Struggling—my first Hollywood film

I INTERRUPT my narrative to tell about the character of Samuel Goldwyn (Goldfish), the producer; without his knowing it, he was to affect the course of my life. Goldwyn was one of the breed who swarmed into southern California during the twenties and thirties, the men who created what’s called Hollywood. With one exception, I knew them all: Louis B. Mayer and his muscleman Eddie Mannix, B. P. Schulberg, the Warner brothers, Darryl Zanuck, Spyros Skouras, Harry Cohn, David Selznick, Samuel Goldwyn, and the lesser men who consorted with these marvelous monsters and used them for models. They were all men of unflagging energy of a size that’s no longer about, with the possible exception of Rupert Murdoch, the Australian publisher. “Tycoon” is too tame a word to suggest the quality of the men I’m recalling; that is why I’ve left out the more cultured Irving Thalberg. I’m talking about a gold rush, about desperate men in a bare-knuckle scramble over rugged terrain, roughnecks thinly disguised, men out of a book by Frank Norris or Theodore Dreiser, alike in reach and taste, occasional companions in social intercourse but, when they felt they had to, ready to go for each other’s throats.

In the prime of their energy, these men were impatient to get to their offices every morning, rather like a champion fighter pushing down the aisle of a crowded sports arena, hungry to get to the ring and beat hell out of a challenger. Despite a few bad scenes, I admired them for their manic intensity and their vanity. Yes, vanity. With them it was a creative force. They competed with each other in the most wholehearted and uninhibited fashion to see who’d make the best picture of the year, who’d pile up the biggest grosses, who’d sign up the most important new star, director, writer. Making movies was their life; nothing else mattered.

Samuel Goldwyn was a proud man, proud of his productions with good reason, but also proud of himself: his figure, his bearing, his appearance, and his physical vitality. At sixty-three—when he had Constance under contract—he made a practice of walking from his home to his office every morning, followed closely by his chauffeur and car, ready to pick him up if he puffed. He must have been aware that people were observing and admiring him. “Oh, he does that every morning. Yes, he’s quite a man, Mr. Goldwyn.” Provided with the best suitings and haberdashery, carefully turned out by a devoted valet, he made an admirable figure. Sam wanted to look like Samuel Goldwyn.

Constance didn’t know how lucky she was. Sam did not make a “program” of films every year, as did Harry Cohn and Darryl Zanuck, the Warners and Louis Mayer. He made films one at a time and was interested only in the best, employed the finest screenwriters, only the top stars, and, whenever he could, the man who was for him the best director of that day, Willy Wyler. As was the case with his contemporaries, the extraordinary energy of this man was sexually rooted, and he, no less than the others, had from time to time to assure himself of his continuing potency, but he did not scramble around his desk, chasing starlets over whom he had the hire/fire power. Here, too, he went only for the best.

They tell of Madeleine Carroll sitting on Sam’s office sofa one day, cool, poised, and very British. For a onetime glove salesman out of New York City, she must have been an irresistible attraction. He managed to get on top of her, but this lady was out of a sophisticated culture and had considerable experience dealing with rampant males out of control. With a clever twist of her body, she dislodged Sam from her belly and threw him on the floor. As he “adjusted” his clothing, Sam drew himself up into his most dignified posture and, speaking in his characteristic sibilant purr, proclaimed, “I have never been so insulted in my life!”

Sam was proud, as was all this generation of producers, of the talent he discovered. Apparently he believed that Constance had what it took to make a star, for he was seriously considering testing her for the leading role opposite Danny Kaye in Up in Arms. The question is why he was so impressed with Constance, who had very little acting experience. Since all these men thought of every film they made, no matter how serious the theme, as a love story, they made a practice of casting by a simple rule: Does the actress arouse me? Or will the actor awake desire in the women in an audience? When it came to judging a new actor’s sex appeal, Darryl Zanuck would call in his wife, Virginia; he thought highly of her judgment and candor. Or he’d gather secretaries who were sure of their jobs and would speak their “truth.” He might also be influenced by what was known as the actor’s “track record.” But when it came to actresses, not Darryl, not Harry Cohn, not Louis Mayer, not Sam Goldwyn needed consultation. They went by a simple rule and a useful one: Do I want to fuck her?

I believe this rule of casting is not only inevitable but correct, and quite the best method for the kind of films they made. The audience must be interested in a film’s people in this elemental way. If not, something essential is missing. If the producer wasn’t interested in an actress this way, he was convinced an audience wouldn’t be and that this actress wouldn’t “draw flies.”

There was a more general aspect to this casting practice. Since many of these men who became the great producers evolved out of the very bottom of the middle class and were not blessed by birth with what might make them easily gain the favors of attractive women, and furthermore, since many of them were Jews and felt in some way “outside” the goyish upper-class society with which their films dealt, they were particularly drawn to blondes and to “proper” ladies (Grace Kelly). The unspoken, unwritten drama would consist of bringing these immaculate-appearing women (Deborah Kerr) down to earth (or the sea’s surf), where the rest of us wallowed and sinned. Sam Spiegel preferred his leading ladies to be long-legged, small-breasted, “coltish” Anglos. Gentleman’s Agreement had Dorothy McGuire, and Julie Garfield, a street kid in type, was given a scene telling her off. Hitchcock favored ladies who looked standoffish (Madeleine Carroll, Tippi Hedren, Grace Kelly) and pure (Ingrid Bergman), no matter what the facts of their personal lives. The film’s action would consist of getting these women into trouble and bringing them down into the “muck” that is humanity.

There was another attractive image of women that these old fellows liked: the sassy girl, the ones advertising men today call “provocatives.” Sam Goldwyn repeatedly told Constance that he was going to make her into another Carole Lombard, and she believed him. This kind of woman, by challenging the opposite sex, aroused in men a desire to subdue and dominate. Sam saw this possibility in Constance, and he believed it an elemental, basic quality she was born with. It certainly wasn’t acting talent he saw, because adorable as Constance was, she had little acting talent. But she was a hoyden, and Sam saw it.

Sam would sit her on his knee, she told me, and give her instructions as to how she should behave. How? Like a star. Above the rest of womankind. He edged her away from certain friends, encouraged others. He advised secrecy in all personal matters. He introduced her to his confidential coterie, which social contacts were, in effect, auditions. Sam would call his friends the very next morning and ask what they’d thought of her. She was always on view and on trial. It happened that most of his friends found her charming, but some, wiser and more experienced, responded with: “I’d like to see some footage on her first.”

Sam was telling her how to dress, walk, and make up. He was critical of her street makeup, favored as little as possible, wiped it off himself. He cautioned her not to say too much, ever. “They can’t fault you for what you didn’t say,” was his idea. He believed mystery an important star element. Garbo! I didn’t believe this was Constance’s style, but he had her ear and her trust, worked to create an intimate and dependent relationship, made her feel free to come to him at any time for advice and think of him as a kind of daddy—a rather lecherous one, to be sure.

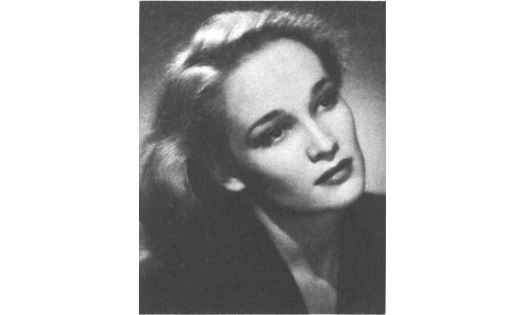

Constance (Photo Credits 15.2)

He’d instructed his press department to begin gathering material on her, photographs in all poses, dressed and undressed, as well as all kinds of stories, true or imagined, and have the material at hand so that when “it” happened, they were ready!

When it came to her tests, and there were several, he gave her “everything”—the best cameraman, the best wardrobe (he bought her four new outfits for the street, all a little overwhelming, I thought, but I was not in the business of making stars)—and assigned the man who was to direct the film, Elliott Nugent, to direct her tests. She was flattered to death by his interest and concern.

She told me that Goldwyn was eager to meet me and took me into his office herself; I suppose she was showing me how “in” she was with him. But it was so; they were very cozy. He told me he was going to make a star of her. I’d met Sam several years before, when I tested for his Dead End. I reminded him, but I don’t think he even heard me. He couldn’t think of anything except the film at hand. His energy and optimism got to me; he had me believing she was going to make it!

She would be at the studio all day, rehearsing with Danny Kaye, whose film debut it was also to be. I was free but didn’t know what to do. As my interest in tennis wore out, I became restless and bored. There is nothing to do in southern California. At night she was edgy with hope and anxiety. I sympathized but began to feel that she might prefer to be without distraction during the big moments ahead. I told her I’d go back to New York for a bit—to see my kids, I said. She didn’t object. We’d been ecstatically happy.

IN NEW YORK, I found that Helen Hayes had been asking for me. She wanted some moments in the performance looked after. Nothing bores me more than picking up pieces, patching holes, and quieting backstage unrest. Without going to the Henry Miller, I went to our country place, to see how the new furnace was working. It was okay. I stayed on; it was my chance to be alone. When I got back to New York, I found that Helen, peeved by my show of indifference, had influenced Gilbert to stop paying me my fifty-dollar-a-week director’s royalty. Perhaps she thought this would bring me rushing back to the theatre. It was an act that called for an answer, but after complaining to Miller and being told that Helen was his whole show and he didn’t dare offend her, I said the hell with Harriet and didn’t bother with it anymore. I recalled Helen’s gratitude when I came in to take over rehearsals and the phrase “miracle man,” all forgotten for fifty dollars. It was a lesson—mostly for my lawyer.

A CONFESSION. When the Soviets made their pact with Hitler, in August of 1939, my feelings were ambivalent. I understood the pact as an effort by the U.S.S.R. to protect its western border by turning Hitler in the other direction. This alliance, I told myself, is what a war of survival makes necessary. That was also the line of Communists everywhere. Despite resigning in disgust from the Party four years earlier, I still had protective feelings about Russia; the indoctrination endured. What I’d been against in 1935, I told myself, was specifically the American Party and its meddling in the theatre. The Soviet Union, after all, was the one place on earth where socialism was being attempted. A nation that had produced the films and theatre I admired had to have a sound core. And there was this: Since the Russian Revolution in 1917, the “Capitalist Camp” (there’s a good old CP phrase!) had tried in every way to destroy the U.S.S.R.

That this loyalty had endured surprises me now. I do believe my reaction was more prevalent—secretly—than is generally supposed. What finally did turn me off was the flip-flop of the leading comrades two years later when Hitler turned his panzers east, invading Poland, then Russia itself. Many left-wing intellectuals vaulted shamelessly—in twenty-four hours—from considering the war imperialist to proclaiming it a war to save civilization, which it certainly was. I stood to the side of the great flood of pro-Soviet feeling that followed. That was the beginning of the end of my attachment to the U.S.S.R.

It was not until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor a few months later that I began to feel allegiance to our side in the war. I went to my draft board; they ruled me 4-F. When I wasn’t drafted, I persevered with my work in the theatre. Later, in California, I observed with amusement the studio heads, producers, and directors becoming “instant colonels.” They threw off their houndstooth sports coats, to be measured by expensive tailors for officers’ uniforms. In London they moved into the Connaught and Claridge’s, both hotels well behind the lines. But John Huston and Darryl Zanuck did court danger, and I admired those of my friends who enlisted as privates and went where they were ordered. I particularly admired Jimmy Stewart, who took risks over Germany beyond anyone else’s. Meantime, I read the newspapers and followed the war from the sidelines, as I would a vast drama. In Hollywood the war was a great distance away; it was remote.

But when I returned to New York, I had contrary feelings. I felt ashamed and guilty as well as something else: I was missing out on the experience of my generation. As a filmmaker, could I afford that? Since I was still 4-F—I checked again—I tried to find another place for myself. I could speak Greek and Turkish, so it occurred to me I might have value in the Office of Strategic Services. I’d made a friend in California who was in the OSS, and I wrote asking that he propose me.

Meanwhile, I agreed to do a show in New York for the Department of Agriculture that would explain the importance of rationing to the public. I worked with Earl Robinson, an old associate from the left theatre, and with Arthur Arent, who’d been the main writer on the Living Newspaper. We cooked up lively direct-at-the-audience stunts, including one novelty where a woman on stage has an argument about rationing with her image on a motion picture screen. My old dance teacher, Helen Tamiris, represented a juicy steak in the movements of modern (aka revolutionary) dance. After we’d put it all together, the show was praised by Washington and, so I was told, played all over the country. I never heard of it again and have no idea if it was successful as a “Learning Play.” I do remember that I felt less shame afterward; I’d done a bit of my duty.

I heard from Constance that she had the role with Danny Kaye; I should “hustle my parts” out there. She came to meet me, looking prettier than ever and suddenly more grown-up. Later she drew a very hot bath for us to share, and perfumed it. I wondered where she’d learned about perfuming a bath. We went to the Beachcomber’s, our favorite haunt, to “recover,” lifted three “golds.” (A “gold” is a delicious, smooth, fragrant, sweet, tart, frothy rum drink.) The next day was Sunday, and we stayed in all day and talked, as she urgently wished, seriously. I represented no doubt to her about my divorce. Molly had asked for it, I said—which was true. I assured her that after one more stage show in New York, I intended to come west for good and make films—which was also the truth.

I was getting attractive offers to direct films; it was a matter of choosing. MGM wanted me on a term contract. Warner Brothers and their energetic, plump producer, Jerry Wald, had signed my friend Clifford Odets to prepare a screenplay from a story idea Jerry had; it was to be called An Errand for Uncle, a patriotic piece for wartime consumption. But it was an idea, not a script, and while I thought Jerry fun to be with, I also thought him a con artist; if I didn’t like one idea, he had another, often quite contradictory, on the tip of his tongue. Despite Clifford, I backed away. Abe Lastfogel had taken me to Fox, the “goyish” studio, to meet Louis D. Lighton, a producer, who was going to make a film of Betty Smith’s novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. I liked this man immediately. He spoke in a way I wasn’t accustomed to, from far over on the right, but he also spoke of feeling and capturing an emotion, of humans in stress and the ambivalence within people. He reminded me of a New England Yankee, a farmer perhaps, a tall, proud man with a flat belly that contrasted with the chummy lard around Jerry Wald’s middle. Actually, what Lighton did when he wasn’t producing pictures was to “run”6 cattle in Arizona. He gave me a copy of Betty’s book and told me I could take my time reading it.

With all this attention, I was living a delightful life—days of flattery, nights in “Arabia.” There’d be spasms of guilt—why wasn’t my mother writing me? how were the kids doing?—but when Constance urged me to move into an apartment she was taking on Sycamore Drive in anticipation of her success, I did. She was in a whirl—acting with Danny Kaye, enjoying constant attention, makeup, costumes, publicity! Everybody on the set loved her, I could see that. Whenever I could, I hung out in her dressing room, and she’d rush in between takes, looking for me. How cute she looked in her straw hat or, in another sequence, in her army fatigues! Bliss!

WHILE all this happiness was being savored and all unhappiness suppressed, my old friend Cheryl Crawford asked me to direct a musical. Since I’d never done one, I was intrigued. This would be my last stage show, I told Constance, and once back east, I’d go into the details of the divorce. She was so busy and so happy, not only with her work but with the protestations of enduring love I’d made her, that one morning as she was taking off for work, I still in bed, she kissed me, so giving me her blessing, and was gone. I remember what I felt when I was alone: relief. I had another respite.

Back in New York, living in a borrowed apartment, I began meeting with Kurt Weill, whom I knew from Johnny Johnson, and with S.J. Perelman and Ogden Nash, whom I did not know. Weill and Perelman were preparing the “book” of the show, and Ogden was finishing his lyrics for the songs. Kurt, it soon became obvious, dominated this cabal of odd fellows. I asked him why they wanted me to direct the show. His response, spoken with the most persuasive conviction, was that they wanted the musical directed as if it was a drama, not in the old-fashioned, out-front staging tradition of our musical theatre. That style was dated now; Oklahoma had changed everything. After all, Kurt observed, songs were a continuation of the dialogue and should be so treated.

I’d read the “book” and heard most of the songs and told Kurt that although I’d liked the songs, I’d thought the book abysmal. (He must have told this to S. J. Perelman, which couldn’t have endeared me to him.) That would be my job, Kurt said—to make the dialogue scenes carry their share of the load. That was why they wanted me.

But despite whatever I did and despite Mary Martin, who could make an audience believe anything, when we took One Touch of Venus on the road for its tryout, the book was still foolish and boring. Nothing we had going between the musical numbers entertained the audience. The “miracle man” had not performed a miracle. Dissatisfaction with my direction was expressed by Sid Perelman; he said I lacked a sense of humor. He was right—I didn’t respond to the humor of his dialogue. Our audiences also lacked a sense of humor. His stuff may have read well in The New Yorker, but it didn’t play on stage. We therefore resorted to the solution most musicals finally come to: We cut the dialogue scenes down to little more than “bridges,” introductions to the songs and dances, so we could move as quickly as possible from one musical number to the next.

Kurt also had a complaint. He cornered me and, without referring to his earlier contrary instruction, said that his songs had to be sung down center, facing straight out front. He was as absolute about that as he’d previously been about his “continuation of the dialogue” concept. So I put Mary on a small, plain chair down center and told her to sing Kurt’s best song straight to the audience, person to person. The effect was enchanting. But after I’d done something of that kind to the other songs, there was nothing more for me to do except bring the talent on and turn it loose, throw light cues, time blackouts, and take the curtain up and down.

I was soon reduced in rank. Conferences were being held without me. The scenery that I’d planned with Howard Bay was attacked and, without my concurrence, replaced. I found out who was boss. Not me. I’d become a sort of overpaid stage manager, subservient to everyone else. I decided that this kind of theatre was another species, one for which I had no talent. But that didn’t save my pride.

Nevertheless the show, by the time we got to New York, was an enormous success—three in a row for me. Why? How had that happened? This time I faced the facts. The dialogue scenes didn’t matter—even if they’d been better. The credit for our success belonged not to the “miracle man” but to three marvelous women Cheryl Crawford had brought together and to Kurt.

Mary Martin, our “Venus,” was then, as she is now, an extraordinary girl—“girl” at any age—full of the love of being loved. She did everything asked of her better than any of us could have hoped. She was also a completely devoted worker. One reason was the good fortune of her talent, another her training, another her beauty, and another that she was married to a man who, it seemed to me, was almost more her manager than her husband. He was, I could see, precisely what she needed to function perfectly, looking after her every professional and personal need. I’ve seen this kind of choice of mate with many stars—Katharine Cornell, for instance, with Guthrie McClintic, as well as some others who are still living so I won’t name them. This kind of arrangement enables these wholly devoted women to carry on their work freely. I cannot believe the sexual aspects of these unions are of great importance; that energy passes into their work.

The other two extraordinary women Cheryl had signed—the real miracle workers—were Agnes De Mille and her chief dancer, Sono Osato. Agnes is the most strong-minded stage artist I’ve known. She was absolutely sure of what she wanted to do and insisted that her wishes be precisely observed. She had choreographed the greatest success of those years, Oklahoma!; this had given her overwhelming confidence and the energy to overwhelm the rest of us. Kurt may have once wanted the show directed as if it were a drama, not a musical, but Agnes would not have tolerated any such nonsense. She immediately gave orders (to me) to have the stage totally cleared of all scenery for her dances. She wanted space! And she knew what to do with it. Her dances were superb set pieces, beginning, middle, and end, with what any true artist gives his work: a most personal theme. Her first dancer, Sono Osato, was a poem in movement. When she was on stage, I couldn’t look at anything else.

I was deeply impressed by the devotion and discipline of Agnes’s dancers. They never stopped working and had the commitment of fanatics. Few actors I’ve known have rehearsed with the continuous intensity of these “gypsies.” They lived on the floor of their rehearsal space and stayed there from the beginning of work in the morning to the end of their day at night. They were as devoted to Agnes as to a cult messiah—which is what she was. I used to sneak away from my silly “book” rehearsals to watch Agnes’s girls and boys work by the hour—hours I should have been trying to please poor Sid Perelman.

When the show was done, a question remained. I wondered whether, if I’d continued to direct the book and the numbers as Kurt had originally asked and if Agnes had gone along with his intention, the show would have worked. Just as I’d asked whether, if Helen Hayes had continued down the path my direction was pushing her, Harriet would have played 356 performances. It further occurred to me that somewhere along the line, every show needs a miracle from somebody, a performance or a gift that exceeds expectations. Harriet had Helen, this show had Mary, Agnes, and Sono—all four talents larger than life-size and more gifted than any of us had a right to expect. They’d made the shows. That’s why they were stars! And that was theatre!

AN EXPERIENCED woodsman can read in a wilderness evidence that you and I would not notice. He can tell what animals and birds live in the area, which of them are dominant, and who caught and devoured a grouse. I’ve seen those little piles of soft feathers in the woods where I live, and I saw and read the evidence on the Goldwyn lot the first morning I got back to California.

I’d left New York a few days after the opening of One Touch of Venus, having stayed only long enough to enjoy the long lines at the box office. Constance had not met me at her apartment, because she was working on another film, Knickerbocker Holiday. I was curious, of course, to know if she’d succeeded with Danny Kaye and Up in Arms. That film hadn’t opened yet; when it did, it would make or break her career.

When I walked through the front gate of the Goldwyn lot that morning, I ran into a pretty blond actress named Virginia Mayo. We’d met years before in Chicago, when she and Constance were in the “line” of a touring musical. Virginia was “going with” (that’s how they say it) a popular singer named Dick Haymes. (Now dead. Alcohol. Cancer.) Both girls were staying at the same small North Side hotel and had become chums. One summer night, we had a get-together on the hotel roof, all four of us. No, no swapping—those were unsophisticated times, and Constance and I were an exclusive thing. Now Virginia remembered me and said she was glad to see me in California. I asked her if she’d seen Constance, who was working on the lot, and when she said she hadn’t, I invited her to walk out with me and say hello, Constance would be glad to see her. Virginia said she was late for an engagement upstairs and hurried off. That’s all there was to that.

I found out where Knickerbocker Holiday was being photographed. Goldwyn had loaned Constance out to play opposite Nelson Eddy. She’d written me this piece of news, and I hadn’t responded. It was certainly what an Englishman might call an “awkward” combination; Constance didn’t sing and Eddy didn’t act.

I waited for the red light outside the stage door to go out, then sneaked up close to where the production was working. I saw a melancholy sight. There was my girl, rather overdressed in a costume of the Revolutionary War period—I’m talking about 1776—sitting in an isolated chair and reading a book. I don’t know exactly why I thought this a bad sign, but I did—the reading, I mean. No one was interviewing her, no one running lines with her, no one fussing with her makeup and hair; no one was kneeling at her feet, begging for an autograph. There she was, the heavy dress pulled up over her knees, reading, all alone.

She was overjoyed to see me, playfully threatened that the next time I stayed away for so long, she’d get another fellow and so on—but the kidding didn’t have the old bite. Or was I reading something into her calm? I pulled a chair up close. “I saw your old friend Virginia Mayo,” I said. “Oh, great. Where?” “Here. On the lot. I told her I was coming to see you and asked her to come along, but she had somewhere to go.” “We’ll get together,” Constance said, taking my hand, “next week. I’m so glad to see you. I missed you. I miss you even when you’re here.” I kissed her. She looked pleased. “How’s your pal Sam feel about the film? Up in Arms, I mean.” “Oh, fine,” she said, “so they tell me. I don’t see him so often now. He’s awful busy—” She stopped, then she said, “What’s she doing here?” “Who?” “Virginia?” “I don’t know; she didn’t say.” Which was when they called her and the makeup man came to check her face. As she walked away, she said, “Don’t watch now; you make me nervous.”

I walked away and so ran into the little gimpy wardrobe man who’d dressed me a couple of years before for my Dead End test. He said hello, and when he turned to look at the rehearsal, I did too. He was always a taciturn fellow, but he said something to me then which I’ve not forgotten. I don’t believe he knew I was “running around” (that’s how they say it) with Constance, because he pointed to the actors working in their Revolutionary War wigs and he said, “See those costumes? There’s never been a success in those costumes.” I nodded and walked over to the cop at the door and said, “Tell Miss Dowling I’ll be back.”

I knew where to get the straight dope—from the cutter. (They call them film editors now, although the fact is that any good director does his own editing.) This one did all Goldwyn’s work, an old acquaintance from the days when I was on the lot testing and trying to learn something about film direction. He was bent over his Moviola and had long strips of film on his racks, filling a great gray barrel and all over the floor. He did know of my interest in Constance. “How’s it going?” I asked, after telling him a little about the success of Venus. “The Eddy film?” he said. “Pretty good.” In Hollywood, great means pretty good, good means medium poor, and pretty good means lousy. “She photographs well,” he said, and he tore a frame off a strip of film and gave it to me. I did a quick study, said, “Yeah, she’s a pretty kid,” and then said, “Actually I mean Up in Arms.” “Pretty good,” he said. “Who’s this?” I asked. I’d noticed some strips hanging from a separate rack, and lifted one close. It was Virginia Mayo. “Somebody he’s testing,” the cutter said. “For what?” “I don’t know,” he said. “In general. For the future. Who knows? I read where you’re going to be a director here. Smart boy.” “Yeah, I didn’t have much of a future as an actor, did I?” “You’re not Gary Cooper,” he said. “Speaking of the future,” I said, “and since you’re being frank, tell me this: Are there enough films on Mr. Sam Goldwyn’s schedule for him to need two blond look-alikes?” “Saturday,” he replied, “I’m going for albacore in the Catalina channel.”

On the way to Connie’s place, I added up the score. Just as high as Mr. Sam had raised Constance, that’s how far he was preparing to drop her. He’d encouraged the girl to believe she was a coming star. But if Up in Arms was disappointing—he must have had private screenings—the blame had to filter down. Kaye couldn’t be blamed, because Goldwyn had him on a long-term contract. The director couldn’t be blamed; he had a track record and was in demand elsewhere. That left—

I got to the apartment before Constance and found her sister, Doris, there. She boasted that she was seeing Billy Wilder, praised his fidelity, saying, “He’s not a weasel like some other guys in this town.” Then she told me Billy was giving her a part in a film about a drunk that he was making.

Later Constance told me that after I’d left, she’d run into Virginia Mayo in the makeup department and when she’d suggested that we might all get together over the weekend, Virginia said she had plans to go out to the desert. “She seem changed?” I asked. “She sure got nervous,” Constance said.

I didn’t know if Constance had caught on by then to what was happening to her. She was innocent as a child in bed that night and had to be gentled more than she used to need. I felt so sorry for her, felt that I’d taken advantage of her goodness and her innocence and her youth. She kept repeating the phony optimism her agent had pumped into her to hold his client. I had a terrible fear that in this place, where only the tough survive, this nice girl was about to be eaten alive and left in a little pile of feathers.

Also that because of my behavior, I was one of those responsible, perhaps the chief one of all. I thought it was time to stop deceiving her. Although I hadn’t lied to her, I had stalled without telling her and was still stalling. “I’m going to accept her terms,” I said. “My wife’s. They’re stiff, but I’m going to take them. She got herself a lawyer; you should see him: Wall Street walking. From her father’s old firm. But I’m going to bow my head and take my licking.” “When?” she asked. “Now. I’m going back in a few days and finish it off.” And this time I meant it.

WHEN I got back to New York, I found that Molly had fixed up the small brownstone on Ninety-second Street beautifully. Here was all our old furniture, still standing by, as it were; waiting, it seemed. She’d arranged for the kids’ schooling and apparently they were doing well; she showed me their report cards. I went upstairs. The swing that used to hang under the doorway of the kids’ room in our old apartment was up again. Inside the room were sketches they’d made at school. I was relieved to see both kids looking so well. Molly was proud of what she’d accomplished on her own and had a right to be. She told me what she was doing at the OWI with Jack Houseman and Bob Ardrey—Nick Ray was there too—and I was jealous as well as admiring.

She was seeing an analyst, Bela Mittelmann. Her work with him had resulted in a greater firmness and confidence; now she didn’t want a divorce. She said she didn’t believe that, in the end, I’d continue with Constance, so she’d decided to wait me out. “You’re smarter than that,” she said in a tone I didn’t altogether like. She also said that if I ever hoped to get together with her again, I’d have to go to an analyst myself. That sounded like what it was meant to sound like: a threat. She was convinced—in a way that only Molly of all the women I’ve known could become convinced—that it was the only way for me to save myself. She urged me to go to Mittelmann. I suspected that this development was his idea, and there was an aspect of it I didn’t like—I was going to be policed by someone on her side. But I did go see Bela; I certainly needed help from someone.

Oddly enough, this doctor and I got along well. Why? He flattered me. He’d seen my plays and turned out to be a fan. After a couple of sessions, his basic attitude seemed to be that I was in better shape than Molly, that it was she who had the more severe problem. After all, I was doing successful work. This meant to Bela that there was nothing seriously wrong with me. But the result of this favorable conclusion was not what you’d expect or what he expected. I resented the man; I considered him treacherous to Molly. Obviously I was the one who’d made all the trouble. But Mittelmann, out of a mid-European male culture, was soon all on my side and, in a way, not taking my problems seriously enough. “If she continues as she is,” he said to me one day, “you won’t be able to live with her.”

AS YOU know by now, I always had more than one reason for doing anything I did—for example, hurrying back east. Despite the fact that I’d told Constance Venus would be my last Broadway show, I now wanted to direct a play by Franz Werfel, Jacobowsky and the Colonel. It was owned by the Theatre Guild, and they’d offered it to me. Rumor had it that the play was also being considered by Jed Harris. A victory in a competition with him would be to my taste. So I accepted the job and was introduced to its adapter, S. N. Behrman, or, taking him back to his Worcester, Massachusetts, origin, Samuel Nathaniel Behrman. Sam was an Anglophile, a man who treasured his friendship with “Willie” Maugham and that generation of English writers. Perhaps “friendship” is too mild a word. He revered these men, their work, their wit, their worldliness, their unyielding wisdom, and their financial substantiality.

Sam was a delightful man, and we were, for a time, close friends. I’d admired him, thought his work an extraordinary combination of wit, sophistication, and a warm heart. Sam, who had several times supplied the Lunts with vehicles for the stage, believed in magic, the magic of the stars. He was right; his plays needed the miracles these dazzling creatures provided to put them over.

He was the best listener I’ve ever known. At the close of a conversation during which he’d made me feel that I was an excellent talker, even a wit—accomplishing this by the “transference” of his own wit—he’d suddenly flag and for no apparent reason release a deep sigh. There was some mysterious anguish in the man. He was married to an excellent woman, but what need he had of her or she of him, or what had initially brought them together, I never found out. He often had a craving to be absolutely alone, so he’d engage a room in the St. Regis Hotel, high above the street, summon room service, order all the newspapers and a supply of cigarettes, and hole up for a couple of days, enjoying the silence and not answering the phone. He was a chain smoker, and although he bought suits and overcoats from Knize, perhaps the most expensive men’s tailor of that day, he soon had the lapels and fronts dusted with cigarette ash and the garment twisted out of shape so that it looked shabby. He loved to be seen in fashionable restaurants, and I can see him now, entering a gay room with a series of tiny, quick steps and beaming with the anticipation of pleasure—the conversation that was coming. Though he was a bit of a snob, and a name-dropper, I didn’t find this objectionable because his reasons for admiring whom he admired were worthy. He quoted his heroes, successfully arousing my admiration for them too. I always looked forward to our meetings. When he died, he left behind a diary inscribed in a tiny hand on hundreds of sheets of notebook paper. I imagined that what I’d find there would be more candid than his talk and spoil the loving memory I have of this man, so I didn’t read it.

Sam had been brought in to take over the adaptation of Werfel’s play by the Guild and one of its two directors, Lawrence Langner. One of Lawrence’s favorite theatre words was “comedic.” An Englishman who’d once been—and I believe still was—a patent lawyer, Langner had a strange way of working with Behrman. Sam would bring in some pages, Lawrence would read them, I would read them. Then we’d meet, and Lawrence would observe that Sam was like a cow producing a great deal of milk, so what he, Lawrence, had to do was skim the cream off the top and throw the rest away. Which is, bit by bit, what he proceeded to do, accumulating Sam’s “cream” slowly until he’d built an entire script. In the meantime, I was assigned a more difficult task.

The original play, which Clifford Odets had adapted—unsuccessfully, according to the Guild—was by Franz Werfel, the author of The Forty Days of Musa Dagh. Werfel had not yet agreed to S.N.B. as adapter, and Lawrence asked that I go to California, where Werfel was living among many other displaced German artists, and get his approval of Sam or at least a reluctant acquiescence. Long ago, Lawrence said, the Guild had done a Werfel play, Goat Song, and the production had not been to the author’s satisfaction. “You may find him a bit difficult,” Lawrence promised.

So I went to California and met with Werfel. I didn’t find him difficult; I found his wife difficult. She was the widow of the composer Gustav Mahler, and in case anyone forgot that, she called herself Alma Mahler Werfel. She ushered me into a darkened room, where Werfel was sitting waiting for me, as if she were permitting me the privilege of seeing an extraordinary art object, one so delicate that it might be shattered by an abrupt rise in my voice level. Just before we went in, Alma Mahler acquainted me with Werfel’s problem. “His heart,” she said, tapping her own chest. She introduced us in a hushed tone, then moved behind her husband and placed her hands protectively on his shoulders. I was seated facing the great genius—rather like a suppliant before a judge—and after a few nothings, I launched into my pitch in Sam’s behalf.

I didn’t get very far. Werfel had no problem with his voice level. It was loud. Why, he wanted to know, was his play being adapted? What was wrong with presenting a simple, straightforward translation of his work? Who here was a better writer than himself? I said it was a matter of the American theatre audience. At this he began to yell at me. He said Americans had no dramatic literature worthy of the name—this at the top of his voice. I interrupted him in an equally loud voice, denying what he’d said. Then I noticed that Alma Mahler, behind her husband, had quickly and urgently indicated the place in her own chest where her heart would be. I became quiet. Not Werfel. In an even louder voice, he began to attack America’s theatre, its films, its culture, and above all, the American character. “Savages!” he yelled. “You are savages here!” This was more than I could take, and I responded in a voice louder than his own. Immediately Alma Mahler waggled her finger at me and touched the place above her heart. I subdued myself, thinking of my mission. This byplay went on throughout the interview, and I got nowhere. All that happened was that I ate a great meal of abuse.

I told Lawrence on the phone that I’d failed. An experienced man with a lively legal mind, he observed that what couldn’t be accomplished by debate might be achieved by the transfer of certain sums of money. “He wants a better deal,” Lawrence said. Something of that kind must have happened behind the scenes, because Sam did indeed become the certified adapter of Werfel’s play.

I WAS wavering. One day I’d think: Is this the family I want—a sister who attacks me and a mother who hates me? Suppose Constance should get pregnant, and I’m stuck with this—do I really want it? Do I, for instance, want to live permanently in Hollywood? I’d think of the place on East Ninety-second Street that Molly had fixed up and her steadfast determination about me—she knew what she wanted. Me. She must have faith in a side of me she thinks worthy and in hazard. I remembered our kids, their faces and how they moved, and how she’d never turned them against me. I longed for them.

One night when Constance and I were making love, I suddenly thought of that damned analyst. I’d told this man about our lovemaking to make him see how perfect and precious it was, told him that we would often raise the top sheet up and over our heads so we’d be in a world where there was no one else, a perfect world. His response to this intimate confession annoyed me. He said we were a pair of prime neurotics, and when we raised the sheet up and over our heads—our “tent,” he called it—we were reaching for a perfection that did not and could not exist, a forgetfulness of all our problems through physical love. “You simply can’t get rid of your problems that way,” he’d said with that soft smile (which I thought patronizing), “because it’s all over in a couple of minutes, isn’t it, and there you are, right back where you started, in the same situation. Nothing’s changed, except that you’re tired and sleepy.” I got mad at him. “Yes, we may be neurotic as all hell,” I said, “and we may even be sick, but that is precisely what gives our physical relationship”—I used the plainer word—“its charge. You call it foolish and frantic; I call it wonderful!” I said this to him and he smiled that soft, patient smile as if he’d heard everything I’d said a thousand times from other equally foolish neurotics. But that night in California when I remembered what he’d said, I pulled the top sheet back down, and opened our “tent.” It was she who pulled the sheet up over our heads again, and that is when she said, “I wish there were only two people in the world—you and me.”

I’VE FOUND in my files of that year a letter from the friend in the OSS I’d written to. It reads: “I’m sorry to report that we are not allowed to hire you. The security check was unfavorable, I don’t know why but I assume for leftism. There is not a thing we can do and I’m truly sorry. If you’re ever in Washington, drop by and say hello …” And so on. A few weeks later, as I was preparing to direct Jacobowsky and the Colonel, my draft board upgraded me. Lawrence Langner rushed in for the Theatre Guild and asked that I remain 4-F so that I could do their play. I didn’t protest.

THIS PLAY was my fourth hit in a row, and I was now called the “boy genius of Broadway.” But I didn’t buy that. I’d had enough experience to take exception. There had been a miracle man on this show too, but it wasn’t me. His name was Oscar Karlweis. I’d never heard of him before the Guild brought him to me; I was told only that he was well known in Europe as a light-comedy and operetta star. He gave one of the most deft and light-fingered performances I’ve ever seen. He had a magic that overwhelmed the audience—they gurgled—and deserved all those worn-out adjectives the critics use: “captivating” and “enchanting,” for instance. He was both. He had charm, a quality the Group never mentioned—well, how can an actor be trained for charm? Oscar brought it in out of the blue. I didn’t know what to expect when I began rehearsals, yet he “made” the show. I had other good actors and many witty lines and a cute premise, but it was as much Karlweis there as it had been Mary Martin in One Touch of Venus and Helen Hayes in Harriet. I needed a miracle, and my madonna of luck brought me one.

Celebration after Jacobowsky

There is one thing I do commend myself for, a lesson I did learn. After a week’s rehearsal, I was disappointed in what I saw. I believed I’d got off on the wrong foot, directed the play as if it was a realistic drama when in fact it was a fairy tale. I was nervous about confessing this to the cast; would they lose faith in me? But I called them together and told them I’d directed the play as a Group Theatre drama instead of a light comedy, and we had to make a fresh start, from the beginning. I said I hoped they’d understand. Instead of losing faith in me, the contrary happened; the cast believed in me more. I’d told them exactly what they, without being able to articulate it, had felt about the way the show was developing, and they eagerly went back to the “top.” We started over again and I found that the important thing in my profession is to tell yourself the truth, not to be defensive or to rationalize, and to believe that your associates will appreciate being trusted with the truth. The show, at least for two acts, did turn out to be what Lawrence Langner called it, “comedic”; audiences were delighted. I realized how small the margin is for most plays between success and failure—five, perhaps ten percent. I was sure that if I hadn’t had Karlweis and if I hadn’t decided to trust the goodwill of my actors and start over, the production would have been a failure.

There is one sad note in my memory of that production, and it concerns Joe (J. Edward) Bromberg, one of the Group company I most admired. I thought he was an immensely talented actor when I joined that organization, a man who could play a great variety of character parts, but as we rehearsed I saw that something had been crushed in him. Lou Calhern, who was excellent in the part of the Colonel, was bullying both Joe and Oscar, but while Oscar deftly dodged and kidded Lou out of his domineering “fun,” Joe had no way, apparently, of defending himself. He behaved like a wounded man. I finally told Lou to lay off, and he did. But Joe still wasn’t himself. Later this was attributed to the blacklist and the anti-Communist pressure, but 1944 was early for that. Joe had traveled here and there, playing parts that were not worthy of him; perhaps this had wounded his spirit and his faith in his talent.

On opening night, he took me aside and thanked me for being patient with him. I didn’t realize I had been. I liked Joe and was glad to have done him some good. He went on, “I feel better now, although the migraines are still there.” He touched his head and I realized he’d been rehearsing and performing for weeks while suffering unrelenting headaches and had never complained to me. He was indeed a victim of stress of some kind, and I didn’t know what that was due to, didn’t ask, nor did he offer to tell me. Seven years later, I was to name him as one of the people in the Group’s Communist cell; Joe had died by that time, and what had been bothering him so deeply remained a mystery to me.

While we were still on the road with the play, in Boston, Constance used a publicity tour for Up in Arms to come visit me. The idea, supposedly, was to be photographed with Lou Calhern. She wore a rich fur coat—loaned by the Goldwyn people—and looked very much the movie star, but when we were alone, I could see that she was very dispirited. She revealed that her agent had told her Goldwyn was not going to pick up her option; instead, since she was still on salary, he’d sent her on the road to do publicity. She wouldn’t see me privately, but a few days later I had a call from her. Goldwyn’s people had put her up at the Ambassador Hotel (now razed) in New York, and she was there, sick in bed. She said she had a fever of one hundred and four, very sick for an adult. After that afternoon’s rehearsal, I rushed down by train. Arriving in New York about midnight, I went straight to her room. I’d not told her I was coming. When I knocked on her door, I could tell from her response that she’d been asleep. She had a candle in the room, the only light—it was easier on her eyes, she said. I got into bed with her and her body was burning. The fever made her passionate to the point of desperation. She cried and cried as we were making love and when she reached her climax, she shouted, “Goddamn you bastard!” Later in the night, half asleep, she said, “Don’t leave me. I’m so frightened. Don’t leave me.”

About a week after she’d returned to California and I to New York, I received a letter from a friend of hers, with a clipping from the gossip column of the Hollywood Reporter. It disclosed that Constance had been “seeing” (that’s how they say it) Charles Boyer. I couldn’t believe my eyes. Charles Boyer! When I read that clipped column item, sent anonymously in an envelope without a return address, I heard her sister’s voice, I heard the word “weasel” as it had been spoken by her sister. I recalled the history of how high Sam Goldwyn had raised her, then how, putting her in a fur coat his wardrobe department had provided, he’d sent her on a publicity tour to certain minor cities to squeeze every bit of value he could from his contract with her—which he was tearing up. He didn’t inform her of the bad news himself, had her agent tell the girl that he was dropping her like a hot rock; no, Sam didn’t put her on his knee to inform her of the end. As for my part, yes, I’d weaseled. It wasn’t an unfair word; it was the uncomfortable truth. I’d not told her the whole truth of my ambivalent feelings. Hers was a tragic story, and now I was eager to see her and comfort her and reassure her.

THE TRAIN west was no-man’s-land between the warring powers. It was also what they call a “safe house” now; no one would find me there. I’d have an uninterrupted three days alone. I’d read A Tree Grows in Brooklyn again. Of course, I’d read it before I’d agreed to do the film, but that was once over, quick and light. I couldn’t even remember if I’d liked it. No, I hadn’t; not really. I’d thought it “soapy,” a tearjerker, corny. Now I had the chance to read it slowly, as the director who was going to put it on the screen.

I was overwhelmed by it on that second reading, cried and had other emotions of a most personal kind. Perhaps it was because I’d just seen my children and felt my loss of them keenly. Perhaps it was because I saw no solution ahead for me, so was sympathetic to the man who was addicted to alcohol. Perhaps the figure of his ramrod wife reminded me of everything unyielding I admired about Molly. This, I saw, was the first piece of material offered me that made me think about my own life and my own dilemma. The dilemma of all the people in Betty Smith’s novel was mine and Molly’s. The little girl, who loved her father absolutely despite all, felt what my daughter, I believe, was now feeling about me.

I realized that I’d never directed a play that meant anything personal to me. My career up to then had been that of a mechanic, an able technician. Doing plays that meant very little to me, I’d gained the reputation of a myth. It was the triumph of the disconnected. I went over the four plays that had brought me to the eminence I occupied. Wonder boy of Broadway! Miracle man! Indeed! In each case there had been someone, not me, who was the cause of the triumph. I had had four smash hits and had accumulated this mystic reputation and—for a time—enjoyed it. But now it had suddenly gone sour and I was full of doubt. On that lonely train ride, the myth collapsed. When I arrived in southern California, I felt like a beginner again.

I’LL HAND her a surprise, I told myself. Was that my motive in not informing Constance I’d arrived? I wonder. I’d made a reservation at the Garden of Allah, a cluster of gloomy cabins around a swimming pool no one used. I’d heard that many famous writers had lived and drunk there. The name suggests romance, but my mattress was soggy and the wall behind the bed vibrated to the rhythm of the traffic on Sunset Boulevard. I was blue and did what people in the entertainment industry do when they’re melancholy: I called my agent. He sent over one of his lieutenants with a bag of optimism. “Bud Lighton’s wild about you,” he said as he drove me to Fox.

I found Lighten reserved and quiet, not wild. I told him I liked the book. “She caught an emotion,” he agreed. We were waiting for a call from our boss, Darryl F. Zanuck, to come and confer. Apparently Lighton was accustomed to waiting. How leisurely things moved there! When word came that our appointment would not be until after lunch, Lighton suggested that I spend the time settling into my office. He made a call and the executive in charge of office assignment, a special department, hurried up to show me my space and make sure I was pleased. Bud also called Transportation for me and arranged the loan of a studio car.

Offices, their location and size, the number of windows, private bathroom, yes or no, had the same meaning they have now: status. I’d never had my own office before and was both flattered and put off by its overstuffed comfort. The office-assignment executive, anxious that I should be pleased (in case I ever became a real big shot), kept waiting for me to ask for something more or point out a feature I didn’t like. I made something up. “May I have a large bulletin board clean across that wall?” I said, with a sweeping gesture. “Of course, of course.” He seemed relieved that was all I wanted. As he left, a young woman came in and introduced herself. My secretary. “I’ll always have coffee ready,” she vowed. Then I was alone, stretched out on the sofa.

Should I call Constance? No. I was in an unharmonious mood and valued the quiet. All my life, whenever I’ve committed myself to a job, I’ve immediately wondered how I could get out of it. What a giant step away from my family I’d taken! Did I really want to be exiled here for six months? Did I really want to make the film? Lighton called me back to his office. I had no way out of it now.

D.F.Z. had again postponed our meeting. “It’ll be tomorrow for sure,” Bud said. I was surprised at how patient he was. “In the meantime.”—he lifted a bound manuscript off his desk—“here’s what I have. Two acts. Working on the third.” He nodded toward his desk in the other room, where I saw an elaborate apparatus of thick lenses and adjustable frames. I realized that Bud Lighten was near blind. Also that he was rewriting the script; I was never to meet the authors whose names were on the screenplay.

Back in my office, there was a message from the William Morris Agency: Mr. Lastfogel had invited me to dinner. During those years, dinner with Abe was either at Chasen’s or at Romanoff’s, both extensions of Lastfogel’s work space. This night it was Chasen’s, and there was an impressive parade of stars, moving from the establishment’s entrance to their reserved tables. As they passed us, they left their salaams at Abe’s feet. I met Spencer Tracy and was surprised at the respect he paid my agent.

Sitting at Abe’s side was his wife, Frances. The Lastfogels appeared to be a down-home couple; they might have been the owners of a delicatessen on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Frances had been a small-time singing comedienne up until recently—even though married to Abe, who certainly didn’t need the money. I’d caught her act in Philadelphia, three comic songs in three ethnic accents. She was looking around the room threateningly, and as people passed our table, she seemed to be warning them not to show her husband less respect than he deserved, which was total. Abe was a king in the film world during those years, and Frances treated the biggest stars like kids around the block, giving them affection and, at the same time, a reprimand in advance. They’d better behave, for just as her husband was kindly, she was not; no, she wouldn’t stand for any nonsense.

Sitting with us was Abe’s partner, Johnny Hyde, an equally powerful agent because of the important stars who’d entrusted him with their careers. Johnny was famous for finding Lana Turner sitting on a drugstore stool. He was as short as Abe, both men five foot five. When I first met Johnny I thought he was Irish; he had a ruddy “Donegal” complexion. But it turned out that his parents had come from Russia and their name had been Haidebura. His florid flush was due to the overactive pumping of a straining heart. Seated at his side was his devoted companion, a fair-haired young woman, not blond, not straw, not platinum as she later would be, but a lovely natural light brown. She had the classic good looks of the ail-American small-town girl, and when she looked at Johnny, she gave him that dazed starlet look of unqualified adoration and utter dependence. Clearly she lived by his protection and was sure of his devotion, for every so often he’d slip his hand under the table in her direction. The girl gave me a glance but was careful not to look too long at any male. I was introduced but didn’t take the trouble to catch her name—I usually don’t the first time around. Later I found out that with the advice of her agent-lover, she was changing her name. It had been Norma Jean Dougherty; it was to be Marilyn Monroe, a synthetic name as serviceable as most.

That union had a characteristically (for Marilyn) tragic ending. Johnny, although he maintained a hustling front like any good agent, was not to live much longer. When he died, it became clear how fierce his family’s hatred for Marilyn had been. I believe her devotion to little Johnny was as pure as it was for anyone the rest of her life, not mercenary as the family chose to believe. She was at his side when he died, but the body was quickly taken away and she was forbidden to come near it. She learned that Johnny was “lying in state” in his home and that some of the family were staying there with the body. Late at night, she used her keys to enter the place. Whoever was guarding the corpse had gone to bed; the candles had burned low. Marilyn told me she climbed on Johnny and lay on him. In still, silent love she stayed there until she heard the first stirring of the family members in the morning. Then she slipped out of the house—alone in the world.

BY THE TIME I got to Constance’s place and was making up my excuses, it was past eleven, and when I rang the bell, there was no answer. I sat on the stoop, waiting, but decided that was an embarrassing position to be found in, so I walked across the street, sat on the curb against the wheel of a parked car, and kept watch down Sycamore Drive. In an hour, I saw her coming, prancing on those dancer’s legs, and with her a man, older than I and bulky around the middle. He was doing the talking, she was listening diffidently, nodding her head as if to say, “Yes, yes, I see what you mean, of course, that’s very interesting!” I figured that her companion was some species of intellectual and that he was directing his persuasion pressure to where she was weakest, her uncertain schooling. What powers these intellectuals have over first-blooming young women, I thought, as they passed into the dark courtyard, he clattering at her and she looking up at him with trust. Turn your back on a delicious girl in Hollywood, and before you know it, some high-dome is at her with the solution for her troubled life. It’s not the good-looking young athletes you have to watch out for but these idea-peddlers, who get in there by filling the gaps where the young woman most needs reassurance.

I followed behind the bushes to where I could see her front door, arriving just in time to see her unlock it and see him, still talking, follow her in and the door close behind them. Inside, the overhead fixture went on, then off, leaving two discreet lamps lit at either end of the sofa—the same sofa where we’d made love so many times, my feet up against the end where his plump butt was now nestled. She came to the window, the light silhouetting her like the shot of a movie star setting the mood for a seduction scene, and slowly closed the curtains.

No, he didn’t stay all night. I made sure of that—sat in the courtyard, lowering my head whenever anyone passed. About an hour later, the door opened and out he came, turning his back to receive the ritual good-night kiss. But it lacked the heat that whoever it was might have been hoping for; there was a troubled slump to his shoulders as he walked away. He was still talking—to himself. I waited a bit more so it wouldn’t occur to her I’d been waiting outside a long time—I still had some pride—then rang the bell, and in time she opened the door a crack, the latch chain secured, and saw me.

After we’d made love, I told her what I’d been doing, and she asked, “Why didn’t you come right in?”

“Was that Charles Boyer with you?”

“Are you kidding?”

“Well, who was it?”

“I won’t tell you.” And she didn’t. “What did you think I was doing in here? Were you hoping he’d stay all night so you’d have something on me?”

I told her about the squib in the Hollywood Reporter. She said she didn’t know anything about it. I didn’t believe her but let the matter drop. Despite the mistrust, I was delighted to be with her again. She too? I think so. But a few nights later, she told me Capa had written again, asking her to marry him. She liked Bob Capa very much, she told me.

Her sister moved out—to be with Billy Wilder, I assumed—and I moved in. We were now recognized as a couple. I gave her address as my own (but not to Molly). Every time we made love, with the excitement and all, I’d say, “I love you, baby, I truly do love you.” And she’d say—after she’d cooled off—“I don’t believe you. If you did we’d be married by now.” After which I’d back into silence or change the subject, and Constance would look at me, nod her head, show her teeth, and say, “All right then, all right then, all right!” I didn’t know what that meant but did recognize the tone. Threatening.

WE FINALLY had our first meeting. I tried to look at Darryl without a preconception, freed of his media image. D.F.Z. was, I saw, a small, hyperactive man with beaver’s teeth under a mustache filter. He shook my hand in a most unconvincing manner, then hurried back to his desk and picked up a polo mallet in the same way someone else might have lit a cigarette. As he talked, he swept back and forth through the open areas of his office, aimlessly it seemed to me, unless his purpose was to relieve himself of an excess of energy. A plump, motherly secretary was seated at the side of his desk, making notes of everything he said, lest any of us later had questions about Darryl’s wishes. I’ve forgotten what he said and even what his concerns were; they must have had to do with A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, but I was too fascinated with the man and his behavior to pay attention. I thought, afterward, that a great deal of his spouting was self-hypnosis, as if the sound of his voice bolstered his confidence to the level necessary for his position and his work. If he was feeling a personal interest in me, I wasn’t aware of it; I was to learn that his impression of me would depend entirely on the film footage I produced. Fair enough. I did notice that Bud Lighton was most respectful and, perhaps because he noticed I was silent, spoke bits of deference for me. I would nod, “pan” my eyes back and forth as the little man did his “turn,” and stare in what must have been a ludicrously fixed manner. Then, suddenly, it was over, and we went back to Lightens office. “What did he say?” I said. “It was a good meeting,” Bud said.

I was in a new world now and in daily contact with two extraordinary men, both born in Nebraska, forty miles apart, but as different, one from the other, as men in the same trade can be. I came to respect both these men, neither of whom had come out of the theatre or the left, neither of whom could be called an intellectual. Both Darryl and Bud had started as writers of silent pictures, and both were to influence me. They represented opposite aspects of filmmaking in Hollywood, and together and in contrast, they stood for the best of a breed that has vanished.

Hollywood is now what it was then, an art organized as an industry. Since this is America, there is conflict. Darryl was hung up on both hooks. When it came to a choice, the manufacturer won. Darryl made a program of films, as many as twenty-five a year. Lighton was a craftsman, made one film at a time. Darryl ran a factory, ran it perfectly; he was the best executive I’ve ever known. Lighton ran his “one-film-at-a-time” unit. Darryl competed with the other tycoons of his day. Lighton competed with himself, strove to reach his own goals. Darryl lived only inside his studio; it was his whole world. Lighton kept a fine-worked western saddle in his office, “to remind me of my cows.” He was, or behaved as if he was, eager to get back to his working ranch in northern Arizona.

Every day at shortly after one o’clock, Darryl swept out of his office, accompanied by the producer or director with whom he’d been conferring or a distinguished guest from “outside.” Following him came staff people and those whose Darryl’s departure from his office released from theirs. It was like the movement of a flotilla of warships, Darryl the command battle wagon. On the way to the executive dining room, where his chair was waiting for him at the head of the long table, he’d receive the salute of those he passed; everyone he acknowledged with a greeting was proud of it.

Bud Lighton walked to lunch alone. He didn’t eat in the executive dining room; he had his regular table in a corner of the common cafeteria. If you saw him and he “looked through you,” you recalled that he was near blind. People respected him but didn’t talk to him.

As a manufacturer with the responsibility of turning out the yearly program of films required to fill the theatres his company owned, Darryl made what he felt the public would buy. He was to film the first popular drama about anti-Semitism in America, but I doubt he had strong feelings about the theme. The success of the Laura Hobson novel Gentleman’s Agreement indicated that there was a large public ready for the subject. Nor did he show me a feeling for blacks when he made Pinky. Its theme was in the air, so it was economically feasible. Darryl was interested in whatever would make a good story. As for his politics, he made an expensive film about Woodrow Wilson, was pro-Roosevelt for a time, admired Wendell Willkie, later came out for Nixon. What was he for? Successful movies. Giving the public what they’d buy. He did have one genuine political conviction: patriotism.

Lighton made films one by one to satisfy himself. Each film he made contained the same themes, the same values. He had convictions, felt them strongly, talked about them constantly. They dealt with individual standards, never politics; with courage and decency, privileges and responsibility. He was against the New Deal of Roosevelt, believed that a real man would not accept relief, that it amounted to pity. He despised the East Coast, its ideology and the civilization there. He was for the frontiersman, who lived on a large tract of semiwilderness and asked no favors of his neighbor or of nature, the man who lived where he couldn’t hear his neighbor’s dog bark. Lighton despised communism but despised “liberals” even more.

This was the first time in my life that I disagreed with a man’s politics and loved the man. Suddenly political choice seemed less important. Bud aroused something more fundamental in me. Call it pride and individualism, speaking out on your own, asking no favors, fearing no one, enjoying courage in the face of adversity. When I listened to him, my left-wing positions seemed provincial, my convictions shallow. He appealed to that other, more conservative side of my ambivalent self. What a shock it was for me to like this man as much as I did! Had I really believed what I’d said I believed? Did I really give a damn about politics? I did, yes! Maybe less, but still. Then how could I like this man as much as I did?

Zanuck’s aesthetics were simple; they were out of the Warner Brothers product book: adventure and excitement, clash and drama, did he get her, did she him? He cared very little what the clash was about, as long as it could be made dramatically valid. When it came to casting, Darryl liked personalities, “stars” who could carry a picture, whose names on a marquee or in an advertisement would attract a large, loyal public. But with a few exceptions—Ty Power, Orson Welles, Clifton Webb—he didn’t think of them as people. They were useful to help sell his product. Darryl was a captive of his corporate obligation, of a ravenous ego, and of his past. He had to succeed.

Lighton’s work goal was to capture a single, strongly felt human emotion, one he believed in himself. His view of actors was that of all the old “tough” directors—Ford, Hawks, Raoul Walsh, William Wellman, Henry Hathaway, and his particular favorite, Victor Fleming. These large, intemperate men, dominating their sets with the threat of a violent temper at the end of a short fuse, were scornful of what they called “New York actors.” They would say that if an actor knows he’s heroic, noble, or good in a part, it wouldn’t work so for the audience. Bud despised noble posturing above all else. “When a man gets angry in life,” he’d say, “he’ll walk away. If he’s sad, he’ll conceal it. Emotion is and should be private. Actors are proud of their emotions; they show them off. When they do, I don’t believe the scene.”

Darryl was a sensualist, so they say. Maybe so. A small city boy out of mid-America often has his ego hitched to his fucking. Many stories are told about Darryl: for instance, that a starlet was brought to his private office at the end of every afternoon and so on. It’s probably true that a pretty young woman was a challenge to him—but that might mean that her proximity uncovered an uncertainty that he wanted to quiet. As for the rest, what do we know about what happens after a door is closed? When you look at his films, you must believe he was much more comfortable with men than with women.

Lighton, at six foot one and one hundred and ninety-five pounds, was married to a woman several years older, who, soaking wet, may have weighed eighty pounds. According to Henry Hathaway, a close friend, they had no sex life. Henry describes how Lighton relieved himself of unused energy by getting out in the morning sun and practicing with his bullwhip, as the perspiration ran down his face. An ascetic in every way, he romanticized women. He called Dorothy McGuire, whom we cast in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, “Angel,” which effectively robbed her of her sexuality. He disliked Constance the first time he met her and never again talked to her after they were introduced. He liked Molly a great deal, although he never met her. He thought her the right woman for me and admired in her the quality he most admired—devotion to the good.

Darryl’s taste in glamour ran to French singer-actresses; they brought out all his cultural uncertainty. His idea of a glamorous residence was the George V in Paris, which was as close to a Beverly Hills hotel as a French hotel can be. He admired what he felt he lacked, international snob sophistication.

Lighton was not impressed with the society or the culture of the capital cities of Europe. He liked best the men he was working with on a film and the foreman who ran his ranch. He was most at home with his cowhands.

Despite all rumors about his private behavior, Darryl was a devoted family man. He did abandon his wife and home to live in Paris with a French singer-actress in 1956, but he didn’t skip out and disappear. He made damned sure that each of his three children and his wife were protected with enough money so they’d be secure. Years later, when the company lost a fortune of money and the board of directors and the owners of the stock insisted on a change, he had the responsibility of relieving his son, Dick, of his position as vice-president in charge of production at Fox, a position into which Darryl had put him. People were shocked at Darryl’s act, but my opinion is that he preferred to lire his son himself so it would be a protective paternal act, with as little pain for Dick as possible. At the very end of his life, when Darryl was sick and hurting, he returned to his wife and lived out his last years with her. She was the protection he valued most.

Bud Lighton, after the death of his wife, Hope, and a further deterioration in his eyesight, sold his beloved ranch, bought a house on the warm Mediterranean island of Majorca, and lived there until his death. He died alone. Perhaps because he had no children, his best films dealt with children, and the most touching scene in the film I did with him had to do with a ten-year-old girl. Bud conceived her scenes with genuine feeling.

People used to make fun of Darryl’s vanity, but it was no greater than that of the other tycoons of his day. As contrasted to the products of the film businessmen today, each film these older fellows made had to be the best that came out of the colony that year. They had to beat their competitors—Darryl over Jack Warner, Sam Goldwyn, Harry Cohn, Louis Mayer, David Selznick—to the Oscar. Darryl spared no expense or effort, time or money, on the films he made that were his “personal productions.” When, on Gentleman’s Agreement, I thought a scene I’d done was not as good as it might have been and asked to be allowed to shoot it over, he didn’t hesitate. “Sure, go ahead, tomorrow,” he said. It was his film!

Bud had an equal passion, but it was quieter and revealed itself in a different way. He talked over each scene I was about to shoot, telling me the feeling he hoped he had put into it and now hoped I could get out of it. He talked of humanity, feeling, courage, pride, all the old-fashioned “American” values of the frontier society that he admired. Some people thought A Tree Grows in Brooklyn sentimental and corny, but I was sympathetic to what Bud stood for and did my best to help him realize his vision.

To all these men of that day, film was everything. They had to surpass all their own past creations, their dreams and hopes, each time they “went to bat.” Beyond this quality of commitment there was something else Darryl created: zest, a passion about filmmaking, communicated to those working on a film together. Darryl had brought together the best cameramen, the best designers, the best actors, the best technicians, all of whom were there because he’d sought them out, he paid them well, and he’d been able to convey to them the importance he attached to his program of films. When this little man walked down the street from his office’s side door to the executive dining room, everyone watched with admiration, noting who his guest was that day. It could be a politician, a famous author, the head of a rival studio. They believed D.F.Z. could hold his own with anybody. He’d go by, swinging his polo mallet or a cane, swaggering a little—who had a better right?—and he’d talk in a friendly way to whomever he passed. Yes, he was tough and he was able, but they also respected him for his fairness and for his affection for his own people. He made one unit out of that crowd of workers, technicians, and artists. All of them knew where they stood on that lot, whom they had to please, what they had to do. The old studios are gone today, but there was much about them I admired.

Finally there was another quality I, especially I, admired about Darryl: He wasn’t afraid of anyone. When the other studio heads, Jewish men, had qualms about making Gentleman’s Agreement, they asked Darryl to meet with them at Jack Warner’s dining room. He replied that, unfortunately, he was too busy to go to Warner Brothers’ studios at Burbank, but he’d send a distinguished guest in his place, Moss Hart. Moss, who was writing our shooting script, undertook the mission, went to Burbank, and sat down with these tycoons. They asked him to plead with Darryl not to make the film. Their point, as Moss later told Darryl and me, was that the Jews in this country were getting along fine now, so why stir things up—which this film might do. Moss reported that he was unable to persuade them that the film would not have a damaging effect.

Darryl ignored the frightened men and went right ahead with our project. The same thing happened when it was urged on Darryl by the Catholics who dominated the Breen Office that the heroine of our film must not be a divorced woman. Darryl was angrier this time. After all, the Breen Office was paid by the film companies; it was not its business to censor films but to see to it that they were made. There was no rule against having the heroine a divorced woman; those fellows were obeying another set of rules, from another authority. Nor, some years later, did the Mexicans get anywhere with Zanuck when they said that Viva Zapata! would be condemned in Mexico and cause a great wave of anger, one that might affect the reception there of all Fox product.

In all those cases, Darryl’s belief was that the audience was ahead of the moralists and censors; he proved correct each time. The important thing for all of us who worked at Fox during those years was that the man heading our studio didn’t back off when he was challenged.