• 12 •

Safety: Why “It Hasn’t Killed

Anyone Yet” Isn’t Good Enough!

I have to admit, it took us a few years to get around to even trying to create a HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) plan. It is a daunting task made more difficult by a lack of clear, simplified instructions. Many publications on the subject are designed for the large-scale industrial dairy, not the little creamery operated by only a handful of people. A good portion of the documentation steps in a formal HACCP plan are meant to track the performance of a crew of workers, making these steps seem like wasted time and effort for the very small creamery. Indeed, the plethora of steps and paperwork is very likely to discourage many from attempting to create a solid food safety plan. With that in mind, I have simplified the process for those who would like to get started with HACCP. Should you become interested in a more complex and thorough program, resources listed in appendix A and in the notes/references section will provide much more in-depth discussion of the topic. The subject of product recalls—a part of any good quality assurance plan—is also dealt with in this chapter. While recalls are something we can hope to never experience, the reality is that you or someone you know will probably have to deal with one at some point. The old saying “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” definitely is pertinent when it comes to quality assurance programs!

What Is HACCP?

HACCP (pronounced with a short “a” as in the word “at,” with a soft “c”: “HA-sip”) stands for Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points. In a nutshell, HACCP is a system designed to define every step of a product’s manufacture, identify the points in the process that are critical for food safety, and create a plan that delineates and documents safe manufacturing processes. It is a preventive program, focusing on the process rather than on product testing. An important difference to note: HACCP is not about quality as it relates to aesthetics—taste, texture, aroma, etc.; it is only about the safety of the product.

THE SEVEN PRINCIPLES OF HACCP

1. Conduct a hazard analysis

2. Determine critical control points

3. Establish critical limits

4. Establish monitoring procedures

5. Establish corrective actions

6. Establish verification procedures

7. Establish record-keeping and documentation procedures

In the United States, HACCP programs are mandatory in certain food industries, such as seafood and fruit juices. At the time of writing this book, they are not required in the dairy industry, but they are encouraged. Furthermore, larger dairy processors are usually required by their clients to have HACCP plans in place. Even if you do not create an in-depth HACCP plan, you can still use the principles of HACCP to create your own quality assurance program.

HACCP is not about quality as it relates to aesthetics—taste,

texture, aroma, etc.; it is only about the safety of the product.

Before a HACCP plan is developed, you must first define your “prerequisite programs.” What is often confusing is that while prerequisites must be defined as a part of building a HACCP plan, they are not part of the seven official principles of HACCP as defined by the National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods (NACMCF).

Alyce Birchenough checks and logs the pH during her cheesemaking process as a part of Sweet Home Farm’s quality assurance program.

To further add to the bewilderment, there are steps in prerequisite programs—as outlined by the Dairy Practices Council’s Guideline No. 100, “Food Safety in Farmstead Cheesemaking”—that overlap steps and principles in HACCP.

To help make all of this easier to understand and to encourage the creation of a quality assurance program that even the smallest cheesemaker can implement, I have simplified and combined prerequisite programs and the seven HACCP principles into three steps.

Three Steps for Creating a Quality Assurance Program

1. Prerequisite Programs: These are standardized procedures based on knowledge of proven facts regarding the safe manufacture of a food product. They include Product and Process Information, Standard Sanitation Operating Procedures (SSOPs), and Good Manufacturing Processes (GMPs).

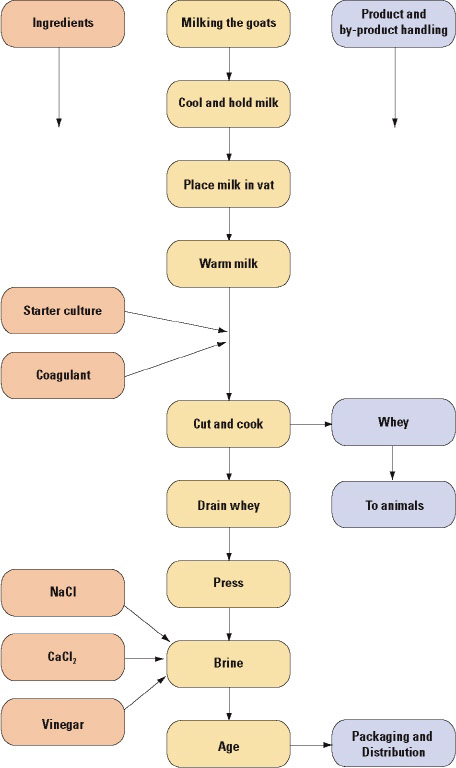

a. Product and Process Information: Includes a description and a flow chart (showing every step of the process) for each cheese made.

b. SSOPs: List step-by-step proper cleaning and sanitation of equipment and facilities.

c. GMPs: List procedures for maufacturing related to facility, equipment, and processes.

2. Hazard Analysis: Each step of your process is analyzed for any chemical, biological, and physical risk associated with that particular step.

3. Critical Control Points (CCPs): These are points during the process when a “control” (think a step, a procedure, etc.) is used to prevent, limit, or eliminate a critical food safety hazard.

To sum it up, the basic principle of HACCP is this: All hazards (identified in Step 2, Hazard Analysis) are controlled, whether through Step 1 (Prerequisite Programs) or Step 3 (Critical Control Points). If you have identified everything that could possibly go wrong and you develop procedures to prevent all of these potential problems, then the odds are very good that you will be producing a safe product.

The foundation for a good HACCP plan is knowledge. Until you are well educated in the microbiology and chemistry of the cheesemaking process, including cleaning and sanitizing, you cannot adequately understand or foresee the potential hazards that exist. This is another reason that even the most talented, intuitive cheesemakers should seek ongoing education about their craft!

Until you are well educated in the microbiology

and chemistry of the cheesemaking process, including

cleaning and sanitizing, you cannot adequately understand

or foresee the potential hazards that exist.

So let’s assume you are a fairly experienced cheesemaker with some education regarding milk chemistry and cheesemaking microbiology. In addition, you have books and publications that delineate good cleaning and sanitation, basic good manufacturing processes, and risks and hazards associated with taking raw, living milk and turning it into a fermented food. Where do you start?

Step 1: Prerequisite Programs

Step 1a: Flow Chart and Product Description

Creating a flow chart for each cheese you make (start with just one for now) is the most logical starting point for most cheesemakers. The flow chart falls under the “Product and Process Information” portion of the prerequisite programs of HACCP. When creating the chart, be sure to list every step of the process, any added ingredients (in addition to milk), and the product and by-product distribution.

You can also include a more complete description of the cheese that includes the following:

• Common name: Does the cheese fall under a Federal Standards of Identity* description?

• Commercial name: What do you call it?

• Packaging: How is it packaged?

• Labeling: How is it labeled?

• Shelf life: What is the shelf life after sale?

• Storage temperature: What is the correct storage temperature?

Here is an example using one of our cheeses, Elk Mountain:

Common name: None

Commercial name: Elk Mountain

Packaging: Sold in whole or cut wheels wrapped in freezer paper and/ or plastic wrap

Labeling: Handwritten on paper with name and date of make

Shelf life: 4–6 weeks, depending on size of cut

Storage temperature: Aged 6–9 months at 55°F; storage after aging, 38°F

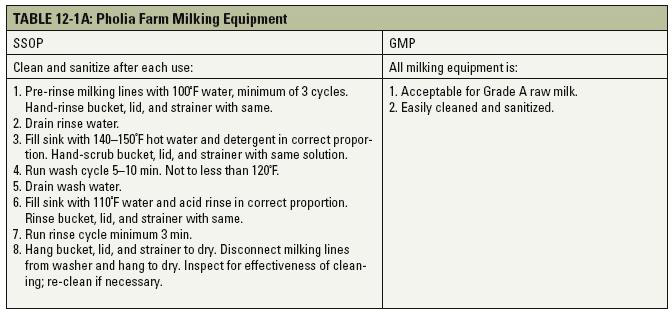

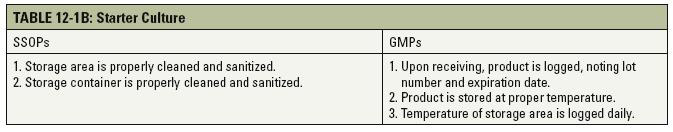

Step 1b: Standard Sanitation Operating Procedures (SSOPs)

SSOPs deal with the proper cleaning and sanitizing of everything in your dairy and creamery, including workers’ hands, processing equipment, floors, refrigerators, and raw material.

Flow chart for Pholia Farm Creamery’s Elk Mountain cheese.

SSOPs—Things to Remember

1. You cannot sanitize something that is not clean; therefore proper cleaning is as important as proper sanitizing.

2. Proper dilution of detergents and sanitizers must be coupled with proper water temperature, scrubbing, and length of time cleaned to be effective.

3. Sanitizers not diluted to the proper concentration will be ineffective if weak and leave residue (a chemical hazard) if too strong.

4. Good SSOPs include documentation of cleaning frequency and descriptions of cleaning protocols and who will do the job.

5. To be effective, SSOPs must be monitored and corrections made—choose a very reliable person (probably yourself ) for this job.

SSOPs—The “Big Eight” Sanitation Concerns

1. Safety of water that comes into contact with cheese (such as in washed-curd cheeses) and with cheese contact surfaces (vat, molds, etc.).

2. Condition and cleanliness of cheese contact surfaces, utensils, gloves, etc.

3. Prevention of cross-contamination between finished cheese and raw products, utensils, packaging, etc.

4. Prevention of adulteration of cheese, cheese contact surfaces, utensils, gloves, packaging, etc., with chemical hazards, such as cleaning compounds and lubricants; physical hazards, such as bandages, fingernails, jewelry, and pests; and biological hazards.

5. Maintenance of hand-washing and toilet facilities (this includes single-use towels and hot water).

6. Correct labeling and storage of all chemicals.

7. Control of worker health conditions that could cause contamination of cheese, packing materials, surfaces, etc.

8. Exclusion of pests and pets from dairy and creamery.

Step 1c: Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs)

GMPs deal with policies regarding the production of cheese as it relates to everything in your dairy and creamery, including hygiene, quality of equipment, construction of floors, quality of refrigerators, and documentation of raw materials. GMPs are a part of the Federal Code of Regulations (see resources in appendix A).

GMPs—Four Main Areas of Food Processing

1. Personnel hygiene includes policies on hand-washing, jewelry, eating in manufacturing areas, illness, cleanliness of clothing, etc.

2. Building and facilities includes lighting and ventilation, hand-washing stations, pest management, etc.

3. Equipment and utensils must meet food-grade standards and be easy to clean, sanitize, and maintain.

4. Production and process control includes time and temperature logs, records on ingredients, lot identification of cheeses, etc.

Common chlorine strength test strips.

Comparing SSOPs to GMPs

To better help you understand the difference between an SSOP and a GMP, table 12-1 presents two examples, one using milking equipment and one using starter culture. You can see how the two prerequisite programs overlap in many subject areas, but the focus of each is different. When used together, a complete process that creates a safe product is the result.

Putting the Prerequisites Together

Once you understand the goals and parameters for SSOPs and GMPs, you are ready to document them in your prerequisite program. I have seen this done a couple of ways. Some people write a narrative for each step of the flow chart that describes each process and states what SSOPs and GMPs apply. Others document a full set of SSOPs and GMPs in a binder. During Step 2 of creating a quality assurance program (Hazard Analysis) you can refer either to the narrative that follows the flow chart or to your prerequisite program binder. If you skip the creation of a well-documented prerequisite program, you can still complete the hazard analysis, but it will be less thorough and—even more important, perhaps—less impressive and persuasive should you ever find an FDA official at your doorstep.

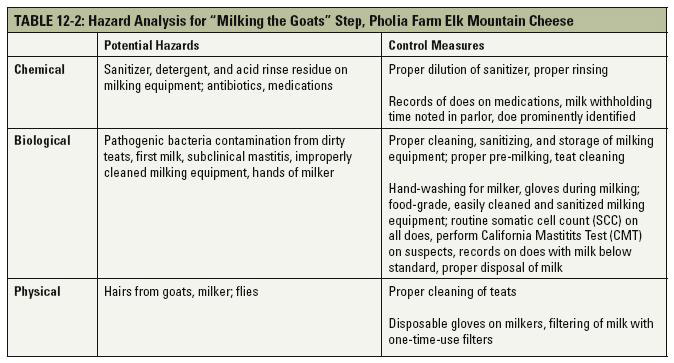

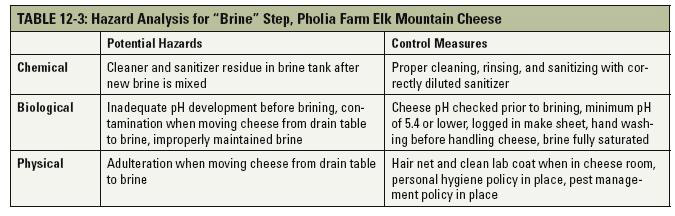

Step 2: Hazard Analysis

Once you have your flow chart and are comfortable with the standards for SSOPs and GMPs (keep reference books and publications on hand to help with the process) you will be ready to analyze each step of your process for hazards in three categories:

• Chemical—examples include antibiotics, sanitizers, pesticides, paint, and allergens.

• Biological—examples include pathogenic bacteria, such as Listeria and E. coli; viruses, such as hepatitis A; and mycotoxins from mold.

• Physical—examples include bandages, fingernails, disposable glove fragments, glass, and pests.

The Dairy Practices Council’s Guideline No. 100, “Food Safety in Farmstead Cheesemaking,” contains very thorough lists of potential hazards in the above categories. In addition, it covers SSOPs and GMPs as they relate to reducing and/ or eliminating the risks posed by these hazards. It is an inexpensive publication well worth having.

So let’s take a couple of steps from the flow chart for Elk Mountain cheese and analyze them for risks.

Remember, when you are working on control measures for each step, measures must deal with safety only—not quality as it refers to taste, texture, aroma, etc. A good HACCP plan does not mean a tasty cheese, only a safe one!

Step 3: Identifying Critical Control Points (CCPs)

This part of the HACCP process always confused me. I wondered why you would need to identify additional hazardous points if you had created a sound prerequisite program. If your SSOPs and GMPs dealt with all of the hazards you could identify, why would you need to label certain areas with a CCP? It didn’t make sense to me, until I understood the difference between control measures (also called control points) and critical control points:

• Control measures are points in the system where loss of control may result in a reduction of product quality, but not a reduction in the safety of the cheese.

• Critical control points are points in the system where a control must be exerted or food safety will be compromised. CCPs represent a point in the process where no other measures that will occur later can eliminate or mitigate the hazard.

So think of CCPs as a kind of red flag or highlighted control measure. Examples of CCPs in the cheesemaking process are pasteurization, acidification, salting, and aging. Once you have done your hazard analysis, you can go back through the points and mark as CCPs those that present a critical risk. Once you have determined where the CCPs are in your process, it is important to set parameters and document that they have been met. This is the whole point of HACCP.

Is a Recall in Your Future?

A cheesemaker I once interviewed (who is no longer in business) gave me a provocative quote: “If you stay in business long enough, you will have a recall.” Stories abound regarding recall nightmares, some with happy outcomes and others from which companies could never recover. Even the ones with a happy ending were stressful and costly while they were happening. If you have developed a good HACCP or other quality assurance plan, you will have a very good chance of surviving an FDA-requested recall; if you do not, then the odds are not as good. In addition to the HACCP plan, you should have a recall plan—indeed, it is considered a part of a complete prerequisite program.

FDA RECALL CLASSIFICATIONS

Class I: There is a strong likelihood that use of, or exposure to, a product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death. (For example, contamination with pathogenic bacteria or Class I allergens not declared on a label.)

Class II: Exposure to, or use of, a product may cause temporary or medically reversible adverse health or consequences or where the probability of serious adverse health consequences is remote. (For example, contamination with a piece of glass.)

Class III: Exposure to, or use of, a product is not likely to cause adverse health consequences. (For example, a product that contains an ingredient that is safe but is not declared on the label.)

Recalls Defined

Be wary of the use of the term “recall.” It should be used only when a product poses a risk hazard as defined by the FDA guidelines (see sidebar). Use it only when an FDA-requested, or FDA-instigated, recall is taking place. Products can be brought back from customers under a “market withdrawal” plan. When you read the classifications in the sidebar, please pay close attention to Class III. Even at this lowest level of FDA recall your business could be at risk for something so seemingly simple as putting the wrong label on a cheese!

RECALL STEPS

1. Contact lawyer and FDA: If you discover cause for a true recall (your situation meets the criteria listed in the sidebar on FDA recalls), contact your lawyer and the FDA.

2. Contact retailers, wholesalers, and distributors and arrange to have your products returned. Follow this initial contact with a formal recall notice (see step 5).

3. Obtain samples and send them to an independent lab for testing (if the FDA instigated the recall).

4. Public notification (press): only if the product poses a serious health threat, i.e., Class I.

5. Recall notice: Create a notice that identifies the product (lot number or other identifier), the reason for recall, who to contact at your company, what to do with the recalled product, and reimbursement procedures.

6. Terminate the recall after all product has been accounted for and after consulting with the FDA.

What Can You Do to Prepare Right Now?

There are several fronts on which you can prepare for the potential of a recall. All of these steps are sound business measures—even without fear of a recall—so implementing them, regardless of how safe you feel, is still a great idea.

Preventive Measures

1. HACCP: Nothing will help set the stage for your defense better than a sound HACCP plan!

2. Product identification in-house and tracking: Identify each batch of cheese on your make sheet/log and track it through its aging, packaging, and sale. This step is essential in order to perform a successful recall or market withdrawal.

3. Shipping records: This follows product identification.

4. Company contacts: Know who to contact for each retailer, wholesaler, or distributor that sells your cheese.

Drills

Hold a mock recall, go through all the steps below, and see if you are confident that each step can be completed with relative ease. Remember, if a recall situation arises, the stress level will be high and responsibilities that would seem simple under normal conditions become challenging.

There, you’ve made it through a tough chapter on topics that are all about the harsh realities of running a business that produces what is thought of as a high-risk product. Even if you are not ready to implement a quality assurance and recall plan right now, keep it in mind and take the time—even if you do it in stages—to create what I like to call your “business armor.” You have already put a lot of thought, time, and, no doubt, money into this venture; you might as well take the extra steps to protect it for the long haul.

*Federal Standards of Identity for dairy products lists products with production standards that must be met for that cheese or dairy product. If you make a cheese that falls under any of these descriptions, you must meet the production criteria for that product, and it must be labeled accordingly. (For more on the Federal Standards of Identity, see chapter 3.)