CHAPTER 6

1. Understand the Analytical Task

2. Read the Passage Using the “Three-Pass Approach”

3. Construct Your Thesis and Outline

The SAT Essay

What is the SAT Essay?

The SAT includes an optional 50-minute Essay assignment designed to assess your

proficiency in writing a cogent and clear analysis of a challenging rhetorical essay written for a broad audience.

Should you choose to accept the challenge, the SAT Essay will be the fifth and final section of your test.

The SAT Essay assignment asks you to read a 650–750 word rhetorical essay (such as a New York Times op-ed about the economic pros and cons of using biofuels) and to write a well-organized response that

• demonstrates an understanding of the essay’s central ideas and important details

• analyzes its use of evidence, such as facts or examples, to support its claims

• critiques its use of reasoning to develop ideas to connect claims and evidence

• examines how it uses stylistic or persuasive elements, such as word choice or appeals to emotion, to add power to the ideas expressed

How is it used?

Many colleges use the SAT Essay in admissions or placement decisions. Many also regard it as an important indicator of essential skills for success in college, specifically, your ability to demonstrate understanding of complex reading assignments, to analyze arguments, and to express your thoughts in writing.

Sound intimidating? It’s not.

If you have mastered the analytical reading skills discussed in Chapters 4 and 5, you already have a strong start on tackling the SAT Essay, since strong active reading of the source text is the first and most important step in the analytical writing task. There are four rules to success on the SAT Essay, and the 13 lessons in this chapter will give you the knowledge and practice you need to master all of them.

Understand the Analytical Task

Lesson 1: Use your 50 minutes wisely

The SAT Essay assesses your proficiency in reading, analysis, and writing. You are given 50 minutes to read an argumentative essay and write an analysis that demonstrates your comprehension of the essay’s primary and secondary ideas and your understanding of its use of evidence, language, reasoning, and rhetorical or literary elements to support those ideas. You must support your claims with evidence from the text and use critical reasoning to evaluate its rhetorical effectiveness.

So what should you do with those 50 minutes?

Reading: 15–20 minutes

Although 15–20 minutes may seem like a long time to devote to reading a 750-word essay, remember that you must do more than simply read the essay. You must comprehend the essay and analyze its stylistic and rhetorical elements. In other words, you must master the “Three-Pass Approach” that we will practice in lessons 4–6. This is a fairly advanced reading technique, and you will need to devote substantial time to practicing it. Even once you’ve mastered it, you will still need to set aside 15–20 minutes on the SAT Essay section to read and annotate the passage thoroughly.

Organizing: 10–15 minutes

Your next task is to gather the ideas from your analyses and use them to formulate a thesis and structure for a five- or six-paragraph essay. If you have performed your first task properly and have completed your “Three-Pass” analysis, creating an outline will be much easier. We will discuss these tasks in lessons 7 and 8.

Your thesis should summarize the thesis of the essay and its secondary ideas, describe the author’s main stylistic and rhetorical elements, and explain how these elements support (or detract from) the author’s argument.

Take your time with this process, too. Don’t start writing before you have articulated a thoughtful guiding question and outlined the essay as a whole.

Writing: 20–25 minutes

Next, of course, you have to write your easy. To get a high score, your essay must provide an eloquent introduction and conclusion, articulate a thesis summarizing the central claims and the main rhetorical and stylistic elements of the essay, be well organized, show a logical and cohesive progression of ideas, maintain a formal style and an objective tone, and show a strong command of language. But if you’ve followed these steps, which we will explore in more detail below, the essay will flow naturally and easily from your analysis and outline.

Lesson 2: Learn the format of the SAT Essay

SAT Essay passages are “op-ed” passages that present a point of view on a topic in the arts, sciences, politics, or culture. They address a broad audience, express nuanced views on complex subjects, and use evidence and reasoning to support their claims.

Below is a sample essay and prompt (from the diagnostic test in Chapter 2). Read it carefully to familiarize yourself with the instructions and format.

You have 50 minutes to read the passage and write an essay in response to the prompt provided below.

DIRECTIONS

As you read the passage below, consider how Steven Pinker uses

• evidence, such as facts or examples, to support his claims

• reasoning to develop ideas and connect claims and evidence

• stylistic or persuasive elements, such as word choice or appeals to emotion, to add power to the ideas expressed

Adapted from Steven Pinker, “Mind Over Mass Media.” ©2010 by The New York Times. Originally published June 10, 2010.

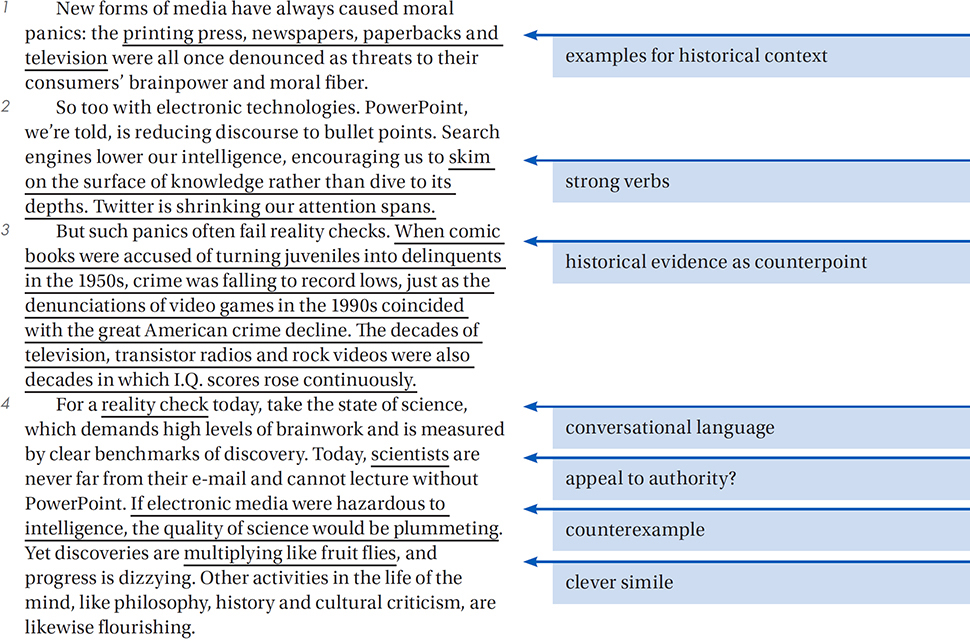

1 New forms of media have always caused moral panics: the printing press, newspapers, paperbacks and television were all once denounced as threats to their consumers’ brainpower and moral fiber.

2 So too with electronic technologies. PowerPoint, we’re told, is reducing discourse to bullet points. Search engines lower our intelligence, encouraging us to skim on the surface of knowledge rather than dive to its depths. Twitter is shrinking our attention spans.

3 But such panics often fail reality checks. When comic books were accused of turning juveniles into delinquents in the 1950s, crime was falling to record lows, just as the denunciations of video games in the 1990s coincided with the great American crime decline. The decades of television, transistor radios and rock videos were also decades in which I.Q. scores rose continuously.

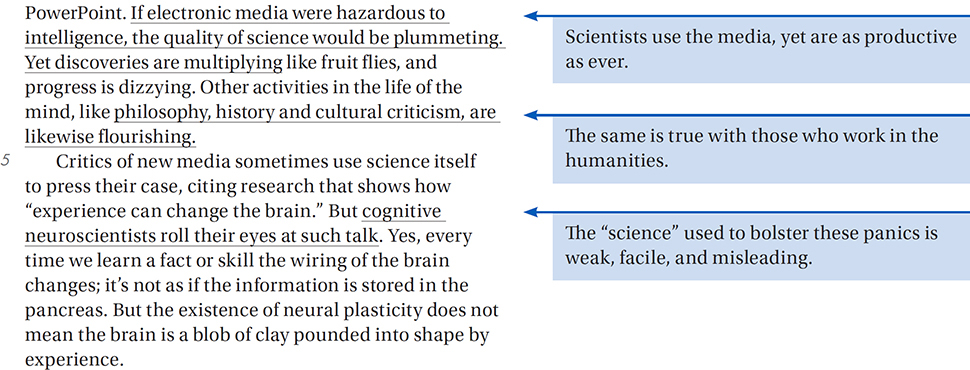

4 For a reality check today, take the state of science, which demands high levels of brainwork and is measured by clear benchmarks of discovery. Today, scientists are never far from their e-mail and cannot lecture without PowerPoint. If electronic media were hazardous to intelligence, the quality of science would be plummeting. Yet discoveries are multiplying like fruit flies, and progress is dizzying. Other activities in the life of the mind, like philosophy, history and cultural criticism, are likewise flourishing.

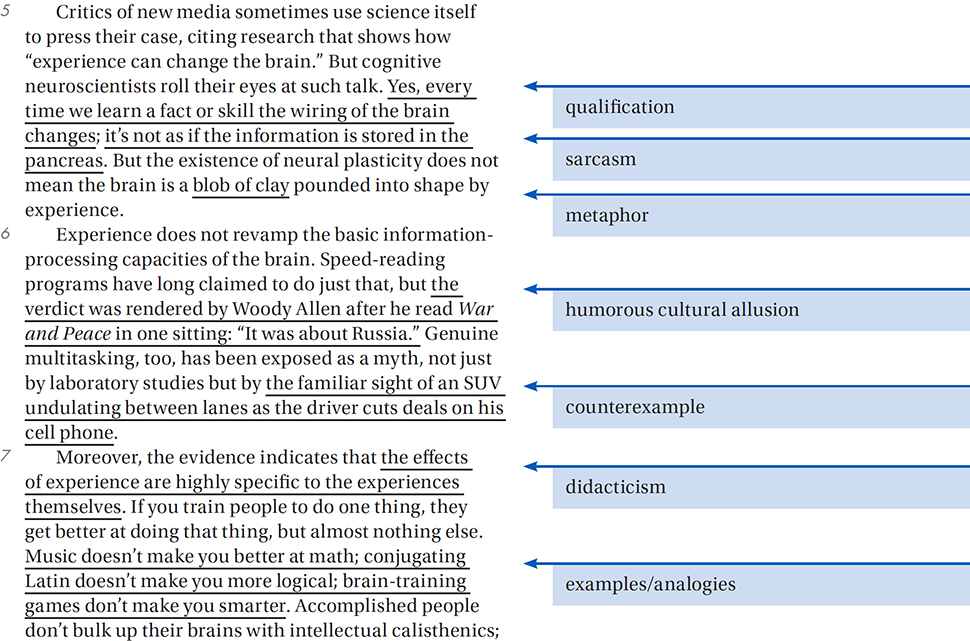

5 Critics of new media sometimes use science itself to press their case, citing research that shows how “experience can change the brain.” But cognitive neuroscientists roll their eyes at such talk. Yes, every time we learn a fact or skill the wiring of the brain changes; it’s not as if the information is stored in the pancreas. But the existence of neural plasticity does not mean the brain is a blob of clay pounded into shape by experience.

6 Experience does not revamp the basic information-processing capacities of the brain. Speed-reading programs have long claimed to do just that, but the verdict was rendered by Woody Allen after he read War and Peace in one sitting: “It was about Russia.” Genuine multitasking, too, has been exposed as a myth, not just by laboratory studies but by the familiar sight of an SUV undulating between lanes as the driver cuts deals on his cellphone.

7 Moreover, the evidence indicates that the effects of experience are highly specific to the experiences themselves. If you train people to do one thing, they get better at doing that thing, but almost nothing else. Music doesn’t make you better at math; conjugating Latin doesn’t make you more logical; brain-training games don’t make you smarter. Accomplished people don’t bulk up their brains with intellectual calisthenics; they immerse themselves in their fields. Novelists read lots of novels; scientists read lots of science.

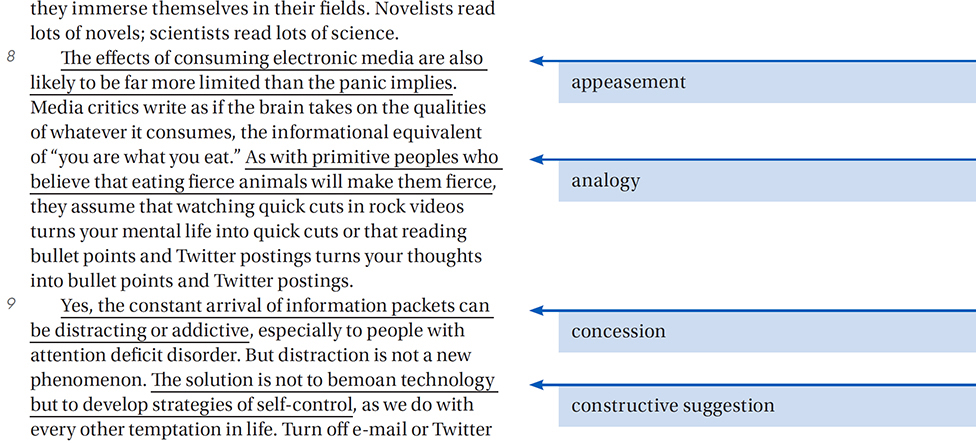

8 The effects of consuming electronic media are also likely to be far more limited than the panic implies. Media critics write as if the brain takes on the qualities of whatever it consumes, the informational equivalent of “you are what you eat.” As with primitive peoples who believe that eating fierce animals will make them fierce, they assume that watching quick cuts in rock videos turns your mental life into quick cuts or that reading bullet points and Twitter postings turns your thoughts into bullet points and Twitter postings.

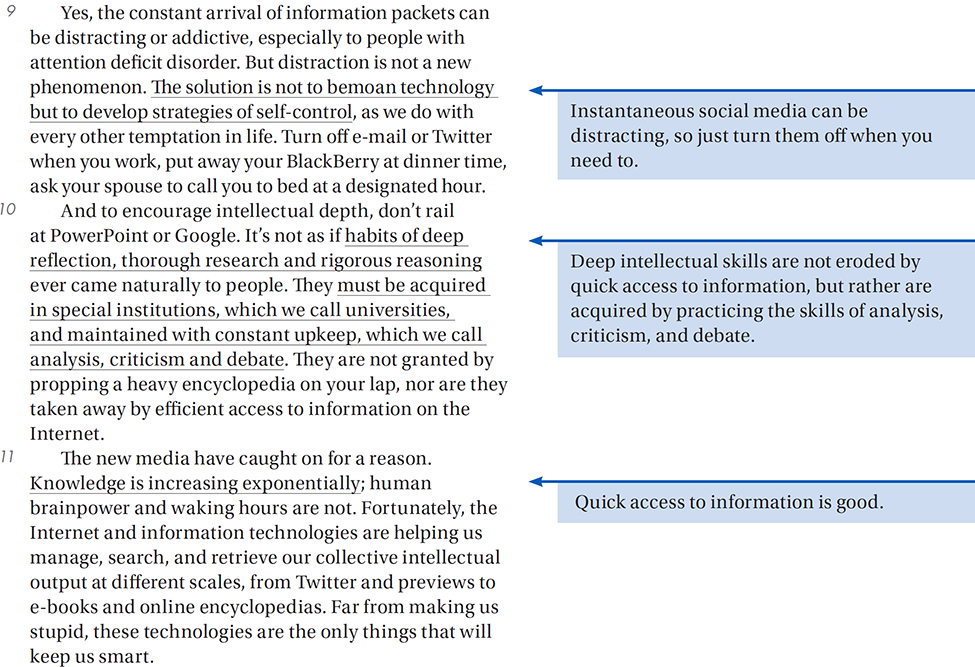

9 Yes, the constant arrival of information packets can be distracting or addictive, especially to people with attention deficit disorder. But distraction is not a new phenomenon. The solution is not to bemoan technology but to develop strategies of self-control, as we do with every other temptation in life. Turn off e-mail or Twitter when you work, put away your BlackBerry at dinner time, ask your spouse to call you to bed at a designated hour.

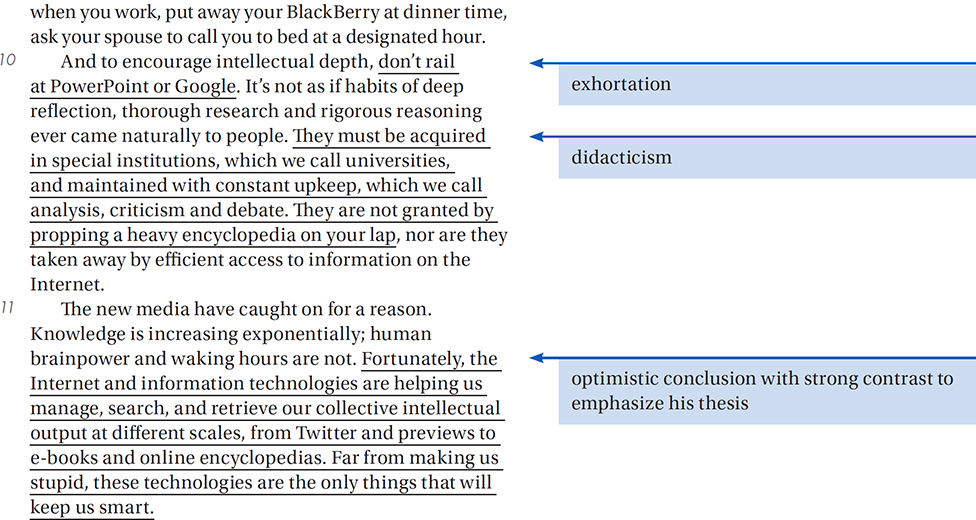

10 And to encourage intellectual depth, don’t rail at PowerPoint or Google. It’s not as if habits of deep reflection, thorough research and rigorous reasoning ever came naturally to people. They must be acquired in special institutions, which we call universities, and maintained with constant upkeep, which we call analysis, criticism and debate. They are not granted by propping a heavy encyclopedia on your lap, nor are they taken away by efficient access to information on the Internet.

11 The new media have caught on for a reason. Knowledge is increasing exponentially; human brainpower and waking hours are not. Fortunately, the Internet and information technologies are helping us manage, search, and retrieve our collective intellectual output at different scales, from Twitter and previews to e-books and online encyclopedias. Far from making us stupid, these technologies are the only things that will keep us smart.

Write an essay in which you explain how Steven Pinker builds an argument to persuade his audience that new media are not destroying our moral and intellectual abilities. In your essay, analyze how Pinker uses one or more of the features listed in the box above (or features of your own choice) to strengthen the logic and persuasiveness of his argument. Be sure that your analysis focuses on the most relevant features of the passage.

Your essay should NOT explain whether you agree with Pinker’s claims, but rather explain how Pinker builds an argument to persuade his audience.

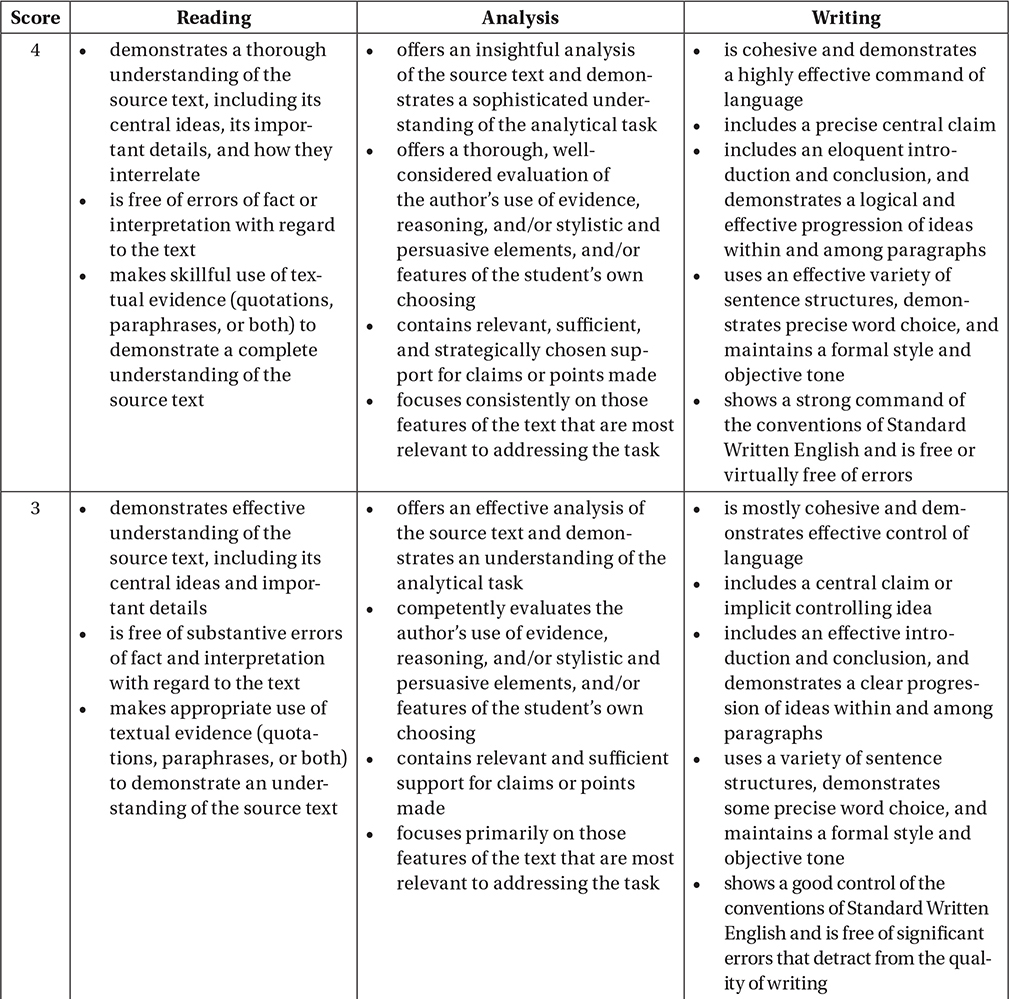

Lesson 3: Understand the scoring rubric

Your essay will be scored based on three criteria: reading, analysis, and writing. Two trained readers will give your essay a score of 1 to 4 on these three criteria, and your subscore for each criterion will be the sum of these two, that is, a score from 2 to 8. Here is the official rubric for all three criteria.

SAT Essay Scoring Rubric

Read the Passage Using the “Three-Pass Approach”

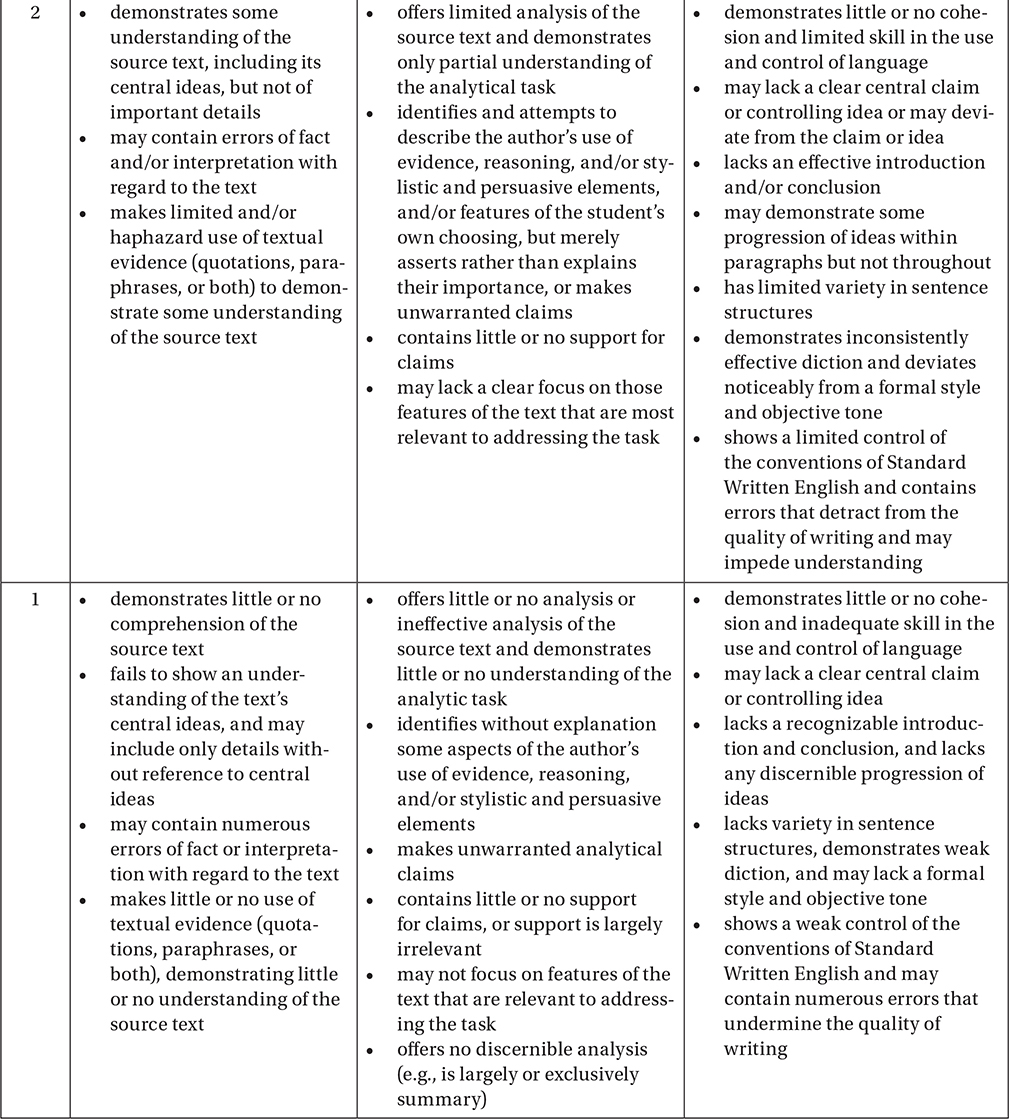

Lesson 4: First pass: Summarize

Use the first 15 to 20 minutes to read the passage thoroughly, using the “three-pass approach” described in these next three lessons. In the first pass, read and summarize the passage as we discussed in Chapter 4, asking, “What is the central thesis, who is the audience, and what is the general structure of the essay?” Underline key points and summarize the passage with annotations.

Let’s apply this strategy to the essay from the diagnostic test in Chapter 2. (If you haven’t already completed your diagnostic test essay, flip back to Chapter 2 and do it now!)

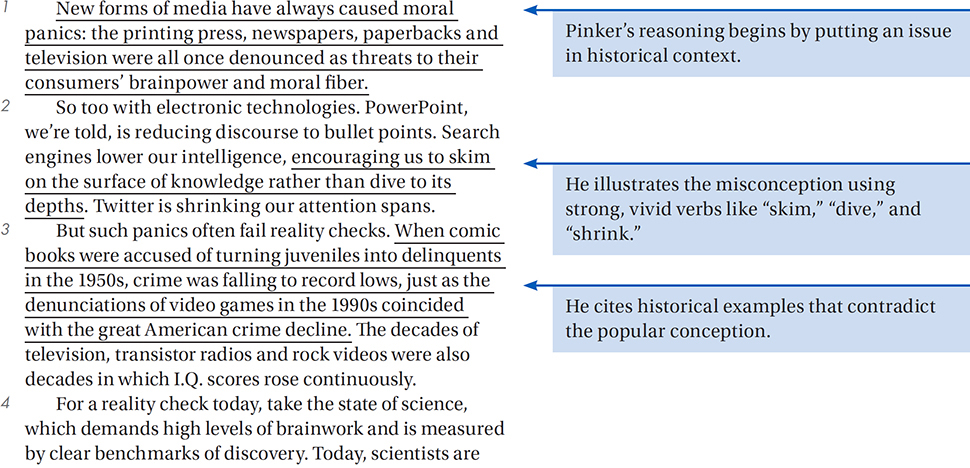

Adapted from Steven Pinker, “Mind Over Mass Media.” ©2010 by The New York Times. Originally published June 10, 2010.

First pass: Summarize

Lesson 5: Second pass: Analyze

Now read the passage again, focusing on the specific rhetorical and stylistic devices that the author uses to support his or her argument. In particular, note how the author uses evidence, reasoning, appeals to values and emotions, and literary elements to support his or her claims. Pay attention to the five categories or rhetorical elements: logos, pathos, ethos, mythos, and poetics.

Logos—how a writer uses reasoning and evidence to support claims.

• What kind of reasoning does the author use to support claims?

• Dialectical reasoning: Examining two sides of an issue objectively (the thesis and the antithesis) and arriving at a synthesis that resolves problems with each position.

• Deductive reasoning: Showing that the claim follows from first principles.

• Inductive reasoning: Showing that the claim follows a pattern of examples.

• What kind of evidence does the author use to support claims?

• Anecdotal evidence: Using personal stories to support a claim.

• Empirical evidence: Using studies, polls, or objective facts to support a claim.

• Historical evidence: Showing how the claim fits within a context of historical events.

• Does the author commit any of these common logical fallacies?

• Straw man fallacy: Misrepresenting an opposing viewpoint to make it easier to attack. (E.g., If you support background checks for gun purchases, then you want to take away my right to protect my family!)

• Overgeneralization fallacy: Applying an idea beyond the situations in which it is appropriate. (E.g. Cutting taxes helped the economy during the last recession, so it will help boost the economy now that corporate profits are at a record high!)

• Ad hominem fallacy: Attacking the person rather than the person’s argument. (E.g., You don’t have a Ph.D., so why should I believe you?)

• Consensus or authority fallacy: Suggesting that something is true simply because many people believe it, or because a famous or reputable person or institution claims that it is true. (E.g., If everyone believes it, it must be true; If Einstein said it, it must be true.)

• Correlation for causation fallacy: Suggesting that one thing causes another simply because the two are correlated. (E.g., Rich people get higher SAT scores, therefore the SAT only measures how rich you are.)

• Slippery slope fallacy: Suggesting that one cannot set a standard along a continuum. (E.g., If we lower the drinking age to 18, what will prevent us from lowering it to 3?)

Pathos—how a writer appeals to the reader’s emotions and self-interest

• What kind of tone and attitude does the author adopt?

• Authoritative/Didactic: Assuming an objective and professorial stance.

• Conversational: Speaking to the reader as a friend, or as an engaging storyteller.

• Alarmist: Representing a problem as dire and urgent.

• Does the author choose words to evoke particular emotions in the reader, such as nostalgia, lightheartedness, sympathy, or anger?

Ethos—how a writer establishes credibility and appeals to common values

• Does the writer establish his or her authority to speak on this topic?

• Bona fides: Indicating professional experience or academic qualifications.

• First person engagement: Revealing personal experience with the topic at hand.

• Substantive authority: Demonstrating expertise through the details and analytical quality of the writing.

• What specific values does the author appeal to, either explicitly or implicitly?

• Does the writer’s thesis serve his or her self-interest?

• If a professional taxi driver were to argue for banning self-driving taxis, for example, the clear self-interest in the matter would undercut his or her credibility. Arguing against one’s self-interest, on the other hand, enhances one’s ethos.

Mythos—how a writer uses elements of story to enhance his or her argument

• Does the writer characterize any person or group according to a conventional archetype?

• Does the writer use literary elements such as irony, allusion, anthropomorphism, or allegory?

Poetics—how a writer uses stylistic elements to enhance his or her argument

• Does the writer use of any of these stylistic devices to support claims?

This list is by no means exhaustive, but it provides a solid framework for analyzing the passage. In your second read-through, keep it simple. Just underline the sentences or phrases that use these devices, and categorize the devices in the margin.

Read the annotations in the sample analysis that follows and see how each underlined portion represents that particular device. Train yourself to see these devices in all of the rhetorical essays you read: newspaper op-eds, long form essays, and even your own papers.

This analysis is a critical step in writing the SAT Essay. As the scoring rubric indicates, your essay should offer a thorough, well-considered evaluation of the author’s use of evidence, reasoning, and/or stylistic and persuasive elements.

The rubric also indicates that a good essay will contain relevant, sufficient, and strategically chosen support for claims or points made. This means you must give quotations from the text that show where the author uses these particular devices and stylistic elements.

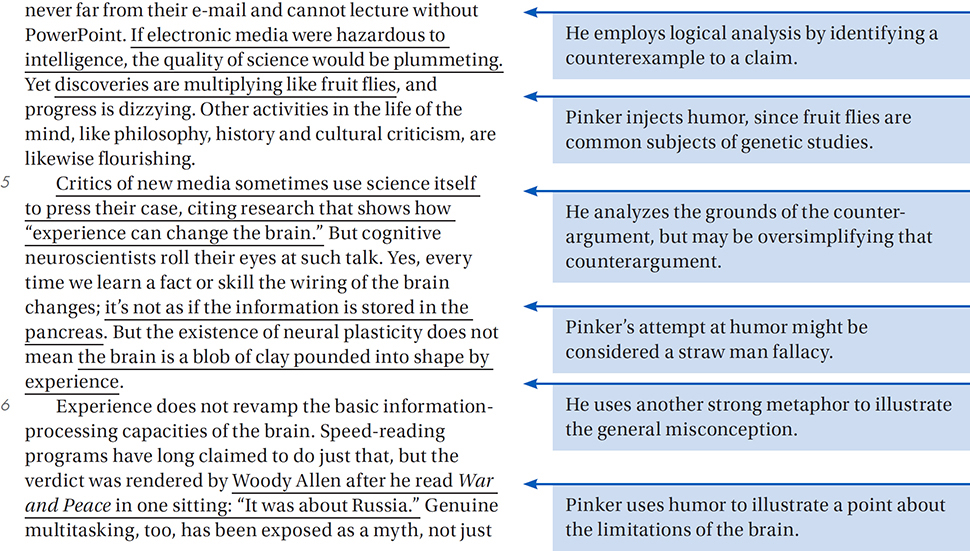

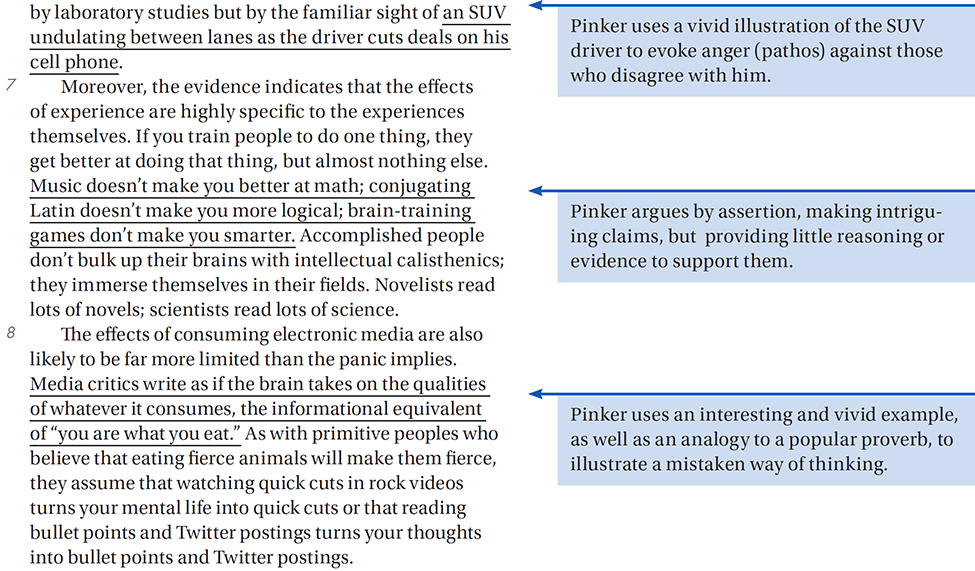

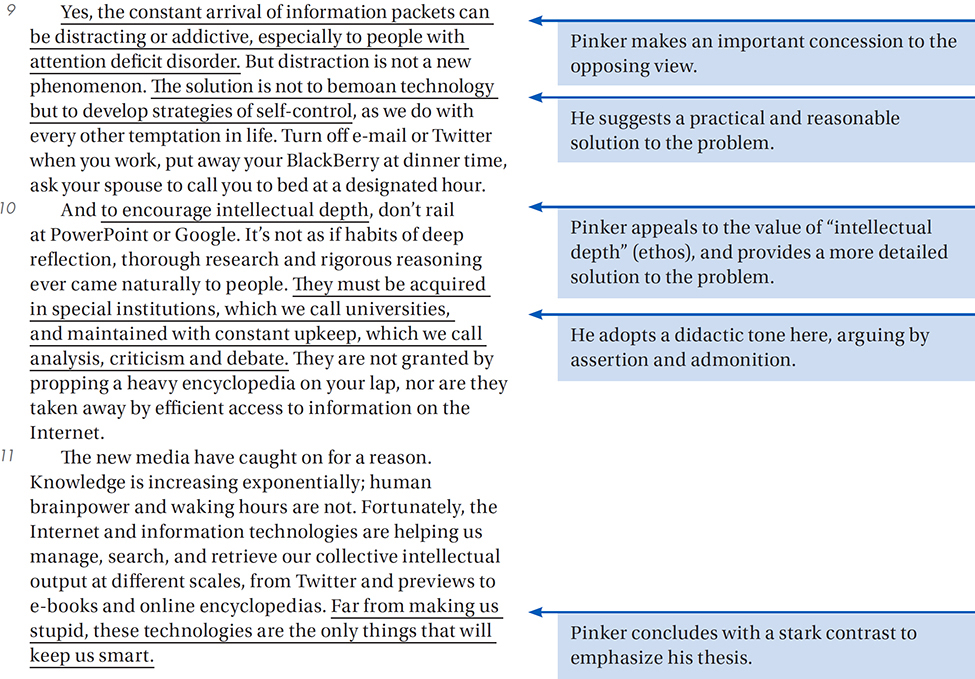

Adapted from Steven Pinker, “Mind Over Mass Media.” ©2010 by The New York Times. Originally published June 10, 2010.

Second pass: Analyze

Lesson 6: Third pass: Select and synthesize

In the third pass, read through the annotated passage again and ask: What are the three or four rhetorical or stylistic elements that contribute most significantly to the writer’s argument, and to setting the tone of the passage as a whole? Annotate the passage with this question in mind, and indicate the important examples of these elements in the text.

Adapted from Steven Pinker, “Mind Over Mass Media.” ©2010 by The New York Times. Originally published June 10, 2010.

Third pass: Select and synthesize

Construct Your Thesis and Outline

Lesson 7: Construct a precise, thorough, and insightful thesis

Once you have finished reading and annotating the text, take 10 minutes or so to craft a strong thesis and outline your essay on the “Planning Pages” provided on your test.

Take your time to construct a thesis that captures your overall analysis of the text summarize its central claim and important rhetorical and stylistic elements. Your thesis should be precise, thorough, and insightful.

Consider this first draft for our thesis:

Draft 1

In his essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” Steven Pinker looks at new forms of media. His thesis is about the reality of modern social media and the Internet. He talks about the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain.

Is it precise?

Analyze your sentences for precision by “trimming” them as we discussed in Chapter 5, Lesson 3. Trimming reduces a sentence to its core, that is, the phrases that convey the essential ideas. When we do this with our first draft, we get “… Steven Pinker looks at new forms … . His thesis is about the reality … . He talks about the misconceptions … .” Are the verbs strong and clear? Are the objects concrete and precise? Not really. Let’s look back at our notes and use quotations from the passage to make these sentences more precise.

Draft 2

In his essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” Steven Pinker looks at examines the “moral panics” about the supposed moral and cognitive declines caused by new forms of media. His thesis is about the reality of modern social media and the Internet that “such panics often fail reality checks.” He talks about analyzes the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain.

Notice that this revision better specifies what Pinker is examining in his essay by more precisely articulating his thesis, even including a quotation.

Is it thorough?

Although our second draft provides more detail about Pinker’s thesis, this draft still lacks detail about his essay’s rhetorical and stylistic elements. It could be more thorough. Let’s look back at our notes and some details about these elements.

Draft 3

In his essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” Steven Pinker examines the “moral panics” about the supposed moral and cognitive declines caused by new forms of media. His thesis, is that “such panics often fail reality checks,” is supported with historical examples, inductive reasoning, and touches of humor. He provides scientific context for his claims, and analyzes the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain.

Note that this revision more thoroughly explains how Pinker makes his points by specifying rhetorical and stylistic devices.

Is it insightful?

An insightful essay does not just indicate what elements the essay uses, but explains how those rhetorical and stylistic elements contribute to (or detract from) the argument. Your essay should NOT say whether you agree with the writer’s claims, but it SHOULD explain how the essay’s elements contribute to the effectiveness of the essay as a whole.

Think of it this way: a good movie or restaurant reviewer shouldn’t just say “Don’t go to that movie because I hate car chases,” or “Don’t go to that restaurant because I don’t like spicy food,” because a reader might actually like car chases or spicy food. Instead, a good reviewer describes the cinematic aspects of the movie or culinary aspects of the food to help the reader make a better decision. Similarly, your essay should give your reader enough information to decide for himself or herself whether Pinker’s essay is strong.

Our current draft is lacking some of these insights, so let’s add a few.

Draft 4

In his essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” Steven Pinker examines the “moral panics” about the supposed moral and cognitive declines caused by new forms of media. He uses vivid imagery to illustrate the popular misconceptions about how new media affect the brain. His thesis, that “such panics often fail reality checks,” is supported with historical examples, inductive reasoning, and touches of humor. He provides scientific context for his claims and analyzes the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain. He occasionally argues by assertion rather than providing evidence, and might be accused of oversimplifying the opposing viewpoint.

Notice that this revision discusses how particular elements of Pinker’s argument contribute to (or detract from) its effectiveness, without asserting whether or not we agree with Pinker’s central claims.

Lesson 8: Outline your essay

Now that you’ve crafted your thesis paragraph, you’re ready to outline the rest of your essay. The first paragraph “sets the agenda” for the rest of the essay. The three to four body paragraphs should develop and support each of the major points of your thesis, and the conclusion should synthesize the discussion, and perhaps analyze the overall effect of the Pinker’s essay.

Outline for Analysis of Steven Pinker’s “Mind Over Mass Media”

I. In his essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” Steven Pinker examines the “moral panics” (paragraph 1) about the supposed moral and cognitive declines caused by new forms of media. He uses vivid imagery to illustrate the popular misconceptions about how new media affect the brain. His thesis, that “such panics often fail reality checks,” is supported with historical examples, logical analysis, and touches of humor. He provides scientific context for his claims and analyzes the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain. He occasionally argues by assertion rather than providing evidence, and might be accused of oversimplifying the opposing viewpoint.

II. Pinker puts the debate in historical context by providing examples of similar moral panics from past decades, and uses inductive reasoning to imply that modern “moral panic” arguments fail for the same reason that previous examples did.

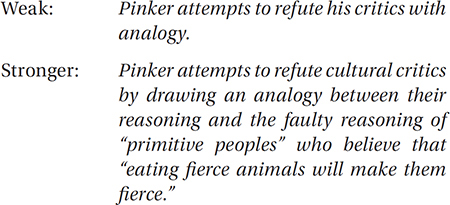

III. Pinker uses vivid images and action verbs to illustrate abstract theories about the brain, which not only clarify these concepts for the reader, but also enhance his credibility as an expert.

IV. Pinker attempts to counter moral outrage with a moral appeal of his own, to the value of “intellectual depth,” and provides practical advice for achieving that as a goal.

V. Critical readers might notice that Pinker sometimes makes bold assertions without evidence, and even accuse him of creating a “straw man” by oversimplifying the claims of his opponents. Nevertheless, Pinker addresses the attacks on modern media directly and provides an effective counterpunch.

Write the Essay

Lesson 9: Write with strong verbs and concrete nouns

Now you should have between 20 and 25 minutes left, which should be plenty of time to write your essay on the official essay sheets. As you write, keep the following points in mind in order to get a high score in the “writing” category.

Minimize weak verbs by upgrading “lurkers”

Look at a recent essay you’ve written and circle all of the verbs. Are more than one-third of your verbs to be verbs (is, are, was, were)? If so, strengthen your verbs. You cannot maintain a strong discussion if you overuse weak verbs like to be, to have, and to do.

To strengthen your sentences, upgrade any lurkers—the words in your sentence that aren’t verbs, but should be. Consider this sentence:

This action is in violation of our company’s confidentiality policy.

It revolves around a very weak verb. But the noun violation is a lurker. Let’s upgrade it to verb status:

This action violates our company’s confidentiality policy.

Notice how this small change “punches up” the sentence.

Here are some more examples of how upgrading the lurkers can strengthen a sentence:

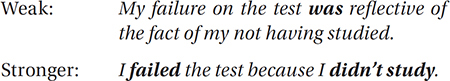

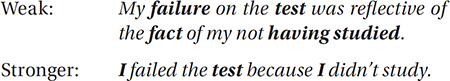

Here, we’ve upgraded the lurkers reflective (adjective) and having studied (participle). Notice that this change not only strengthens the verbs and clarifies the sentence, but also unclutters the sentence by eliminating the prepositional phrases on the test, of the fact, and of my not having studied.

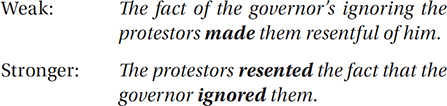

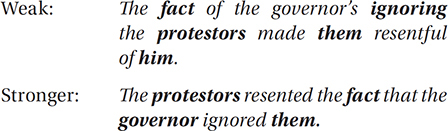

We’ve upgraded the lurkers ignoring (gerund) and resentful (adjective). Again, notice that strengthening the sentence also unclutters it of unnecessary prepositional phrases.

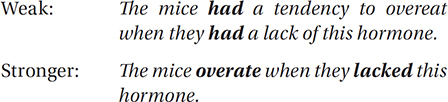

We’ve upgraded the lurkers to overeat (infinitive) and lack (noun).

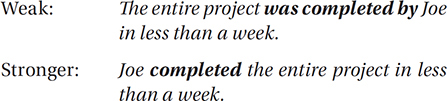

Activate your passive verbs

What is the difference between these two sentences?

The rebel army made its bold maneuver under the cloak of darkness.

The bold maneuver was made by the rebel army under the cloak of darkness.

These two sentences say essentially the same thing, but the first sentence is in the active voice whereas the second is in the passive voice. In the active voice, the subject of the sentence is the “actor” of the verb, but in the passive voice, the subject is not the actor. (The maneuver did not make anything, so maneuver is not the actor of the verb made in the second sentence, even though it is the subject.) Notice that the second sentence is weaker for two reasons: it’s heavier (it has more words) and it’s slower (it takes more time to get to the point).

But there’s an even better reason to avoid passive voice verbs: they can make you sound deceitful. Consider this classic passive-voice sentence:

Mistakes were made.

Who made them? Thanks to the passive voice, we don’t need to say. We can avoid responsibility.

Although you may sometimes need to use the passive voice, avoid it when you can. The active voice is clearer and stronger, and it encourages you to articulate essential details (like “who did it”) for your reader.

Use concrete and personal nouns

Clarify and strengthen your sentences by using concrete nouns (nouns that signify things that we can see, hear, or touch) and personal nouns and pronouns (like we, us, people, humans, anyone, and so on). Abstract nouns (like consideration, belief, ability, and information) are harder for readers to grasp than concrete and personal nouns.

When we strengthen our verbs, our nouns often become more concrete and personal automatically:

In the first sentence, 75% of the nouns (failure, fact, and having studied) are abstract, but in the second, the nouns and pronouns (I, test, I) are personal and concrete. Notice that the second sentence is clearer, more concise, and more effective.

By upgrading the gerund ignoring to a verb, we reduced the number of abstract nouns in the sentence by 50%. Even better, we upgraded the subject from an abstract noun (fact) to a concrete and personal one (protestors). The second sentence is simpler, clearer, and stronger.

Lesson 10: Create a logical flow of ideas

The official SAT Essay scoring rubric says that a strong essay must demonstrate a logical and effective progression of ideas. Therefore, make sure your essay explains each of your ideas clearly, and connects each idea to one of your central claims.

Explain your ideas

Don’t merely state your ideas: explain them clearly enough so that your reader can easily follow your analysis.

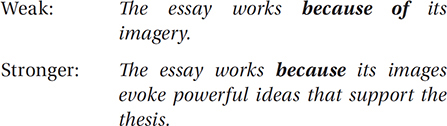

Good explanations often include words like by (our team slowed down the game by using a full-court press), because (we won because we executed our game plan flawlessly), or therefore (we slowed down their offense; therefore, we were able to manage the game more effectively).

Be careful, however, of overusing using phrases like because of and due to. These phrases tend to produce weak explanations because they link to noun phrases rather than clauses. Clauses are more explanatory because they include verbs and therefore convey more information.

Notice that avoiding the of forces the writer to provide a clause instead of just a noun phrase and therefore give a more substantial explanation.

Connect your ideas with clear cross-references

Strong analytical essays should provide clear cross-references in order to connect ideas and establish a clear chain of reasoning. One way to clarify your chain of reasoning is by using your pronouns carefully, particularly when they refer to ideas mentioned in previous sentences. Make sure your pronouns have clear antecedents.

Consider these sentences:

Davis makes the important point that defense lawyers sometimes must represent clients whom they know are guilty, not only because these lawyers take an oath to uphold their clients’ right to an adequate defense, but also because firms cannot survive financially if they accept only the obviously innocent as clients. This troubles many who want to pursue criminal law.

What does the pronoun This in the second sentence refer to? What troubles many who want to study criminal law? Is it the fact that Davis is making this point? Is it the moral implications of lawyers representing the guilty? Is it the technical difficulty of lawyers representing the guilty? Is it the financial challenges of maintaining a viable law practice? Is it all of these? The ambiguity of this pronoun obscures the discussion and makes the reader work harder to follow it. Clarify your references so that your train of thought is easy to follow.

Davis makes the important point that defense lawyers sometimes must represent clients whom they know are guilty, not only because these lawyers take an oath to uphold their clients’ right to an adequate defense, but also because firms cannot survive financially if they accept only the obviously innocent as clients. Such moral and financial dilemmas trouble many who want to pursue criminal law.

Connect your ideas with logical transitions

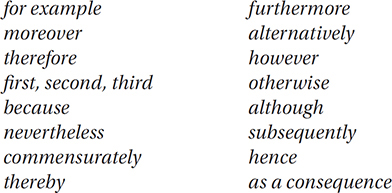

As you move from idea to idea—within a sentence, between sentences, or between paragraphs—always consider the logical relationship between these ideas, and make these connections clear to your reader. The logical “connectors” include words and phrases like

Structure each sentence to fit its purpose

According to the official SAT Essay scoring rubric, a strong essay uses an effective variety of sentence structures. Short sentences have impact; long sentences have weight. Good writers vary the structure of their sentences to fit the purpose of that particular discussion.

Consider this paragraph:

Medical interns are overworked. They are constantly asked to do a lot with very little sleep. They are chronically exhausted as a result. They can make mistakes that are dangerous and even potentially deadly.

What is so clumsy about these sentences? They all have the same structure. Consider this revision:

Constantly overworked and given very little time to sleep, medical interns are chronically exhausted. These conditions can lead them to make dangerous and even deadly mistakes.

Your readers won’t appreciate your profound ideas if your sentences are poorly constructed. Now consider these sentences:

Gun advocates tell us that “guns don’t kill people; people kill people.” On the surface, this statement seems obviously true. However, analysis of the assumptions and implications of this statement shows clearly that even its most ardent believers can’t possibly believe it.

Now consider this alternative:

Gun advocates tell us that “guns don’t kill people; people kill people.” On the surface, this statement seems obviously true. It’s not.

Which is better? The first provides more information, but the second provides more impact. Good writers always think about the length of their sentences. Long sentences are often necessary for articulating complex ideas, but short sentences are better for emphasizing important points. Choose wisely.

Sample Essay

Analysis of Pinker’s “Mind Over Mass Media”

Here is our final essay for the Pinker Op-Ed. Notice that we include plenty of quotations from the text to support our claims, complete with paragraph numbers, and that each paragraph simply “fills in the details” from our outline.

In his essay, “Mind Over Mass Media,” Steven Pinker examines the “moral panics” (1) about the supposed moral and cognitive declines caused by new forms of media. He uses vivid imagery to illustrate the misconceptions about how new media affect the brain. His central claim, that “such panics often fail reality checks” (3), is supported with historical examples, logical analysis, and touches of humor. He provides scientific context for his claims, and analyzes the misconceptions that cultural critics have about the relationship between modern media and the human brain. He occasionally argues by assertion rather than providing evidence, and might be accused of oversimplifying the opposing viewpoint.

Pinker puts this debate in historical context by giving examples of similar moral panics from past decades, and uses inductive reasoning to show that the new arguments fail for the same reason that the old ones did. He says that new forms of media “have always caused moral panics” (1) but that these panics have not been based in reality. He says that “comic books were accused of turning juveniles into delinquents in the 1950s” (3) and that similarly “television, transistor radios and rock videos” (3) were supposed to be rotting young minds, but that really “IQs rose continuously” (3) during those periods.

Pinker uses strong action verbs to illustrate theories about how the brain works, clarifying these concepts for the reader and also enhancing his ethos as an expert. He says new media opponents are afraid that these technologies make us “skim on the surface of knowledge rather than dive into its depths” (2) and cause the quality of scientific thinking to “plummet” (4). But in fact, Pinker says, scientific discoveries are “multiplying” and progress is “dizzying.” When he describes how the brain processes information, he uses verbs like “pounded” (5) and “revamp” (6). These lively action verbs help the reader to see the different sides of the argument, and they show that Pinker understands the issues very well, enhancing Pinker’s ethos as a writer.

Pinker attempts to counter moral outrage with an appeal to the value of “intellectual depth” (10), and provides practical advice for achieving that goal. This is helpful to readers who want to do more than understand the brain, but also want to make people smarter. He tells us that intellectual skills are developed “in special institutions, which we call universities, and maintained with constant upkeep” (10).

Some readers might object that Pinker sometimes makes claims without evidence, such as “music doesn’t make you better at math” (7). They might also accuse him of creating a “straw man” by oversimplifying the claims of his opponents, like when he says “yes, every time we learn a fact or skill the wiring of our brain changes; it’s not as if the information is stored in the pancreas” (5). Nevertheless, Pinker addresses the attacks on modern media and gives an effective counterargument.

Scoring

Reading—4 out of 4

This essay demonstrates a strong comprehension of Pinker’s central claims, using summary, paraphrase, and quotations. It summarizes Pinker’s central thesis, modes of argument, and tone (His central claim, that “such panics often fail reality checks,” is supported with historical examples, logical analysis, and touches of humor). The quotations are carefully chosen to illustrate the central ideas of Pinker’s argument, and are accompanied by relevant and accurate commentary.

Analysis—4 out of 4

This essay provides a thoughtful and critical analysis of Pinker’s argument and style, demonstrating a strong understanding of the analytical task. The essay identifies Pinker’s primary modes of expression (historical examples, logical analysis, and touches of humor), examines his mode of reasoning (inductive reasoning), and even identifies possible gaps in his argument (assertions without evidence … “straw man”) without taking a side for or against Pinker’s thesis. It also provides substantial textual evidence for its claims, and demonstrates a strong understanding of Pinker’s rhetorical task.

Writing—4 out of 4

This essay shows mastery of language, organization, and sentence structure. It remains focused on a clear central claim, and develops its secondary claims in well-organized paragraphs. It demonstrates effective variation in sentence structure and generally appropriate word choice. Largely free from grammatical error, this essay demonstrates strong command of language and proficiency in writing.