Fictional films set in institutions invariably feature scenes of violence, suicide, cruelty or escape, which seems inconsistent with the usual orderliness of real life institutions. Inevitably, however, the excessive control that pervades the on-screen institute leads to visual chaos and narrative disruption. These traits seem universal to the American institution film, the ‘institution film’ being, for the purposes of this book, one in which the institution is central to narrative organization. Indeed, such patterns of transgression appear regularly throughout the genre’s well-established history, especially in films set in asylums and prisons. It is therefore relevant to diverge from typical Foucauldian analyses of the institution, which tend to focus on order, regulation and panoptic modes of surveillance, to a theoretical model that centres on the implications of repression. Julia Kristeva’s theory of abjection1 provides such a model, which I utilize in this book to explain how fictional institutions order space. Since this approach challenges Foucauldian perspectives, I also consider any tensions that arise between these two apparently opposing viewpoints.

In general, the chaos that emerges in fictional institutions is a consequence of attempts to regulate socially, remould, or ‘break’ the identity of the inmate. Sometimes this is achieved through seemingly innocuous regimes of drug administration, or often through more radical measures that may involve overt brutality, extended solitary confinement (the ‘hole’ features regularly in prison narratives) or intrusive surveillance. These aspects are important in providing narrative interest to what would otherwise be mundane and highly repetitive scenarios, though at times they may reflect the practices of real institutions.

In many ways, the filmic institution assumes a parental role, controlling not only the physical body through drugs and prescribed body movement, but also returning the inmate to an essentially infantile psychosexual state. This results from restrictions to conversation, limitations to private space or enforced uniformity of clothing (or even a lack of clothing). Frequently, it stems from the repression of sexual desire. Such suppression of individuality usually leads to inmate resistance and efforts to break away from the institution. Therefore, the institution’s highly repressive and regulated spaces are prone to rupture, with any compromise to identity generally leading to efforts to reclaim it.

These characteristics are typically found in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) directed by Milos Forman, a film that sees its protagonist, Randle McMurphy (Jack Nicholson), a psychiatric inpatient, undergo electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for no apparent good reason. In fact, Head Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher) implements this therapy merely because McMurphy resists her cruel, controlling practices, causing McMurphy to suffer irreversible brain damage. As an act of compassion, Chief Bromden (Will Sampson), a friend and fellow patient, suffocates McMurphy, breaks down the window of the asylum and escapes. His escape signals the culmination of many years of repression within the asylum under the dominating rule of Nurse Ratched. This repression is largely attributable to her inflexible and controlling regime, which she achieves through the administration of various alleged forms of ‘treatment’ such as group therapy, medication and ECT. Ratched further exercises her power through the oppressive surveillance of the patients, but also operates at a more subversive level, regulating their privileges, repressing their libido through drugs and generally suppressing all aspects of individuality. As a result, the patients exhibit infantile characteristics, suggested through various aspects of the mise-en-scène. They are often seen wearing only white underwear, are susceptible to frequent tantrums, and their physical stature and behaviour, especially of Martini (Danny DeVito) and Cheswick (Sydney Lassick), are childlike. Their infantilism is also represented through problems mastering speech; Chief Bromden is apparently ‘deaf and dumb’ and Billy Bibbitt (Brad Dourif) speaks with a pronounced stutter, while the rest of the group seem mostly reluctant to say anything during group therapy sessions.

Ratched manifests as a monstrous version of femininity, signified visually by her twin-horned hairstyle and cold, unblinking eyes. Indeed, in the spectator’s first visual encounter with Ratched, she appears in a flowing black cape and black hat. In marked contrast, McMurphy, who resists her controlling practices, seems humane and compassionate and, despite being a convicted rapist, easily gains the spectator’s sympathies. He remains the sole figure of adult masculinity on the ward, suggested by the fact that he is the only patient to wear his own clothes, a typical means of expressing an individual, gendered identity. His masculinity is also emphasized physically (he escapes by scaling a high barrier), and he has been incarcerated because, as he claims, ‘[he] fight[s] and fuck[s] too much’. Indeed, he becomes a father figure to the other patients and encourages them to engage in experiences that develop their masculine egos. McMurphy is not merely the good father but becomes almost a Christ-like figure, helping the patients overcome their various social inadequacies. Although Ratched’s efforts to control McMurphy and repress his sexuality repeatedly fail, she still exerts a strong influence over the other patients, particularly Billy Bibbitt.

The repression that the patients undergo leads inevitably to points of rupture; either they escape from the institution or are given to irrational, temperamental outbursts or, more significantly, murderous or suicidal actions. These disorderly episodes, however, also generate pleasure and lead to liberating events that encourage masculine activities related to adulthood, such as the fishing trip. The party is another significant occasion at which the patients’ experiences of alcohol and sex, including Billy’s first sexual encounter, transiently transform their lives. These incidents are positive because they alleviate repression; even Billy Bibbitt’s stammer temporarily disappears because of his newfound sexuality. The physical transgression of boundaries also relieves tension, exemplified when McMurphy breaks the glass of the nurses’ station to retrieve Cheswick’s cigarettes in an attempt to pacify him during one of his many tantrums. The violation of the nurses’ station anticipates the final point of release when Bromden hurls a hydrotherapy unit through the asylum window and subsequently escapes. Renewed repression by the monstrous Ratched, however, brings about abjection and chaos, as Billy kills himself and McMurphy tries to strangle Ratched. The narrative revolves around these episodes of repression and transgression, which provide transient relief or pleasure, but also lead to abjection.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest exhibits many features common to the institution film, especially in its inclination to disruption. Apart from such commonalities of theme, figure behaviour and narrative pattern, the fictional institution also tends to possess distinctive spatial qualities. In addition to a system of highly regulated spaces that are subject to various levels and means of control, a network of underground tunnels often underlies the formal, visible architecture, these sometimes resembling the interior convoluted nature of the physical body. In other cases, the labyrinthine workings of the institution may reflect the pathologically or criminally disturbed mind, or the primitive nature of the id. Despite these connotations, however, descent into the underground passages, secret tunnels and sewers of the institution frequently provides a temporary reprieve from the intense surveillance that dominates the upper levels, as well as offering a means of escape. Indeed, escape features prominently in the fictional institution though there are times when the individual becomes institutionalized and is reluctant to leave its comforting security. The desire to escape has parallels with the infant’s desire to separate from the maternal body and again suggests the parental nature of the institution. Overall, these various aspects of the institution film and its tendency for disorder are consistent with Kristeva’s2 theory of abjection, which has multiple meanings but chiefly centres on the abject world of the infant and its subsequent striving for a coherent subjectivity.

Kristeva is one of the key exponents of abjection and discusses its various manifestations in The Powers of Horror as well as in some of her later works. Abjection, according to her, arises from the process of a child becoming autonomous of his or her mother. Rejection of the maternal body constitutes one form of abjection, but the child also begins to recognize and exclude various sources of bodily contamination. These include the detritus of the body, particularly bodily fluids and excrement, but they may extend to other forms of ‘difference’.

Indeed, in this book I contend that the institution film is an obvious site for abjection, with such notions becoming pertinent immediately one perceives the institution as a place that separates normal from other. This exclusion of ‘otherness’ takes place on a significant scale in Western society, with the insane, criminal and sick allocated to specific sites. Despite a recent reversal in this trend, film still makes much of the institutionalization of the aberrant mind and body (though, occasionally, films such as A Beautiful Mind (2001) break with this pattern). It follows that filmic spaces concerned with separating out aspects of aberration, namely the institution, would be appropriate places in which to locate abjection.

Kristeva’s study of abjection has a number of influences. It engages primarily with the earlier ideas of anthropologist Mary Douglas,3 who discusses abjection in the context of the taboos and rituals of ancient cultures. In her seminal work, Purity and Danger, Douglas elaborates on religious abominations associated with ‘unclean’ food, and the ritualizing of certain impure fluids such as blood in sacrifice, as well as the importance of bodily margins, orifices and their vulnerability to impurity. Kristeva incorporates Douglas’s notion of ‘purity and danger’ within her own account of abjection, attributing its source to all that threatens integrity of the self. For Kristeva, this similarly includes the detritus of the body but especially ‘excrement and menstrual [blood]’.4 Like Douglas,5 she further identifies the exclusion of certain foods and religious abominations as ways to sustain a ‘clean and proper body’. The ultimate threat for Kristeva is the corpse;

the corpse, that which has irremediably come a cropper, is cesspool, and death ... if dung signifies the other side of the border, the place where I am not and which permits me to be, the corpse ... is a border that has encroached upon everything. It is no longer I who expel, ‘I’ is expelled.6

She also describes how involuntary bodily actions that arise in reaction to encountering the abject, such as gagging at the skin on the surface of milk, are ways of protecting the self from contamination. Indeed, like Douglas, Kristeva focuses on excluding the abject through maintaining homogeneous boundaries. Consequently, any transgression that ‘disturbs identity, system, order’,7 and that ‘does not respect borders, positions, rules’,8 is liable to abjection. Her delineation of the abject thus includes examples such as ‘the traitor, the liar, the criminal with a good conscience, the shameless rapist, the killer who claims he is a saviour’.9 Maternal abjection is a particularly important facet of her work, Kristeva noting how,

the abject confronts us ... with our earliest attempts to release the hold of maternal entity even before existing outside of her, thanks to the autonomy of language. It is a violent, clumsy breaking away, with the constant risk of falling back under the sway of a power that is securing as it is stifling.10

The ultimate separation is childbirth, Kristeva describing the ‘desirable and terrifying, nourishing and murderous, fascinating and abject inside of the maternal body’.11

Kristeva’s views on the abject feminine body have elicited significant debate in film studies. One of the key theorists relevant to such discussion is Barbara Creed, who examines a number of films, mostly of the horror genre, in relation to what she terms the ‘monstrous-feminine’. She defines certain key areas in which the horror film draws on notions of abjection, namely the soulless corpse, the transgression of the border and the abject mother, but it is the latter that engages the attention of most of her arguments. In her essay about Alien, she describes a mise-en-scène of ‘womb-like imagery’ in ‘the long winding tunnels leading to inner chambers, the rows of hatching eggs, the body of the mother-ship’.12 Creed asserts that the horror of the Alien monster therefore relates to the feminine body and that the abject mother manifests in a number of ways;

she is there in the text’s scenarios of the primal scene of birth and death; she is there in her many guises as the treacherous mother, the oral sadistic mother, the mother as primordial abyss; and she is there in the film’s images of blood, of the all-devouring vagina, the toothed vagina, the vagina as Pandora’s box; and finally she is there in the chameleon figure of the alien, the monster as fetish object of and for the mother. But it is the archaic mother, the reproductive/generative mother, who haunts the mise-en-scène of the film’s first section, with its emphasis on different representations of the primal scene.13

Creed goes on to consider various aspects of ‘the monstrous feminine’ in a range of horror films, including The Exorcist (which Friedkin directed in 1973) and Carrie (directed by De Palma in 1976). While she therefore tends to reduce the abject to negative representations of the feminine body, her work is highly significant, as it has brought the concept of abjection, previously limited to literature and language, into the sphere of popular culture.

Creed is not unique in her connection of spaces of horror with the feminine body. Indeed, uterine metaphors abound in theoretical analyses of film spaces, especially those with negative connotations, which often bring up Sigmund Freud’s study of the uncanny. Freud is another important influence on Kristeva, and her concept of abjection, while primarily drawing on Douglas’s Purity and Danger, also has some obvious parallels with Freud’s study of ‘The Uncanny’.14 ‘The Uncanny’ is one of the most significant works in the field of psychoanalysis concerning uterine metaphors, and usually informs related studies. While Freud identifies different forms of uncanniness, feelings of unease generated by examples such as the ghost, the double, and the automaton, he argues that the original ‘home’, the mother’s body, may also be considered uncanny, or ‘unheimlich’. He suggests that it is a ‘forgotten’ place (through repression of traumatic memories) but still familiar. Because of its association with trauma and castration anxiety, Freud asserts that the uncanny ‘is undoubtedly related to what is frightening – to what arouses dread and horror’.15 In film studies, therefore, there are often links between the uncanny house in film and uterine imagery, with certain spaces having particularly traumatizing connotations, especially the cellar and the attic. These spaces are usually sites of fear, especially in the horror genre, with violation of the home forming part of the genre’s recurring iconography. It is hence logical that theorists such as Creed should also forge links between the horror genre and uterine imagery in discussions of abjection. Indeed, there are numerous cinematic examples of these, including, among many others, The Birds (1963); Girl, Interrupted (1999); L.A. Confidential (1997); Misery (1990); Presumed Innocent (1990); Psycho (1960); Shallow Grave (1994); The Silence of the Lambs (1991); and The Virgin Suicides (1999). Clearly, Freud’s writings on the uncanny are closely aligned with abject space, and several theorists besides Creed16 explore the links between maternal imagery and abject or uncanny space. In one example, Laura Mulvey17 demarcates the cellar as an abject space in her description of Lila’s (Vera Miles) exploration of the Gothic house in Psycho. Referring to the myth of Pandora’s Box as an analogy for inner female space, she asserts that, ‘it is the female body that has come, not exclusively, but predominantly to represent the shudder aroused by liquidity and decay’.18 Also referring to Psycho, Slavoj Žižek19 aligns the three levels of the Gothic house with the id, ego and superego, the cellar representing the id as a repository of basic instincts. Michael Fiddler,20 in his study of The Shawshank Redemption, argues that the prison represents a uterine uncanny space from which Andy Dufresne is reborn. Brian Jarvis,21 like Fiddler, posits the prison as a ‘maternal vessel’22 while Elizabeth Young23 likens abject space to the female body in her analysis of The Silence of the Lambs.

Although there are close associations between abject and uncanny spaces, Freud’s view of the uncanny as a repressed, traumatic memory does not incite the same degree of revulsion encountered in Kristeva’s version of repression. Kristeva herself notes, ‘essentially different from “uncanniness” more violent, too, abjection is elaborated through a failure to recognize its kin; nothing is familiar, not even the shadow of a memory’.24 Furthermore, the abject’s threat of re-emergence requires constant vigilance to keep it in place. This is unlike Freud’s study in which uncanny memories may remain repressed.

However, it is important to note that while bodily fluids and disgust constitute a distinctive and essential aspect of abjection, this is not the sole focus of Kristeva’s use of the term. Despite the tendency for previous filmic analyses to deploy the term ‘abjection’ in relation to the horror and science fiction genres, Kristeva neither limits notions of abjection to the visceral body nor ties it to a particular genre. Rather, for her, the central meaning of abjection emerges in relation to subjectivity and the transition to an adult identity. The use of abjection in this book is therefore distinct from previous interpretations because it considers Kristeva’s concept of the abject in relation to subjectivity and space. Since threat to identity is a consistent theme within the fictional institution, in this book I argue that institutional spaces in film are intrinsically liable to abjection.

Here, the use of the term abjection is distinct in several other ways. For example, Kristeva25 specifies that abjection may be associated with mental illness, in particular during the recovery from borderline personality disorder. Yet studies on the issue of mental illness or abjection in film have not explored this aspect. Second, in this book I directly apply Kristeva’s concept of abjection to the area of theology as well as including an attention to ritual as an essential feature of abject space. These are important areas of Kristeva’s work in which she explains how the Bible and the Virgin Mary26 are closely linked to abjection, stressing the importance of rites to sanctify the abject. A third aspect of abjection that demands closer analysis is racism. This is a significant subject to Kristeva in that she refers to it through the work of Céline and implicates it in several of her other works, including Strangers to Ourselves (1991), and Nations without Nationalism (1993). Although racism as a form of abjection is well documented in the literature, there has been, as far as I am aware, no discussion of its manifestation in the institution film to date.

Furthermore, this study is also distinct in that it broadens Kristeva’s original concept in arguing that old age and end-of-life trajectories are abject. This dimension has clear parallels with an infantile lack of subjectivity, but it is one that Kristeva fails to address and is also an area that film studies has generally neglected.

Finally, while Kristeva suggests that the abject is not only intrinsically fascinating but also essential to the maintenance of subjectivity, previous critical analysis largely tends to ignore this facet. I contend that within the institution film, abject space is generally a site of liberation or catharsis and may therefore have positive effects. Moreover, I suggest that representations of abjection may manifest not only within the mise-en-scène, but also through cinematography, music, language and the use of text. Music and language are important elements of Kristeva’s transition from semiotic to the symbolic (which involves maternal abjection) but have not been considered previously in relation to fictional film or films set in institutions.

In short, I propose a broader application of abjection than has previously been the case. This is not to say that it is a generalized concept or that it may arise in all types of films. Rather, abjection emerges in films in which space, institutions and subjectivity intersect. Because the threat to subjectivity is a significant feature of the ‘institution film’, both through exclusion from society and through restrictions to personal space, dress, sexuality and behaviour, it is an appropriate context in which to consider space as abject.

Fundamental to the institution film and the concept of abjection is the boundary. Boundaries are important to any spatial analysis but are particularly salient to the development of subjectivity, having socio-cultural as well as psychosexual implications. In the context of everyday life, boundary maintenance is intrinsic to the social and cultural development of the individual, and constitutes part of what Norbert Elias27 terms a ‘civilising process’. While Elias describes this process in the broader context of its evolution since the Middle Ages, he also discusses it in terms of the contemporary individual. He explains how self-discipline of the body is learnt through socializing processes adopted from the habits and constraints of the parents, and is usually marked by the passing from infancy through to adulthood. The civilizing process is concerned with repressing certain aspects of the self, predominantly those concerned with bodily function that may incite disgust, as well as public displays of emotion. Elias notes that ‘with this growing division of behaviour into what is and what is not publicly permitted, the psychic structure of people is also transformed. The prohibitions supported by social sanctions are reproduced in individuals as self-controls’.28 The child’s development is discernible in a growing awareness of bodily functions and a sense of shame or privacy associated with these, manifesting in the demarcation of boundaries and the segregation of specific spaces for these functions.

For David Sibley29 too, boundaries are important, though his work deals with exclusion of marginalized groups rather than the activities of the individual. He engages directly with Kristevan theory in the context of peripheral urban space, which he claims is unstable and liable to transgression. Thus, while Douglas and Kristeva’s analyses of the boundary tend to centre on the body and its exclusion of contaminating substances, Sibley extends these ideas to margins and borders within the field of cultural geography. He states that homogeneous, uniform spaces are pure, while peripheral spaces, because of their borderline status, are liable to incursion by marginalized groups that are perceived of as contaminating or dangerous. Consequently, while borders and frontiers are sites of exclusion, they have a tendency to abjection. Referring to Kristeva and Douglas,30 Sibley asserts that

difference in a strongly classified and strongly framed assemblage would be seen as deviance and a threat to the power structure. In order to minimize or to counter threat, the threat of pollution, spatial boundaries would be strong and there would be a consciousness of boundaries and spatial order. In other words, the strongly classified environment is one where abjection is most likely to be experienced.31

He argues that powerful groups attempt to purify space by the construction of socio-spatial boundaries and claims that sites where such separation is difficult ‘create liminal zones or spaces of ambiguity and discontinuity. ... For the individual or group socialized into believing that the separation of categories is necessary or desirable, the liminal zone is a source of anxiety. It is a zone of abjection.’32

In exploring various images of difference, Sibley notes how certain groups have been interchangeably linked together to encompass notions of defilement, and that ‘today, disease, homosexuals and Black Africans have been similarly bracketed together’.33 Moreover, he extends the link between difference and place to that of nature/culture, asserting that ‘relegating dominated groups to nature – women, Australian Aborigines, Gypsies, African slaves – excludes them from civilized society.’34 Sibley also attempts to apply such concepts within a filmic context, citing Taxi Driver (Scorsese, 1976) as an example, wherein prostitutes are a similarly excluded group. His work is not only germane to a study of institutions as sites that also involve exclusionary practices, but also to elements of racism found in one of the films examined in this book.

Part of a child’s development is concerned with recognizing not only the importance of spatial boundaries, but also boundaries the body determines in the processes of sphincteral training and bodily hygiene. Such development relates to what Freud35 terms anal control with psychosexual development being marked by a concern with bodily orifices. He asserts that in the adult, there is a repression of unconscious desires, which are usually of a sexual nature, and these often threaten to re-emerge. The child works through various stages of these archaic desires in its psychosexual development. These include the oral, anal and genital stage. The child must go through these stages and ultimately relinquish its mother to take up his or her normal adult place in society, but may become fixated at any of these stages. In the context of this book, an individual must similarly separate him- or herself from the maternal body of the institution, or work through abjection to achieve a coherent adult identity. Otherwise, he or she may remain fixated at a particular stage of development. Thus, Freud’s description of the relationship between bodily control and subjectivity has commonalities with Kristeva’s36 discussion of abjection.

There are therefore similarities and overlaps between theoretical approaches to the transition from childhood to adulthood and the appropriation of certain socio-cultural habits and rituals. However, Kristeva’s theory has a broader focus on notions of boundary formation. The boundary for her takes account of such diverse subjects as the deviant mind, the borderline personality, the decay of flesh and childbirth. Further, Kristeva’s demarcation of maternal abjection depends on a distinction between what she terms semiotic and symbolic forms, best exemplified through the acquisition of language. According to Kristeva, the semiotic refers to the early stages of the maternal world and the symbolic to the paternal sphere. The transition from one to the other is contiguous with the acquisition of language. This broadening of psychosexual development thus extends well beyond the socializing processes that Elias suggests. While in this book I acknowledge the significant influence of Freud’s work on Kristeva’s study and will engage with it as appropriate, her attention to the border remains central to a consideration of space and subjectivity within the institution film.

The significance of the boundary to the institution film is usually evident, either narratively or visually, in its opening scenes. One of the key shots of the prison narrative is a sense of overwhelming separation from the outside world when the prisoner first crosses the threshold of the prison. This is apparent either through the sound of (usually large) gates closing or, typically, as in The Shawshank Redemption (1994, directed by Frank Darabont), the protagonist’s point of view as he looks upward at the dominating entrance portal. The organization of an institution is also emphasized, with the spectator usually made aware of its spaces through the protagonist’s point of view. In filmic institutions, these spaces are predisposed towards a specific narrative function, though, in most cases, they still cohere to a generically panoptic model.

The panoptic model has been a central apparatus of the institutional age and it directly informed Michel Foucault’s37 analysis of the real institution. Foucault considered the ways in which the institution regulated bodies through its physical construction, and therefore established a relationship between space and control. While institutions are spaces implicitly concerned with the enforced discipline of the body, Foucault38 suggests that the typical panoptic structure of the institution also encourages internalized disciplinary processes; because prisoners do not know exactly when they are being observed they adjust their actions anyway (much in the same way that speed cameras operate). In films, this panoptic model may vary to accommodate the narrative, in some cases overtly emphasizing the disciplinary gaze, or in others focusing on the isolating features of institutional space. Some films may neglect the panoptic arrangement altogether, and instead negotiate the many, commonly labyrinthine, spaces of the institution as a way of propelling the narrative (and characters) forward.

In certain films, this mode of surveillance may be overlaid with genre dependent inflections such as the Gothic architecture of the prison and asylum in The Shawshank Redemption and Girl, Interrupted (1999). In futuristic films, we may see it replaced by digital surveillance, evident in the prisons of Fortress (1993, directed by S. Gordon) and Minority Report (2002, directed by Steven Spielberg). However, the fundamental concept of regulation through monitoring still persists.

In considering Foucault’s analysis of institutions in combination with a psychoanalytic approach to interpreting film, a number of tensions arise. Fundamentally, these two approaches are opposed. Not only do they constitute essentially different modes of analysis, but they are also polemical in content and nature, with one concerned with uniformity and the other with aberration. Kristeva’s theory of abjection considers both gender and race, and Freud focuses on sexuality and gender, while Foucault’s work on institutions appears impartial to all these aspects. Moreover, Foucault centres on the collective body and the environment of the institution, while Kristeva and Freud focus on the individual in relation to the maternal or parental world. For Foucault, generalized surveillance, physical coordination and knowledge govern the institutional body, while Kristeva’s maternal world is concerned with mapping the abject, corporeal body.

These two approaches are further dissonant in that Foucault is a critic of Freudianism and though Foucault’s concerns with ordering and discipline are similar to those of Freud and Kristeva, his ideas are essentially anti-psychoanalytic. For Foucault, Freudianism is rooted in a repression of sexuality, with perversion resulting from repression. In contrast, Foucault considers power to be a productive phenomenon, creating efficient, ordered subjects. The bringing together of two apparently irreconcilable approaches thus has various implications.

In this book I aim to correlate these two divergent approaches in relation to certain filmic contexts, since, though order and conformity may underpin real institutions, this is not the case in their filmic counterparts. Fictional film is more interested in aberration and, indeed, such aberration commonly underlies conventional narrative patterns. Where these approaches converge is in the control exerted through surveillance, knowledge and space. These aspects of control, in line with Foucault’s reasoning behind real institutions, aim to reduce aberration and encourage uniformity. However, in institution film narratives, excessive or even sadistic control generates narrative disorder. Such disorder generally arises in the reclamation of space, subjectivity and, often, liberation from the institution. Frequently, these involve the struggles of the individual against the institution. Narrative films therefore tend to be concerned with individuals, witnessed through devices that enable the spectator to identify with the protagonist, as in the use of close-up and point-of-view shots and voiceover. This is not to say that some films disregard the collective body, but that, in general, a focus on one or more key characters characterizes mainstream narrative film. Further, studies of the examples used in this book show that gender and race are significant in relation to the institution film and both are implicated in abjection. Finally, while institution narratives show evidence of a surveillant gaze closely associated with the maintenance of order, this often entails sexual desire. This desire is sometimes homoerotic in nature and usually coupled with sadistic impulses. Such a gaze therefore relates more to Freudian than Foucauldian perspectives. Even where fictional institutions appear to conform to a Foucauldian model, they seem inherently susceptible to disarray and breakdown.

Ultimately, therefore, it is possible to consider Foucault’s view of power as a way of ordering disorder. While his approach is not overtly repressive, it has parallels with Freudian psychoanalysis in that it entails an element of control. A repeated narrative in Foucault’s work is of a vital, chaotic, exciting world that is constantly under restraint. He makes frequent reference to the other as deviant, strange and occupying spaces (heterotopias) that are separate from the ‘normal’ world.39 Therefore, while Freud and Foucault may appear incompatible, there is common ground in the way they link control to the pathologicalization of difference. In a sense, Foucault is obsessed with the abject and uses space and hygiene as an attempt to distinguish between normal and other. In short, Foucault rejects the Freudian model of repression but still maintains a concern with systems of order as a mode of ‘containing’ the inherently chaotic.

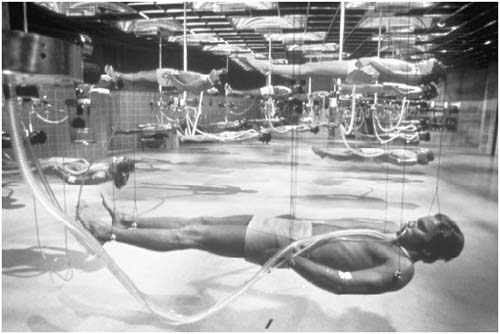

Despite acknowledging parallels between Foucault and Freud, in this book I conclude that, while the films discussed here emphasize Foucault’s ideas on power, in fictional institutions disorder rather than order prevails. A useful example of this is the uniform display of apparently healthy bodies at the Jefferson Institute in Coma (1978) (discussed later in this book, see Figure 1). This scene demonstrates the convergence of the ideas of Foucault and Kristeva, since the highly controlled and uniformly arranged bodies are subjectively ‘dead’ and exist at the border between life and death.

In summary, the ‘institution films’ discussed in this book initially appear to conform to Foucault’s model of discipline, but ultimately they demonstrate that constrictions of space, intrusive surveillance and knowledge of the individual fail as control mechanisms. The resultant reclamation of space relates to abjection in several ways. Space may be abject in that it involves either a return to a symbolically uterine state, or loss of subjectivity. Alternatively, the institution may function as a controlling maternal body, an aspect that may dictate the expression of the mise-en-scène. Further, the space itself may have links with death or decay or with premeditated cruelty. Thus, while Foucault is commonly associated with institutions, this work reappraises his ideas in relation to fictional institutions and shows that repression of autonomy arising from excessive control leads to the production of abject space.

In this book I thus analyse film texts about institutions using Kristeva’s theory of abjection. I explore a range of settings, from total institutions40 such as the prison, to everyday institutions such as the school and family, looking at how they give meaning and order space. The films analysed here include Bubba Ho-tep (2002), Carrie (1976), Coma (1978), Full Metal Jacket (1987), Girl, Interrupted (1999), The Last Castle (2001), Lock Up (1989), Remember the Titans (2000) and The Shawshank Redemption (1994). The choice of films rests on their setting being wholly or predominantly in institutions and on the latter being central to narrative progression. There are several other criteria for the selection of examples to be included in this analysis. First, to avoid discrepancies in visual representation arising through differences in culture and censorship, I create focus through nationality rather than conduct a generalized survey of institutions in film. Second, I also restrict the period of the films’ production to avoid similar variance associated with cultural shifts, production codes and restraints over time. Cinematographic conventions and technological developments that change with time may also affect modes of representation.

Since abjection is a consistent feature of the ‘institution genre’, I could have included earlier institution films, well-known examples being The Great Escape (1963), The Birdman from Alcatraz (1962), The Snake Pit (1948) and Papillon (1973). However, for reasons of consistency as stated above, and because censorship laws now allow for more explicit representation of abjection, I have limited this variable.

I therefore refer to American films from the 1970s to the present to focus on a national context and limited period of production. Establishing these limits allows one to examine a wide variety of films in relation to significant variables such as type of institution, gender and aspect of abjection. The most important element in the choice of films related to genre and type of institution. The films here represent a series of different institutional spaces and extend across various genres, ranging from horror, science fiction, melodrama and action through to the prison film. Crucially, they illustrate diverse aspects of abjection. Further, these films include a range of texts about masculinity and femininity in which abjection is generally associated with the institution as a feminized, maternal space from which a man has to escape or, on occasion, a masculinized, patriarchal space that oppresses women.

This book is divided into three sections. The training institution is examined first, and includes the films Carrie, Full Metal Jacket and Remember the Titans, which address either the marginalization of the feminine body, the emasculated body or the racial body. In the second section I analyse The Shawshank Redemption, Lock Up and The Last Castle, which are all penal institutions. These represent three different kinds of prison and modes of discipline – rehabilitation in The Shawshank Redemption, brutality in Lock Up, and a dependence on intrusive surveillance in The Last Castle. In the third and final section I examine the care institution and consider the boundary as a source of abjection. Here, Coma is concerned with the border between life and death, Girl, Interrupted centres on the border between madness and sanity and Bubba Ho-tep examines the diseased male reproductive body.

In the conclusion I suggest that the concept of abjection in the institution film addresses many of those aspects that Kristeva discusses in Powers of Horror while also asserting that Kristeva’s theory has some limitations. In addition, I acknowledge the potentially positive aspects of the abject; a point that emerges from this study is the political message apparent in most of the films. Certainly, several of the films examined comment adversely on aspects of the individual institution. This implicates a politicized dimension in the way that institutional spaces are represented. Finally, I conclude that in scenarios where repression exists, the abject always threatens to emerge and therefore suggests the inevitability of abject space in institutional settings. In effect, this book is intended to demonstrate and explain the representation of such abject spaces within fictional institutions.