‘I know the copywriters tell the art directors what to do and the account executives tell the copywriters what to do.’

PEGGY OLSEN MAD MEN

Reeves once warned against originality, citing it as ‘the most dangerous word of all in advertising’, and every day that belief was enforced throughout Madison Avenue, to the detriment of the work and dismay of the creative people. Their lives were ever more driven by research, which in turn reinforced the status quo, since only that which already exists could be researched. Add to that their servility to clients who were happy only with the familiar, and it’s inevitable that originality would be stifled.

In most agencies the creative work was merely a functional job. The power within the organisation rested with the account people, those who fronted the agency and liaised with the client. It was they who brought the requisition for the campaign to the copywriters, they who frequently decided the particular strategic platform on which the ads had to be built, they who judged whether or not they wanted to present it to the client, and they who eventually did so.

Next came the writers. Received wisdom had it that advertising was ‘salesmanship in print’ and as salesmanship was spoken sales patter, it followed that the ‘word’ had primacy over pictures. At the bottom of the heap were the art directors or visualisers, whose opinion was rarely sought, who hardly ever received the brief and never met the clients. They did the writers’ bidding, usually simply executing his or her instructions as to how the ad should be laid out and illustrated.

Not even the creative director had much of a say, and few had the autonomy of Don Draper at Sterling Cooper. It was the account men – almost exclusively men – who were the judge and executioner on all creative work, with the power to reject, edit and even personally rewrite if they so wished. The account executive, like an obsequious waiter grovelling to a valued diner in a bad restaurant, took the order to the creative kitchen who served up exactly what the client wanted – usually what he’d had the day before and the day before that. And if the client wanted ketchup on his sea bass, then the waiter saw to it that the kitchen people damn well gave him ketchup on his sea bass.

ALL THIS CHANGED on 1 June 1949, when Bill Bernbach, together with Maxwell Dane and Ned Doyle, opened Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB). To decide the running order for their names in the agency title, they’d tossed a coin. They also agreed on doing away with the commas that usually ran between proprietary names: ‘Nothing will come between us, not even punctuation’, said Bernbach. The agency was twelve people in all and they started what would remain one of the two biggest upheavals in advertising until the growth of the Internet – the upheaval now known as the Creative Revolution.

Bill Bernbach’s philosophy was so radical it was almost incomprehensible: ‘We have no formula at all. The only common denominator in our ads is that each one has a fresh idea. We present the story in a fresh and original way.’ Agency writers, and particularly art directors, constrained in the executional straitjacket of a Reeves or Ogilvy dogma, found it astonishingly liberating.

For Bernbach it had been a comparatively short haul in advertising from fledgling copywriter to agency owner. Born in 1911, one of four children to Russian and Austrian Jewish middle-class parents, and brought up in the Bronx in an unremarkable childhood, he went on to study music, philosophy and business administration at NY. It was as good a mix as any for a future in advertising, although at the time that was far from his intention.

He left university in Depression-shrouded 1932 and he took a job his father had arranged for him in the mail room of a local brewery, Schenley Distillers. While he was there, he took to creating ads for Schenley’s American Cream Whiskey, almost little more than doodling, and sent them off to the company’s agency, Lord & Thomas. A few months later he was amazed to see one of his ads in a paper.

‘I had gotten to know [Schenley President] Rosenstiel’s secretary… and she took me under her wing, and a very powerful wing it was too,’ he recalled in Bart Cummings’ The Benevolent Dictators. She encouraged him to establish credit for the ad by visiting L&T to see if he could look through their files to find a copy of the letter he’d enclosed with his suggested ad, proving it was his idea.

‘I was reading a book of poetry at the time, Kahlil Gibran, a romantic Indian poet that I, at that moment, was in love with. And I went to call on this girl who was in charge of the files up at Lord & Thomas and she said, “What are you reading?” I showed it to her and, lo and behold, she was a devotee of Kahlil Gibran. So she went to the files and sure enough, there was the letter.’ The upshot was a job in the marketing department at Schenley, and Bernbach’s career in advertising was launched.

MAJOR EVENTS WERE also developing in his personal life, described by Doris Willens in Nobody’s Perfect:

‘The Twenty-first Amendment to the Constitution had been ratified on December 5th, 1933, repealing Prohibition. Ex bootleggers turned into distillers. At the young Schenley company, headquartered in an elegant midtown brownstone, Bill wrapped bundles of ‘The Merry Mixer’, a promotional brochure of cocktail recipes much in demand across wet again America. A young Hunter College graduate, Evelyn Carbone, addressed the labels, often glancing up to see if Bill, as he often did, re-buried his head in a book. She loved his passion for books, seeing him as a kindred spirit in a coven of bootleg-era survivors.’

Fairly soon they were seeing each other regularly and the increasing warmth of his welcome in the Carbone family was in inverse proportion to the freeze he experienced in his own home. His mother could not reconcile herself to the idea of her children ‘marrying out’ and was implacable in her hostility to the relationship. Increasingly, Bernbach was swapping a Jewish life in the Bronx for an Italian one in Brooklyn, and in 1938 he made the break final by eloping and marrying Evelyn before a Justice of the Peace.

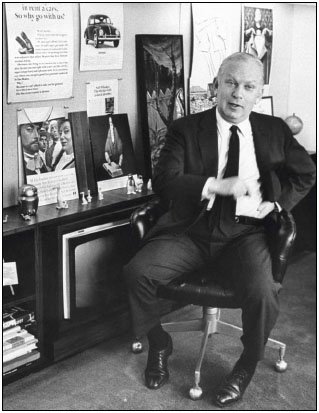

Bill Bernbach in his office in 1966 with several famous DDB campaigns shown behind him.

Meanwhile, his career had been given a massive leg-up by the larger-than-life figure of Grover Whalen, an alleged PR and marketing expert, who had been New York City’s police chief during Prohibition and who had subsequently joined Schenley as Chairman of the Board.

In 1935 Whalen was put in charge of organising the New York World Fair that was to open in 1939, and he took the young Bill Bernbach with him to work in his offices in the Empire State building and at the site in Flushing Meadows. In May 1939, Time reported, ‘the fair as it stands today – a $157,000,000 extroversion of Mr Whalen’s fantastic extrovert personality – gives him fair claim to the title of the greatest salesman alive today’.

The proximity to such a central character in New York business life, together with the experience gained in dealing with the corporate sponsors, press and politicians, was a fast track for the young Bernbach fresh out of a small company marketing department. And as his primary function was in creating publicity – he claimed to have written speeches for Whalen and ‘many prominent people’ – his grounding in commercial communications continued on a broader scale.

But when the fair wound up in 1940 Bernbach had to start all over again. Now with a taste for advertising – he said, ‘I thought it might be a good idea to ghost for some products instead of people’ – he looked for a job as a copywriter. Evelyn was still working for Schenley’s, and through her Bernbach was introduced to William Weintraub, the owner of the agency that handled Schenley’s advertising.

Up against two qualified rival candidates and with no actual advertising work to show, Weintraub asked Bernbach to write him a letter justifying why he should be chosen. The letter did the trick.

BY HAPPY ACCIDENT Bernbach was assigned to work with Paul Rand, one of the greatest figures in US commercial art and on his way to becoming a godfather of American graphic design. Rand believed that design should have ‘the utmost simplicity and restraint’, and he applied his modernist, European philosophy across his body of work for book publishing, advertising and branding, including logos as familiar and famed as IBM, ABC, UPS and Enron.

It was the next great influence on Bernbach’s career, not just Rand hinself but the fact that they worked together. At Weintraub, the separation between copywriter and art director was not as rigidly applied as elsewhere. The two men, just three years apart in age, were free to create in tandem, working on ads from the start of the assignment with no primacy of writer over art director. Their collaboration developed over free-flowing conversations that included lunches and roaming round galleries, all informing and illuminating Bernbach’s development as a communicator.

To Bernbach, this fusion of writer and art director became so natural as to be unquestionably the only way for creative people to work and for advertising ideas to be developed. It was the only way of producing complete ideas that are born from thinking of the way that words can most effectively combine with, and compliment, pictures.

His stay at Weintraub and his relationship with Rand was upended in 1941 by Pearl Harbour. Bernbach spent just two months in the Army, a pulse rate of up to 148 making him unfit for duty. He came back to New York and after a short stint as Director of Post-war Planning at Coty Inc, the cosmetics marketer, rejoined advertising at Grey. Like Weintraub, Grey was a ‘Seventh Avenue’ agency, a predominantly Jewish firm. The sobriquet derived from so much of the garment business – traditionally the client base of Jewish agencies – being located on Seventh Avenue.

By 1945 Bernbach was copy chief, familiar to clients and agency management alike and clearly hitting his stride. But he didn’t like the way things were run at Grey, a regimented, unprogressive place with little imagination or room for creativity. And within two years he’d written his famous letter.

But at Grey, his letter and his views were ignored; the agency’s Board was happy with the way things were, and didn’t want his troubling new ideas on management structures and company philosophy.

Amongst the Grey client roster was a budget department store that sold mainly women’s apparel and accessories. This was Ohrbach’s – ‘A business in millions, a profit in pennies’ – and Bernbach had worked on the account personally, again in direct collaboration with an art director he’d hired, Bob Gage. Their work had caught the eye of Nathan Ohrbach, the owner, and he urged Bernbach to leave and set up his own business with the store as his first client. Initially Bernbach demurred, but when a few months later Ohrbach came back and said he was pulling the business out of Grey anyway, Bernbach took the plunge and started his own agency.

NED DOYLE, then a Grey account director, was at face value a curious choice of partner. He was ten years older than Bernbach, a fighting Irish ex-marine, physically imposing, with an active service record in the Pacific and almost a parody of the type; hard smoking, hard drinking and hard swearing. Bernbach was soft spoken, quietly mannered, 5 foot 7, nonsmoking, abstemious with alcohol and unremarkable to look at.

When he first met Bernbach, Doyle described him as a ‘nice little guy, very creative with gold-rimmed glasses, and on the scared side’. But then, perhaps most people he met for the first time appeared to be a little on the scared side – they probably were. This is Doyle several years later on the phone to the DDB Los Angeles office chief, giving him advice on handling his client Ernest Gallo who was making trouble: ‘You go to a store and buy a power mower. Put it in your car and drive to the winery. When you get there, shove it up his ass and turn on the power.’

Even Roger Sterling would have been impressed.

That Bernbach could ever conceive such an idea, let alone speak it out loud, was quite unthinkable. Yet the two hit it off to such a degree that they were happy to risk it all and hang up their shingle together. To Bernbach’s start up philosophy can be added Doyle’s; as Doris Willens writes, he wanted to create an agency ‘whose principles we could believe in… To give [the client] the work we think he should have, provided it fit his goal… Not to wonder what the client’s wife is going to say about the advertising.’

No ketchup with their sea bass then.

Doyle had a friend, Maxwell ‘Mac’ Dane, who already ran a small agency at 350 Madison Avenue with walk up offices – the elevator stopped at the floor below and you had to climb the stairs to the remaining floor. So with premises, a few staff, lines of credit, a little seed money from the partners (Bernbach put in $1,200) and a generous goodwill advance on fees from Nathaniel Ohrbach, the business was off and running.

‘I have no rules for people. I just want them to do what comes naturally to them, but to do it in an effective way. So that they’re doing their own thing, but they’re doing it in a sharp and disciplined way to make it work.’

BILL BERNBACH

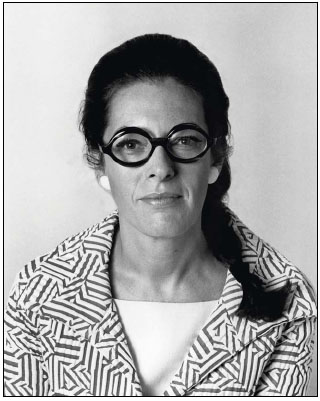

Bernbach took two key creative people: Bob Gage as Head Art Director, and Phyllis Robinson as Copy Chief, the only writer. ‘A Copy Chief of me’, as she later said. Gage and Robinson endorsed Bernbach’s philosophy. As Gage later said in DDB News, ‘The combination of the visual and the words, coming together and forming a third bigger thing, is really fundamental.’ Robinson added, ‘The whole being greater than the sum of its parts – this was something very new. It seems astonishing to think about it now because it seems like the most natural thing in the world.’

PHYLLIS ROBINSON was born in 1921 and brought up in New York. Attracted to advertising as a child, she even told her high school teacher that that was the world she wanted to work in, a wildly eccentric notion for a young girl at that time. She remembers being fascinated by ads, taking particular delight in the Burma Shave billboards along the highways. Each told a sequential part of a story in verse and as you sped by, the tale unfolded, billboard by billboard.

But in her late teens, she had ‘developed a little political and social awareness – things were falling apart in Europe and I had the feeling I should do something a little more serious’, so she chose to study sociology at Barnard College in Manhattan. She graduated in 1942 and, true to her ideals, started in public housing. But the war was to change everything.

‘My husband was drafted, pulled out of Harvard, and I tried to get public housing jobs, or something related to it, as I followed him around on his southern tour. But I couldn’t so I just got work wherever I could. At that point I was beginning to get back to the idea of some kind of writing, advertising or promotion.’

Robinson’s first agency job was with a Boston agency, Bresnick & Solomon B&S, while her husband, a future psychologist, was back at college. Then they moved to New York and she started at Grey, writing fashion promotions, where she caught Bernbach’s eye: ‘I worked directly under him and he did a lot… to tighten up my writing and make it more vivid.’ Eventually, he thought enough of her, early as it was in her career, to ask her to join him in his new venture. She didn’t need to think twice.

As lucky breaks go, they don’t come much more propitious. There was no way for her to know it at the time – this was, after all, just another risky little breakaway with no reason to imagine the success to come – but that one conversation was to propel Robinson into the very highest plane of New York advertising history.

Although her decisions were usually subject to Bernbach’s ultimate sanction, she had enormous influence over the conduct and development of the agency’s creative output. It was she who for the next decade or so approved work and employed writers, combing their books for indications that here was a talent that would fit with DDB’s strange new attitudes. Don’t forget, there was little training ground for DDB – no college or rival agency was turning out writers practised in its way of thinking and working. It was too new. Any writer hopeful of getting work there had to be either studying their methods and attempting to reproduce them in their own time, or osmotically producing work in DDB’s style for their current agency, almost inevitably doomed to be rejected by their own management but hopefully appreciated in an interview with Mrs Robinson.

In those early years she hired more women than men, observing with either undue modesty or remarkable candour that it was perhaps because she felt easier being a boss to women. Judy Protas was her first hiring, from the advertising department of Macy’s. Paula Green was hired with a background of writing for magazines and agencies, including work in account service. Lore Parker, an Englishwoman born in Germany with no copywriting experience, got her job purely on the strength of a letter she sent in to DDB. Later she would say, ‘The most successful headline I ever wrote was “Dear Mrs Robinson”’.

Protas, describing the office in her very first days at the agency says, ‘We were squeezed into the penthouse and Ned Doyle looked at me and said, “Kid, can you work hanging from the chandeliers?”’

Phyllis Robinson; DDB’s first copy chief.

BOB GAGE, Robinson’s opposite number as Head Art Director, had been hired a few years earlier by Bernbach at Grey. He was yet another hopeful who had nervously removed pieces of work from his folio the night before his interview. Gage was worried that Bernbach would not be impressed merely because they’d been published, and replaced them with speculative work of his own. The meeting went well, discussing their own views of advertising and finding much common ground – ‘I had at last found someone who not just tolerated new ideas but demanded them’ – and he was hired. Gage, too, had been influenced by the spare style of Paul Rand and an even bigger influence was Alex Brodovitch, art director of the radical Harper’s Bazaar magazine.

Brodovitch’s was an extraordinary story; a Russian émigré who had lived the prototypical bohemian life in pre-war Montparnasse where he had immersed himself in just about every possible artistic movement in the dizzyingly evolving scene around him. That hectic artistic development was manifest in his obsession with never doing the same thing twice, an utter abhorrence of the unoriginal. Art Kane, for a time the unparalleled fashion and music artist photographer, said, ‘He taught me to be intolerant of mediocrity. He taught me to worship the unknown.’ Hiro, the fashion photographer, echoed, ‘I learned from him that if, when you look in your camera, you see an image you have ever seen before, don’t click the shutter.’

Gage, too, carried into DDB this almost neurotic desire to be fresh every time, exactly in accord with what Bernbach wanted. But he had two more qualities to add to the mix that marked out his work. One was extreme self-effacement; when asked to supply a biography for an award from the New York Art Directors’ Club many years later, he wrote merely: ‘Bob Gage, Vice President and Head Art Director of Doyle Dane Bernbach since the day it opened its doors’. In a business noted for noisy egos and monstrous self-satisfaction, this was almost bashful; such quiet modesty meant he was incapable of producing the loud, chest-beating advertising work of a Rosser Reeves.

Gage’s other quality was that he was simply a thoroughly good man. In a particularly crucial quote, from the Art Directors Hall of Fame, about the criteria for employment at DDB, a quote that tells us not just about Gage, but also about Bernbach and the whole ethos of the agency, Bernbach said, ‘You have to be nice and you have to be talented. If you’re nice, but untalented, we don’t need you. If you’re talented, but a bastard, we don’t need you. No one exemplifies the nice and the talented better than Bob Gage.’

As Gage said, the agency’s creative solutions were derived directly from cold facts about the product itself. But that was just the start. His achievement, initially with Robinson and Bernbach and then with a succession of later DDB writers, was in warming and moulding those ‘cold facts’ into a body of work of genuine warmth and emotion. The simple humane charm in the stream of work moved reader after reader, viewer after viewer with an emotional impact transcending anything necessary for the purely utilitarian purpose of advertising.

The sheer vivacity and freshness in the work they started to produce reflected the childlike euphoria in the first few years of the agency. Phyllis Robinson later said, ‘We all had, including Bill, the feeling that we were let out of school – you know, no more teachers, no more books… a tremendous feeling of freedom, just for starters.’

Behind every famous campaign there’s usually an open-minded client, deserving recognition at least for judgment, taste and, quite often, bravery. The easy, comfortable solution is to do what you’ve done before, what everyone else is doing; the far-sighted client knows this is the worst solution. Nathan Ohrbach was one such client.

Encouraging and applauding his advertising teams to come up with fresh and original thinking, it showed in his choice of agency; he’d employed Weintraub in the mid forties, then moved the account to Grey when Bernbach started doing interesting work there. Finally, like a commercial Medici, he encouraged and backed the breakaway. It paid off. His business grew, enabling expansion into suburban New York, Newark, Los Angeles and elsewhere.

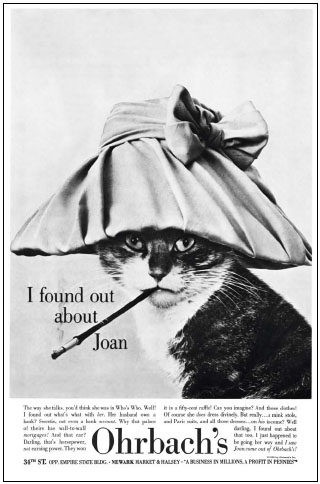

OHRBACH’S ADVERTISING already had some fame around town as one of the more noticeable and radical pieces of retail work, and this was boosted early in the agency’s life by the ad that one could argue marked the start of the Creative Revolution. To today’s sensibilities it may seem patronising and condescending, but those were different times and it gained attention through its very playfulness.

Ohrbach’s advertising created by DDB in the late 1950s.

A man is carrying a grinning woman under his arm, flat like a cardboard cutout, with the headline ‘Liberal Trade-in. Bring in your wife and just a few dollars… and we’ll give you a new woman’.

The idea was Bernbach’s – described by Gage as ‘the most visual copywriter I ever worked with’ – but the copy was left to Phyllis Robinson to write. (Bill was now mostly concerned with ideas and headlines, others could do the ‘wiggly bits’, the actual body copy.)

The message of the ad is loud and clear: new fashionable clothes a complete makeover at bargain prices. But the novelty was in the way it was said, a key DDB attribute, playing with the notion of advertising by borrowing language from elsewhere – auto sales for example – and applying it here to your wife. Intriguing and entertaining the reader, but all the while selling.

In the same year, 1952, the headline ‘If you are over or under 35… you need SNIAGRAB (spell it backwards)’, over a picture of a white-coated man pointing straight at you, spoofed another style of advertising, this time pharmaceutical. But the idea was not so much satirising other ads as having fun with the whole notion of buying and selling and advertising, a conspiratorial wink between seller and buyer.

A few years later, in 1959, they produced another startling ad, in which a cat wearing a fashionable hat and smoking a cigarette in a cigarette holder makes catty remarks about a friend behind her back, revealing that she isn’t as wealthy as she seems – she achieves the illusion by, shocking to reveal, shopping at Ohrbach’s!

Ohrbach’s was like a client magnet for DDB. Other New York businesses looking for an agency would ask around to find who did the advertising and then approach DDB to handle their account. In fact, in the following decade DDB rarely, if ever, made a formal new business presentation, as often as not being approached by clients rather than the other way round.

ONE INTERESTED ENQUIRY came from Whitey Rubin, put in charge of a small Jewish bakery in Brooklyn by its bank in a last-ditch attempt to turn the business around and keep it from bankruptcy. For 30 years they had traded successfully selling bagels, onion rolls and challahs to an almost exclusively Jewish clientele. The problem arose when the company extended its range to a variety of breads baked to appeal to a wider market. The Jews didn’t like it and the gentiles didn’t know about it. Quoted in Robert Glatzer’s The New Advertising, on his first sampling of the new breads Bernbach said, ‘Mr Rubin, no Jew would eat your bread. If you want more business, we have to advertise to the goyim [non-Jews].’

So the initial original thought by DDB for Levy’s was a media idea, concentrating exclusively on a specific market. Next, they contradicted the received wisdom that good bread must be soft, and they began to promote the nourishing values of Levy’s Oven Krust White Bread with a series of intelligently but simply-argued ads. One asked ‘Are you buying a bread or a bed’ and another, against a drawing of a fat child contrasting with an athletic child, ‘Is his bread a filler-upper or a builder-upper?’ This was good hard-working stuff, and a slow improvement in sales followed.

Then Phyllis Robinson wrote a radio campaign around a small boy whose mother continually tried to correct his faulty pronunciation of ‘Wevy’s Cimmimum Waisin Bwead’. His pay-off line, ‘I wuv Wevy’s’, became a catchphrase, boosting Levy’s name recognition and fame. But the taste of things to come was an ambitious claim, with a simple layout graphically illustrating the thought: over three pictures of the same piece of rye bread, quickly disappearing as bites are taken out of it, were the words ‘New York… is eating… it up!’

New York certainly started nibbling. It was advertised as ‘Levy’s real Jewish Rye’, itself a little contrived as there’s nothing particularly Jewish about rye bread. And Rubin, anxious about anti-Semitism, couldn’t initially understand why its Jewish provenance needed to be flagged up at all. ‘For God’s sake’, countered Bernbach, ‘your name is Levy’s. They’re not going to mistake you for a High Episcopalian.’

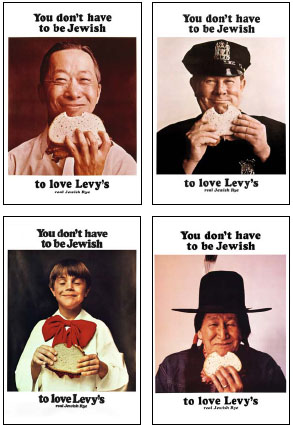

In the increasingly worldly and sophisticated market that New York had become, maybe that touch of exoticism was exactly what the brand needed. What came next, created by writer Judy Protas and Bill Taubin, generally reckoned to be one of the very best of DDB’s earlier art directors, reinforced and amplified that exoticism. In one large picture and one simple line they linked one minority – the Jews – to all the other emerging minorities making their presence felt.

Subway passengers became aware of posters with large, engaging pictures of the people you’d least expect chewing through a hunk of Levy’s. And if they looked authentic, that’s because they were authentic. Howard Zieff, the photographer, who went on to direct some of the very best commercials of the sixties before starting a new career as a Hollywood director recalls, ‘We wanted normal-looking people, not blonde, perfectly proportioned models. I saw the Indian on the street; he was an engineer for the New York Central. The Chinese guy worked in a restaurant near my midtown Manhattan office. And the kid we found in Harlem. They all had great faces, interesting faces, expressive faces.’

It would be easy now to dismiss the whole campaign as stereotypical, even condescending, but not then – far from it. These ads were startling for the simple reason that such people weren’t usually seen starring in advertising. New Yorkers revelled in it, demanding copies of the Levy’s posters as well as the bread. It reflected and celebrated their contemporary multi-culturalism, and for the immigrants it helped ‘normalise’ their status simply by making them seem an accepted, normal part of society.

It is a wonderfully simple idea, little more than the strategy, photographed. Yet within it you can find all the unique hallmarks of a DDB campaign: wit, surprise, freshness, fun, simplicity, directness, a credible promise – and again that knowing but friendly nod and wink towards the consumer.

THIS, IN ESSENCE, was what was so different about DDB. The new graphics, the design, the choice of typefaces, the style of copy – all are fascinating in their own right, but in the end they’re not the answer, just part of the means to the end. What these ads were doing was signalling a changed relationship between those who would sell and those who would buy. A relationship based not just on respect for the people’s taste but for their intelligence and ability to discern what really mattered in their lives from the purely transitory.

To a client, his product is life and death, something that if only the wilful public would try, they’d realise would change the course of their lives; but to a busy housewife or commuter, it’s often no more than an irksome purchase on the way to something else. DDB had the honesty to recognise this, and the candour and skill to communicate that recognition, making the potential buyer an ally rather than a target. ‘The artist rules the audience by turning them into accomplices’, as Arthur Koestler put it.

1964–5, DDB’s ‘You don’t have to be Jewish…’ campaign for Levy’s, a huge commercial and cultural success.

Bill Bernbach’s people, without impudence but based on self-respect and a belief in their ability to communicate properly with the public, ended the slavish deference towards the client and the product. Bernbach recalled a conversation with a new business prospect: ‘“What would you say, Bill, if you were told exactly where to put the logo and what size it would be [on the advertisement]?” I had $10 million riding on my answer and I said, “I would say we’re the wrong agency for you”.’

It wasn’t a question of either Reeves’ hard sell or Ogilvy’s respectful but rule-based formulaic sell. It took the best of both and shucked off the remains. As Bob Gage had observed, no DDB ad would ever be created without a rigid consumer proposition at its centre, the philosophy at the heart of Reeves’ USP idea. And no DDB ad would ever be created without deep respect, not just for the consumer’s intelligence, but also the consumer’s true priorities. Bill Bernbach stopped selling dreams and started selling the truth – wrapped in wit.