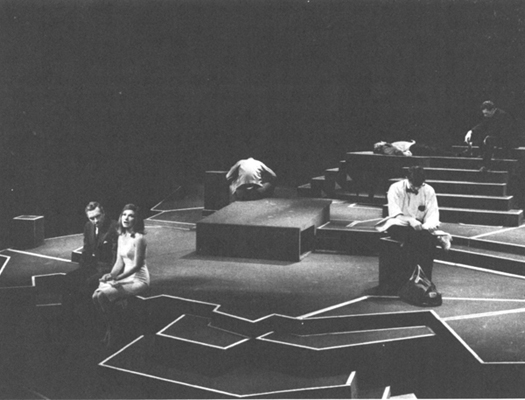

Jason Robards and Barbara in After the Fall (Photo Credits 37.1)

I DECIDED to get out from under. I rented two rooms in an apartment complex a couple of blocks from the ANTA Washington Square Theatre. No ghosts there, no sounds in the night except distant traffic. I worked on Art’s play as best I could—that is, “professionally.” I did my job. But the play needed more from its director than expert techniques.

I was alone whenever I could be, lying on the new bed downtown, an animal in a thicket, or walking here and there in the Village at night, trying to figure out what I truly wanted from what was left of my life. I could go anyplace now, live anywhere, do anything I wished. This was a shocking realization; it was also the first cheering thought I’d had. Barbara would visit me from time to time, but she found me inert and listless. “How long is this going to go on?” she’d ask. “I don’t know,” I’d answer. “This could be the new me.”

Mornings, before rehearsal, I’d sneak uptown to the apartment, pull open Molly’s filing cabinet, and look through her papers. What I found shocked me—a series of false starts on plays, aborted first acts: pages 1–9; another, pages 1–12; another, pages 1–8. On top of the cabinet were two decks of playing cards. What frustration and pain were there, what waste of a fine intelligence! Living in my memory was the spectacle of constant striving after achievement, people losing themselves, faltering, stopping, and disintegrating. Might that be my fate too? Something malignant was gripping me, which I didn’t understand but had to shake loose. I determined I would not be one of this number; I’d find a new life.

That thought—to find a new way—kept coming to me. Here I was, deeply involved in Lincoln Center and its Repertory Theatre; a good part of the fate of that effort was on my shoulders. But after Molly’s death, whenever I allowed my mind to move freely, it asked for a drastic change in my style of living. My daydreams told the truth: I must get rid of that haunted perfect apartment and live somewhere else, alone, quietly; not necessarily in this country, perhaps in Greece, where I knew the language and the people; perhaps in Paris, the city I loved best after New York. It embarrassed me to confess, but despite the impassioned speech I’d made before the first rehearsal of Art’s play, now, only five weeks later, Molly’s death had jarred something loose and I didn’t give a damn about anything happening at the Repertory Theatre or in its future. It wasn’t right, it was shameful, but obviously it was heartfelt or it wouldn’t keep coming back.

It was then, during that time of “going through the motions” at the Repertory Theatre—passing whole days without talking except when my professional duties required that I must—it was then that I decided to quit. I didn’t know it; I wouldn’t admit it, because it was disloyal to so many good people; I would have denied it vigorously if anyone—a psychoanalyst, for instance—had suggested it. But it was during those days, in my silences, that I decided to become another man, ply another trade, and live in a totally different way. It would be almost a year before this actually happened, but during those weeks after Molly’s death something pulled my old self loose from what was binding it to what it didn’t want.

AS I WAS thinking about this chapter and looking over notes and letters, I happened on Tony Kraber’s letter again, the one I’ve quoted. When I’d copied it into this manuscript and then my answer, I thought I’d finished with it. But I read it again before turning it face down on top of the pile of material for that year.

Then, a short week ago, I had a dream that surprised me. I was visiting Tony in his apartment, and all was peaceful and friendly. Tony was glad to see me and I was happy to be with him, but no special fuss was made about it; it was an everyday thing. There was nothing about this dream that made my being there and his welcome surprising. Nothing was said about my naming him to the House Committee on Un-American Activities. We were in the simplest harmony, and it felt fine.

His wife, Wilhelmina, whom I used to like, for she was a stalwart girl, was not in the room, but there was a boy there: his son, I supposed. He wore metal-rimmed glasses and looked rather frail. I don’t know what children Tony has or, if he has a son, whether the boy is anything like the person I imagined; he couldn’t be, because such an offspring would be well into his middle years now. But I saw the boy young, frail, and withdrawn—hurt. “Where’s Willy?” I asked suddenly. “She’ll be out,” Tony said. I listened for resentment in his voice, but there was none, and I was relieved. “But his wife,” I said to myself in my dream, “she must still be angry at me. And this boy, their son, he’s not well.” Then Wilhelmina came in, greeted me in a casual and friendly manner, then said a sparky “Goodbye, see you later” to her son and her husband and was gone. She’d seemed cordial to me, and I was overjoyed.

Then I half woke and knew it was the middle of the night, because my wife was sleeping beside me. I rolled her to me and she put her head on my shoulder and I thought what a terrible thing I’d done: not the political aspect of it, because maybe that was correct; but it didn’t matter now, correct or not; all that mattered was the human side of the thing. I said to myself, “You hurt another human being, a friend of yours and his family, and no ‘political aspect’ matters two shits.”

I wanted to apologize to Tony. “It’s not necessary,” he said, guessing my thought and speaking again out of my dream. That’s generous of him, I thought, just as his letter had been generous. I felt ashamed. I knew my dream was expressing a regret and a wish. What did those old politics or any politics matter to me now? “Political aspect” indeed! Did it even matter that Tony had told a lie about me? He was human and I’d hurt him, and perhaps I’d made it harder for the son whom I’d imagined and kept at that young age. I felt that no political cause was worth hurting any other human for. What good deeds were stimulated by what I’d done? What villains exposed? How is the world better for what I did? It had just been a game of power and influence, and I’d been taken in and twisted from my true self. I’d fallen for something I shouldn’t have, no matter how hard the pressure and no matter how sound my reasons. The simple fact was that I wasn’t political—not then, not now. I only wished that I could have been as generous and as decent as Tony had been with me.

As for why I’d done it, I couldn’t look at that anymore.

Then I woke all the way and had breakfast. I knew the past was past and there was nothing to do about it.

AMERICA AMERICA was given a mixed welcome in our press. International critics liked the movie. France coddled it with honors. But here, at home—mixed. My friend Walter Kerr took exception to the dubbing. Had he gone to the showing blindfolded? My pompous pal on The New York Times stammered for a few paragraphs, then said it was too long. When they don’t know what to say, they say, “Too long!” Financially it proved a disaster. I felt sorry for Ben Kalmenson at Warners, who’d “taken a bath” for me. Otherwise I didn’t care. It’s my favorite picture. Full of faults, it has virtues that are rare.

Only one reaction truly concerned me—my mother’s. I found I was surprisingly anxious about what she’d feel. There were scenes out of her girlhood nightmares, and she’d see them, not read about them. Words can be a buffer. She would see the “savages” she feared most, behaving as the Anatolian Greeks who’d lived in Turkey remembered them. Mother might fear that because of what I’d put on film, they’d revenge themselves on me. I’d never before been so wound up about what she’d think of anything I’d done. But she was the person in the world I loved most in those years; age and her recent widowhood had rendered her more vulnerable. If I hurt her, I’d wish I’d never made the film.

So I proceeded cautiously, surrounding her with the claptrap of security. I hired a limo to take her and a friend to the building in New York where people from Warner Brothers would escort her to a projection room. Then I waited. After I was sure she was back in her apartment, I called. She said very little, but seemed to be pleased. I was so relieved that I chided myself for having been so nervous. After all, art is all, I said to myself. If the film had upset her, she’d simply have had to get over it. Whatever she’d thought would not have caused her physical harm; she’d recover. Why had I worried so, why was I so relieved now? Still I rushed out to Rye to make sure she was okay.

Now, twenty-five years later, the same anxiety has surfaced again, raising the same question with reference to this autobiography: How far does a writer who uses the material of his own experience go when he knows he might cause embarrassment or humiliation to someone dear to him? I am referring to my present wife, Frances. When we were “courting,” she didn’t even know I’d been a film director. It didn’t take her long to find that out, as well as a great deal more “background” that concerned friends provided. I worry that when she reads what you’ve read, no matter what warnings she’s been given, it might upset a relationship that is now happy. I don’t know what to do. It’s another me that she’d learn about; the portrait of her husband and his past in this book is not altogether flattering.

Eileen, my secretary, after typing one of these chapters a few months ago, advised me that when the book was out I wouldn’t have a friend left in the world. That doesn’t worry me. What does is the possibility that I won’t have a family left. What I’ve written might offend some of my children. “You must remember it all happened a long time ago,” Eileen says to them. But what can I do about that? I make judgments, say what I think, expose things that other autobiographies may mask. Rousseau is my model. I wouldn’t write this book any other way. Still I know I’m taking a fearful chance. My family, my children, my grandchildren, my closest friends, mean more to me than anything else in the world.

Except what I’m writing.

SO NOW Lincoln Center. I’ve never sounded off, not a peep, about my experience there with Bob Whitehead and Art Miller or with John Rockefeller and his board. But I failed there, and I was “separated” from it, fired, or would have been, and it was a public humiliation. Although I’ve been silent about what happened, I’ve not forgotten. Bob and Art and I worked like patriots, with fanatical devotion, and for long stretches without compensation, then were treated shamefully. Especially Bob Whitehead. I haven’t forgotten what I felt. I swallowed it, but it went down hard and doesn’t lie easy. Both Bob and Art were and are exceptional men; they were not properly respected, and despite all Lincoln Center’s searching for replacements, their equals were never found. Bob and Art were kicked around by their lessers. They tolerated it for a cause. Bob, throughout the years since he was relieved of his position, has maintained a silence, which may be the only dignified way to deal with what was done to him. Now I’ll break it.

To start with, we were naive. We never faced the fact that we were not partners but employees, in a vulnerable position, without tenure. Employees have no power in a conflict. The boss has it all. Whom did we work for? Not villains, not bad men, but men out of another world, who were not capable of handling the responsibilities they were given by the men who owned the real estate and had the money. I offer as evidence George Woods, the president of the board of the Repertory Theatre.

George was the most interesting man I met at Lincoln Center. It follows that he was not what he appeared to be. I’m embarrassed to say that I liked him—I’m perverse that way—despite the fact that he became the mortal enemy of my partner, Bob Whitehead, and in time of our effort at Lincoln Center. From behind the scenes he was to supervise our removal from the Repertory Theatre.

Who was he? The chairman of the board of the First Boston Corporation, a director of the Campbell Soup Company, the Chase International Investment Corporation, the Commonwealth Oil Refining Company, Inc. (Puerto Rico), the Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India (Bombay), the Kaiser Steel Corporation, the New York Times Company, and the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company. Does that convince you that he was equipped by his experience to oversee the creation of a repertory theatre? No? It didn’t me either. Well, then, add this: He was a close friend of John Ring-ling North for many years, and a director, treasurer, and financial adviser to the “Greatest Show on Earth.” Does that help?

There was a good reason why he held positions on all those boards. He was the essential board member, one tough hombre, dressed in the WASP corporate manager’s uniform, the three-piece suit of no particular color. I’m not sure he wore the same suit every day, but I’m not sure he didn’t. His clothing was designed, chosen, and worn by him and others of his trade so as not to give warning of danger brewing as they took seats around a board table. Men of excessive wealth, like the Rockefellers, who cultivate a culture-loving and public-spirited image—“service” was their ideal, the Asia Society their hobby—need people like George to do their cutting up and paring down. George’s presence with his hatchet kept their hands clean. The man, his manners, his actions, his ultimate mystery, fascinated me even as he was “killing” us.

I understood George best by comparing him with my partner. Bob Whitehead’s family is Canadian, clean and secure, solid old-time stuff, well educated and well heeled. They own, along with other considerable interests, a good hunk of Labatt’s, a pretty good beer. They vacation on cold northern lakes and are expert light tackle fishermen, a talent only the affluent can cultivate. Bob has about him a charming air of gentility.

George Woods was charming too, but not because of gentility; he had, despite his cultivated corporate board manner, the soul of a street kid. Not everybody liked him; he was an acquired taste. I couldn’t help believing that the way George behaved was not natural to him; it had to be learned. He must have studied to dress as he did and to conduct himself in a manner that reassured the Rockefellers and their brothers-in-money because it was professionally useful. But oh, God, was he ever tough! He soon found the soft spot in Bob’s decency, his sensitivity, his basic kindness, his ultimate good nature—and perhaps his somewhat vague way with the figures on a balance sheet. Bob became George’s pet victim. The board table was George’s killing field; his eyes would tighten to focus as soon as Bob and he sat across from each other. He hounded Bob down, meeting after meeting. It seemed that he couldn’t stand the sight of Bob and his distinguished good looks. A clash of what’s called “chemistry”? That too, of course. But there was in particular a certain “fudging” Bob would retreat to when George came after him with his long knives at a board meeting. Bob would be discomfited just a little, would stumble and lose the rhythm of truth, when George thrust a direct question of costs at him. Then the smell of first blood flowing would stimulate a feeding frenzy in George, and not disguising his scorn, he’d persist until he’d finished Bob off.

But that was in the room where the board met. There was a bigger arena. It started with the incident of the ANTA Washington Square Theatre, which George had tried to block every way he could. When we went ahead with it anyway, Bob deciding here, I agreeing from somewhere behind the camera in Greece, that did it for George. I’m not sure he needed an excuse to hate anyone he chose to hate, but if he did, he had it. He would certainly never forgive the person who’d publicly, openly, and without apology defied his authority and gotten away with it. Perhaps, to see it from his side, Bob’s decision to go ahead and put up his “steel tent” seemed to George to be the kind of reckless behavior with corporate cash that only those born to wealth would indulge in. It wasn’t Rockefeller’s money, actually, but it was certainly Rockefeller’s principle of the thing. There it was, defiance! The “tent” went up, the public liked it, patronized it, and it housed one considerable hit. Everyone around town knew what George had said—“You can’t!”—and Bob, in his genteel way, had put it up anyway, for Miller and me to produce our show in. And it didn’t look half bad. It wouldn’t have done uptown, but down there, with all the scholastic freaks, it seemed appropriate. There was a gleam of triumph in Bob Whitehead’s eye, and George saw it. People don’t take oaths of vengeance anymore, but if they did, George would have, and its point would have been to destroy this gentleman from Montreal who had to be taught that you can’t be so cavalier with corporate wealth and, even more important, that you don’t fool around with George Woods, who was president of the board and the corporate watchdog over that pile of cash.

I don’t know what George thought after the popular success of After the Fall. He was quiet. People were paying good money to get in and see the show. I felt he should have been happier than he appeared to be. But no. He was waiting; he knew whom he wanted to “get,” and like any jungle animal, he knew better than to strike too soon. But I saw it coming. From the incident of the ANTA Washington Square Theatre, the issue became Who’s boss? Who has the authority, the men with the money or the men with the theatre savvy to do the job? We made a mistake. We thought it was an equal contest, one we might win. What we forgot was that we were hirelings. Money was boss. The success of After the Fall postponed an outcome that was inevitable.

THE critical response to After the Fall puzzled me. And still does. I found, when I looked back through the newspaper clippings, that Miller’s play was, on the whole, well received. The critics who tore it down were mostly the campus-based academicians who make their way by writing about other writers, making books out of other books and grading artists when they’re not grading students.

Some seemed outraged by the fact that the play dealt with the intimate history of a woman who’d become, for reasons I can’t understand, their house martyr. They berated the play and the production in defense of a certain Marilyn, whom they’d never met and wouldn’t have understood if they had. They found Miller’s portrait of Marilyn self-serving, scolded him for using her to make himself look good. If you read the play now, I believe you’d find what I did, that its “hero,” Quentin, is a bit priggish and rather pompous, while Marilyn-Maggie, despite her vengeful hysteria in the last scene, is pitiable and tragic. But suddenly she became a cause, and bright boys from every side rushed to her defense by attacking Miller. Norman Mailer wrote about her without having met her—easier to do that way—relying on the illustrations to market the book.

I was amazed, and favorably so, that after his dull first act, Art could write something as un-self-favoring, as powerful, as his portrait of this desperate girl and so unflattering to himself. On the whole the audience responded to what certain critics did not. Ticket buyers had never seen anything quite like this play and its production, and everyone without exception cheered Barbara’s performance.

We followed After the Fall with a production of Marco Millions, a minor play by Eugene O’Neill, which confirmed the critical opinion that our sights were aimed too low. Mild and undistinguished, the play offered neither new insight nor theatrical art that could not have been found in a community theatre.

Then it was my turn again, and I made our first “fatal” mistake. Sam Behrman’s But for Whom Charlie not only could have been done on Broadway but should have been done there. It desperately needed the services of stars, personalities who could carry a play because of what they were, intriguing theatrical “camps” who lived only on stage and had all the mannerisms and cunning of entertainers, not people. Our company had been populated with actors who’d served Art’s play and who were to my own taste of realistic psychological drama. To put them in Sam’s play was unfair to him—and to them. His play had to be performed as an intellectual vaudeville of quips and bright sayings; our actors wore heavy shoes. The production revealed my limitations as a director, who was clearly working outside of his range, and as the artistic leader of a theatre. I added nothing to the play of wit or charm, of the spry and the sly—nothing that was unexpected or delightful. It should have been directed by another man.

The worst of it for me was that the failure hurt Sam, a dear old man of whom I was fond, in effect demonstrating publicly that he had nothing more to say to a contemporary audience. Sam, understandably, blamed me and never spoke to me again. He retreated into a dark back room of his apartment on Park Avenue and rarely came out of it.

We followed this disastrous production with one that was worse. The Changeling might have been worth doing if we’d had the actors to bring it off and the right director. The basic fault, again, was mine. I’d chosen it, I’d asked to do it. But in the face of its problems, I was incapable. Didn’t I know who I was? Did I really believe I could do anything? Why would I want to? Did I want to be everybody except myself? Surely, whatever worth I had as a director emerged only when I had material to which I related or in which I had a strong emotional interest. As for our audience, what meaning did the play or its performance have for them? None. There was no reason for them to come to it. The critics who’d informed me again and again that I wasn’t suited to the job I held were right.

Although I tried with all my might, was as conscientious and devoted as I could be, I felt little pain when I failed so miserably. My heart had left the Repertory Theatre. After Molly’s death, I continued because it was my duty and because I felt loyal to Bob and to Art. My loyalty, however, had a negative effect. I should have admitted my alienation and urged Bob to engage another director. I was still too unsettled emotionally to work well, and I told Bob to be prepared, I was leaving my position there, but that I wouldn’t do it or talk about it until a time that was agreeable to him. Perhaps he believed I’d get over this feeling; he certainly didn’t want to be left alone on the hot seat. So I did what I’ve done often in the past, put my head down and took a beating.

There was a bitter irony to all this. I’d trained all my life to be a member of a permanent acting company. From my beginnings in the theatre, I’d made this the goal of my professional life. But when I finally won the position for which I’d prepared myself with so much reading, training, and hard work, I found that I didn’t like it. I didn’t like being in the same place every day, didn’t enjoy dealing with the same problems every day, didn’t like being the father to thirty and more actors who looked to me for guidance and leadership. With some of the actors, I found, I stood as a sort of villain; Jason Robards, for instance. I’d somehow trapped him into an effort that was “no fun,” as well as “too much work.” The very essence of a repertory theatre, rehearsing one play while performing another, then alternating in roles, wasn’t for a few of our actors what it was supposed to be. Nor was it for me.

For Barbara Loden, life with us was one unrelenting contradiction. She’d scored an immense success in After the Fall, which made her happy, but then, following her triumph, she saw me as a roadblock preventing her from reaching the stardom her talent deserved. Friends told her that after her success in the Miller play I was depriving her of an even greater success, the kind other, less talented, actresses enjoyed. Barbara would repeat this opinion to me, half giving it her support, testing me, waiting to see how I’d respond. I’d shrug.

She had her photograph as Maggie on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post. But even while that issue was being read and she was enjoying compliments, the following week’s issue came out, with someone else on the cover, and Barbara felt that she was letting her main chance slip by. The next part in which I cast her was a “bit” in Behrman’s play, three lines. Sam was delighted to have her in this tiny role; it affirmed what I’d promised him would be the value of giving his play to the Repertory Theatre. But Barbara resented the role. It diminished her. She believed she’d earned the rewards of having put over a great hit, one that had brought lines of people to the theatre every night. But I was denying her those rewards. She felt trapped.

At the same time, Barbara, like all the other actors there, was an idealist, believing that what an actress should aspire to was to be a complete theatre artist playing many roles, to be a member of a continuing artistic institution doing plays that “said” something. She’d voice these ideals frequently, throwing them back at me and pointing, as we all did, to the theatres in Russia and England. But the pride of being part of a great acting company didn’t count in this country as it did in England and Russia, partly because we were not yet a great acting company but more significantly because of what was in the American air, that speedy upward mobility, those sudden dramatic rewards for success. Barbara wanted desperately to be a movie star, at the same time that she despised Hollywood and the films it turned out.

While she believed passionately, or said she did, in the ideal that our theatre was dedicated to, the vry passion of her belief made her more disappointed and so more vehement in her criticisms of our work, especially my own, when we failed. “This is a fake,” she’d say to me. “It isn’t what you said it was going to be. I’d be better off in the movies. At least that would be honest.” “Go ahead,” I’d say, “leave. Goodbye.” But she didn’t go. “I’m a lot better than those actresses in films you used to sleep with,” she’d say. “Why shouldn’t I have what they have—a decent home, a nice car, and servants and comforts and security? I’ll never get those here, will I?” “No,” I’d say, “not what you’re talking about. Not here.” “Well, then, I’m quitting,” she’d say. But she didn’t quit.

Jason was an idealist too, but without the contradictions. He criticized us from an eminence of what a theatre should have been and could have been, but his behavior was less lofty. He hated the role in Miller’s play and said so to whoever would listen. He said I’d given him no help; in fact, according to Newsweek, he threatened publicly to “kill Kazan for putting him on stage in After the Fall and leaving him without a shred of direction.” He made similar comments to gossip columnists. My own impression was that he thought I’d given him too much direction. And also that Barbara had stolen the show and he knew it.

But he wasn’t all wrong in what he felt. Since I didn’t like the part myself, I didn’t know how to make it interesting. But, I thought, isn’t it inevitable in a repertory theatre that actors are assigned some parts that are less gratifying than those they’d like? An actor and a director had to do what they could with those parts, while continuing to behave well at all times. Jason did not. I believed his behavior shameful. He’d look at the audience while other actors, farther upstage or at his side, were playing scenes that he was supposed to be reacting to. He’d grumble openly or stare at the people out front with an expression on his face that said, more clearly than words, “Did you ever hear such shit?” Then he began to go further and bitch under his breath to the actors with whom he was playing, whispering irrelevancies, carrying on far outside the play’s dialogue, so releasing his scorn of the play, its direction, and the theatre, of everything he felt trapped in and he wished he’d never agreed to. He also encouraged some unrest backstage, nurtured a rebellious little cell based in his dressing room and dedicated to doubt and to what naughty behavior they could get away with. The thing to have done, of course, was to fire him, which he was clearly asking for, but I believed, mistakenly, that there was no one else in the company to play his role. There is always someone else. So I took the punishment. Besides, I was the fellow famous for handling actors, wasn’t I?

The irony of it all was that I understood Jason’s behavior, even had moments when I secretly sympathized with it. I wanted out, too, but concealed it. I did tell Bob, after The Changeling, that the ideal man to have held my position was Harold Clurman. Harold liked being father to a group of actors and dealing with their everyday problems; he’d had years handling Stella Adler’s tantrums. Family quarrels in the Jewish theatre were a natural thing, and for Harold they were part of the fun of it all. Furthermore, Harold had no “outside” ambitions, as I did—that is, filmmaking. So to an extent I was feeling something of what Jason felt while, at the same time, I was resentful of his behavior and trying not to make it possible for him to leave the company.

There was one encouraging development. On the male side, we had the beginning of a good acting company, perhaps ten men of talent who didn’t have the movie itch and knew they could fulfill their capabilities only in a repertory company. They were a staunch group and remained my good friends. Our next production, a worthy if not exceptional play by Miller, directed by Harold Clurman, was well played by this group of men. For the first time, we presented what was an excellent ensemble of actors playing together in an exceptional way. Watching them, I saw that there could be a repertory company in this country; given patience and time, it could work, could succeed as an artistic unit.

Our final production was Tartuffe, directed by Bill Ball, a director we “brought in” from outside our original “family.” He was Bob’s idea and recommendation, a good choice who did a good job. It was a first step toward bringing additions into our acting company, actors with the capability of performing in plays outside the contemporary realistic mode. These actors and Ball promised to add variety and depth to our company. This step also showed that Bob Whitehead, who was making the fundamental decisions by then, had taken notice of our company’s limitations and of mine and was beginning to overcome them. The production was given a good reception by the press. It should certainly have indicated that we were open to criticism, including self-criticism, and were determined and able to adjust our policies to make possible a broader program.

What we needed was what we never got: time—time to discover and analyze our mistakes and to correct them by releasing certain actors and replacing them with others more suited to what we were trying to do. This, I felt sure, could be accomplished. More difficult to arrive at was a proper program of plays and projects, but we’d learned a great deal from our mistakes there too. Perhaps most difficult of all was for me to deal ruthlessly with my own artistic and personal limitations, determine and define what use I could and could not be. In light of this, I wrote Bob a letter to be shown to the board, suggesting that we reorganize our leadership, include Art and Harold in all decisionmaking, and reconstitute ourselves as a foursome rather than a two-man partnership. This we did toward the end of our time there, and it was an effective first step. But our early mistakes and my limitations overtook us and it was, before we knew it, too late to save our theatre.

The disaster of The Changeling had destroyed our defenses, and we were now vulnerable both to our corporate bosses—George Woods and his augmented board—and to critics who were seeking to destroy us and never let up. Most of these men, Robert Brustein and Richard Gilman leading the pack, were now being attended to by the board. What they’d predicted appeared to be true, that we were mistaken choices who could not bring off what we’d undertaken. No one noted the adaptations we were beginning to make and the significance of these changes. A living sacrifice was being called for to pay for our failures.

NOW a new figure came on the scene. William Schuman, chosen to be the new president of Lincoln Center, was and is a famous composer; he’d written nine symphonies, the same number as Ludwig van Beethoven. He was very bright, wore his clothes well, and gave off the air proper to this post: Culture can be good business. He had a quick wit and knew how to arouse confidence. With some of the qualities of a hypnotist, he could influence people and solve problems. Having run the Juilliard School of Music for nine years, and there proved his competence as an administrator, he was clearly the man for the job. The top people at Lincoln Center were confident Bill Schuman could solve the crisis at the Repertory Theatre, and he shared their opinion. He saw himself as the Repertory Theatre’s artistic savior.

George Woods was educated enough to read the periodicals that carried the attacks by cultural kibitzers on Bob and me, but I doubt if he bothered. What he read were balance sheets, read them quickly—a glance at the bottom line would do—and he came to conclusions that led to action. During the period of my two disasters, George had accepted a job in Washington as head of the World Bank. But John Rockefeller, for all his soft-spoken ways, knew what he needed and went for it. He asked George to remain in a position of power with the Repertory Theatre and, particularly in this crisis, help out in the difficult days ahead. George agreed to continue as chairman of our board, and I believe his was a dominant influence behind the scenes in what followed. He chose a new president of the Repertory Theatre, a man who was the executive vice-president of the First National Bank. Robert Hoguet didn’t seem to me to be as bright as the other two men, but he was perhaps more pliable and readier to listen. If he had an opinion of his own about what he saw on stage and what would make more sense backstage, he didn’t allow his ideas to influence his behavior. He would consult George Woods; everyone consulted George Woods.

All three men were to react to the pressures brought on them from two directions—the box office failure of certain plays we’d produced, particularly my work, and what they’d read or were told about the attacks written by certain critics. Instead of putting the blame where it belonged, on me and my choices, these three men chose Bob Whitehead as the lamb to be sacrificed. The balance sheets spread on their desks spoke like Ouija boards and said, in the language they understood, that the root problem was the operating budget. From the beginning, Bob had warned George Woods that our deficit would be large. He’d made a startling and courageous statement, saying that a repertory theatre would always be a deficit operation, and that as we got better, our deficit would be larger, not smaller. This statement was intolerable to our bosses. It violated every principle on which their lives were built. They were also not prepared to pay for what they said they wanted. Instead they decided to get rid of Bob.

Now came the final episode in the life of our Repertory Theatre. The grotesque character of the events that followed cannot be appreciated unless the reader remembers that the men involved graduated from our best colleges, had read the best-sellers, dressed correctly, spoke convincingly on a variety of subjects and in the moderate tones of the well-bred, were perfectly at ease at a formal dinner, could tie a black tie and escort a lady to the opera, then gracefully to bed. These men were our elite. But in our final crisis they behaved like characters out of a cinema caper whose subject is a CIA-inspired plot and whose dramatis personae, bungling criminal conspirators, are all played by Peter Sellers.

IT IS Bill Schuman’s character to recognize a crisis and do something about it; according to Variety, he promised that he himself would provide the necessary artistic “input” in the future. What the Repertory Theatre needed now, he said, was a new administrator to replace Bob. He had a candidate to recommend, Herman Krawitz, an assistant manager of the Metropolitan Opera, the man who’d been in charge of setting up that operation in its new home at Lincoln Center and done it well.

Mr. Krawitz was under contract to the Metropolitan Opera and a favorite of the fiery autocrat who presided there, Rudolf Bing. Everyone knew how short and volatile Bing’s temper was, so knew they had to tread carefully as they approached Krawitz. Obviously, if anything of this kind was to be done, it had to be done with discretion and a delicate touch. Bill Schuman was the man for that, they all agreed. And Bill agreed.

Having received the approval of George Woods, which meant that Hoguet approved, Schuman decided he would feel Krawitz out secretly to ascertain his interest in replacing Bob—if the obstacles to the transfer could be removed.

What was being considered now reached John Rockefeller, a man superior in the ways of gentility. He urged Schuman to be sure to make his reach for Krawitz “through the front door,” which, translated, meant that any conversation Schuman wished to have with Krawitz should be discussed beforehand with Anthony A. Bliss, the president of the Metropolitan Opera, who was a gentleman, not a raging lion like Bing.

But Bliss was out of town at the time and Schuman thought it important to move without delay and feel Krawitz out before he spoke to Bliss; there was no reason to go through all this if, in the end, Krawitz was not interested. So he decided to find out discreetly, which is to say, secretly. All big shots, from time immemorial, have had lieutenants to whom they give assignments that they consider inappropriate for themselves. In this way they can disclaim responsibility if anything goes wrong. Instead of speaking to Krawitz himself, Schuman instructed Schuyler Chapin, a hell of a nice guy from academia, to sound out Krawitz and report back.

In the meantime, Anthony A. Bliss returned to the city, and Schuman met with him. Mr. Bliss opposed the suggestion. But Bill Schuman had not climbed to where he was in our world by being deterred so easily from reaching a goal. He still wanted to know if Krawitz would be interested if the way could be cleared of obstacles.

So Schuyler Chapin met with Krawitz, who was flattered, of course, but said no. He had a contract with Rudolf Bing and was concerned about Bing’s temper.

Schuman was still not deterred. He instructed Chapin to go back to Krawitz, hold another confidential talk, and offer a “sweetened” proposal. Krawitz would be both artistic and administrative head of the Repertory Theatre, replacing Bob and me, with an appropriate increment in salary.

This was indeed a tempting offer. Krawitz was tempted.

Bob Whitehead, who’d worked six years—four without pay—at Lincoln Center, whose sole interest during those years was the Repertory Theatre, and who was now to be replaced, was not informed of what Schuman was up to. Nor was I.

Rudolf Bing, for whom Krawitz worked and who held a contract with Krawitz, had not been informed or consulted by Schuman.

Now came the inevitable leaks. When I heard about what was happening behind our backs, I was certain, appreciating George Woods’s character, that he was calling the plays. I knew the intensity of the antagonism George felt toward Bob, and I believed that the force of this spite would overcome any tendency in George to caution, discretion, or kindness. The Repertory Theatre had to be saved, and the way to do it was to cut Bob Whitehead loose and replace him.

It was at this point that the fire-eating head of the opera heard what was going on behind his back and, bang, Bing blew up! “If our sister constituents are going to be free to raid each other, we’re back in the jungle,” he proclaimed, “and I don’t want to be in Lincoln Center.” With which, a man of his word, he resigned from the Lincoln Center top board.

John Rockefeller was distressed. I wondered what he said to Schuman.

Now all this could not be kept out of the newspapers.

Bill Schuman was publicly embarrassed, but I doubt George Woods gave a damn. He still wanted Bob out, one way or another. I suspect that he knew that what had happened would result in Bob’s walking away without another push, which was a hell of a lot easier—and cheaper—then firing him.

Bob and I were now hearing full details of what had been going on behind our backs and of our humiliation by the bankers. Bob was furious, I, disgusted.

Had we forgotten whom we were dealing with? It would have required more understanding and courage than these men possessed for them to have taken a stand at this point and replied to our critics, “Whitehead, Miller, and Kazan are good, devoted men. They haven’t had sufficient time to do the extremely difficult job we’ve asked for. That might need five years to accomplish. They are, however, already adjusting their policies so as not to make the same mistakes again. We believe they should go on.”

Nothing like that was considered. Woods, I imagine, had tasted the blood he wanted. In these situations, there’s always a victim.

Schuman was concerned about redressing himself in the public eye. He’d felt free to humiliate Bob, but didn’t favor humiliation for himself. So he sent another nice guy, Mike Burke, someone I might have considered a good friend except that he was the man George Woods had brought in to tip the balance of the board and defeat our proposal for the ANTA Washington Square Theatre, the proposal we’d made good on over George’s opposition.

Mike met with Bob “for a week.” I can’t imagine what they talked about for a week, because the proposal Mike conveyed from Schuman was simple—and insulting. How many different ways can a man pronounce “Quit”? They were asking Bob to continue for the rest of the season, knowing that he’d then be replaced.

Bob immediately “resigned to The New York Times.” In his statement, he asked how a man would work efficiently when he knew that, behind his back, he was being replaced, secretly at first, then openly. Had this question occurred to the board? It was never answered, nor did Bob need an answer.

Robert Hoguet, the new president of our board, did give his own statement to the Times. “We could not deter Mr. Whitehead,” he said, “from quitting.” And so on. All that when everyone who’d been following the chain of events knew that Schuman and Woods had been exerting every effort to make Bob quit. Hoguet also said that they’d “just been looking for someone to go along with Bob.” Which, it seemed to me, was simply a falsehood spoken falsely to save face. This astonishing statement was further soiled by an expression of regret.

When Bob resigned, Art and I resigned. It was then that George Woods took me aside and asked if I’d continue without Bob. I’ve heard that another member of the board asked Miller (who’d written the two plays that paid their way) the same question and got the same answer I’d given George.

So the effort to set up a repertory theatre in New York’s Lincoln Center, which had started with a burst of energy and hope, ended with falsehoods and the crunch of disgrace. After it was all over, Bill Schuman retreated into what he called a “dignified silence.” Which he nevertheless broke to make one astonishing public complaint. He said he’d been dismayed at the lack of brotherly feeling in the Repertory Theatre.

Whatever feelings of “dismay” Bill was feeling in his dignified silence did not deter him from bringing on our replacements. These men, the products of a highly publicized talent search, were Herbert Blau and Jules Irving, who had been urgently touted by the culture kibitzers who’d worked so hard and so long to displace Bob and me.

Blau and Irving, at the time of their first production, made the statement that they were going to offer “revolutionary” plays at Lincoln Center. Whom were they kidding? Themselves. They were to find out soon enough whom they were working for, and that any promises of independence they’d received could not be relied upon. For the playbill of their first production, Blau wrote copy linking President Johnson with certain international social despots. He was influenced—if that’s the word—to withdraw this slur tout de suite. If they really meant that their wish was to do plays espousing social revolution, Lincoln Center hardly seemed the platform from which to launch such a program.

I can’t help believing that their choice of plays had been made with a degree of consultation with our campus-based critics. Their choices were what could have been expected—another kind of standard fare. I doubt that Danton’s Death meant or could mean something very arousing to the audience who sat in the red plush seats of Lincoln Center’s Beaumont Theatre. On opening night, Jules Irving did something out of his naive good heart; he went from dressing room to dressing room before the performance, told actors that the future of the American theatre was in their hands. The actors they’d brought in from San Francisco may have believed this, but the actors they’d retained from our original company had another reaction: that the men who’d been directing them were fools and amateurs.

On the morning after the opening of Danton’s Death, Robert Brustein, our kibitzer with the sharpest teeth, wrote: “I cannot conceal my disappointment …” And so on. Clearly he would have wished to. He’d heralded the program of plays that Blau and Irving had announced. Now he didn’t try to conceal his disappointment at their production. Blau and Irving found they were building a theatre on a quicksand of opinion, and no one, not even their friends, was ready to give them even as much time as we’d been given to accomplish what they wanted.

A year later, I was told that Blau was on his way out and was offered his post. But I’d had more than enough of Lincoln Center and the men who ran it. I’d decided to follow my own bent and write novels. Then I wouldn’t be at the mercy of a board of real estate operators and bankers.

There was one surprise in all this history. Whereas there had always been some reservation within me about working at the Repertory Theatre—especially after I’d written and produced my own film—or in any theatre of any kind, a doubt that this was really what I wanted to do and what I was good at, I found that when I was edged out with Bob and became the butt of critical target practice, I was mad as hell. During the years I’d devoted to the Repertory Theatre, I’d often felt that I was not doing what I truly wanted to do. But when it was all over, I was furious. I didn’t like failing, not at anything I undertook; I didn’t like leaving as a loser and I didn’t like the way we’d been manipulated out. I didn’t like the way Bob had been treated and I resented that Art had been insufficiently appreciated. I knew how good these men were, how hard they’d worked, and that Lincoln Center would never find their like again.

When it was done, friends could see on my face what I was feeling, and some thought I was cracking up. Deciding to remain apart from everyone, I’d disappeared from view. Whereupon several actors, old friends, worried about my health, sought me out to see what was eating me and could they help. I told them no, thanks, I felt fine, which worried them more. Didn’t I even know that I needed help?

What was “eating” me made me turn my back on the theatre and never go back to it. I’d made up my mind that I’d not direct anyone else’s work again, that now I’d write my own screenplays, as I had with America America, and possibly try myself on a novel.

Before I put these memories behind me, I must say something about the Actors Studio Theatre and what happened there.