‘We’re all here because of you. Everything we do is to please you.’

PEGGY OLSEN TO DON DRAPER MAD MEN

Within the overall discipline that all advertising exists only to sell and everything else was secondary, the creative people at DDB were given complete freedom of the lay-out pad. During a 1965 interview on life at DDB, copywriter Ron Rosenfeld likened the agency to Summerhill, a leading progressive school in England. It was a touching analogy. Summerhill was almost free of rules, with a philosophy that allowed children to experience their full range of feelings. The school accepted that the freedom the children were given to make their own decisions always involved risk, and so allowed for mistakes to be made.

This was eerily reflective of Bernbach’s attitude at DDB, and the fully-grown and otherwise hard-bitten creative people were almost dizzy with adulation of their teacher.

‘We were working for the approval of one person – Bill Bernbach,’ says art director Bob Kuperman. ‘To get your ad pinned up on his “Best of the Month” board, they wanted that more than anything, more than any awards. They were only juries. But this was Bernbach.’

‘We did it to see Bill’s eyes light up’, said Bob Gage.

This near self-abasement had its material consequences. DDB were dreadful paymasters, knowing that people would take a cut in salary to work there. Kuperman turned down an offer from Delehanty, Kurnit & Geller that would have trebled his salary. Later in the sixties, when the size borne of its very success became the seed of its own slow decline and DDB lost some of its passion, the creative people were surprised by how far they’d fallen behind in the salaries they could command.

But for the time being they didn’t care. In return for their cultish submission within the Church of Bernbach they were granted holy status without. If you worked for DDB you moved in rarefied air, and you knew it. Jim Raniere, an art director, remembered the parties that production companies would throw around Christmas and holidays: ‘You go into this huge room with all the advertising people in New York going to dance and eat and Doyle Dane used to stand to one side, not mixing. I think we were, at that time, a little self-involved. Well, we were doing the work so we felt we were different from the way they were doing it.’

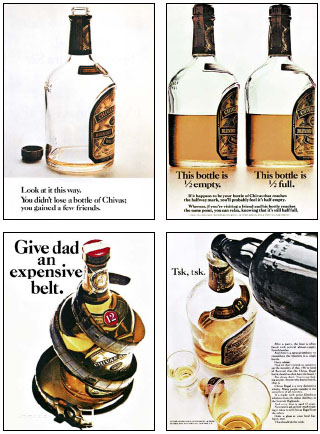

The work continued to dazzle. Coffee of Colombia was sold with bonhomie through a good-natured fictitious coffee grower, Juan Valdez. A campaign was created for the Jamaica Tourist Board that was as literary and elegant as anything Ogilvy had ever written for the British Tourist Authority. Some of the sly wit of Orbach’s and VW showed through in a Chivas Regal campaign of such clever conviction that it turned an ordinary whisky into, in its own unashamed words, the ‘Chivas Regal of Whiskies’.

THE NEXT CAMPAIGN to attract the same attention and admiration as Volkswagen was Avis. Robert ‘Bob’ Townsend, a former American Express executive, had been appointed by banker Lazard Freres in a last ditch attempt to save the ailing car hire firm, which had been leaching money for eleven consecutive years. His approach was about as unconventional as his eventual advertising.

As Clive Challis reports in Helmut Krone. The Book, ‘Townsend dispensed with a secretary, fired the Avis public relations department, insisted that management undergo the same training as the field staff, cut meeting times by insisting that everybody stand up throughout them and later wrote the bestseller Up the Organisation. [It] went into several reprints and became something of a handbook for an alternative management style.’

When he called Bernbach to outline his problem and asked how they would work together, the answer he got was so extraordinary that Townsend wrote it down.

‘What you do is let us have 90 days to learn your business, and then you run every ad where we tell you to put it and just as we write it. You don’t change a thing.’ He then urged Townsend to call all DDB’s existing clients for a recommendation and that was it – The Presentation. Take it or leave it. Townsend couldn’t resist.

The writer assigned to the business was Paula Green. Born in California in 1927, she’d come to New York and got a job as secretary to the promotions manager of True, a men’s magazine. He involved her in every aspect of magazine production, including writing. When he left she took his job but then went on to join the promotions department of Grey advertising, where she could write full time.

By 1956, DDB was already becoming an interesting agency and as she’d met Ned Doyle at Grey she gave him a call. He arranged for her to come in to meet Phyllis Robinson, after which she was hired. She was teamed up with Helmut Krone with whom she’d never been paired before. The relationship was not always harmonious – Green at one time threatened to resign over Krone’s attempt at ‘improving’ her copy – but between them they produced a campaign every bit as radical and successful as Krone and Koenig’s VW work.

It was not dissimilar – candour was its heart, its impact and its leverage. The opening layouts were a direct reversal of the VW layout: big headlines and copy, small picture. There was one radical advertising departure – there was no logo. Krone predicted that the consistency of the distinctive look would bring brand recognition, and he was right.

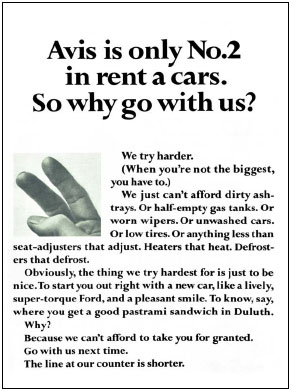

As with the VW campaign, the agency capitalised on Avis’s immediate apparent disadvantages. Far from hiding the fact that they were a distant second to Hertz in size, the team turned it into a potential benefit to the user. In the very first ad they asked the question, ‘Avis is only No. 2 in rent a cars. So why go with us?’ The answer was the campaign theme: ‘We try harder’.

To conventional contemporary advertising eyes ‘We’re No. 2’ was a shocking misjudgement, a page one error. Indeed, it failed research tests – 50 per cent of respondents said they didn’t want to be associated with anything except number one. But Bernbach said it should run anyway; he argued that while ‘We’re No. 2’ had the more immediate impact, the irrefutable follow up logic of ‘We try harder’ would soon become convincing.

Bottled sophistication; the Chivas Regal campaign by DDB ran from 1963 to 1970.

The Avis campaign by DDB (1962 to 1966), created by art director Helmut Krone, and with copywriters such as Paula Green and David Herzbrun.

The impact was undeniable. Fred Danzig, then a reporter on Ad Age, recalls that the opening ad came into the office on a Friday ‘and broke as a Last Minute News item in that Monday’s issue. I remember how we gathered around the ad and simply went nuts… the audacity, the originality, the freshness, the life, the sassy spirit… It forever changed the way Madison Avenue – and the rest of us – communicated to the world.’

With short succinct copy, a succession of ads made the same point. As an idea, it was more than an advertising promise. By publicly claiming, and committing to, ‘We try harder’, the service staff at Avis had to follow up. The organisation was dragged, almost shamed, into higher service levels by its advertising. In 1963, when the campaign started, Avis revenues were $35 million. The next year they were $44 million. To Townsend’s credit, a $3.2 million loss was turned into a $3 million profit in a single year.

For DDB, honesty was clearly proving the best policy and at times the candour was absolute, as on the occasion when David Herzbrun and Helmut Krone sampled the Avis offering for a trip out to the company’s Garden City headquarters. They were less than impressed with the car they were given and in two days produced the ad shown on the next page:

‘The writer of this ad rented an Avis car recently. Here’s what I found:’

Townsend hated it. According to Herzbrun, ‘It went against everything he believed about how to do advertising. It was negative. It kept on being negative. “Right”, we said. “And we want to run it”.’

A compromise was reached. They could run it as long as they told him exactly where and when it was going to appear, so he could make sure he never saw it again.

Townsend himself took the trying harder promise to its limit. One ad headlined his real phone number for anyone with a complaint to ring him personally. In the history of service business it’s difficult to imagine an example of a CEO demonstrating his commitment in a more direct way.

With Hertz publicly targeted in all but name there was bound to be an impact on the Number 1, but that was not necessarily Avis’s aim. They were just as happy to sweep up the custom from their competitors in third, fourth and fifth place, increasing their market share as number two. But it was hurting Hertz enough that by 1966 they felt they had to do something about it.

They called Carl Ally Inc.

CARL ALLY OPENED for business in Manhattan on 25 June 1962. He was an account man, but not as anyone knew them, then or since. Amil Gargano, Ally’s business partner for the best part of 30 years, describes the account people of the era as ‘… the Captains. They were the brass of the agency business and that’s how they conducted themselves. They never took their jackets off, their sleeves were never rolled up, their ties were always straight. They were incredibly boring – and then in comes one with his shirt tails out, his fly open, his tie loose, his hair mussed up… An English major from Michigan who would quote Shakespeare and swear like a longshoreman in the same sentence… An incredibly colourful person – and people were captivated.’

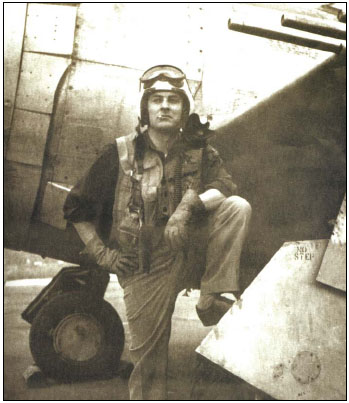

Five foot seven, stockily built and pugnacious, Carl Ally (or the Terrible Turk as he liked to call himself) was born in Detroit in 1924 to an Italian-American mother and a Turkish father. A fighter pilot in Europe in World War II and in Korea, winning both a Distinguished Flying Cross and a Presidential Citation, he never quite left the barrack room behind, despite his searing articulacy and intellect. Erwin Ephron, a media department head, remembers Ally’s short but devastating analysis to Hugh Hefner after a long and high-minded presentation on the quality of Playboy magazine’s original fiction: ‘Fine Hef – but take the tits out and see what happens’. A young copywriter, proudly showing the first cut of a commercial with an elaborate narrative obscuring the sales message, was urged to re-edit with the terse critique ‘too much foreplay and not enough fucking’.

After Korea he went into advertising in a small Detroit agency before moving to Campbell Ewald, a bigger outfit made grand by its tenure of the General Motors account. But it wasn’t long before he had one eye on the bigger opportunities for both him and the agency in their tiny New York office and he short-circuited the process of getting transferred with a startling piece of initiative.

While on vacation in Manhattan, he read in The New York Times that the Swissair business was up for grabs. He contacted them, got the agency on their pitch list, made the presentation single-handed and won the account. The first the Detroit management knew the account was loose was when Ally called them to tell them they’d won it.

Impressed, they agreed he should be based in New York permanently, not just for servicing Swissair but to expand the office.

The New York office was a sleepy hollow; a handful of functionaries going through the motions of handling a few quiet local offshoots of GM business. But Ally shook it up. He was, as Amil Gargano wrote in his book about the agency, Ally and Gargano, ‘an earthquake in a nursing home’, literally moving into the office and sleeping in a sleeping bag.

THE FIRST HELP ALLY needed was creative so he asked for James Durfee and Amil Gargano, a copywriter and an art director he’d worked with back in Detroit. Ironically for Durfee, he’d joined Campbell Ewald only because his previous agency, JWT Detroit, had wanted to transfer him to New York and he hadn’t liked the idea. But with his second New York offer in a year, he decided that fate was trying to tell him something and this time he agreed to move.

Amil Gargano was more than ready to go. Born in Detroit on 4 June 1932 to Italian immigrant parents, he showed early promise as an illustrator and entered the world of advertising as a paste-up artist at Campbell Ewald. Within just six months Gargano had been promoted to assistant art director.

Two years later, an art director new to the agency introduced Gargano to the New York Art Directors Club awards annual. It was an epiphany. For the first time he saw advertisments for Levy’s and Orbach’s and the work of Bob Gage, and that was when he asked for a transfer to the only place he wanted to be – New York. Ally’s Swissair win made that move possible, and in April 1959, Ally, Gargano and Durfee were together for the first time in Manhattan.

Ally quickly added to the Swissair win. His high-profile air force presence in the two wars resulted not only in the belief that he was the model for Yossarian from Catch 22 (a story promoted largely by himself but credible to those who knew him), but also in a huge contact list in the aviation business. Those contacts helped in the subsequent gain of the United Aircraft Corporation (UAC) account.

Carl Ally as a fighter pilot in Europe during World War II. Attitude? What does it look like?

His vibrant and usually oath-laden style was clearly paying off. But not everyone was finding Ally’s exuberance and energy infectious. Problems on Swissair and United Aircraft, clients that the company wouldn’t even have had if it hadn’t been for him, had ruffled the feathers of the top management. First, they objected to him taking Gargano and Durfee on a fact-finding trip to Switzerland, seeing no reason why he couldn’t go alone and brief the creatives on his return. (This was the same year several DDB staffers, creative people included, were making trips back and forth to Wolfsburg, Germany to learn about VW.)

Second, United Aircraft had not liked the campaign prepared for them and Ally was seeking the assistance of the Detroit management in getting it through. Instead, they backed UAC and, to the huge relief of the previous regime at the New York office, Carl Ally’s charismatic but disruptive spell in New York crashed and burned just two weeks before Christmas 1959, when he was summoned to Detroit and fired on the spot.

Shocked, dismayed and disgusted with the management, Gargano made every attempt to get out, but as the only place he really wanted to work was DDB and they wouldn’t even see his book, let alone him, he was stuck. Durfee, married with a child and living in Connecticut, had even less flexibility.

After a year without work, Ally was close to a breakdown. He was on the verge of going back to Detroit and starting over when Gargano suggested he talk to the lively new PKL, thinking it would be a meeting of minds – or at least attitudes. And he wasn’t wrong. George Lois recalls, ‘Account guys bored me, they were full of shit but when I met Carl Ally, I said, “Gee, the guy’s got blood running through his veins”.’ He thinks for a second and then adds, ‘Amazing that I liked him – he was a Turk and I’m a Greek!’

Ally was in his element, established in the sort of New York organisation he’d originally envisaged. ‘Wings and wheels’ being his forte throughout his life, he was happy on various automotive accounts, particularly Peugeot, but he became increasingly dissatisfied with his remuneration and particularly the partners’ refusal to allow him any company stock. So in April 1962, when his Peugeot client, Jim LaMarre, told him he was leaving to take up the job of marketing director at Volvo, Ally seized the opportunity and convinced LaMarre to allow him to pitch for the business with a new agency he would form around the account.

Durfee had by now moved back to semi-familiar turf at JWT New York, Gargano to B&B, but in nine months he hadn’t had a single piece of work published and when Ally approached them with the idea of forming an agency, both were ready to go for it.

They worked on the pitch after their normal working day. And, despite the fact that the limited resources and cramped timeframe caused the layouts to carry the brand name misspelt as ‘Valvo’ (Ally being Ally, some recollections inevitably have it as Vulva), they won the business.

GARGANO AND DURFEE are both mild-mannered, civilised, considered men. Even allowing for youthful brashness, they were a direct contrast to the pugnacious, occasional combatative style of their colleague. But together they created a campagin for Volvo that was probably the most confrontational – literally – in the history of US advertising to date. Until then, any product comparison in advertising was by implication only, and you never ever named the competition. Yet right from the start, in commercials and print ads, they not only named competitive cars but showed them as well.

The campaign had the same frank freshness of VW. Ad after ad reiterated the Volvo’s rugged construction and longevity, while ridiculing Detroit’s built-in obsolescence, which made the Volvo not the aspirational choice or the stylish choice or the sexy or high-performance choice – it made it the clever choice.

Following Volvo was another candid and compelling campaign for the New York automat chain, Horn and Hardart. As pioneer fast-food restaurants, the high quality of their food was belied by the basic surroundings. Simple meals, prepared fresh on the premises, were placed in small glass-fronted display boxes, released by dropping a nickel in the slot. It was low-budget eating but the advertising never claimed anything else. Quite the reverse, in fact – it claimed that the money saved on pretentious surroundings and elaborate service went on the one thing you’d want – good food.

Carl Ally’s Volvo campaign, the first direct comparison advertising.

The Carl Ally campaign for Horn & Hardart; a lesson in clarity and candour from Ed McCabe.

The campaign was written by a punchy, young Irish-American copywriter, Ed McCabe. From an underprivileged Irish background and a tough upbringing in Chicago, he left school at the age of 15 and took a variety of jobs. One of these was in an advertising agency, where he’d noticed that the copywriters seemed to do the least work and have the most fun, so that’s what he decided he wanted to do. He started writing spec ads in his spare time and getting them in front of as many people as possible. With that dedication he worked his way into a copywriting job at McCann Erikson Chicago in 1954, then on to New York in 1959, where he started at Benton & Bowles on the same day as Gargano.

As with Gargano, B&B’s old school style frustrated McCabe and he joined Carl Ally within a year of the start up. He eventually became the youngest copywriter ever elected to the One Club Hall of Fame.

His style is simultaneously direct and disarmingly conversational, writing with wonderful clarity. In contrast with the WASP copywriters of old, he spun the lines with tremendous energy and impact, using vernacular and slang. For some, McCabe is the copywriter’s copywriter.

WITH CHARACTERISTIC PRIDE Ally would say, ‘At DDB they like to goose the consumer – but at Carl Ally Inc we punch them on the nose’, appropiate from a man who once told a meeting of the Volvo sales force ‘You guys couldn’t sell c*** in a lumberyard’. And, from Hertz’s point of view, it wasn’t just the consumer that needed the punch, it was Avis.

So when representatives from Hertz called Carl Ally Inc to help them attack the Avis campaign they couldn’t have made a better choice. As the Ally presentation team told them, ‘You’re getting your asses kicked and it’s time to kick back’. Between 1963 and 1966 Avis’s market share had risen from 29 per cent to 36 per cent and Hertz had fallen from 61 to 49 per cent. It’s not too fanciful to suggest that, given another three years, Hertz could have been ‘Only No. 2’ and having to try very much harder themselves.

With a licence to get down and dirty, Durfee and Gargano were acutely aware that the world (well, the ad world at least) would be watching with more than usual interest. Responding directly to a rival in public in any field is often unwise and always highly delicate. The slightest false note could make you look petulant, worried or even downright rude. And even though Avis had started the fight, it was easier to be them. Everyone loves an underdog.

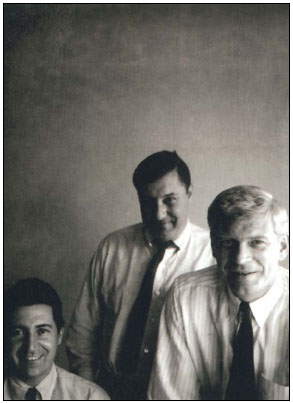

From left to right: Art director Amil Gargano, copywriter Jim Durfee and Carl Ally.

The looming rumble was going to be a spectacle for the ad business and all the heavyweights of the trade were filling the ringside seats, waiting for the initial counterpunch from Hertz. The team knew they had to be firm, but cool and confident, as befits a market leader.

Says Amil, describing an internal meeting to discuss the opening salvo, ‘Jim and I had put together a couple of pretty tough layouts… but we couldn’t get the first ad right. During a brief moment when the room went silent, John [Carpender, the account supervisor] spoke up. “Hey, what if we say ‘For years Avis has been telling you Hertz is number one’?”

‘Durfee finished the headline, “… now we’re going to tell you why”.’

And that’s precisely what Durfee and Gargano did. Hertz, aloof for four years, now reminded the customer why they’d got to number one in the first place – more outlets, more and better cars, money-back satisfaction guarantees, a hotline – and all with the sort of fond but crushing put-down from an older brother to a noisy sibling.

It was aggressive – but its good humour alleviated any nastiness. By playing Avis on their own turf, they even admitted to occasional mistakes, like an ad in which the only visual was an open ashtray with a single cigarette butt in it. Underneath there was a candid admission of infrequent failure, but only after a devastatingly precise demolition of Avis’s weaknesses. The barrage was relentless – it was always civil but never without the iron fist.

After the initial burst, a TV commercial by Ed McCabe and an elegant young art director, Ralph Ammirati, showed the air slowly leaking out of one of the ubiquitous ‘We try harder’ Avis balloons while the voice-over ran through the litany of Avis shortcomings. As the recitation nears its end, so does the air in the balloon, escaping with an increasingly irreverent farting noise. ‘Hertz regrets that we had to do this in public – but it had to be done.’

The same team, under the headline ‘Aha! You were expecting another get tough with Avis ad’, showed a smiling Hertz counter assistant patting a happy Avis girl who can’t see what the reader can – how cruelly she’s being patronised. Helmut Krone cited that specific ad as the beginning of the end for Avis and DDB. ‘Bernbach came in after McCabe’s first ad ran and threw The New York Times down on my desk: “Have you seen this? Don’t tell me how bad you think it is. As of today, they are alive – and we just died. What are you going to do about it?”.’

Good question. Hertz and Carl Ally had put them in a difficult position. Nothing that they were saying could be refuted, and retaliating would probably only turn what had been an engaging spectator sport into an undignified public squabble. DDB did try, with a couple of half-hearted ads. Ally replied just once and then, amid some accusation from the industry that it had become more about the two agencies yelling at each other than trying to shift a client’s product, Hertz moved on to a more assertive and positive campaign. DDB, too, abandoned ‘We try harder’ only 90 days after the Hertz campaign broke. After a change of ownership at Avis, they lost the account.

Oddly, both campaigns can justifiably claim success. For four years DDB had markedly improved Avis’s share, but then Hertz’s campaign froze their relative positions. Both campaigns had opened new ways in which companies could compete, not just in the market place, but in the media. For Carl Ally, Hertz confirmed the company in the same way that VW had confirmed DDB.

Carl Ally Inc was now properly established, a third front after DDB and PKL in the revolutionary war. It became another aspirational destination for creative people with new ideas. Stories of the wild and often lascivious behaviour of its paunchy, rumpled leader – Gargano can’t be certain he ever saw Ally with his shirt properly tucked in, no matter how elevated the occasion – delighted and appalled New York, possibly attracting creatives as much as the work.

HELAYNE SPIVAK, a secretary turned writer who eventually became creative director of Y&R, remembers being grabbed by Ally who happily ‘rammed his tongue down my throat, right there by my desk. The others must have taken him to one side and said, “Look Carl, you can’t go on like this and you’ve got to go and apologise to Helayne”.’

Carly Ally’s hugely successful campaign for Hertz; how to put down your smaller competitors without looking like a bully.

She giggles as she tells it. ‘So he came up to me and by way of apology – he did it again! I suppose I should have been upset but somehow, it didn’t really offend; it was Carl, I guess, it was just the way he was.’

Another secretary, Pat Sutula (later Langer), who also became a writer, remembers an all-staff memo from Ally announcing yet another party on some puny pretext. ‘It ended “I want you all there – remember, there’s still three of you I haven’t yet had”, and I thought, Oh my God, I’ve only been here three weeks, he must mean me!’

This is monstrous by today’s standards, but he carried it off. Even though the agency ended in fractiousness in the 1980s, affection for the man was enormous and lasted his lifetime. Marsha Cohen, who worked with him in the eighties, said, ‘He had a very distinctive flat, Midwestern accent, very noticeable to a New Yorker – he did not sound like the rest of us, that’s for sure. So even though he said irreverant things and cursed like a sailor… there was a little of the hick in him, which I think probably softened the expletives.’

His huge appetite for fun and adventure (he was never far from a party and never without an aircraft of some sort to fly himself to meetings whenever possible), and his passion for the work and for ‘his people’, endeared him to the staff.

One of the more radical ideas was the all-year-round four-day week, designed to give the staff longer leisure breaks. To reassure clients that their agency wasn’t slacking, it was policed vigorously and Ally insisted that people worked 36 hours minimum each week.

It started as an experiment, and when it was confirmed a T-shirt for the staff was produced featuring a sketch of Ally and the words, ‘First, Fridays Off. Now, Free Underwear’.

It’s difficult to imagine Reeves, Ogilvy or Bernbach doing that, or their staff being anything other than embarrassed by it. But it was so different at Carl Ally Inc.