VII.

LEIBNIZ AND PASCAL.230

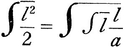

IN the History of Mathematics it is generally stated that the higher analysis took its rise in the method of indivisibles of Cavalieri (1635).231 This assertion, at least as far as the invention232 of the algorithm of the higher analysis is concerned, is erroneous. In what follows it will be shown, by argument founded on the work of the French mathematicians of the seventeenth century and on the manuscripts of Leibniz, that Leibniz was led to his invention of the algorithm of the higher analysis by a study of the writings of Pascal, more than by anything else.233

With regard to the manuscripts of Leibniz, the first letters of the correspondence between Leibniz and Tschirnhaus are weighty; they contain the further discussion of their joint labor during the time that they lived together in Paris (September, 1675, to November, 1676) ;234 it is well known that it was during this time that Leibniz invented the algorithm of the higher analysis. Among these letters, one from Leibniz, not hitherto published, which closes the first part of the correspondence between Leibniz and Tschirnhaus, contains a very detailed statement of the studies of Leibniz during his sojourn in Paris; it is beyond dispute of the utmost importance, since it was written only four years afterward and recalls particulars in a most vivid manner.235

Next, we have to consider the works of the French mathematicians about the middle of the seventeenth century, especially those of Pascal. We know from the facts of Pascal’s life that his father, when he moved to Paris in 1631, joined a circle of mathematicians and physicists,236 of which the history of science has preserved the names of Mersenne, Roberval, Gassendi, Desargues, de Carcavi, Beaugrand, des Billettes, and others. These were in communication , chiefly through Mersenne, with the mathematicians who did not live in Paris, Descartes, Fermat, and de Sluse ; so that about the middle of the seventeenth century all that was best (die Höhe der) in the science of mathematics was concentrated in Paris.237 In this circle Pascal moved, hardly yet out of his boyhood, and excited by his eminent talent astonishment and admiration. As an outstanding characteristic of the works of the mathematicians named above there stood forth the endeavor to abandon the method of Cavalieri as lacking every feature of scientific rigor, and to treat the science according to the methods of the Greek mathematicians.238 Perhaps the ideas of Kepler, in his Supplementum Stereometriae Archimedeae, 239 were of influence, when Roberval and Pascal introduced into geometry the ideas of infinity and the infinitely small.240

As for those works of Pascal, which belong to this subject, we must mention in particular the solution of the problems, produced by him in 1658 under the assumed name of Dettonville, on the cycloid. By this, and by the method that he employed, he surpassed all the mathematicians contemporary with him, and he earned for himself the fame of being the greatest geometer of his day.

The investigation of the properties of the cycloid had occupied the attention of the most famous mathematicians of the seventeenth century. It is reported that, earlier than anybody else and indeed before 1599, Galileo had had his attention called to this curve in consequence of his construction of arches for a bridge; he endeavored to find its area in a mechanical way, by weighing a plate of lead of uniform thickness having the shape of a plane bounded by a cycloid; and he found that it was very nearly three times as great as the area of the generating circle. This result he was unable to confirm theoretically. In 1615, Mersenne had his attention called to the cycloid as generated by a rolling wheel; he spent a great deal of time in investigating the nature of the curve, but without success; so that, in 1643, he corresponded with Roberval concerning the difficulties that he had encountered with respect to the curve. Roberval proved, by the help of the method of Cavalieri as improved by himself, that the area of the cycloid is exactly three times that of the generating circle; furthermore, in 1644, he determined the content of the solids formed by the rotation of the cycloid about its base, about its axis, and about the diameter of the generating circle; also he found the centroid of the area of the cycloid. In consequence of a bodily infirmity that robbed him of his rest at night, Pascal, in order to obtain some distraction from his pain, once more took up the investigation of the cycloid after an interval of fourteen years, in the year 1658. His design was to find the area of any chosen segment of the cycloid, the centroid of such a segment, the volumes of the solids described by such a segment by a rotation round either the ordinate or the abscissa, either by a complete, or a half, or a quarter revolution.241 Inasmuch as the solutions of the problems hitherto investigated had not been done by any general method, but rather by special arti-ficial ways of procedure, the question was that of specially creating a treatment that was applicable in general. Pascal reverted to the method of Archimedes, for determining the quadrature of the parabola by means of the equilibrium of the lever; he generalized the method,242 by supposing, instead of geometrical figures, unequal weights not merely at the extremities of the lever (which he follows Archimedes in terming balance) but also at several different distances from the fulcrum; of these, by means of the Arithmetical Triangle which he had invented,243 he determined the sum and the center of gravity. On the advice of his friends, Pascal, in June, 1658, under the alias of Detton-vile, 244 determined to propose to mathematicians for solution the problems that he had solved. October 1, 1658, was settled as the last day for sending in solutions. Particular cases of the proposed problems were solved by Huygens, de Sluse, and Wren, before the appointed day; but this was not sufficient to meet the requirements of Pascal. At the request of de Carcavi, Pascal made known the above-mentioned method for solving such propositions in a long letter, at the beginning of October, 1658,245 and added thereto three further propositions with respect to the cycloid. In this letter are combined five essays, which prepare the way for the solution of the problems of Pascal.

- i. Traitté des Trilignes et leurs Onglets.246

In this essay, the determination of the content and the centroid of a “triligne” and its “double onglet” is reduced to the sum of the ordinates of the axis or the base in a triligne; also Pascal showed that the determination of the content and the center of gravity of the curved surface of the double onglet could be expressed as the sum of the sines of the axis.247

The next essay,

- ii. Propriétés des sommes simples, triangulaires et pyra-midales,

is an appendix to the foregoing. By triangular sum, Pascal meant the sum of a number of magnitudes, each one multiplied in succession by the corresponding number in the natural scale. In the same way, a pyramidal sum denoted the sum of a number of magnitudes, each one in succession multiplied by the corresponding triangular number. 248

Then comes,

- iii. Traitté des sinus du quart de Cercle.

In this, Pascal begins by proving the theorem: “The sum of the sines of any arc of a quadrant of a circle is equal to the product of the part of the base, intercepted between the extremities of the outside sines, multiplied by the radius of the circle.” By the help of this theorem, he investigated the sum of the sines of a quadrant of a circle, their squares, their cubes, fourth and higher powers,249 the sum of the rectangles of each sine of the base into its distance from the axis, the triangular and pyramidal sums of the sines of the base, and so on.

The next essay,

- iv. Traitté des sinus et des arcs de Cercle,

contains the determination of the sum of all the arcs of a circle measured from the vertex of a quadrant to any ordinate of the axis, the sum of their squares, or their cubes, the corresponding triangular and pyramidal sums, the simple and triangular sums of the sectors, the sum of the solids formed from every sector of a quadrant and the distance of its center of gravity from the base, and so on.

- v. Petit Traitté des solides circulaires.

In this is investigated the position of the center of gravity of such bodies as are formed by the rotation of half a band of a circle about the axis or base, the sum of the fourth powers of the ordinates of the axis, of their cubes, the position of the center of gravity of the semisolid of revo-tution arising from a rotation about the axis, and so on.

These five essays conclude with:

Un Traitté general de la Roulette, contenant la Solution de tous les Problems touchant la Roulette qu’il avoit proposez publiquement au mois de Juin 1658.

All these works of Pascal are strictly geometrical in treatment, after the manner of the geometry of the ancients; there is not to be found in them a trace of the method of dealing with geometrical problems introduced by Descartes.250

It is well known that Leibniz through his acquaintance with Huygens, who lived in Paris from 1666 to 1681, was encouraged to study higher mathematics. More especially, it was Huygens who advised him to read the writings of Pascal. Upon several occasions later, has Leibniz declared, in conformity with this, that he was led to the higher analysis by the study of the writings of Pascal, and thus made his discoveries; first, in the hitherto unpublished letter to Tschirnhaus, of the year 1679, the part of it that relates to our subject being given later; also in a letter to the Marquis de l’Hospital, in the year 1694; further, in a postscript to a letter to Jacob Bernoulli, in the year 1703; and lastly, in the essay, Historia et Origo calculi differentialis, written in the last years of his life.

Up to the present time, among the manuscripts of Leibniz there has been found one of great length, that bears the title: Ex Dettonvillaeno ( ? ) seu Pascalii Geometricis excerpta: cum additamentis. It is not dated; but as it contains work that is in the closest connection with the writings of Pascal to de Carcavi, hence it must be assigned very approximately to the time of his intercourse with Huygens (1673). This cannot be given in its entirety; only the commencement of it follows under the heading III. One special remark has Leibniz made on the five essays which follow Pascal’s letter to de Carcavi;, he states that the method of Pascal for determining the surface of the sphere,251 according to which the surface of a solid formed by the rotation round an axis can be reduced to a plane figure proportional to it, was what induced him to make out a general theorem applicable to all plane figures bounded by a curved line.

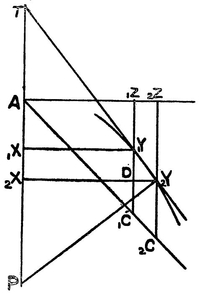

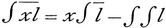

The coordinates of 1Y and 2Y, two points on the curve, are 1Y1Z, 1Y1X and 2Y2Z, 2Y2X ; 2YT is the tangent at 2Y, which is supposed to meet the curve again in 1Y, and the normal 2YP is drawn. On account of the similarity of the triangles 1YD2Yand 2Y2XP, we have

2XP.1YD = 2Y2X.2YD;

i. e., the subnormal 2XP applied, at right angles to the axis AX, to the element of the axis 1X2X(=1YD), is equal to the ordinate 2Y2X, applied to the element 2YD.252 “But,” Leibniz continues, “straight lines which increase from nothing, each multiplied by its corresponding element, form a triangle. For, let AZ be always equal to ZC, and you get the right-angled triangle AZC, which is half the square on AZ, and thus the figure produced by applying the subnormals in order at right angles to the axis is always equal to half the square on the ordinate. Hence, being given a figure to be squared, that figure is sought whose subnormals are equal to the ordinates of the given figure, and the second figure is the quadratrix of the given figure. Thus from this very simple idea, we have the reduction of surfaces produced by rotation to plane quadratures, and also of the rectification of curves ;253 and at the same time, we can reduce these quadratures to problems of inverse tangents.” Thus it came about that Leibniz obtained from this a general method for the quadrature of curves.

All this was arrived at by Leibniz in the first year, 1673/74, of his mathematical studies in regard to the higher analysis. Until this time he had adhered to the rigorous geometrical method, as he found it in the writings of Pascal, in his investigations; acting on the advice of Huygens, he now made himself acquainted with the method of Descartes as being more adapted to computation. The long essay of Leibniz with the title, Analysis Tetragonistica ex Centrobarycis, dated Oct. 25, 26, 29, and Nov. 1, 1675, shows clear connection254 with the above-mentioned method of Pascal; also it shows the improvement that Leibniz had made in consequence of his study of Cartesian geometry, Leibniz commences with Proposition 2 from Pascal’s first essay, Traitté des Trilignes et leurs Onglets, which he expresses as follows.

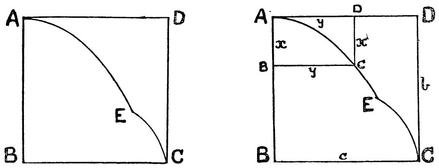

“Let any curve AEC be referred to a right angle BAD; let AB  DC

DC  a,255 and let the last x

a,255 and let the last x  b; also let BC

b; also let BC  AD

AD  y, and let the last y

y, and let the last y  c. Then it is plain that

c. Then it is plain that

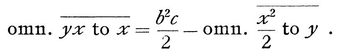

For, the moment of the space ABCEA about AD is made up of rectangles contained by BC (= y) and AB (= a) ;255 also the moment about AD of the space ADCEA, the complement of the former, is made up of the sum of the squares on DC halved (=x2/2) ; and if this moment is taken away from the whole moment of the rectangle ABCD about AD, i. e., from255 c into omn.x, or from255 b2c/a, there will remain the moment of the space ABCEA.

Hence the equation that I gave is obtained; and, by rearranging it, it follows that,

omn. yx to x + omn. X2 /2 to y = b2c/2.

In this way we obtain the quadrature of the two joined in one in every case; and this is the fundamental theorem in the center of gravity method.”

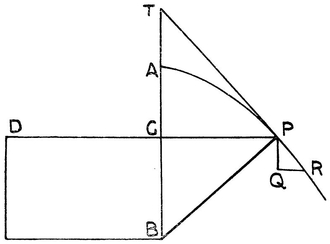

In the continuation, dated October 29, 1675, in connection with this theorem, Leibniz brings in the characteristic triangle, which has already been mentioned above.

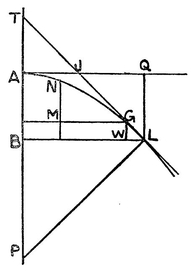

AGL is any curve, BL=y,

WL=l, BP=p, AB=x,

GW=a, y=omn.l;

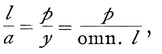

hence

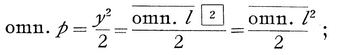

and therefore p =  .

.

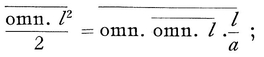

Now, by the theorem given above,256

hence

“that is,” adds Leibniz, “if all the l‘s are multiplied by their last, and all the other l’s again are multiplied by their last, and so on as often as it can be done, the sum of all these will be equal to half the sum of the squares, of which the sides are the sums of these, or all the /’s. This is a very fine theorem, and one that is not at all obvious. So is also the theorem,

omn. xl  x. omn. l— omn. omn. l,

x. omn. l— omn. omn. l,

where / is supposed to be a term of a progression, and x the number which expresses the position or ordinal that corresponds to the /, i. e., x is the ordinal number and / the ordered quantity.

N.B. In these calculations, a law for all things of the same kind may be observed; for, if ‘omn.’ is prefixed to a number or ratio, or to something indefinitely small,257 then a line is produced, also if to a line, then a surface, or if to a surface, then a solid; and so on to infinity for higher dimensions.

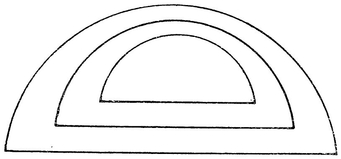

It will be useful258 to write ∫ for ‘omn.,’ so that

∫ l = omn. l, or the sum of all the /’s.

Thus,  , and

, and  .”

.”

This was the first time that the algorithm for the higher analysis was introduced. In what then follows, Leibniz obtains the first theorems of the integral calculus:

∫x = x2/2, ∫x2 = x3/3,

and adds, “All these theorems are true for series in which the differences of the terms bear to the terms themselves a ratio which is less than any assignable quantity.”

Further Leibniz remarks: “These things are new and noteworthy, since they lead to a new kind of calculus. Being given l, and its relation to x, required to find ∫l. Now this may be obtained by a reverse calculation; thus, if ∫ l = ya, suppose that l = ya/d, that is to say, as ∫ increases the dimensions, so d will diminish them; but ∫ stands for a sum, and d for a difference.259 From the given value of y, we can always find y/d or l, or the difference for the y’s.”

In the investigation that bears the title, Methodi tangentium inversae exempla, dated November II, 1675, Leibniz introduces instead of y/d the notation dy.

Such are the chief points in the story of the introduction of the algorithm of the higher analysis, as far as may be gathered from the extant manuscripts of Leibniz.260

In connection with the earlier essay, “Leibniz in London,” 261 I have shown that any influence whatever from external sources upon Leibniz with regard to the introduction of the algorithm of the higher analysis is excluded.

TRANSLATIONS OF THE MANUSCRIPTS

I.

From the letters of Leibniz to Tschirnhaus.

1679.

“You are astonished that Reginaldus262 should have been able to fall into error over the surface of an elliptic spheroid; but you do not seem to have considered sufficiently how different are the several methods of indivisibles. He certainly understands the Cavalierian method, but that is so circumscribed by narrow limitations that few things of any great importance can be obtained from it. There is no doubt that Cavalieri, Torricelli, Roberval, Fermat, and indeed, as far as I know, all the Italian mathematicians were quite unaware of the utility of tangents for the purpose of finding quadratures, or of that which I have been accustomed to call the infinitely small ”characteristic triangle” of the figure; indeed, at the present time also in France, I believe that Huygens is the only man that really understands these matters.263 Pascal himself could not sufficiently express his admiration for the artifice by which Huygens found the surface of the parabolic conoid. Sluse has given no example of these things, by which I am inclined to think that they are unknown to him also. This too is the reason why Huygens and Gregory demonstrated such theorems by roundabout methods, suppressing their analysis, in order not to divulge their method at once so easy and so fruitful.

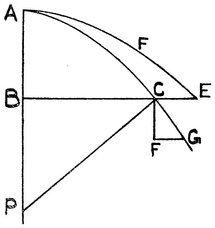

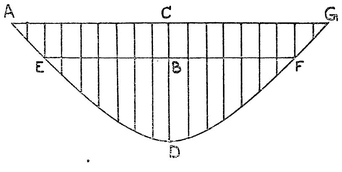

“The prime occasion from which arose my discovery of the method of the Characteristic Triangle, and other things of the same sort, happened at a time when I had studied geometry for not more than six months. Huygens, as soon as he had published his book on the pendulum, gave me a copy of it; and at that time I was quite ignorant of Cartesian algebra and also of the method of indivisibles, 264 indeed I did not know the correct definition of the center of gravity. For, when by chance I spoke of it to Huygens, I let him know that I thought that a straight line drawn through the center of gravity always cut a figure into two equal parts; since that clearly happened in the case of a square, or a circle, an ellipse, and other figures that have a center of magnitude, I imagined that it was the same for all other figures. Huygens laughed when he heard this, and told me that nothing was further from the truth. So I, excited by this stimulus, began to apply myself to the study of the more intricate geometry, although as a matter of fact I had not at that time really studied the Elements. But I found in practice that one could get on without a knowledge of the Elements, if only one was master of a few propositions. Huygens, who thought me a better geometer than I was, gave me to read265 the letters of Pascal, published under the name of Dettonville; and from these I gathered the method of indivisibles and centers of gravity, that is to say the well-known methods of Cavalieri and Guldinus. I immediately committed to paper certain things that occurred to me as I read Pascal, of which I now find that some are absurd, others please me very much even at the present time.266 Amongst other things, I tried to find a new sort of center. For, I thought that if, to any figure that was given, others that were similar and similarly placed were inscribed, then a “middle point” could be found,267 at which the figure evanesced, and that being given this point the quadrature could be obtained; later I perceived the difficulty that made this method ineffective. But to return to the subject, I will tell you how I came to find the method of the Characteristic Triangle. Incidentally Pascal gave a proof of the dimension of the spherical surface proved by Archimedes, that is the moment of a circular curve round the axis,268 and showed that the radius applied to the axis produced this moment. I, having examined the demonstration with care, observed that, with the aid of the infinitely small characteristic triangle, it was possible to prove the following general proposition for any curve:269

“Let AP be any curve and let BP be drawn perpendicular to its tangent AT, to meet the axis in B ; then, the ordinate PC being drawn, let the straight line CD be applied to the axis AC, perpendicular to it, and equal to BP. Then if a curve is drawn through all such points as D, we shall have a figure whose area will be the moment of the original curve about the axis, i. e., it will show how

to draw a circle equal in area to that of the surface of a curve rotated round the axis. Since in the circle the straight line BP is always of the same length wherever the point P is taken in the curve, hence the figure produced by the perpendiculars270 applied to the axis is a rectangle, and thus the surface of the sphere is very easily reduced to a plane area. Now, when from this method I had deduced a general method for the dimensions of such surfaces, I at once took it to Huygens; he was surprised and laughingly confessed that he had made use of precisely the same method for obtaining the surface of the parabolic conoid of revolution. For in that case the curve through every D is a parabola, and hence the figure is capable of quadrature. Since I wished to verify the accuracy of my result in the case of the parabola,271 I began to look for a method of expressing spaces and curves by reckoning, and then for the first time I really understood those matters of which Descartes wrote. For, previously, I used to calculate in my own way, using not letters but the names of lines. Then, for the first time, I read Descartes and Schooten carefully, acting on the advice of Huygens, who told me that the method of reckoning adopted by these authors was very convenient. Meanwhile having once opened the door provided by the characteristic triangle, I very easily discovered innumerable theorems with which at that time I filled innumerable sheets; but later I found that these had also been noted by Huraet, Gregory, and Barrow.272 Moreover all these things I came upon in the first year of my apprenticeship to geometry. But after that I struggled forward to far greater things, such as I believe that neither Gregory nor Barrow could ever have reached by their methods, far less Cavalieri or Fermat.273 About the same time, since I perceived that the finding of quadratures could be reduced to the finding of sums of series, and that the finding of tangents could be reduced to the finding of differences, I put together the fundamental principles of my new calculus,274 which I call the “differential or tetragonistic calculus,” by which I can set with a few little lines those things which could be obtained with great difficulty, if indeed at all, by the help of a mighty apparatus of lines. Moreover I considered in general that the finding of the sum of any series was nothing else but the discovering of some other series, the differences of the terms of which gave the given series, and this other series I used to call the summatrix.275 The occasion for considering infinite series arose from the work of Wallis and Mercator.276 When I joined their discoveries to mine, I found out new things with no trouble at all.

“At length, when I considered that problems of quadratures might not be of known degree, and yet might be reduced to equations, in which the exponents of the powers were unknowns, a new light dawned upon me and I began to understand that this was something beyond the ordinary analysis, and I called it transcendent, because it employed equations beyond all degrees; and I see that this method, almost alone of its kind, gives a method of determining whether particular problems of this kind are possible or not. Indeed I can easily prove in other ways, and also by the differential calculus more especially, the impossibility of general quadrature of the circle, or that no algebraical line can be given as its quadratrix. What I call algebraical lines are those that Descartes calls geometrical, and by quadratrices I mean all curves that, being described, will give the quadrature of any portion of a circle whatever. But the manner of finding the impossibility of any particular quadrature, for instance that of the whole circle, is known to me indeed in two ways, the one by the calculus of transcendent exponents, the other by a certain new kind of calculus, embracing all cases, which has not entered the mind of any one before even in his dreams.277

“Here you have the story of some of my meditations. . . .”

II.

From the correspondence between Leibniz and the Marquis de l’Hospital.

1694.

“I recognize that M. Barrow has advanced considerably, but I can assure you, Sir, that I have derived no assistance for my methods (pour mes methodes).278 At the start I only knew the indivisibles of Cavalieri,279 and the ‘ductions’ of Father Gregory St. Vincent, along with the “Synopsis of Geometry” of Father Fabri, and what could be derived from these authors and their like.280 When M. Huygens lent me the “Letters of Dettonville” (or Pascal), I examined by chance281 his demonstration of the measurement of the spherical surface, and in it I found an idea that the author had altogether missed; for I remarked that in general, by the same reasoning, the perpendiculars PC, when applied to the axis or set in the position BE, give a line FE, such that the area of the figure FABEF will furnish a development (explanation) of the surface formed by the rotation of AE about AB.

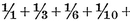

“Huygens was surprised when I told him of this theorem, and confessed to me that it was the very same as he had made use of for the surface of the parabolic conoid. Now, as that made me aware of the use of what I call the “characteristic triangle” CFG, formed from the elements of the coordinates and the curve, I thus found as it were in the twinkling of an eyelid nearly all the theorems that I afterward found in the works of Barrow and Gregory. Up to that time,282 I was not sufficiently versed in the calculus of Descartes, and as yet did not make use of equations to express the nature of curved lines; but, on the advice of Huygens, I set to work at it, and I was far from sorry that I did so: for it gave me the means almost immediately of finding my differential calculus.283 This was as follows. I had for some time previously taken a pleasure in finding the sums of series of numbers, and for this I had made use of the well-known theorem, that, in a series decreasing to infinity, the first term is equal to the sum of all the differences. From this I had obtained what I call the “harmonic triangle,” as opposed to the “arithmetical triangle” of Pascal; for M. Pascal had shown how one might obtain the sums of the figurate numbers, which arise when finding sums and sums of sums of the natural scale of arithmetical numbers. I on the other hand found that the fractions having figurate numbers for their denominators are the differences and the differences of the differences, etc., of the natural harmonic scale (that is, the fractions 1/1, 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, etc.), and that thus one could give the sums of the series of figurate fractions

etc.,

etc.,  etc.

etc.

Recognizing from this the great utility of differences and seeing that by the calculus of M. Descartes the ordinates of the curve could be expressed numerically, I saw that to find quadratures or the sums of the ordinates was the same thing as to find an ordinate (that of the quadratrix),284 of which the difference is proportional to the given ordinate. I also recognized almost immediately that to find tangents is nothing else but to find differences (differentier), and that to find quadratures is nothing else but to find sums, provided that one supposes that the differences are incomparably small. I saw also that of necessity the differential magnitudes could be freed from (se trouvent hors de) the fraction and the root-symbol (vinculum), and that thus tangents could be found without getting into difficulties over (se mettre en peine) irrationals and fractions.285 And there you have the story of the origin of my method. . . .”

[At this point Gerhardt quotes his article, Leibniz in London, and a long passage from the Historia, in corroboration of the foregoing letters. I have omitted them as I have already, in my notes, pointed out the points of resemblance, and the slight differences, between the several accounts that Leibniz gives.]

III.

Extracts from the geometry of Dettonville or Pascal; with additions.

Ca. 1673.

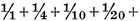

If A, B, C, D, are quantities, their triangular sum, starting with A, is 1A, 2B, 3C, 4D.

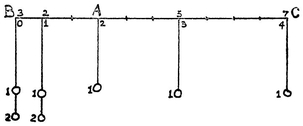

If BC is any straight line divided into any number of equal parts, and any weights, equal or unequal, are suspended at the points of division, and A is supposed to be their point of equilibrium, it is necessary that the triangular sum of the weights on the one arm AB should be equal to the triangular sum of the weights on the other arm AC, where the triangular sum on either side starts from the inner point or from the side A. The reason is that the weights give an effect that is compounded of the ratio of the weights and their distances from the center. But these distances, on account of the division of the straight line or beam of the balance into equal parts increase as 1, 2, 3, etc.

This is what Pascal says; to which I add the following remarks.

Even if the triangular sums on either side of the point are not the same, that is if the two arms are not in equilibrium, yet the moments will always be to one another as the triangular sums, for the moments are always equal to triangular sums.286 Hence the far more general rule: If any straight line is divided into any number of equal parts, and weighted with any number of weights suspended at the points of division, and if any point of division is taken to be A, then will the moments of the weights on the one arm BA be to the moments of the weights on the other arm CA as the tri-angular sums starting from that weight which is nearest to A on each side.287 Also when any figure, i. e., a line, a surface, or a solid, can be put in such a position that a certain line in it can be taken as parallel to the horizon, that straight line can be taken as a balance, and all the points or all the straight lines or all the planes (where the points in the line are assumed to be placed horizontally, or lying in planes of these points set perpendicular to the horizon), may be considered as weights; and thus, if the quantity or progression of these weights is known, and consequently their triangular sum, then the center of gravity of the figure is known; not indeed its position in the figure, but its position in the straight line that has been taken. The center of equilibrium in the figure itself is of this nature: namely, that a straight line passing through it will cut the figure into two parts, such that on each side the triangular sums of the points, straight lines, or horizontals of the solids are equal to one another. Hence the center of gravity of the whole figure being found, the centers of gravity of arms of this kind supposable without the figure may be obtained; for, let the figure be A, and let there be taken a line parallel to the horizon in which is the center of gravity B, and suppose that the center of gravity of it is placed above a horizontal style or suspended by a thread: then it is plain that the figure will be in equilibrium. But if it is in equilibrium, then the straight line CD, drawn through the center of gravity, will cut the figure in such a fashion that the triangular sums on each side are equal; and if moreover another straight line perpendicular to CD is supposed to be divided into an infinite number of parts by the infinite parallels to CD, the triangular sums of the infinite rectangles on each side will be equal to one another, for by hypothesis the rectangles can be supposed to be suspended as weights from EF as a balance at the points of division (from which it is clear that the suspended weights need not necessarily be understood to be perpendicular to the horizon, but they may be parallel to it). This being the case, the position of the figure may be changed from the horizontal to the perpendicular, and AG become the balance; in which case it is clear that the point of equilibrium will fall at C, since the triangular sums are by hypothesis equal on each side of it. Hence, given the center of gravity of any figure, and assuming a balance either without or within the figure, to which the figure is supposed to be rigidly attached, the point of equilibrium can be found in it, by merely drawing a perpendicular to it through the center of gravity; for this will cut the balance in the point of equilibrium. On the other hand, if the points of equilibrium of two balances for the same figure are given, the center of gravity for the figure can be found (whether it is within or without the given figure; for sometimes the center will fall within the given figure; and sometimes without, as in the case of annular figures, or curved lines, or other incomplete things) ; that is to say, at the point of intersection of two perpendiculars drawn from those two balances toward the same parts, in the same plane, if the figure is a plane figure, i. e., if the balances are in one and the same plane; but if the two balances are not in the same plane, there is need for three. This is to be investigated.288

But the following is a better way: Suppose that the figure is first affixed to one balance, and let the plane through the common perpendicular be the balance and the horizontal be drawn through the point of equilibrium to cut the figure; then let the figure be affixed to another balance, and once more let another plane be drawn to cut the figure; the intersection of these two planes will give a straight line which will contain the center of equilibrium. If now a third balance is taken in addition, or a third plane, the point of intersection of all the planes, or the point in which the third plane cuts the line already found, will be the center of equilibrium. But if the figures are planes, then two balances and two perpendiculars are sufficient; and also if they are curved lines that lie all in the same plane.

Now it is worth while noting several things in those cases in which the balance is not divided into equal parts; for it may happen that we may know in some way or other the sums of the weights and their progressions, but they are such that, when applied to the balance, they divide it into unequal parts; in that case the progression of the parts into which the balance is divided has to be investigated, as for instance if it is divided into parts that continually increase according to the squares or otherwise. Thus, if we wish to suppose that the weights are equal, while the balance is divided into parts that increase as 1, 2, 3, 4, etc., and yet that this case may come under the rule, we must proceed in this way. Suppose that that point of equilibrium is already found and that it is 2, say; then it is clear that, starting from the point 2 assumed to be the center, the arms should be numbered, and that the point 1 should be marked with the number 2, and the point P with the number 3, and on the other side the point 3 should be marked with the number 3, and the point 4 with the number 7. Now, supposing that the weights are multiplied by the numbers of their own points or arms, it is necessary that the product obtained should be equal;289 but if it is not, then another point must be sought (or something should be added to, or subtracted from, the weights; for instance, in this case, if the weights are 2, 3 should be supposed to be doubled, or in place of 1,1 we write 2,2 underneath, then there would be an equilibrium on each side, of 10). But to obviate the necessity of going through all the points, a formula should be sought; but if no known progression can be employed for the weights and the parts, a formula will be impossible; but when a known progression can be obtained, then a formula can be found as far as the nature of progression will allow. But the greater part of the difficulty will vanish in those cases in which the weights can be assumed to be equal. What is more, a very simple general rule has been found which is the reciprocal to that of Pascal, namely, that a point may be assumed such that the triangular sums of the numbers on each arm, always starting from the end and going toward the middle, are equal . . . . . . 290