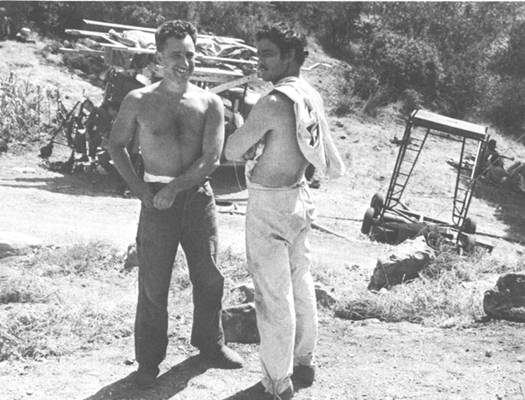

Brando on location (Photo Credits 24.1)

I HAD a nickname for her, “Noble Day.” Noble is noble, which she was. Day was her middle name. She came from an old New England family, the Days. If you saw Life with Father, the obdurate fellow presiding over the dining room table was a Day. Molly’s great-grandfather had been president of Yale University, and he’d kept the students in line. The other half of her father’s family chart showed a succession of Thachers. They were from New Haven too, didn’t live in doubt, and were known for going their own way. Mix the two together and you have Alfred Beaumont Thacher, her father, and you have her: granite. Her maternal grandfather was of unrelieved German stock, the head of the herd, an industrious man who made more money than he needed and gave the city of Cincinnati its zoo. It’s still there, carrying his name, Erkenbrecher, which means what you think it means, earth-breaker.

Quite a load for a gentle girl to carry.

The Days and the Thachers had a family motto, although they didn’t know it. I gave it to them. “There’s a right way and a wrong way and nothing in between.” The Days and the Thachers prided themselves on their plain talk. They had no reason not to be plain, since their parents and uncles and cousins ran the community; they were its judges and its public authorities. The Erkenbrechers were known for their pertinacity. Like the Days and the Thachers, the Erkenbrechers had ramrods up their asses—although their backbones didn’t need stiffening. Molly never learned to compromise. Why should she have? She had it all, from the first day. I envied her firmness; other times it drove me nuts.

I assume you’re making the inevitable comparisons with my people.

Of course, Molly should not have married me. Her mother knew it. But that ill mating had a meaning for Molly. Among the other people she disapproved of were her own. In the end, I liked her mother more than she did. Molly was determined to break from her family and its tradition. Enter Elia. That did it. She also wanted to tear down the culture into which she’d been born. She became associate editor of New Theatre, a Communist-front magazine, taught playwriting at the Theatre Union, closed ranks with Odets and Albert Maltz. Marrying me was an act of defiance, directed at her own kind.

I should not have married at all. At twenty-four, I wasn’t ready for it. It would be almost half a century after we married before I was ready. By then Molly was dead.

I married her because I was anxious about my worth—I suppose that was it—and she was elected to reassure me. I also married her because I loved her. I’ve always loved her. I still do. But our life together was, among other things, impossible. I couldn’t even work with her on how to arrange the furniture in our apartment. There was a right way to do this, and she knew what it was. I got into a bad habit; I’d say, “You arrange it, I’ll accommodate myself.” When she did that, I resented it. And her. The only room I’d insist on fixing for myself was my study, but when we had enough money to build a studio in the country, she planned my workroom with an architect. It was on a rather grandiose scale, and I saw what she wished I was. She was ambitious for me; that is to say, I was part of her ambition.

But I was not what she liked to think me. I’m not a powerman, to sit behind a desk, defended by a brace of secretaries, or to stride down a corridor, assistants at my elbows, dictating orders. I am not an office animal. Molly liked to run things. At Vassar she ran the college newspaper and did it well. She transferred her inclinations to me, wanted me to be a “top guy.” But I didn’t want to be obligated to lay down the law for a gang of theatre or film people. The older I got, the less I liked groups. Every time a film closed down, I was relieved—I could go my own way again. If I’d had a choice during my “big days,” I believe I’d have chosen to disappear. As I have now. I’ve vanished, people tell me. Where? Into myself. Into this book, for instance.

Then why did I marry? And why Molly? It’s a long story, but I’ll simplify it. Everything in my early life gave me a sense of worthlessness. (Relax, reader, I don’t want your pity.) My foreignness. My looks—or what I thought of them. The mumps at fourteen and what resulted. My father’s opinion of me and his disappointment, the boys in school pushing me outside their society, the girls whom everyone else was “taking out” and their indifference to me. At Williams I was not invited to join a fraternity, at the Yale Drama School I showed no talent, and none as an actor to the directors of the Group during that first unsuccessful summer. I finally had to believe what Harold Clurman believed: that I had no gift except an excess of energy, therefore no future with the Group or anywhere else.

On all these particulars Molly set out to reassure me. She was the first person who saw artistic potential in me; she not only stood behind me, she pushed me forward. She was sure I had a great talent; when events proved that I did have some, she became my talisman of success. She made me feel I could get to the top of a profession in the performing arts. With her help! And along with all that, she couldn’t wait to get in bed with me.

This was a blessing and a miracle. But when you admit another to that position in your life, you give that person power over you and, naturally, resent her. The sympathy itself is humiliating. Oh, pity the sweet, earnest, compliant, hard-working little Greek boy (with the beautiful brown eyes!). “Help me, help me!” he cries. So she did; she guided me and told me what was right and what was wrong. I began to resent that she was so positive about what I should be and do. And too often right. In time I wearied of arguing with her, let her have her way, then got mad at her for taking it. Anger was the genesis of revenge, the kind of revenge men take on their wives.

So at home I had a guide, a critic, a mentor, a constant adviser, as well as a wife. It was something I’d encouraged at the beginning, but I hadn’t anticipated how far it would go. I began to feel her guidelines as constraints. “Will you stop telling me what to do!” Those angry words, hurled at her in a loud voice, were heard often in our home. Then I began to let her criticisms pass in silence, and silence is dangerous; it’s a threat. But she didn’t see that. She kept right on doing what was “right.”

She wanted a regular, well-controlled domestic life. She’d revolted against her parents’ way of life, but in the end, that was precisely how she tried to organize our life. Dinner at seven, properly served by a “domestic” to a discriminating bourgeois couple and their four properly brought up children. I noticed that our eldest boy began to slip out of the house before dinner. He was loosening bonds too. Molly could never accept the proposition that some disorder is inevitable in life, even preferable. She wanted a firmly controlled existence; perhaps it quieted her own uncertainties, so she insisted on it.

Increasingly I wanted a less ordered life. She feared what she could not prepare for; it threw her into a panic. But I’d hardly lived yet; all I’d done was work. I longed for what I’d not experienced—which was most everything! Domesticity was her reassurance; she wanted uniform silverware with our initials on it. Nothing I’d seen of the world told me that relationships endure except by slow, gentle dissolution. They endure by shrinking; then there’s no conflict.

Still we loved each other; two fucked-up people clung together and produced four excellent children. There’s a piece of her in each of the four, and in each it’s the better piece. Our bond endured through hell’s fire, the one I lit.

I wanted everything I could get and went after it. When she withheld her approval—or when I thought she did or might or would—I resented her. After a time even her esteem alienated me; I didn’t want to have the qualities she praised me for possessing. Anger fired revenge, and the revenge was always a woman who liked me for what Molly disapproved of. I would seem perfect to the newcomer and I’d enjoy that and contrast it to the critical stance of my wife. But since I was the same man, the others soon developed the same reservations about me that Molly had. For a time they’d be reticent about expressing their criticism; there’s always a mini-honeymoon in these affairs. Then the same relationship would recur—with a different person.

All that sounds sick, and it was. But there was a true side to the struggle, which I cannot discount. People make fun of the male crisis at forty-five. I had that crisis all my life. I knew there was more to life than I was getting, and I didn’t want to miss out on anything. People forget that we only live once; I knew it from the day I was born. Every new girl was an adventure and an education, a friend in need, someone from whom I benefited in many ways. I even believed that my infidelities were an effort to continue with my wife, to “save the marriage.” It was the only way I could go on with her. As I say, I should not have married. But I wanted that too.

Did she know about these other relationships? Some of them, yes. There were violent scenes, and sometimes I’d break off with whoever it was and sometimes pretend to. Molly started divorce proceedings twice, calling in an expensive “Wall Street” lawyer from her father’s old firm. Then suddenly she jerked the legal rug out from under her counselor and called the whole thing off. I believe she finally came to accept me as I was—that is, as I’d become. We recognized certain limitations in each other. One thing she knew for sure, I do believe, was that I’d never leave her. And I didn’t, not ever. Perhaps that is the most we can hope to be sure of from one another.

Have I explained what I set out to explain? I doubt it. I shouldn’t have tried.

WHAT brought our conflicts into the open was Molly’s compulsion to tell the authors whose plays I was directing what was wrong with their work and how they should fix it. She did this carefully, earnestly, and with the greatest sympathy, but I could see that these men, increasingly, pulled away from her, resented her advice, and rejected her suggestions. The bad word, of course, is “should”; “should” is the word that would kill her. Again and again I had to remind people: Molly speaks for Molly; I speak for myself.

I can recall her sitting behind a long table with Irwin Shaw, working over Bury the Dead. Irwin was a boy then and had a boy’s devotion to her. Molly would “mother” playwrights—if they’d let her—in my behalf. But Irwin didn’t show her his next play. Tennessee Williams’s talent had an element of mystery for Molly: How did he get to be that brilliant? So she handled him gingerly. But Arthur Miller was within reach, or so it seemed. Molly fed Art, listened to him, argued with him. Art respected her candor and her frankness—for a time. She was overjoyed when All My Sons won the prize it deserved, and she recognized the stature of Death of a Salesman immediately. When Art and I made a cut in the play script, she objected, and what we saw in rehearsal proved her right. After that success, Art sent her a copy of the printed play with this inscription: “To Molly, for in effect saving it.”

When I returned home after the scuttling of The Hook, Molly told me about certain frantic (her word) phone calls from Miller, three of them at least, she said, ones he’d made to her before he called me out of the budget meeting to notify me he was withdrawing his screenplay. She said he sounded like a very nervous man when he described the encounter with Roy Brewer. Art felt sure, he told her, that they would stop The Hook from being made, do it by hauling him up for questioning. “They will ask me,” he told Molly, “if I was a member of—” Then he stopped short, Molly said, and there was a pause before he completed the sentence. “A member of the Waldorf Peace Conference,” Art continued, “and I would have to say, ‘Yes, I was,’ and that would finish me.” He sounded panicked, Molly said. Art had explained his concern to her, and she’d agreed with him that The Hook was dangerous to do at that time. “Better not expose yourself,” she said. Perhaps if she’d liked the script, she might have felt differently.

Molly wondered why Art had been quite that shaky. She was curious about his life at home and bugged me with questions. I kept mum, never mentioned Marilyn, didn’t tell Molly that I’d introduced them and how Art had fallen for the girl and she for him. I didn’t want to open that area to inquiry. But Molly knew there was something wrong. She saw before I did that Art and Mary were going to break up.

I RETURNED to California on a weekend from my scouting along the Texas-Mexico border, having decided on the locations I wanted. I had an empty Sunday—a disaster in Los Angeles—and dropped in on Marilyn to say goodbye, for I was about to leave that part of the world for many months. We vowed we’d always be good friends, a pledge that didn’t hold up after she married Miller and became Lee Strasberg’s household pet. Among other things, she told me she was pregnant and seemed rather pleased about it. “Don’t you worry,” she said. I guess she meant that she’d had abortions before and knew where to go. But I did worry; it scared hell out of me. I knew she dearly wanted a child and women were becoming single parents. Like any other louse, I decided to call a halt to my carrying on, a resolve that didn’t last long.

Again that night I looked at Miller’s publicity photograph that Marilyn had placed on the shelf behind her bed. Next to it was a neat pile of letters; Art had been writing to her. She told me he was unhappy and asked me to do all I could to help him. “He needs friends now,” she said. I wondered what the hell he was writing her. I didn’t feel as friendly to him after his escape from The Hook, but I told her that of course I’d be his friend. She was so obsessed with her passion for him that she couldn’t talk about anything else. He must have been sorely tempted to remain there with her; perhaps this was another reason he’d departed so abruptly after the Roy Brewer meeting.

After I left, she wrote me letters. From Miss Bauer. One of them informed me she’d had a miscarriage. In every letter, concern about Art was expressed. “Try to cheer him up,” she wrote. “Make him believe everything isn’t hopeless.”

Art saw what was coming more clearly than I did.

I’D STARTED making notes on a film about Emiliano Zapata in 1944. It’s the first film I made from an idea that attracted me—a revolutionist fights a bloody war, gains power, then walks away—one I started and saw through to the end. I’d made three trips to Mexico, knew every stone in the province of Morelos, done years of research and study, followed by bursts of frustration and doubt. (What the hell did I really know about Mexico and Mexicans?) But I’d gone on with it for seven years. Was it worth it? The answer, if you think of the years and the work and if you insist on having it, is: “Of course not. You think I’m crazy?” On the days when the work had gone well, the answer was: “Of course it’s worth it. What else is there?”

Shooting film on a distant location is a refuge and a relief. You are in an insulated world, where everything is organized around your enthusiasms and wishes. You are protected from all challenge—at this time, from political challenge. You’re in hiding; no one can reach you. Furthermore, I was living the life I liked best, working with a crew that followed me wherever I went and, with the ease of magic and with great good nature, did whatever I dreamed up. When they found a rattlesnake coiled under a rock I’d asked them to move, they thought it funny and let it go. Overhead, vultures circled, waiting for us to leave the remains of our lunch behind. Great rainstorms rode over the flatlands; you could see them born, burst, and die. This city boy learned that if you have the gear, rain won’t harm you; you work in it. Other times the sun poured down heat until it hit the one hundreds—which made the after-work beer taste that much better. At night I had Molly and my kids waiting for me in air-conditioned motel rooms in the small, civilized city of McAllen, Texas. We dined on Mexican food, tickled our palates with hot peppers. I narcotized myself, didn’t worry about the political threat I’d left behind. I was safe out there.

The work on Panic in the Streets paid off; I’d told myself in New Orleans to pretend I was shooting a silent. Now I was able to combine the psychological technique I’d brought from the stage with clear and vivid pictures. I used many more long shots, didn’t “wing” the setups this time, carefully studied the photographs in six volumes of Archivo Casasola’s book, Historia Gráfica de la Revolución, and tried to bring them to life. I was delighted when I could create a picture that told the story without a word. I was becoming a filmmaker. As I was making this film I turned my head to the future, filled with hope and belief in myself. And I was blessed by the help of two superbly gifted actors, Marlon Brando and Tony Quinn.

Marlon delighted me. In Streetcar he’d been playing a version of himself, but in Viva Zapata! he had to create a characterization. He was playing a peasant, a man out of another world. I don’t know how he did, but he did it; his gifts go beyond his knowledge. It was more than makeup and costuming—that was easy despite Zanuck’s quibbling about his mustache. (Should it turn up or down? Was it too long or too short?) I spoke a few words of help: “A peasant does not reveal what he thinks. Things happen to him and he shows no reaction. He knows if he shows certain reactions, he’ll be marked ‘bad’ and may be killed.” And so on. But no one altogether directs Brando; you release his instinct and give it a shove in the right direction. I told him the goal we had to reach, and before I’d done talking, he’d nod and walk away. He had the idea, knew what he had to do, and was, as usual, ahead of me. His talent in those days used to fly.

It was simple for Marlon to understand that Zapata’s relationship to women was not what men in our society feel—or are supposed to feel. “Don’t be misled by all that shit in the script about how he loves his wife,” I said to him. “He has no need for a special woman. Women are to be used, knocked up, and left. The men fighting the revolution were constantly leaving them behind for months at a time. The woman he woos, Josefa, is middle-class; perhaps she represents a secret aspiration of his. She may also be some sort of idealization. There are plenty of other women available to satisfy his simpler needs. Don’t mix it up with love, as we use the word. He loves his compadres. They are ready to die for him, and he would do anything for them.” I was telling him not to play the scenes with his wife in the kind of romantic love stupor American actors pretend. For these peasants, I told Marlon, fucking is not a big deal; it’s become a big deal for us in America. But our kind of romantic love (if it is romantic, if you can call it love) is a product of our middle class. Zapata’s social concerns are his real concerns.

This wasn’t hard for Marlon to understand. He was that way in life. I’ve watched several white women (he preferred women of color) make it known to him that they were interested and available. I’ve rarely seen him respond. Perhaps this was discretion or shyness, but the warmest relations I’ve seen him involved in have been with men. What I described for the peasant Zapata was very close to the way Marlon lived his life. For both of them there were deeper needs than “romance.”

Once I saw that Marlon had found the man in himself, I gave him less and less direction. In certain scenes, I didn’t say a word. When you start giving too much direction to an actor like Brando, you are likely to throw him off the track he’s instinctively found and harm the scene. “If it isn’t broke, don’t fix it,” the saying goes. I learned from working with this man that when a director deals with a really talented actor, he has to know when to stop talking. The first thing for a director is to see what a talent does on its own. It may be, as it frequently was with Marlon, better than anything you can describe. I also learned with him to try to capture the first flight of his instinct; I “shot the rehearsal.” If you don’t get what you want, then start directing—but not until then. Above all, don’t show off how smart you are and what a brilliant director. Sometimes the best direction consists of reading an actor’s face and, when you see the right thing there, simply nodding. A few words, a touch, and a smile will do it. Then wait for a miracle. With Marlon it often happened.

I believe Marlon got a lot from his contact with Tony Quinn. It took time, but a true friendship developed out of an intense competition: Who was most macho? I didn’t discourage this competition. Marlon had turned out to be a fine rider, but Quinn dominated a horse, caballero style; he overwhelmed the animal. He was not sitting up there hoping the horse would forgive him for taking him away from his feed box. The animal Quinn saddled respected him. Tony damned well saw to that! The horse was macho, but Tony was more macho. I think Marlon noticed this and admired it.

Tony was half-Mexican, and Mexicans, even half-Mexicans, are a suspicious and jealous people. He said to me one day, “You son of a bitch, why do you give Brando more direction than you give me?” “I hardly talk to him,” I answered. “You’re always talking to him,” Tony said. “You don’t talk to me!” I knew I had to take charge right there; it was early in our schedule, and Tony had to know who was boss. “Tony,” I said, “that’s a lot of shit! So you eat it!” His face went white, and he was furious, dangerously so. For a day, he remained in an intense sulk. Then I said to him, “Tony, haven’t you yet noticed I hardly talk to Marlon?” “I see that,” Tony said, “but he’s still your favorite.” “I don’t have favorites, Tony,” I said. “I think a lot of you too.” But he remained sulky and I worried.

(Photo Credits 24.2)

So I went to Marlon and told him that Tony was resentful of me and why, and asked him to do something about it. He did. He chummed up to Quinn and they began to hang out together and go swimming in the river after we were through work. I waited up for them like a mother, watching the clock, anxious that they shouldn’t turn an ankle on an underwater branch. Only when I’d heard them come back to their quarters did I sleep easy. Soon they were close friends, as I became theirs.

The most memorable piece of directorial “business” in the film was suggested by Tony. It is the scene where he wants to call the people together to rescue his brother, whom the police are taking to detention. Tony picked up two small stones and began to beat them together. Then others near him did the same, and soon everybody in the area was doing it. Tony had heard about this peasant telegraph when he was a boy growing up in that country. The people, called together, gathered and rescued their leader. It was a specific for Zapata’s country.

During our time in Roma, Texas, I came to love the Mexican people who’d settled there, and forgot all about their country’s official censor and Department of Defense. I put many of them, particularly the women, to work in the film. As I got to know these muchachas, I realized they were like the photographs I’d seen of Greek peasant women, and I began to think of making a film in Greece. I compared them to the women in Giotto’s paintings tending the body of Christ. My favorite scene in the film is one without either of my stars. It takes place at the end of the story, in the town square on a hot day, with the sun beating straight down. The women are hardly visible, because they sit against the side of the buildings that bind the square, in the strip of shade. They are not seen clearly because they wear black, and the shadow they sit in is black. A troop of horsemen rides up and dumps the body of the murdered Zapata on a cistern top in the middle of the square. It is hollow underneath, and the corpse makes a heavy, thudding sound. One feels the weight of the body from that sound and remembers how much potency was once there. The horsemen ride off. The women don’t move from where they are, almost invisible in the black shadows. The impression is that they’ve many times before seen one of their best men dead. Their memories are full of the death of heroes who, having protested unjust conditions, have paid with their lives. Slowly, the women move out of the black to the body of their hero. They wash and compose it as they might have the body of their Lord. I kept the camera respectfully back. Since it is not close and since what it shows is not altogether explicit, the imagination of the viewer is free. The reason I tell about this scene here is that it meant to me that I’d at last moved past the stage and its techniques, to become a filmmaker.

Molly was happy all through the time I was making this picture, despite the heat that kept her in the air-conditioned motel room most of the day. This was because I came home every night needing her, and we were together. The children were rather bored, because it was too hot during the day for them to go out and play.

Molly did a beautiful thing for me. Zanuck would send me wires almost daily. In the beginning they were laudatory and appreciative, but soon there were hints that I was falling behind schedule, then more than hints: complaints and bitter ones. Abruptly the telegrams stopped. It was a relief not to read a scolding after a long day spent broiling under the sun. When I’d finished my work on location, Molly handed me a sheaf of yellow paper, telegrams Darryl had sent. She’d kept them back so I wouldn’t be troubled.

Nick and Katie (Photo Credits 24.3)

FAR FROM what is thought of as civilization, I’d heard nothing about the Communist hunt or what my own prospects were. Nor did I have a word from either Jack Warner or Charlie Feldman to inform me what was delaying the release of A Streetcar Named Desire. Having finished what I had to do on location, I came back to California to make some final scenes at Fox’s Malibu ranch. It was on the very first morning I was in my office that I heard about the death of Joe Bromberg.

It’s been said that the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) killed Joe. Certainly the pressure he was subjected to shoved him over the brink. I’d also heard, upon my return to California, of the death of a fine actress, Mady Christians. After a succession of rejections “for mysterious reasons,” she died of a cerebral hemorrhage. It was beginning to happen. A terrible threat was in the air and moving closer—as it does before a great thunderstorm when, with the day darkening, the clouds not gray but black, lightning bolts thrust through the heavy overcast and no one can be sure where they will strike next. I was eager to be in New York, not California. Let it come, I felt; I can’t stop it anyway. One thing that did help me was my determination that, while I would tell the whole truth about myself, I would refuse to name any of my old friends.

It was at this time that I became aware of the similarity of the Catholic Church to the Communist Party, particularly in the “underground” nature of their operation. I had just returned to California, was having my first lunch in the Fox commissary, and found myself sitting next to Jason Joy, Darryl’s liaison with the Breen Office. With him was one of Breen’s lieutenants, and at that luncheon I learned for the first time that Streetcar was having trouble, as Darryl had warned me it would, with the Legion of Decency, the censorship agency of the Roman Catholic Church. Warners’ New York sales manager, who’d booked the film into Radio City Music Hall, had put in a frantic call to Jack Warner, asking that someone be rushed east to deal with the Legion’s people. Warner had then consulted with the industry’s own censorship board, and in due course, Jack Vizzard, one of Breen’s best, had been dispatched to New York. I knew Vizzard well, having dealt with him on another film.

I wanted to put myself on the record, so I wrote Jack Warner, stating my concerns accurately and in a calm manner. “I recall,” I wrote, “that Vizzard was trained for the priesthood: he is certainly the most conservative and squeamish of Joe Breen’s people. The person representing us with the Legion of Decency should have a hearty respect for our picture. In personal conversation with me, Vizzard characterized Streetcar as ‘sordid and morbid.’ I would say that he was not the best person to defend it.”

My impulse was to rush to New York and defend the film myself, but there was no way I could, since I was still shooting the last scenes of Zapata. Anxiously, I made further inquiries. Feldman was in New York, and I finally got him on the phone. He said yes, there was a threat of a “C” rating, but their objections were not serious and to leave it to him. This was not reassuring. A few days later I heard that the Radio City booking had been canceled. Clearly this was because of the Legion of Decency’s threat of a “C”—“Condemned.” None of this information was forwarded to me; I had to dig it up by penetrating the institutionalized silence of everyone at Warners.

The composer for Zapata was Alex North, who’d written the music for Streetcar. He’d become very friendly with my cutter, David Weisbart, and was living in his home. He came to me and revealed that David had been dispatched to New York by Jack Warner, and the last instruction David had had from Warner was, “Above all, don’t tell Kazan you’re going to New York City.” Possibly to make David’s trip seem innocent, his wife, Gladys, had been sent with him. “They’re at the Sherry,” Alex North told me.

I immediately called Weisbart in New York. He told me he was not there on Streetcar business. Of course, this was a lie. Then he added, “Although it might develop into that.” He then stumbled about and finally said that nothing had happened so far, but something might.… And so on. I was embarrassed for him; I was making him lie to me, I knew. I was angry at Warner for having put this decent if weak man into that position. The conversation continued, full of innuendos and evasions; clearly David had been instructed not to tell me anything. Did he expect me to believe that he didn’t know what the hell he was doing in New York?

I called Feldman again. He said he was sick of the whole matter and was leaving for Europe, so dumping the problem in Jack Warner’s lap. I tried to get Warner on the phone, couldn’t, but did talk to his right-hand man, Steve Trilling. Steve was a man I’d always found honest in a position where it was almost impossible to be honest. He confessed to me that the Legion had seen the film and was going to condemn it. What changes did they want? Steve wouldn’t specify, quoting Charlie Feldman that there was “nothing to worry about.” I told him that I was furious that all this had happened behind my back, that any changes were plenty to worry about, and that I didn’t want any meddling by the Legion into the body of my film. I said I should have been told about it all immediately, and what might seem minor to Jack and Charlie would not seem minor to me or to Williams. Perhaps in response to my anger, he finally confessed that the Legion had asked for another showing, that this was serious, and what they wanted was this: “We must make the audience believe that Stella and Stanley will never again be happy together.” Which was contrary to Tennessee’s intention and his goal of “fidelity.”

My patience was undone. I’d finished all the scenes of Zapata, so I asked Darryl if I could go to New York and see if I could prevent this disaster. I told him again that Warner had promised me that the film would open in New York as I’d left it, and that we’d shaken hands on it. Darryl’s answer was a smirk; I promised I’d come back as soon as I could. My absence didn’t bother Darryl, who enjoyed editing more than any other part of the work—especially if the director was not present. I left my Zapata with him.

In New York I went straight to the Sherry Netherland Hotel, where David was staying, and demanded to know what had happened. He told me with the greatest embarrassment that cuts had already been made in the film, by order of Jack Warner and following a schedule of changes drawn up by Martin Quigley. Quigley was the publisher of several motion picture trade papers. He was a Roman Catholic, a “Knight of the Church,” and an honored personal friend of Cardinal Spellman of New York. I happened to know that Quigley had written the code for the industry’s Breen Office, which was, presumably, a nondenominational agency, serving the industry as a whole. Now Jack Warner had brought Quigley in to suggest what would enable Streetcar to avoid a “C” rating. I asked to see the film as Quigley had “fixed” it. It would take a few days to get the film ready to show me, David said. In other words, Jack Warner had instructed him to delay showing me my film.

I asked Quigley for a meeting. He was a large man with a fleshy face and a conference-room complexion. He stood when he talked, arms hanging loose, fingers entwined in front of his abdomen. He had complete confidence in his position and power, so had no need for overstress. He spoke proudly of having had lunch with Cardinal Spellman, whose devotion he was honored to have. Could one topic of their luncheon conversation have been Streetcar? Could it not have been? I told Quigley that his involvement in the matter of my film must not have been comfortable for him since it was secretive and, in fact, conspiratorial. He agreed to the first characterization but not the second. He told me that his presence in the issue was at the invitation of Warner Brothers, who’d found themselves with a picture that was headed for a “Condemned” classification by the Legion of Decency and—he stressed this—a mutilation or a refusal of a permit for exhibition by several censor boards operating under legal statutes in the various states. “I sought to indicate,” he said, “the minimum alterations I considered necessary to avoid the gravely undesirable consequences I have noted and to plan the proposed changes in a manner which sought the least possible invasion of the artistic integrity of the picture.” Then he said something that shocked me. “From this [what he’d said] you will see that you are really not in a position to ask anything from me. I simply made an honest and careful recommendation.” How clever, I thought.

I said I’d see the film—and, finally, I did. There seemed to be a dozen trims, whose general intent was to change the story of Stella, Blanche’s sister and Stanley’s wife, so that it was now—again quoting Quigley—“about a decent girl who is attracted to her husband the way any ‘decent’ girl might be.” There was a brilliant close-up—I’m speaking of Kim Hunter’s performance, not my direction—of her coming down the stairs to her husband when he’s called desperately for her to come back. This close-up had been cut short and with it the piece of music Alex North had written. The shot and the music were both considered “too carnal.” Other lines that were cut hurt the film, but what was hurting me was the arrogance of what had been done, as well as this: The Church people felt unembarrassed about it. There seemed to be nothing I could do. Who owned the film? Warner Brothers owned the film. Money was talking.

But I had to do something. I asked to meet with Quigley again. “Don’t you think, Mr. Quigley,” I said, “that I should have been asked to consult on this?” I knew his answer before he gave it to me. “Do you really believe that in our situation that would have helped?” The plain fact was—and I had to recognize it—the picture had been taken away from me, secretly, skillfully, without a raised voice. I discovered I had no rights. I was out. Now congenial, Quigley pleaded with me to be sympathetic to the “complicated position of your friend David Weisbart. He was strictly enjoined by his superiors to secrecy. He frequently expressed himself as devoted to you personally and as an ardent admirer of your professional talent. He contributed painstaking and skillful effort to the technical job that seemed necessary to be done.” And so on. Quigley was out to make peace.

I wouldn’t go for it. I said I resented the secrecy with which the whole matter had been masked and resented the cuts, which came from the superimposition of one set of moral values over another, that of the author and me. How can you seek to enforce, I asked, an ethical position which is that of your Church on the entire population of this country? His answer amazed me; I’ve never forgotten it as an expression of pride in power. “The American constitutional guarantees of freedom of expression are not a one-way street,” he said. “I have the same right to say that moral considerations have a precedence over artistic considerations as you have to deny it.” “But whose moral standards are you talking about?” I asked. His answer was: “I refer to the long-prevailing standards of morality of the Western world, based on the Ten Commandments—nothing, you see, that I can boast of inventing or dreaming up.”

The absolute confidence of the man amazed me. He had no doubts about what he’d done. He felt he’d saved Streetcar for Warner Brothers. He told me that originally Father Masterson, the priest who was head of the Legion, had said that Quigley’s task was impossible and that when he’d shown Masterson what he’d done, the priest had asked for more eliminations. Quigley boasted that he’d succeeded in gentling Father Masterson away from these requests. All the while, behind the scenes, a possible action by the Catholic War Veterans was being hinted at, as well as the possibility of boycotts—of the theatres that showed the film and of all Warner Brothers product.

The phrase Quigley repeated over and over was: “the preeminence of the moral order over artistic considerations.” When I said that Williams had his own morality, that he was and his film was an example of art serving a strong personal morality, Quigley smiled faintly. I saw that he felt sorry for me.

In desperation, I made two requests of Jack Warner—who was now posing as a victim of the Catholic hierarchy. One suggestion was that two films be exhibited in New York. Since the Catholic population of the country amounted to about twenty percent, the film as “corrected” by Quigley and the Legion should be shown in a theatre twenty percent the size of the big “chair factories,” and that the film as I had left it, and as the author wanted it, be shown in a large theatre, one to which Catholics would be forbidden admission by their Church. Priests, I suggested, could be stationed in the lobby to write down the names of parishioners who defied the Church’s interdiction. Of course, this suggestion was rejected as foolish and uncommercial—as I knew it would be.

Then I made another suggestion, and I saw no reason why it could not be granted both by Warners and by the Legion of Decency. I asked that since the film was being sent to the Venice Film Festival, the version shown there should be the film Williams and I had made. This was also refused. The response was that if the film was ever shown anywhere, even once, it would immediately be given a Condemned rating. The Church wanted its moral standards to be those of the world.

That was, I thought, the limit of my power. I was the victim of a hostile conspiracy. I don’t know what else to call it. I had no recourse except—I recalled our struggle inside the Directors Guild—to throw light on the matter. Possibly anticipating that I might make myself heard, Warner sent word to me through Steve Trilling. Quote: “Tell Kazan not to be vindictive.” Well, I would be vindictive. I’d be heard. I’d raise my voice. I’d throw the issue out to the people—as Joe Mankiewicz, on a smaller scale, had done. The least it could do was give me satisfaction. I was choking to death with this requirement of silence. The thing I could least tolerate was all the gentility and friendship from the men who were mauling my film.

I told Darryl that I was going to write an article for The New York Times and expose everything that had happened, so that people who loved movies would know what went on behind their backs. Darryl shrugged. “It may help your business,” he said. “But those people don’t change. You cannot persuade them to change. And if you don’t have them, you’ll have someone else.” He didn’t encourage me.

I believe that it was Darryl who let Charlie Feldman, just back from Europe, know what I was thinking of. Charlie waited until the film had opened, then he sent me the following wire, a perfect self-portrait. “Dear Gadg: In view of the wonderful press on Streetcar and everyone’s belief you will win award, I sincerely feel you are hurting yourself by issuing statements regarding cutting, etc. But in any case, as personal favor to me, would you please not make any additional criticisms for they only hurt prestige of picture as public will feel they are getting mutilated version and probably stay away. Bear in mind that everyone who has seen the picture including critics love it as it is and have attested to its artistry. In last analysis, I repeat, you are hurting yourself and, of course, hurting me immeasurably. Would appreciate your consideration this wise but if you decide to do otherwise, I guess I will try to understand. Best always. Charlie.” Charlie was such a nice guy!

The New York Times film critic, Bosley Crowther, a Catholic who’d liked the film and said so, asked me for my comments. I told him I’d prefer to write an article for his paper. I wrote what I had to say and showed it to Molly for her reaction. “Do you mind,” she said, “if I work this over a little?” I said, “Of course not” (a lie). But she was proud of me for deciding to speak up. She showed me her revised version; I admitted it was probably better. The Sunday Times printed it, and everyone in town was talking about it. I’d really thrown a floodlight on the matter; I was pleased with myself.

But I didn’t see the implications of what had happened. The Legion of Decency had acted with a boldness and an openness that were unusual for them. What it meant—and I didn’t immediately recognize this—was that the strength and confidence of the right in the entertainment world was growing stronger. Jack Warner had been deathly afraid of the Church; they could kill his business. After Charlie Feldman read the piece in the Times, he wired me again, again at excessive length, to warn me to accept what had happened with grace, since Jack Warner was powerful and could turn against me. I ignored Feldman’s warning. The next time I ran into Jack, he was as friendly as ever. I realized you can’t insult these people: There’s no concern with morality there; only business. Streetcar made a bundle—that defined me to Jack. Not long afterward, Jack and I made a deal, highly favorable to me, to produce another film at his studio. And that was that.

I WAS glad Molly approved of what I’d done; I couldn’t take any more disapproval from her. We weren’t leading a regular domestic life; I wasn’t coming home from work every afternoon, so she was frequently in a dither of nerves and attacking me for one reason or another, any reason would do. The nights were worse than the days; our bedroom was a prison. Molly’s anger at me contested with her ingrained sense of fairness, which prevented her from expressing all that she felt. A tense silence prevailed. Of course, I had no one to blame but myself. Unless it was her. I was fed up with the strains between us and longed for another mood in my life: carelessness, relaxation, pleasure, joy, a haphazard life with no responsibilities.

Bone-tired, I was an easy mark for depression. Those unspoken accusations coming at me from all sides, were they real or imagined? It seemed that I’d been under general attack for as long as I could remember. One night I had a nightmare: More cuts were being made in Streetcar behind my back, and I was struggling to save my film. I heard hoarse shouting in my sleep; it was my own. I was suddenly short of breath, then stopped breathing altogether. I understood how a person could die in his sleep from a failure of the heart. In the morning I wanted to get off the battleground and let others do the fighting. But of course they were my battles, and no one cared about them but me. Besides, I had to stay where I was and prepare myself for the political confrontation I knew was coming.

The article Molly had rewritten for The New York Times had made me a cultural hero again, but I felt dissatisfied with what she’d done. I thought it temperate and reasonable and balanced, whereas my feelings were intemperate, unreasonable, and probably unbalanced. I’d made the film, worked like a demon and a slave, only to be forced to submit it to the will of a proud conspiracy, led by the gluttonous Pope of Fiftieth Street and the men who worked under his guidance to win his approval—“The Powerhouse,” it was justly called. I’d had no defense or even opportunity of resistance. One thing I was sure of: There was a large and effective organization conducting its business and seeking its goals in secrecy, and it had beaten me. Despite the piece in the Times, I’d been humiliated. And it wasn’t over yet.

Now an air of dissolution settled everywhere around me. From sources I didn’t know, mysterious pressures were attacking the professional lives and, as a consequence, so it seemed, the personal relations of many of my friends, dissolving friendships, breaking marriages, voiding good resolutions once made in full faith. Chaos was in the air; all kinds of human connections were coming apart. I remembered how many of these human bonds had started with high hopes, now defiled.

During the time of my meetings with Quigley, I’d had a long talk with Art Miller. He and Mary were breaking up. What pain on both sides! Month after month he’d begged Mary to take him back, but she couldn’t bring herself to forgive her husband. Her confidence in the worth of their union had been undermined permanently, it seemed; she didn’t believe anything Art told her. He’d been doing his best, he said, to hold their marriage together, but according to him, his wife was behaving in a bitterly vengeful manner. He said their home had no warmth of love or generosity. She didn’t make the least effort to please him or make his friends welcome. Brought up Catholic, she’d renounced that faith, turned to the left, taken to psychoanalysis. Again I realized how indelibly, once the knee touches the floor, a Catholic upbringing stamps the concept of sin on its people. Art simply had to be punished—despite the fact that I believe Mary felt she’d failed in the marriage too. It was obvious to me that another woman could now take Art away.

Marilyn had from time to time been writing to me at the Actors Studio, telling me how bleak life had been since we’d left California, then going on to passionate declarations of her persisting love for Art. To my astonishment, she was becoming quite a star and was very much in demand. One day a letter informed me that she was coming to New York and Art was planning to meet her. She said she hoped I’d at least drop by her hotel, say hello, and wish her well in her quest. She did arrive, and I did drop by her room to have a few words with her. I found her obsessed with her passion for Miller, rushing down to have her hair done so that when he called, she could ask him to come right up. She hadn’t heard from him yet, and I had an uneasy feeling that she was going to be stood up. I told her I’d telephone later and did so at the end of the afternoon. She sounded desolate. Art had called, she said, and with the greatest regret canceled their date. She begged me to come up and comfort her, so I did. Her hair, which had been all trussed up by a hairdresser, was in disarray. Humiliation had torn it down. The next day she returned to California.

I knew how wounded she’d been because I’d seen how high her hopes were that morning. But my feelings, if not my sense of justice, were with Art. There is nothing more painful than pulling down a home where your children live. I’d seen our own furniture carried out the front door by moving men. I could appreciate why Art had behaved as he did.

WHILE I’d been making films, Lee had made the Actors Studio his place. He had an artistic home now, and it became his power base. He was not being paid for his work there any more than anyone else was. For his living expenses, he relied on his private classes, which were becoming famous and brought him a good living. The sessions at the Studio brought him something more: the adulation he hungered for, as well as a unique power. Lee controlled who was admitted to the Actors Studio, which, largely because of the films I was making, became known as the birthplace of stars. An actor, it was believed, could step from there directly into one of my films.

Now came Lee’s glory years. Every Tuesday and Friday at eleven in the morning, he entered a place where an eager crowd of actors was waiting for him. He sat in the front row before the acting space, with his wife, Paula, at his side. A secretary handed him a card, and Lee read off the title of the scene to be played and the actors who were to play it. His face was solemn; his intensity made everyone feel the importance of our profession. When the scene was finished, Lee questioned the performers. “What were you trying to do?” This question lifted the discussion that followed to a craft level. The actors had been made aware earlier what their special problems were and had been working to deal with them. We’d been watching an exercise in technique, not an entertainment. Having heard what the intention of the players was, Lee turned to those sitting behind him and asked, “Well, what would you say?”

Now there was great hesitation; opinions were offered fearfully. Suppose Lee didn’t agree? Suppose he took offense? We’d all been made aware of his temper. Sometimes responses were offered in a tremulous voice. An actor might preface his statement with: “As you said last time, Lee,” or “Like you always say, Lee,” followed by an observation he had reason to believe Lee would agree with. I’m not sure Lee liked this crawling, but he didn’t stop it.

After he’d heard what “the people” had to say, Lee turned his back to them, and the microphone at his side was switched on. Notebooks were opened as young actors and actresses prepared to do what I’d done a quarter of a century before: make notes of whatever Lee had to say. Every comment he made about every aspect of our craft was preserved for posterity. He was a stern and devoted father and, equally, a loving mother who assumed a near total responsibility for the welfare of her family. He was also a tribal chief leading a movement that was to change the art of acting in our theatre. His sessions had the intimacy of a family gathering but also the intimacy of a cabal. Nowhere and for no one have I seen the honor given Lee during those years. Everybody loved him then. So did I.

Responding to her need to find something somewhere that she could respect and from which she could learn, I arranged for Marilyn, when she was in New York, to be admitted to Lee’s sessions as an observer.

MY WORLD of friends was now in political as well as personal turmoil. I hadn’t seen most of my friends for months; when I did again, I found great changes, a sign, I believed, of the swelling power of the right. Its particular type of terror was about to be imposed on our little world. My old friend Kermit Bloomgarden took me aside one day and, in dire tones, gave me his advice. “You’d better come back to the theatre now,” he said, “and stay on the East Coast.” That’s all he would say. Did he know something I didn’t about what was going to happen? Or was an instinct talking? I noticed that with his pressman, Kermit was hastily building a strong public image for himself in the city. Would this protect him?

Months before, Julie Garfield had testified as I intended to, not offering names, defying the committee. Immediately well-wishers, whose number included his agents and others who had a financial stake in his well-being, were at his side to advise him that if he maintained the position he’d taken, his career in films was over. The studio heads already were afraid to employ him, and a star was becoming an unemployed actor. When I saw Julie, the impression I had was that he’d begun to look seedy and to wonder what was most important in his life. He turned to a lawyer, Louis Nizer, for advice, and I suspected that Julie’s feelings were shifting to a more “reasonable” position. His wife, Roberta, had hints of Julie’s evolving change of heart and disapproved of it. Julie told me that he was now uncomfortable in his own home, that his living room was always full of people who were scornful of him—friends of his wife. He said that when he came home he didn’t feel welcomed. He hadn’t done anything overt, but the left was alert and quick to condemn.

We had Mr. and Mrs. Fredric March to dinner one night, and drink loosened Florence’s tongue. She told us how badly Freddie had treated her—and Molly looked at me. She also spoke of how she’d constantly been forced to hold Freddie up politically. “How hard it is,” she said, “to be a mother to someone your own age!” Freddie said not a word. They’d both been under assault by a watchdog newsletter, Counterattack, which was sent to studio heads. For six months, she told us, the calls for Freddie’s services could be “counted on the fingers of one hand, with a finger or two left over.” Finally they sued Counterattack. Her husband, Florence maintained, had not been staunch in the crisis. “He was ready to take anything he could get and run,” she said. The case was finally settled out of court; one of the provisions was that the Marches file an anti-Communist statement in the newsletter. It amounted to a public humiliation. They did it, but despite the clearance, the smudge remained, and it was a while before Freddie worked again. It was a demeaning time and put a bitter barrier between the couple.

I also spent an evening with Clifford Odets, who was preparing what he would say to the committee. It would be defiant. At this time, when he needed support at home, he was breaking up with his wife, Betty. He told me the story of their relationship from the beginning and of her adventures. He said he’d been forced to tend their children as a mother. Made distraught by all this, he couldn’t write. Meantime, his funds were running low. I thought perhaps personal desperation might make him write plays again, but this proved not to be true.

I had a message at the Actors Studio: Would I please call Lillian Hellman. She told me over the phone how much she’d enjoyed her visit to my set (Panic in the Streets) and that she’d like to entertain me at dinner. A Louisiana lady, her specialty was gumbo. She was all spiffed up for my arrival, wearing not a dress but the garment known as a housecoat, zipper front. From the point of view of allure, it was unfortunate. She informed me her cook was out for the night. She’d made the gumbo herself, and it was the real thing, delicious, and there was plenty of garlic bread to mop up with and bottles of rich red wine. I felt like a young girl cornered by a rich old man who expected the reward she could afford to pay for the fine meal he was providing. I became acquainted once again with her chronic cigarette cough, which was racking-coarse, and her wit, which was the same. She made fun of the cowards who’d already buckled before the House Committee and of those who certainly would, and invited me to join in her laughter. I did, for a while. Then she scoffed at some people I liked, and I saw that her general attitude toward the world around her was derisive. She made fun of everyone she talked about, and I wearied of her. Despite all, I could detect a nervousness there, a reaching for allies. Even her laughter was nervous. I suppose what she hoped would happen with me might have some way reassured her. But I said I had to get up early for a rehearsal, thanked her for the delicious gumbo, and left. Perhaps I was abrupt, because she seemed offended. Whatever her needs were that were not satisfied that night, they were met later through the attendance of Jed Harris. Jed outdid Lillian; his entire conversation consisted of putting down everyone. What a clatter of derision there must have been when those two coupled.

I HAD a unique letter from Tennessee Williams, containing a rather desperate request. I was very close to him now, and he was asking me, in the greatest confidence, if I could arrange for a lady friend of his to be artificially inseminated. He didn’t say who the lady was, and perhaps, in this case, it didn’t matter. The point was that Tennessee, still with Frank Merlo, very happy and likely to remain so, wanted offspring. He wasn’t sure he could achieve the physical arousal necessary for him to penetrate a woman, this not from impotence but from whatever it was that had blocked him all his life. He’d had one affair with a girl, he’d told me, before he’d ever been with a man; that had been his last. The result was that he didn’t have the confidence that he could create his own child. I told him I’d look around, but when I didn’t hear any more about this from him, I forgot about it. He would die childless.

NOW, SINCE I wasn’t working, I should have had ease and time for reflection, but this proved impossible. Everything was making me anxious—the future, the past, my marriage, my character, my work, and the fates of my friends, which undoubtedly anticipated my own. I believed I’d soon be required to testify before HUAC. I also believed that after my article in The New York Times, Cardinal Spellman would press the full weight of his influence against me. I suspected then and I believe now that this church—in its upper cadre—was hand in hand with McCarthy. Spell-man was to stand up for McCarthy later, even after he’d been discredited. I could not call what had happened around A Streetcar Named Desire anything but a well-organized conspiracy.

I still felt safe in New York and in the theatre. Having convinced Tennessee that we could enlarge his short work Ten Blocks on the Camino Real into a full-length evening, I planned to do the play with actors from the Studio and with my friend Anna Sokolow doing choreography inspired by the Mexican primitive artist Posada. I set up my production office where the Studio had its quarters and engaged a secretary, Mae Reis. Tennessee came north and we began to hold readings for the cast.

Early one afternoon, Mae Reis informed me that there was a “Negro” waiting to see me. At that instant, I was on my way into our rehearsal space to hear Lili Darvas read for a part. Tennessee had preceded me, so I was in a hurry. “About casting?” I asked. “I don’t think so,” Mae replied.

He was a fine-looking black man with a kindly face and a decent smile. I said, “You want to talk to me?” He stood up and said, “Can we go somewhere?” This puzzled me, but I led him a few steps toward the entrance door, a hint that I was in a hurry. There he showed me his identification, which I didn’t read, then he took a double-folded pink sheet out of an envelope and gave it to me. “This will be a secret session,” he said, lowering the level of his voice. “You don’t tell anyone, we don’t tell anyone. We expect you to be a cooperative witness.” I said, “Thank you” (I don’t know why), took the subpoena, and hurried in to hear Miss Darvas try out for the part of Marguerite Gautier. During that afternoon, I forgot about the subpoena. I didn’t feel nervous after we stopped work. How casually, I thought, and how quickly critical events in life happen. I’d been “called”; it was over. I had a drink with Williams—a double martini for him, an old-fashioned for me—and we chatted about our casting problems.

But that night, I couldn’t sleep.