“They did one last year, the same kind of smirk. Remember, Think Small. It was a half-page ad on a full-page buy. You could barely see the product.”

HARRY CRANE MAD MEN

The most famous part of the most famous campaign was born out of accident and confusion. At least half of the creative team who conceived it had doubts—and if it hadn’t been for the intervention of the client, one of the greatest ads ever written would never have been created.

The task was utterly daunting; to sell a small, basic, ugly, economical, foreign car to a market enthralled with huge, chrome-finned, gadget-stuffed, home-built gas guzzlers. Initially, a number of the people who worked on the Volkswagen (VW) account had misgivings. With the revelations of the full horrors of the Holocaust little more than a decade old, Bernbach, although clearly not bothered himself, had to make considerable effort to persuade his agency to take the account in the first place. As George Lois said, “We have to sell a Nazi car in a Jewish town.” Lois’ parents had emigrated to the US from central Greece before the war, and he was implacable in his opposition; tales of Axis behavior in Greece hadn’t endeared him to any idea of cooperation.

Additionally, the business was at DDB only as a sprat to catch a mackerel; one of Bernbach’s attempts at talking Lois around was to tell him, “We’ll take it for just a year and use it to get GM.” It’s probable he meant it too; it seems a perfectly reasonable business decision, if a little cynical. And it worked later in a different category—their much lauded campaign for El Al netted American Airlines in 1962.

Lois remained unpersuaded, but international events took a hand. He was sitting in his office one day: “It had those fogged glass windows and I could see Bill lurking outside. Then he opened the door a crack and stuck his head round the corner, like in The Shining—’Heeeere’s Johnny!’—and said, ‘Look at this’. Then he shoved a newspaper through the gap and held it up so I could read the headline; ‘Germany sells fighter jets to Israel’. He said ‘It’s alright, see?’ So eventually I agreed.”

Discontent rumbled on though. Lois remembers one prank when he made a small “flip” book with a VW logo on the bottom of the first right-hand page. As you flipped the pages, the legs and arms of the VW symbol quickly and neatly rearranged themselves—into a swastika.

He was showing it to a bunch of creative people when Bernbach walked by. “Hey Bill, Bill, hey, come here, have a look at this.”

Bernbach watched the little dance of digits, expressionless.

“Very funny George—now burn it.”

Lois went to work on the station wagon, the even less glamorous variant and only alternative to the basic “saloon.” “Basic” is the operative word for the then very alien VW.

THE BEETLE—although not referred to as such by VW until the late sixties—already had a toehold in the United States, thanks to US servicemen returning from Europe. It was originally designed by Ferdinand Porsche as the KdFWagen (Kraft durch Freude Wagen, literally “Strength through Joy Car”) in 1933, under the patronage of no less than Adolf Hitler. By September 1939 mass production had still not started, and then with the outbreak of hostilities across Europe, the VW Wolfsburg factory was converted to wartime vehicle production. It wasn’t until the war was over that the first models started to leave the plant, when the factory was restored to car manufacture under the management of two British army officers, Colonel Charles Radclyffe and Major Ivan Hirst, producing cars for the transportation of the occupying forces.

As a concept, it was a good one. The objective was a car designed to be uncomplicated, reliable, and inexpensive. It was to be within the reach of every German family, to enjoy the new freedom of the burgeoning autobahns of the 1930s. The engine was air-cooled, as simple as a contemporary motorcycle engine. Mounting it in the back avoided the need for a transmission and the hump of a transmission tunnel on the floor between the rear seats, which made the car even simpler. It also created more room inside a comparatively small cabin. The floor pan, chassis, and suspension were equally uncomplicated.

It was this idea—a cheap utilitarian European car conceived for the 1930s working man and then built to carry servicemen around a war-blitzed country—that had to be sold to a nation used to soft suspension, plush upholstery, and powerful engines. Glamorous it wasn’t. The potential for its success can be gauged from the reaction of Ford Motors, after it was offered the VW factory for free: “What we’re being offered here isn’t worth a damn!” Or British car executives, who could also have had the plant and designs for nothing: “The vehicle does not meet the fundamental technical requirement of a motorcar… it is quite unattractive to the average buyer.”

DDB had won the account from JM Mathes in 1958. VW’s modest sales throughout the fifties were perhaps partly still generated by word of mouth, by the personnel returning from Germany, where the United States Army remained a visible presence. And there was a nascent market for smaller, imported European cars; there were a few enlightened motorists who were beginning to see through the smoke and mirrors of Detroit’s annual model changes and built-in style obsolescence. In response, in 1959, Ford, Chrysler, and GM all decided to produce their own “compacts.” This burgeoning change in attitude, and the fact that most European cars performed poorly on America’s highways and freeways, built as they were for smaller roads and shorter distances, meant that VW’s market was now coming under threat.

So that year, Carl Hahn, who was in charge of VW in the United States, started to look for an advertising agency. He and Arthur Stanton, the New York area VW dealer, trawled up and down Madison Avenue, going to all the big agencies currently without a car account. Though the business was comparatively small, there was plenty of eager attention from the competing agencies.

Hahn hated the presentations, uniformly. Today he says, “It was the only disappointment I had about Americans… going up and down Madison Avenue. The content of the proposed ads was always the same, a beautiful house, very happy people in front, beautifully dressed—and a glamorous car. Even that in most cases was not photographed but illustrated… with a stupid caption. But [they] didn’t have [any] life. I had more and more presentations. I was desperate, I told Arthur this is just impossible, we need an agency that fits our product.”

It’s unclear why DDB were not on Stanton’s original pitch list as he was a fan of Ohrbach’s advertising and was already using the agency for his dealership advertisements. But eventually he suggested a visit and Hahn agreed. He gives a fascinating insight into the difference between the conventional agency presentations of the time and the infinitely more laid back and candid DDB approach. Other agencies, and some clients, regarded DDB’s refusal to prepare speculative work for a pitch as arrogant; DDB insisted it was honest. Until you really got to work on a client’s business, how could you possibly know enough to do the right work?

“I went to these primitive offices, no big conference room or hall, no ten vice presidents in blue suits with neckties and white shirts, and executive vice presidents and senior vice presidents; there was just a man sitting on his desk in a windowless room, called Bill Bernbach by name, and he showed me work he’d done for El Al and more.… I decided what to do: offered for the first six months an advertising budget of half a million or so, which he accepted.”

BERNBACH CHOSE HELMUT KRONE as art director and Julian Koenig as writer. Krone was a second generation German American who had once briefly owned a VW. Born in 1925, he is now enormously respected as one of the most influential art directors in US history, even though for thirty years—almost his entire working life—he worked only at DDB. He was fastidious and exacting in his work; he went to Germany several times to extract as much information as he could about the car. He believed that design in the service of a product should be indivisible from that product; the look and feel of the page, the attitude and body language of the artwork should reflect the attitude and body language of the product.

He also believed that including logos in ads was unimportant, a turn-off in fact, because as soon as a logo hits the retina it signals “advertisement” and thus becomes an invitation to turn the page. But that doesn’t mean he was undisciplined or careless with his clients’ problems; because of his belief in the indivisibility of “look” and “message” he would create for any client on whose account he worked a page layout that was instantly recognizable from twenty paces as uniquely theirs—even without their logo. It would also be a look that was universally applicable and workable; VW ads today, fifty years and literally millions of worldwide executions later, are still a recognizable reflection of his original template.

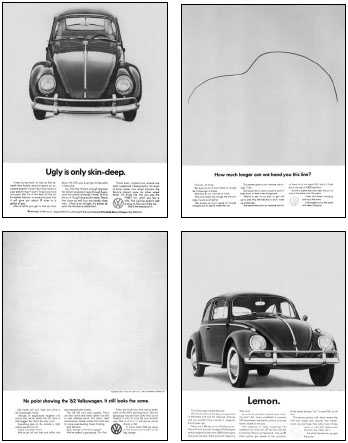

The layout for the VW campaign wasn’t particularly original, but it does perfectly exemplify Krone’s philosophy. In using a squared-up halftone photograph, a centered headline, and three columns of type, he was only sequestering what was then sarcastically known at DDB as the “Old JWT No. 1” or “The Ogilvy Layout,” referring to a lazily used hand-me-down layout found at agencies that were seen by DDB as creatively inferior. But the fact that it was well worn didn’t deter Krone; the car was simple and uncluttered, and its pitch to the customer was direct and honest. Look at the ads on the following pages, right down to the choice of typeface—how else to describe their appearance other than uncluttered and honest?

WHERE KRONE DEPARTED dramatically from the JWT/Ogilvy template was by taking this stripped down approach through to the photography. It was unheard of back then for almost any product, let alone a car, to appear naked of props, be they crunchy gravel settings in front of Connecticut country houses or doormen at plush Upper East Side apartments helping elegant women laden down with hat boxes. But the VW image was direct simplicity—so the ads also had to look simple and direct.

Krone was quiet, methodical, and unemotional. Some people found him difficult and moody. In Jack Dillon’s novel The Advertising Man, written while Dillon was still working at DDB as a copywriter, he describes the first morning for his central character, copywriter Jim Bower. He’s at his new “hot” agency, working with Brook Parker, the fictional Head of Art. After enduring a tense silence that goes on for nearly an hour while Parker sits stock-still, Bower tentatively suggests an idea for the ad they’re supposed to be working on. For several seconds there’s absolutely no reaction from Parker. Then, without shifting his gaze, he speaks: “We don’t do ads like that here.”

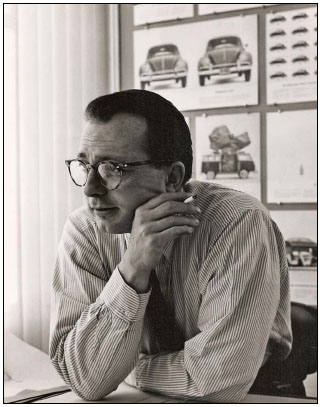

Helmut Krone; “a brooding kind of genius.”

Very Helmut Krone. As was Krone’s taciturn response to the novel, even though he hadn’t been positively identified: “I would never have called myself Brook Parker.” Krone had a fanatical attention to detail and shared Gage’s obsession with doing the original. Carl Fischer, a photographer Krone liked to work with, remembers a particular Polaroid shoot:

“On the first day the ad had to have ten children in it and we had carefully worked out all the ideas for the ten children. So we’re out on a beach somewhere near LA with a whole bunch of account people, a bunch of copy people, a bunch of clients… and ten children and ten mothers (and ten teachers which is required in California) and the food people in these catering trucks—it was a major operation. And we all knew what we were supposed to do… but Helmut decided it’s okay—but it should be better! So we stopped the shoot and sat down on the beach talking about how it could be better, as if all these people weren’t standing around waiting. Really it was a disaster but finally we came up with something and the client was happy. But the point is that Helmut suffered through everything he did. It had to be better, it had to be perfect, it had to be original, it had to be done the way nobody had ever done it before and that’s hard to do.”

Fischer liked him: “A lot of people said he was cold and remote and difficult to work with. I found him very easy… we got along very well.” Ted Shaine, a DDB art director describes him as “a brooding kind of genius, not very personable.” People put his remoteness down to a very tough childhood, apparently with a furiously strict father and, as he told Fischer, a mother who was a Nazi sympathizer.

“But he did have a sense of humor,” Fischer says, “it’s just it needed to be discovered. I first met him at a cocktail party. In those days I had a trapdoor above my studio and I used to take a lot of pictures from high up, looking down either at 45 degrees or straight down. And Helmut and I were introduced and he looked me up and down and said, ‘I expected you to be a lot taller.’”

JULIAN KOENIG, the writer, was the maverick type that often attracted Bernbach. Of comfortable birth into a family of lawyers, he nevertheless lived the life of the Bohemian nonconformist, at one time being part owner of a semiprofessional baseball team who played at a field in suburban Yonkers.

“This is just as TV was coming in to cover baseball and just as the color-line was fading in baseball because Jackie Robinson became the first black ball player back then—so we had a dream enterprise. It was semi-pro. We played good teams, a lot of whose players went to the majors. We had a big turnout on our first night, around six thousand people, but the city was viciously corrupt… never fulfilled their part of the bargain, which was to install toilet facilities. So you have the visions of women going under bushes and lifting their dresses. And once they do that they are never going to return.”

He became a copywriter in 1946 “for lack of anything else. I had written half a novel… which I sent to the Little Brown company, which was the firm that Norman Mailer had succeeded with. He had tried twenty-nine publishers, the thirtieth was Little Brown and they accepted The Naked and the Dead, so I figured I would skip the twenty-nine and go straight to Mailer’s publisher, and I was rejected. I became a copywriter out of lack of any other opportunity. I’d been at law school prior to all that and I wasn’t going back.”

Koenig’s first agency was tiny, with small accounts. “I was a junior copywriter or an apprentice copywriter. My office was in the file room… and you learn that if you can work there, you can work anywhere. It was good discipline. I was hired for $20.50 a week, which was less than the $25 I had been promised. So we organized the agency’s union, which I ended up leading. Then I left.”

By 1950 he was working and doing well at a bigger agency, Hirshon Garfield, but, in typical beatnik fashion, he suddenly gave it all up and traveled to Europe with his wife. It was an interesting time for a Jew to be in Germany. He remembers being at the beer festival in Munich, asking directions, and recalls with irony, “Nobody had ever heard of Dachau, which was ten minutes outside the city.”

They stayed for six months “until our money ran out… then I returned to Hirshon Garfield and was made copy chief and given a 50 percent increase in salary.” However, he had had very little work published so he took a leave of absence to work on a book. The “book” wasn’t of the literary type, it was for gambling on the horses. “I perfected my betting abilities. So I supported my wife and two children betting on the races. I had a horror of becoming the world’s oldest working copywriter. I could have continued at the track because I would have made more money than I would have working in advertising—but I got offered a job at the one agency I wanted to work at, which was Doyle Dane Bernbach.”

Koenig’s main claim to fame until then as a writer was a much-applauded campaign for Timex watches: “Takes a licking and keeps on ticking.” Amongst other “torture tests,” a Timex watch was immersed in the Dead Sea, put through a washing machine’s spin cycle, and even hosted by the digestive tract of a family pet. But this wasn’t the campaign that got him into DDB. He’d had a tip from Rita Seldon, a DDB writer he’d worked with previously, about a job going there. Bernbach looked through his book and, in the now regular pattern, hired him on the strength of an ad for a root beer that had been rejected by a previous client.

CARL HAHN HAD ALREADY written the VW strategy. It was the measure against which all the agencies he had visited had failed. He wanted everything about VW to be honest, transparent, and straightforward—the product, the pricing, the dealers, even down to the policy of changing the external appearance of the car as little as possible. This was in direct contrast with Detroit who deliberately made major design changes every year to make their cars obsolete and force an image-conscious public to continue forking out for the latest models.

It was therefore a simple matter for Ed Russell, the head account man, to write a strategy calling for honest advertising. The first line of the “Statement” as the strategy paper at DDB was called, was “The VW is an honest car.” Reading the body copy you immediately appreciate the candor with which Koenig approached the reader, very much following the strategy. In one way it’s Page One advertising copy, packed with product features and USPs. But it reads like a friendly chat—enthusiastic, yes, but more of a tip from one friend to another about something he or she ought to know.

“We just took [the] product and said what made it good. And we were fortunate that there was a lot to say about the VW.”

JULIAN KOENIG

What is more startling is the apparent challenge in the headlines, not just of the reader but of the product itself. They were all fundamentally negative, and that simply wasn’t done.

It’s impossible to imagine the jaw-dropping amazement with which Detroit executives and their advertising agencies must have viewed these ads from a rival car manufacturer, apparently advising their potential market that the car was a failure and of limited ambition. But it was all part of the same candor—tell ’em like it is and it’ll intrigue them and then amuse them. But don’t leave it there—while they’re busy appreciating you, gently insinuate some sales points.

THERE’S A CURIOUS STORY around the origination of the “Think Small” ad, one which enhances the already noble role of another bold and prescient client who would put his money behind such an unorthodox and, at that point, unproven and manifestly risky strategy.

The ad was originally meant to be a corporate ad, advertising the marque rather than a specific model, and it showed three huge American cars. Koenig wrote the headline “Think Small” to contrast with this visual. Then, as Koenig remembers it, “Helmut wouldn’t use it. And he who controls the [layout] pad in those days, controls the ad. So we finally come up with Willkommen, which I didn’t want but Helmut wanted, and with ‘Think Small’ in the copy. In DDB, copywriters and art directors didn’t go to the client with ads, the account people went. So they presented the ad, came back and said ‘Willkommen is out’. Fortuitously, Helmut Schmidt—the client—didn’t want Willkommen, which I knew they wouldn’t because that made it a German car, and we wanted to be as American as apple strudel, as the ad says. He saw the line ‘Think Small’ and thought that should be the ad.”

1959–60, early examples from the DDB campaign for VW.

So one of the most famous advertising headlines of all time was, if not exactly written by a client, certainly spotted and promoted by one. Koenig says, “I’m told in Germany they credit the ads to the copywriters Helmut Schmidt and Julian Koenig.”

According to Koenig, it took the famously grumpy Krone two days to bring himself to put the line down on paper. Meanwhile, the requirement had changed from a corporate to a product ad so it needed to show a VW. Initially, this further exasperated Krone by suggesting that logically, this meant the car should be shown small, which he didn’t want to do.

But he calmed down and, encouraged by Bob Gage and others around him, worked fastidiously at the layout. Eventually he placed a small car at a slight angle in the top left hand corner of the page—and an advertising icon was created.

THE CREDIT FOR “LEMON,” too, has a convoluted path. “The art directors used to put their advertising ideas up on the walls,” says Koenig, “and Helmut had put up my headline ‘This VW missed the boat’. Rita Seldon came into Helmut’s office and she said, ‘Lemon!’ Helmut said go tell Julian and she walked about thirty-five feet down to my office and said ‘Saw your ad, Lemon!’ I said, ‘Terrific’. So Lemon became the ad and I took my headline and made it into the first line of copy.”

This version is disputed by George Lois, who claims that Koenig wouldn’t listen to Seldon, and it took her two weeks to persuade him to make the change. But as the two have been, and still are, in a high-energy spat over who did what on all sorts of ads they worked on, some of which were created fifty years ago (with one of them even going to the extent of preparing an ad for The New York Times to “set the record straight”) it’s difficult to know who to believe. But it is to Koenig’s credit that he’ll cheerfully admit that the provenance of the world’s two most famous advertising headlines were not his and his alone.

The impact of the campaign was immediate, with the ads getting unusually high readership figures. Imported car sales at that time had halved in two years under the onslaught of the simultaneous launch of brand new compacts from all the major players in Detroit. But in the same period, VW sales actually rose by nearly 25 percent.

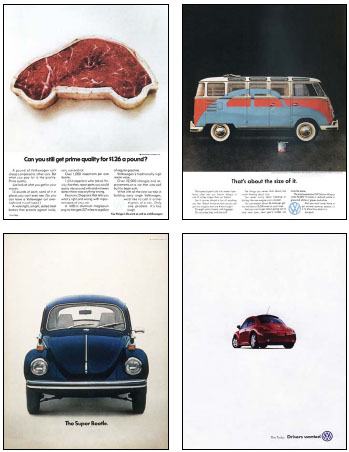

Reinforced by this obvious endorsement from the only meaningful measure, the marketplace, DDB forged ahead with the campaign in the style which Bernbach, Krone, and Koenig had set. In less than a year, Koenig had left to set up his own agency with George Lois, their big fallout yet to come. But there were plenty of other brilliant writers to carry on the idea, amongst them Bob Levenson, who went on to write the definitive book about the agency’s groundbreaking creative output, Bill Bernbach’s Book. Other art directors, too, would come along to work on the account, but all followed the template and attitude set by the original team.

In TV, too, executions were conducted with the same spare directness, but still with the knowing wit of “Think Small” and “Lemon.” In one, “Funeral,” the solemn occupants of a long funeral cortege of huge cars are shown one by one as the voice of the deceased intones over each:

“I, Maxwell E Snavely, being of sound mind and body, do hereby bequeath the following: To my wife Rose, who spent money like there was no tomorrow, I leave $100—and a calendar. To my sons Rodney and Victor, who spent every dime I ever gave them on fancy cars and fast women… I leave $50—in dimes. To my business partner Jules, whose only motto was ‘spend, spend, spend’, I leave nothing, nothing, nothing. And to my other friends and relatives who also never learned the value of a dollar—I leave a dollar.” At the end of the procession we see a young man driving a VW Beetle, clearly upset. “And finally, to my nephew Harold, who oft times said ‘a penny saved is a penny earned’ and who also oft times said ‘Gee Uncle Max, it sure pays to own a Volkswagen’, I leave my entire fortune of one hundred billion dollars.”

In another, “Snow Plow,” one of the consistently most admired TV ads of all time, principally for its simplicity, we see a car covered in snow traveling through heavy drifts to a shed where the driver gets out and opens the shed doors. We hear the roar of a powerful engine and he drives out on a snow plow. The voice-over says just twenty-seven words: “Have you ever wondered how the man who drives the snow plow—drives to the snow plow? This one drives a Volkswagen—so you can stop wondering.”

Ad after ad after ad, the same playful self-deprecating wit, the same chatty, knowing but economical copy—and always the same instantly recognizable layout and look. Very few people ever appeared in the ads, there were almost never any props that weren’t directly part of the car and very rarely was it shown against anything other than a white background.

Further DDB ads for VW, from 1963–80. VW advertising is still with DDB today.

THE CAMPAIGN’S IMPACT goes way beyond just VW, DDB, and the New York advertising scene of the early sixties. This campaign, more than any individual ads or campaigns that had gone before, epitomizes the Creative Revolution, and that revolution changed the face of advertising. Ohrbach’s, Levy’s, El Al were all terrific pieces of work, but none of them was a nationally-advertised brand competing in a mainstream product category.

Of course there had been people creating entertaining, witty, simple, and sympathetic advertising before, people who recognized a value in directness and candor. But they tended to be in isolated pockets and their efforts were easily snuffed out. They were shouted down by the orthodox who believed that empathy had no place in advertising; that anything other than the tried and tested was too risky; that any money spent on making friends with your potential customer was money wasted; that simple repetition, like the pounding of a jackhammer, was the most effective way to get a message to stick; that he who shouts loudest gets heard clearest; that more is more.

These people will forever be confounded and bewildered by the early VW ads, wondering how those who did them ever had the nerve. The consistency of approach and the high standard of thinking has ensured that to this day, when many DDB agencies around the world still handle the VW account, generations of creative people who have followed the original team more than half a century ago feel obliged to try to live up to their standard. Today’s VW advertising is still consistently winning awards and selling VW’s across the globe.