For abbreviations used in this volume for these and other works, see the Bibliography given at the end.

This appeared in The Monist for October, 1916.

G. 1848, p. 29; see also G. math., III, pp. 71, 72, and Cantor, III, p. 40.

A fair-minded consideration, like everything emanating from the pen of De Morgan, is given of the matter in a recent edition of his Essays on the Life and Work of Newton. The tale is told with the charm characteristic of De Morgan, and the edition is rendered very valuable by the addition of notes, commentary, and a large number of references supplied by the editor, P. E. B. Jourdain (Open Court Publishing Co.). Special attention is directed to De Morgan’s summary of the unfairness of the case in Note 3 at the foot of pages 27-28.

See under 11 below: also cf. the original Latin as given in G. 1846, p. 4, “per amicum conscium.”

The account here given is substantially that given by Gerhardt in an article in Grunert’s Archiv der Mathematik und Physik, 1856; pp. 125-132.

This article is written in contradiction to the view taken by Weissenborn in his Principien der höheren Analysis, Halle, 1856. It is worthy of remark that the partisanship of Gerhardt makes him omit in this article all mention of the review which Leibniz wrote for the Acta Eruditorum on Newton’s work, De Quadratura Curvarum, which really drew upon him the renewal of the attack, by Keill. The passage which was objected to by the English mathematicians as being tantamount to a charge of plagiarism, in addition to the insult implied, according to their thinking, in making Newton the fourth proportional to Cavalieri, Fabri and Leibniz, is however given by Gerhardt in his preface to the Historia (G. 1846, p. vii).

Fatio’s correspondence with Huygens is to be found in Ch. Hugenii aliorumque seculi XVII virorum celebrium exercitationes mathematicae et philosophicae, ed. Uylenbroeck, 1833.

Bernoulli (Jakob), Opera, Vol. I, p. 431.

Ibid., p. 453.

Cantor, III, p. 221.

In the opening paragraph of the “postscript,” page 11.

The account which follows is taken from Williamson’s article, “Infinitesimal Calculus,” in the Times edition of the Encyc. Brit. The memoir referred to contains a passage, of which the following is a translation (G., 1846, p. v) :

“Perhaps the distinguished Leibniz may wish to know how I came to be acquainted with the calculus that I employ. I found out for myself its general principles and most of the rules in the year 1687, about April and the months following, and thereafter in other years; and at the time I thought that nobody besides myself employed that kind of calculus. Nor would I have known any the less of it, if Leibniz had not yet been born. And so let him be lauded by other disciples, for it is certain that I cannot do so. This will be all the more obvious, if ever the letters which have passed between the distinguished Huygens and myself come to be published. However, driven thereto by the very evidence of things, I am bound to acknowledge that Newton was the first, and by many years the first, inventor of this calculus; from whom, whether Leibniz, the second inventor, borrowed anything, I prefer that the decision should lie, not with me, but with others who have had sight of the paper of Newton, and other additions to this same manuscript. Nor does the silence of the more modest Newton, or the forward obtrusiveness of Leibniz....”

Truly another Roland in the field, and one in a vicious mood. What with other claimants to the method, such as Slusius, etc., at least as far as the differentiation of implicit functions of two variables is concerned, it would almost seem that the infinitesimal calculus was not an invention, but a gradual development of the fundamental principles of the ancient mathematicians.

See De Morgan’s Newton, p. 26 and pp. 148, 149, where the Scholium is translated. The original Latin of this Scholium to Lemma II of Book II of the Principia, the altered Scholium that appeared in the second and third editions, with a note remarking on the change, will be found on pp. 48, 49, in Book II of the “Jesuits’ Edition” of Newton (Editio Nova, edited by J. M. F. Wright, Glasgow, 1822; the third and best edition of the work of Le Seur and Jacquier).

Phil. Trans., 1708; see also Cantor, III, p. 299.

For a discussion, see Rosenberger, Isaac Newton und seine physikalischen Principien, Leipsic, 1895.

The manner of the opening of this postscript would seem to indicate that something had been mentioned with regard to the matter of his irritation about imputed obligations to Barrow in the body of the letter; this cannot be ascertained, for Gerhardt does not quote the letter in connection.

Leibniz can hardly with justice call Barrow his contemporary; Barrow anticipated him by half a dozen years at least. For Barrow had published his Lectiones Geometricae in 1670, while the very earliest date at which Leibniz could have obtained his results is the end of 1672; and there is reason to believe, as I have shown in my edition of the Lectiones, that Barrow was in possession of his method many years before publication, and had most probably communicated his secret to Newton in 1664.

It is to be noted that the sole topic of this postscript is geometry, of which Leibniz candidly states that he knew practically nothing in 1672.

Most probably the Institutiones arithmeticae of Johann Lantz, published at Munich in 1616; Cantor, III, p. 40.

Possibly the Geometria practica of Christopher Clavius, better known as an editor of Euclid; he was the professor at Rome under whom Gregory St. Vincent studied. There are repeated references to Clavius in Cantor, II and III, Index, q. v.

It is worth remarking that neither Lanzius nor Clavius is mentioned in the Historia.

It has been stated that, according to Descartes’s own words, the intricacies of his Géométrie were intentional; it certainly has the character of a challenge to his contemporaries. There is no preparation, such as marks a book of the present day on coordinate geometry; Descartes starts straightway on the solution of a problem given up as insoluble by the ancients. No wonder that young Leibniz found some difficulty with his first attempt to read it.

In 1635, Cavalieri published his Geometria indivisibilibus, and thus laid the foundation stone of the integral calculus. It would seem that Roberval was really the first inventor, or at least an independent inventor of the method; but he lost credit for it because he did not publish it, preferring to keep it to himself for his own use. Other examples of this habit are common among the mathematicians of the time.

The book referred to was published in 1654. It appeared as the second volume of a work whose first volume was a critique and refutation of the quadrature of the circle published by Gregory St. Vincent; this second volume was not the work of Leotaud, as the second part of the title showed: “necnon CURVILINEORUM CONTEMPLATIO, olim inita ab ARTUSIO DE LIONNE, Vapincensi Episc.” It therefore appears to have been an edited reprint of the work of De Lionne, the bishop of Gap (ancient name, Vapin-cum). Since part of this treatise is devoted to the “lunules of Hippocrates” (see Cantor, I, pp. 192-194), it may have had some influence with Leibniz in giving him the first idea for his evaluation of π.

Literally, “I was about to swim without corks.”

Leibniz here would appear to assert that he had considered some form of rectangular coordinate geometry, the association with the name of Descartes being fairly conclusive. Vieta’s In Artem Analyticam Isagoge explained how algebra could be applied to the solution of geometrical problems (Rouse Ball) ; for further information see Cantor.

This seems to have been an improvement on the adding machine of Pascal, adapting it to multiplication, division and extraction of roots. Pascal’s machine was produced in 1642, and Leibniz’s in 1671.

Huygens’s Horologium Oscillatorium was published in 1673; we are thus provided with an exact date for the occurrence of the conversation that set Leibniz on to read Pascal and St. Vincent. This was after his first visit to London, from which he returned in March, “having utilized his stay in London to purchase a copy of Barrow’s Lectiones, which Oldenburg had brought to his notice” (Zeuthen, Geschichte der Mathematik im XVI. und XVII. Jahrhundert; German edition by Mayer, p. 66). Leibniz himself mentions in a letter to Oldenburg, dated April 1673, that he has done so. Gerhardt (G. 1855, p. 48) states that he has seen, in the Royal Library of Hanover the copy of Barrow’s Lectiones Geometricae, so that it must have been the combined edition of the Optics and the Geometry, published in 1670, that Leibniz bought.

Thus, before he is advised to study Pascal by Huygens, he has already in his possession a copy of Barrow. It is idle that any one should suppose that Leibniz bought this book on the recommendation of a friend in order merely to possess it; Leibniz bought books, or borrowed them, for the sole purpose of study. Unless we are to look upon this account of his reading as the result of lack of memory extending back for thirty years, there is only one conclusion to come to, barring of course the obviously brutal one that Leibniz lied; and this conclusion is that at the first reading the only thing that Leibniz could follow in Barrow was the part that he marked Novi dudum (“Knew this before”), and this was the appendix to Lecture XI, which dealt with the Cyclometria of Huygens, as Barrow calls the book entitled De Circuli Magnitudine Inventa. The absence of any more such remarks is almost proof positive that Leibniz knew none of the rest before. Hence he must have read the Barrow before he had filled those “hundreds of sheets” that he speaks of later, with geometrical theorems that he has discovered; for at the end of the postscript we are considering he states that “in Barrow, when his Lectures appeared, I found the greater part of my theorems anticipated.” There is something very wrong somewhere; for this would appear to state that it was the second edition of Barrow, published in 1874, that Leibniz had bought; it is impossible, as the words of Leibniz stand, that they should refer to the 1670 edition, for it had been published before Leibniz arrived in Paris. It is however certain from Leibniz’s letter to Oldenburg that it could not be the 1674 edition, for the date of the letter is 1673. In this letter Leibniz merely makes a remark on the optical portion; but it could not have been the separate edition of the Optics, published in 1669, for Gerhardt states that the copy he has seen contains the Geometry with notes in the margin.

To those who have ever waded through the combined edition of Barrow’s Optics and Geometry, it may be that rather a startling suggestion will occur. It was sheer ill-luck that drove Leibniz, after studying the Optics (perhaps on the journey back from London, for we know that this was a habit of his), to get tired of the five preliminary geometrical lectures in all their dryness, and on reaching home, just to skim over the really important chapters, missing all the important points, and just the name of Huygens catching his eye. This is a new suggestion as far as I am aware; everybody seems to decide between one of two things, either that Leibniz never read the book until the date he himself gives, “Anno Domini 1675 as far as I remember,” or else that he purposely lied. I will return to this point later; meanwhile see Cantor, III, pp. 161-163, and consult the references given in the footnotes to these pages; the pros and cons of the conflict between probability and Leibniz’s word are there summarized.

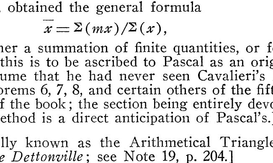

Pascal’s chief work on centers of gravity is in connection with the cycloid, and solids of revolution formed from it. His method was founded on the indivisibles of Cavalieri. His work was issued as a challenge to contemporaries under the assumed name of Amos Dettonville, and under the same name he published his own solutions, after solutions had been given by Huygens, Wallis, Wren and others.

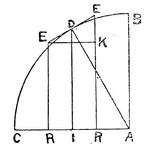

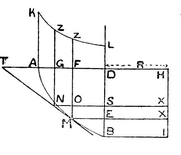

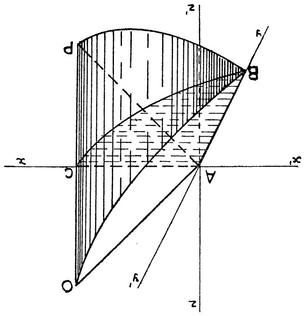

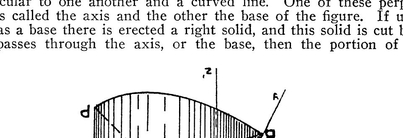

The method of ductus plani in planum, the leading or multiplication of a plane into a plane, employed by Gregory St. Vincent in the seventh book of his Opus Geometricum (1649) is practically on the same fundamental principle as the present method of finding the volume of a solid by integration. A simple explanation may be given by means of the figure of a quarter of a cone.

Let AOBC be the quarter of a circular cone (Fig. A), of which OA is the axis, and ABC the base, so that all sections, such as abc, are parallel to ABC and perpendicular to the plane AOC. Let ad be the height of a rectangle equal in area to the quadrant abc, so that ad is the average height of the variable plane abc ; then the volume of the figure is found by multiplying the height of the variable plane as it moves from O to the position ABC by the corresponding breadth of the plane OAC, i. e., by bc, and adding the results.

Fig. A.

As we shall see later, Leibniz does not fully appreciate the real meaning of the method; on the other hand Wallis uses the method with good effect in his Arithmetica Infinitorum, and states that he has come to it independently. In the above case he would have stated that the product in each case was proportional to the square on ac, drawn an ordinate ae at right angles to Oa, so that ae represented the product, and so formed the parabola OeEAaO, of which the area is known to him. This area is proportional to the volume of the cone.

Ungulae denote hoof-shaped solids, such as the frusta of cylinders or cones cut off by planes that are not parallel to one another.

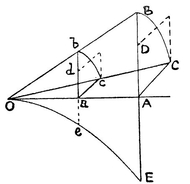

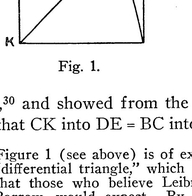

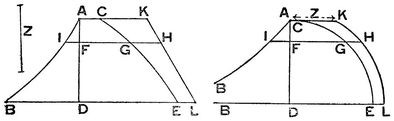

Figure 1 (see above) is of extreme interest. First of all it is not Barrow’s “differential triangle,” which is that of Fig. B below ; this of course is only what those who believe Leibniz’s statement that he received no help from Barrow, would expect. By the way, the figure given by Cantor as Barrow’s is not quite accurate. (Cantor, III, p. 135.)

Fig. B (BARROW).

Fig. C (PASCAL).

But neither is it the figure of Pascal, which is that of Fig. C. Of course, I am assuming that Gerhardt has given a correct copy of the figure given by Leibniz in his manuscript; although that which I have given of it, a faithful copy of Gerhardt’s, shows that his curve was not a circle. I also assume that Cantor is correct in the figure that he gives from Pascal; although Cantor says that the figure occurs in a tract on the sines of a quadrant, and not, as Leibniz states, in a problem on the measurement of the sphere. Indeed it seems to me that the figure is more likely to be connected with the area of the zone of a sphere and the proof that this is equal to the corresponding belt on the circumscribing cylinder than anything else. I am bound to assume these things, for I have not had the opportunity of seeing either of the figures in the original for myself. It is strange, in this connection, that Gerhardt in one place (G. 1848, p. 15) gives 1674 as the date of the publication of Barrow, and in another place (G. 1855, p. 45) seven years later, he makes it 1672, and neither of them is correct as the date of the copy that Leibniz could possibly have purchased, namely 1670. This is culpable negligence in the case of a date upon which an argument has to be founded, for one can hardly suspect Gerhardt of deliberate intent to confuse. Nevertheless, like De Morgan, I should have felt more happy if I could have given facsimiles of Barrow’s book, and Leibniz’s manuscript and figure.

Lastly, there is in Barrow (what neither Gerhardt, Cantor, nor any one else, with the possible exception of Weissenborn, seems to have noticed) chapter and verse for Leibniz’s “characteristic triangle.” Fig. D is the diagram that Barrow gives to illustrate the first theorem of Lecture XI. This is of course, as is usual with Barrow, a complicated diagram drawn to do duty for a whole set of allied theorems.

Fig. E.

In the proof of the first of these theorems occur these words:

“Then the triangle HLG is similar to the triangle PDH (for, on account of the infinite section, the small arc HG can be considered as a straight line).

Hence, HL : LG = PD : DH, or HL. DH = LG. PD,

i. e., HL. HO = DC. Dψ.

By similar reasoning, it may be shown that, since the triangle GMF is similar to the triangle PCG,....”

If now the lines in italics are compared with that part of the figure to which they refer, which has been abstracted in Fig. E, the likeness to Leibniz’s figure wants some explaining away, if we consider that Leibniz had the opportunity for seeing this diagram. Such evidence as that would be enough to hang a man, even in an English criminal court. (Further, see Note 46.)

To sum up, I am convinced that Leibniz was indebted to both of Barrow’s diagrams, and also to that of Pascal (for I will call attention to the fact that he uses all three, as I come to them) and I think that after the lapse of thirty years he really could not tell from whom he got his figure. In such a case it would be only natural, if he knew that it was from one of two sources and he was accused of plagiarizing from the one, that he should assert that it was from the other. Hence, by repetition, he would come to believe it. But even this does not explain his letter to d’Hospital, where he says that he has not obtained any assistance from his methods; unless again we remember that this letter is dated 1694, twenty years after the event.

Great importance, in my opinion hardly merited, is attached to the use by Leibniz of the phrase momento ex axe in this place, and in his manuscripts under the heading Analysis Tetragonistica ex Centrobarycis, dated October, 1675.

The Latin word momentum, a contraction of movimentum, has a primary meaning of movement or alteration, and a secondary meaning of a cause producing such movement. The present use of the term to denote the tendency of a force to produce rotation is an example of the use of the word to denote an effect ; from the second idea, we have first of all its interpretation as something just sufficient to cause the alteration in the swing of a balance (where the primary idea still obtains), hence something very small, and especially a very small element of time.

Thus we see that Leibniz uses the term in its primary sense, for he employs it in connection with a method ex Centrobarycis, and in its mechanical sense, and it is thus fairly justifiable to assume that he got the term from Huygens; in just this sense we now speak of the moment of inertia.

Newton’s use of the term is given in Lemma II of Book II of the Principia, in the following way.

“I shall here consider such quantities as undetermined or variable, as it were increasing or decreasing by a continual motion or flow (fluxus) ; and their instantaneous (momentanea) increments or decrements I shall denote (intelligo = understand) by the name “moments”; so that increments stand for moments that are added or positive (affirmativis), and decrements for those that are subtracted or negative.”

This has nothing whatever to do with what Leibniz means by a moment, and it seem ridiculous to bring forward the use of this word as evidence that Leibniz had seen Newton’s work, or even heard of it through Tschirnhaus, before the year 1675.

The fact that in another place, where I will refer to it again, he uses the phrase “instantaneous increment” is quite another matter.

The use of the word moment in this mechanical sense is here perfectly natural. See Cantor, III, p. 165 ; also Cantor, II, p. 569, where the idea is referred back at least to Benedetti (1530-1590) ; but the idea is fundamental in the theorems due to Pappus concerning the connection between the path of the center of gravity of an area and the surfaces and volumes of rings generated by the area, of which the proofs were given by Cavalieri. When, however, and by whom, the word moment was itself first used in this connection, I have been unable to find the slightest trace. (See p. 195.)

With due regard to the statement that Leibniz “had looked through Cavalieri” before he went to Paris, it is not remarkable that he did not notice very much at all in Cavalieri. Cavalieri’s Geometria Indivisibilibus is not a book to be “looked through.” It is a work for weeks of study. I cannot say whether the idea involved in Leibniz’s characteristic triangle is used by Cavalieri as such; but I do not see how else he could have given proofs (as stated by Williamson in his article on “Infinitesimal Calculus” in the Times edition of the Encyc. Brit.) of Pappus’s theorem for the area of a ring; and I should think that it is morally certain that Cavalieri is the source from which Wallis obtained his ideas for the rectification of the arc of the spiral. I had occasion to refer to a copy in the Cambridge University Library, and what I saw of it in the short time at my disposal determined me to make a translation of it, with a commentary, as soon as I had enough time at my disposal. “As one reads tales of romance” !

The moment is proportional to the area of the surface formed by the rotation of the curve C(C) about AP. Barrow does not at first use the method to find the areas of surfaces of revolution; he prefers to straighten out the curve C(C), and erect the ordinates BC, (B) (C) perpendicular to the curve thus straightened; i. e., he works with the product BC.C(C) as it stands. But, after giving the determination of the surface of a right circular cone as an example of the method, and as a means of combating the obiec-tions of Tacquet to the method of indivisibles, he goes on to say: “Evidently in the same manner we can investigate most easily the surfaces of spheres and portions of spheres (nay, provided all necessary things are given or known, any other surfaces that are produced in this way). But I propose to keep, to a great extent, to more general methods” (end of Lecture II). Thus we find that Barrow does not give any further examples of the determination of the areas of surfaces of revolution until Lecture XII. And why? Because he is not writing a work on mensuration, but a calculus. The reference to the method of indivisibles however shows that in Barrow’s opinion, if Cavalieri had not used his method for the determination of the area of the surface of a sphere, then he ought to have done so.

It is difficult to see also how Huygens could have performed his constructions unless he had used the method that Leibniz claims to have discovered.

It is strange that Roberval, as an independent discoverer of the method of indivisibles, did not perceive the method of the constructions of Huygens. Bullialdus is Ismael Bouilleau (Martin’s Biog. Philos.), or Boulliau (Poggen-dorff), author of works on conics, arithmetic of infinites, astronomy, etc. Cf. Seth Ward: In Ismaelis Bullialdi astron. philos. fundainento inquisitiones. Oxford, 1653.

This conversation probably took place late in 1673; see a note on the alteration of the date of a manuscript dated November 11, 1673, where the 3 was originally a 5 (see p. 93).

The method of Slusius (de Sluze, or Sluse) is as follows:

Suppose that the equation of the given curve is

x3−2x2y + bx2−b2x + by2− y3 = 0.

Slusius takes all the terms containing y, multiplies each by the corresponding index of y ; then similarly takes all the terms containing x, multiplies each by the corresponding index of x, and divides each term of the result by x; the quotient of the former by the last expression gives the value of the subtangent. This is practically the content of Newton’s method of analysis per aequationes, and Slusius sent an account of it to the Royal Society in January, 1673. It was printed in the Phil. Trans., as No. 90. This is given by Gerhardt (G. 1848. p. 15) as an example of the method of Slusius. It is rather peculiar that Gerhardt does not mention that this is the example given by Newton in the oft-quoted letter of December 10, 1672, and represents what Newton “guesses the method to be.” As it stands in G. 1848, it would appear to be a quotation from the work of Slusius himself. There is evidence that Leibniz had seen the explanation given in the Phil. Trans., or had been in communication with Slusius; this will be referred to later, but it may be said here that this fact makes Leibniz somewhat independent of any necessity of having seen Newton’s letter.

Some point is made of the question why, if Leibniz had seen the “differential triangle” of Barrow, he should have called it by a different name. If there were any point in it at all, it would go to prove that Barrow’s calculus was published by Barrow as a differential calculus. But there is no point, for Barrow never uses the term! It is a product of later growth, by whom first applied I know not. Leibniz, thus free to follow his logical plan of denominating everything, uses a term borrowed from his other work. He thus defines a character or characteristic. “Characteristics are certain things by means of which the mutual relations of other things can be expressed, the latter being dealt with more easily than are the former.” See Cantor, III, p. 33f.

Gregory’s Geometriae Pars Universalis was published at Padua in 1668. Leibniz had either this book, or the Barrow in which one of Gregory’s theorems is quoted, close at hand in his work. For he gives it as an example of the power of his calculus, referring to a diagram which is not drawn. This diagram I was unable to draw from the meager description of it given by Leibniz, until I looked up Barrow’s figure, in default of being able to obtain a copy of Gregory’s work; thereupon the figure was drawn immediately.

Here indeed it must be admitted that Leibniz is—suffering from a lapse of memory. As has been said before, Barrow’s lectures appeared in 1670 and were in the possession of Leibniz before ever he dreamed of his theorems. But what can one expect when admittedly this account (from which the Historia was in all probability written up) is purely from memory, aided by the few manuscripts that he had kept. Gerhardt does not say that he has found, nor does he publish, any manuscripts that could possibly give the order in which the text-books that Leibniz procured were read. Which of us, at the age of 57, could say in what order we had read books at the age of 27; or, if by then we had worked out a theory, could with accuracy describe the steps by which we climbed, or from a mass of muddle and inaccuracies, say to whom we were indebted for the first elementary ideas that we had improved beyond all recognition? I doubt whether any of us would recognize our own work under such circumstances.

Again Leibniz makes a bad mistake in affecting to despise the work of his rivals—for that is what the words, “these things were perfectly easy to the veriest beginner who had been trained to use them,” makes us believe. It is also bad taste, for, besides Barrow, Huygens also remained true to the method of geometry till his death. The sentence which follows savors of conceit; as a matter of fact it was left to others, such as the Bernoullis, to make the best use of the method of Leibniz. The great thing we have to thank Leibniz for is the notation; it is a mistake to call this the invention of a notation for the infinitesimal calculus. As we shall see, Leibniz invented this notation for finite differences, and only applied it to the case in which the differences were infinitely small. Barrow’s method, of a and e, also survives to the present day, under the disguise of h and k, in the method by which the elements of the calculus are taught in nine cases out of ten. For higher differential coefficients the suffix notation is preferable, and later on the operator D is the method par excellence.

Here Leibniz seems to be unable to keep from harking back to the charge made by Fatio, suggesting that by the publication of his letters by Wallis this charge has been proved to be absolutely groundless.

It is possible that this may mean “has received high commendation”; for elogiis may be the equivalent of eulogy, in which case celebratus est must be translated as “has been renowned.”

This is untrue. As has been said, the attack was first made publicly in 1699; at this time, although Huygens had indeed been dead for four years, Tschirnhaus was still alive, and Wallis was appealed to by Leibniz. It is strange that Leibniz did not also appeal to Tschirnhaus, through whom it is suggested by Weissenborn that Leibniz may have had information of Newton’s discoveries. Perhaps this is the reason why he did not do so, since Tschirnhaus might not have turned out to be a suitable witness for the defense. Leibniz must have had this attack by Fatio in his mind, for he could hardly have referred to Keill as a novus homo, while we know that he did not think much of Fatio as a mathematician. To say that there never existed any uncertainty as to the name of the true inventor until 1712 is therefore sheer nonsense; for if by that he means to dismiss with contempt the attack of Fatio, whom can he mean by the phrase novus homo ? The sneering allusion to “the hope of gaining notoriety by the discussion” can hardly allude to any one but Fatio. Finally if Fatio is dismissed as contemptible, the second attack by Keill was made in 1708. If it was early in the year, Tschirnhaus was even then alive, though Wallis was dead.

Gerhardt says in a note (G. 1846, p. 22) that his real name was probably Kramer; for what reason I am unable to gather. Cantor says distinctly that his name was Kaufmann, and this is the usually accepted name of the man who was one of the first members of the Royal Society and contributed to its Transactions. It seems to me that Gerhardt is guessing; the German word Kramer means a small shopkeeper, while Kaufmann means a merchant. To Mercator is due the logarithmic series obtained by dividing unity by (1 + x) and integrating the resulting series term by term; the connection with the logarithm of (1 + x) is through the area of the rectangular hyperbola y(1 + x) =0. See Reiff, Geschichte der unendlichen Reihen.

Newton obtained the general form of the binomial expansion after the method of Wallis, i. e., by interpolation. See Reiff.

We now see what was Leibniz’s point; the differential calculus was not the employment of an infinitesimal and a summation of such quantities; it was the use of the idea of these infinitesimals being differences, and the employment of the notation invented by himself, the rules that governed the notation, and the fact that differentiation was the inverse of a summation; and perhaps the greatest point of all was that the work had not to be referred to a diagram. This is on an inestimably higher plane than the mere differentiation of an algebraic expression whose terms are simple powers and roots of the independent variable.

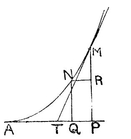

Why is Barrow omitted from this list? As I have suggested in the case of Barrow’s omission of all mention of Fermat, was Leibniz afraid to awake afresh the sleeping suggestion as to his indebtedness to Barrow? I have suggested that Leibniz read his Barrow on his journey back from London, and perhaps, tiring at having read the Optics first and then the preliminary five lectures, just glanced at the remainder and missed the main important theorems. I also make another suggestion, namely, that perhaps, or probably, in his then ignorance of geometry he did not understand Barrow. If this is the case it would have been gall and wormwood for Leibniz to have ever owned to it. Then let us suppose that in 1674 with a fairly competent knowledge of higher geometry he reads Barrow again, skipping the Optics of which he had already formed a good opinion, and the wearisome preliminary lectures of which he had already seen more than enough. He notes the theorems as those he has himself already obtained, and the few that are strange to him he translates into his own symbolism. I suggest that this is a feasible supposition, which would account for the marks that Gerhardt states are made in the margin. It would account for the words “in which latter I found the greater part of my theorems anticipated” (this occasion in future times ranking as the first time that he had really read Barrow, and lapse of memory at the end of thirty years making him forget the date of purchase, possibly confusing his two journeys to London) ; it would account for his using Barrow’s differential triangle instead of his own “characteristic triangle.” As Barrow tells his readers in his preface that “what these lectures bring forth, or to what they may lead you may easily learn from the beginnings of each,” let us suppose that Leibniz took his advice. What do we find? The first four theorems of Lecture VIII give the geometrical equivalent of the differentiation of a power of a dependent variable; the first five of Lecture IX lead to a proof that, expressed in the differential notation,

(ds/dx)2 = 1 + (dy/dx)2;

the appendix to this lecture contains the differential triangle, and five examples on the a and e method, fully worked out; the first theorem in Lecture XI has a diagram such that, when that part of it is dissected out (and Barrow’s diagrams want this in most cases) which applies to a particular paragraph in the proof of the theorem, this portion of the figure is a mirror image of the figure drawn by Leibniz when describing the characteristic triangle (turn back to note 30). I shall have occasion to refer to this diagram again. The appendix to this lecture opens with the reference to the work of Huygens; and the second theorem of Lecture XII is the strangest coincidence of all. This theorem in Barrow’s words is:

“Hence, if the curve AMB is rotated about the axis AD, the ratio of the surface produced to the space ADLK is that of the circumference of a circle to its diameter; whence, if the space ADLK is known, the said surface is known.”

The diagram given by Barrow is as usual very complicated, serving for a group of nine propositions. Fig. F is that part of the figure which refers to the theorem given above, dissected out from Barrow’s figure. Now remember that Leibniz always as far as possible kept his axis clear on the left-hand side of his diagram, while Barrow put his datum figure on the left of his axis, and his constructed figures on the right; then you have Leibniz’s diagram and the proof is by the similarity of the triangles MNR, PMF, where FZ = PM ; and the theorem itself is only another way of enunciating the theorem that Leibniz states he generalized from Pascal’s particular case! Lastly, the next theorem starts with the words: “Hence the surfaces of the sphere, both the spheroids and the conoids receive measurement.” What a coincidence!

Fig. F.

As this note is getting rather long, I have given the full proof of the first two theorems of Barrow’s Lecture XII as a supplement, at the end of this section.

The sixth theorem of this lecture is the theorem of Gregory which Leibniz also gives later; I will speak of this when I come to it. As also, when we discuss Leibniz’s proof of the rules for a product, etc., I will point out where they are to be found in Barrow ready to his hand.

Yet if all this were so, he could still say with perfect truth that, in the matter of the invention of the differential calculus (as he conceived the matter to consist, that is, the differential and integral notations and the method of analysis), he derived no assistance from Barrow. In fact, once he had absorbed his fundamental ideas, Barrow would be less of a help than a hindrance.

Apollonian geometry comprised the conic sections or curves of the second degree according to Cartesian geometry; curves of a higher degree and of a transcendent nature, like the spiral of Archimedes, were included under the term “mechanical.”

The great discovery of Descartes was not simply the application of geometry; that had been done in simple cases ages before. Descartes recognized the principle that every property of the curve was included in its equation, if only it could be brought out. Thus Leibniz’s greatest achievement was the recognition that the differential coefficients were also functions of the abscissa. The word function was applied to certain straight lines dependent on the curve, such as the abscissa itself, the ordinate, the chord, the tangent, the perpendicular, and a number of others (Cantor. III, preface, p. v). This definition is from a letter to Huygens in 1694. There is therefore a great advance made by 1714, the date of the Historia, since here it is at least strongly hinted that Leibniz has the algebraical idea of a function.

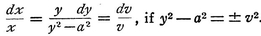

With regard to Newton, at least, this is untrue. Without a direct reference to the original manuscript of Newton it is quite impossible to state whether even Newton wrote 0 or 0 ; even then there may be a difficulty in deciding, for Gerhardt and Weissenborn have an argument over the matter, while Reiff prints it as 0. However this may be there is no doubt that Newton considered it as an infinitely small unit of time, only to be put equal to zero when it occurred as a factor of terms in an expression in which there also occurred terms that did not contain an infinitesimally small factor. This was bound to be the case, since Newton’s x and  were velocities. In short, expressing Newton’s notation in that of Leibniz, we have

were velocities. In short, expressing Newton’s notation in that of Leibniz, we have

0 or

0 or  0 = (dx/dt). dt

0 = (dx/dt). dt

and therefore  0 is an infinitesimal or a differential equal to Leibniz’s dx.

0 is an infinitesimal or a differential equal to Leibniz’s dx.

This is in a restricted sense true. No one seems to have felt the need of a second differentiation of an original function; those, who did, differentiated once, and then worked upon the function thus obtained a second time in the same manner as in the first case. Barrow indeed considered only curves of continuous curvature, and the tangents to these curves; but Newton has the notation  , etc. But the idea had been used by Slusius in his Meso-labum (1659), where a general method of determining points of inflection is made to depend on finding the maximum and minimum values of the subtangent. Lastly, it can hardly be said that Leibniz’s interpretation of ∫∫ ever attained to the dignity of a double integral in his hands.

, etc. But the idea had been used by Slusius in his Meso-labum (1659), where a general method of determining points of inflection is made to depend on finding the maximum and minimum values of the subtangent. Lastly, it can hardly be said that Leibniz’s interpretation of ∫∫ ever attained to the dignity of a double integral in his hands.

David Gregory is not the only sinner! Leibniz, using his calculus, makes a blunder over osculations, and will not stand being told about it; he simply repeats in answer that he is right (Rouse Ball’s Short History).

The names of the committee were not even published with their report. In fact the complete list was not made public until De Morgan investigated the matter in 1852 ! For their names see De Morgan’s Newton, p. 27.

What then made Leibniz change his mind?

It is established that this was Johann (John) Bernoulli; see Cantor, III, p. 313f ; Gerhardt gives a reference to Bossut’s Geschichte, Part II, p.219.

This seems to be an intentional misquotation from Bernoulli’s letter, which stated that Newton did not understand the meaning of higher differentiations. At least, that is what Cantor says was given in the pamphlet.

It is established that the pamphlet referred to was also an anonymous contribution by Leibniz himself! Is it strange that hard things are both thought and said of such a man?

Again this is Leibniz himself! Had he then no friends at all to speak for him and dare subscribe their signatures to the opinion? Unfortunately Tschirnhaus was dead at the time of the publication of the Commercium Epistolicum, but he could have spoken with overwhelming authority, as Leibniz’s co-worker in Paris, at any time between the date of Leibniz’s review of Newton’s De Quadratura in the Acta Eruditorum until his death in 1708, even if he had died before the publication of Keill’s attack in the Phil. Trans. of that year was made known to him. Does not this silence on the part of Tschirnhaus, the personal friend of Leibniz, rather tend to make Leibniz’s plea, that his opponents had had the shrewdness to wait till Tschirnhaus, among others, was dead, recoil on his own head, in that he has done the very same thing? Leibniz must have known the feeling that this review aroused in England, and, Huygens being dead, Tschirnhaus was his only reliable witness. Of course I am not arguing that Leibniz did found his calculus on that of Newton. I am fully convinced that they both were indebted to Barrow, Newton being so even more than Leibniz, and that they were perfectly independent of one another in the development of the analytical calculus. Newton. with his great knowledge of and inclination toward geometrical reasoning, backed with his personal intercourse with Barrow, could appreciate the finality of Barrow’s proofs of the differentiation of a product, quotient, power, root, logarithm and exponential, and the trigonometrical functions, in a way that Leibniz could not. But Newton never seems to have been accused of plagiarism from Barrow; even if he had been so accused, he probably had ready as an answer, that Barrow had given him permission to make any use he liked of the instruction that he obtained from him. Leibniz, when so accused. replied by asserting, through confusion of memory I suggest, that he got his first idea from the works of Pascal. Each developed the germ so obtained in his own peculiar way; Newton only so far as he required it for what he considered his main work, using a notation that was of greatest convenience to him, and finally falling back on geometry to provide himself with what appealed to him as rigorous proof; Leibniz, more fortunate in his philosophical training and his lifelong effort after symbolism, has ready to hand a notation, almost developed and perfected when applied to finite quantities, which he saw with the eye of genius could be employed as usefully for infinitesimals. De Morgan justly remarks that one dare not accuse either of these great men of deliberate untruth with regard to specific facts; but it must be admitted that neither of them can be considered as perfectly straightforward; and the political similitude, which Cantor speaks of, in which nothing is too bad to be said of an opponent, seems to have applied just as much to the mathematician of the day as to the politician.

This was given in more detail in the first draught of this essay (G. 1846, p. 26) : Hitherto, while still a pupil, he kept trying to reduce logic itself to the same state of certainty as arithmetic. He perceived that occasionally from the first figure there could be derived a second and even a third, without employing conversions (which themselves seemed to him to be in need of demonstration), but by the sole use of the principle of contradiction. Moreover, these very conversions could be proved by the help of the second and third figures, by employing theorems of identity; and then now that the conversion had been proved, it was possible to prove a fourth figure also by its help, and this latter was thus more indirect than the former figures. He marveled very much at the power of identical truths, for they were generally considered to be useless and nugatory. But later he considered that the whole of arithmetic and geometry arose from identical truths, and in general that all undemonstrable truths depending on reasoning were identical, and that these combined with definitions yield identical truths. He gave as an elegant example of this analysis a proof of the theorem, The whole is greater than its part.

It is fairly certain that Leibniz could not possibly at this time have perceived that in this theorem he has the germ of an integral. The path to the higher calculus lay through geometry. As soon as Leibniz attained to a sufficient knowledge of this subject he would recognize the area, under a curve between a fixed ordinate and a variable one as a set of magnitudes of the kind considered, the ordinates themselves being the differences of the set; he would see that there was no restriction on the number of steps by which the area attained its final size. Hence, in this theorem he has a proof to hand that integration as a determination of an area is the inverse of a difference. This does not mean the inverse of a differentiation, i. e., the determination of a rate, or the drawing of a tangent. As far as I can see, Leibniz was far behind Newton in this, since Newton’s fluxions were founded on the idea of a rate; also Leibniz apparently does not demonstrate the rigor of a method of infinitely narrow rectangles.

It is a pity that we are not told the date at which Leibniz read his Wallis; it is a greater pity that Gerhardt did not look for a Wallis in the Hanover Library and see whether it had the date of purchase on it (for I have handled lately several of the books of this time, and in nearly every case I found inserted on the title page the name of the purchaser and the date of purchase). I make this remark, because there arises a rather interesting point. Wallis, in his Arithmetica Infinitorum, takes as the first term of all his series the number 0, and in one case he mentions that the differences of the differences of the cubes is an arithmetical series. He also works out fully the sums of the figurate numbers (or as Leibniz calls them the combinatory numbers) ; the general formulas for these sums he calls their characteristics. He also remarks on the fact that any number (see table, p. 32) can be obtained by the addition of the one before it and the one above it (which is itself the sum of all the numbers in the preceding column above the one to the left of that which he wishes to obtain). Thus, in the fourth column 4 is the sum of 3 (to the left) and I (above), i. e., the sum of the two first numbers in column three; 10 is the sum of 6 (to the left) and 4 (above, which has been shown to be the sum of the first two numbers of column three), and therefore 10 is the sum of the first three numbers in column three. Now my point is, assuming it to have been impossible that Leibniz had read Wallis at the time that he was compiling his De Arte, we have here another example, free from all suspicion, of that series of instances of independent contemporary discoveries that seems to have dogged Leibniz’s career.

The name surdesolid to denote the fifth power is used by Oughtred, according to Wallis. By Cantor the invention of the term seems to be credited to Dechales, who says, “The fifth number from unity is called by some people the quadrato-cubus, but this is ill-done, since it is neither a square nor a cube and cannot thus be called the square of a cube nor the cube of a square: we shall call it supersolidus or surde solidus” (Cantor, III, p. 16). Wallis himself uses “sursolid.”

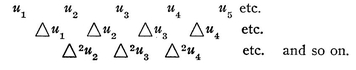

This theorem is one of the fundamental theorems in the theory of the summation of series by finite differences, namely,

which is usually called the direct fundamental theorem; for although Leibniz could not have expressed his results in this form since he did not know the sums of the figurate numbers as generalized formulas (or I suppose not, if he had not read Wallis), and apparently his is only a special case, yet it must be remembered that any term of the first series can be chosen as the first term. It is interesting to note that the second fundamental theorem, the inverse fundamental theorem, was given by Newton in the Principia, Book III, lemma V, as a preliminary to the discussion on comets at the end of this book. Here he states the result, without proof, as an interpolation formula; (it is frequently referred to as Newton’s Interpolation Formula) ; it may however be used as an extrapolation formula, in which case we have

um+n = um + nC1  Δum + nC2

Δum + nC2  Δ2 um + etc.

Δ2 um + etc.

In the two formulas as given here, the series are

What are we to understand by the inclusion of this series in this connection? Does Leibniz intend to claim this as his? I have always understood that this is due to Johann Bernoulli, who gave it in the Acta Eruditorum for 1694, in a slightly different form, and proved by direct differentiation; and that Brook Taylor obtained it as a particular case of a general theorem in and by finite differences. If Leibniz intended to claim it, he has clearly anticipated Taylor. It is quite possible that Leibniz had done so, even in his early days; and as soon as in 1675, or thereabouts, he had got his signs for differentiation and integration, it is possible that he returned to this result and expressed it in the new notation; for the theorem follows so perfectly naturally from the last expression given for a − ω. But it is hardly probable, for Leibniz would almost certainly have shown it to Huygens and mentioned it.

The other alternative is that here he is showing how easily Bernoulli’s series could have been found in a much more general form, i. e., as a theorem that is true (as he indeed states) for finite differences as well as for infinitesimals; the inclusion of this statement makes it very probable that this supposition is a correct one. This leads to a pertinent, or impertinent, question. Brook Taylor’s Methodus Incrementorum was published in 1715; the Historia was written some time between 1714 and 1716; Gerhardt states that there were two draughts of the latter, and that he is giving the second of these. In justice to Leibniz there should be made a fresh examination of the two draughts, for if this theorem is not given in the original draught it lays Leibniz open to further charge of plagiarism. I fully believe that the theorem will be found in the first draught as well and that my alternative suggestion is the correct one.

In any case, the tale of the Historia is confused by the interpolation of the symbolism invented later (as Leibniz is careful to point out). The question is whether this was not intentional. And this query is not impertinent, considering the manner in which Leibniz refrains from giving dates, or when we compare the essay in the Acta Eruditorum, in which he gives to the world the description of his method. Weissenborn considers that “this is not adapted to give an insight into his methods, and it certainly looks as if Leibniz wished deliberately to prevent this.” Cf. Newton’s “anagram” (sic), and the Geometry of Descartes, for parallels.

In reference to the employment of the calculus to diagrammatic geometry, as will be seen later, Leibniz says:

“But our young friend quickly observed that the differential calculus could be employed with figures in an even more wonderfully simple manner than it was with numbers, because with figures the differences were not comparable with the things which differed; and as often as they were connected together by addition or subtraction, being incomparable with one another, the less vanished in comparison with the greater.”

This makes what has just gone before date from the time previous to his reading of the work of Cavalieri. See note following.

This is about the first place in which it is possible to deduce an exact date, or one more or less exact. According to Leibniz’s words that immediately follow it may be deduced that it was somewhere about twelve months before the publication of the Hypothesis of Physics—if we allow for a slight interval between the dropping of the geometry and the consideration of the principles of physics and mechanics, and .a somewhat longer interval in which to get together the ideas and materials for his essay—that he had finished his “slight consideration” of Leotaud and Cavalieri. This would make the date 1670, and his age 24.

This essay founded the explanation of all natural phenomena on motion, which in turn was to be explained by the presence of an all-pervading ether; this ether constituted light.

The dedication of the Nova methodus in 1667 to the Elector of Mainz (ancient name Moguntiacum) procured for Leibniz his appointment in the service of the latter, first as an assistant in the revision of the statute-book, and later on the more personal service of maintaining the policy of the Elector, that of defending the integrity of the German Empire against the intrigues of France, Turkey and Russia, by his pen.

This probably refers to the time when his work on the statute-book was concluded, and Leibniz was preparing to look for employment elsewhere.

This is worthy of remark, seeing that Leibniz had attempted to explain gravity in the Hypothesis physica nova by means of his concept of an ether. The conversation with Huygens had results that will be seen later in a manuscript (see § 4, p.65) where Leibniz obtains quadratures “ex Centrobarycis.” It also probably had a great deal to do with Leibniz’s concept of a “moment.”

The use of the word veterno—which I have translated “lethargy” as being the nearest equivalent to the fundamental meaning, the sluggishness of old age—coupled with his remark that he was in no mind to enter fully into these more profound parts of mathematics, sheds a light upon the reason why he had so far done no geometry. Also the last words of the sentence give the stimulus that made him cast off this lethargy; namely, shame that he should appear to be ignorant of the matter. This would seem to be one of the great characteristics of Leibniz, and might account for much, when we come to consider the charges that are made against him.

We have here a parallel (or a precedent) for my suggestion that Leibniz was mentally confusing Barrow and Pascal as the source of his inspiration for the characteristic triangle. For here, without any doubt whatever, is a like confusion. What Pell told him was that his theorems on numbers occurred in a book by Mouton entitled De diametris apparentibus Solis et Lunae (published in 1670). Leibniz, to defend himself from a charge of plagiarism, made haste to borrow a copy from Oldenburg and found to his relief that not only had Mouton got his results by a different method, but that his own were more general. The words in italics are interesting.

Of course these words are not italicized by Gerhardt, from whom this account has been taken (G. 1848, p. 19) ; nor does he remark on Leibniz’s lapse of memory in this instance. Further there is no mention made of it in connection with the Historia, i. e., in G. 1846. Is it that Gerhardt, as counsel for the defense, is afraid of spoiling the credibility of his witness by proving that part of his evidence is unreliable? Or did he not become aware of the error till afterward? See Cantor, III, p. 76.

An instance is referred to on p. 85 of De Morgan’s Newton, showing the sort of thing that was done by the committee. This however is not connected with a letter to Oldenburg, but to Collins. It may be taken as a straw that shows the way the wind blew.

Observe that nothing has been said of the fact that Leibniz had purchased a copy of Barrow and took it back with him to Paris.

Cf. the remark in the postscript to Bernoulli’s letter, where Leibniz says that the work of Descartes, looked at at about the same time as Clavius, that is, while he was still a youth, “seemed to be more intricate.”

The libellus referred to would seem to be the work on the cycloid, written by Pascal in the form of letters, from one Amos Dettonville, to M. de Carcavi.

This theorem is given, and proved by the method of indivisibles, as Theorem I, of Lecture XII in Barrow’s Lectiones Geometricae; and Theorem II is simply a corollary, in which it is remarked:

“Hence the surfaces of the sphere, both the spheroids, and the conoids receive measurement....”

The proof of these two theorems is given at the end of this section as a supplement. See also Note 46, for its significance.

The whole context here affords suggestive corroboration in favor of the remarks made in Note 31 on the use of the word “moment,” though the connection with the determination of the center of gravity is here overshadowed by its connection with the surface formed by the rotation of an arc about an axis.

The figure given is exactly that given by Gerhardt, with the unimportant exception that, for convenience in printing, I have used U instead of Gerhardt’s θ, a V instead of his  (a Hebrew T), and a Q for his II. I take it, of course, that Gerhardt’s diagram is an exact transcript of Leibniz’s, and it is interesting to remark that Leibniz seems to be endeavoring to use T’s for all points on the tangent, and P’s for points on the normal, or perpendicular, as it is rendered in the Latin.

(a Hebrew T), and a Q for his II. I take it, of course, that Gerhardt’s diagram is an exact transcript of Leibniz’s, and it is interesting to remark that Leibniz seems to be endeavoring to use T’s for all points on the tangent, and P’s for points on the normal, or perpendicular, as it is rendered in the Latin.

This diagram should be compared with that in the “postscript” written nine or ten years before. Note the complicated diagram that is given here.

and the introduction of the secant that is ultimately the tangent, which does not appear in the first figure. From what follows, this is evidently done in order to introduce the further remarks on the similar triangles. It adds to the confusion when an effort is made to determine the dates at which the several parts were made out. For instance, the remark that finite triangles can be found similar to the characteristic triangle probably belongs approximately to the date of his reply to the assertions of Nieuwentijt, which will be referred to later.

The notation introduced in the lettering should be remarked. His early manuscripts follow the usual method of the time in denoting different positions of a variable line by the same letter, as in Wallis and Barrow, though even then he is more consistent than either of the latter. He soon perceives the inconvenience of this method, though as a means of generalizing theorems it has certain advantages. We therefore find the notation C, (C), ((C)), for three consecutive points on a curve, as occurs in a manuscript dated (or it should be) 1675. This notation he is still using in 1703; but in 1714, he employs a subscript prefix. This is all part and parcel with his usual desire to standardize and simplify notations.

This sentence conclusively proves that Leibniz’s use of the moment was for the purposes of quadrature of surfaces of rotation.

“From these results”—which I have suggested he got from Barrow—“our young friend wrote down a large collection of theorems.” These theorems Leibniz probably refers to when he says that he found them all to have been anticipated by Barrow, “when his Lectures appeared.” I suggest that the “results” were all that he got from Barrow on his first reading, and that the “collection of theorems” were found to have been given in Barrow when Leibniz referred to the book again, after his geometrical knowledge was improved so far that he could appreciate it.

The use of the first person is due to me. The original is impersonal, but is evidently intended by Leibniz to be taken as a remark of the writer, “the friend who knew all about it.” The distinction is marked better by the use of the first personal pronoun than in any other way.

Query, all except Leibniz, the Bernoullis, and one or two others.

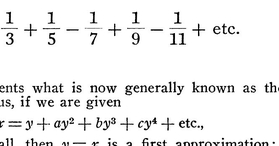

Tetragonism = quadrature; the arithmetical tetragonism is therefore Leibniz’s value for π as an infinite series, namely,

“The area of a circle, of which the square on the diameter is equal to unity, is given by the series

This is clearly original as far as Leibniz is concerned; but the consideration of a polar diagram is to be found in many places in Barrow. Barrow however forms the polar differential triangle, as at the present time, and does not use the rectangular coordinate differential triangle with a polar figure; nor does Wallis. We see therefore that Leibniz, as soon as ever he follows his own original line of thinking, immediately produces something good.

This is evidently a misprint; it is however curious that it is repeated in the second line of the next paragraph. Probably, therefore, it is a misreading due to Gerhardt, who mistakes AZ for the letters XZ, as they ought to be; and has either not verified them from the diagram, or has refrained from making any alteration.

The symbol  is here to be read as “and then along the arc to.”

is here to be read as “and then along the arc to.”

Probably refers to Leibniz’s work on curvature, osculating circles, and evolutes, as given in the Acta Eruditorum for 1686, 1692, 1694. It is to be noted that with Leibniz and his followers the term evolute has its present meaning, and as such was first considered by Huygens in connection with the cycloid and the pendulum. It signified something totally different in the work of Barrow, Wallis and Gregory. With them, if the feet of the ordinates of a curve are, as it were, all bunched together in a point, so as to become the radii vectores of another curve, without rupturing the curve more than to alter its curvature (the area being thus halved), then the first curve was called the evolute of the second and the second the involute of the first. See Barrow’s Lectiones Geometricae, Lecture XII, App. III, Prob. 9, and Wallis’s Arithmetica Infititorum, where it is shown that the evolute, in this sense, of a parabola is a spiral of Archimedes.

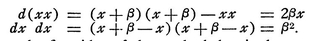

The colon is used as a sign of division, and the comma has the significance of a bracket for all that follows. It is curious to notice that Leibniz still adheres to the use of xx for x2, while he uses the index notation for all the higher powers, just as Barrow did; also, that the bracket is used under the sign for a square root, and that too in addition to the vinculum. For an easy geometrical proof of the relation x = 2z2/ (1 + z2), see Note 94.

See Cantor, III, pp. 78-81. Also note the introduction of what is now a standard substitution in integration for the purpose of rationalization.

This term represents what is now generally known as the method of inversion of series. Thus, if we are given

x = y + ay2 + by3 + cy4 + etc.,

where x and y are small, then y = x is a first approximation; hence since y = x − ay2 − by3 − cy4 − etc., we have as a second approximation

y = x − ax2;

substituting this in the term containing y2, and the first approximation, y = x, in the term containing y3, we have

y = x−a(x−ax2)2−bx3 = x−ax2+ (2a2−b)x3,

as a third approximation; and so on.

The relation x = 2z2/(1+z2) can be easily proved geometrically for the circle; hence, by using the orthogonal projection theorem, Leibniz’s result for the central conic can be immediately derived.

Thus suppose that, in the diagrams below, AC is taken to be unity, then AU = z and AX = x.

Then, in either figure, since the Δs BYX, CUA are similar,

AX : XB = AX. XB : XB2 = XY2: XB2 = AU2 : CA2;

hence, for the circle, we have

AX: AB = AU2 = : AC2 + AU2, or x = 2z2/(1+z2);

and similarly for the rectangular hyperbola

AX: AB = AU2: AC2−AU2, or x = 2z2/(1−z2).

Applying all the x’s to the tangent at A, we have (by division and integration of the right-hand side, term by term, in the same way as Mercator)

area AUMA = 2 (z3/3  z5/5 + z7/7

z5/5 + z7/7  etc.)

etc.)

Now, since the triangles UAC, YXB are similar, UA.XB=AC.XY; hence 2ΔAYC = 2UA.AC  UA.AX = 2UA.AC

UA.AX = 2UA.AC  AUMA

AUMA  2 seg. AYA, for Leibniz has shown that AXMA = 2 seg. AYA; hence it follows immediately that

2 seg. AYA, for Leibniz has shown that AXMA = 2 seg. AYA; hence it follows immediately that

sector ACYA = z  z3/3 + z5/5

z3/3 + z5/5  etc.

etc.

Fig. G.

Fig. H.

If now, keeping the vertical axis equal to unity, the transverse axis is made equal to a, Leibniz’s general theorem follows at once from the orthogonal projection relation.

Note that z is, from the nature of the diagrams, less than 1.

Wallis’s expression for π as an infinite product, given in the Arithmetica (or Brouncker’s derived expression in the form of an infinite continued fraction), or the argument used by Wallis in his work, could not possibly be taken as a proof that π could not be expressed in recognized numbers.

The letter that is missing would no doubt have been given, in the event of the Historia being published. According to Gerhardt it is to be found in Ch. Hugenii. . . .exercitationes, ed. Uylenbroeck, Vol. I, p. 6, under date Nov. 7, 1674.

Collins wrote to Gregory in Dec. 1670, telling him of Newton’s series for a sine, etc.; Gregory replied to Collins in Feb. 1671, giving him three series for the arc, tangent and secant; these were probably the outcome of his work on Vera Circuli (1667).

By Mercator; query, also an allusion to Brouncker’s article in the Phil. Trans., 1668.

Quite conclusive; no other argument seems required.

This date, April 12, 1675, is important; it marks the time when Leibniz first began to speak of geometry in his correspondence with Oldenburg, as he says below.

Newton obtained the series for arcsin x from the relation  :

:  = 1:

= 1:  , by expansion and integration, and then the series for the sine by the “extraction of roots.” See Note 93, and, for Newton’s own modification, Cantor, III, p. 73.

, by expansion and integration, and then the series for the sine by the “extraction of roots.” See Note 93, and, for Newton’s own modification, Cantor, III, p. 73.

It would appear from this that Leibniz could differentiate the trigonometrical functions. Professor Love, on the authority of Cantor, ascribes them to Cotes; but I have shown in an article in The Monist for April, 1916, that Barrow had explicitly differentiated the tangent and that his figures could be used for all the other ratios. Note the word “later” in the next sentence.

Probably only to test Leibniz’s knowledge.

Gerhardt states that in the first draft of the Historia, Leibniz had bordered the Harmonic Triangle, as given here, with a set of fractions, each equal to 1/1, so as to correspond more exactly with the Arithmetical Triangle.

The sign here used appears to be an invention of Leibniz to denote an identity, such as is denoted by ≡ at present.

This, and other formulas of the same kind, had been given by Wallis in connection with the formulas for the sums of the figurate numbers. Wallis called these latter sums the “characters” of the series.

This sentence, in that it breaks the sense from the preceding sentence to the one that follows, would appear to be an interpolated note.

There is an unimportant error here. The first value of x evidently should be 0, and not 1.

Why not? Newton’s dotted letters still form the best notation for a certain type of problem, those which involve equations of motion in which the independent variable is the time, such as central orbits. Probably Leibniz would class the suffix notation as a variation of his own, but the D-operator eclipses them all. For beginners, whether scholastic or historically such (like the mathematicians that Barrow, Leibniz and Newton were endeavoring to teach), the separate letter notation has most to recommend it on the score of ease of comprehension; we find it even now used in partial differential equations.

Leibniz does not give us an opportunity of seeing how he would have written the equivalent of dxdxdx; whether as dx3 or  or (dx)3.

or (dx)3.

Ductus and ungulae have already been explained in Notes 28, 29; cuneus denotes a wedge-shaped solid; cf. “cuneiform.”

This is peculiar. The demonstration that follows was beyond the powers of Leibniz in June, 1676 (see pp. 121, 122), probably so until Nov., 1676, when he was in Holland, and possibly later still. Hence the result would have been communicated to Huygens by letter, and there would be an answer from Huygens. I have been so far unable to find such a letter.

This only proves the proportionality, enabling Leibniz to convert the equation 2∫dy/y = 3∫dx/x into 2 log y = 3log x. It will hardly suffice as it stands to enable him to deal with such an equation as 2∫dy/y = 3∫x dx; and it is to be noted that Leibniz does not notice at all the constant of integration. Although Barrow has in effect differentiated (and therefore also has the inverse integral theorems corresponding thereto) both a logarithm and an exponential in Lecture XII, App. III, Prob. 3, 4, yet these problems are in such an ambiguous form that it may be doubted whether Barrow was himself quite clear on what he had obtained. Hence this clear statement of Leibniz must be considered as a great advance on Barrow.

Almost seems to read as a counter-charge against Newton of stealing Leibniz’s calculus. Note the tardy acknowledgement that Barrow has previously done all that Newton had given.

The whole effect that this Historia produces in my mind is that the entire thing is calculated to the same end as the Commercium Epistolicum. The pity of it is that Leibniz could have told such a straightforward tale, if events had been related in strict chronological order, without any interpolations of results that were derived, or notation that was perfected, later. A tale so told would have proved once and for all how baseless were the accusations of the Commercium, and largely explained his denial of any obligations to Barrow.

Let MP be perpendicular to the curve AB, and the lines KZL, αφδ such that FZ = MP, µφ = MF. Then the spaces αβδ, ADLK are equal.

For the triangles MRN, PFM are similar, MN : NR = PM : MF,

MN.MF = NR.PM;

that is, on substituting the equal quantities,

µν.µφ = FG. FZ, or rect. µθ = rect. FH.

But the space αβδ only differs in the slightest degree from an infinite number of rectangles such as µθ, and the space ADLK is equivalent to an equal number of rectangles such as FH. Hence the proposition follows.

Hence, if the curve AMB is rotated about the axis AD, the ratio of the surface produced to the space ADLK is that of the circumference of a circle to its diameter; whence if the space ADLK is known, the said surface is known.

Some time ago I assigned the reason why this was so.

Hence, the surfaces of the sphere, both the spheroids, and the conoids receive measurement. For if AD is the axis of the conic section, etc.

§§ 3-10 inclusive appeared in The Monist for April, 1917.

It is impossible to see, without a fuller knowledge of the context,whether this refers to “compensation of errors,” or whether Leibniz is alluding to the possibility of all the finite terms cancelling one another.

Leibniz comes back to this point later; see § 5.

This, without either proof or figure, is a hopeless muddle; and yet it is repeated word for word, without any addition or remark, in Gerhardt’s 1855 publication. Goodness knows what the use of it was supposed to be in this form! Unless Leibniz has omitted some length, which he has supposed to be unity, the dimensions are all wrong.

The sign  signifies multiplication.

signifies multiplication.

Observe that as yet nothing has been said about the area of surfaces of revolution or moments about the axis, although we should expect them to be mentioned in connection with the figure that is given; for the next manuscript shows that in October 1675, Leibniz has already done a considerable amount of work on moments.

Gerhardt has a footnote to the effect that, as nearly as possible he has retained the exact form of this and the manuscripts that immediately follow; except in the matter of this one sign I have adhered to the form given by Leibniz.

Weissenborn, Principien der höheren Analysis, Halle, 1856.

This a should be x.

Here, in the Latin, “ac m omn.x” should be “a c in omn.x.”

In view of this accurate bit of algebra, the faulty work in subsequent manuscripts seems very unaccountable.

This proves the fundamental theorem given lower down, with regard to a pair of parallel straight lines; and he now goes on to discuss the case of non-parallel straight lines.

The passage in Gerhardt reads:

Datis ergo duobus momentis figurae ex duabus rectis non parallelis, dabitur figurae momentis tribus axibus librationis, qui non sint omnes paralleli inter se, dabitur figurae area, et centrum gravitatis.

For this I suggest:

Datis ergo tribus momentis figurae ex tribus rectis non parallelis, aliter figurae momentis tribus axibus librationis, qui non sunt omnes paralleli inter se. . . .

The passage would then read:

Given three moments of a figure about three straight lines that are not parallel, in other words, the moments of the figure about three axes of libration, which are not all parallel to one another, then the area of the figure will be given and also the center of gravity.

If the alternative words are written down, one under the other, and not too carefully, I think the suggested corrections will appear to be reasonable.

Apparently, here Leibniz is referring back to the theorem at the beginning of the section.

I have given this equation, and those that immediately follow it, in facsimile, in order to bring out the necessity that drove Leibniz to simplify the notation.

We have here a very important bit of work. Arguing in the first instance from a single figure, Leibniz gives two general theorems in the form of moment theorems. The first is obvious on completing the rectangle in his diagram, and this is the one to which the given equation applies. In the other the whole, of which the two parts are the complements, is the moment of the completed rectangle; its equivalent is the equation

omn.xy = ult.x omn.y − omn. omn.y.

Now, although Leibniz does not give this equation, it is evident that he recognized the analogy between this and the one that is given; for he immediately accepts the relation as a general analytical theorem that he can use without any reference to any figure whatever, and proceeds to develop it further. This would therefore seem to be the point of departure that led to the Leibnizian calculus.

Having freed the matter from any reference to figures, he is able to take any value he pleases for the letters. He supposes that z = 1, and thus obtains the last pair of equations. He then considers x and w as the abscissa and ordinate of the rectangular hyperbola xw = a (constant) ; hence omn.a/x or omn. w is the area under the hyperbola between two given ordinates, and therefore a logarithm; and thus omn. omn.a/x is the sum of logarithms, as he states. See Note 60, p. 122.

There only seem to be two possible sources for this paragraph, (1) original work on the part of Leibniz, and (2) from Barrow. For we know that Neil’s method was that of Wallis, and the method of Van Huraet used an ordinate that was proportional to the quotient of the normal by the ordinate in the original curve.

Now Barrow, in Lect. XII, § 20, has the following: “Take as you may any right-angled trapezial area (of which you have sufficient knowledge), bounded by two parallel straight lines AK, DL, a straight line AD, and any line KL whatever; to this let another such area be so related that when any straight line FH is drawn parallel to DL, cutting the lines AD, CE, KL in the points F, G, H, and some determinate line Z is taken, the square on FH is equal to the squares on FG and Z. Moreover, let the curve AIB be such that, if the straight line GFI is produced to meet it, the rectangle contained by Z and FI is equal to the space AFGC; then the rectangle contained by Z and the curve AB is equal to the space ADLK. The method is just the same, even if the straight line AK is supposed to be infinite.”

This striking resemblance, backed by the fact that there seems to be no connection between this theorem and the rest of the paper, that Leibniz gives no attempt at a proof, (indeed I very much doubt whether I could have made out his meaning from the original unless I had recognized Barrow’s theorem) and that Leibniz gives 1675 as the date of his reading Barrow, almost forces one to conclude that this is a note on a theorem (together with an original deduction therefrom by himself) which Leibniz has come across in a book that is lying before him, and that that book is Barrow’s. Against it, we have the facts of the use of the word “quadratrix,” not in the sense that Barrow uses it, namely as a special curve connected with the circle; that the quadratrix is one of the special curves that Barrow considers in the five examples he gives of the Differential Triangle method; and that another example of this method is the differentiation of a trigonometrical function which seems to be unknown to Leibniz.

This is either a misprint, v instead of O, or else Leibniz is in error. For Slusius’s method there must be only two variables in the equation. In the Phil. Trans. for 1672 (No. 90), Sluse gives his method thus:

If y5 + by4 = 2qqν3 − yyν3 then the equation must be written y5 + by4 + yyν3 = 2qqν3 − yyν3; then multiply each term on the left-hand side by the number of y’s in the term, and substitute t in place of one y in each; similarly multiply each term on the left-hand side by the exponent of ν; the equation obtained will give the value of t.

The use of the letters v and y is to be noted in connection with Leibniz’s use of the same letters; it does not seem at all necessary that Leibniz should have seen Newton’s work, with this ready to the former’s hand, as a member of the Royal Society. I suggest that Sluse obtained his rule by the use of a and e, as given in Barrow. Can Barrow’s words usitatum a nobis (in the midst of a passage written in the first person singular) have meant that the method was common property to himself and several other mathematicians that were contemporary with him? This would explain a great deal.

There is evidently a slip here; l should be x.

This is an instance of the care which Leibniz takes; in the work above l has been the difference for y, and a the difference for x; he is now integrating an algebraical expression, and not considering a figure at all; hence l = a, and a is equal to unity, and therefore ∫l3 = l3x = a3x = x! Thus what is generally considered to be a muddle turns out to be quite correct. The muddle is not with Leibniz, it is with the transcriber. It is certain that these manuscripts want careful republishing from the originals; won’t some millionaire pay to have them reproduced photographically in an edition de luxe?