We were all in the parade

THE TASTE of our triumph was most enjoyed in the Communist Party. Our cell was the pride of Twelfth Street. The men downtown were convinced that we were close to taking over the Group Theatre; now to go all the way! As we were being congratulated, we were being urged on. The Proletariat Thunderbolt was invited to sit across the desk from the cultural commissar of the American Party, Comrade V. J. Jerome, and have a talk.

After suitable congratulations, we came to the subject of future policy. V.J. (initials! initials!) knew how history had moved in other situations at other times. It was the classic revolutionary instant, he declared, and not to be allowed to slip by. The actors had forced this great success on the Group’s directors; they should now take command of the theatre. The slogan for the moment was the classic: “All power to the people.”

It was my task to deliver Comrade Jerome’s instructions (suggestions? no, instructions) to the cell. But before I did, I wanted to talk over my position with someone I trusted. I couldn’t with Harold Clurman for obvious reasons, so I turned to the other person whose point of view and principles I respected, my wife, Molly. Despite being drama editor of New Theatre magazine, Molly was a person independent of dogma. Marx teaches: “Doubt everything.” I’d never felt that the comrades doubted anything; they knew what they thought and what they thought was what they’d been told to think. Molly, a Yankee, was brought up, if not to doubt everything, to question everything. She sure as hell questioned the ability of the actors of the Group to run their organization. The thought made her hoot.

Molly had been an instructor at the Theatre Union and had experience with politically “correct” amateurs throwing their ideological weight around in an artistic organization. She’d been through the Theatre of Action experience with me. She’d been witness to the spanking the Party had given Jack Lawson and his humiliating retreat from his personal artistic intention. “Crawling to the feet of V. J. Jerome,” she’d called it. “What the hell does Jerome know about the operation of a theatre?” she’d asked. Had he ever been backstage? Jack, having regretted his choice of the hero of Gentle Woman and expressed his contrition at length, moved to Hollywood, where, converted and rewarded, he was running the Party’s show. Ranks marching left were not to be broken.

I carried Comrade Jerome’s message back to our regular Tuesday night meeting in Joe Bromberg’s dressing room, passed on his instruction that our cell should immediately work to transform the Group into a collective, a theatre run by its actors. It was a surprise to me when the members of our cell quickly and unanimously did what the Theatre of Action people had done in the matter of the La Guardia play—give in to the political directive from the man on Twelfth Street. Then it was my turn to speak. I was timid; despite my present reputation as a bullheaded man, up until that time breaking ranks was an act of boldness for me. I surprised everyone by my recalcitrance; I surprised myself. I believe I sounded apologetic for disagreeing. I could feel bewilderment and impatience around me. I suppose the position I took was a sign of disrespect for my fellow actors’ political savvy. And possibly their courage. They voted me down.

Later I found out that they blamed Molly and the influence of Harold Clurman. They saw that I was on the side of the directors, not the “people.” Therefore I was undemocratic. And therefore—how ironic!—not a good Communist. But what they blamed most was my character: I was an opportunist who’d do anything to get to the top. I’ve been accused of this many times by many people. The fact is that I do have—call it elitism—strong feelings that some people are smarter, more educated, more energetic, and altogether better qualified to lead than others. I also believed then and believe now that a person’s agreeing with me politically is not a guarantee of his or her artistic talent. I was not impressed with the arguments of my cellmates.

Evidently there’d been more discussion after the meeting in Joe Bromberg’s dressing room, because in time I was notified that another meeting was being called—but not by us. Apparently a decision had been made downtown, by someone higher up, that another gathering had to be convened to deal with our problem. This was not to be held in the Belasco Theatre dressing room but in the large, comfortable sitting room of one of our comrades, Mrs. Paula Strasberg. (Her husband, Lee, had agreed to take in a movie that night.) I was told where to go and I knew that what would take place there would be top-level, decisive, and final. I tried to prepare my position—but I wasn’t prepared for the form the meeting took. Or who’d be there in charge.

Try to remember as you read what follows that this decisive meeting was held in an apartment above Sutter’s Bakery, where they used to make the best cookies in Greenwich Village. They were baking that night, and all through the meeting the most delicious fragrances—caramel, cinnamon, and rich melting chocolate—rose from below and filled the room.

The morning after the meeting, I wrote a long note for myself, an account of the events of the night before. I knew it was a turning point for me, and I didn’t want to forget the details of what had happened. I’ve edited what I wrote forty-eight years ago but not rewritten it. I gave it a title back then: “The Man from Detroit.”

As soon as I walked into the Strasbergs’ sitting room, I saw it was going to be a policy-setting meeting. The old flopping around in the minds of friends was not going to take place, not that night. True to the process of democratic centralism, the “line” was to be set not by the membership but by a “Leading Comrade.” I was never introduced to the man, and I have no idea what his name is. There were a few other new faces in the room, who had about them a kind of “revolutionary” glamour [in those days, anyone who wasn’t in the theatre seemed glamorous to us. They were “really in life,” so we actors thought]. The principal speaker was an organizer in the Auto Workers Union, his headquarters Detroit. There was the strongest possible suggestion in the introduction that brought him on that we were damned lucky to have this man there with us; he’d set us straight. We’d gone slightly screwy—“the way artists have a tendency,” the comrade said. (Everyone simpered at this.) So “we needed a little straightening out,” he said.

Now Democratic Centralism got down to work. [Democratic Centralism is a process whereby one of the men from the “hard core,” a “Leading Comrade,” lays down the true dope and everybody thinks it over and says, “I agree.” Then they all go home and do what he said. Only people as full of self-doubt as actors could go for it quite the way our bunch did. The memory embarrasses me.]

The Man from Detroit spoke forcefully. And, surprisingly, all about me. He analyzed me. Although he’d never seen me before that meeting, he understood me perfectly. He’d met many others like me in his work, he said. I was the foreman type. I was trying to curry favor with the bosses; I wanted to join hands with the exploiters of the working class. (The “bosses” in the group were drawing fifty dollars that week.) He underscored my errors. If the man had met me on the street the next morning, he would not have recognized me, but that night he had, if no details, a wealth of theory. I was typical, he proclaimed. He had a very strong face.

I sniffed the smell of pastry from below and looked around. The rest of the boys and girls in the room were sitting there dutifully bewildered. There is an expression children get when they confront a problem too big for them, a problem that they are happy to leave to their elders—a look part dazed, part just plain waiting. There’d been an awful lot of very long meetings. Everybody was tired of them.

Suddenly the Man from Detroit got more direct. He spoke directly to me, urging me to straighten myself out. (Apparently all was not lost.) He heaped scorn on me in a nice, theoretical fashion. A door opened in the back and the husband of the comrade whose apartment this was (Lee) inserted a sleepy face past the edge of the door. Everybody sprang to life and shooed him away. The door closed on us and on me. I wished I were outside. My fellow members, shaken out of their fixed rapture, now looked at me for an instant, before turning their attention back to the speaker from Detroit. Their look now was kindly and forgiving. There are few pleasanter feelings to experience than granting forgiveness. I was going to be forgiven! I could rely on that. But first I had to eat a little more of the well-known black bird. The leading comrade was pouring it on. My God! I thought. This man never saw me before half an hour ago. He’s got some damned nerve! And how can these people sit here and look at me that way? I began to hate that kindly look of tolerance for my errors that shone on everyone’s face. I longed for the cold, clean winter air outside.

The Man from Detroit was coming to the end of his speech. I could tell because the end was the classic holding-the-door-open-for-the-return-of-the-transgressor. Yes, the door was being held wide open for me to walk back into favor, except that to judge by the cow eyes of my pitying friends, I was expected to make that walk back on my knees. I wasn’t listening anymore. I wanted to get the hell out. [I was a sinewy young man and I was beginning to think about how many of these guys I could beat up. That, of course, was irrelevant.]

A vote was taken. I’ve forgotten exactly how the issue was put. I doubt that I heard it. It amounted to: How many against me? All except one. How many for me? My hand went up. I was for myself. A big step.

Outside, it was cold. The bakers, as I walked by, were working late. The streets of Greenwich Village were empty. At home, before going to bed, I wrote a letter, resigning from the Party.

I understood an awful lot about future events from that meeting, and all I needed to know about how the Communist Party of the United States worked. The Man from Detroit had been sent to stop the most dangerous thing the Party had to cope with: people thinking for themselves. There’d been some “discussion” after he got through. Comrades took the floor and competed as to who could say “Me too” best. They all did a grand job. The fact was that there was no appeal from the verdict of the Man from Detroit, so no discussion was necessary. I understood the police state from him; I know what I’m reading about when I see the words “authoritarian rule.” The man was not only stopping people from thinking; he was setting up a ritual of submission for me to act out. He wasn’t even operating out of a conviction of his own—he, too, was there on orders. He’d been sent to us with a hatchet, one he’d used before. Despite the grace of chocolate-covered cookies and sweet hot tea, the meeting was strictly strong-arm stuff. He’d come to make us all frightened, submissive, and unquestioning. The assumption of human cowardice on which he operated was so profoundly insulting that it didn’t penetrate totally until years later. By then I was another man.

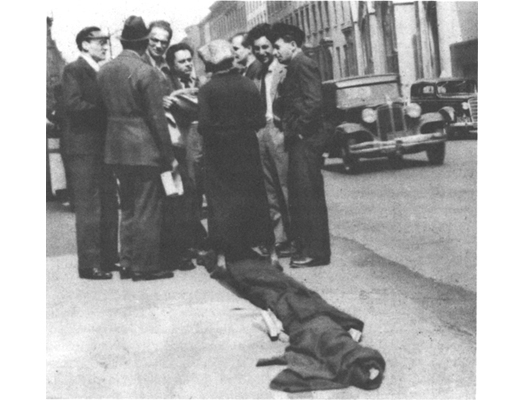

THEN came a surprise. Despite my resignation, which was in no way equivocal, my relations with my old comrades did not change. The Theatre of Action people must have known of my withdrawal, they must have talked about me, but I continued as their training leader, without loss of respect or devotion. A few months later, on the first of May, I walked with my old Group comrades in that year’s May Day demonstration. Look at the snapshot; there is the most congenial harmony among us. How happy and at ease I look! I was glad to be out and glad to still be in. For this year’s parade, a united-front affair, we built a large triangular frame over which black cloth was stretched. At regular intervals holes were cut, through which we poked our heads. Each of us wore the headdress of a different worker—coal miner, steelworker, longshoreman, baker, cook, and I, of course, wore my taxi driver’s cap. That May Day was a lively and happy celebration, and although I never again had anything to do with the Communist Party, I was as devoutly sympathetic as ever to the worldwide movement for the liberation of the oppressed and happy to march with the others to affirm this.

What did my former comrades think of me that spring? I was not told, but at a guess I’d say they considered me confused but useful. The harmony I enjoyed was a tactic; it was to pass.

I had an even bigger surprise. There is an old Greek myth of a demigod or human (I’ve forgotten which) who puts on a mask to disguise who he is, then after some time decides to take it off but isn’t able to; the mask won’t come off. So it was with me. It took me many years, as you will see, to pull that mask off.

In other words, I continued to think like a Communist. The theatre is a weapon. A play must teach a lesson. The third-act climax must send the audience home with hope and courage born of a sweeping revolutionary insight. Only I and those like me had the answers. I continued to regard the society around me as hostile and repressive, yes, corrupt beyond redemption by peaceful change. Why? Because it was run by moneymen. Change is necessary; in fact, inevitable. What kind of change? Complete. Final. A shift of power. Trust the working class. Only. Defend the U.S.S.R. With all its faults. (This did change.) My duty as a theatre artist was to teach others the right way and lead them down the right path.

All of us who came out of the “movement” and all those who remained in the “movement” were marked with this intellectual arrogance. We were sure of our “positions,” and it was too damned bad for anyone who didn’t agree with us. We were sure we were right. After I resigned, I did not think any differently than I did when I was a member. In fact, I still believe a good part of what I believed then.

The answer to why Party members didn’t change toward me for a time is simple. These were the years when the Party’s program was the Popular Front. The sole criterion in political matters was: What is most useful for the survival of the U.S.S.R.? More clearly than America’s leaders, the Party saw the onrush of Hitler and World War II. Of course, they were much more threatened. Determined to make the broadest possible front of alliances to counter the coming threat, they wanted everyone in any way “useful,” even someone as insignificant as I was, on their side. And they were determined that in the coming crisis the U.S.A. should be with them. The slogan they raised was: “Communism is twentieth-century Americanism.”

Some people bought it. For a time I made that mistake, confusing the philosophy of this country with that of the CP. But against the Party’s simulated democracy and tactical patriotism, there stood the man with the thrust chin and tilted cigarette holder. Behind FDR was the American tradition of individual independence. Behind that, the Constitution. What FDR said by every act and every posture, in every speech, was: “This society can be made to work. Our people are good. Our problems can be solved—our way. Democracy must be preserved. We’ll overcome all obstacles.” He didn’t have to say any of this; he embodied it.

His presidency was the time in my years when, as a nation, we had unity, belief in the future, laughter, fearlessness, intelligence, energy, and even some love for each other. It was during his reign that I began to break my old Anatolian mold, through FDR and MDT—my wife Molly, another intrepid, stubborn individualist. It was during FDR’s years that I began to see that I could be one of the people here, not against them. The spirit of the thirties rescued me from my roots.

THE YEAR after Awake and Sing! I was playing in Clifford’s next play, Paradise Lost. It had not been enthusiastically reviewed, and we were all on cuts. One week I drew down eighteen dollars, another twelve dollars, and since Molly and I were having a child, I had to look around for supplementary income. I began to work as an actor on radio “hours,” shows like Gangbusters, Crime Doctor, The Ed Sullivan Show, and, for Orson Welles, a thing called The Shadow, of which he was the star. I remember him arriving for rehearsal one morning; he’d been up all night carousing but looked little the worse for it and was full of a continuing excitement. A valet-secretary met him at the side of the stage with a small valise containing fresh linen and the toilet articles he needed. The rehearsal was never interrupted—Orson had unflagging energy and recuperative powers at that time—and he soon looked as good as new. There was no swagger of aesthetic guilt there; The Shadow was not patronized, only slightly kidded, and this affectionately. The cast were “his people”—many of them turned up in Citizen Kane later—and they knew their business, so that week’s installment was soon done and well done. It was a way of making a good living in a bad time and no disgrace, especially in light of Orson’s plans for the Mercury Theatre and the films he was preparing to make. Seldom have I been near a man so abundantly talented or one with a greater zest for life.

Half a century later, I’d left films and theatre and was writing novels. I’d never been close to Welles personally and lost track of where he was and what he’d been doing, informed only by the usual column rumors. One weekend I was in Beverly Hills to go on talk shows and help peddle my latest novel. My publisher had provided me with a limo to take me quickly—I had a tight schedule—from one show to the next. I was assigned a driver who turned out to be an aspiring writer. He’d once carried Welles from his hotel to the studio where he was making a commercial, had observed Orson carefully, and described him to me with a writer’s appreciation of detail.

He said that Orson had become so heavy that he couldn’t squeeze through the passenger door into the back of his limo but had to be wedged through the front door and set down next to the driver. Welles was holding a brown deli bag, and once they were on a thruway, he opened it, pulled out a roasted chicken, and began to tear the meat off a thighbone with his teeth. Piece by piece, he consumed the bird, breathing hard as he did, then he fell asleep. The driver had to wake him at the TV station and help him out of the car and into the studio where Welles was going to speak for a wine company. “Is he trying to kill himself?” the driver asked.

I made a point of catching the commercial. Orson offered the nation his assurance of the product’s worth with a voice as resonant as ever—a beautiful instrument indeed—and his presence was, in some grotesque way, still imposing. I couldn’t help wondering—as I do with any sponsoring of a product where an artist is paid to say what he’s paid to say—did Orson, himself, believe what he professed? Of course, he must be broke, so he has to earn his living this way. What a tragedy, to put such a talent to this use.

I contrasted this puffy huckster with the dauntless, spirited fellow I’d worked with in the thirties. I remarked how he dressed now, entirely in black, a formless, unbound costume, the kind of garment old women choose to conceal the infirmities of an aging body. I thought of what he was wearing as a great tent inside which he was hiding. I also thought of him—remembering his glory years—as a great beached whale, driven onshore by a storm or, more likely, by some mysterious turbulence in its essence. Why this slow suicide among whales? No one has ever found out. Was there some compulsion of shame or spiritual defect here that made Orson “let himself go,” then degrade his huge gifts by making commercials? Did he have an impulse, like the one that beached the whales, to rush to the end?

Some months later, when I heard him speak in Central Park at an anti-nuke rally, seated in a wheelchair on a platform to which he’d been raised by a forklift, he still said the old brave things and enjoyed the acclaim a favored celebrity receives. Yet I thought his defiant, antiestablishment declarations sounded hollow.

When I think of large talents that were beached by a crisis in their lives, I think first of Clifford Odets. There is one sorrow that must pain men so stranded most: that they were unable to live up to the image of themselves that once gave them their pride. Clifford was what Orson was not, a celebrated member of the Communist Party. In 1935, after his first two plays hit New York, he was the artist-revolutionary of the day, honored and respected by all good men. In 1952, he did what I’d done, named the Party members in the Group to the House Committee on Un-American Activities, and whereas that act, unhappy as it was, gave me an identity I could carry, naming his old comrades deprived Odets of the heroic identity he needed most. I don’t believe he was ever again the same man.

I remember that a few weeks after his testimony, he, Molly, and I were walking down Lexington Avenue one evening, when we were accosted by a group of young people, decent and well educated they were, who began to jibe at Clifford, telling him how disappointed they were in him, how he wasn’t what they’d believed him to be, and how badly he’d let them down. Clifford didn’t defend himself; he was silent. The encounter did not last long, and we were soon continuing down the avenue. He still wasn’t speaking, and there was nothing I could say or Molly wanted to say. I’ve been glad ever since that I did what I did, had regrets that some old friends had been hurt but none about hurting myself. Clifford, though, was distressed not because of hurting other people but because he’d killed the self he valued most.

Eighteen years later, during the decade when I could make any film I chose and Clifford was beached in Hollywood, I’d go west from time to time to speak with the studio heads who were providing me with production money, and the first personal friend I’d call was Clifford. “Come, I’ll take you to dinner,” I’d say. “Lets go to Chasen’s.” But he wouldn’t, not ever, not once. Finally I stopped asking him out; I could see that the reasons that made him refuse were painful. He wouldn’t go to the “in” restaurant in the film colony because he’d have to pass tables where people would ask, “What are you doing now?” and he’d have to either lie or say, “Nothing.” Or he’d encounter liberals who’d look at him, then look away as he passed. The fact was that the only jobs he could get at that time were rewrites, patch-ups, and dialogue fresheners, which he’d have trouble admitting; but what would have pained him more were the snubs. So he’d answer me, “Let’s stay here. I have some sirloin. I’ll make us a pair of fine steaks, and we’ll talk over old times.” Which is what we did. His house was dark and quiet, and in an eerie way I saw that he was on an alien shore and that he was a beached whale.

There are others whom the waves of thought and art in the forties, when they retreated, left stranded. Brando, like Welles neurotically overweight, and by some mysterious choice out of things, respecting no one and least of all his own profession and his incomparable gifts, hides on a dirt hill over the film colony or in Tahiti. There are others too, many of whom make fat livings by boosting commercial enterprises—you’ve seen them on TV. These men in their private moments still present themselves as rebels—like old actors coming back again and again to play a favorite role, the one in which they scored their great successes. But in their hearts, I believe, they know the unhappy truth, that they are now deep in the system they once loathed and attacked. Many of them are affluent, with a Mercedes or the assurance of a stretch limo and an obedient chauffeur at their command. They are all good men, men of the “movement,” as it was called, not the Communist movement but the surge of hope and confidence and determination that took over from the Great Depression, the anti-monopoly-capital movement, the common-man movement, the anti-colonialist movement of the thirties and forties. These were and are worthy causes, causes with which I am in sympathy, and, as much as the others, I hold on to the postures of those days and the dreams we once all had. But now, in the cold light of a cold morning, those dreams are troubled when they exist at all, and on the beach lie the remains of that other time.

There are a few out of that experience whom I’ve watched with less sympathy. I have a photograph of an ad Lillian Hellman made for a fur company. When she was asked how she came to give herself to a commercial display so crass, she replied that they’d “caught her on a bad afternoon.” The interesting part of the photo is not the drape of the mink (her compensation), but the cock of her hand holding a cigarette in stock glamour-girl pose, and her face, which I read as saying, “I’m not so damned unattractive, am I now? I’m right in there with Mercouri and Streisand and even Bacall! Don’t you think?”

I can sympathize with that but less with another recollection, one she does not record in her memoirs, of the days at the end of World War II when she’d bundle with Russia’s ambassador, Maxim Litvinov, under his limousine’s lap robe at the same time that her fellow Jews were dying by the hundreds of thousands in Maxim’s master’s labor camps. The story goes that during this time, Litvinov and his wife, Ivy, came home one night from a pro-United Front affair and as they prepared for bed, Max asked Ivy, “Don’t these liberals here have any idea of what’s going on in our country?” Lillian did know—hell, we all knew, and some even thought it justified—but Lillian was silent. She didn’t remain beached, however, but spent her last days on the high seas, flapping her tail and spouting high!

All these people struggle to hold on to an integrity they feel does not exist now and a hope that died. Not having found a new life they were able to respect, they do their best, under circumstances that are difficult, to maintain what they once had and believed in. Above all, perhaps, they strive desperately to go down as themselves, to at least finish in their own style. Artists of talent, they fought and fight still to continue in their proudest identities. The talent they lack is a talent for facing certain painful truths. This is no shame. What they believed in, long ago, was not a fact, it was not substantial; it was a dream and no way less worthy because of that, but—

Los sueños sueños son.