‘You want some respect? Go out and get it yourself.’

DON DRAPER TO PEGGY OLSEN MAD MEN

Krone, still dubious about the campaign said later, ‘I finished up three ads, went on vacation to St Thomas, depressed, came back two weeks later, and I was a star.’

Mad Men’s Don Draper completely missed the point of the ‘Lemon’ ad; ‘I don’t know what I hate about it most’, he said. But everyone was talking about the campaign and it wasn’t just people in advertising. College students had the ads posted on walls and curious customers were strolling into VW dealerships quoting the copy.

The irony of the VW campaign launching just one year after Detroit’s most catastrophic marketing failure, the launch of the Ford Edsel, shouldn’t be missed. The two case histories, one for a grotesquely overblown and glitzy automobile launched with unprecedented levels of Madison Avenue flatulence, the other for an honest and functional car announced with self-deprecating but intelligent wit, illustrated perfectly the gulf between DDB and the rest of the business.

One aspect of the Edsel disaster was not lost on Bob Gage. As he half-mischievously put it, ‘There is a great danger in research as a basis to work from. One of the biggest flops of the century was the… what was the name of that car? I don’t even recall it now… which was an entirely researched design. It had everything everybody wanted, except that nobody wanted it.’

This was heady renegade stuff. This was an agency with a major success on its hands desecrating the altar at which Madison Avenue worshipped, laughing at research. The effect on the rest of the business, particularly the new young creative people, was explosive. At last they had a champion who proved that agencies didn’t have to be run (and ads didn’t have to be done) in the old tired way, and that a creatively-oriented agency could credibly be held up as not just a creative but a business success.

There were other small pockets of creative endeavour around New York. CBS under Bill Golden at TV and Lou Dorfsman at Radio had acted as a sort of graphics finishing-school, with a stream of future first-class designers and art directors passing through in the mid to late 1950s. Herb Lubalin, a lifelong friend of Dorfsman, who gained notoriety in 1963 as the designer of the eventually banned avant-garde erotic magazine Eros, was Creative Director at Sudler & Hennesey. A noted experimenter with type, Lubalin, like Golden and Dorfsman, attracted a greater share of future creative award winners than this small, mainly pharmaceutical agency should logically have had. Bob Kuperman, later to head the VW group at DDB, Carl Fischer, one of New York’s leading advertising photographers for four decades, and George Lois were just three of them.

But none of them had the critical mass and national fame of DDB – John Kennedy, anticipating his 1964 presidential campaign, was said to have asked his staff about ‘the VW agency’. And critically, in the eyes of the young iconoclastic creative people pushing their way upwards, it was recognised to be ‘Bernbach’s place’, an agency led by a copywriter, as opposed to an account man.

Jack Dillon explains the implications of this when describing life at DDB as a writer later in the sixties: ‘There are a lot of writers and art directors in other agencies who, I’m sure, are very creative and able. But they are not working for agencies run by a writer or an art director. They are working for agencies run by businessmen.’

Referencing the early days of advertising agencies, he continues, ‘Writing ads was offered as an extra service by a businessman, not as the main thing that an agency did… its status had already been established. Creative people were and are usually under non-creative people. Bill Bernbach changed this. Bernbach was a copywriter and… he knew what good and bad advertising were.’

Many times since, creative leadership has proved to be less than dazzling. But Bernbach, with Mac Dane and Ned Doyle, was building a glittering business, both financially and creatively. And the thinking amongst the new creative community was if he can do it, so can I.

One person who had already tried was Fred Papert. He had written his first copy in the 1940s for Woolf Brothers men’s clothing store in Kansas City while working there as a salesman to pay his way through a journalism course at the University of Missouri.

He had a series of jobs as a ‘ragamuffin copywriter’ at Benton and Bowles and Y&R, and then became creative director at Kenyon and Eckhart. He was fired from that company while working on the Pepsi account, for which he had wanted to do experimental photography at the agency’s expense. Joan Crawford, the wife of the Pepsi President, vetoed his request. Papert objected, and summoned by his boss told him no matter who they were, clients shouldn’t tell the agency what to do with its own money. His boss said ‘You’re right. You’re also fired.’

At his next agency, Sudler & Hennessey, he met and briefly worked with the young George Lois, but he had already started to formulate the idea of having his own place. The line-up for his new outfit was a little eccentric; the four partners were two married couples, Fred and Diane Papert, both writers, Bill Free, an art director, and his wife Marcella, another writer. Sadly it didn’t last; within a year Papert was on the phone to George Lois at DDB, offering him his name over the door if he would take Free’s place.

LOIS WAS, AND STILL IS, a hugely energetic man, with so much going on in his head he often struggles to get it all out. He talks fast, in a thick Bronx accent, with frequent expletives emphasising his absolute views. Things – any things – are either sensational or a piece of shit, an idea will either knock you off your ass or it’s the worst thing you’ve ever seen. The phrase George Lois is least likely ever to use? ‘It’ll do.’

He was born in 1931 and brought up in an almost exclusively Irish area of the Bronx. ‘The discrimination against my family from another immigrant population, the Irish, sure didn’t bother me, I literally had 25 to 30 fist fights with kids in my neighbourhood. I won all of my fights, then wound up being friends with everybody.

George Lois. One way or another, he’ll knock you off your ass.

‘I went to the greatest high school in the world, a place called Music & Art in New York. It was the greatest institution of learning since Alexander sat at the feet of Aristotle. I got this incredible education, it was kind of a Bauhaus education, 1945 to 1949. And I then didn’t know quite what to do, but I figured I better go to another art school because I was aged 17 and a half and I didn’t know where to get a job because it wasn’t a field where people were looking for talent. I mean, there weren’t many places you wanted to work at – you’d love to work for Paul Rand. You could try to do record album covers or book jackets, etc. So I went to Pratt Institute, paid for by tips I got delivering flowers for my father since I was a kid, because he expected me to be a florist.’

From Pratt he was taken on by Reba Sochis as the first employee in her rapidly expanding studio. ‘In just one day working for Reba, you could learn more than in four years at Pratt or Cooper Union. She was the toughest boss in the world, but she was also the sweetest woman you could hope to know.’ She was one of the biggest influences on his life, a genuine pioneer; while female copywriters were comparatively plentiful, female designers were almost unheard of, let alone one running her own studio.

After military service in Korea Lois returned to New York, first to CBS, briefly to Lennen and Newell, where he overturned the agency chief’s desk because he’d been rude about his work and then to Sudler & Hennessy, where David Herzbrun first met him: ‘George Lois was a tall Greek kid with a big nose and a big lopsided grin. He looked as if he’d been nailed together from scrap building materials’. He described ‘the loose limbed way he walked and the way he talked with his hands, his shoulders hunched over’.

Herzbrun may be being a little harsh; a contemporary picture reveals strong-jawed matinee idol looks, and in Lois’s own words, ‘I was far better looking than Don Draper’. He and Herzbrun were teamed together, while Fred Papert, who was metamorphosing into an account man, was busy trying to get business for the agency. But it wasn’t easy, as Herzbrun recalls:

‘George had a way of making clients nervous. If they appeared to have any doubts about our work, he could be counted on to say something like “You fuckin’ crazy? This is the best fuckin’ campaign you saw in your fuckin’ life”. This speech was usually delivered in a tone of mixed fury and contempt while George loomed over the clients with fists clenched.’ His street-fighting days were certainly not finished; it’s possible they’re still not over, as he claims to have been in a fight during a recent basketball game in which he was playing – at the age of 79.

BY 1959, Lois had already done noticeable enough work to breeze into a job at DDB, leaving Papert and Herzbrun behind. His first year was sensational; by his own admission he managed to upset just about everyone at DDB, from Phyllis Robinson and Helmut Krone down, and win more major awards than anyone else. It’s possible the two were connected; his lips are never far from his own trumpet and no set of rules was ever going to constrain George.

It may seem counter-intuitive to find that within an organisation as radical as DDB there were already rigid mores and inflexible cultural tics. But you’ll frequently find that creative people within advertising agencies are amongst the most conservative – and tribal – on earth, and they don’t like their boat being rocked.

George’s first mistake was to spend the weekend before he joined painting his office and moving in his own furniture. Cutting edge though their advertising may have been, DDB’s offices were grey and almost dowdy, and George’s brilliant white walls and Eames chair stood out as a belligerent style challenge from the new boy. Then his energy, bellicosity and irrepressible confidence irritated enough people that eventually a deposition of creatives went to see Bernbach to complain about him. Bernbach listened to them and said (and bear in mind this is George’s story), ‘You don’t understand – George Lois is a combination of Bob Gage and Paul Rand’. Could there be higher praise?

Robinson had already called Lois in to admonish him for rudeness to Judy Protas over an idea he’d had for the news broadcasts for CBS television, then a DDB client: ‘I broke it down into 24 small space ads all throughout the newspaper that said 1 PM, 2 PM, 3 PM and each ad was an ad that said every hour on the hour, so when you looked through the paper you saw 24 ads, dominating the paper. It was a sensationally brilliant way to do something… and the writer comes in… and she says, “No, no, no, no George, you don’t understand, we at Doyle Dane don’t do small space ads, we only do big ads”, at which point I said “Get the fuck out of my room.” In fact I told four or five writers to get the fuck out of my room. Until Phyllis Robinson called me in and tried to chew me out, we wound up being great friends afterwards, but instead of her chewing me out I chewed her out and told her that she’d got constipated writers.’

Woman or no woman, gentleman or no gentleman, you don’t tell George Lois what is and isn’t ‘done’ without running the risk of a stream of profanity, or worse. This doesn’t make him an animal; it makes him passionate about his work. Ron Holland, a copywriter who worked with him for many years, says he is ‘almost Edwardian in his politeness with people’ and he will indeed treat you with a quiet, warm courtesy. Just don’t tell him what to do on his layout pad.

When he got Papert’s call, Lois didn’t linger long. Although being part of the DDB creative department was, as art director Len Sirowitz later said, ‘like being a team member for the 1927 New York Yankees’, the only logical next step was his own shop. And it hadn’t escaped his notice that no agency had ever set up with an art director as a partner – he would be the first. He had no doubt they could improve on what Bernbach was doing. His only condition was that he bring his own writer.

LOIS’S FIRST CHOICE was Julian Koenig, white-hot from his almost public fame as the writer of the VW ads. He immediately agreed, for two reasons. First, he’d been knocking around advertising for ten years and he, too, was curious about branching out, to see if he could do it on his own. It was one of those ‘will I spend the rest of my life wondering?’ moments. Second, he had recently experienced an aspect of Bernbach’s character that had irritated and annoyed him.

‘I wrote an ad for Ancient Age bourbon. Bill went down to the client – copywriters didn’t but the account people and Bill went. He came back and stood in the middle of the art department and said, “They loved my line”. And I said, “That’s my line, not yours”. And he said, “No, it’s my line.” So I called over Bert Steinhauser who I’d done the advert with and said, “Whose line is this?” and in true heroic form he said, “I forget”.’

It wasn’t an isolated incident. Three years before, in March of 1957, Time magazine had published a brief piece on the agency, specifically mentioning Judy Protas as the writer of the Ohrbachs ‘Cat’ ad. Bernbach immediately leant on the magazine and two weeks later a very similar piece ran which, without direct reference to the issue, made it clear that Bernbach was the author. Although Protas had written the body copy, which is superb, the idea was Bernbach and Gage’s. So some of the credit was justified – but was the effort to capture it?

The indignation of the creative people was leavened by the fact that they accepted that as the creator of the environment, Bernbach could claim partial involvement in all their work. (Don Draper makes the same point to Peggy Olson when she complains that he has taken an award for an ad that she wrote.) Even Koenig, irritated as he was, could see Bernbach’s position: ‘Everything in the agency was his. I realise that he thought it was his ad, in the sense that it would not have existed if it had not been for him.’ But Koenig had also had a run-in over a tyre commercial with Joe Daly (the Head of Accounts), and was in a truculent mood.

He went to meet Papert and they immediately recognised each other from the racetrack – four decades later they were still going to the races together – and to a mixture of incredulity and ridicule on the part of the rest of the DDB creative department, the deal was announced.

PAPERT KOENIG LOIS (PKL) opened its doors on the 36th floor of the Seagram Building on 1 January 1960. The offices had previously been those of Papert & Free which, coincidentally, Lois had helped them secure a year earlier. Edgar Bronfman of Seagrams had been having trouble letting whole floors as he wanted, and Lois got a tip through Bronfman’s son-in-law, a friend of his, that a deal could be struck.

Five people occupied the office on that first day. Says Lois, ‘I felt off-the-wall excited – and nervous and apprehensive. I didn’t know if it was going to work out.’ Their first client was The Ladies Home Journal, inherited from Papert & Free, quickly followed by Dilly Beans. For these two clients, one staid, one small, they managed to create eye-catching work and they were off and running.

The offices were stylish and hip, the organisation cool but chaotic. A visitor once found staff wobbling aimlessly around the office on French Solex motorised bicycles. It looked like a time-and-motion-inspired efficiency initiative; in reality they’d taken on the account and then discovered the bike had no retail outlets in New York. So they decided to become not just advertising agent but dealership as well. It was not a success – no one had bothered to find out that a licence was necessary to ride them on the streets, and the surplus stock ended up in the office.

But within a few months, to give them gravity, they hired an experienced marketing man, Norman Grulich. The agency’s work was terrific – possibly even more concentrated than DDB, the ballsy innovative campaigns streamed out and the cream of New York creative talent had a new path to beat. ‘People wanted to come to us because we were free spirits’, says Papert. An ice cream truck driver named Ron Holland decided to switch to a career in advertising based on an ad he saw for Dilly Beans – he wanted to work with people who could write a line as subversive as ‘If your dealer doesn’t stock Dilly Beans, knock something off the shelf as you walk out’.

Through Bronfman’s company, Seagrams, PKL picked up Wolfschmidt vodka. New Yorkers were startled by a campaign that personified the bottle as a man promiscuously picking his partners from suitable ingredients for a vodka-based cocktail. A vodka bottle flirting with an orange was a long way from the tuxedoed and evening-gowned stiffs that were usually featured in classy alcohol advertisements. It was also, on the threshold of the sixties, deemed a little risqué – The New Yorker refused to run the ‘Who was that tomato I saw you with last night?’ version.

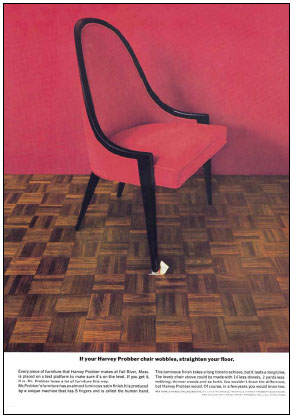

Of course, having an ad banned for being risqué, with the notoriety that brought, was meat and drink for the renegade agency. And not all their work was edgy; Koenig was still ever the elegant writer, and Harvey Probber Chairs got the velvety persuasive treatment in an ad whose authorship is still to this day in vigorous dispute between Lois and Koenig.

THE WORK THAT ANNOUNCED their arrival as a fully fledged, grown-up agency capable of handling national brands came about by a succession of lucky bounces.

One Saturday morning after a major snow storm, Fred Papert decided to walk to the office to retrieve the gloves he’d left there the previous evening, towing his kids on a sled behind him. In the brief time they were in the office the phone rang. It was Xerox asking if they’d like to pitch for the launch of their new photocopier, not a difficult question for Fred to answer. He later learnt that one of the reasons they won the business was that Xerox were impressed he was working on such an inclement Saturday morning.

The disputed Harvey Probber Chair advertisement, created by George Lois and Julian Koenig.

1960 PKL advertisements for Wolfschmidts, by George Lois and Julian Koenig.

The call itself was also due to fortuitous circumstances. DDB had been offered the business but they couldn’t handle it because of conflict with Polaroid – clients have always been hyper paranoid about having their business with an agency that is simultaneously handling a company who could even remotely be considered a rival.

According to Julian Koenig, ‘Ned Doyle called me up and sotto voce told me about an account we might be able to get and says “but don’t tell Bill”.’ Xerox had asked Bernbach to give them a list of agencies he would recommend and ‘he made a list of ten including some quite lugubrious ones, but he omitted us… Bill was an old friend and he would embrace me but he did everything he could not to help. He was offended that we (a) left and (b) succeeded.’

Bernbach did have an agenda. Referring to PKL, Bernbach had told Edgar Bronfman, ‘There’s a difference between being smart and smart alec’. Bernbach didn’t like his children growing up and leaving; when George Gomes, a DDB art director setting out on his own as a commercials director, went to see him to say goodbye, all Bernbach said before he turned his back and walked away was, ‘Yes, I heard you were leaving’. Gomes later heard through former colleagues in the agency that Bernbach had forbidden the department to use him.

There is always the possibility that he genuinely didn’t think PKL was right for the job, but if so, in this instance his famed creative radar was out of tune. PKL, and specifically art director Sam Scali and copywriter Michael Chappell, turned in a demonstration commercial about as perfect as can be made. But even in this, fate took a hand.

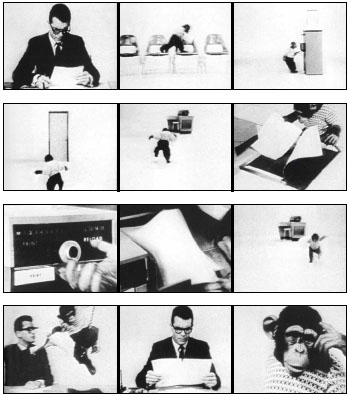

To illustrate how simple it was to use, they had a small girl make copies on the machine, in real time. It was straightforward, direct, carefully written and impressive enough to irritate competitors into complaining to the networks that the complexity of operating the machine was being understated. PKL’s answer was a typical mixture of belligerence and brilliance; not only did they reshoot the whole commercial, in front of TV executives, but instead of the girl they used a chimpanzee.

The resulting commercial, with almost no voice-over and the simplest of camera work and editing, is mesmerising. The chimpanzee is asked by a desk-bound executive – like it happens every day – to make a copy of a document. He takes the document, waddles to the machine, confidently and competently follows the procedure and insouciantly hands the two sheets to the executive, whose only question is ‘Which one is the original?’

The TV ‘Chimp’ advertisement for Xerox: monkey see, monkey do.

BY 1962 CONFIDENCE was high, billings were at $17 million and, true to their iconoclastic behaviour to date, they took one of the most radical steps ever in the history of advertising – they became the first agency to go public. The move was loudly opposed by just about everyone in business. The righteous justification, intoned for public consumption by agency chief after agency chief, was that ‘we are in the service of our clients, not anonymous shareholders’. The real reason was that few successful agencies wanted the balance sheet scrutiny that would necessarily follow the announcement of a flotation.

Agencies were remunerated by a commission from the amount their clients spent on their media exposure, a hangover from the days when their main business was the selling of space. It meant in theory – and very often in practice – they were rewarded for not doing new work; if the same advertisment ran year after year, they would earn their commission for having done nothing more than buy the time or space from the broadcast or print media. It also meant that they had no incentive to keep media expenditure down. On top of that, revenue was bumped up by commission charged on production costs for print and TV executions, as well as on research and other ancillary services. All of which meant these advertising agencies were productive little cash machines from which their owners could withdraw more or less what they wanted, when they wanted it.

Consequently, most of them lived – and rewarded their senior people – far more handsomely than their equivalents at the client companies, something the clients could suspect but never prove. But once you go public, the covers are off.

Fred Papert, whose idea it was, figured he could reward himself and his partners from the pool of wealth that shareholders brought. ‘Salaries were getting too high – stock was an alternative. It was the route to real wealth, we would have made a fortune.’ And they weren’t yet fat enough to have left any skeletons in their financial cupboard.

Lois articulated a more high-minded motive, albeit in a characteristically abrasive way. He stood received wisdom on its head and claimed that public ownership would make them better partners of their clients. ‘The concept of public ownership puts us on a par with any company that produces a product. The image of our business no longer has to be that of shufflers who make money because they have a slick line of talk. No pride, just talk.’

Despite their howls of protestation, by the end of the decade more than twenty other agencies had sold stock, and five of the top ten were public companies. For PKL, very soon it was seen to be the genesis of the sad, slow disintegration of the agency. Once you have shareholders, you have to deliver to someone else’s expectations; doing the work you want to do, regardless of profitability, is no longer viable.

Amongst the influx of clients excited by the freewheeling new agency was the Daddy of them all, then and now, Proctor and Gamble, the undisputed king of packaged goods.

In retrospect it’s obvious that P&G, who were always committed to Rosser Reeves’ school of advertising, should never have gone to PKL. The last thing they wanted was any sort of originality and certainly not controversy; they wanted only that which had been done a thousand times before, anathema to PKL’s founders. But like so many other clients and agencies, they were intrigued by the new creativity and they decided to give the agency a try to see if they were missing something.

It’s slightly more forgivable that PKL should have taken the business. There was after all a lot of money and huge credibility to be gained – if you were solid enough for P&G you were solid enough for anyone – and there were now also shareholders to satisfy. They probably made the same mistake as literally hundreds of proudly creative agencies around the world since; that of taking unimaginative left-brained clients in the hope that they would be the ones to tame the beast.

According to Papert, Lois didn’t like the idea. ‘And he was probably right. It made our agency just like any other.’ All three – Papert, Koenig and Lois – now say that it was probably the beginning of the end for them.

The cultural fit is so important in a business where no matter how much research you do (and PKL shared DDB’s deep suspicion of research), so many creative decisions are simply a matter of opinion. If your judgement derives from a very different outlook than that of your clients, fissures in the relationship will appear very quickly. While the agency respected P&G as a company, they had very little respect for their advertising taste, which was hardly surprising given their showreel. One example of the agency’s frustration was to be told they couldn’t show a pile of dirty washing in a Dash soap powder commercial, because it was… dirty.

So here we have the excitable Greek art director and the one-time beatnik Jewish copywriter sitting down to discuss ideas with preppy MBAs clothed by Brooks Brothers, whose idea of a creative discussion centred on the colour of the dress worn by the obligatory happy housewife in their floor cleaner commercial. ‘Let’s get down on all fours and see this from the client’s point of view’ was a popular phrase around town.

Defiant words, but as Bob Levenson was to say later when DDB ran into problems with their slice of P&G, ‘You can’t have Proctor & Gamble on your terms. You have Proctor & Gamble on Proctor & Gamble’s terms’, and that includes careful casting of the people who work on their business.

Papert recalled that though Koenig could be sharp – once at a P&G internal advertising awards ceremony he thanked all of the members of the client team ‘without whose help the job would have been done a lot quicker’ – but he could also be ‘gentle and nice’.

On the other hand, he says of Lois, ‘George is in your face. He had a problem – he wanted to work on P&G cat food but got asked off. People who like cats don’t want smart ass stuff thrown at them.’ And at PKL it wasn’t always just ‘stuff’ that got thrown in your face.

PKL HAD A REPUTATION for brawling. In fact, the agency became known in New York as Stillman’s East, after a famous boxing gym on the West Side. As a way of settling differences of opinion, a robust physicality was never far from the surface, even if sometimes it was theatrical, like the occasion when Lois climbed out onto the windowsill of his Matzos client’s office and threatened to jump if they didn’t buy his ad.

Jerry Della Femina claims that one former writer tried to sue the agency because the atmosphere of intimidation kept him from concentrating on his work. But Lois denies that fighting was an everyday occurrence, even though he admits to searching for three days for a member of staff who had punched the head of TV: ‘The guy didn’t come in for a week’, he growls.

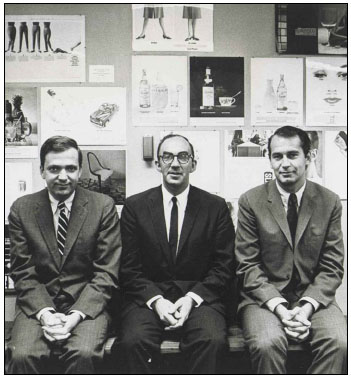

From left to right: Fred Papert, Julian Koenig, and George Lois. A Wasp, a Jew and a Greek – the prototype sixties Creative Revolution agency.

An account handler, Carl Ally, is alleged to have punched George Lois in the stomach. Today, Lois is indignant at the suggestion: ‘Ally punched me? Are you crazy? I’d have laid him out. It was Papert he went after!’

Illustrating the macho atmosphere at PKL, Lois recalls, ‘We had the best basketball and softball teams in advertising. Our basketball team played in the Bank league, which had all-American college guys on their teams. The agency was loaded with strong guys. We were all depression babies, a lot of ethnics, a lot of street kids. It wasn’t like walking into an Ogilvy or Benton & Bowles, it was a place where men were men. We’d play in Bedford Stuyvesant where no white people went.’

It’s sort of appropriate that when it came to doing an ad for their women’s fashion store client, Evan-Picone, the models were dressed as mobsters and their molls. It’s equally appropriate that the mobsters were Charles Evans, the client; George Lois; an unidentified man from the PKL art studio; and Tony Palladino, an art director at PKL. Later, Palladino was to take the role rather too seriously in an incident in London which today seems comical but at the time was near tragic.

In 1964, PKL had opened an office in London for no particular reason other than that, according to Lois, Papert was an Anglophile and wanted someone to book his West End theatre tickets. Two New York PKL staff members were sent over to help set up and run the office: Ron Holland and Tony Palladino. The man appointed to head the Knightsbridge agency was a red-haired, dark-suited English aristocrat, Nigel Seeley (later to become Sir Nigel), a former client of PKL in New York. An ex-Army officer, Seeley had been trained in unarmed combat.

Says Peter Mayle, who would become PKL London’s creative director, ‘We all thought he was a toff because he took snuff and his uncle was an earl or a duke. When the uncle died, Nigel inherited the title (and his uncle’s crested socks, of which he was sinfully proud). I liked him a lot, I never found him disdainful but he certainly had a patrician manner. This might very easily have upset people.’

George Lois, who knew Palladino from childhood, says, ‘Tony was a tough kid, ready with his dukes. He grew up in East Harlem, black neighbourhood. Number of times I’d leave school and find Tony having a fist fight with a couple of black guys. I’d have to drop my books and start swinging.’

You can see what’s coming. It arrived about an hour before the agency Christmas party. Mayle recalls, ‘Nigel was in his office having a drink with one of the boys. I don’t know what he’d done to infuriate Tony but when he went into Nigel’s office it wasn’t to wish him Merry Christmas. Strong words must have been exchanged, causing Tony to attack Nigel with a view, or so I heard, to strangling him. Nigel stuck out a hand to defend himself. The hand was holding a glass of champagne. The glass broke off in Tony’s neck, not far from the carotid artery. Nigel’s hand was also cut open. There was an impressive amount of blood which, as Nigel and Tony moved out of Nigel’s office, dripped all over the agency – floor, desks, door handles, account executives’ trousers, everywhere.

‘We spent hours mopping it up, since we had a new business presentation the next morning. Someone had the presence of mind to take Tony to the nearby St George’s hospital and he was never seen in the agency again. I guess that once his wound had been sewn up he got on the first plane to somewhere less violent. Like New York.’ He had indeed. He was on a flight the next day. It seems that the Stillman’s spirit travelled well.

IN 1963, Lois was the New York Art Directors Club Art Director of the Year. Said Herb Lubalin, ‘Nobody has the right to be so young and so successful.’ And life was good at PKL. They’d outgrown the Seagram premises and moved to Rockefeller Center, where the key people had offices overlooking the skating rink. One of their growing list of accounts was Restaurant Associates, a company that ran some of the very best eateries in Manhattan, including the hugely fashionable Four Seasons on the ground floor of the Seagram Building. It was practically the agency canteen; Lois, hair slicked back and dressed in one of his uber-sharp Roland Meledandri suits a Madison Avenue tailor whom Lois claims even Ralph Lauren worshipped, had lunch there most days. Top management could eat at whichever of the restaurants they wanted, whenever they wanted, for free. On Saturday nights, Papert and an OB&M copywriter friend Bob Marshall and their wives would see how high they could rack up the bill for dinner; $75 was a satisfying achievement one weekend.

Chaos still reigned. There were, as Papert puts it, ‘All sorts of internal shenanigans. At one point I got fired – but I just kept coming in. It all blew over.’ New accounts arrived, often in spite of their best efforts to repel them. At a pitch to National Airlines, the agency showreel was first run backwards, and then upside down. In front of an increasingly transfixed client Papert kept up a stream of wisecracks and small talk while the film was reloaded. The projector was ready, the signal was given and the film spooled smoothly all over the floor.

‘We just got up and left – what’s the point? We were in the car, just about to pull away from the car park and there’s a tap on the window. It was Bud Maytag, the National Airlines client. ‘OK, we’ll do it’ he says. ‘Do what?’ ‘We’ll give you the business. At least you’ve demonstrated you’re not just slick salesmen.’

With the problems brought about by the flotation and the tenure of P&G yet to materialise, it didn’t matter what the agency did, it worked. Everything was turned on its head. The work you did and the way you did it, the people you hired, the way they behaved, even the way they dressed. If there was a new rule, it was that there were no rules. A new account man, Ted Levinson, on asking for an agenda for a new business meeting, was told by Papert (his boss, remember), ‘Are you kidding? We don’t do agendas.’ There was a new pride – the obsequious ad hustler was dead. In his place was the assertive new ad man who would happily tell you that you may know all about your product, but don’t even think about telling him anything about advertising.

Account executive Phil Sussbrick was with Lois at Quaker Oats in Chicago, presenting some new ads, when Lois got to one of which he was particularly proud. Sussbrick was appalled – but not particularly surprised – to hear him preface the layout with, ‘And if you don’t buy this, you can kiss my ass.’ Then he thought again, changed his mind and said, ‘No, you can kiss Sussbrick’s ass’.

In Jerry Della Femina’s memoir he writes of a joke circulating Madison Avenue featuring the switchboard operators of various agencies. There were many variations, characterising the way the business was evolving.

‘Good morning, this is Ogilvy and Mather – how can we oblige?’

‘DDB, Shalom.’

‘This is PKL – who the fuck are you?’