• 5 •

Production Costs and Issues

Of the many obstacles that confront the small farmstead cheesemaker, finding insurance, dealing with labor issues, and facing the reality of product loss are often not considered until they are staring you in the face. This chapter will help you learn about choices and options regarding these three topics that will help you make good, cost-effective decisions for your business.

Insurance for the Farmstead Creamery

Believe it or not, I know some commercial dairies that are operating without any insurance, either for the property or for product liability. Without proper farm and liability insurance, you place your entire investment and future at risk! It takes only one lawsuit or incident (even if you are not at fault) to, as the old cliché goes, lose the farm. Please keep in mind that all of the information presented in this book is intended to be used as a guide, not as legal advice and counsel. You will want to thoroughly investigate the options and requirements particular to your state and situation. The information contained here is subject to change and should not be considered complete.

Farm Insurance

Just what is farm insurance? Most farm policies offer comprehensive coverage that takes into consideration all facets of a small farm, including the reality that you will probably live on the premises. You will work with an agent to analyze your coverage needs, including land and buildings; products (loss and liability); personal and commercial property, including animals and feed; automobile; employee and visitor liability; and medical (as well as anything else that has personal or commercial value and/or risk).

When we were first seeking coverage, we wanted to keep the current policies we had for our automobile coverage. We had been insured by the same company for decades and were always pleased with the service and premium. But we were not able to use that same company to insure the farm, as they did not offer dairy farm coverage. (Many companies will insure horse or hobby farms, but not commercial dairies, no matter how small!) We looked into splitting the policy, with our old insurer covering auto and the new one covering the farm, but it was pointed out to us that, as a family farm and residence, everything we owned could be linked to the business in the event of injury, loss, or liability.

Pholia Farm’s washed rind cheese Wimer Winter aging.

The following are descriptions and examples of some of the possible areas you will need to consider for coverage. Remember, this is a guide only, not legal advice or opinion.

Product Liability

Sometimes called “food insurance,” product liability insurance does just what it sounds like: it provides coverage, to the limit of the policy, from damage caused to others by your products. Most retail venues (such as grocery stores, cheese counters, and even some farmers’ markets) will require you to have minimum product liability coverage of one million dollars. Even if this is not the case with your retail customers, carrying product liability coverage is a good idea. Here are some points to consider when discussing product liability:

• Annual product sales (estimate in the beginning)

• Level of coverage needed

• Prior claims

• Quality assurance or HACCP plan (see chapter 12)

• Type of cheese (here they will want to know if it is raw-milk cheese)

General Liability

General liability provides coverage for injuries and property damage related to your farm. This includes employees, interns, visitors, and volunteers. You will need to address the following:

• Number of employees

• Interns (include details, such as housing and duties)

• Events you hold where visitors would be present

• Precautions you will take to ensure safety

Commercial Property Coverage

This category will include the following areas:

• Buildings used in your business

• Property, such as cheesemaking and office equipment

• Business income, to cover loss of income as put forth in the policy

• Agricultural equipment (tractors, trailers, etc.)

• Animals, hay, feed

Personal Property Coverage

As in a homeowner’s policy, this coverage is for personal residence and structures, furnishings and belongings, and so forth.

Automobile Coverage

Each vehicle you drive will likely be considered commercial, even if you don’t plan on using it for business. The reasoning is that if your designated business auto breaks down, you will probably use another vehicle you own. Remember, you are engaged in business even when you take business mail to the post office. The good news is that usually a policy that bundles so many areas together is relatively affordable (as compared to purchasing each component separately).

Finding a Company and an Agent

This can be quite a challenge—especially if the phrase “raw milk” is involved. Even though raw-milk cheeses are legal, they still raise a red flag for many insurers. If you know other cheesemakers in your state or area, you can talk to them about who they use, and whether they are satisfied with them. Some states’ agricultural departments maintain a list of companies that provide farm insurance, but many of these providers focus on crop farms and not dairy farms. Agricultural newspapers often have ads as well, but, again, the majority do not necessarily cover farmstead cheese operations. Another very good place to find a company is farm/agricultural expositions. Quite often insurance providers will have a booth at such events.

A local agent is a must, in my opinion. Our first agent, who was some distance away, was recommended by another cheesemaker in our state. I tried to find a local agent at that time who could write policies from the same provider as the long-distance agent, but without success. When we finally located a local agent and switched, our policy became more pertinent (and even a bit less expensive). We also felt more satisfied with the service. Remember, you can have an agent visit your farm before you sign a policy. He or she will be working for you, so take the time to interview and find the right match. The complexity of the whole farm policy requires a good working relationship with the agent and frequent reassessment for updates and changes.

The complexity of the whole farm policy requires a

good working relationship with the agent and frequent

reassessment for updates and changes.

What Will It Cost?

I wish I could tell you! Everyone’s policy will vary greatly. But you can start your estimate at $350 to $550 per month for a small creamery. Remember to reassess your policy on an annual basis. It is possible that reductions can be made the longer you are insured without incident. Here are some pointers:

• Read the policy yourself and look for coverage that is not needed or that is missing.

• Consider higher deductibles for items that you believe are low-risk or that you can afford to cover out of pocket.

• Don’t make claims for small-value items; remember, every claim will be taken into consideration when you are renewing your policy.

• Shop around!

Health Insurance

Many small farmers in the U.S. work and run their farms without health insurance. The high cost of individual policies is quite prohibitive. It is hard for many of us to contemplate spending hundreds of dollars each month on something that we may never need—to the extent of its coverage—when everywhere we look on our farms there are real, everyday problems that those same dollars would solve: a new roof on the barn, a new pump for the well, a ton of hay for the animals. But don’t fool yourself: uninsured farmers are playing a game of chance. Some will win, but others will lose—and by lose I mean lose everything they have worked so hard to build, including that barn with its new roof.

Uninsured farmers are playing

a game of chance.

The best wisdom I’ve heard on this topic was shared by Marion Pollack and Marjorie Susman of Orb Weaver Farm in New Haven, Vermont. For them, the health insurance bill is always paid first, no matter how tight the budget might seem at the time. They understand that it would take only one incident, even the breaking of a leg, to financially cripple the entire operation. When all of your assets are tied up in one property and one livelihood, risking its loss by not having health insurance is an unwise business decision.

Many farmstead cheesemakers rely upon insurance coverage provided by the employer of a spouse who works off the farm or, as in our case, health-care coverage from military retirement.

At the writing of this book, several hopeful cooperative health insurance plans are in the works, including one through the American Cheese Society. Other organizations in various parts of the country offer members health insurance options as well, including the Farmers’ Health Cooperative of Wisconsin, the Agri-Business Council of Oregon (there are branches in many other states, but as far as I can determine, only Oregon’s offers a group health insurance plan), and Agri-Services Agency. With health insurance being on the forefront of the political agenda at the moment, it is possible that there will be better access to care for all farmers in the near future. At the moment, though, it is costly and difficult to find.

Life Insurance

As a small business that likely relies on only a few people (usually family members) for all aspects of operation, the loss of one of these key members can mean the loss of the business. Sit down with your business partner(s)—husband, wife, mate, etc.—and do your best to try to realistically calculate the amount of funds needed should one of you die. While of course no one can put a price on replacing a lost loved one, a certain amount of money can help you weather the loss and eventually recover—from a business standpoint—without significant damage to your business. The good news about life insurance is its affordability, especially when compared to health and farm insurance!

When choosing life insurance coverage, ask yourself a very basic question: “If my partner died, how much money would I need to keep the farm, the business, and the family going?” Consider the following possible costs:

• Funeral and burial, or alternative life-end, costs.

• Hiring help to replace lost labor (don’t forget things like cleaning, cooking, and child-rearing).

• Debt and bills previously paid by the lost family member’s financial contribution.

• Lost benefits, such as health insurance, retirement pay, etc.

Even if you believe you would sell your farm and business should your family partner die, you will still have costs associated with the transition that could be difficult to cover.

Good Help Is Hard to Find: Labor Issues

Here comes the topic that brings the most frustration to the very small farmer—finding reliable and competent workers. The nature of the life of a dairy makes it inherently difficult, with milking taking place at 8- to 12-hour intervals and the unpredictability of animal behavior. Of all of the issues facing the small dairy person, finding good help seems to be the most perpetually frustrating. In my interviews, the only people I came across who had not experienced dissatisfaction with farm help were those who didn’t use any.

The only people I came across who had not experienced

dissatisfaction with farm help were those who didn’t use any.

Employees or Interns?

Many small dairy farmers find the concept of an intern very appealing. Who wouldn’t? In theory, it’s a win-win: trading work experience for labor. But be warned: state and federal labor laws still apply to this relationship, and lawsuits have been brought in the past due to dissatisfaction on the intern’s part. This section will cover the basics, but it is not meant to be a complete guide to legally employing and engaging labor of any kind. Be sure to consult with your labor office, lawyer, bookkeeper, or other pertinent and up-to-date resource.

TIPS FOR SUCCESSFUL INTERNSHIPS

1. Clearly define and support (with documentation or other evidence) the monetary value of room and board.

2. Document hours spent on non-agricultural work, such as packaging product and selling at farmers’ markets, for accurate tax reporting and compensation.

3. Clearly define educational goals and how they will be attained by the intern.

4. Document time spent on educational instruction and subject(s) covered.

5. Structure stipend or wages in a tiered approach, with a greater educational component in the beginning of the internship and lessening toward the end.

6. Provide social opportunities for solitary interns during their off time.

What’s the Difference?

While in practice interns are often treated very differently from employees, the law recognizes very little difference. Interns exchange their labor (usually seasonal) for housing, food, and, most importantly, hands-on education. In addition, they are almost always paid a stipend. Employees, on the other hand, exchange their labor for cash wages. In both cases, federal and state labor laws apply. You as the employer could be held responsible, in the eyes of the law, should your workers—employees and interns alike—have a grievance with your employment practices. Remember this and protect yourself, even if at the time it seems like more trouble than it’s worth.

You as the employer could be held responsible, in the eyes

of the law, should your workers—employees and interns alike—

have a grievance with your employment practices.

So given the complications, why would you choose an intern over a traditional employee? It seems that the best intern relationships come when there is an underlying desire to teach and share on the part of the farmer-cheesemaker. When that desire is paired with a worker whose primary motivation is not to earn but to learn, then a mutually beneficial and satisfying relationship can occur.

Legal Considerations

• Internal Revenue Service rules for reporting compensation and withholding taxes. Download or send for the “Agricultural Employer’s Tax Guide” (www.irs.gov/publications/p51/index.html). You will need to report all compensation (including meals and housing), but you will not have to withhold taxes on the value of room, board, or other non-cash wages. If you employ a bookkeeper, be sure he or she has a copy of this guide, as rules for agricultural workers are often unique.

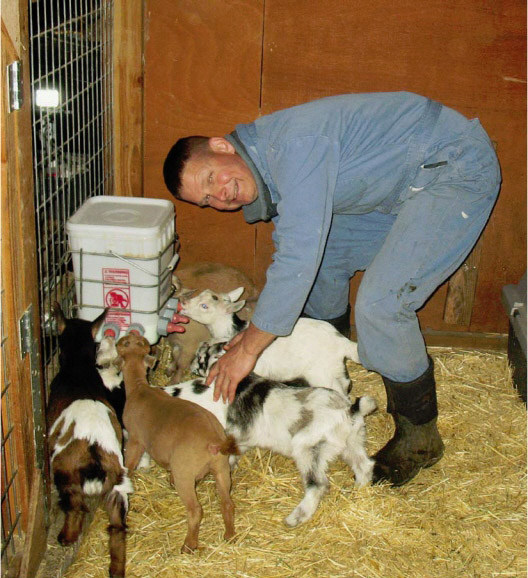

On most small farms, family members provide the majority, if not all, of the labor. Here Vern Caldwell, the author’s husband, feeds young kids at Pholia Farm, Oregon.

• Federal minimum wage law. While most small farms are exempt from the federal minimum wage law, you should review the Fair Labor Standards Act as it applies to agricultural employers. It covers other issues, including overtime rules and “non-agricultural” work that takes place on or off the farm. For example, selling at a farmers’ market is not considered agricultural work, and the federal minimum wage law would apply. (In 2009 the federal minimum wage was raised to $7.25 per hour.)

FRAGA FARM

Jan Neilson of Fraga Farm in Sweet Home, Oregon, has a very well-thought-out intern and employee program. Her two part-time employees and the occasional intern are all on payroll (done by a bookkeeper once a month, costing Jan only about $25.00). The intern’s work is divided into hours spent doing agricultural work (such as milking and feeding) and non-ag work (such as farmers’ markets and packaging of product). From the intern’s gross pay are deducted the non-cash compensations (such as room, board, and education). Then taxes, Medicare, workers compensation, etc., are withheld. It sounds complicated, but with the help of a good bookkeeper, Jan was able to set up a legal and fair program that allows her to have the workers without the worry.

• State minimum wage laws. A few states have minimum wages that are higher than the federal level. In addition, some require that minimum wage be paid to all farm workers. Check with your state labor board.

• State compensation laws. States will vary in how they view compensation such as room and board. Some will allow you to set the value of the compensation, while others stipulate an amount.

• Workers compensation laws. Go to the U.S. Department of Labor’s website (www.dol.gov) and follow links for the Employment Standards Administration (ESA) and the Office of Workers Compensation Program (OWCP) to find a link to your state’s office. Again, states vary in their laws, so be sure to investigate thoroughly.

• Educational component. If you can thoroughly document that your training program will truly educate and benefit the trainee, this can be a form of non-cash compensation, provided that both parties have agreed on its value.

• Work agreement. However you decide to structure your internship or employment program, a mutually agreed upon and signed work/ internship agreement is highly recommended—and in most states it is a requirement.

For more thorough information on setting up successful internships, I recommend the following reading:

1. Internships in Sustainable Farming: A Handbook for Farmers, by Doug Jones, published by the Northeast Organic Farming Association. Available at http://nofany.org/publications.html.

2. Western Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education (SARE) Farm Internship Curriculum and Handbook, by Tom and Maud Powell and Michael Moss. Available at http://attra.ncat.org/intern_handbook.

PHOLIA FARM

Every year we have had something happen that has caused the loss of up to 10 percent of our annual production. One year it was inadequate cooling in the aging room (it didn’t cause us to lose cheese, but we had to shut down production for a week to rebuild the aging room); the next year it was cheese mites (these are normal on long-aged cheeses but have to be kept at a minimum or they cause severe aesthetic and flavor defects). Another year we lost several months’ worth of cheese to poor quality due to high milk urea nitrogen (MUN) levels in the milk (caused by overfeeding of a certain type of protein). The lesson for us was to be more alert at all stages of the process, to keep learning, and to learn to accept the occasional “glitch” in income.

3. “Agricultural Employer’s Tax Guide,” published by the Internal Revenue Service. Available at www.irs.gov/publications/p51/index.html.

Having interns can either be a very rewarding experience or it can be a very frustrating one. The cheesemakers I interviewed across the U.S. had experienced the entire gamut, from satisfaction to knowing someone who had been sued by a former intern. The same is true of employees. The best advice is to understand the legal requirements, structure your program to fairly meet both your and the intern’s goals, and document that program. And finally, don’t have any second thoughts about investing in the services of a good bookkeeper. Do you really have the time, skills, and interest that is required to keep your farm’s financial side in order? A few hours’ work a month by a competent bookkeeper is usually all it takes to keep a small farm’s payroll and books in good shape.

Don’t have any second thoughts about investing

in the services of a good bookkeeper.

Product Loss

Your first business plan will include income projections based on how much milk you will have and how much cheese you will make from that milk. While in theory these numbers should work, in reality you will likely have a significant amount of waste—from milk lost due to equipment failures; milk quality issues (such as bacterial and somatic cell counts); and lowered production from sick animals. You may also have waste in terms of finished product—from equipment failures, quality issues, expired shelf life, sampling to the public, and even donations to charities.

Along with lost product will often come additional costs related to the reason for the loss, such as replacing and repairing broken equipment (that led to lost milk), treating sick animals (that caused poor milk quality), and product and milk testing (to identify the reason behind the poor milk quality). When creating your business plan, it is a good idea to factor in a percentage of product waste and to budget in a contingency fund for such occasions.

Product sampling at farmers’ markets, open houses, and special events can quickly eat through a small chunk of your inventory. For example, if you are providing cheese for an industry event (let’s use the American Cheese Society networking breaks as an example), you might calculate ¼ to 1 ounce per person, depending upon the total volume of cheese provided. If 400 people are expected to attend, you might need to contribute anywhere from 6.25 to 25 pounds of cheese. At farmers’ markets and open houses, people will probably want to sample each cheese you present. One suggestion is to feature fewer varieties at such events and rotate the types; for example, one week sample out two types and the next week use two different varieties. This can both keep your sample “waste” down and also provide an enticement for shoppers to return to your booth weekly.

Author’s daughter Amelia giving out Pholia Farm cheese samples at the local public radio station’s annual fund-raising cheese and wine tasting event.

Dealing with requests from charities for product donations can be awkward for the new cheesemaker, and even for some of us who have been at it for a while! I suggest budgeting a certain amount of cheese (either in pounds or percentage of annual production—think of it as a “cheese tithe”) to charity. You can either dedicate this to causes you find personally gratifying or choose from among those that contact you. Count on being contacted regularly by many causes, and be ready to explain your policy. Most of these callers will be grateful to not be “strung along” and to know immediately whether or not you will be able to support their event. Here is approximately what we tell new callers: “Your event sounds really worthwhile, but because of our production size we have had to limit our cheese donations to just the few events that we are currently supporting.” If you would still like to help them, you can offer to sell them product at wholesale.

From insurance of all kinds, to payroll, to planning for lost product/income, farmstead cheesemakers face many hurdles during the development and growth of their business. Try to remember that these challenges will seem far less daunting after a while. Seek advice and help from industry and regulatory experts as well as other cheesemakers whom you respect, and, most of all, try to keep in mind that being prepared and planning things out for the worst-case scenario will help protect your future as a farmstead creamery.