‘Have we ever hired any Jews?’ ‘Not on my watch… we’ve got an Italian.’

ROGER STERLING AND DON DRAPER MAD MEN

The clients, big and small, national and local, flocked in. All were taken on DDB’s terms, which included a tacit ethical standard; the product must be honest and worthy of the money that the agency would be asking the public to pay for it.

Jim Raniere, an art director who joined DDB in 1961, contrasts the ethos at DDB with agencies that friends had joined: ‘Never lie, never never say anything about a product that it can’t do’.

The account for The Book of Knowledge, a children’s encyclopedia, came and then went when a new copywriter found it was too complicated for his eight-year-old daughter. On those grounds he refused to work on it. The rumpus was elevated to Bernbach who took the book home with him. The next morning he pronounced that the product was flawed and the client was told the agency no longer wanted to advertise it.

High-minded, yes. It wasn’t just posturing, it was in reaction to the generally bad name that advertising had around town. And it was driven by the new breed of people that Bernbach and his managers were employing, people of a completely different stock with a completely different mindset.

Up until the late 1950s, advertising had been seen by account people mainly as an alternative to Wall Street, with good salaries at a fairly early age and a respectable life dealing with upper levels of client companies in an influential milieu. Copywriters, too, tended to be from comfortably educated backgrounds. You might get the odd Italian as a visualiser but who cared? The client never knew who he was, let alone got to meet him. In the late 1950s, Jerry Della Femina, a young copywriter, was told in an interview at JWT that on the basis of his name alone, Ford Trucks ‘wouldn’t want your kind on their account’.

But beneath the well-shined Oxfords of the comfortable WASP account executives patrolling the Madison Avenue sidewalks, the world was turning and several elements were beginning to coincide to make the Creative Revolution almost inevitable.

AS ITALIAN-AMERICANS like Della Femina were demonstrating, there was a growing confidence among the second and third generation ethnics, people born from the mid 1930s onward. Their Ellis Island parents and grandparents, perhaps cowed from the oppressive experiences in the Europe from which they had escaped, were desperate to conform, to assimilate and become American. Deference was their watchword, but as familiarity and security came, so too did self-assurance, and this new generation no longer ‘knew their place’.

Very few had any reservations about applying for white collar jobs in advertising agencies, an aspiration that probably would never have occurred to their parents. Although there were the occasional setbacks, increasingly foreign names were appearing on doors along the agency corridors, and ethnic origins were a matter of pride.

George Lois remembers his interview with Lou Dorfsman at CBS Radio in the fifties; Dorfsman, son of Polish Jews, rolled George’s name around his mouth and said, ‘Lois, Lois – is that a Jewish name?’

‘I’m not a fucking Jew’, countered Lois, ‘I’m a fucking Greek!’

A key Bernbach remark, ‘You always have to work in the idiom of the times in which you live’ could be applied to the people most appropriate to produce that advertising. This group of creative people had none of the cultural inheritance of the older guard, the pre-war New York. And they certainly didn’t respect the creative legacy of the existing inhabitants of the agencies; quite the reverse. They felt alienated and appalled by it, responsible as it was for so much of the general antipathy towards advertising. It was neither their language nor their imagery. And one word above all others crops up over and over again, with deep disdain, in the contemporary interviews and records of their views.

Phony.

It was the one thing they did not want to be, and the one thing they resented above all others about the current advertising. Commercials with actors playing reassuring doctors; perfectly coiffed housewives trilling about the perfection of their cake mix; and men in white lab coats holding up test tubes and booming in authoritative voices some drivel about ‘ingredient X’.

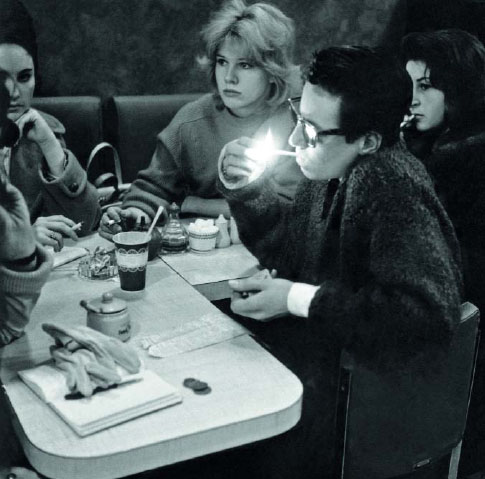

IT WASN’T JUST THEIR ORIGINS, it was also their youth. America had just invented the teenager, had begun to give these youths presence and influence, and they were the first to benefit. Rebellion was in the air, with the icons of James Dean and Marlon Brando to emulate. There was even, for the more anguished, Holden Caulfield, JD Salinger’s young, disaffected hero from Catcher in the Rye.

‘We came home full of kick-ass energy and the GI Bill to educate us. Tradition, school ties and old boys clubs became relics’, said Jim Durfee, a war veteran. At the time, he was a copywriter at JWT in Detroit, but later he was to co-found Carl Ally Inc, one of the very best agencies of the decade. That energy found a period of literally fantastic artistic expansion and experimentation to feed and fuel it. As George Lois wrote in a 2010 Playboy article, ‘It was an inspiring time to be an art director like me with a rage to communicate, to blaze trails, to create icon rather than con. The times they were a-changin’.

From the white-tie audiences at Carnegie Hall to the marijuana-clouded coffee shops of the beat poets on Bleeker Street, the black be-bop jazz clubs of Harlem to the cooperative galleries of Tenth Street, nothing stood still.

With Manhattan’s frenetic building and rebuilding programme, the world’s leading architects added their prestigious signatures to the cityscape. In 1959, Frank Lloyd Wright’s futuristic Guggenheim Museum was finished one year after Mies van de Rohe’s beautiful Seagram Building, fifty-two sheer stories sheathed in bronze and bronzed glass, the classic functionalist skyscraper. In furniture, European influences from the Bauhaus onwards removed the stuffing and streamlined the design – by the 1960s no agency with any self-respect could have anything other than Charles Eames chairs in their reception area.

The spread of the 35mm camera, with its changeable lenses and greater portability brought magazines an indispensability and urgency as exciting news vehicles. Until television usurped it in the late 1950s, Life magazine had its purple period, sponsoring not just dramatic photography but superb illustration; its lofty literary content included the first publication of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea.

IN MUSIC, ART AND LITERATURE a dazzling explosion of imagination and energy fired a million incandescent ideas across the decade, some false and quickly sputtering, others arcing with a brilliance into the next century. But it was ignited against a social background that was far from settled.

Jazz writer Jeff Fitzgerald describes jazz in the 1950s as taking on ‘a restlessness, reflecting an undercurrent of trepidation lying just beneath the surface. Jazz became more cerebral, more introspective… the music of a generation in transition, searching for its identity in a world populated by increasingly invisible, intangible perils. In a world living under the shadow of the atomic bomb and the creeping menace of Communism and an increasingly automated society feeling the control of its own daily existence slipping away with the push of every button, it is perfectly logical that the music should reflect that nameless angst’.

He could have added the tension caused by the rapidly growing awareness of racial injustice, and it was the black population that was the driving force behind jazz. Musicians like Art Blakey, Charles Mingus and Thelonious Monk took the music into infinitely more complex forms. Free jazz ‘experiments’ were taking place at the Five Spot on Cooper Square, organised by musicians like Ornette Colman.

More accessible were the Modern Jazz Quartet, Dave Brubeck and Lester Young. But perhaps the best evocation of the jazz of the era, hypnotising the hip crowd at Birdland and the Village Vanguard, was the poignant foggy moan from the trumpet of Miles Davis, the man Kenneth Tynan called ‘a musical lonely hearts club’.

It could hardly have been in greater contrast to that other massive trend in music; in 1954 Bill Haley and the Comets released ‘Rock Around the Clock’ and the dance hall, the record player and the juke box would never be the same again.

The visual and performing arts were even more explosive. Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and friends in the New York School threw paint around in an excitable way never seen before, creating the genre known as Action Painting. Meanwhile, for a very different audience, Mark Rothko was commissioned to paint a set of murals for the opulent new Four Seasons restaurant.

Between Tenth and Twelfth Street, in reaction to the stultifying and exclusive establishments of Fifty-seventh Street and Madison Avenue, artist-owned galleries gave an outlet to every experimental idea. Artists like Jim Dine and Claes Oldenburg were collaborating with poets and musicians such as John Cale in the phenomena of the Happening, a partially free-form, audience-participation performance art (which gave rise to a misplaced lingerie ad of the time, a woman floating in space with the headline ‘I dreamt I was at a Happening in my Maidenform bra’).

And in the mid 1950s an art director at Benton & Bowles asked the name of the hopeful blonde female illustrator who’d just shown her folio to a colleague in the office next to his. ‘That wasn’t a chick,’ he laughed, ‘I’ve got his name somewhere… er… Andy Warhol.’

In the Village book shops and coffee houses, jazz/poetry fusions were achingly hip. Jack Kerouac appeared with a jazz group at the Village Vanguard on Seventh Avenue in 1958 and recorded readings of his prose and poetry with the saxophonists Al Cohn and Zoot Sims. Free-form impromptu poetry readings – one notably earnest performance was a reading of the Manhattan telephone directory – were a regular, if often meretricious, stimulus for impressionable young minds.

From the early 1950s, Washington Square had been the focus for the emerging folk scene, with groups and individual folk singers gathering for impromptu open-air sessions. Thriving, it spread to specific clubs and by 24 January 1961, fresh from the Midwest, the 19-year-old Bob Dylan knew enough to head for the Café Wha? at 115 MacDougall Street. He blew in, snow on his coat, and asked to perform a few Woody Guthrie songs. It was his first appearance in the city.

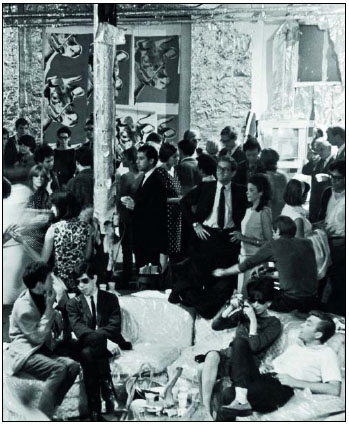

A party at Andy Warhol’s studio, The Factory (231 East 47th Street), New York, August 1965

At the Gaslight Club, a ‘basket house’ (so-named because the artists’ remuneration was the cash in the basket passed round amongst the patrons), Allen Ginsberg recited ‘Howl’, his terrifyingly powerful evisceration of everything he felt America had become. Earlier, in the same club, Jack Kerouac had read from On the Road.

Cinemas were showing Rebel Without a Cause and On the Waterfront, dramatising youthful angst and alienation, while The Seventh Seal and Seven Samurai intrigued audiences with a growing appetite for foreign directors with a completely different feel for film. At the theatre, Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night and Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman all penetrated themes embedded deep within society – and all won Pulitzer prizes.

As for literature, you took your pick from books, essays or poems from William Faulkner, Henry Miller, Ayn Rand, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, James Baldwin, Richard Yates, John Cheever, Isaac Asimov, Saul Bellow, Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, John Updike… the list goes on.

This was the background to the formative years of this new generation of creative people. Whether they immersed themselves in all, part or none of it is not really the point; the fact is that this was their seedbed, seeping osmotically into all creative endeavour. It couldn’t but help inform and illuminate their work.

BY 1960, JWT had doubled their 1950 billing to $250 million, retaining the number one spot. Their growth neatly reflected the decade’s overall doubling of national advertising spend, up from $5.7 billion to $11.96 billion, evidence of the boom in business accelerated by the growth of TV advertising. But DDB had spectacularly outstripped the market with a hundredfold increase, taking them from $500,000 in 1949 to $46.3 million ten years later. A creditable client list of all product types and sizes (although they still lacked a major packaged goods client), from Coffee of Colombia to Rheingold Breweries, Philip Morris Alpine Cigarettes to Max Factor, Chemstrand to Clairol, defined an agency that was now firmly grounded. And a succession of campaigns began to demand that their competitors take them seriously.

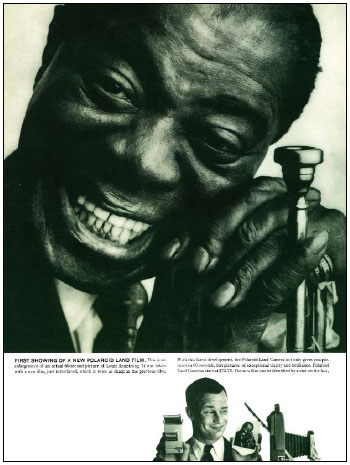

For Polaroid, the first camera to produce a print within 60 seconds of the picture being taken, DDB produced several campaigns, each as radical as any advertising the public had ever seen. The previous agency, BBDO, had completely missed the point and produced messy, uninspiring work based on a mishmash of propositions, including price, which served only to make the product look a cheap gimmick.

On taking over the account in 1954, DDB zeroed in on the product benefit with a ‘live’ TV campaign that appeared on Steve Allen’s The Tonight Show. During the transmission Allen would take a picture on stage, maybe walking into the stalls to snap a member of the audience, and then talk about the camera while the picture developed. Showing the print to the audience was like the climax and reveal of a conjuring trick, always eliciting applause. How simple, direct and desirable, to have an unsolicited live TV audience applaud your product on national TV.

Then, in 1957, Polaroid introduced a highly sensitive black and white film, and again dramatic simplicity did the trick. The art director, Helmut Krone, hired fashion photographer Bert Stern to take tight close-up pictures of characterful faces, some known and some anonymous. In full-page ads, these dominated the page: every pore, every line, every shadow clear and faithful. Simple copy by Bill Casey told you all you needed to know with the minimum of fuss. There’s seldom been a better example of letting a good product sell itself.

ANOTHER TREND in DDB’s work started to become noticeable. In contrast to the rigid laws on the use of space laid down by Ogilvy, DDB art directors were quite prepared to play with the imagery, with the page itself, to make the point visually. If advertising had always been regarded as sales talk in print, DDB was frequently doing demonstration in print.

To dramatise Flexalum dirt-resistant window blinds, Bernbach suggested a picture of a tennis ball bouncing off the slats. In another campaign, Helmut Krone showed a photo of a gift-wrapped package in a thin vertical space up the side of a page of Life magazine. When the reader held the page up to the light, as invited ‘for an X-ray peek at a great gift’, they saw a bottle of Ancient Age (‘If you can find a better bourbon, buy it’), apparently on the inside. It was illustrated on the reverse side of the page and showed through in the light.

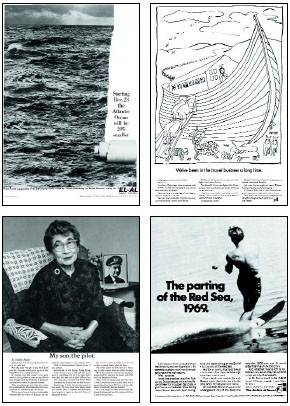

1958 DDB ads for Polaroid, featuring Salvador Dalí and Louis Armstrong. Instant picture, instant success.

You got the point at one glance in one of DDB’s greatest-ever ads, opposite, when Bill Taubin tore a strip off a picture of the sea to advertise a new faster service from New York to Tel Aviv for El Al Airlines. The way the ad worked on the eye was the demonstration itself. El Al’s budget was relatively small, a fraction of that of even most domestic airlines and DDB could have imitated the approach of all other carriers, using little more than flight schedules printed on the page, with no attempt at any personality. But with El Al, they went further than just new visual ideas – there was a new verbal excursion as well.

El Al was one of Bernbach’s many Jewish accounts. While it wasn’t remarkable that they should have so many, what was remarkable was the way they handled their Jewishness. Far from hiding it, as Whitey Rubin of Levy’s had been inclined to do, DDB celebrated it, and wrote their ads in Borscht Belt idiom. A full page advert with a picture of Noah’s Ark made the point: ‘We’ve been in the travel business a long time’, a terrific example of how words can take off from the picture to make a further point.

While the Italians were infiltrating the art department, it’s difficult to overemphasise the role the Jewish writer and Jewish idiom played in the Creative Revolution. If you look at the roster of the artists, architects, designers, musicians and particularly writers who were illuminating the fifties, you’ll see an extraordinary percentage of Jews. It had its effect; the Yiddish vernacular and Jewish humour were creeping into the New Yorkers’ daily language. Few advertising agencies, dominated as they were by pallid WASP values or an incipient Anglophilia, had seemed to notice it, but as DDB’s doors were open to the immigrant and the Jew, the people who lived and breathed these things, it was only natural that it would end up in their work.

SO ON THE VERY VERGE of the 1960s, from many and varied directions, apparently unrelated circumstances converge. We can connect them. In the world’s greatest modern city, a massive economic expansion creates a huge need for the raw product of the advertising business, the ads themselves. The audience for this outburst is a demographically younger, newly wealthy and curious American, on the edge of a consumer boom – and thoroughly tired of the advertising it’s been fed. A brand new medium is sweeping the country and revolutionising advertising practice, bringing with it opportunity and the chance to experiment.

Understanding the market and the idioms, the El Al Airlines ad campaign, from 1958 to 1970, was among DDB’s very best work.

The doors of a few agencies are being opened to a completely new breed of creative person, one who sees no value in looking back, and who demands to do things in a radically new way. The images and references that will influence their work crackle around in their heads, fizzing from one of the greatest cultural eruptions the world has seen.

In one agency, DDB, those same people are given greater autonomy and prestige, and a new way of working together, which not only overturns the nature of their output but doubles their influence within the business. This financially successful, creatively-led agency is no unproven flash in the pan; for ten years now it has been proving that research does not know everything and, as Bernbach recognised publicly, cannot be used to come up with ideas. That, as his agency had slowly been proving, is the job of these new creative people.

As these circumstances converged, intertwined, coalesced and reformed, it was time for those creative people to take control.