Sundown Beach, the Actors Studio company (Photo Credits 18.1)

WHEN I’m interviewed now, I’m asked how the Actors Studio started. Here’s the answer, not simple but true.

When I came back from the Villa Verde Trail, I decided to spend a few quiet days in Manila, writing my report. I knew that if I went straight back to the States, I would never do it, and it seemed important for me to conclude the experience there—not for the Special Services Command; for myself. I was assigned to a small hut in the Chinese section. It had a dirt floor and, since it was not airtight, had no need of windows. On my first night in “civilization,” I went to see a film: Irving Berlin’s This Is the Army. After Tacloban and the Villa Verde Trail, after the stories I’d heard, this glamorization made me angry. It exhausted me with entertainment, one song, one tableau following another. It made show business out of a complex and tragic event in which so many lives had been cut short or ruined. Empty, easy patriotism and corn, it was typical of the Hollywood and the Broadway I’d begun to reject.

I went back to my hut, determined to find a place where I could type, borrow a machine, and start working the next day. But with the morning, I found that my head was hot, then, an hour or so later, that my whole body ached; it was burning up and I was very weak. I fell on my cot in a corner, the fever raging—yes, it happened that quickly. I fell on all fours, and that was a relief. Crawling to a corner, I threw up, then I was shitting with diarrhea and puking too. A few hours later I was barely conscious, and my only relief was in crawling here and there on all fours; the movement and the posture helped. This went on all night, getting worse, so that by the next morning I didn’t care if I lived or not. I was a dying animal without the will to continue.

“Well, now, how do you like it?” I kept asking myself. “How do you like it now?” What did that mean? During that year just behind me, when I was most in demand on Broadway, the boy genius with several hits running simultaneously, and a hit film all over the country, I’d been increasingly embarrassed by the acclaim I was receiving, believing that I didn’t deserve it in some cases and in others that it was coming to me for work I didn’t respect, not what I had in mind. Often I wanted to start all over again, a wish that I was to have repeatedly in my life—to be plowed under and come up again, to be brought down to my true level. I guess, despite the confusion of my mind due to the fever, I must have remembered this wish to be leveled, because it had happened—I was where I so often wanted to be, on the bottom again—and I was asking myself, “Well, now, how do you like it?”

My fever was the one called dengue, and it caused me for two days to lose the will to live. In that sense, I had the experience of dying. I “died.” But then the relief I got two days later, when the fever had cooled and gone, revived both hope and desire. I came out of it feeling weak but clearheaded. As I wrote my report about the “mission,” I made certain decisions about myself.

First I determined to take charge of my own life, to find a way to live professionally in which all artistic decisions would be mine to make: to do what I wanted, not what other people expected of me. I was not like anyone else, and I was not going to do what anyone else did. It would take time, but I’d find my own path.

I missed the Group Theatre, what it stood for and the life it made possible. I decided to someway create that kind of professional activity again. I had no idea how that might be done—it would be worked out a year later with Bobby Lewis—but my desire for my kind of theatre life and a determination to do something about setting it up: that was the start of what became the Actors Studio.

I also made another decision during those three or four bleak days in the cabin with the dirt floor, as my body cooled and my strength came back. That had to do with where I would live and how and with whom.

I suppose that even though the participants often don’t realize it, every marriage stops from time to time. Often it is not revived, stops for good—and forever. If it continues, often it is in name only. But other times it is truly revived and the participants reengaged. In that sense it becomes a different union, on a new basis. This is true not only in the relationship between a man and a woman but in the relationship between two friends. From time to time relationships have to be reexamined from both sides and especially so in a marriage, for you are marrying not only a person but a way of life; in fact, a culture. People to be true to themselves have to ask: “Is this way of life, the one I’m entering now, how I want to live?” Then decide to marry or not.

As I saw how Molly had saved herself and gone on, she too reevaluating and in that same sense becoming a different person, I admired her and consequently loved her more. It particularly impressed me that she had not turned our kids against me—that would have been so easy to do. As the crisis between us intensified, I valued her more, respected her more as we separated further. But what I cherished above all else was the way of life she brought with her, her “baggage.”

Then there was the matter of geography. In all the months I’d stayed in California, I’d never stopped longing for the East. It wasn’t because of the houses in Los Angeles, which I found, row on row, abominable; it wasn’t because I disliked the trees there and the not-green greenery; it wasn’t because I longed for the seasonal changes and the promise of moisture coming in the cool eastern air; it was, again, the rest of the baggage: the California culture that went with it, the culture of the agency offices and of the restaurants, Chasen’s and Romanoff’s; and the atmosphere of the executive dining room and the steam room at Fox and what went with it all; the gossip columns in the crummy newspapers and the Hollywood Reporter. I determined to go back to New York and set myself up there permanently.

I didn’t believe the report I was writing had value any more than I thought the mission that had brought me there had value. But the decisions I made about myself those last days in the Philippines determined the course of the rest of my life. Even though they were not entirely conscious, they stood up—God, how they stood up! Perhaps it had taken those two days when I was “dead,” crawling on all fours, head down over a dirt floor, an animal voiding at both ends until there was nothing left of my body, when I was alive but without resolve, will, or desire—perhaps I needed to come out of that and be reborn a different person, with a determination to create the life I wanted for myself.

During those last days, I received two letters. One was from Abe Lastfogel, informing me that Zanuck had not been able to hold Anna and the King of Siam for me. “Don’t worry,” Abe said, “you’ll have your choice of pictures here. Zanuck told me that he considers you the greatest directorial find of the last decade.” I wanted to duck that bouquet; it wasn’t what I thought of myself. As for “Don’t worry,” I wasn’t worrying now, not about that.

The other letter was from Molly, a loving letter informing me that I was going to be a father again. I was so happy, I cried. It was what I wanted most to hear.

A PLAY was waiting for me when I got home. Molly had read Deep Are the Roots, and she urged me to do it. We were healing; I’d returned the wedding ring she’d mailed to me in anger four years before, and she’d accepted it. She would give me another child, whom we’d name Nick. I was full of gratitude—like any good Greek—and eager to go along with anything she wished. The play dramatized the shameful status of blacks in the South, a theme that had my sympathy, of course. The authors were left-wing intellectuals like myself. All would be harmony. It was.

A black soldier returning home from the war is accused of stealing a watch, the heirloom of an old Southern planter. The mechanics of how the watch is “planted” on the boy, how a witness is terrorized to profess what she knows is false—all this would now seem, even to the authors, I’m sure, mechanical and manipulated. The old Southerner was—one of the authors later admitted—a villain drawn with a heavy hand. His blow-up speech to his daughter and her fiancé makes evident why this play is not revived today. “You’ll be drowned in a murderous sea of black savagery,” he warns. “The waves are already mounting high. They’re lashing wildly at every citadel. This black horde will return from Europe, stinking with rebellion and ready to turn their weapons on us, their masters. Nothing will be safe, nothing will be inviolate. It is either them or us.” It does sound like a speech from nineteenth-century melodrama, doesn’t it? But it worked with the audience of the mid-forties, and I didn’t ask that it be rewritten or that the character be altered.

After the play opened and became a hit, one of the authors, Arnaud d’Usseau, was asked to write about me. I quote because it describes the times and because of an unanticipated irony. “James Gow and I,” he wrote, “believe in writing a play from theme; Kazan believes in directing a play in the same fashion. There have been many brilliant directors in our Theatre; some of them have made much more of a splash than Kazan. But these men have lacked a certain moral fibre, a certain ethical base. Their brilliance, after a short while, has been dimmed by a certain irresponsibility in their art. Kazan does not have any of this; in fact quite the contrary. He has a tough-minded seriousness that convinces me that everything he has done to date is but a beginning.”

This was written in 1946. I can’t help wondering what my friend d’Usseau thought six years later when I testified in the cooperative mode before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. You can see why the position I took then was such a shock to so many people. What d’Usseau said was true. I do work from theme, but I no longer believe that a play or a film need affirm a stand in a social struggle. But in those harmonious days we all thought alike—or seemed to. We crowded all over a political position like birds of transit flocking on a great sea rock. To use a word current at that time, we were “correct.” In fact, we vied to see who could be the most correct. I believe that for a time it was I. After the play was a success, I became the “hope of the progressive theatre.” A critic wrote: “There is nobody in the Theatre or Movies today who can raise more indignation about human misery, poverty and the like than Elia Kazan.” Yes. Perhaps. Thanks for the good word.

But in my secret heart, I wasn’t quite such a good boy. “Correct” is a word in the liberals’ vocabulary that I shied away from. I didn’t want anyone approving my artistic political position. It was why I’d quit the Communist Party eleven years before. Reading Churchill’s speech at Fulton in 1946—an “iron curtain”!—I wondered if he was not right, in fact ahead of his time. The liberals called him a warmonger. But when Lithuania and Latvia had been gobbled up and disappeared, no one of my left friends protested. I was enthusiastic about the Truman Doctrine; I didn’t want the same thing to happen to Greece. My friends didn’t realize it, but we were drifting apart.

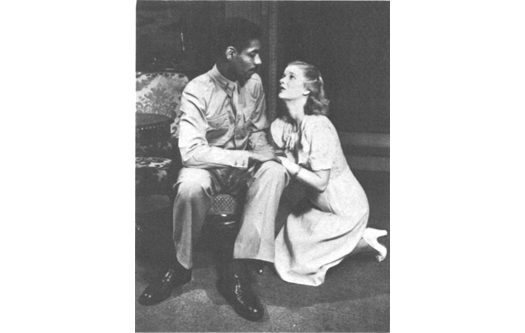

Gordon Heath and Barbara Bel Geddes, Deep Are the Roots (Photo Credits 18.2)

Deep Are the Roots was part of a flow of plays built on the drama of the falsely accused. This mode had started ten years earlier with Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour, in which two women who run a school for young girls are falsely accused of being lesbians. Lillian, a tougher bird than Gow or d’Usseau, pulled a switch and got to the real drama. In her third act, one of the women admits that she does have lesbian feelings about the other. With this turn, the play got down to a deeper issue: What if it was true, what then?

What if, in Deep Are the Roots, the returning black soldier coming back from an army that, as I’d seen, refused him weapons and further humiliated him by confining his services to driving trucks, digging ditches, cleaning latrines, and peeling potatoes, came back full of anger instead of being that fine, decent, patient, handsome black boy so purely in love with an equally pure white girl? What if he’d taken her to bed or to lie under a tree—she seemed willing enough, the way I’d directed the delectable Barbara Bel Geddes—instead of simply mooning over her? The real drama is revealed when the accusation is true. Black friends have said it to me plainly: We have a right to be sons of bitches too. As it was, all that remained for the authors to do was unravel the plot by proving the accusation was false.

The effect of treating a social problem in this way is that there is never any doubt in the audience’s mind as to what they’re expected to feel. They have the assurance from the beginning that they are on the side of the angels—the falsely accused. They have never been challenged to doubt. This, of course, does not prepare them for life as it’s lived. They are also often masochists—so it has seemed to me—enjoying the middle-class white man’s guilt about the black man. They’ve been told where to stand and what to think, and guaranteed safe passage to the final curtain. We are in a kind of conformity tide. That is a word liberals say they hate, and they do—except when it’s their own conformity.

Such a play is not drama that informs life; it is liberal corn.

Some years later, when the blacks rose in anger, filling the streets not far from those Upper East Side blocks where many of the affluent liberals lived, when they no longer followed Martin Luther King but rather Malcolm X and were impatient for an equal measure of everything good, when it was revealed that the people they hated most were middle-class liberals—especially if they were Jews—where were we then? Where was I? Hiding. We stayed off the streets at night, relied on our doormen to keep the front doors of our apartment houses locked, appreciated the security guards brought in and the new locks and alarms we quickly installed. “I have a dream!” was replaced by “The fire next time.” How had Deep Are the Roots prepared its audience for that day?

The most courageous man of all of us in that period was Budd Schulberg. He went into Watts while buildings were still smoking and stores being broken into. There he joined with the blacks, day to day, starting a class for their young writers. A few years later this group produced a book, From the Ashes: Voices of Watts. Budd’s devotion was heroic; it was also correct.

AFTER the success of Deep Are the Roots, Kermit Bloomgarden suggested that he and I form a production partnership. I gave his suggestion much consideration; he was an able producer and a close friend. But despite all that, I never looked forward to having dinner with him. Was that a reason? Yes. I knew what the talk would be; I’d heard it all. He, Gow, and d’Usseau were all fine fellows, but our relationship was cursed by the fact that we agreed on everything. I didn’t propose to settle further into that. Besides, many of my views were changing. I wasn’t where I’d been yesterday.

The only man in the theatre I knew who said anything that surprised me was Harold Clurman. He’d approached me also, suggesting that we form a theatrical partnership. I was attracted by his proposal. I was looking for a man smarter than I. I wanted brighter company. And challenge. I wanted to be close to someone who had more culture than I did. Harold had a subtler mind. He had a liveliness that made him an engaging companion. He also had something of the devil in him, so he understood human ambivalence.

I discussed Harold’s proposal with Molly, as I did everything at this time. Her Yankee spine stiffened. I persisted, told her I’d learned a great deal from Harold and still could learn. “He was always interesting,” I said, “always stimulating.” (By now her backbone was a ramrod.) All right, he had faults, I admitted—selfishness, intellectual vanity, Boulevard St. Germain des Prés arrogance, yes, and his damned inertia—but he was able to convert these faults into virtues. “He thinks I should be lazier,” I said to Molly. This didn’t go down well with my Puritan wife.

By a mode of reasoning special to wives, Molly blamed Harold for my infidelities. She didn’t mention this in our discussion, but I believe it was the reason she was so violently opposed to my entering a partnership with him. What she did say was that she didn’t think so damned much of his intellectual abilities; they’d been corrupted by his devotion to his now-wife, Stella. He’d let Stella make a liar of him, she said; I should know all about that. Had I forgotten Casey Jones? Didn’t I remember how he’d humiliated me?

I did remember. I let the matter drop. I had time to think—I’d contracted to do another play.

SAM BEHRMAN, the author of Dunnigan’s Daughter, was an endearing man, full of longing and pain, tremulous with uncertainty of every variety, and not a strong man in a crisis. He was a member of the Playwrights Company, dominated by Robert Sherwood. He was also dominated by his agent, Harold Freedman. And, for a time, he was dominated by me.

He had what the Japanese call a living soul. At sixty, he was still trying to grow and keep up with a rapidly changing world. He sensed that in the period after the war, the American businessman would try to take over the world. A new kind of imperialism was appearing, one not enforced by armies and garrisons, as were the colonial imperialisms of the previous century. The American businessman was going to make the whole world his colony, and the weapon with which he would gain his will was the sheer bulk of what he produced with the might of the dollar. In Mexico, a country that had attracted Sam’s interest because of its painters, our foreign policy was called “gringo imperialism”; its goals were to devour that country while keeping a friendly face.

I’d underestimated the play when I’d thought about it overseas because I’d underestimated its author. Using his own palette, employing his own special style, “high comedy,” Sam was making his statement about the world. American power affronted him because it frightened him. He felt for the tender gentlewoman who was the vortex of his play; she represented what he prized most in life, a warm heart and a civilized mind.

Sam and his plays needed a miracle man, someone who’d take over and fulfill his dream for him. Because of the success of Jacobowsky and the Colonel, I’d become Sam’s hope. Opening night of that play, Sam sent me flowers with this note: “Dearest Gadg: Why should just girls get flowers? My feeling about you is first-love girlish, a tentative adoration. Tentative because I am unsure of your response; you are so masculine. But I feel deeply about our long trek together. It was good, it was very, very good. Call me tonight. Better still, come over.” Sam’s feeling for me I can only describe as the feeling a woman may have for the man who first brings her to orgasm, a temporary conviction that no one else can do it for her.

We’d been working on Dunnigan’s Daughter together, to deepen its social content. The central male part was that of an American businessman who possessed his wives without either enjoying them or helping them realize whatever human capabilities they had. The story had a metaphoric relationship to the practice of our industrialists in the world. We were out to possess a world, Sam was saying, that we didn’t understand or appreciate.

I’d cast the play uncertainly. It was a difficult cast to serve with actors because, while they had to be able to handle comedy lines, the performers had to be more passionate than those generally chosen for Sam’s comedies. The woman at the core of the play had to be a model of feminine sensitivity—and humor. The businessman had to be something besides a villain. The audience must know without being told why the heroine had married him; they should feel potential unrealized in both people. Sam’s tone was one of tenderness, compassion, and understanding.

The play was an abysmal failure when it opened on the road for its tryout. There was, however, one “rave” notice: “Mr. Behrman’s new play is a good and fine play, a work with character and nobility of purpose, with courage, honesty, conviction, strength and optimism. It is not, however, a likeable play; on the contrary it is a little uncomfortable. If you feel you have to laugh loud and often, you’d better not look in on it. But if you feel inclined to listen carefully, you will have an evening of inspiring substance.” This generous appreciation killed the play dead in Philadelphia; no one came to the box office.

When a road tryout is a failure in the commercial theatre, the forces of professionalism rush in. A play pleasing only to a limited audience is not acceptable. A serious play, particularly, must go “over the top”; it must, in some way, please everyone. Our two-week tryout stand proved not to be a tryout at all. We needed time and patience to work out our problems ourselves, but the old pros hustled in and took over. In the quiet way affluent men have, they were hysterical.

And I let them take over.

First among them was Sam’s agent, Harold Freedman, a man with an air of culture overlying a most practical core. A failure for him meant loss of income. Also, possibly, of a client. Harold Freedman had to see to it that the play succeeded. I knew what he was saying to me but suspected that he was saying something different to Sam and giving still another message to Lawrence Langner of the Guild. I soon began to feel a cooler breeze in our production meetings.

Lawrence Langner was plainer; I wrote down what he said. “Sam has become discouraged about using Mexico as a background,” he told me. “He’s afraid of getting bogged down in political and social problems. After all, he just wants to get some comedy.” Those were his words, and I translated them for myself: “Lay off Sam!” “Just get some comedy” must be one of the most cynical phrases in the theatre. The author’s theme, the reason he wrote the play, is ignored. It’s like summing up a love affair by saying, “All he really wanted was to get his end in.” I soon found that while I was talking into one of Sam’s ears, Lawrence was talking into another. Sam, in the middle, soon panicked. I lost face and power.

When producers don’t know what to do in the theatre, they recast. I was told that I had to immediately find a more “professional” cast and one that could “handle comedy.” Sam himself asked me, in the presence of the others, to recast four of the five parts. Since no one was buying tickets, something drastic had to be done, they said, or the play closed on the road. I saw how this threat frightened Sam. I felt for him. I did what they were asking.

What followed shamed me. Of course, the new cast didn’t help. Nor did the “high comedy” readings. Our theme of innocence tyrannized by power was gone. The play lost its meaning. When it was all over, everyone thought I was a fine fellow, easy to get along with, always pleasant to talk to, and most cooperative. But the play died. The experience had a lasting effect on me. I began to ask: Shouldn’t I protect myself as a director by becoming my own producer? Shouldn’t I reconsider Harold Clurman’s suggestion that we become partners and our own bosses? I thought about that, and the next stage play I did was billed “An Elia Kazan Production,” so giving notice to the backers, the agents, and everyone else not responsible for the creative work that the production power was in my hands. People in the theatre, particularly producers, thought this billing arrogant. I want to say a word about that.

SOME years ago, after a disagreement over a personal matter, I abruptly withdrew from a film that I was going to direct, whereupon the author of the book that was the source of the film, a man who was also the coproducer of the movie, wrote a letter breaking off our relationship from his side and offering as his reason that I was impossible to deal with because I was an “arrogant Anatolian.”

The “Anatolian,” of course, was accurate. The “arrogant”? I was elated by this characterization. “At last,” I said to myself, “I’ve made it. It’s what I’ve always wanted to be.” I believe every artist is, as he has to be, arrogant. You may not go along with that; the word has unfortunate connotations. But whatever else an artist may be saying in his work, he is certainly saying, “I’m important!”

Arrogance, when it’s depicted on the screen or stage, is usually projected by boisterous behavior. Not so in life. The most arrogant people I’ve known—people whom I admire for this quality as well as for the work they do—are often quiet with the special ease that comes from being sure of themselves.

Artists are different from other people, and they do behave differently. I’ve already expressed my opinion that vanity—one of the seven deadly sins—is often a spur to creation in a filmmaker. Now consider the seven deadly virtues for the artist. Here are seven: Agreeable. Accommodating. Fair-minded. Well balanced. Obliging. Generous. Democratic. You don’t agree with my choices? How about these: Controlled. Kind. Unprejudiced. Yielding. Unassertive. Faithful. Self-effacing. And for good measure: Cooperative. They are all deadly—for the artist. They add up to what is suggested by “nice guy,” “sweet,” “pleasant,” “lovable,” “on the side of the angels.” None of which any artist is, should be, or ever has been. If he seems that way, he is concealing his true nature. He should better be a disrupter, on the side of the devil. In the years ahead, every time I was a nice guy, cooperative, and yielding to the point of view of others, I had a disaster.

Arthur Miller has become, as he had to become, a stubborn, unyielding man. There have been times when, despite a fair-minded and democratic front, he has unmasked a truer self. When he has been dissatisfied with the rehearsal performance of one of his plays, for instance, he has stepped over the prone body of his director and lectured his cast. His theme was always the same: “My reputation is international, and it is at stake here. For the time being, it is in your hands, and you are failing me.”

A contrasting instance is that of Bill Inge, but his gentleness on occasion amounted to self-betrayal. In a crisis, rather than protest, he’d leave town to avoid unpleasantness. The arrogance of Miller was truer and more effective and easier on the psyche. Inge died young. Miller is still going strong.

Did you see the photograph of Mike Nichols, a fine director, on the front page of a recent issue of The New York Times Magazine? Did you notice how he smiles, how charming and friendly he seems—at first glance? Then look again and notice the glint in the corner of his eyes, recognize the cunning and determination there, the hardness? Why not? It’s what saves us.

Read the letters of Ernest Hemingway and ask yourself was anyone ever more intolerant of other people’s views—more arrogant—than Ernest? Unless it was Ezra Pound. Unless it was Gertrude Stein.

Dick Rodgers had a genius for the melodies of love and tenderness. But you’d have been well advised not to try to buck him in a business transaction—or in a production. The same goes for Oscar Hammerstein. I know of no one more arrogant or more estimable than Agnes De Mille; she has always gone her way, and it was always the right way, because she, and no one else, was the choreographer. I watched Toscanini conduct a rehearsal. He was a terror and a bully—but he had to be to get his results. When a producer informed Boris Aronson that he didn’t like the set Aronson had made for him, Boris’s response was characteristic: “That’s your problem,” he said. “I like it.” I played tennis with Chaplin years ago; what a monster of unrestrained egoism that man was on the court! Lee Strasberg sometimes wore a gentle mask; I did not trust it. “I don’t teach the Stanislavski method,” he proclaimed when backed into a corner. “I teach the Strasberg method.” Why not? It was the truth.

I respected Harold Clurman most when he was bellowing. The restrained, agreeable, easy-to-get-along-with Clurman was sometimes devious and tricky. He had an astonishing posture when he shook hands with someone who had power over him; he bowed, jutting his head forward in a sycophantic, “Near Eastern bazaar” manner. When he bellowed he stood erect, arrogant and admirable. That was his worthy self and the Clurman I respected enough to enter into a partnership with in 1946.

THE FIRST offering of the Clurman-Kazan partnership was Max Anderson’s Truckline Café, which Harold directed. I was disappointed in the production. The script when we opened was basically unchanged from what I’d first read; nothing had been done to improve it or make it more stage-worthy. Although two small parts were brilliantly played by two unknown actors (Karl Malden and Marlon Brando), the central roles were limp, in both the writing and the performance.

I’d heard Harold’s first talk to the cast; he was at his best. It was brilliant. I admired his analysis of the play and its meaning. The cast was dazzled, as were all Harold’s casts, by the man’s insights and his eloquence. But then—what had happened? Very little. The play had been an occasion for Harold to perform. When the actors, like the two I’ve mentioned, had exceptional talent, Harold turned them on to exceptional performances. But as for the rest of the show, it sunk into a slough and remained there. It was damned dull.

Despite—or along with—my disappointment, I took a perverse pleasure in the failure of the performance. That’s not a pretty confession, but it’s true. I couldn’t talk like Harold, but I sure as hell would have done something about that playscript. I’d have kept after the author until he improved his play. I wouldn’t have sat by, being brilliant and adored, while the play failed. I might even have interfered with the rights of the playwright given him by the Dramatists Guild and “fussed” with the text. Harold had said, when I’d indicated my impatience with the meager extent of Max’s rewriting, “That’s the play. You can’t do anything about it. It will succeed or fail, but that’s it.” This fatalism I found intolerable.

Truckline Café, before he was famous (Photo Credits 18.3)

Later in my time, I was to be severely scored for moving in on playwrights, but if the accusation is true, I’ve never regretted it. Too many people’s hopes hang on the outcome of a play’s production to allow above-it-all behavior. When I’ve felt strongly, I’ve urged strongly. “You don’t like it?” I’ve warned playwrights. “Then don’t work with me.” I simply couldn’t stand by and wait to see how things would turn out. (There, incidentally, is the third quality necessary for a man working in the arts: vain, arrogant, and unyielding.) I have never regretted this way of mine. When the plays were right at first reading, like Death of a Salesman, A Streetcar Named Desire, and Tea and Sympathy, I’ve asked for no changes.

One thing was clear to me after Truckline Café: We needed our kind of actors to play the leading roles in our productions. The central parts in both Sam’s and Max’s plays had been inadequately performed. It was time to embark on the half-hope, half-plan I’d had in Manila the year before; it was time to try to produce the actors we needed for our theatre.

There have been foolish debates as to who first thought of the Actors Studio—as if there were some merit in conceiving the idea, when the merit consists in getting it going. Since the debate continues, I’ll settle it. I thought of it first, that night in Manila. When I got back, I’d waited for the right moment. This was certainly that moment.

I spoke to Harold Clurman about it first, in general terms, saying that we certainly did need a better corps of actors for the plays we were likely to be doing and that I’d thought of starting a small studio for training young actors. His response was: “I’ll speak to Stella about it.” That concluded the discussion for me. I like Stella Adler now, but at that time her name recalled my humiliation during Casey Jones and the resentment I’d felt when Harold brought her in to “coach” the young actress I was directing. I didn’t speak to Harold about my studio idea again.

I had another notion. All through my time in the Group, one of my close friends had been Bobby Lewis. Directly after the Group stopped work, Bobby and I had planned a theatre together. We hoped to make it a people’s theatre and have a dollar top admission price (believe it or not). We even thought to call it the Dollar Top Theatre. Molly was involved, to find and prepare plays. Irwin Shaw responded to our enthusiasm by writing a play for us, its title burdened with a premonition: Labor for the Wind. Bobby had worked devotedly; I was impressed with how well organized he was. But even as we made our plans, the rising costs of production made a dollar admission price impossible.

This failure did not sour our relationship. Bobby, I believed, was the ideal man to start a studio for actors with me. It never occurred to me to involve Lee Strasberg. I had the same problem with him that I had with Harold: They’d both been my boss. Also, Bobby’s teaching had characteristics Lee’s did not have: simplicity, clarity, and a sense of humor. Bobby stressed the bolder, imaginative side of acting, rather than emphasizing the interior emotional event.

Walking with Bobby in Central Park, I told him what I had in mind. Without an instant’s hesitation, he responded enthusiastically. We made our plans that very day: There’d be two classes, Bobby taking the more experienced players, I the beginners. In the days that followed, we went over the names of actors to invite, called some of them in and discussed our project with them. We decided there’d be no tuition charge and agreed to work without compensation ourselves. The only qualification for membership would be talent. No one would buy his way in. Our goals were modest, our principles clean. Over forty years, they have never been altered.

We needed an administrator who’d know what we were up to and not wish to convert a free studio into a money-making proposition. We both thought of the same person: Cheryl Crawford. She responded eagerly and was to do much more than administrate. Cheryl has never disappointed me.

Bobby did. He quit the Studio after the first year, for reasons I thought absurd. Cheryl and I replaced him with a series of teachers, all good people, but none of them wished—or were wanted by us—to be completely involved in what we were trying to do. During the three years we were looking for the right person, I kept my classes going. I knew if I dropped out the Studio would collapse. But it had become evident to me that I didn’t really enjoy teaching and was no good when I forced myself to it. I remember the day I told Cheryl that it was not only a matter of finding a replacement for Bobby; we had to find someone I could “give the Studio to.”

We came to believe that Lee Strasberg was our man—if we could seduce him to come with us. He’d resisted every reach, again and again, possibly because he resented that I hadn’t turned to him first. After all, he’d been Bobby’s teacher. Perhaps what finally brought Lee to us was the failure of his Peer Gynt with Julie Garfield, a production he’d been planning for many years. This disaster, capping a series of other setbacks for Lee in the commercial theatre, made him ready to come with us. Once he did, no one could have been more committed or more devoted. Or more valued by everyone there. Over the years, respect became hero worship, and hero worship idolatry.