Chapter 36. Investigating Vertebrate Tissues

Equipment and Materials

You’ll need the following items to complete this lab session.

Materials from Kit

None

Materials You Provide

Microscope

Slides, prepared, Vertebrata (see text)

Background

Vertebrates are members of the subphylum Vertebrata of the phylum Chordata. Vertebrates are the organisms that most people think of as animals, including the classes fish, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals.

The defining characteristic of vertebrates is their possession of a vertebral column (or spine) consisting of a segmented series of hard, bony vertebrae (singular vertebra) separated by intervertebral discs, which provide mobility and allow the spine to move and flex. (In other chordates, the spine is a stiff rod of uniform composition that is incapable of flexing.) Vertebrates are also the only members of Animalia that possess true brains.

There are many differences among vertebrates. For example, some are oviparous (giving birth to eggs that subsequently hatch into live young) while others are viviparous (giving birth to live young). Some vertebrates are ectotherms (cold-blooded) while others are homotherms (warm-blooded). But the similarities among vertebrates—particularly within classes, but even across classes—are much greater than the differences.

In studying vertebrate structures, it’s convenient to treat them as a hierarchy: a collection of cells forms a tissue; a collection of tissues forms an organ; and a collection of organs forms an organ system. For example, a collection of cardiac muscle cells makes up cardiac tissue, and a collection of cardiac tissues make up the heart, which in turn is part of the circulatory system.

Form (macro- but particularly micromophology) often follows function. Despite sometimes gross morphological differences across species and even classes, the analogous organs perform very similar functions and so tend to resemble each other, more or less. For example, it is difficult or impossible for someone who is not a vertebrate anatomist to distinguish between, say, cross-sections of a fish liver and a mammal liver, and even that anatomist might be unable to distinguish readily between cross-sections of a pig liver and a chimpanzee liver.

All vertebrate organs are made up of one or more of the four basic tissue types:

- Epithelial tissues

Epithelial tissues cover the surfaces and cavities of body structures, and also form many endocrine and exocrine glands. For example, your skin, the inside of your mouth, and your stomach, liver, and pancreas are made up, in whole or in part, of epithelial tissues. Epithelial tissues perform four general functions. First, they protect underlying tissues from dehydration and physical damage. Second, they provide a selectively permeable barrier that prevents or allows the passage of particular molecules, such as water or nutrients. Third, they secrete specific fluids, such as digestive fluids. Fourth, they provide sensory inputs to the nervous system.

- Connective tissues

Connective tissues are found throughout vertebrate bodies, serving in many roles. Bone and bone marrow, cartilage, tendons, adipose tissue, and blood are just some examples of structures made up partially or entirely of connective tissue.

- Muscle tissues

Muscle tissues are made up of muscle cells, which contain contractile filaments that can contract and expand to change the sizes and shapes of muscle cells. Muscle tissues are classified as cardiac muscles, smooth muscles, or skeletal muscles. The first two types are not under voluntary control, and perform such functions as circulating blood, moving food through the digestive tract, and dilating or contracting pupils in response to changing light levels. Skeletal muscles are under voluntary control and are used to move the body, from tiny motions such as shifting your eyes to gross movements such as kicking a soccer ball. (Some muscular activity—such as focusing your eyes, breathing, or urinating—take place under partial voluntary control and partial involuntary control.)

- Nervous tissues

Nervous tissues are the primary component of the brain, spinal cord, and nerves, which together regulate body functions, including thought. Nervous tissues are made up of neurons, which transmit electrical impulses, and neuroglia cells, which support the neurons. Although all cells have the ability to react to external stimuli, the cells that make up nervous tissues are adapted to transmit impulses over long distances to whichever organs are responsible for dealing with the specific stimulus.

As you work on each procedure, use your textbook or Internet resources to determine which features, structures, organelles, and so forth to look for. For example, when you are examining slides of epithelial tissues, compare and contrast simple, stratified, and pseudostratified epithelial tissues, and do the same for squamous, columnar, and cuboidal epithelial cells. Identify the basement membrane and any glands present in the epithelial tissue, and note the presence or absence of blood vessels. Record your observations in your lab notebook. Sketch or shoot images of any significant features you observe.

Note

Although nervous impulses are electrical, they propagate at a tiny fraction of the speed of electrical impulses in copper wire or similar conductors. Electrical impulses in insulated wire typically propagate at about 0.7 light speed or roughly 210,000,000 m/s, millions to billions of times faster than the electrical impulses in nerves, which propagate at between 0.1 m/s and 100 m/s.

That’s why it takes a noticeable fraction of a second for the reaction when someone taps your knee to test your reflexes. The major reason for that delay is that your nervous system isn’t a bunch of individual wires. Instead, it’s zillions of nervous cells that are connected together and function more like a bucket brigade than a cable. One cell delivers the message to the adjoining cell, which turns around and delivers the message to the next cell in line, with a lag involved at each step along the way.

Note

To minimize the number of prepared slides required, we’ve included many images in this lab session. As always, remember that images are not perfect substitutes for viewing actual slides, so we recommend that you obtain as many prepared slides as possible and use the images only to fill in for slides you don’t have.

The standard kit for this book, available from www.thehomescientist.com/biology.html, includes a disk with high-resolution JPEG files of the photomicrographic images used in this book. Those images can be viewed on any PC (Windows, Mac OS X, or Linux) or tablet.

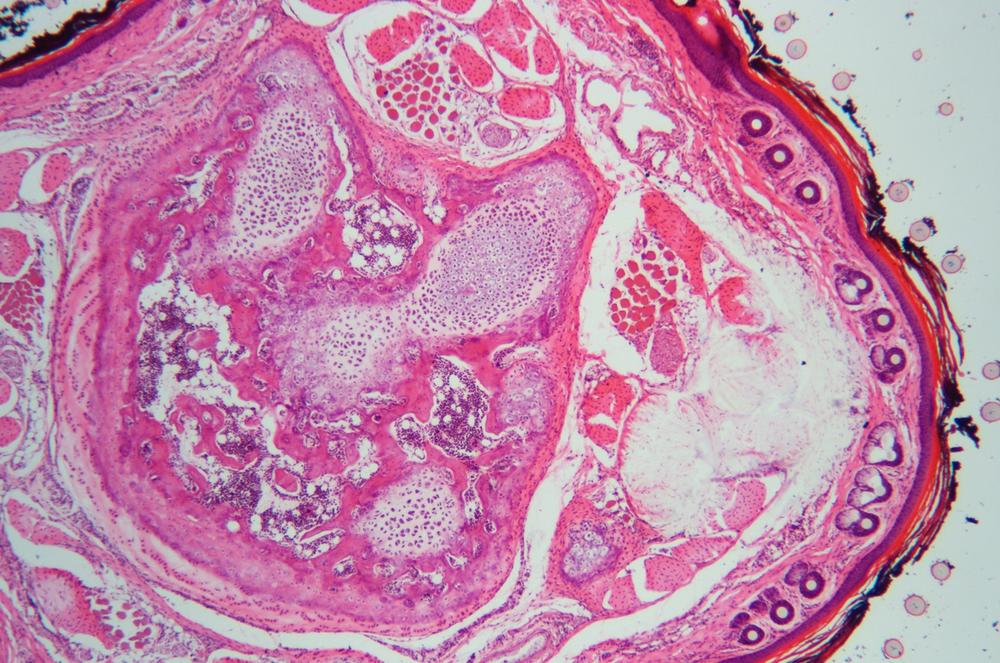

Procedure XI-4-1: Observing Epithelial Tissues

Epithelial cells and tissues are found throughout vertebrate bodies. Epithelial structures are classified by cell type and tissue layer type:

Squamous epithelial cells are flat and resemble fried eggs.

Cuboidal epithelial cells resemble dice in whole mounts or squares in sectional mounts.

Columnar epithelial cells in longitudinal sections resemble tall, narrow columns, but in cross-section they may be confused for squamous or cuboidal cells.

These epithelial cell types may be organized in the following ways:

Simple epithelium has only one layer, which may comprise any of the types of epithelial cells, and is found in tissue that performs absorption or filtration functions. The cell layer in simple epithelium is in direct contact with the basement membrane.

Stratified epithelium has two or more layers above the basement membrane, may comprise any combination of epithelial cell types, and is found in any type of tissue that must be resistant to physical abrasion or chemical attack.

Pseudostratified epithelium has only one columnar cell layer, but the locations of the nuclei of those cells may make it appear in sectional mounts that the epithelium is stratified.

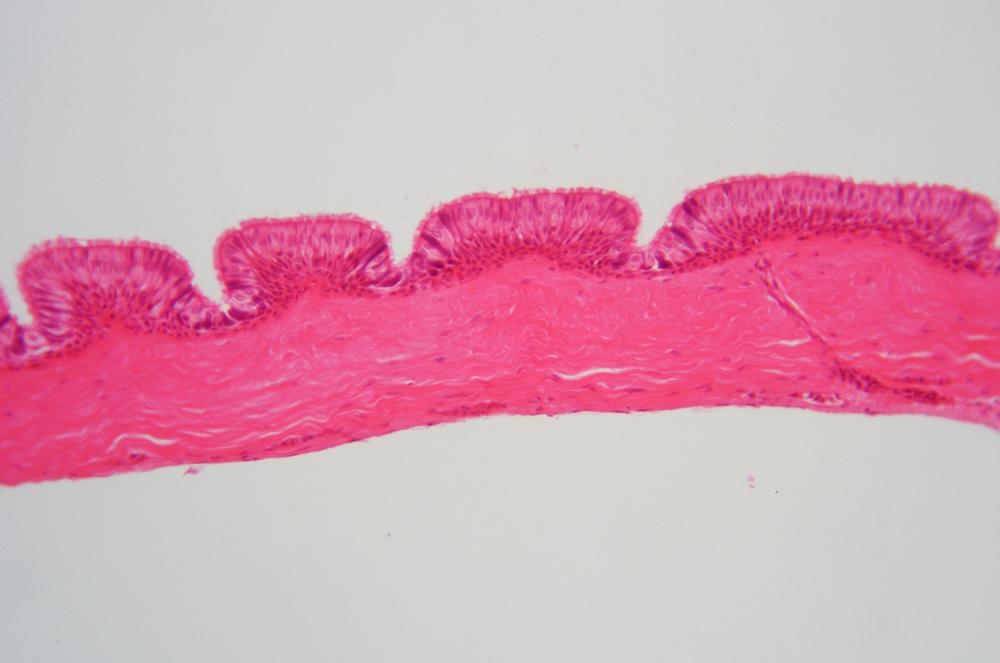

Ciliated epithelium is a type of pseudostratified epithelium in which the outward-facing membrane possesses tiny hair-like structures called cilia. Cilia may function as extra-cellular sensors, and may also provide propulsive functions such as moving ova from the ovary down the Fallopian tubes to the uterus or distributing mucus produced by goblet cells in the epithelial tissue.

Glandular epithelium—found in endocrine glands, exocrine glands, and other organs—is made up of highly adapted epithelial cells that do not function as a protective layer. Instead, these cells produce hormones, milk, mucus, digestive fluids, sweat, and other substances.

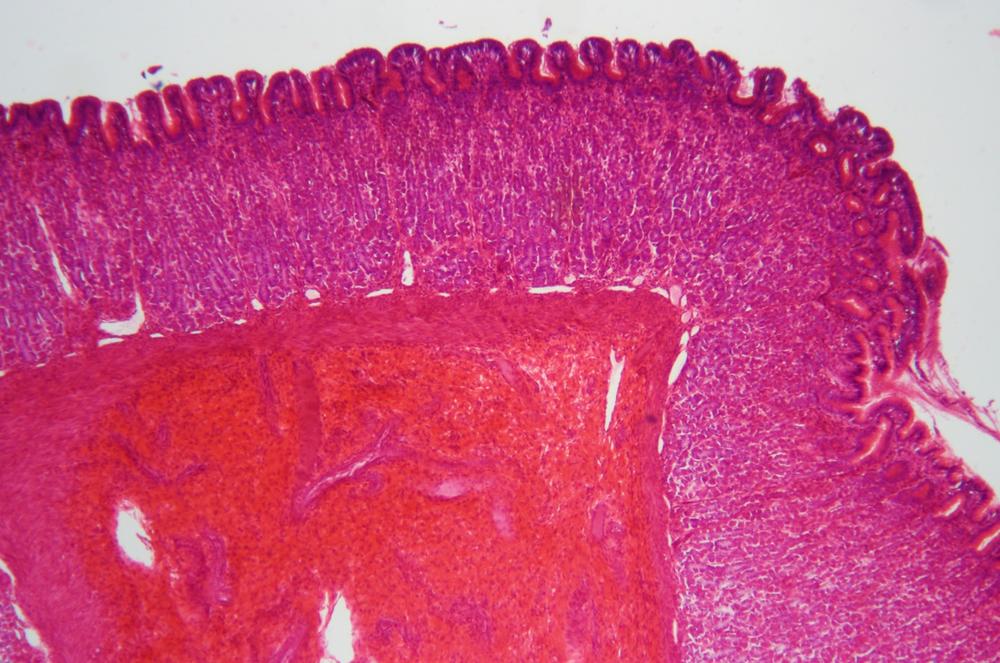

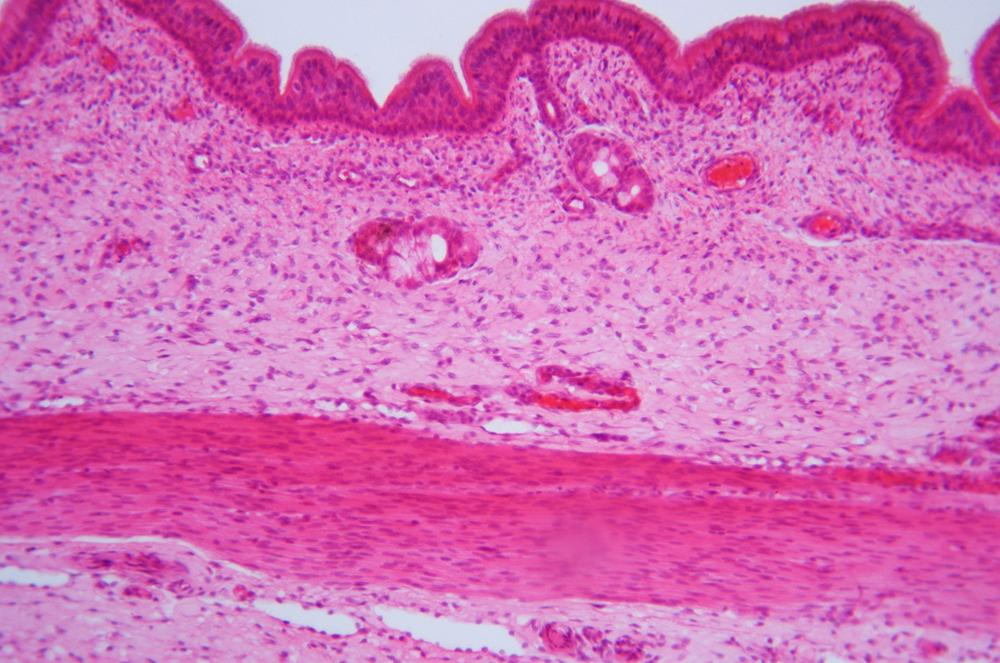

Examine prepared slides showing the various types of epithelial cells and epithelial structures. As you examine each slide, identify the epithelial cell types present and their arrangement. Figure 36-1 through Figure 36-21 show examples of epithelial cell types and numerous epithelial structures.

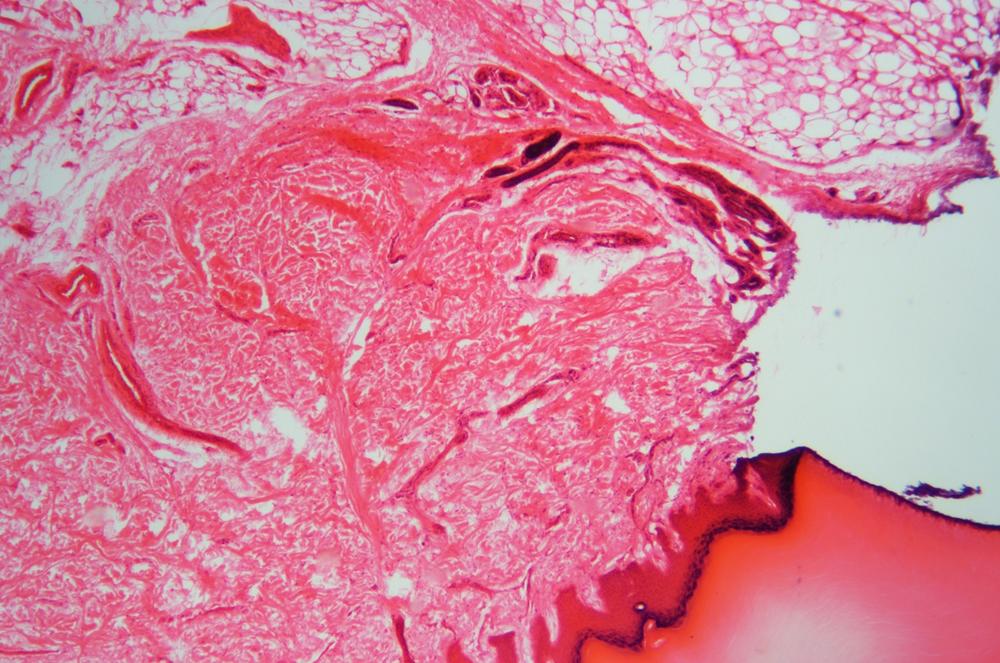

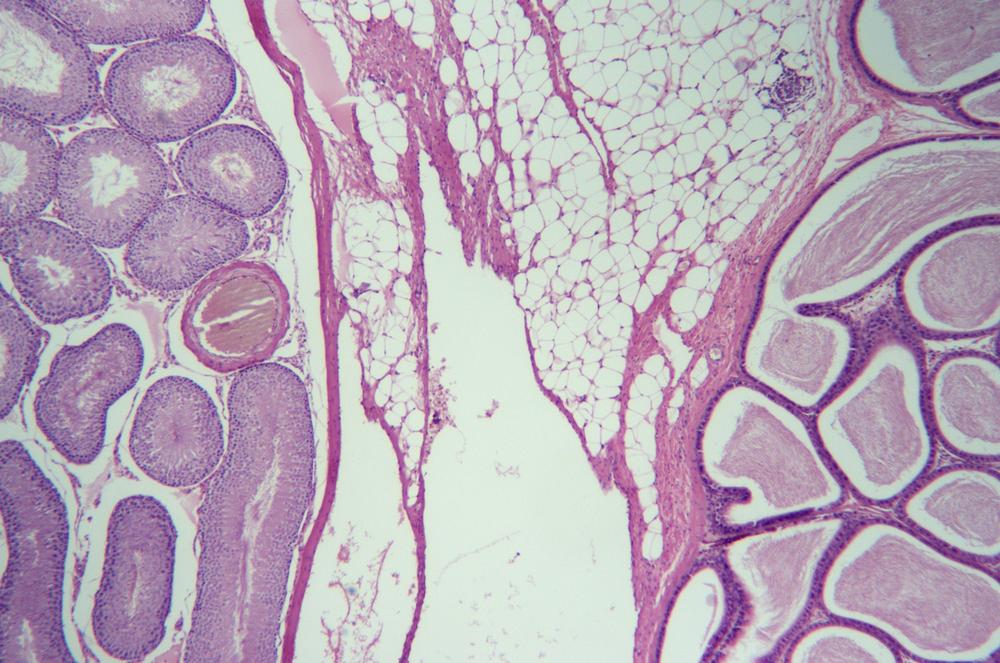

Various vertebrate classes have adapted by forming specialized exterior surface epithelial structures such as the scales of fish, the feathers of birds, and the hair of mammals. Examine prepared slides of as many of these structures as you have available, and consider how the morphology of the various structures is adapted to suit particular functions. Figure 36-22 through Figure 36-26 show several of these specialized structures.

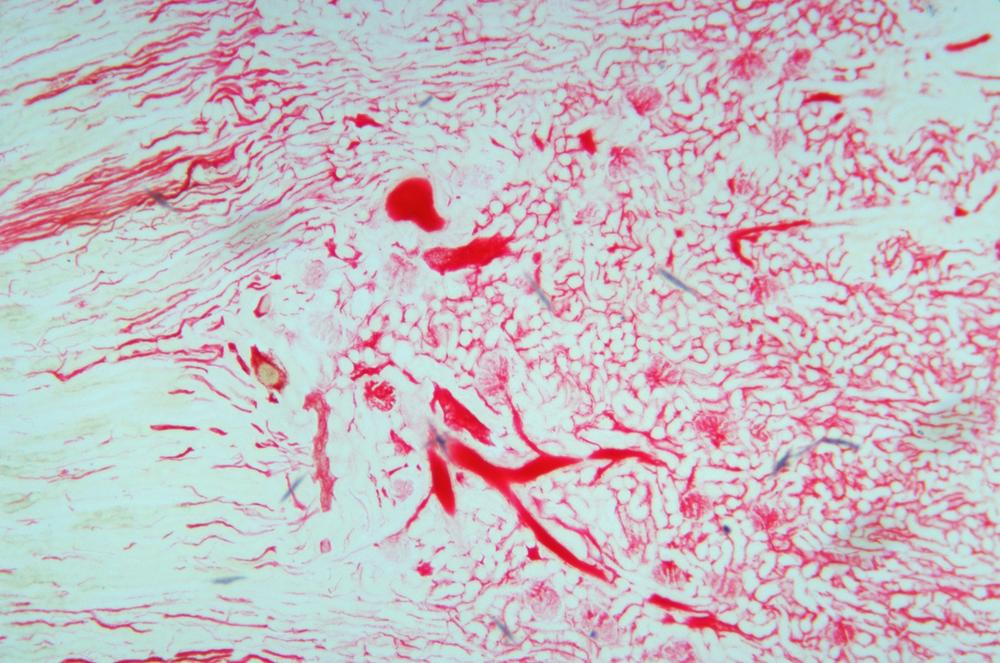

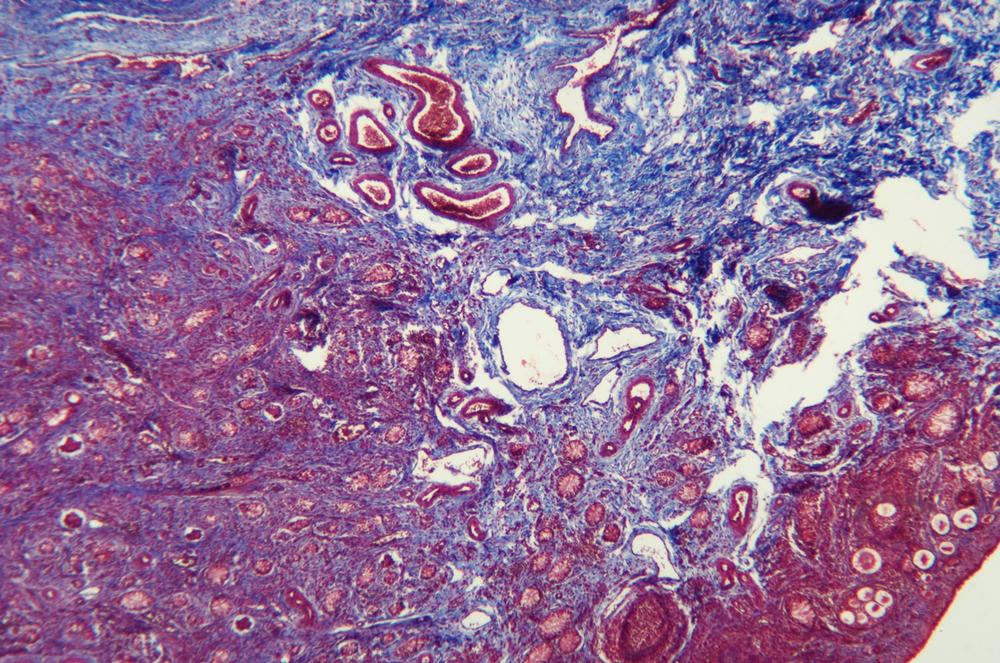

Procedure XI-4-2: Observing Connective Tissues

Connective tissue (CT) is the most diverse of the four tissue types, and is found throughout vertebrate bodies. CT performs numerous functions, including providing a structural framework for the body, storing food energy, protecting organs against physical damage, and distributing oxygen to and removing carbon dioxide from other tissues and organs.

CT is made up of specialized cells and an extracellular matrix produced by those cells. That matrix is made up of a transparent, homogeneous liquid known as ground substance and fibers of any of three types: collagenous fibers, elastic fibers, and reticular fibers. These fibers strengthen the CT in the same way that rebar strengthens reinforced concrete. Because they can be stretched and then return to their original shape and size, elastic fibers provide flexibility to CT.

Connective tissue makes up numerous body structures in whole or in part, including adipose tissue; blood and lymphatic tissue; bones and bone marrow; the capsules, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons that support the skeleton; and the fibrous framework of muscle tissues. There are three categories of connective tissue.

- Embryonic connective tissue

Embryonic connective tissue occurs in two subtypes, mesenchyme and mucoid, both of which are made up of mesenchymal cells and reticular fibers embedded in ground substance. Mesenchymal cells are pluripotent (undifferentiated juvenile) cells, which can be triggered to form various types of adult cells, including adult connective tissue cells. Mucoid CT, found in the umbilical cords of mammals, is very similar to mesenchyme CT, but with a much sparser distribution of cells and fibers. Because reticular fibers are invisible without special staining, embryonic CT (ECT) is normally visible in standard prepared slides as only an apparently random scattering of cells in a clear background of ground substance.

- Ordinary connective tissue

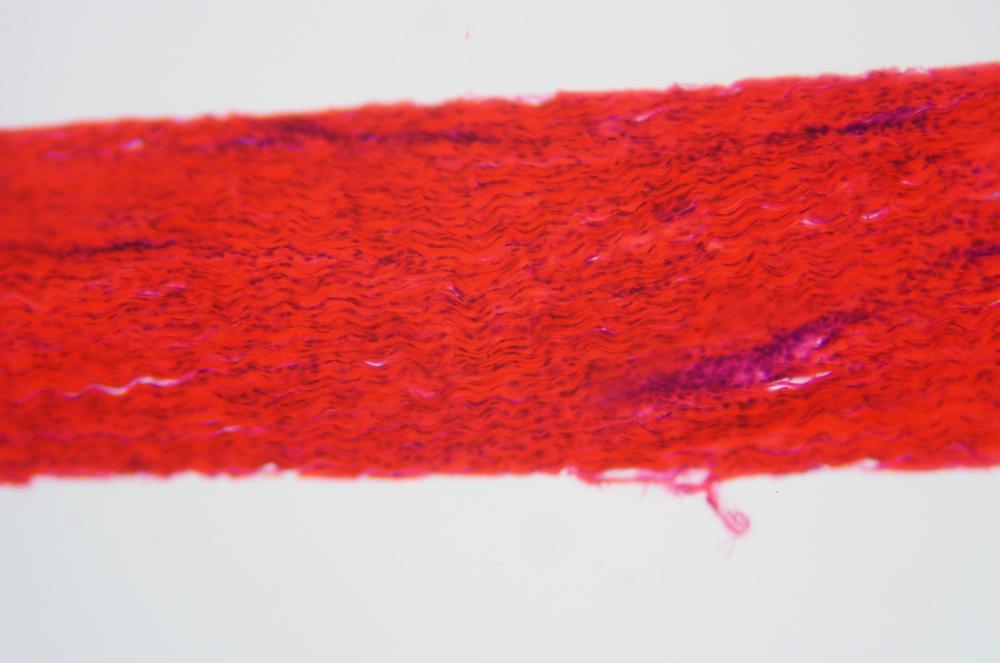

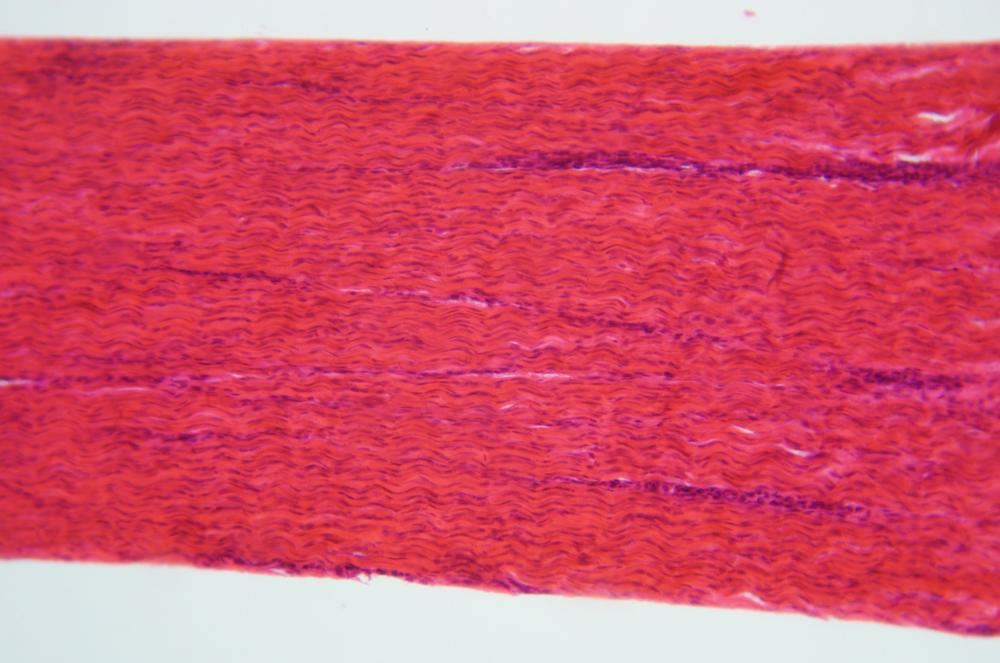

Ordinary connective tissue (also called proper connective tissue) subtypes include loose connective tissue, also called areolar connective tissue, and dense connective tissue, which is further subdivided into regular dense connective tissue and irregular dense connective tissue. Loose CT is found throughout the body, surrounding and providing support for other structures, such as nerves and blood vessels, as well as anchoring and binding together other tissues and organs. Dense CT, found in tendons and similar structures, has a much higher density of collagen connective fibers.

- Special connective tissue

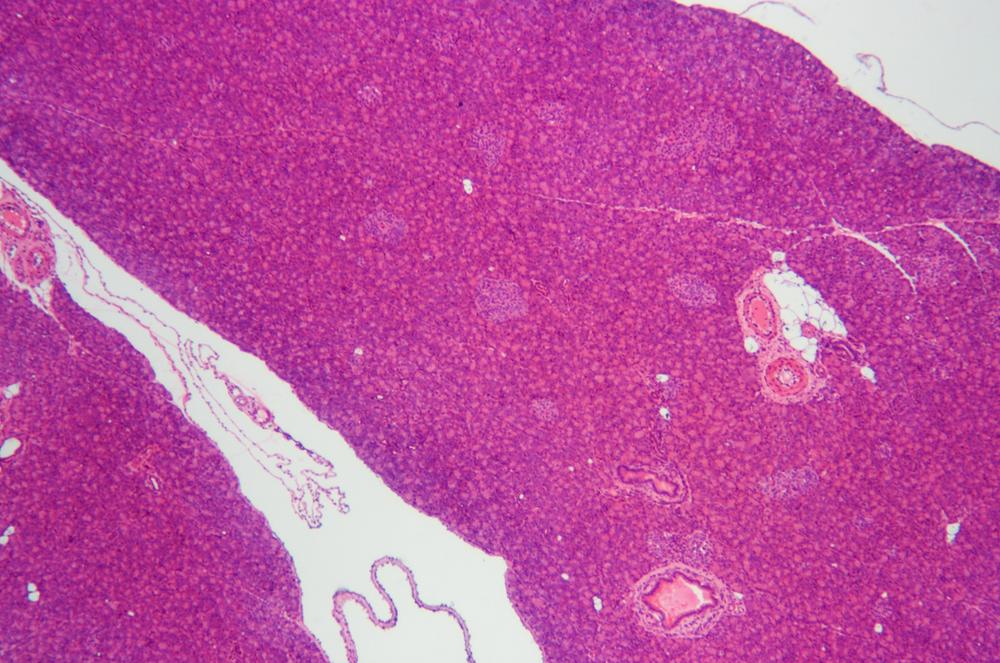

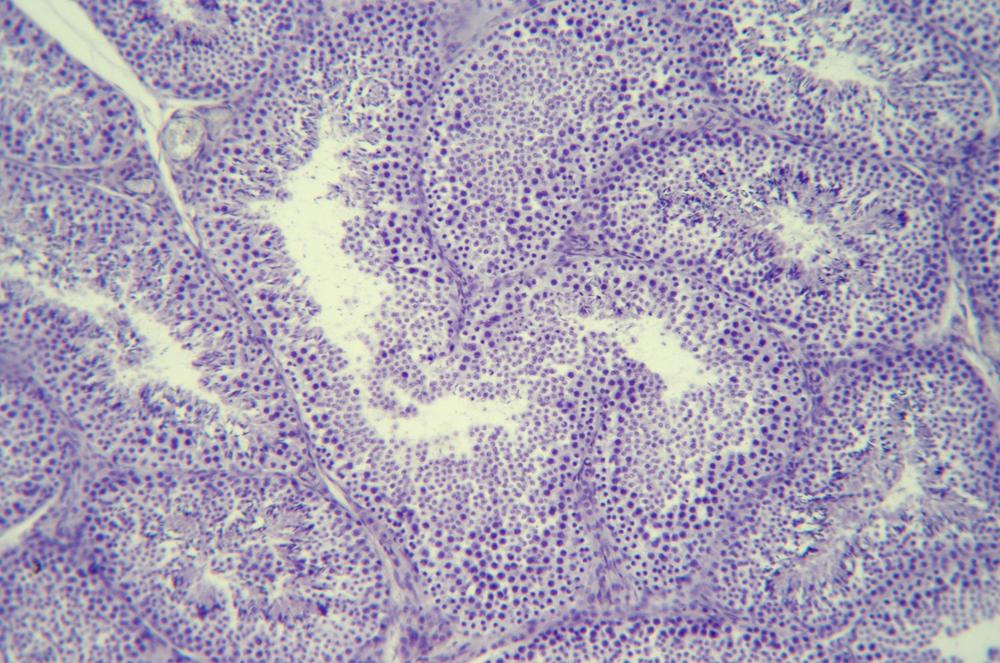

Special connective tissue subtypes include adipose (fatty) tissue, blood, bone, cartilage, hematopoietic tissue (bone marrow), and lymphatic tissue, each of which has a characteristic extra-cellular matrix.

Note

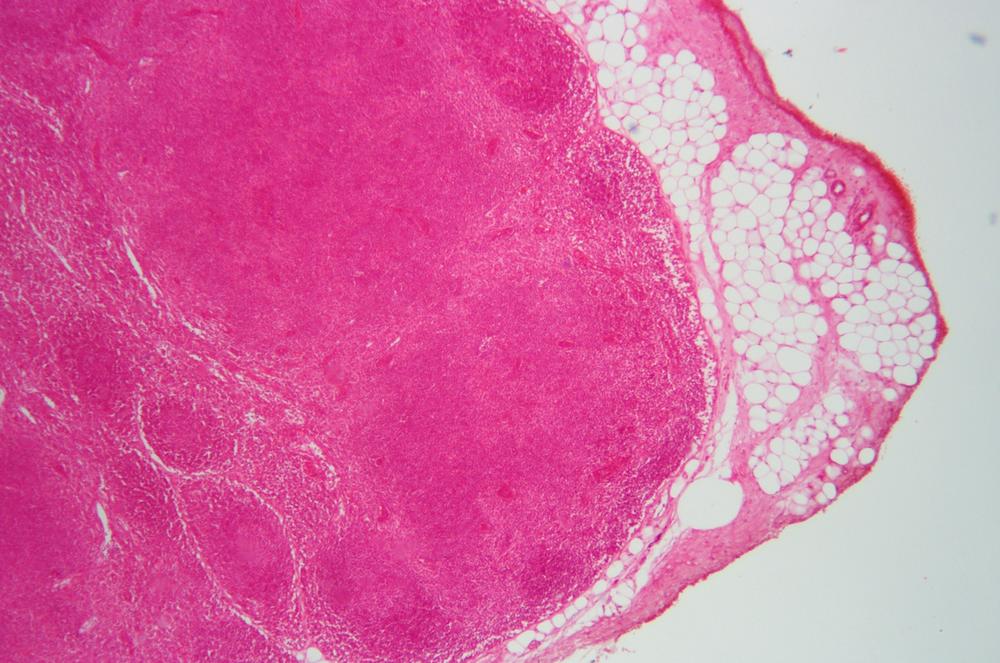

Although adipose tissue is classified as a special CT, it is found in conjunction with loose CT, which supports the fatty adipose cells (visible in Figure 36-28, Figure 36-31, and many other figures in this session). At first glance, an adipose cell may appear to be just a cell membrane with no nucleus or other contents. In fact, the center of the adipose cell is occupied by lipids (fats), which push the nucleus to the edge of the cell, where it is visible in suitably stained sections as a tiny dark spot.

Examine prepared slides showing loose and dense connective tissue. Figure 36-27 through Figure 36-30 show examples of these types of connective tissue.

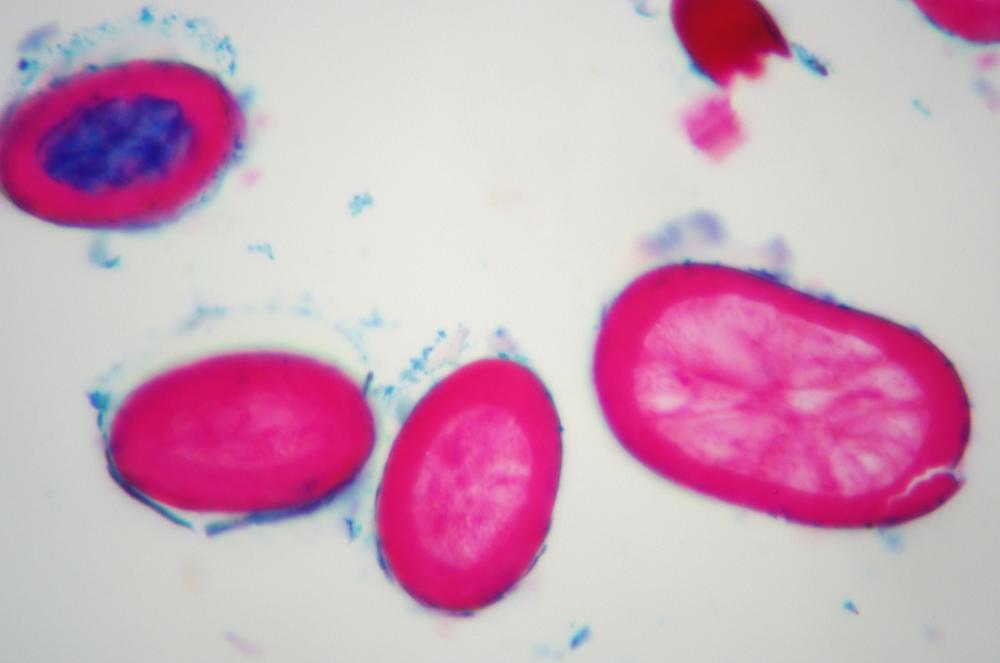

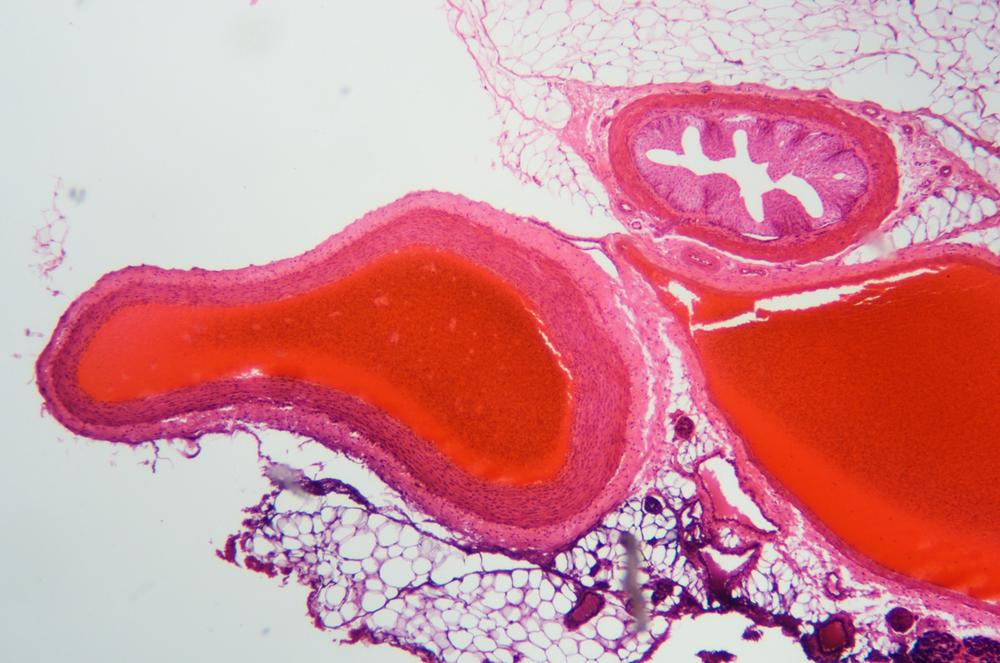

Although it may seem odd to classify blood as a special connective tissue, that is in fact what it is. Like other special CTs, blood consists of individual specialized cells rather sparsely distributed in an extra-cellular matrix. For blood, that matrix is called plasma.

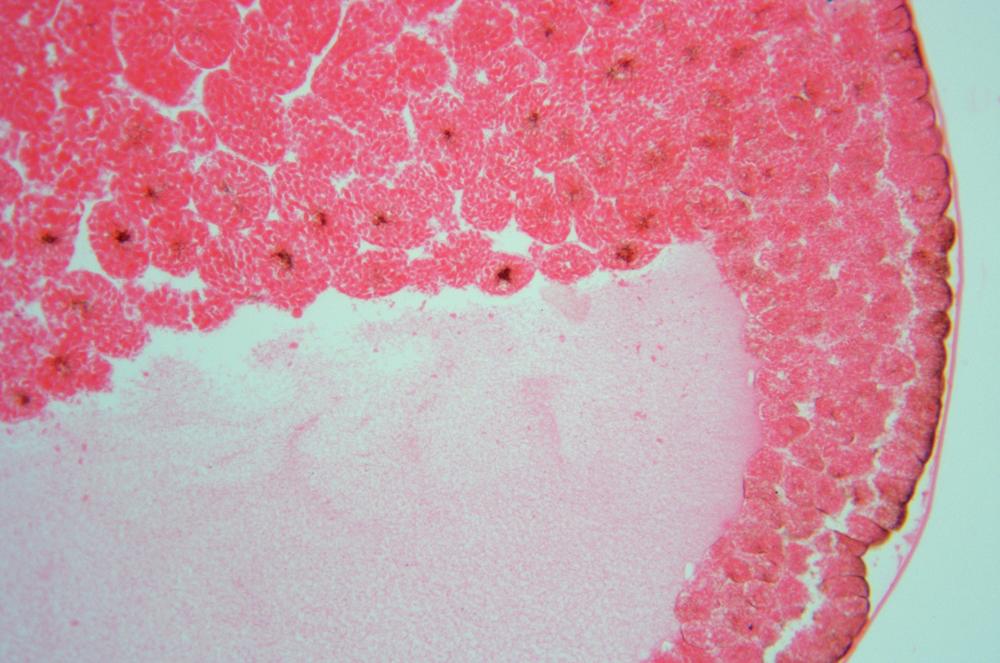

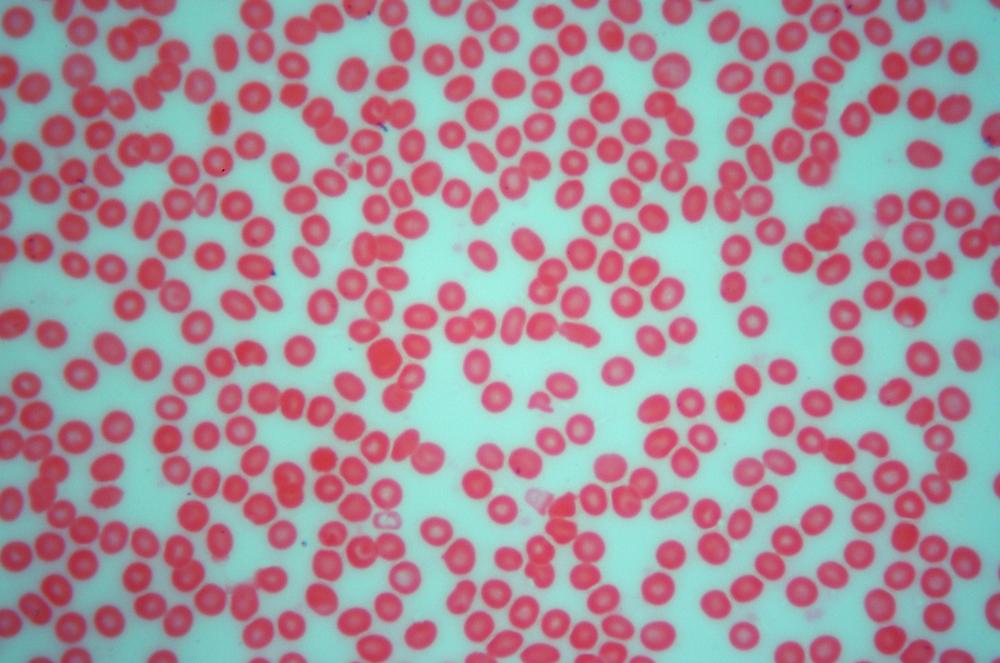

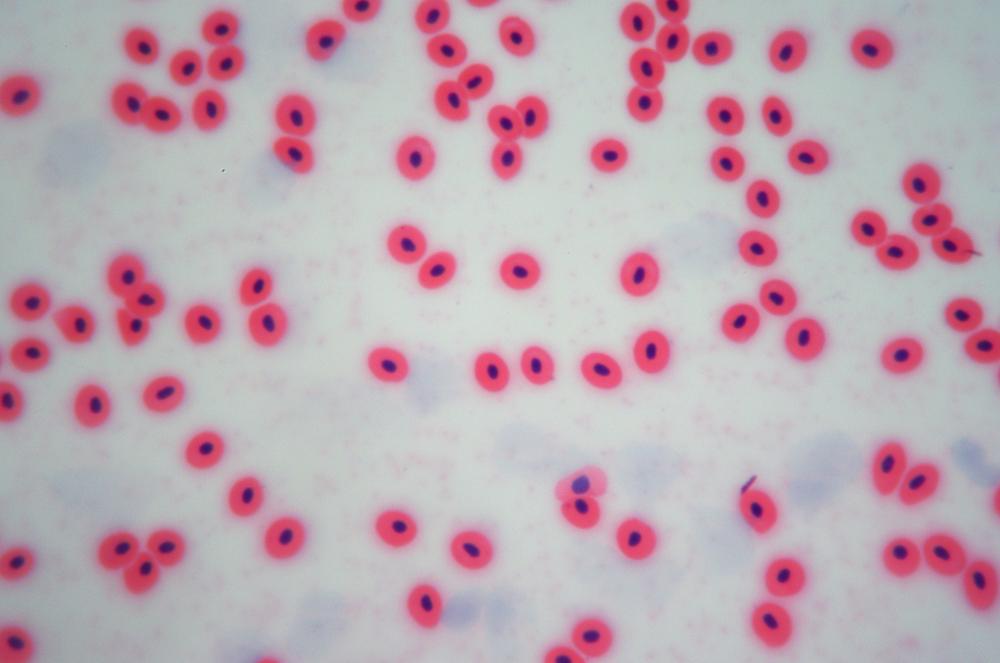

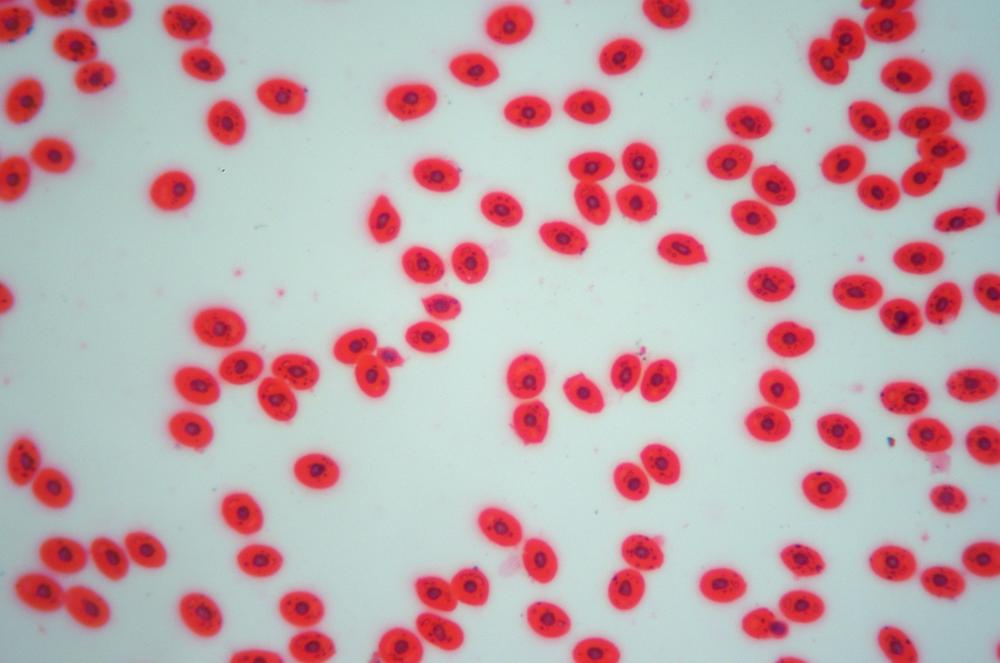

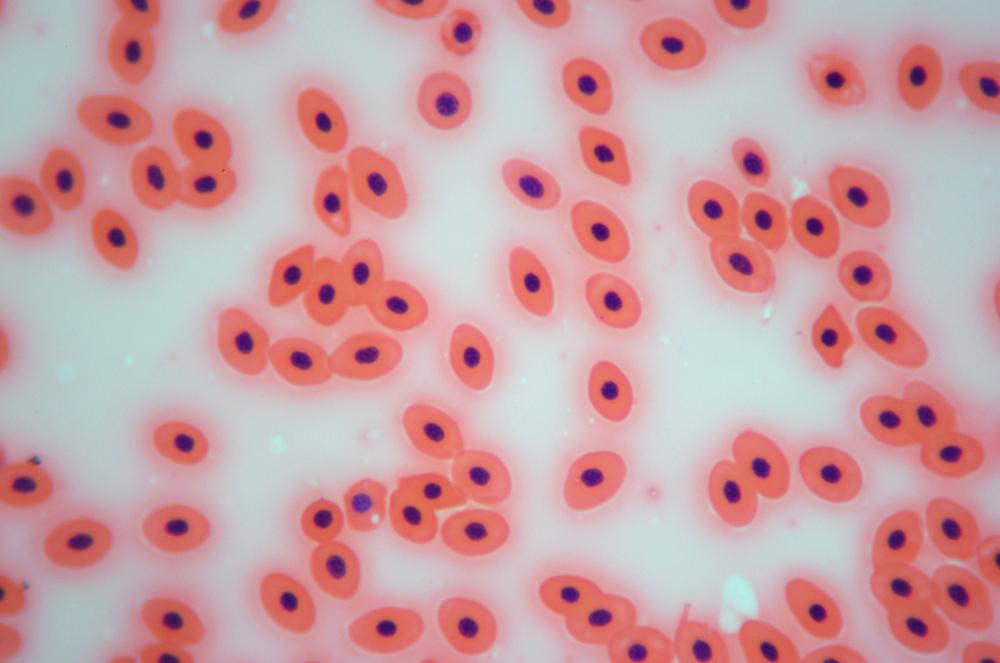

Erythrocytes or red blood cells—which carry oxygen to the body’s cells and carbon dioxide away—are by far the most common cell type found in blood. Leukocytes or white blood cells—which are part of the immune system—are much less numerous, as are tiny platelets, which are anuclear fragments of bone marrow cells that assist in blood clotting.

Examine a prepared slide of a human blood smear. Identify erythrocytes (numerous, small, and of regular shape), leukocytes (relatively rare, larger, and of less regular shape), and platelets (relatively rare, tiny, and irregular). Examine other prepared slides of blood smears from other vertebrates. Figure 36-32 through Figure 36-35 show examples of blood from several species.

Note

The red color of the cells in these figures results from staining, which obscures the actual color.

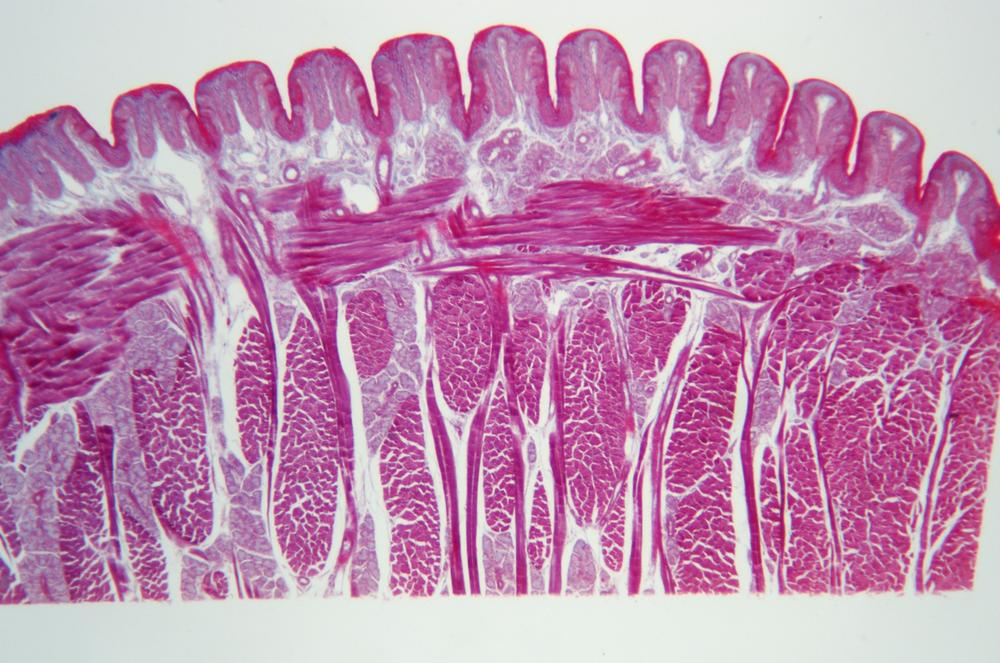

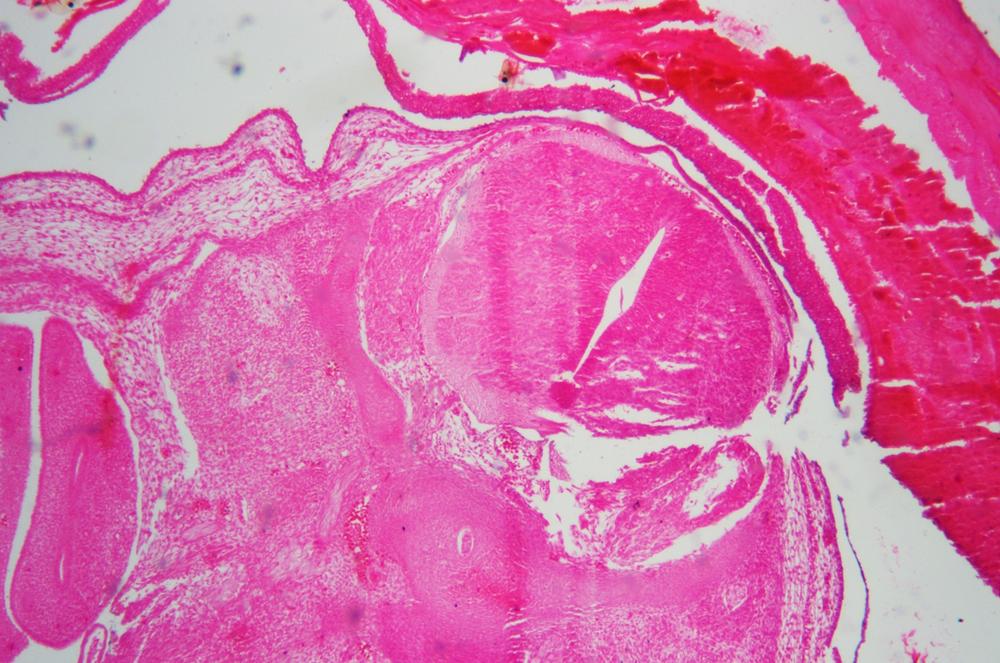

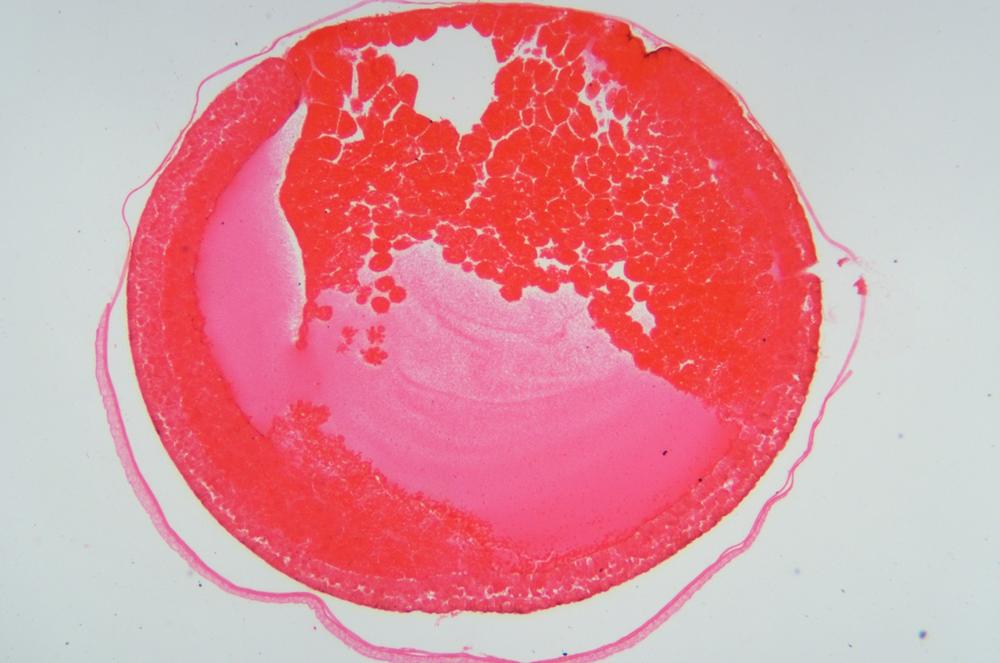

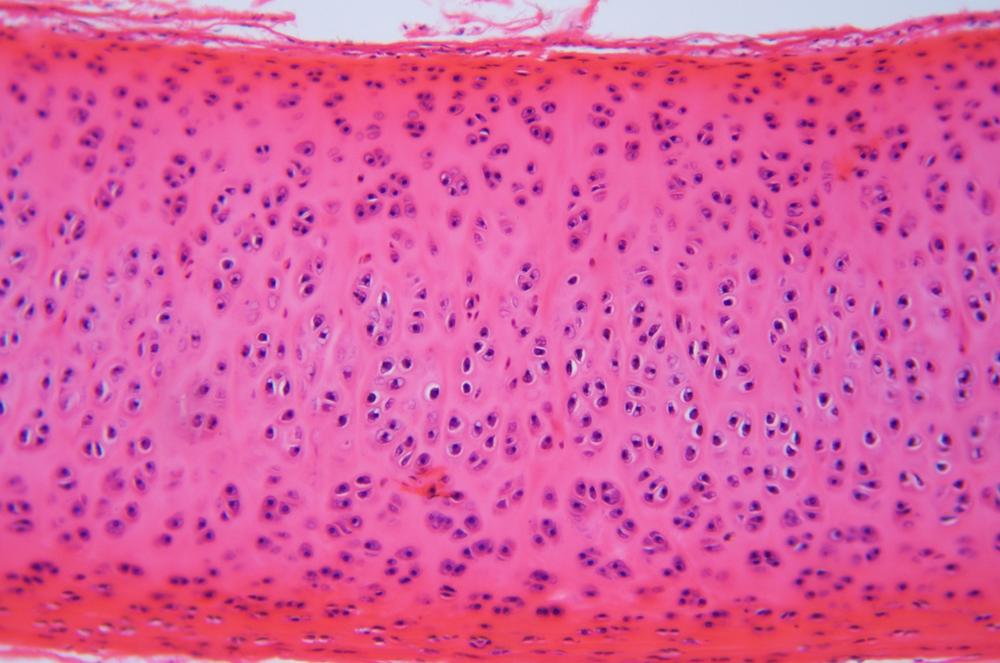

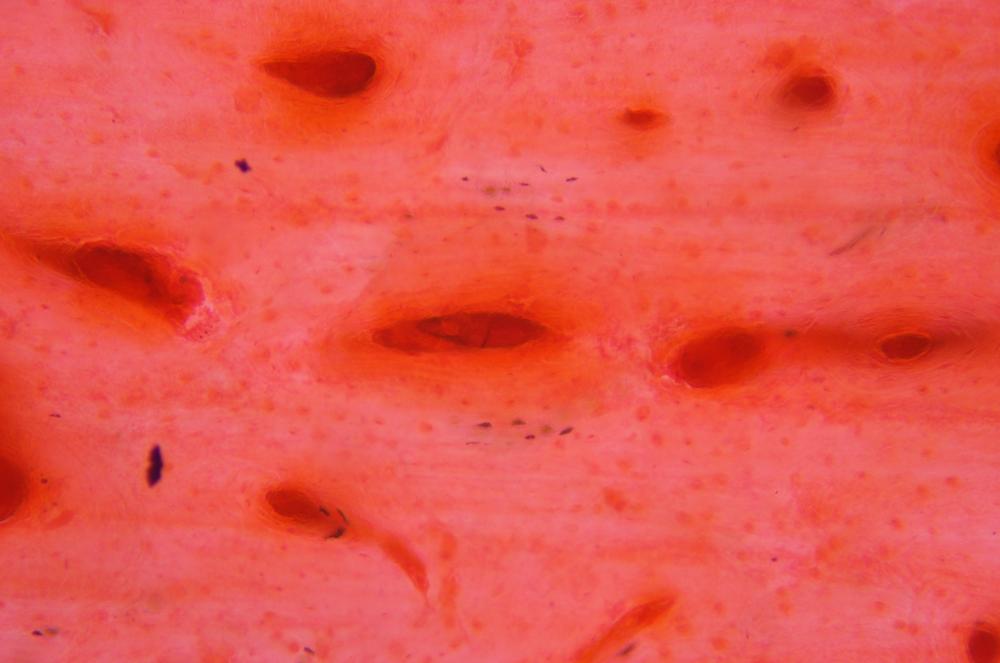

Cartilage is a semi-rigid special CT that is softer and more flexible than bone and harder and less flexible than muscle. Cartilage comprises cells called chondrocytes embedded in cavities called lacunae in an extracellular matrix of collagen fibers suspended in a gelatinous material called chondrin.

There are two subtypes of cartilage. Hyaline cartilage is the harder and more rigid, and is found as “padding” between the bearing surfaces where two bones would otherwise come into direct contact. Elastic cartilage is softer and more flexible, and is found in structures such as the larynx, external ear, and nose.

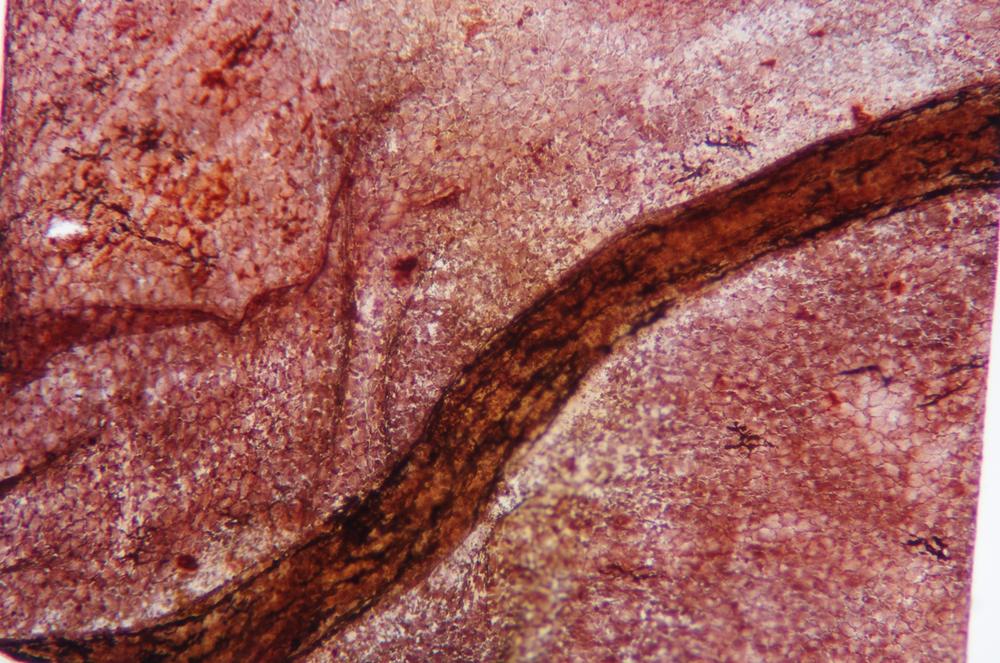

Examine prepared slides of cartilage in whole-mount as well as sections of hyaline and flexible cartilage. Figure 36-36 through Figure 36-38 show examples.

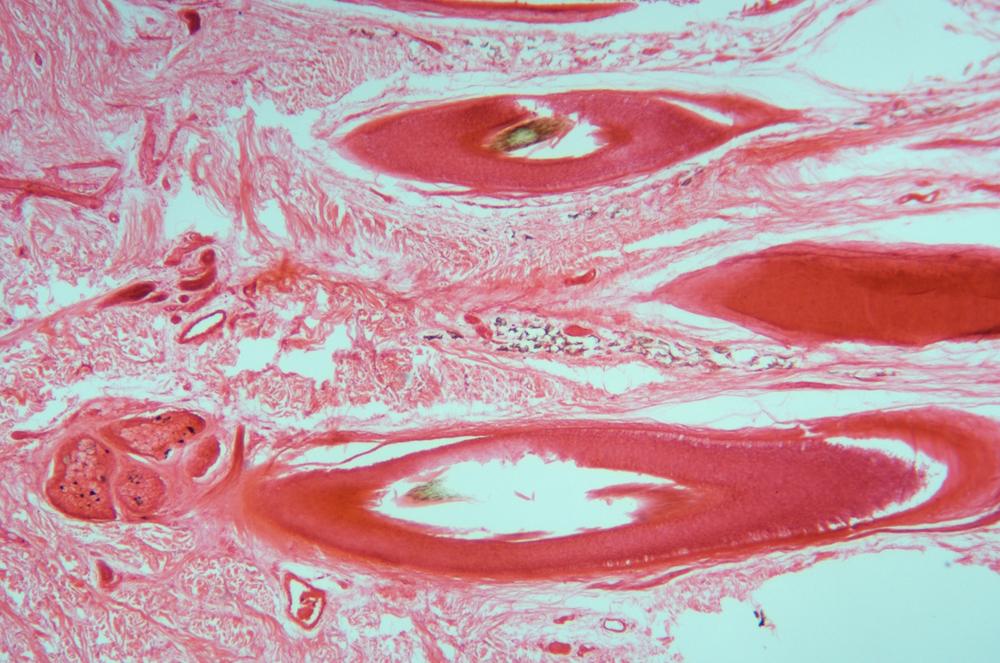

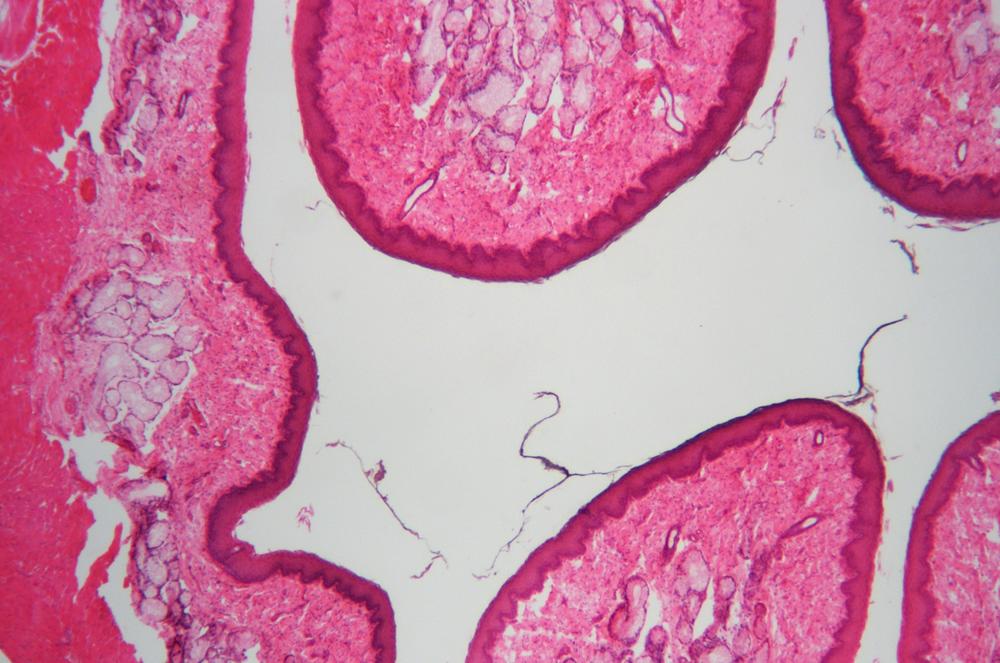

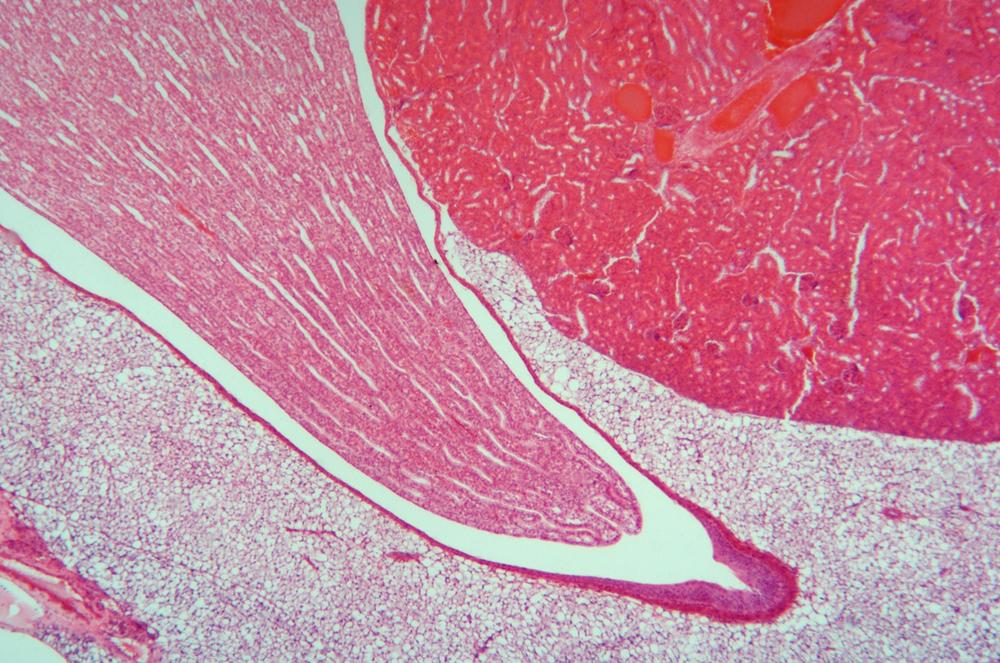

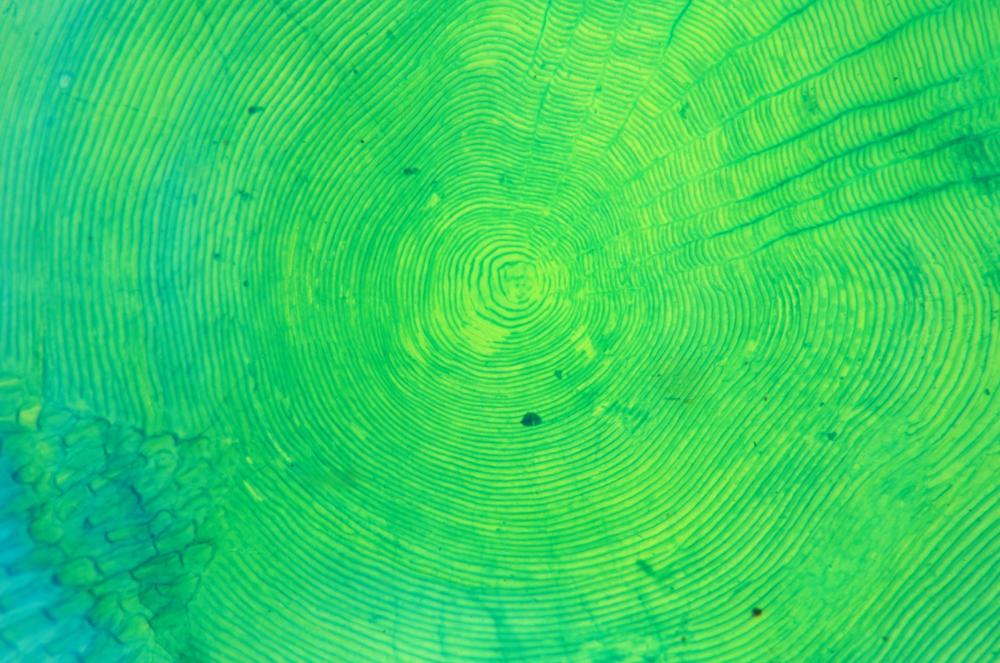

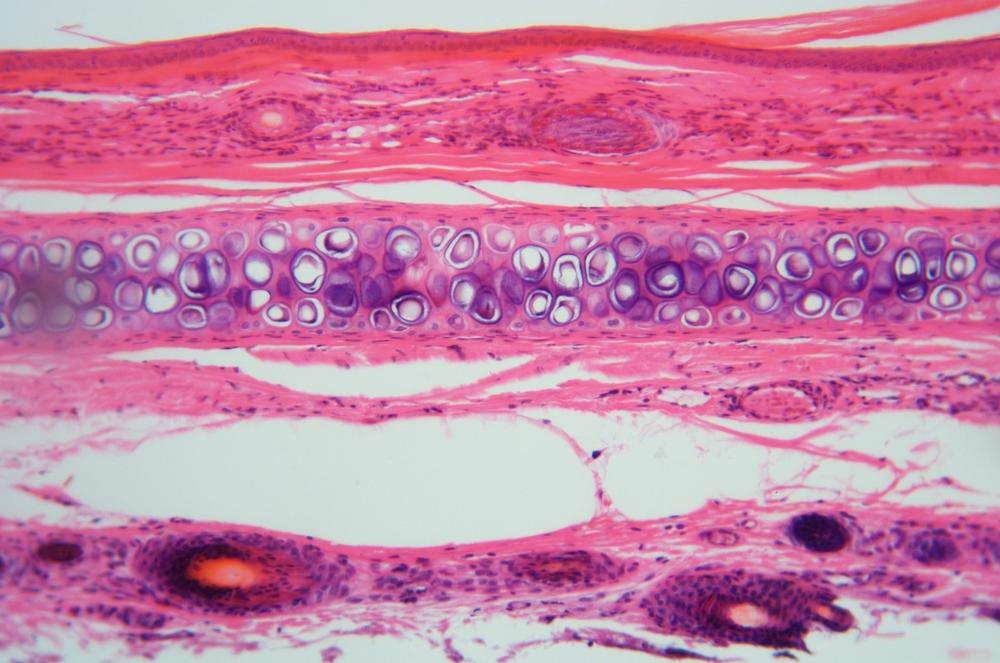

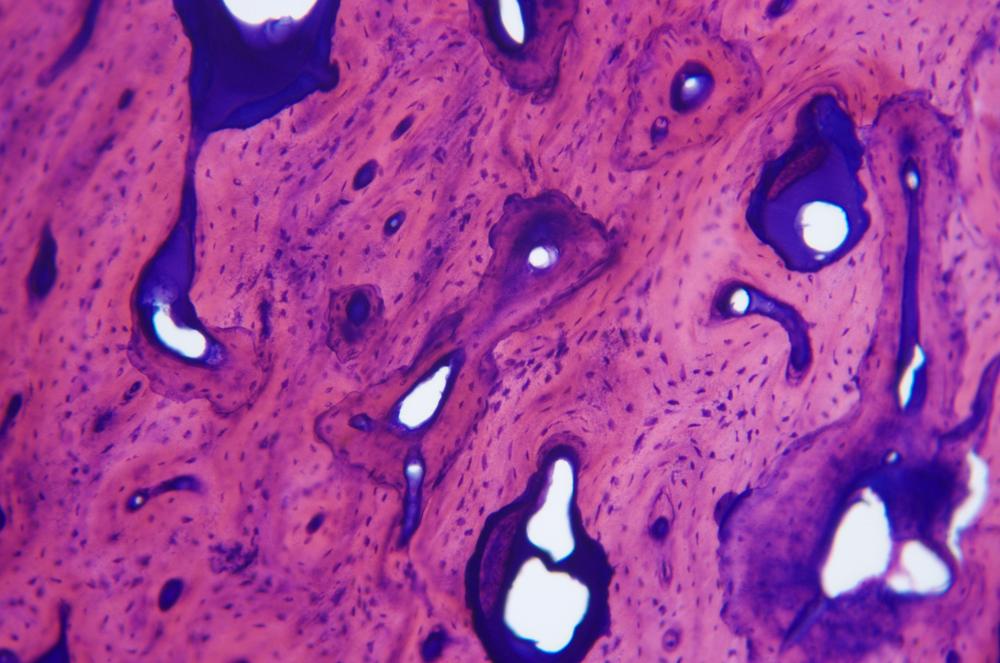

Bone is made up of bone cells called osteocytes embedded in lacunae in the extracellular matrix. The hardness and rigidity of bone relative to cartilage results from the composition of that matrix. In cartilage, the matrix is made up of collagen fibers suspended in chondrin, a gel-like material. In bone, the matrix is made up of collagen fibers suspended in an extremely hard and stiff substrate called bone mineral, which is made up of crystalline calcium salts that geologists call hydroxyapatite. Yep, a rock. (Well, technically, a mineral.)

Compact bone (also called cortical bone, hard bone, or dense bone) is extremely dense, strong and rigid, and forms the hard shell of bones. Spongy bone (also called trabecular bone or cancellous bone) is much less dense and relatively weak, and forms parts of the interior of bones, protected by compact bone.

Bone grows by forming lamellae, which are thin, concentric layers that resemble the growth rings of trees. Lamellae form around an interconnected network of thin longitudinal channels called Halversian canals, with the lamellae forming protective sheaths around the blood vessels and nerves that run through the Halversian canals.

Examine prepared slides of whole-mount and section slides of compact bone and spongy bone. Figure 36-39 through Figure 36-43 show examples.

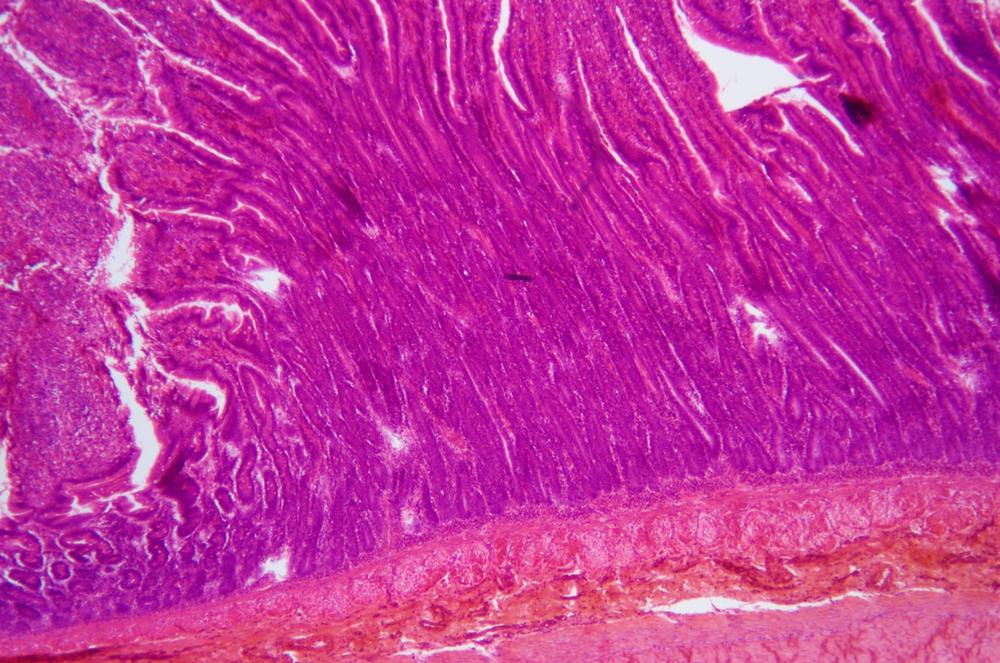

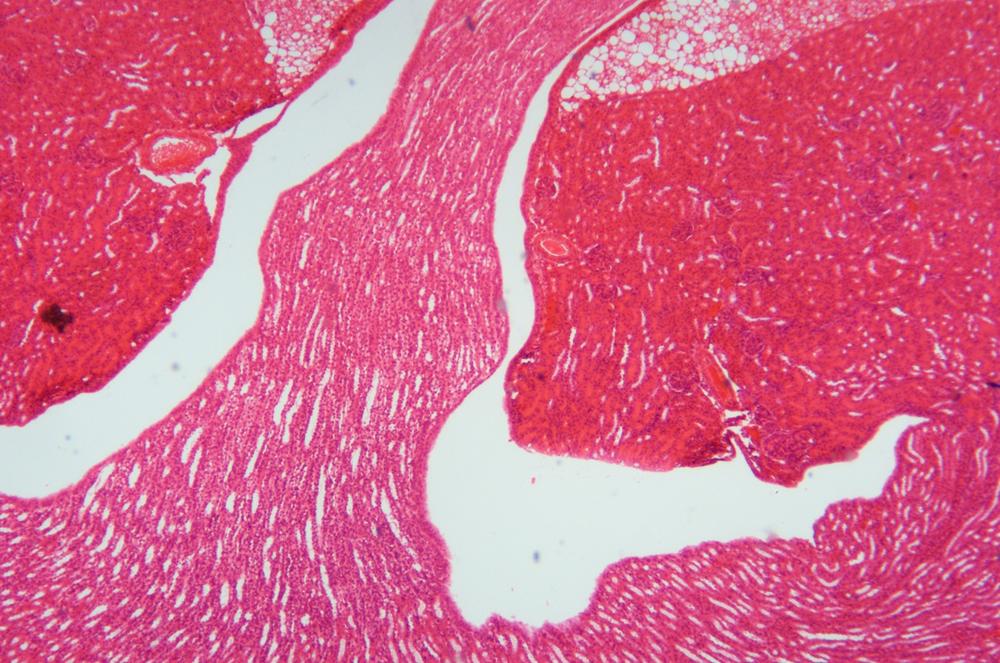

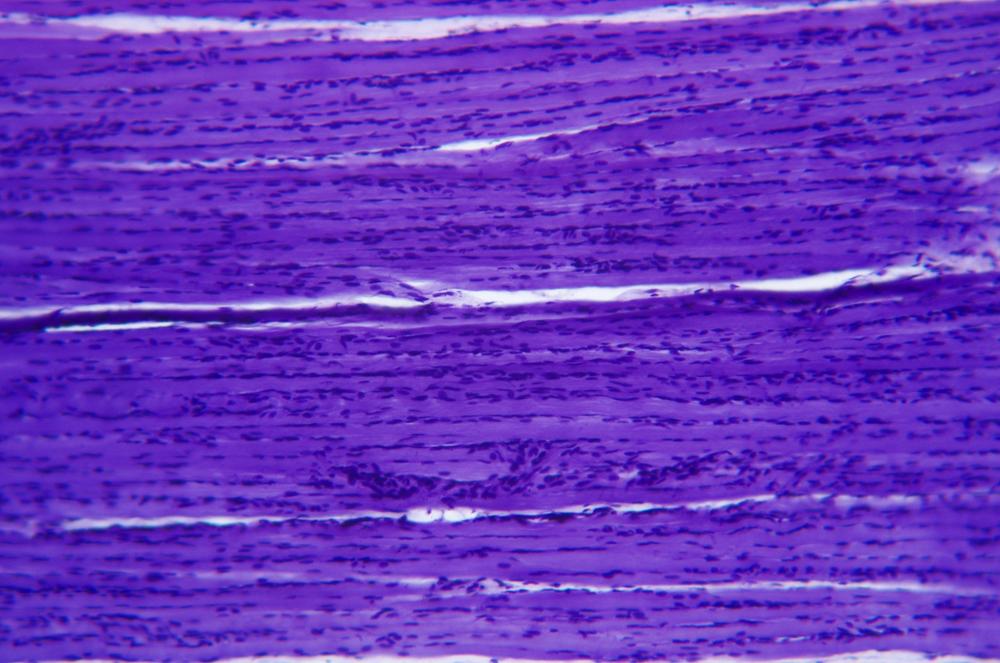

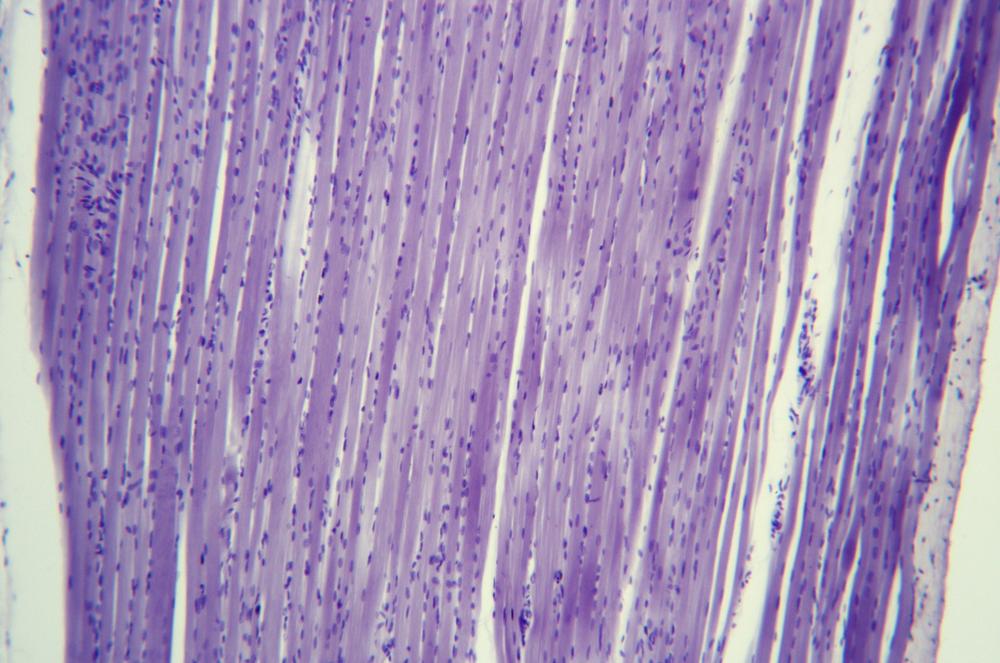

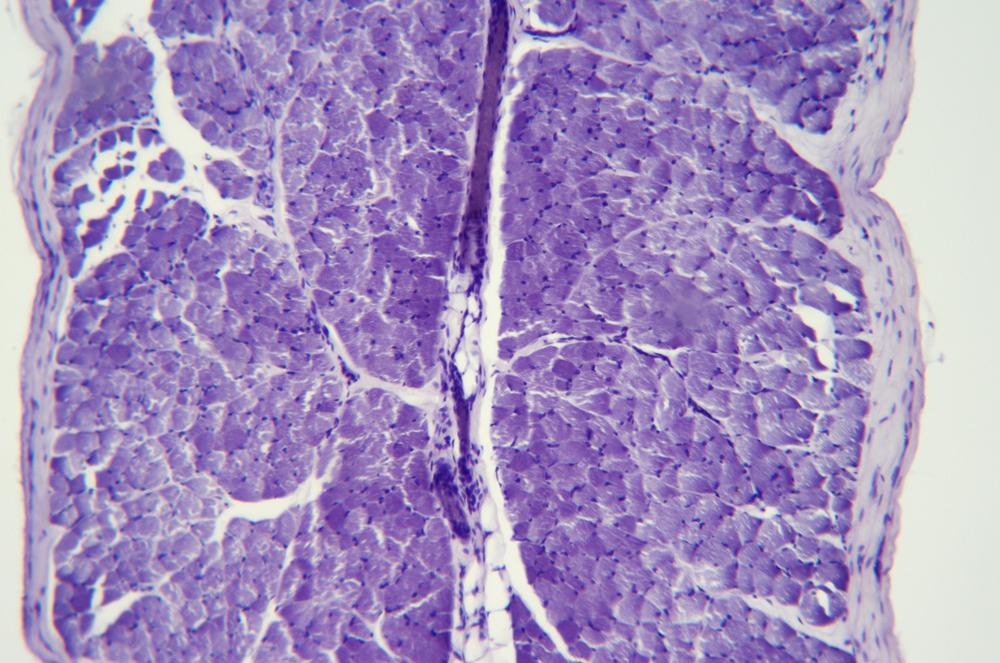

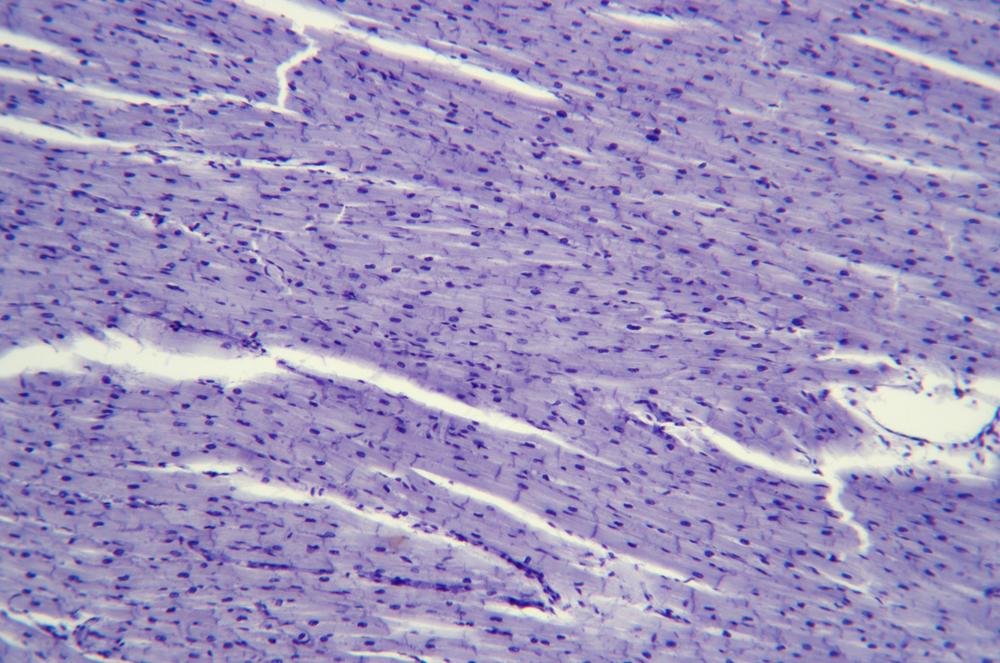

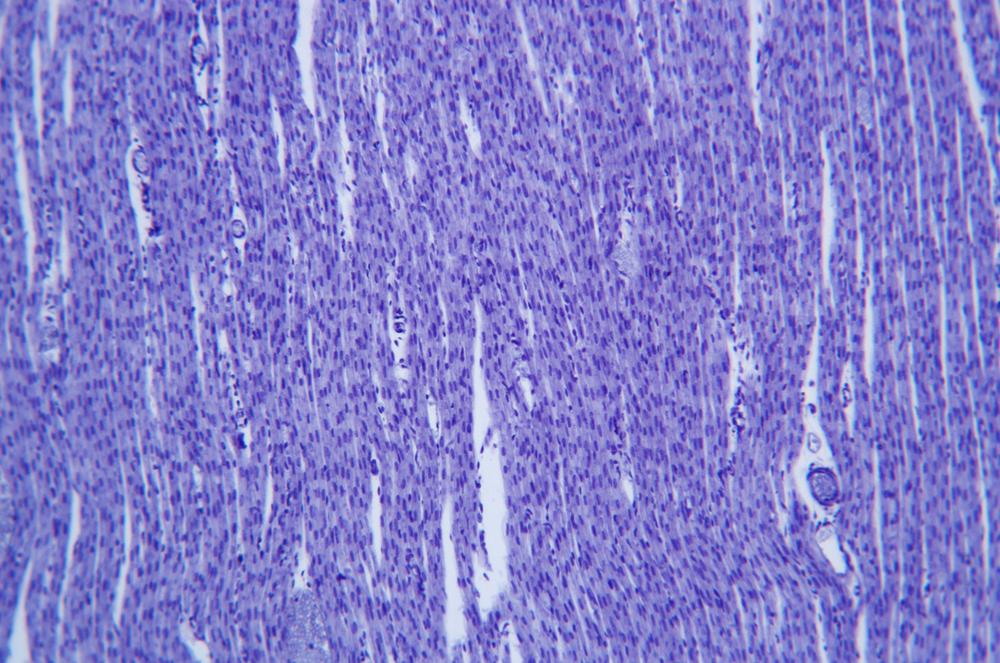

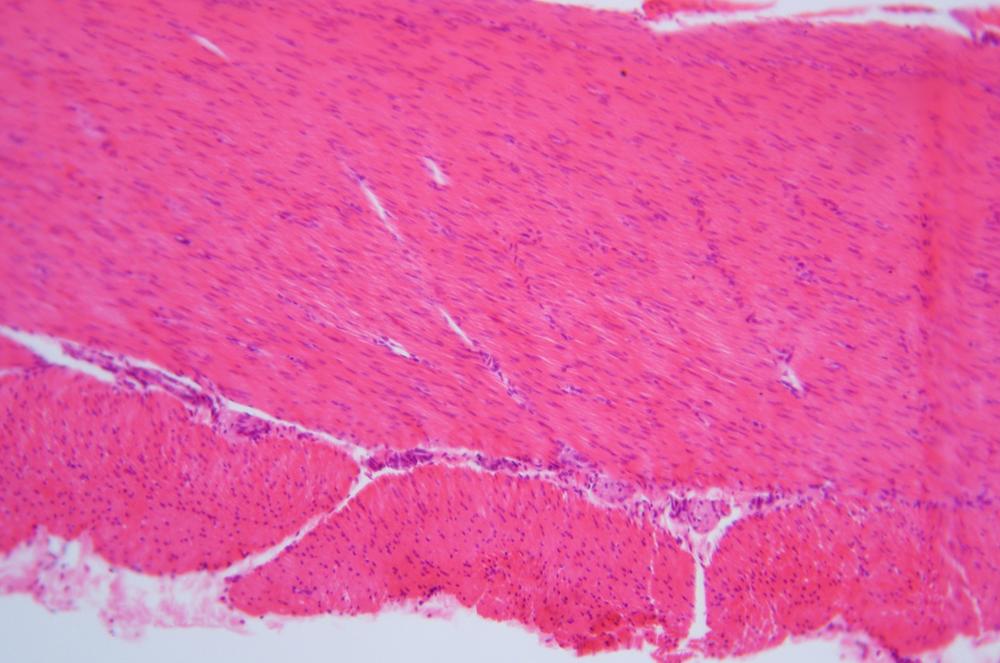

Procedure XI-4-3: Observing Muscle Tissues

The defining characteristic of muscle tissue is that it is able to contract and relax. There are three types of muscle tissue:

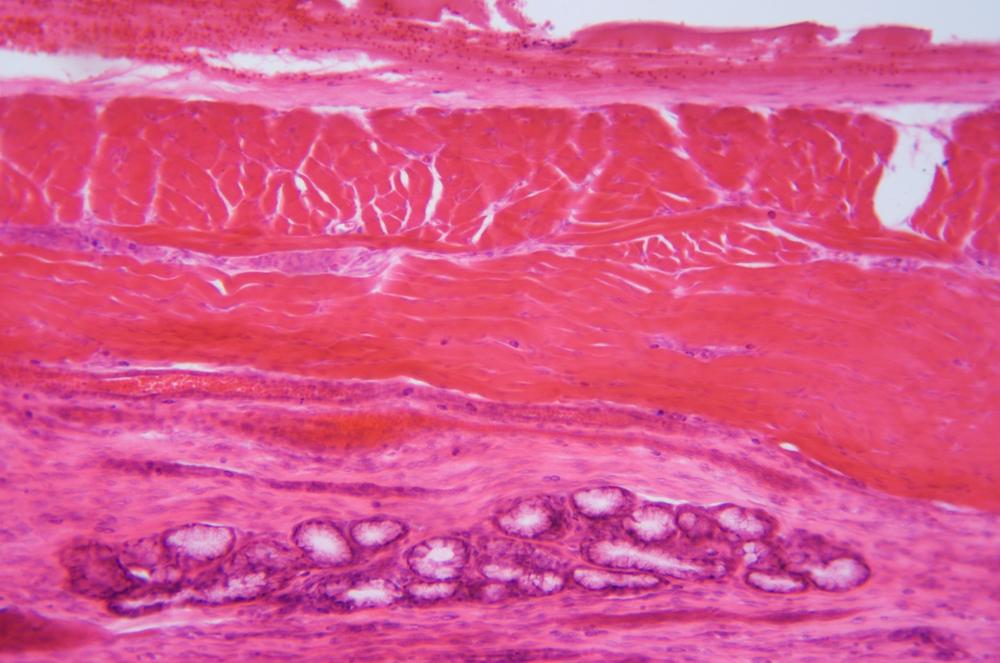

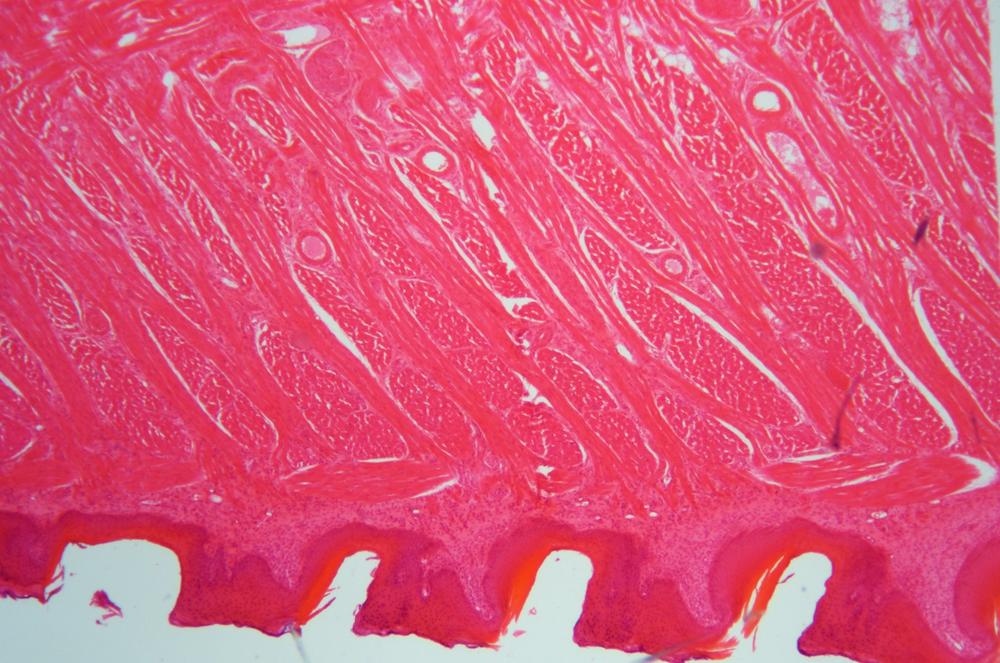

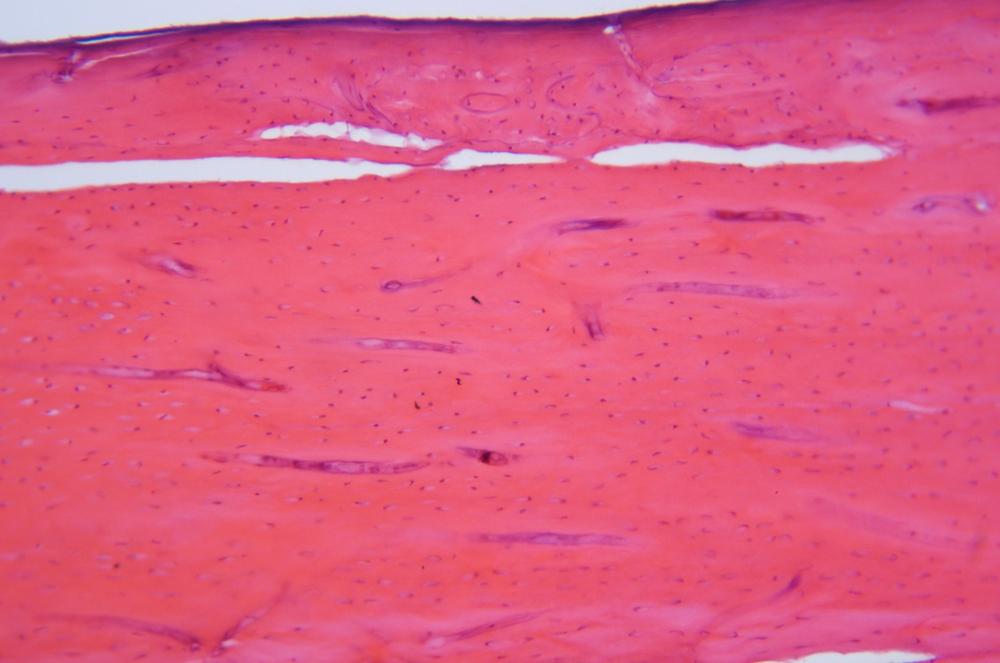

Skeletal muscle tissue, also called voluntary muscle tissue, is under conscious control, and powers all voluntary movements of the organism. Skeletal muscles range in size and power from the tiny muscles used to control movement of the eyes to the large, powerful muscles of the legs and buttocks. Skeletal muscles connect to bones via tendons, which anchor the muscle to the bone. Contractile cells in voluntary muscles are organized in regular parallel bundles, an arrangement called striated muscle. Smooth muscle tissue is made up of tubular muscle cells called myofibers or myocytes, which contain bundles of contractile filaments called myofibrils, which in turn are made up of chains of sarcomeres, the basic building block of striated muscle cells.

Cardiac muscle tissue, found only in the heart, is very similar in structure and appearance to skeletal muscle tissue, with the primary difference that cardiac muscles are not under the voluntary control of the organism. Contractile cells in cardiac muscles are striated like those of skeletal muscles, although the arrangement of contractile cells in cardiac muscle is a branching network rather than the parallel arrangement in skeletal muscles.

Smooth muscle tissue, also called involuntary muscle tissue, is not under conscious control. Unlike striated muscles, which are adapted for contracting intensely for short periods, smooth muscle is adapted to contract with much less power, but over very long periods. Smooth muscle is found within the walls of internal organs, where it performs such functions as dilation and contraction of blood vessels, peristalsis, and so on.

Examine prepared slides of whole-mount and section slides of skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle tissues. Figure 36-44 through Figure 36-51 show examples.

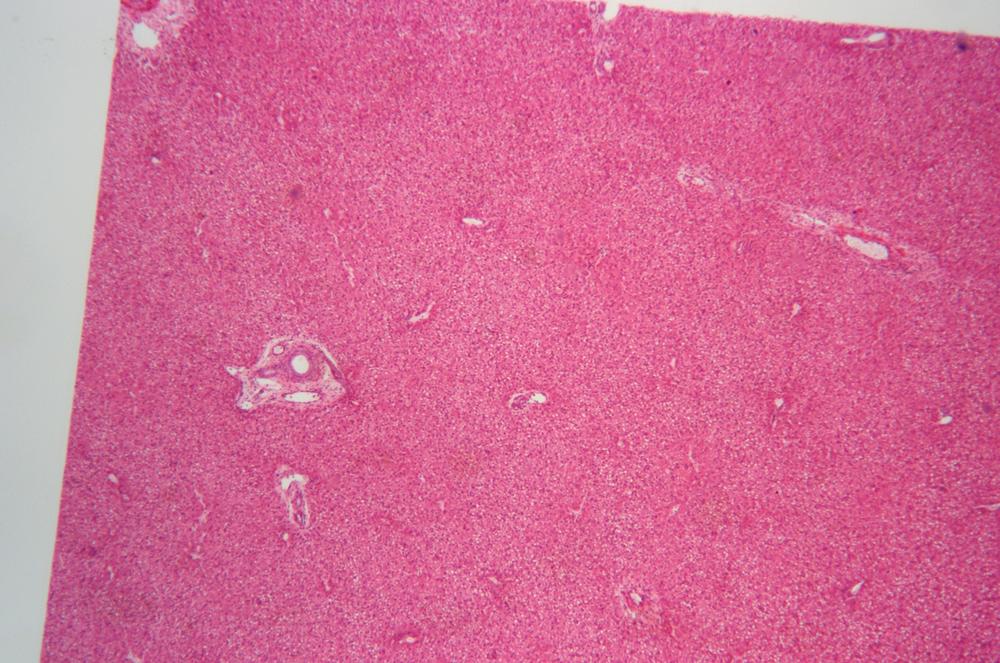

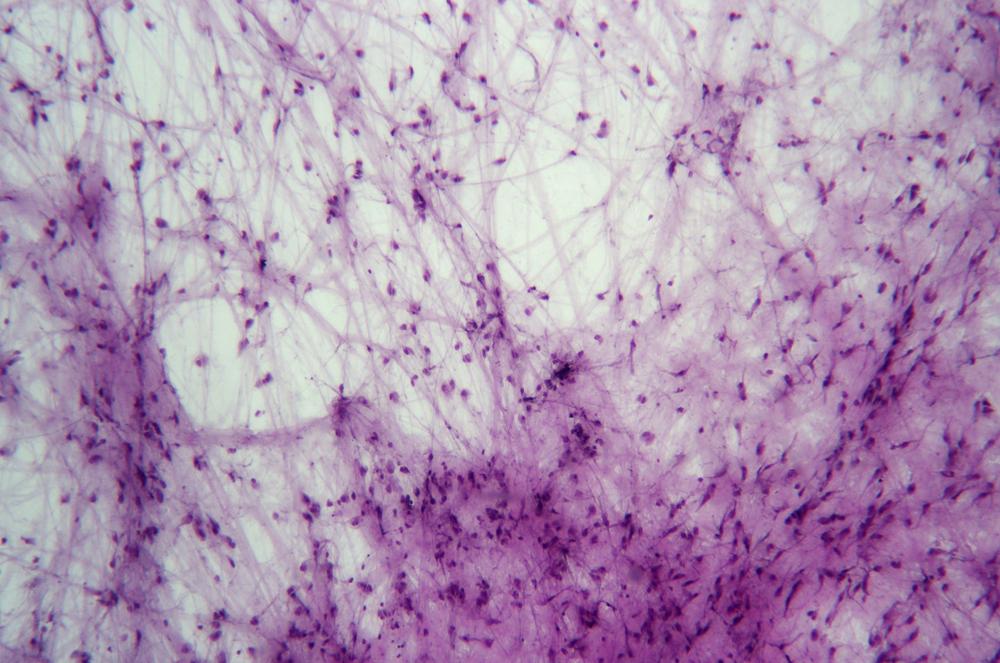

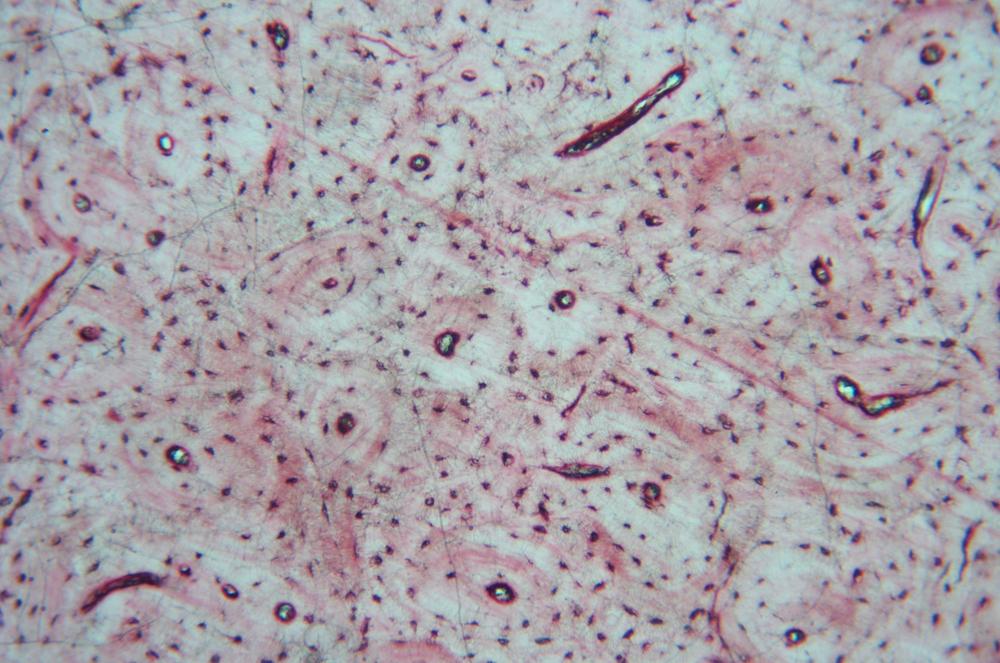

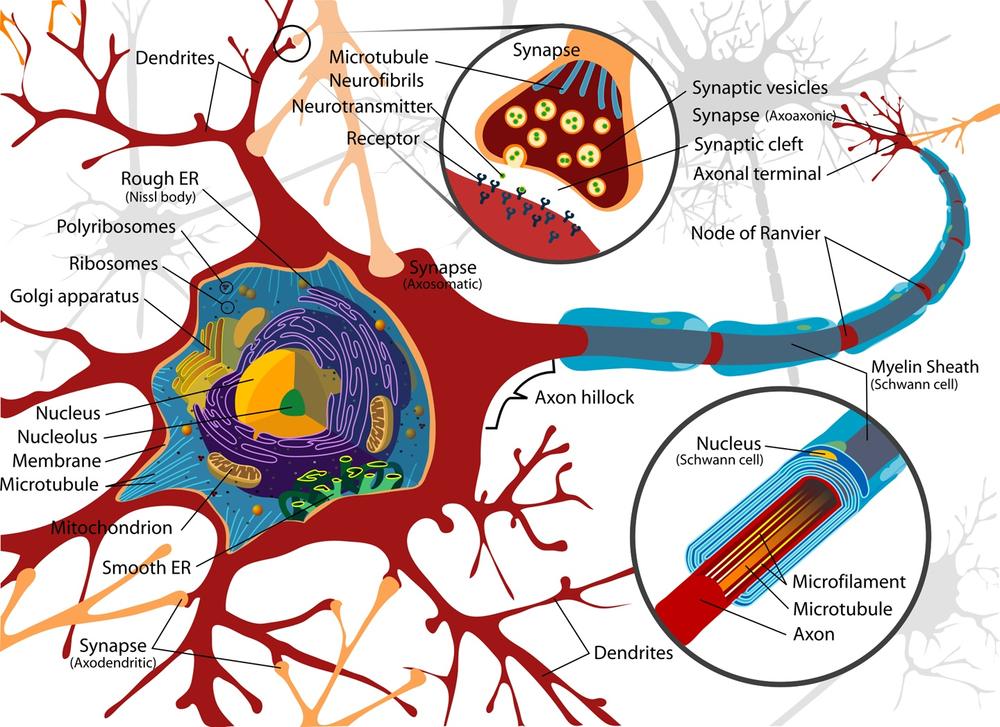

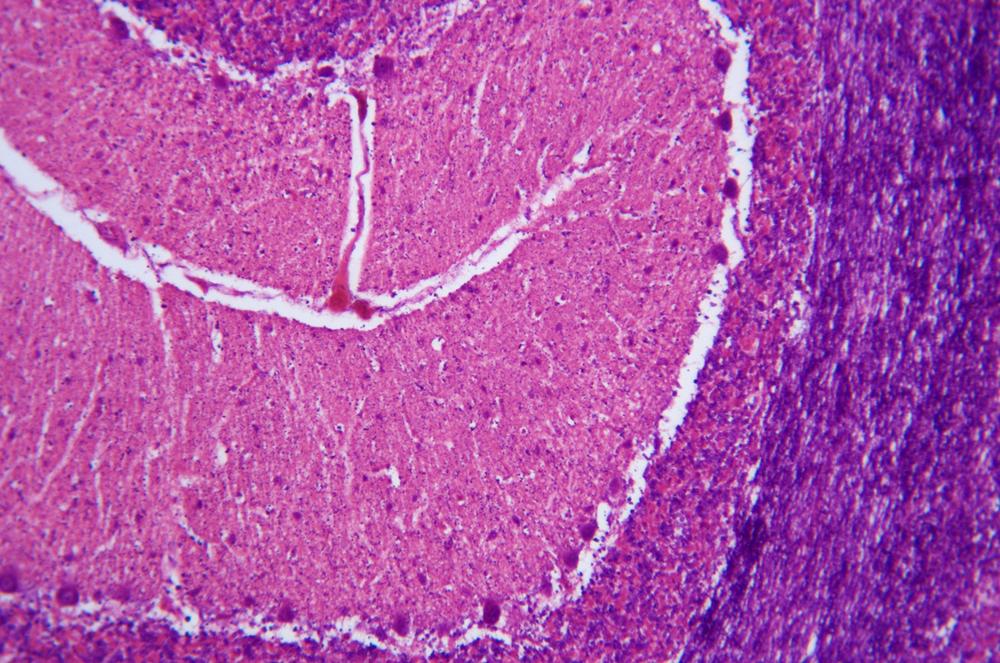

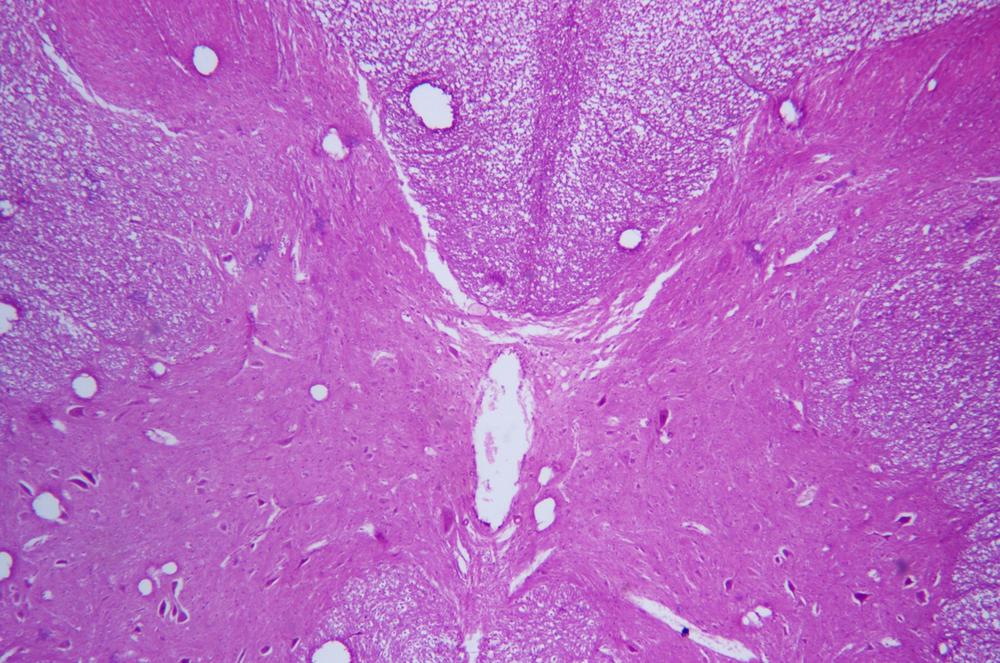

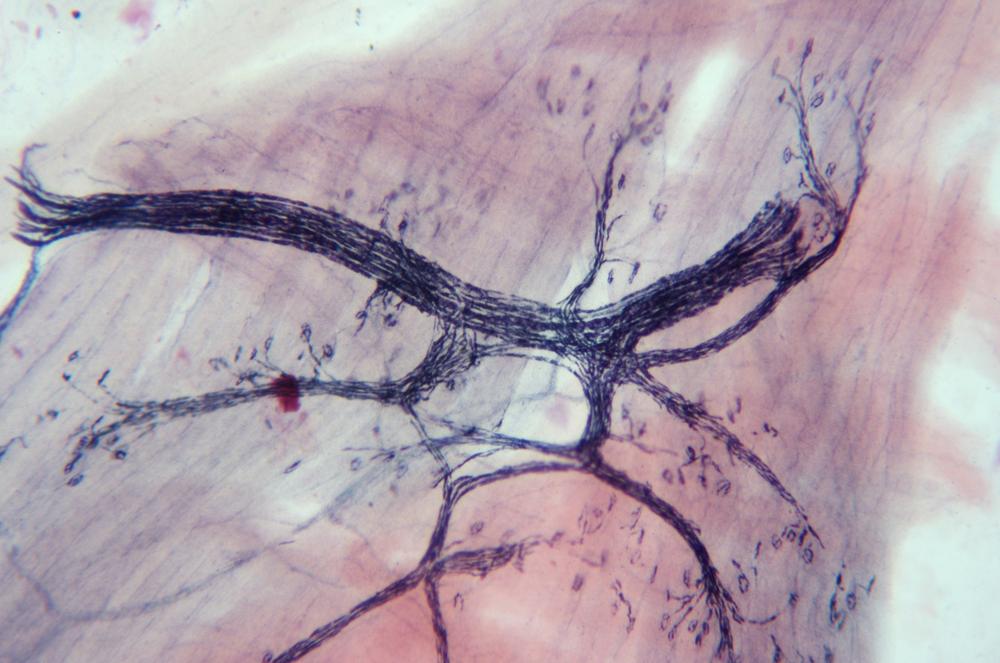

Procedure XI-4-4: Observing Nervous Tissues

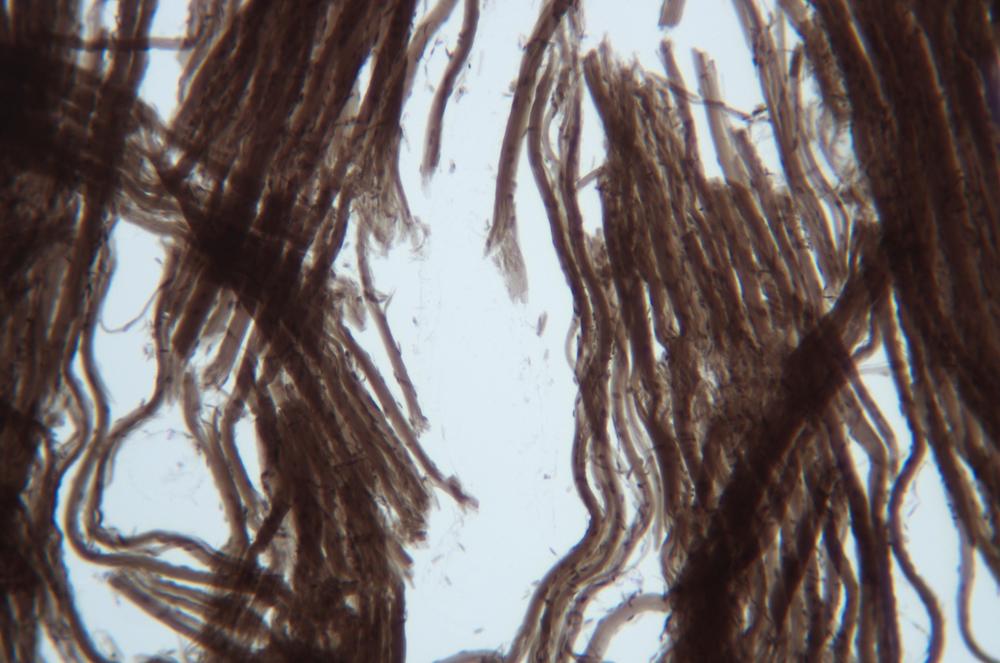

The nervous system—the brain, spinal cord, and nerves—is made up of nervous tissue. Nervous tissue is made up of large, complex cell groups called neurons, which transmit nerve impulses, and supporting cells—including astrocytes, Schwann cells, and other neuroglia cells—that support and work in conjunction with the neurons. Figure 36-52 shows a neuron and its associated structures.

In addition to the cell body, neurons have two types of cytoplasmic extensions that transmit impulses. A dendrite is a short extension that normally carries inbound impulses to the cell body from nearby cells and axons. An axon is a long extension that normally carries impulses from the cell body to remote dendrites and cells.

Nerves, found in the peripheral nervous system, are groups of neuron cell fibers (peripheral axons without cell bodies) bound by loose connective tissue called the endoneurium, surrounded by a sheath of dense connective tissue called the epineurium. Neural pathways, which occur in the central nervous system, are made up of bundles of neurons (including cell bodies) surrounded by myelin sheathes, and connect distant parts of the central nervous system with each other.

Examine prepared slides of whole-mount and section slides of nervous tissues. Figure 36-53 through Figure 36-55 show examples.

Review Questions

Q1: How can you discriminate visually between stratified epithelium and pseudostratified epithelium? Why might a stratified epithelium appear pseudostratified in a sectioned slide?

Q2: In sections, which types of epithelial cells resemble fried eggs, squares, and thin rectangles, respectively?

Q3: What difference characterizes mammalian erythrocytes from the erythrocytes of other vertebrates?

Q4: Of the four major components of human blood—plasma, erythrocytes, leukocytes, and platelets—which, if any, are not properly classified as cells? Why?

Q5: How can you distinguish mature erythrocytes produced by mammals from those produced by other vertebrates?

Q6: What purposes do leukocytes and platelets serve?

Q7: What difference did you note in the sections of hyaline and flexible cartilage?

Q8: What similarities and differences exist between the extracellular matrices of cartilage and bone?

Q9: Which types of muscle tissue are classified as involuntary? As striated?

Q10: How do striated muscle tissue and smooth muscle tissue differ in terms of power and endurance?