“Somewhere in this industry this has happened before.”

ROGER STERLING MAD MEN

It was the best of times, it was the best of times. To be white, male, and healthy in New York in the 1950s was to be as blessed as any individual at any time in history. The booming wartime economy had given way to a booming peacetime economy, fuelled by full production to meet the voracious demand from buyers nourished by the innovation and choice now available in their bounteous new “supermarkets.”

One almost unbelievable statistic indicates just how the city experienced its own stampede by the business community; between 1950 and 1960 more new office space was added to New York than existed in the rest of the world at the time. In one decade that one city more than doubled the world’s available office space. And all of it went upward, transforming, for example, midtown Park Avenue from a sedate backwater of domestic brownstones into a vast glistening river of glass and steel.

While Europeans still shivered, exhausted, in their damp monochrome deprivation in the aftermath of the ruinous war, New Yorkers assumed world leadership with a cool sophistication that they’d previously granted to Paris, Rome or London. In the excited, urgent chatter in the new air-conditioned offices, in the packed bars and increasingly worldly restaurants, in the crammed theater lobbies and Fifth Avenue stores there was a new confidence gained from global domination. New Yorkers basked in the health and wealth reflected back at them in the glass and chrome of their elegant, bustling streets. They revelled in their status as citizens of the busiest, noisiest, fastest growing, most advanced, most cosmopolitan, coolest, most desirable, and most photogenic city in the world.

As “the highway between those two most powerful forces known to man, supply, and demand,” advertising was on the crest of a wave too. Between 1949 and 1959, total advertising spending more than doubled, from $5.21 billion to $11.27 billion. As a measure of what mattered to people, the top twelve advertisers mid decade included three car manufacturers (General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler); three hygiene and personal grooming companies (Proctor & Gamble, Colgate-Palmolive, and Lever Brothers); two food marketers (National Dairy Products, including Kraft, and General Foods); two electrical goods giants (RCA and Westinghouse—mainly producers of radios, television sets, and radiograms); and an alcohol producer (Seagram).

The money was split more or less equally among magazines, newspapers, and radio. Television wasn’t a serious contender for advertising spend until later in the decade, the proportion of households with a television set rising from 10 percent in 1950 to 90 percent in 1960.

WITH THIS MASSIVE expansion in media activity, advertising came under public scrutiny more than ever, and plenty of the comment was not favorable. Arthur Schlesinger, Special Advisor to President Kennedy, had called advertising “awful.” Arnold Toynbee, a British historian, complained, “I cannot think of any circumstances in which advertising would not be an evil.”

Advertising’s own practitioners seemed only too happy to stick the boot into the business. Nearly a dozen novels published in the fifties featured hollowed-out advertising employees, filled with self-loathing for what they did, including Aurora Dawn, the first novel by Herman Wouk (featuring a fictitious ad agency, Grovell & Leach—there’s a giveaway). All but one of these novels were written by people either in, or closely allied to, the advertising business.

The Hucksters, written by copywriter Frederic Wakeman, is a typical example. The novel was filmed in 1947 with Clark Gable in the starring role of advertising executive Vic Norman, working on the Beautee Soap account. It chronicles dirty tricks, flesh-creeping client obsequiousness, and all-encompassing contempt; contempt for the consumer, for colleagues, for the advertising business, and for himself. Initially Gable didn’t even want the role, describing it as “filthy and not entertainment.”

Vic Norman’s client is the unspeakably vulgar autocrat Evan L. Evans. He was based on George Washington Hill, the Lucky Strike client of Foote, Cone & Belding where Wakeman worked when he wrote the book. At one point, in a demonstration of his advertising philosophy, Evans spits on the conference table and says, “You’ve just seen me do a disgusting thing—but you’ll all remember it.” To make the same point Hill had once pulled out his dental bridge in front of Raymond Rubicam, his account director on the Pall Mall account. He told him this was how he amused his granddaughter, and that engaging the public was no different.

In Sloan Wilson’s The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit, a title which for at least two decades supplied a shorthand to describe admen’s dress (inaccurately, as it happened, as in the 1950s they preferred the more buttoned-down, dark-suited Wall Street look of Brooks Brothers), Gregory Peck plays Tom Rath, a PR man and mentally scarred World War II veteran who leaves a job in the charity sector to work for a TV network. Increasingly disillusioned with the job, the politics, the surrounding inertia, and the suspect morality, Rath leaves the business to lead a less pressured, more family-centered life.

ADVERTISING WAS ALSO fair game for a kicking as screenwriters jogged by on their way to bigger themes. In the 1957 Sidney Lumet film Twelve Angry Men, the cheesily handsome juror who seems least in touch with reality and most prepared to change his mind just had to be in advertising; even in lighthearted mode, the husband in the long-running early sixties TV series Bewitched was a permanently bewildered advertising executive, with an obsequious client-pleasing boss, while the romantic romp Lover Come Back sees Doris Day trying to get even with rival agency head Rock Hudson for his unethical tactics in stealing a client.

Elements of these portrayals must have been true. Certainly, advertising was wearing and mentally draining; apart from anything else, ad men worked extraordinarily long hours, often with detrimental effect on their health; an Advertising Age survey reported in 1956 that senior advertising executives died at an average age of 57.9, ten years under the national average. In addition, the unpredictable nature of the business generated constant anxiety over client loss and the immediate brutal consequences. In return, the rewards were high, with admen earning anything up to 50 percent more than their equivalents in other businesses. But that of course is a double-edged sword: the more you’re paid, the more you have to lose. “Ulcer Gulch” became a sardonic way of referring to Madison Avenue.

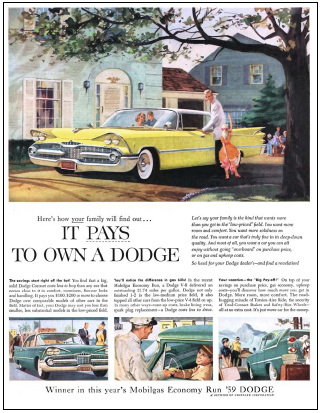

Acres of crunchy gravel, miles of smiles; there was the real world and there was the world of auto advertising.

The fabled expense account lifestyle, too, was often anything but glitzy for the agency man. It wasn’t always a boozy lunch or night with his friends and colleagues from around the business. This genuinely was the era of the three-martini lunch and five-course dinner, and the ad executive ate and drank them whether he wanted to or not. It all depended on the client, who frequently viewed a trip to his agency as light relief from what was often a humdrum life somewhere in middle-America, far from the bright lights of the most fabulous city on earth.

He could look forward to a couple of days in a swanky New York hotel, a visit to the agency with the opportunity from reception onward to ogle some fine legs and even finer busts. There would be a well-catered meeting in the agency’s sumptuous conference room, maybe enlivened by the presence of some of the menagerie otherwise known as the creative department, in which he could beat up or lift up the agency depending on his mood. Business out of the way, there’d be a big lunch at Nino’s or Rattazzi’s—where the standard martini glass was eight ounces—followed by an afternoon spent shopping, then cocktails with the agency at the Algonquin, a show, and dinner at 21 or Copacabana. Then a club—perhaps a clip joint—before heading back to the Midwest or the South the next day, and all without so much as a glimpse of a bill at any time, day or night.

Great for the client once in a while—but four days a week for the account men with their fixed smiles, ready jokes, and the ever open wallet, it was liver-destroying purgatory.

Obsequiousness and double dealing are sadly inevitable in an unregulated service industry, and advertising was never going to be an exception—at least until the end of the fifties. Unprotected by guilds or freemasonry or professional codes, it was still a free-for-all less than sixty years from its raw-boned frontier days as a media broking business.

AS AN INDUSTRY, advertising had waxed and waned with national events. Its first great boom came after the Civil War, another was induced by World War I; helplessly tied to the market it slumped in the Depression, then picked up with the growth of mass production and greater availability of goods. The subsequent introduction of self-service, when the housewife could no longer necessarily take advice and comfort in the words of the storekeeper as her personal shopper, created a demand for more paid-for public advocacy. Which is as good a definition of advertising as any.

Early advertising agencies in the 1800s simply sold space in newspapers to advertisers, buying column inches from the publishers either directly for their customers or for themselves to sell later on. Few, if any, rate cards were published, and ignorance abounded—ignorance of the true prices, value, readership, reach, influence, even of how many newspapers there actually were.

What made it even more unruly was the fact that while the agencies charged their customers a commission, they also regularly took kickbacks from the newspapers, or at best didn’t pass on discounted rates. From their point of view it wasn’t so much a conflict as a confluence of interest. While ostensibly acting in pursuit of a better deal for their customers, it was clearly to their advantage to spend as much as they could of their customers’ money; the customer-derived commission, based on a percentage, was higher, and their “reward” from a grateful newspaper was greater. What appeared on the space the agencies were broking was none of their business—the actual content of the ads was usually supplied by their customer.

But gradually, order emerged from the chaos as common and business sense combined to bring clarity to the practice. In Philadelphia, in 1869, George P. Rowell brought out the first ever comprehensive guide to media rates. Rowell’s American Newspaper Dictionary enabled a client to plan and buy their media from a substantial choice of publication styles, locations, and readership profiles. It included circulation figures, and the immediate availability of such information undermined the hucksterish behavior of the contemporary advertising agencies. Worse for them, such transparency threatened their very existence as a client could now do for himself what he’d previously needed their “insider knowledge” and “expertise” to achieve.

To survive the agencies had to offer more, and this took the form of creative services—advice on how to prepare and write the ads. They would charge for the space plus the costs of creating the ad, and thus the model for the advertising agency of the twentieth century—an organization that will advise you on not just where to place your advertisements but what to say in them, and then produce those ads—was created.

It would contain media specialists, creative people (both writers and artists), and account managers or executives to liaise between the clients and the agency staff. Those early agencies employed quite a few of their copywriters from a field force of freelancers that had grown up working directly for clients. They cut their teeth on retail store advertising, some toiletries and hardware products, and particularly patent medicines—quack remedies sold in vast numbers throughout the United States.

The market for these remedies was huge, partly assured by the fact that many of the potions included alcohol or even opium, a legitimate way around temperance for those who were pious enough to be claiming abstention. The inventiveness of the manufacturers and the copywriters in coming up with increasingly vague scary diseases and afflictions that only they could fix was unbounded, preying on the fears of a simply-educated and gullible public. And the margins on these potions, which were often, apart from the alcohol, little more than colored water, were so vast that the producers could afford to spend large sums on promoting their products. They had found that the reassurance and promised salvation in the advertised testimonials from “doctors” and the “cured” proved highly effective. As Stephen Fox reports in The Mirror Makers, one such patent medicine proprietor claimed, “I can advertise dishwater and sell it, just as well as an article of merit. It’s all in the advertising.” It’s hardly surprising that, with ethics like that, and with the reputation it had gained in its early days, advertising was still seen as a far from respectable activity.

HOWEVER, THE INDUSTRY was maturing, though that was not always driven by the agencies. In 1892, the Ladies’ Home Journal had banned patent medicine ads, and growing organizations like P&G and Kellogg took pride in their probity. They were selling wholesome products for wholeseome families and they simply would not tolerate suppliers of ill-repute. So by the 1950s many agencies were fiercely honorable, renowned for watertight integrity, J Walter Thompson (JWT) being a prominent example. In 1955, Jeremy Bullmore, a young copywriter from JWT London was sent to the New York office to learn about making TV commercials—in the run up to their first appearances on UK television in 1955 no one there had any idea how to write or make them. Before he left for the fourteen-hour flight, the only advice he was given by his boss was “get your hair cut and don’t wear suede shoes.” Apparently the British thought that, to New Yorkers, suede shoes were a sign of gayness.

He found the Lexington Avenue office in the Graybar Building an austere place, far from the image of Mad Men’s Sterling Cooper.

“There were a lot of very serious account people, all highly intelligent but serious; they were grown-up, they didn’t have a lot of fun. They were very well-educated but it was much more like an agreeable law firm, not an agency. Nobody questioned the fact that you were there to use your brains on your client’s behalf, that absolutely didn’t need to be said. They took the business very seriously; I mean it, I’m not sure the word creative was used at all. There was the art department and the editorial department, which was the copy department, showing its origins in journalism. And the lady copywriters sat in their own compounds, wearing hats.”

Hats seem to have been big, particularly with the women at JWT. Wally O’Brien, an account man, recalls the midweek queue outside the New England Room (a boardroom that resembled the kitchen of a New England farmhouse, a JWT feature dating back to pre-war days). “Wednesday was ‘Women’s Day,’ when only women could eat in the room, and they’d vie with each other to wear the most outrageous hat to lunch. We’d stand outside to see them go past on their way in!”

The agency wouldn’t accept an alcohol or cigarette account and they’d never pitch for new business competitively or speculatively, on the argument that they couldn’t put forward responsible recommendations until they had a real, deep understanding of the client’s market.

Alcohol consumption in the office was almost unheard of. And ever since Reader’s Digest published its 1952 “Cancer by the Carton” article, examining possible links between tobacco and cancer (long before the 1964 Surgeon General’s report on the effects of smoking on health), several agencies refused to handle tobacco, extraordinarily lucrative though it was. Several prominent figures called for it to be banned and plenty more dropped it on the announcement, including both Bill Bernbach and David Ogilvy. Indeed, the head of McCann-Erickson, Emerson Foote, resigned because his agency continued to handle cigarettes.

So the business wasn’t without its principles and principled people. Nevertheless, the novelists were right in their portrayal of a group of people who, rightly or wrongly, were riddled with low self-esteem. Reported in a lengthy essay in Time magazine, late in 1962, only 8 percent of admen polled believed that their fellow admen were “honest.” Indeed, so much self-examination and self-flagellation was going on that the president of the American Association of Advertising Agencies urged his members to stop “staring into the mirror to count the pimples, broken veins, and wattles on the serene, handsome, and competent face we hope to present to the public.”

IN 1957, one book, Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders probably did more damage to the reputation of advertising than any other single tangible factor. It claimed to expose practices within the advertising business of subconscious coercion, subliminal advertising, and wonderful and weird techniques that either forced us to surrender our innermost thoughts, fears, and desires, or got us all buying products without ever realizing why we were doing it.

Clearly a sensation-seeking writer—Time magazine in 1962 described Packard as “one of the nation’s most talented self-advertisers”—his book promoted the discomfiting notions, wheezes, and theories of the quack psychologists and pointy-bearded analysts who were besieging agencies with quick-fix nostrums derived from consumer motivational research, depth psychology, and other psychological techniques.

To be fair to Packard, these people and their ideas (among them Ernest Dichter, a Viennese psychologist with a Freudian-based résumé, who set up shop in a Manhattan suburb to promote his newly created “science” of motivational research) did exist, and in trying to get business from clients and agencies they probably were making the claims he reported. But that doesn’t mean they were actually being implemented, let alone the least bit effective or successful. As most people who have ever worked in an agency for any length of time will tell you, it’s far more a matter of intuitive trial and error than finely tuned science.

Yet the book, perhaps preying on the paranoia of a fearful nation, engaged in the Cold War and fed fanciful science-fiction tales of invisible rays and undetectable brainwashing, was a bestseller for six months, exercising almost supernatural power over its readers. In 1966, Victor Navasky, now a professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, wrote for The New York Times: “In the thirties, economists knocked advertising. In the forties, novelists knocked advertising. In the fifties, sociologists knocked advertising and Hollywood began making movies out of the novels of the forties. In the sixties, the politicians who saw the movies began to attack advertising.… It has been attacked for ‘arousing anxieties and manipulating the fears of consumers to coerce them into buying’ and at the same time it has been dismissed as impotent, misdirected, and irrelevant.”

The final nail? Some time in the mid fifties, Webster’s dictionary changed it’s definition of “huckster” from simply “hawker, peddler” to add “one who produces promotional material for commercial clients, particularly radio and newspapers.” The humiliation was complete.

The real cause of discontent, both internal and external, was the advertising itself. By and large, it was execrable. To make matters worse, the more the economy boomed, the more there was of it to see.

A 1962 Time article stated, “Many admen tend to ascribe much of the responsibility for television’s excesses to one source: Manhattan’s Ted Bates & Co, which funnels a greater percentage of its business into TV than any other agency (80 percent) and has rocketed from nowhere in 1940 to fifth place among all US agencies.… The enfant terrible at Bates is Chairman Rosser Reeves, fifty-two, who propagated the dogma of the Unique Selling Proposition, or USP. The rule: find a unique proposition that promises a specific benefit to the customer and will thereby sell The Product… the agency hammers it home with water torture repetition.”

IF, FOR GENERATIONS OF CREATIVE people, Bill Bernbach is their Redeemer, no one more than Rosser Reeves best personifies the antiChrist. By his invention and implementation of the USP, Reeves probably had as huge an influence on the course of advertising as his contemporary, but in the diametrically opposite direction.

Actually, the problem so many ad people had with Reeves was not so much the USP itself, it was the way he went about implementing it and his utter indifference to the wider effect of his advertising on the public.

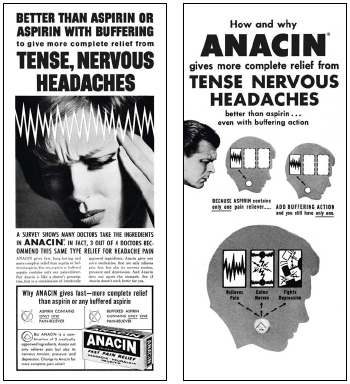

One of his most notorious commercials was for Anacin: hammers banging away at the inside of a cartoon head. It ran unchanged for seven years and when you’d seen it once you never needed or wanted to see it ever again. That it must have cured millions of headaches there can be little doubt, as sales tripled and the advert made more money for Reeves’ client, as he liked to point out, than Gone with the Wind, on a production budget of just $8,200. The media spend over that period was $86,400,000, a staggering amount for the era. The question that never bothered him was how many headaches it, and so many others of his commercials, caused.

A story he liked to tell clients says it all. A farmer buys a mule that he finds to be unusually stubborn and simply won’t get going. He takes it to an old farmhand who is said to know everything there is to know about mules. For $5 he says he can fix it. The money changes hands and the old man picks up a 45-pound hammer and hits the mule as hard as he can, right between the ears.

“Hey,” says the owner, “I paid you to cure him, not kill him!”

“I know,” says the old man, “but first I have to get his attention.”

Hit them hard, straight between the ears, painfully, mercilessly—and keep hitting them until they give in. Boring, repetitive commercials, usually featuring quasi-scientists in white coats or basic graphic devices with a voice-over slamming home a product virtue—over and over again: “Four out of five doctors…”

Typical of this “monkey see, monkey do” approach was a commercial for M&Ms, focusing on the utilitarian point that the candy doesn’t melt in the hand. Two closed fists were shown, the viewer asked to guess which hand holds the M&Ms. Then they’re opened and one is messy, and a grinning presenter helps us to the desired conclusion.

Tense, nervous headache? Examples of Rosser Reeves’ campaign for Anacin.

The same 1962 Time article continued, “the average American is now exposed to ten thousand TV commercials a year. As the number increases, so do the admen’s worries about ‘overexposure.’”

There had been plenty of opportunity for overexposure before, in the heyday of radio. But the new intrusiveness of television, which demanded (and got) both ears and eyes, together with the repetitiveness of the new thirty-second TV commercial format meant that “most admen profess to detect evidence of… more vocal public irritation with strident or tasteless ads.”

Even more uncompromising, Fairfax Cone, his own agency a big TV spender, said to the Federal Communications Commission, “The great mass of television viewers are treated to an almost continuous program of tastelessness, which is projected on behalf of competitive products of little interest and only occasional necessity.”

Bear in mind, this was before the remote control and there was no way of changing channel or switching off without actually getting off the couch and walking to the set. Norman Strouse, then president of JWT, worried, “It is a simple matter to turn a page but TV makes it possible for advertisers to impose rudely on the viewer with every unhappy practice of the industry—hard sell, bad taste, driving repetition.” And the more they saw of it, the more the public disliked it.

YET REEVES HIMSELF was the polar opposite of the crude salesman and media hooligan that his legacy would suggest. Born in 1910, he was the son of a Virginian minister and a graduate of the University of Virginia. It seems he viewed advertising simply as an activity to make money to enrich his leisure time, and his leisure time was as cultured as his output was uncouth. It was as if there were two Reeves.

Living in Greenwich Village during the beatnik era, he was a poet, a novelist, a keen racing yachtsman and pilot, and, testament to tremendous concentration and analytical powers, captain of the 1955 US chess team picked to play Russia. He was good company, quick-witted, and whilst normally showing a calm poise, he also occasionally betrayed a disarming enthusiasm once he got his teeth into something. His interests even extended to being part of a consortium of eleven Southern businessmen, mainly Brown and Williamson tobacco executives, who “owned” Cassius Clay (later Muhammad Ali) in the early days of his career.

“What do you want out of me? Fine writing? Do you want masterpieces? Do you want glowing things that can be framed by copywriters? Or do you want to see the goddam sales curve stop moving down and start moving up?”

ROSSER REEVES

A huge believer in research and analysis, he passionately held that entertainment or charm in advertising were not just unnecessary but undesirable, describing them as “video vampires.” And any departure from an agreed proposition, even in a small detail, was to be avoided.

In 1961, Reeves’ philosophy, and guidance on its implementation, was collated into his book Reality in Advertising, which was originally written as a document for executives joining the agency, releasing a torrent of imitative commercials—repetitive, didactic, fact-rich, and entertainment-poor. Uncertain clients, finding reassurance in text books that gave “theories” of advertising a quasi-academic respectability, and looking for risk-free creative “solutions,” embraced the technique. And as so much TV advertising around the world was for companies exclusively led from the United States, it quickly became the style of the first advertising that most of the world would experience on their televisions. Any criticism of his methods would have been robustly kicked into the long grass.

“Getting the message into the most people at the lowest possible cost, well, it’s almost a problem in engineering, and we should subordinate our own creative impulses to that one overall objective. Does this advertisement move an idea from the inside of my head to the inside of the public’s head? The most people at the lowest possible cost? What else is this business about?… It’s a technical job.”

Reeves had a point; Bates was almost exclusively a packaged goods agency and despite the antipathy it created, not just for its own sake but for all advertising, clearly a lot of the time his utilitarian advertising for those low cost, functional products was effective. Companies like P&G adopted it as the only way in which they wanted their advertising to be conducted.

This was the era of constant product innovation, when new variations of medicines, shaving products, hair shampoos, skin creams or foods were flooding the market, to the potential bewilderment of the public. It’s easy to understand that advertising, which was little more than a shouted bulletin board, was often the most efficient way to elevate your pitch above the daily cacophony. And its charisma-free directness was the quickest way to explain the benefits of, say, the previously unheard of product now being sold as hair conditioner.

But many inside advertising would argue that this soulless hard-sell approach was working for its advertisers at the expense of advertising as a whole. This certainly was not the era when the consumer would claim to prefer the commercials to the programs.

It took the likes of Reeves’ even more famous brother-in-law, not always one of his greatest fans, to both lighten and soften the advertising mood.