.

Food vacuoles – paramylon produced by the pyrenoids is stored in granules distributed throughout the cytoplasm. During periods of darkness, when photosynthesis cannot occur, the Euglena uses the starch stored in these vacuoles as an energy source.

Flagellum – the Euglena possesses a single flagellum, a thin, whip-like, nearly transparent structure that provides motility. The flagellum is often difficult or impossible to discriminate visually in live specimens with brightfield illumination, even at high magnification, but is often visible in live specimens with darkfield illumination or in stained specimens. You may be able to see flagella in live specimens under brightfield illumination if you use very dim lighting.

Reservoir – the reservoir is a bay-like indentation in the pellicle surface, open to the surrounding environment, where the base of the flagellum is rooted.

Contractile vacuole – the contractile vacuole is adjacent to the reservoir. This vacuole maintains osmotic equilibrium by gathering excess water from inside the cell and periodically expelling it via the reservoir to the exterior environment.

Paraflagellar body – the paraflagellar body is a light-sensitive organelle located within the reservoir at the base of the flagellum.

Stigma – the stigma, also called the eye spot or the red spot, works in conjunction with the paraflagellar body to allow phototaxis (movement toward a light source). As the Euglena moves, the stigma screens some light from the paraflagellar body, allowing the Euglena to determine the direction of the light source and move toward it.

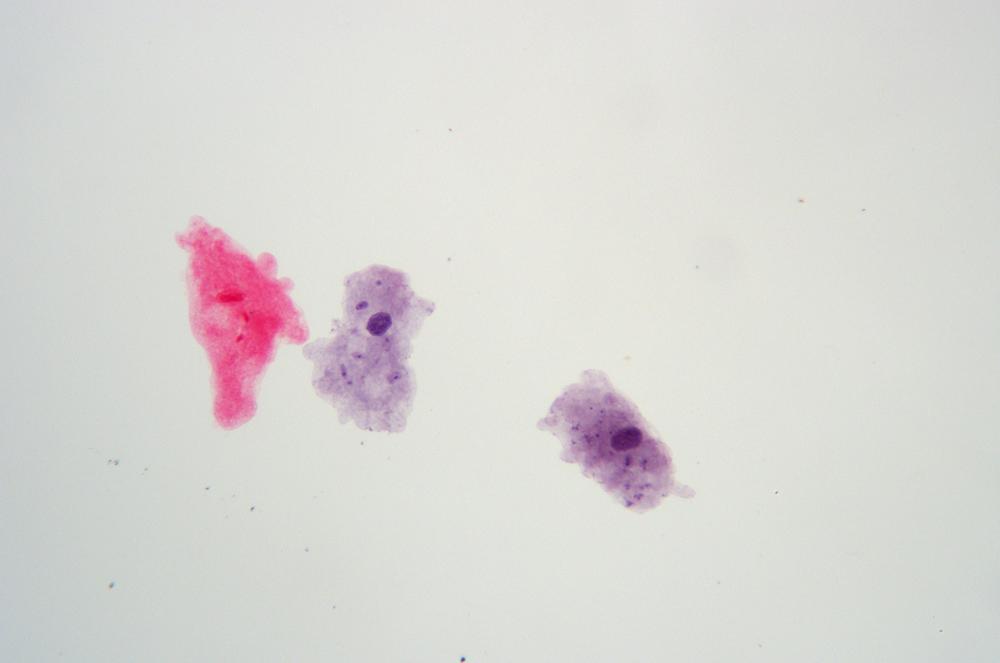

Procedure VIII-1-3: Observing Amoebae

From the small back to the very large. The Amoeba is certainly the most recognizable microorganism; even nonscientists can identify it immediately by its appearance. The Amoeba, or at least many of its species, is one of the largest microorganisms. Depending on species and the individual organism, some may be as large as a pinhead, and easily visible to the naked eye. Amoebae from other planets are apparently capable of eating entire buildings (cf. the 1958 horror/SF movie, The Blob, which featured one of these gigantic alien amoebae.)

Amoebae live in water, but are seldom found free-floating. Instead, they attach themselves to gravel, branches, leaves, or other solid materials. As heterotrophs, Amoebae must obtain nourishment from their environments. They do so by engulfing prey, including bacteria, other protists, and other tiny organisms.

An Amoeba moves by extending a pseudopod, with which it grasps the surface and then pulls the rest of the organism to the new location, a process called amoeboid movement or, more casually, oozing. (Not all microorganisms that use amoeboid movement are amoebae, but all amoebae use amoeboid movement.) Amoebae reproduce by mitosis and cytokinesis, a process that superficially resembles the binary fission by which prokaryotes (bacteria) reproduce. During reproduction, the nucleus splits in two and the cell “pinches” in until the pinched portion closes on itself and cuts the cell in two, forming two individual cells, which can then repeat the process to form four cells, and so on. If you’re patient while observing a live culture at low magnification, you may be fortunate enough to observe cytokinesis.

Note

So, if Amoebae can simply continue doubling their numbers by cytokinesis, why isn’t the surface of the planet covered with really, really old Amoebae? Unlike the Hydra, which does not experience senescence and so is immortal for all practical purposes, Amoebae do undergo senescence. The cytoplasm of vigorous young Amoebae appears almost transparent, while that of elderly Amoebae appears cloudy or chalky in comparison. Although cytokinesis can be thought of as an individual Amoeba cloning itself, that does not mean that those clones are immortal. An Amoeba that has not undergone cytokinesis recently gradually becomes senescent and may then fail to reproduce.

Most people’s initial impression of the internal structure of an Amoeba (or lack thereof) is that it is completely chaotic. In fact, Linnaeus originally assigned the binary name for the common Amoeba now known as Amoeba proteus as Chaos chaos. Because of its size, with proper lighting most of the cellular features of larger Amoebae are visible at low to medium magnification without staining, but most are much more clearly visible in stained specimens. As you observe your live and mounted specimens, look for the following features:

Cell membrane—like Euglena, one of the animal-like characteristics of Amoeba is that it possesses no cell wall. The amoeba’s cytoplasm—ectoplasm and endoplasm—and organelles are contained within a soft cell membrane.

Cytoplasm – Amoebae contain two types of cytoplasm. Ectoplasm is found adjacent to the cell membrane. It is clear and has a jelly-like consistency. Endoplasm fills the cell inside the ectoplasm. It is thin and watery and has a granular appearance. Various organelles float within the endoplasm.

Nucleus – Amoebae contain one nucleus. (Some members of the amoeboid genus Chaos contain 1,000 or more nuclei.)

Food vacuoles – Amoebae feed on microorganisms by engulfing them. These prey are stored and digested in organelles called food vacuoles.

Contractile vacuole – the contractile vacuole in Amoebae is similar in appearance and function to the same organelle in Euglenae. It maintains osmotic equilibrium by gathering excess water from inside the cell and periodically expelling it to the exterior environment.

Procedure VIII-1-4: Observing Paramecia

The paramecium is the sprinter of this group. Spirogyrae are not motile. Amoebae slowly ooze from place to place. A Euglena, with its single flagellum, might achieve speeds of 100 μm/s or a bit more, taking about 10 seconds to move a single millimeter. But the Paramecium—with its thousands of cilia beating synchronously like thousands of tiny rowers—has been clocked at speeds of 2,000 μm/s, which means it can move completely though a microscope’s field of view in a small fraction of a second.

That means observing live Paramecia is challenging, to say the least. You can slow them down significantly by adding a drop of methylcellulose or glycerol to the drop of culture liquid, or by placing a tiny tuft of cotton fibers in the drop of culture to present a physical barrier to their movement. Even then, it’s almost impossible to observe fine detail. For that, you’ll need a prepared slide.

Paramecia reproduce both sexually and asexually. In sexual reproduction, called conjugation, two individuals align longitudinally and exchange nuclear material. In asexual reproduction, called transverse fission, one individual splits laterally, with the macronucleus and cell body dividing in two and the micronucleus replicating by mitosis. Fission occurs much more commonly than conjugation, but if your live culture contains numerous individuals you may have the opportunity to observe both forms of reproduction.

As you observe your live and mounted specimens, look for the following features:

Pellicle – like the Euglena, the Paramecium is contained within a pellicle, but while the Euglena pellicle is extremely flexible, allowing the Euglena to change shape radically, the Paramecium pellicle is relatively rigid, forcing the creature to maintain its slipper-like shape.

Cilia – the surface of the paramecium is covered with thousands of hair-like cilia, which beat synchronously. Like the flagellum of a Euglena, cilia provide motility, but because they are present in much higher numbers, the Paramecium can move much faster than a Euglena.

Cytoplasm – Paramecia contain two types of cytoplasm. Ectoplasm is found adjacent to the pellicle. Endoplasm fills the cell inside the ectoplasm, with various organelles floating with it.

Nucleus – The other three protists we’ve examined each has a single nucleus. Paramecia have two nuclei, each of which has different duties. The macronucleus handles routine tasks such as metabolism. The micronucleus, much smaller than the macronucleus, is responsible for reproduction.

Oral grove/mouth pore/gullet – this is a prominent internal structure, beginning near the anterior end of the creature and extending about half its length. Cilia in the oral groove sweep bacteria and other unicellular prey through the mouth pore and into the gullet, also called the cytopharynx. When sufficient food organisms have been gathered in the gullet, they are expelled into the endoplasm as a food vacuole.

Food vacuoles – when the cytopharynx is filled with prey, it expels a food vacuole, also called a phagocytic vacuole, into the endoplasm. The food vacuole travels the length of the creature, with digestion enzymes acting on the contents of the vacuole. By the time the food vacuole has finished its journey, it has shrunk considerably and contains only waste materials. When the food vacuole reaches the anal pore, it ruptures and expels the waste materials to the outside environment.

Contractile vacuoles – the Paramecium is contained within a semi-permeable membrane, which passes water freely. The anterior and posterior contractile vacuoles maintain osmotic equilibrium by gathering excess water from inside the cell and periodically expelling it to the exterior environment.

Review Questions

Q1: What visual evidence suggests that Spirgoyra and Euglena are autotrophic?

Q2: What additional information might we gain by observing all four of these species in a mixed culture rather than observing individual cultures of each species?

Q3: What differences, if any, did you observe in the motility and motility mechanisms in the different species? Which are the fast and slow movers?

Q4: In the original two-kingdom system (Animalia and Plantae), to which of those kingdoms do you think Algae, Amoebae, and Paramecia were assigned? Why? Using the Internet or other resources, identify a class of organisms that was originally assigned to Plantae, later to Fungi, and now to Protista.

Q5: Using the Internet or other resources, identify a group of organisms that was originally assigned to Plantae, later to Fungi, and now to Protista.