6Border Thinking/Being/Perception

Toward a “Deep Coalition” across the Atlantic

Madina Tlostanova

Lugones’s work offers paradigmatic examples of border being, thinking, and perception within the decolonial thought—an international collective of scholars who, for the last two decades, have been conceptualizing the underside of modernity—that of coloniality. Together, we understand coloniality as a consistent cultivation and maintenance of the economic, social, cultural, ethical, epistemic, and ontological dependency on Western norms and assumptions presented as universal and good for all. The decolonial option is also about possible ways out of coloniality in spheres of power, being, knowledge, perception, and certainly gender, all of which triggered the formulation of Lugones’s concept of the colonial/modern gender system (HGS). I believe that the combination of the border way of being in the world and communicating with others, offered by Lugones under the name of world-traveling with a loving perception, and her model of the coloniality of gender and a coalitional opposition to it from the colonial difference are relevant not only for the sphere of coloniality of the Western empires of modernity and their gendered others, but also for the colonial difference of Russia (WT, CG). Previously, I have theorized Russia as a second-class, subaltern empire, whose former and present, particularly non-European, colonies (mainly the Caucasus and Central Asia), have been marked by a complex intersection of gender, race/ethnicity, class, religion, language, and geopolitical positioning (Tlostanova 2010a). This Eurasian configuration complicates Lugones’s original ideas and must be considered in dialogue with them yet also as a separate model.

Such a dialogue is possible because Lugones’s work on gender does not investigate concrete cases of discrimination or offer a descriptive historical analysis of gender in othered cultures; instead, it operates on the level of epistemic de-linking. This means undermining the very epistemic and logical principles of modernity/coloniality with its universally accepted scholarly myths and grand narratives of progress, development, democracy, human rights, gender difference, and equality. Such a “learning to unlearn in order to relearn” (Tlostanova and Mignolo 2012, 7) often leaves us with meager conceptual instruments and a necessity of elaborating new concepts or digging out the marginalized and forgotten ones by tracing alternative genealogies and trajectories of local histories where, in Lewis Gordon’s formulation, the modern ratio-dicea becomes inapt (2010).

In what follows I will try to demonstrate—through a decolonial stance—the potentially fruitful spheres for a dialogue between Lugones’s ideas and resistant gender discourses of and in the Caucasus and Central Asia. The Caucasus and Central Asia constitute the two main spheres of coloniality within the former Russian/Soviet empire. They share a number of common elements found in other decolonial border positions of exteriority—a philosophic synonym of border thinking and existence, the outside created from the inside—from the totality of the dominant discourse (Dussel 1985). Such an exteriority, grounded in the experience of being born and educated in the entanglement of the Western invention of modernity/tradition, is not calling for a return to some primordialist state, but, rather, draws our attention to how and why modernity invented the negative image of tradition in the first place. The exteriority of living and thinking in hostile environments while reinstating one’s epistemic rights leads to an itinerant, forever open, and multiple discourse marked by transformations, shifting identifications, and a rejection of either-or binarity. In this trajectory, one turns, instead, to a nonexclusive duality and un-sublated contradictions, which are to be found both in the contemporary models of conjunctive logic and in many Indigenous epistemologies, including the better investigated global South as well as the lesser-known Caucasus and Central Asian models.

The first intersectional node between Lugones’s thinking and Central Asian and Caucasian resistant discourses of gender is questioning the binary of modernity versus tradition that permeates all cultural, social, political, and religious relations, academic disciplines, and knowledge production. In the sphere of gender, this is expressed in questioning the assumed patriarchal nature of any traditional society and in revealing the (hetero)sexist limits of colonization/modernization grounded in the dichotomy of the same and the other, subject and object, man and woman. Decolonization of gender, then, presupposes questioning the invention of secular modernity and its dark other—tradition—associated with backwardness, patriarchy, humiliation, violence, filth, ignorance, and so on. Other falsely universal ideas of Western feminism questioned in decolonial feminist thought include egalitarianism, fragmentation of identity, linguistic sexism, naturalizing of sexual differences, and the visual (masculine) nature of any culture (Tlostanova 2010a).

The coloniality of gender takes different guises yet always retains its main features of the heteronormative and patriarchal division of humanity and the main vectors of discrimination, resistance, and empowerment of those who have been systematically dehumanized. From such experience emerges a new trans-aesthesis connecting people throughout the world who have suffered Anzaldúa’s open (colonial) wound between the lighter and the darker sides of modernity (1999, 25), but who have also learned to build a positive “resisting and re-existing sensibility” and agency out of this trauma (Albán Achinte 2009). Lugones’s decolonizing of gender as a false imperial concept is a crucial step on this path. She shows that the concept of gender legitimates modern pseudo-scientific human taxonomies such as the division of people into humans and subhumans (sexually and racially marked) or, in Nelson Maldonado-Torres’s idea, the enactment of “misanthropic skepticism” questioning the humanity of the other, and is grounded not in ontological but in epistemic and artificially constructed differences (2007). Lugones’s attempt to get rid of the biologicalization of gender is thus linked with a wider decolonial impulse of uncovering the role of particular situated knowledges in any ontology.

It is crucial to examine what mechanism lies in the basis of the discursive decolonization of gender. And there are several intersections between Lugones’s method and those nascent positions that we find in the zone of the colonial difference of the Russian/Soviet empire. Of particular significance is her nuanced and truly dynamic intersectional approach, generating multiple shifting positionalities and an optics of complex stereoscopic and pluritopic (that is, multispatial) vision, opposed to structuralist, Marxist, and standpoint intersectional approaches. Such a stance is grounded in the body-politics and the geo-politics of knowledge, being, gender, and perception, marked by the colonial difference instead of the Western, deliberately delocalized vantage point.

Geo- and body-politics represent epistemic and political projects from historical agents, experiences, and memories that were erased in the capacity of epistemic subjects. Lugones calls these politics “the peopled ground” on which one stands and which also run through one (TDF 746). The geo-politics of knowledge, being, and perception refers to the local historical (temporal) and spatial grounds of knowledge and existence. The body-politics can be defined as the individual and collective biographical grounds of understanding, thinking, being, and perception rooted in our local histories and trajectories of origination and dispersion. Such an intersectionality, grounded in a coalitional logic of fusion, intermeshing, and coalescence is pluriversal in the decolonial sense (RM 73), meaning a coexistence of many interacting and intersecting nonabstract universals based on the geo-politics and body-politics of knowledge, being, and perception (Tlostanova and Mignolo 2012, 65). The pluriversal involves a conscious effort to reconnect theory and theorists with experience and with those who experience discrimination; in other words, it seeks to reinstate the experiential nature of knowledge and the origin of any theory in the human life-world. In the pluriversal world, many worlds coexist and interact, and countless options communicate with each other instead of promoting one abstract universal good for all. These options intersect, sometimes inside our bodies and selves, and each locus of intersection is another option. Decolonial pluriversality is parallel to intersectionality, but its target is not the constellation of race, gender, class, and other power asymmetries, but rather the aberration of the universal as such, the stress on the epistemic (not ontological) nature of othering. This allows for looking at different locales, including the Caucasus and Central Asia, through a dialectic of transition from intersectionality to fusion as a much better ground for a potentiated coalitional resistance (RM 76).

If Lugones’s trajectory grows out of her geo- and body-politics of knowledge, being, gender, and perception, grounded in the colonial difference with the Western capitalist empires of modernity and a diasporic existence in the United States, the local history of peripheral Eurasia demonstrates a much more blurred and complicated case due to the external imperial difference and its darker counterpart—a secondary colonial difference. The imperial difference refers to various losers, which failed to fulfill, or were prevented by different circumstances and powers from fulfilling, their imperial mission in modernity. They were intellectually, epistemologically, or culturally colonized by the winners. Imperial difference can be divided into internal and external kinds. The former refers to the European losers of the secular phase of modernity, which became the South of Europe (Spain, Italy, Portugal), while the latter refers to the non-Western, noncapitalist, non-Catholic/Protestant, alphabetically non-Latin empires of modernity, for instance the Ottoman Sultanate or Russia. The latter is a paradigmatic case of a second-class non-European empire with a long and unsuccessful history of borrowing and superfluous appropriation of certain elements of modernity, and a chronic mental coloniality vis-à-vis the West.

The first phase of the Russian imperial expansionism was largely directed to Siberia, and its logic generally corresponded to the Western logic of the first Christian colonial modernity within which the central dichotomy was the hierarchy between the human and the nonhuman (TDF 743). From this major division, other binaries emerged such as men versus women, and white versus nonwhite. From the sixteenth century on, Russia has gradually internalized the European interpretation of non-European people as under-humans and has worked to forge the European roots of noble ethnic Russians (as opposed to peasantry), accentuating the often-problematic Asiatic lineage of its colonial non-European others. In doing so, Russia constructs the colonial difference (which, in the Russian case, has always been vague, due, in part, to the lack of an ocean between the poorly defined metropolis and the colonies). The conquest of Siberia in the late sixteenth century corresponds to the European model of identifying the Indigenous people (in this case, the numerous tribes of Itelmen, Yukagir, Nivkh, Tuvans, Siberian Tatars, Selkups, and others, in many ways similar to Amerindians) with nature. This familiar logic liberated the Russian colonizers from any responsibility for the equally marauding attitude to both nature (as peltry, not oil, was the main commodity Siberia provided then for the international markets) and the Indigenous people. The social-military groups of the so-called Cossacks conquering Siberia often married the Indigenous women. This resulted in a significant number of Russian “Creoles,” later completely assimilated and today considering themselves ethnically Russian. However, in the mid–nineteenth century, progeny of this Siberian Russian-Indigenous mixing already made a number of decolonially charged statements denouncing the bloody imperial acts while using this local history to build a political platform for the struggle of regional independence from Moscow. This sentiment is actively revived today. Thus, half-Russian and half-Buryat historian Afanassy Schapov criticized the Russian zoological economy that is the parallel annihilation of fur-providing animals and Indigenous people who were forced to hunt them under pain of death (1906). At this early point, all women (both Russian and Indigenous, legal wives and concubines) were regarded by the Siberian conquerors as commodity and property, subject to slave trade and lease (it was common to rent one of one’s several wives—no matter Russian or Indigenous—while embarking on the next colonization campaign) (Scheglov 1993). There was yet no gender involved here, only biological sex, and gender was not used as a social and cultural marker of belonging to humanity. As a social concept gender appeared much later and was largely determined by class rather than race/ethnicity (Etkind 2011; Tlostanova 2010a).

If the conquering of Siberia more or less corresponded to the Spanish and Portuguese expansion in the New World, the Caucasus (southward) and Central Asia (eastward) annexation took place in post-enlightenment modernity, when racial and gender divisions were already codified and ossified through the rhetoric of secular Western modernity that the Russians, once again, internalized as their own. Moreover, Russia’s own subaltern status in the world-imperial ranking and its catching-up modernizing pace was also firmly naturalized starting from Peter the Great, and confirmed the paradoxical situation of the empire-colony that has generated its own secondary colonial difference. The colonial difference is secondary because of the subaltern and mimicking nature of the empire in question—a Janus-faced empire with different faces turned eastward and westward. It has always felt itself inferior to the West—an out-of-place Tatar dressed as a Frenchman (Kluchevsky 2009). Russia has compensated for this inferiority complex in its non-European colonies (and mainly in the Caucasus and Central Asia) by projecting the image of the Russian/Soviet colonizer as a true European and a champion of civilization, modernity, socialism, and so on. As a result, these colonies were doubly subordinated to Western modernity and to its distorted Russian version, which has still retained, in mutant forms, the main features of modernity, such as Eurocentrism, progressivism, Orientalism, and racism. The Caucasus and Central Asia thus became the colonies of the culturally and mentally colonized empire.

The local histories of the non-European ex-colonies of the Russian empire and the USSR generate multilayered identifications, ways of survival and re-existence and intersectional tangents growing out of the multiple dependencies from modernity/coloniality in its Western, and also insecure Russian and Soviet, forms, as well as from complex and often contradictory religious and ethnocultural configurations. They disturb the simple binarity of the colonial/modern gender matrix as they multiply, destabilize, and problematize many familiar categories of decolonial thought. This refers to a redoubling of Orientalism and Eurocentrism, to an increasingly symbolic nature of racism, to a complication of imperial and colonial masculinity and femininity, as well as colonial gender tricksterism.

Secondary Orientalism in the Russian/Soviet empire is a direct result of secondary Eurocentrism—a nonoriginal derivative discourse, borrowed from Western modernity and appropriated and distorted by the Russian imperial consciousness, to be later imposed onto the colonial others. Moreover, this appropriation of the Western modernity’s discourses is done by the Russians who, themselves, have always been seen by the West as Asiatic, Oriental, and savage and, therefore, have developed an inferiority complex compensated at times by exaggerated jingoism, as it happens today. Therefore, Russian Orientalism, Eurocentrism, and racism are grounded in a peculiar transfer: they attempt a redemption, getting rid of the non-White man’s burden through an artificial and exaggerated appropriation of Whiteness and belonging to Europe, but always with a hovering realization of the dubious Russian status under Western eyes. Orientalist constructs, in the case of Russian empire and its non-European colonies, are built on the principle of double mirror reflections, on copying Western Orientalism with a deviation and, necessarily, with a carefully hidden, often unconscious, feeling that Russia itself is a form of a mystic and mythic Orient for the West (Sahni 1997; Tlostanova 2010a). As a result, both mirrors—the one turned in the direction of the colonies and the one turned by Europe in the direction of Russia itself—appear to be distorting mirrors that create a specific unstable sensibility, expressed in Victor Yerofeyev’s ironic dictum: “If I want, I can go from Moscow to Asia, or—to Europe. It is clear where I am going to. But it is unclear where I am coming from” (2000, 56). It is a balancing between the role of the object and that of the subject in the epistemic and existential sense.

Race as a universal classification in modernity/coloniality has been masked in the Russian and Soviet history by ethnicity and/or religion and later by class or ideology, leading to a highly symbolic nature of racism disconnected from the purity of blood or the color of skin. This made it difficult for outsiders to understand the rules of Russian imperial racist taxonomies and its colonial self-racializing (Central Asia) or self-Whitening (the Caucasus) versions. Once again, as in the case of Siberia, which consists of many tribes and emergent nations belonging to quite different linguistic groups, religions, and cultures, the conquered people of the Caucasus were coded subhuman and therefore had to be seen as non-White savages, even if in the European and North American imaginary of the time the Caucasian race—that is, originating in the Caucasus, according to an early (pseudo)anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, was (and still is) a synonym of Whiteness. The purity of blood could not save the Caucasus women from being raped, killed, or sold into slavery (usually to the Ottoman Sultanate).

In the Czarist empire, religion was translated into racial/ethnic categories. For example, Muslims became Tatars (nineteenth century), then bourgeois nationalists (USSR), and today—simply “Blacks.” In the Soviet Union class and ideological characteristics were often translated into racial and ethnic ones. Racializing had one face in the metropolis (when the “enemies of the people” of any ethnic and religious belonging were rendered subhuman), and a different face in the colonies where the discourses of the civilizing mission, development, progressivism, and Soviet Orientalism clearly demonstrated their links with the Western colonialist macronarrative. The lighter side of Soviet modernity was grounded in ideological and social differences, whereas its darker side reiterated the nineteenth-century racist clichés and human taxonomies mixed with hastily adapted historical materialist dogmas. Soviet efforts to create its own image of the New Woman in her metropolitan and colonial versions grounded in the typically Soviet double standards and reticence place contemporary gendered subjects from the ex-colonies of Russia/USSR into a complex and undertheorized intersectional zone between postcolonial and postsocialist realms (Navailh 1996; Tekuyeva 2006; Tokhtakhodzhayeva 1999). In the post-Soviet decades, the ruins of the USSR have become, for the rest of the world, a homogenized problematic region in a post-Duboisean collective sense of the people with delayed or questioned humanity and no place in the new global architecture. In the cases of the ethnic Russians themselves and the ex-colonies with European claims (such as Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltic states, Moldova), it is not a clearly racialized division, but, instead, a poorly representable semi-alterity, the realm of the off-White Blacks of global coloniality, looking and behaving too similar to the same, yet remaining essentially others. A border case is the Caucasus, which is actively demonized and blackened by Russia and excessively preoccupied with its self-Europeanization as a compensatory gesture. As for Central Asia, whose ethnic, linguistic, and religious belonging to the Orient cannot be disputed, it managed to take an honorary place in the second world due to Soviet modernity. Today, Central Asia is not ready to agree with its clear belonging to the global South or to work for the development of coalitions and praxis in that direction. By this I mean the local intellectuals infected by secondary Eurocentrism and not the mute subalterns for whom their physical survival is the only goal. All of these are signs of the continuing coloniality of thinking and coloniality of knowledge, which, in the Central Asian case, redoubles in the fawning both before the Russians and the West.

The Russians appropriated the modern gendered and racialized human taxonomies and shaped their own, more complicated, version of the paradox of colonial femininity and masculinity in which the main element of taking humanity away from the colonized has stayed intact. Russian imperial double-consciousness, briefly outlined above, leads to a distortion of most modernity discourses, including those about gender. The colonial gender paradox is based on blaming the colonial others for mutually exclusive vices at once, and is closely linked with the major modern division of humanity into humanitas and anthropos, the latter being locked in the realm of nature, not culture (Nishitani 2006). Gender is obviously a construct of the humanitas invented in order to differentiate its constituents from those that belong to nature and therefore have only biological sex. The definition of colonial femininity and masculinity is self-denying and preventing the colonial subject from building a positive identity. Racialization works, then, through gender, and colonization itself comes to be symbolized as an act of rape or violence. However, this well-known story is typical of the confident empires with a positive masculine identity, whereas Russia has always been an unconfident second-class empire, itself codified as feminine by the West. Its attitude toward colonized people has been marked by a suppressed diffidence and an exaggerated self-assertion linked with a realization of its insufficient (for the empire) superiority over the colonized, particularly in gendered/sexual spheres. Due to the coloniality of gender enmeshed in contradictory impulses, the colonial man in the colonies of the Western empires can be easily feminized (particularly in Orientalist versions) as he lacks any real authority or power. And yet, any hint of his possible will or agency is immediately interpreted as a threat to White society, which presents the colonized male as an essential rapist and an aggressive animal, threatening the chaste White lady (especially in African and some Amerindian stereotypes) and his own women, seen by the Western society as being in need of rescuing from their own males. The non-White woman is regarded as sexually available, voracious, and willing to be raped, a seductress of the White man and a threat to the happiness and well-being of the decent White lady, lacking chastity or honor as such and thus liberating the White rapist from any guilt or responsibility.

In the Russian colonization of the Caucasus and Central Asia, this naturalized ethics was recast in particular ways, connected not with race but with essentialized ethnicity and, later, with Islam, which was early translated into racial terms when the Muslim of any origin equaled “non-White” and hence “subhuman” (Tlostanova 2010b). The paradox of colonial masculinity and femininity differed from the West because the gap between the Orientalist European fantasy and the reality of the Caucasus and Turkistan (the Czarist name of Central Asia) conquest was too obvious and based on the secondary Orientalist ideologies, always poisoning any victory for the subaltern empire.

Muslim and local ethnocultural custom protected the Central Asian Muslim women from the Russian colonizers. They could not act in the role of non-White women in the European colonial imaginary. The Caucasus women, for a while, played the part of exotic sexual slaves and were a profitable commodity, habitually compared by the Russians to animals and associated with familiar characteristics of early puberty, heightened sexuality, and wanton morals (Tlostanova 2010a, 73). However, there were no Black slaves or Amerindians in the Russian colonial spaces (save for the earlier conquests of Siberia and the Far East, which resulted in the extermination or assimilation of the local equivalents of Amerindians). Besides, as stated above, the boundary between the metropolis and the colonies has been always blurred in the Russian case, so European racial classifications had to be transformed and eventually divided between the two human groups. On the one hand, there are the ethnically same (that is, Russian) but socially and culturally inferior serfs (peasants bound by the feudal system to work on their master’s estate) who were ruthlessly exploited and dehumanized by the Russian nobility and the state, and who resided mainly in central Russia (and not in the colonies). On the other, there are the inhabitants of the newly colonized spaces of the Caucasus and especially Central Asia who were hardly ever subdued into serfdom yet were still dehumanized, robbed of their lands and other property, and generally deprived of most civil and human rights on the basis of racial/religious taxonomies.

The local men in the Caucasus could not be interpreted within the Orientalist docile stereotype, and any comparison with them was not to the advantage of the much more tepid Russian masculinity, which used the Caucasus male archetype as an attractive sexual model—noble savages who had fallen out of modernity and progress. The erotic element of Russian imperialism—contrary to its European versions—was expressed in the male form and extrapolated into the Russian male anxiety and fear of the Caucasus machismo in war and sex (Sahni 1997, 33–69; Tekuyeva 2006). Therefore, in Russian gender stereotyping of the Caucasus, the local colonial men were associated with violence but never feminized. In Soviet modernity, the light (modern) and the dark (colonial) sides merged in the interpretation of the colonial periphery so that the Caucasian people were racialized and presented as unreformable. Yet, it was paradoxically assumed that, under the influence of Russian/Soviet civilizing efforts, the mountaineers would gradually turn into a different sort of people (Jersild 2002, 9–125). The post-Soviet society retains the gender stereotype of the dangerous Caucasus man, which is used today as the basis of standard racist accusations—from his desire to possess a Russian woman and humiliate Russian men, to his dangerous tendencies of reckless courage. The latter impulse is often seen as a readiness to sacrifice lives—his own and other people’s, including women—the so-called black widows, the suicide bombers of the Caucasus Islamic separatist movements.

Several decades after the colonization of the Caucasus, the Russian conquering of Central Asia was already a pale and distorted copy of the British and French march to the Orient, coding the local population as subhuman and, once again, almost animal—this time within the frame of the newly emerged pseudo-scientific anthropology. As late as the 1920s, Soviet “experts” interpreted the Central Asian women with the help of almost zoological visual comparative charts, completely ignoring their humanity. But colonized Central Asian females were substantially different from the African slaves or Amerindians. Central Asian women were not turned into an important part of the economy of sexual and labor exploitation until the Soviet colonial cotton industry emerged in Central Asia, with its racist and misogynist division of labor. Because there was no system of direct colonial slavery in Czarist times in the Caucasus or in Central Asia, it was impossible to create a unified, systematic, and coherent system of labor and sexual exploitation for colonized women. The ethnically Russian serf woman, who resided in the Russian version of the metropolis, performed the role of the sexually, economically, and psychologically exploited female, often seen as an animal and taken out of the realm of the human and feminine (Etkind 2011, 124–28).

In post-Soviet decades, global coloniality started to affect the post-Soviet space directly and not through a mediation of Russian or Soviet imperial difference any more. This has sadly led to a revival of gendered—and this time clearly racialized—slavery. The Central Asians are still seen in modern-day Russia as dirt poor and placed at the bottom of the scale of humanity, to the point of erasing gender markers altogether and seeing so-called illegal women migrants as animals: these women are regarded as biologically female yet culturally and socially subhuman. They are Agambenian bare lives (ab)used in forced overwork and sexual trafficking, and as producers of children sold in the capacity of live goods (1998). There is no future for such ex-slaves. They cannot go back home where the slave trade mafia is going to punish them, or they will simply perish of hunger and unemployment. These people were born and made to exist in the grip of global coloniality, both in the neocolonial world of Central Asia and the postimperial (and also neocolonial) world of the ex-metropolitan Moscow.

The trajectory of these Central Asian migrant bare lives is different from African American women or Latinas in the United States, as it was complicated by dubious Soviet gender discourses and practices. The ancestors of the future post-Soviet downtrodden migrants from Central Asia experienced double standards, racism, othering, forceful emancipation, and low glass ceilings along with all other non-Russians in the USSR, but they also had access to such socialist advantages as universal education (even if Russified and not always of good quality), minimal social guarantees within the colonial monoeconomic model, restricted social lifts for national minorities in accordance with Soviet multiculturalism, and an honorary belonging to the second world that the Central Asians have lost today. It is crucial to keep this in mind when tracing the trajectory of Central Asian women toward their contemporary condition of neoslavery and Central Asia’s firm belonging to the global South without the benefit of sharing its political agency and epistemology.

There are several reasons for this failed solidarity between post-Soviet/postcolonial and global South women. These reasons include the lack of information or access to any relevant texts and the lack of mutual communication in the conditions of persistent isolation of such locales as Central Asia and the Caucasus. This is compounded by a continuing sharp division into the thin layer of intellectuals who could potentially act in the capacity of decolonial agents yet choose not to because of their coloniality of knowledge, and those who obediently follow the old logic. It consists in Russian/Soviet and, today, more often, Western thinkers producing high theory, which then is quoted, repeated, and simply applied to concrete examples from their own experience by the local Central Asian or Caucasian intellectuals. Part of the problem lies in the fact that a newfound gender sensitivity has come to post-Soviet postcolonial spaces from the West, assisted by various grants and institutions that often require a very particular interpretation of gender issues and tend to erase the previous history of gender struggles and models, thereby forcing postcolonial, post-Soviet women to start from scratch in the mode of mainstream Western feminism.

This mode alienates mainstream theorists from the majority of Central Asian and Caucasian women living and struggling in their locales. For these women, Judith Butler’s work, likely known by heart among the local scholars indoctrinated by Western feminism, does not mean much. Central Asian and Caucasian women would probably find much more in common with Lugones’s project, which remains untranslated and unknown due to the specific preferences of local gender scholars who have been marked by intellectual coloniality. Another reason for the absence of Central Asian and Caucasian voices in gender discourses of the global South today is linked to a persistent agonistic model and an unwillingness to cede one’s status as “second world” and be associated with the global South. Third, there is a phenomenon of negative victimhood rivalry expressed among some ex-third world cases where people tend to monopolize their position as victims of modernity, refusing to make room for obscure Caucasians or Central Asians. Overcoming these difficulties requires goodwill from all sides, which is, at times, problematic.

Parallels and divergences between Lugones’s decolonial feminist categories and that of the external imperial difference and its secondary colonial difference bring us to the issue of praxis, or a lack of it, in the post-Soviet case. In a number of her recent texts, Lugones elaborates on such relational oppositional praxis and the emergence of flexible, nonossified, deep coalitions of resistance, crucial for any decolonial gendered efforts aimed at the creation of the transmodern as an other-than-modern world. Such an oppositional praxis is grounded in a nomadic traveling mode of existence, which sees culture itself as a journey and a process of social construction. This brings us back to Lugones’s idea of making a journey between worlds of meaning with a loving perception. This is the gist of decolonial border epistemology and ethics grounded in the idea of being the border, having the border cutting across one’s own self, not merely crossing borders and observing them from a detached pseudo-objective vantage point (Mignolo and Tlostanova 2006). Growing out of the situation of ontological othering, and resulting in re-existence, this position allows building a specific intersubjective model beyond the well-known ways of dealing with difference and diversity that could potentially lead to future deep coalitions of interrelated others.

Rejecting the Western concept of agon and playing, based on aggressive competitiveness as the main principle of social, cultural, political, and economic relations of winners and losers in modernity, Lugones formulates the nonaggressive “loving perception” of a playful world-traveler uninterested in who wins and who loses and who is, instead, forever ready to change. It is a decolonial counterbalance for the official failed forms of boutique multiculturalism and for the impasse of both absolute and opaque otherness and the convenient erasure of differences (WT 96). This recipe is crucial for post-Soviet space because it allows us to de-link from the coloniality of being and knowledge that prescribes the slaves of modernity to aspire for a solidification of a particular space for themselves in its hierarchy, being afraid of losing it, and, thus, ruthlessly competing with other others for the proximity to the same. All of this has been expressed in the complex of catching-up modernization and its accompanying psychological failures of external imperial difference and double colonial difference in the Russian empire and in the USSR, as well as in today’s collapsing Russian Federation.

In the (post)colonial side of post-Soviet space, the rejection of agonistics finds its parallels, marked by a specific ethics of intersubjective encounters, resonating with Lugones’s loving world-traveler’s stance. It is grounded in the idea of all-encompassing interconnection of people, nature, cosmos, where each of us represents the other. As an Uzbek Sufi healer tabiba Habiba states, quoting her teacher Bahauddin Nakshbandi, “take a hand—we can concentrate on the differences between each of the fingers, marveling how dissimilar they are, but then we risk not noticing the movement of the hand as a whole” (Allione 1997). In Lugones’s terms, we then risk cutting off the possibility of deep coalitions-in-the-making.

These ideas intersect with Lugones’s concept of communal infrapolitical and body-political resistant praxis (TDF 755). I see it ideally as grounded in the grassroots embodied and historically contextualized level of mutually communicating women’s movements within the global colonial difference. This is a good recipe for the Eurasian colonial difference that needs to get rid of its multiple complexes connected with a doubly colonized status, stop looking in the direction of imperial sameness or imperial difference, and start looking in the direction of global colonial difference with different, but intersecting, faces and local histories woven together by global coloniality and pluriversal resistance to it.

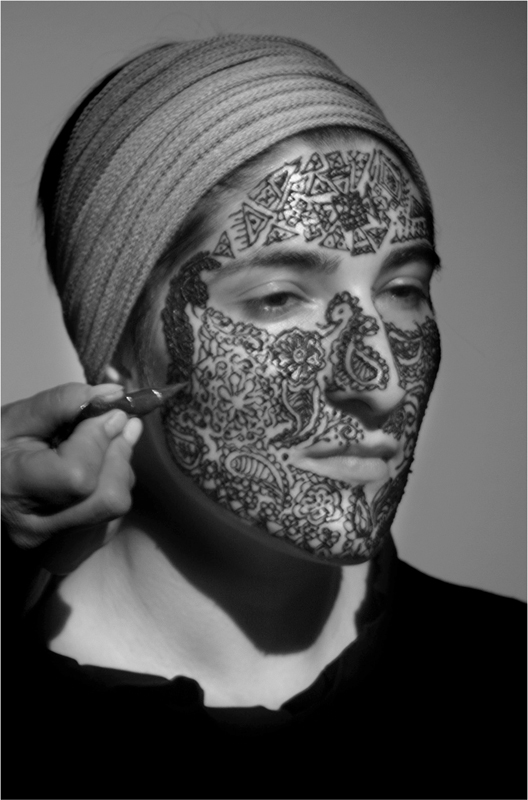

A young Avarian (Northern Caucasus) diasporic artist, Taus Makhacheva, offers an interesting example of such a position as an intersection of being and knowledge. A playful trying on of various alien roles does not rule out her remaining a part of the symbolic Indigenous reality in dialogue with modernity, which she investigates. Through the prism of a specific negotiating stance, the artist examines the unstable boundary between acceptance and rejection, drawing attention to human efforts to merge, mimic, assimilate, or leak into the other, no matter if it is another person or a community—natural or social, rural or urban, real or imagined. In Delinking (fig. 1), Makhacheva is attracted by the idea of de-linking from European ways of receiving knowledge and stresses that all cultures have their own practices of transmitting knowledge, while the world uses only the sanctified Western system. Makhacheva’s face was intricately painted with henna using Indian, African, and Middle Eastern ornaments.

Figure 6.1. Delinking by Taus Makhacheva, 2011. Photograph, 45 cm x 30 cm. © Taus Makhacheva.

Soon the whole face was covered with superimposed inscriptions. After the dry green mass was washed off, the visage changed its color to orange-brownish and stayed so for a week—a new mask, a new mocking identity—tentative yet leaving an obvious trace. The artist manages to graphically represent the decolonial principle of irreducible multiplicity that Lugones discusses in many of her works, the many logics never synthesized or hybridized, and never transcended. The changing face color, as a place for multispatial overlay of different epistemic and aesthetic systems, becomes a complex metaphor for a decolonial shift in the geography of reasoning and a recreation of a fluid decolonial community of sense, to paraphrase Jacques Rancière’s dictum, merging the ideational and the visceral meanings of the word sense (2009).

Lugones formulates the goal of decolonial feminism as “constructing a new subject of a new feminist geopolitics of knowing and loving” (TDF 756). But if and how can we—the inhabitants of Eurasian borderlands—join this global gendered decolonial community of sense? In the Caucasus and Central Asia, Soviet modernity is replaced with either the Western progressive model or the national(ist) discourses characteristic of young postcolonial nations, allowing for only specific propagandistic models of national culture, creativity, and religiosity. Even the works of many local scholars, who are forced to buy their way into the academic sphere by conforming to mainstream Western gender research, erase or negatively code the complex Indigenous cosmologies, epistemologies, ethics, and gender models discordant with modernity/coloniality. It is therefore important for ex-colonial postsocialist gendered others to get acquainted with non-Western approaches to gender. These approaches are coming from theorists/activists of the global South who are seeking deep coalitions grounded in the intersections of our experience and sensibilities. Moreover, these theorists/activists of the global South are hoping to (re)create a flexible gender discourse, one that would answer the local logic and specific conditions while also correlating with other decolonial voices in the world.

To do this it is necessary to take a border position, negotiating between modernity and its internal and external others, between the frozen categorial thinking and the fusion of intermeshing realities. This would allow de-essentialized, flexible, and dynamic groups to understand each other in their/our mutual struggles. At work here is a horizontalized transversal networking of different local histories and sensibilities mobilized through a number of common, yet pluriversal and open, categories, such as coloniality or the postsocialist imaginary. Such networking would enable us to replace the categorial and negative intersectionality that entraps women in situations of sealed otherness and victimhood and merely diagnoses their multiple oppressions, with a more positive re-existent stance of building an alternative world with no others.

This would lead to a shift toward a more conscious praxis, building a ground for a future solidarity. Transversal crossings of activism, theorizing, and contemporary art are some of the most effective tools in social and political struggles against multiple oppressions and in the creation of an other world where many different worlds would coexist co-relationally and communicate with each other in positive and life-asserting ways, aimed at restoring the right to be different but equal. It is necessary to work further on a critical language that would take into account existing parallels between various echoing concepts and epistemic grounds of different (post)gender oppositional discourses. Then post-Soviet non-European gendered others can hope to find their/our own voices in the global chorus against the many faces of coloniality.

Lugones’s architectonically complex and nonlinear mode of argumentation balances on the verge of theory, verbal art, and prophecy while reflecting local histories and subjectivities marked by coloniality and grounded in centuries-old oblivion, appropriation, and distortion and an existence always in defiance to modernity. As such, her decolonial feminist work can act as a beacon for the Eurasian borderlands, facilitating its belated joining in the decolonization of gender as a strategy that liberates being, knowledge, and perception from the constraints of modernity/coloniality. This joining in the decoloniality of gender will enable the Eurasian borderlands to become part of those emerging alter-global coalitions of solidarity in difference and multiplicity which, rooted in oppositional consciousness, may foster pluriversality and creativity as essential elements of our existence.

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Albán Achinte, Adolfo. 2009. “Artistas Indígenas y Afrocolombianos: Entre las Memorias y las Cosmovisiones: Estéticas de la Re-Existencia.” In Arte y Estética en la Encrucijada Descolonial, edited by Walter Mignolo, 83–112. Buenos Aires: Del Siglo.

Allione, Constanzo, dir. 1997. Habiba: A Sufi Saint from Uzbekistan. Film. New York: Mystic Fire Video.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1999. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Dussel, Enrique. 1985. Philosophy of Liberation. Translated by Aquilina Martinez and Christine Morkovsky. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock.

Etkind, Alexander. 2011. Internal Colonization: Russia’s Imperial Experience. Cambridge: Polity.

Gordon, Lewis. 2010. “Philosophy, Science, and the Geography of Africana Reason.” Lichnost. Kultura. Obschestvo (Personality, Culture, Society) 12(3): 46–56.

Jersild, Austin. 2002. Orientalism and Empire. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Kluchevsky, Vassily. 2009. Kurs Russkoy Istorii (A Course in Russian History). Moscow: Alfa-Kniga.

sharjahart.org/sharjah-art-foundation/people/makhacheva-taus

Maldonado-Torres, Nelson. 2007. “On the Coloniality of Being.” Cultural Studies 21(2–3): 240–69.

Mignolo, Walter D., and Madina Tlostanova. 2006. “Theorizing from the Borders: Shifting to Geo- and Body-Politics of Knowledge.” European Journal of Social Theory 9(2): 205–21.

Navailh, Franşoise. 1996. “The Soviet Model.” In A History of Women in the West: Towards a Cultural Identity in the Twentieth Century, edited by Franşoise Thebaud, 226–54. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Nishitani, Osamu. 2006. “Anthropos and Humanitas: Two Western Concepts of Human Being.” In Translation, Biopolitics, Colonial Difference, edited by Naoki Sakai and John Solomon, 259–73. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Rancière, Jacques. 2009. “Contemporary Art and the Politics of Aesthetics.” In Communities of Sense: Rethinking Aesthetics and Politics, edited by Beth Hinderliter, William Kaizen, Vered Maimon, Jaleh Mansoor, and Seth McCormick, 31–50. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Sahni, Kalpana. 1997. Crucifying the Orient: Russian Orientalism and the Colonization of Caucasus and Central Asia. Oslo: White Orchid Press.

Schapov, Afanassy. 1906. Sochineniya (Writings). Saint-Petersburg: M.V. Pirozhkov.

Scheglov, Ivan. 1993. Khronologichesky perechen vazhneishikh dannykh iz istorii Sibiri: 1032–1882 (Chronological List of the Most Important Data of Siberian History: 1032–1882). Surgut: Severny Dom.

Tekuyeva, Madina. 2006. Muzhchina i Zhenschina v Adygskoi Kulture (Man and Woman in the Adygean Culture). Nalchik: El-Fa.

Tlostanova, Madina. 2010a. Gender Epistemologies and Eurasian Borderlands. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

———. 2010b. “A Short Genealogy of Russian Islamophobia.” In Thinking through Islamophobia: Global Perspectives, edited by S. Sayyid and Abdoolkarim Vakil, 165–84. London: Hurst & Co.

Tlostanova, Madina, and Walter D. Mignolo. 2012. Learning to Unlearn: Decolonial Reflections from Eurasia and the Americas. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Press.

Tokhtakhodzhayeva, Marfua. 1999. Mezhdu Lozungami Kommunizma i Zakonami Islama (Between the Communist Slogans and the Islamic Laws). Tashkent: Women’s Resource Center.

Yerofeyev, Victor. 2000. Pjat Rek Zhizni (Five Rivers of Life). Moscow: Podkova.