“We’re being bought by McCann—do you know what that means?”

DON DRAPER TO PEGGY OLSEN MAD MEN

In a triumphalist piece in New York magazine Jerry Della Femina proclaimed the old-style agencies vanquished by the creative revolutionaries who were now carousing uninhibitedly up and down the Avenue. It actually appeared in the April 27, 1970, edition but one section could have been published at any time from the early sixties, with increasing accuracy as the decade went on.

“In a sense [clients of] the older agencies are asking for divorces, and then they’re running out with these young chicks. And so what the older agencies do is try to act like a woman who is trying to hold onto her husband.… The older agencies go out and buy a load of cosmetics and eyeshadow and they put all this stuff on and do their hair—this is what they’re doing when they start hiring freaky young kids at star salaries.” Della Femina should know—he’d only recently been the happy recipient of a handsome salary from Bates for exactly that reason.

The older agencies were fairly certain they knew what their clients wanted—more of what they’d been giving them for years. But even in the late fifties as Benton & Bowles demonstrated when they hired newer, edgier creative people like Amil Gargano and Ed McCabe, they were already looking over their shoulders at this strange new competition coming up on them. As the decade went on they thought they should have a few more exotic writers and art directors around to prevent their clients from flirting with the newer, sexier agencies.

JWT, still the largest agency, took it one stage further when in 1967 they lured Ron Rosenfeld away from DDB to be their creative director on a record $100,000 salary. It was a Judy Wald placement and widely recognized as a gamble; Lore Parker, still happily at DDB, said at the time, “It never seems to work for an old-line conservative agency to bring in DDB people to work under the old system. I am holding my breath to see what will happen with Ron Rosenfeld going to JWT.” She didn’t have to hold it for long. You can’t graft one culture onto another—unless there’s a massive upheaval, the existing culture will always squeeze out the interloper. Within eighteen months the experiment was over and Rosenfeld had left to set up his own agency with Len Sirowitz and Marion Harper—Harper, Rosenfeld, and Sirowitz.

BY MID-DECADE the gulf between Old and New had become a chasm. Bernbach’s style of advertising and of running an agency was either loved or loathed—there was no halfway point. Shorthanded as “Creative Advertising,” it was either the curse or the savior of the industry.

Driven by a combination of incomprehension and fear—and some justifiable concern as much of the new work was not conceived with the discipline of DDB’s creative department—the criticism came from those agencies too inert, and with clients too entrenched, to adapt.

Barton Cummings, President of Compton-Advertising, the major P&G agency responsible for some of the dreariest of Madison Avenue’s output, described it in Richard Gilbert’s Marching up Madison Avenue as as “The Museum of Modern Art School of Advertising” and accused it of wasting clients’ money. “What really produces sales is not art work but solid merchandising, research, and media spadework backed by straightforward, convincing advertising.” You can hear the quivering indignation.

The creative side, when it could be bothered, hit back. In a brilliant satire, Communication Arts magazine gravely demonstrated the “shortcomings” of DDB’s “Think Small” (see overleaf) and step by step systematically ruined it by showing how a Compton style agency would have “improved” the ad. It attracted at least one approving letter.

In business terms the “creative” agencies and the clients they represented were a tiny proportion of total advertising activity. Nevertheless, the noise within the trade was coming entirely from them. In 1965 when Mobil, at the time a major gasoline advertiser, took their business from Bates and gave it to DDB, it was perceived if not as the beginning of the end, at least the end of the beginning of the Creative Revolution, with the spoils going to the renegades.

At Bates, Reeves suddenly retired, claiming it had always been his intention to go at fifty-five. There’s some evidence to suggest that he was beginning to wonder whether he’d got it all entirely right after all. He confided to Ed McCabe that he felt “over positioned,” that he’d found himself, as a necessary business gambit, defending the tasteless work he’d secretly begun to hate.

Ogilvy & Mather (they’d dropped the Benson in 1964) was growing healthily but the agency’s reputation for interesting and original work was a fast-fading memory, stuck as they were with Ogilvy’s rigid and increasingly discredited rules.

BUT BIG WASN’T NECESSARILY all bad. Y&R had maintained a degree of creative integrity for several decades and flourished in the new atmosphere. They found the perfect creative leader for their times in Steve Frankfurt, an intelligent and articulate art director. Yet another student of Alexey Brodovitch and the Pratt Institute, Frankfurt’s initial experience had been in film, and he brought that to bear in his advertising career, approaching commercials in a less rigid way than had hitherto been attempted.

Most commercials shot by New York agencies in the fifties and early sixties were made by three major companies, with technicians and directors more used to shooting live commercials within sponsored programs. Many had limited experience of the wider aspects of filmmaking yet they controlled the business, treating the process like a factory production line, exercising minimum imagination and very little effort, while the creative teams were given almost no role in the execution of their ideas.

The revolutionizing of this system aided the larger Creative Revolution. Photographers who had previously been employed by agencies for stills shoots gradually began to be used by those same agencies for commercials. They brought a few advantages: they had already worked in color and were ready for its increasing presence in TV commercials throughout the sixties; they were used to the ways of the advertising system and understood the relationship between creative people and the account people, the agency and the client; and they were more prepared to cooperate.

At Carl Ally, Amil Gargano found the director that their agency producer had hired to shoot their first Volvo commercials patronizing, inflexible, and lacking in enthusiasm. He fired him after the first day and employed Mike Cuesta, a photographer he’d used before. It was the start of Cuesta’s career as a commercials director.

Irving Penn, Steve Horn, Bert Stern, and Harold Becker all trod the same path, while Bob Giraldi and George Gomes made the switch across from agency art director. Howard Zeiff, who’d shot stills for Levy’s and Polaroid for DDB in the fifties, became the most awarded and sought-after director of the late sixties. His reel by 1970 was a roll call of the absolute best of US advertising, stories told with exquisite timing and bathed in humanity; affectionate, realistic and always funny.

As an art director at Y&R, Frankfurt saw his commercials with an imaginative advertiser’s eye, asking for techniques and ideas that wouldn’t have occurred to the hidebound directors who were normally employed. A spot with no words at all was unheard of then but it didn’t stop Frankfurt; for Johnson & Johnson he shot a baby in close-up from the mother’s point of view rather than the conventional posed setup, making it more personal and emotional. He used stop-motion and borrowed from contemporary art—he saw no barriers to where you could go to make a commercial.

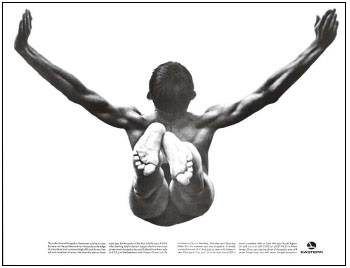

His talent and creative leadership skills earned him the presidency of the agency in 1967, unprecedented for an art director. Of all the agencies that predated DDB, Y&R under Frankfurt’s leadership was the only one to garner any respect from the new creative generation, with such work as their emotional Wings of Man campaign for Eastern Airlines. But in 1971, at the age of forty, he stepped down, later saying, “I never had a frustrating day in that company—until I became president.”

He went back to Hollywood to a new career in film publicity, back to his core skill as an art director. Amongst his subsequent output was the world-famous poster for Rosemary’s Baby.

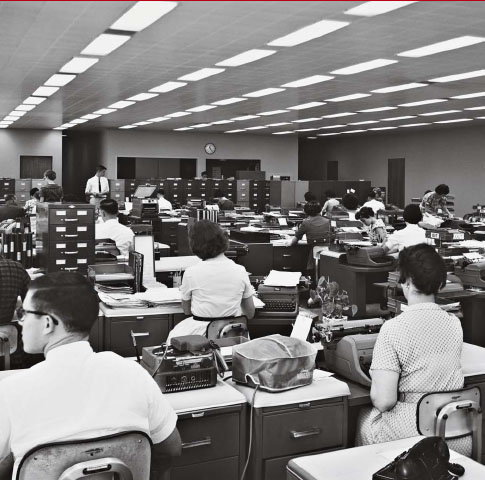

Back on Madison Avenue, according to a Newsweek article on the state of US advertising, in the first seven months of 1969 more than a hundred new agencies had started up. This is a little difficult to believe—that’s roughly two every three working days—but it does reflect the optimistic fervor with which the creative community regarded the business. As the article says, “Most of them have been the undertaking of one to four young creative people who have served a term with an old-line agency… who seek… the freedom to exercise their talents (and dress) as they wish.”

Their dress, in keeping with the times, had transformed since the day those sixteen Italian art directors lined up for their shoot. Newsweek reported the head of one of the leading agencies as saying, “You should see the things walking around back in our creative department. Frazzled hair, denims, neckerchiefs, the works.” Another said, “My God! We hired a new copywriter the other day—a very good one—and he came to work in his bare feet!” Fifteen years earlier Al Reis, a young account man at a Madison Avenue industrial agency, received a querulous all-staff memo from the president demanding that male staff wear knee-length socks so that no bare leg would show when they sat down.

Enthusiasm is one thing, foresight is another. Already there were signs that perhaps this “freedom to exercise their talents” was not all it appeared to be. PKL had already imploded, the partners barely speaking to each other. Koenig, by his own admission, was bored and absent a lot of the time, Lois was angry, and Papert was distracted by the demands of running what was now a public company. By 1967, Lois had left with Ron Holland to set up Lois Holland Callaway.

Further, the move to gain respectability and transparency by going public had apparently backfired; according to Papert, far from making the agency look respectable “PKL looked like it was doing better than P&G. They accused us of looking after ourselves rather than P&G.”

BUT NONE OF THIS turbulence had any effect on the one man whose ideas were light years away from the writers and art directors cavorting in their newfound freedoms. Marion Harper Jr. had set his sights on issues, both personal and professional, of truly immense consequence.

A campaign for Eastern Airlines, “The Wings of Man,” created by Steve Frankfurt at Young & Rubicam. This advertisement was on the author’s office wall in London in the late 1960s.

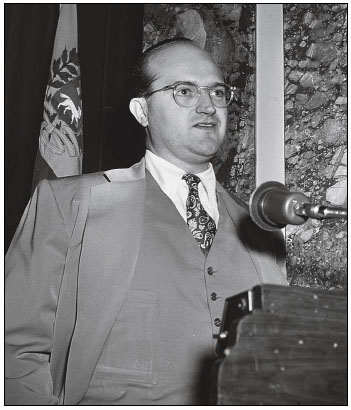

Harper joined McCann-Erickson, a large New York agency, in 1939 at the age of twenty-three as a trainee. Nine years later he was the president. That his trajectory through the ranks of what was a very conservative company was so rapid came as no surprise to those who knew of his phenomenal work ethic, focus, and intellect.

Born in Oklahama in 1916, his precocity was quickly obvious. At the age of ten he was addressing the United Daughters of the Confederacy in the Oklahoma State Capitol on his chosen subject, “The Time is Here for the North and South to Forget their Differences and Pull Together.” His mother, an occasional newspaper columnist who was both politically and socially aware, brought him up after his father, a newspaper space salesman, had left the family and moved to New York.

Harper worked diligently at school and after two years at Andover went to Yale, leaving in 1938 with top honors in math, economics, and psychology. His father, by then a vice president of General Foods, was an early believer in marketing and distribution research. It was a leaning that rubbed off on Marion; he’d worked his summer vacations as a door-to-door salesman, mainly of women’s goods, experimenting on the relative effectiveness of different sales pitches.

The following year he started in the postroom at McCann Erickson at 285 Madison Avenue. Hanging around the research department and asking endless questions laced with a few ideas of his own quickly got him promoted, and he was given his own research project to oversee, a method of testing ad copy prior to publication. He was mind-numbingly diligent in his analysis and by the age of twenty-six he was head of copy research, by thirty director of research, and by thirty-two, in 1948, president of McCann-Erickson.

By now he was married, with two children, not that he saw much of them—the next decade was outstanding for McCann and there’s no question that it was the result of Harper’s indefatigable effort. From fifth place in terms of agency size, with billings of $50 million, the company had a period of growth matched only by BBDO; by 1959 McCann Erickson was second only to JWT in size, billing $231 million.

He was personally quiet, “actually shy, a lonesome man, the company was his life,” says Carl Spielvogel, an executive who worked closely with him from 1960. But Harper’s moves were bold and unconventional. In 1958, in an almost unprecedented act, he resigned the Chrysler account for the smaller Buick business, believing that being on the GM roster represented the better opportunity for his agency’s growth. It wasn’t a popular move, but Harper’s judgement proved to be right.

He was careful, too, to nourish McCann’s already advanced global reach. Again, it was only JWT that could better McCann’s international client roster by 1960. One gain in particular was Coca-Cola, which became a flagship business for the agency. The agency won the account precisely because Coca Cola’s incumbent agency, D’Arcy, had shown no great enthusiasm to offer the overseas services that Coca-Cola needed and subsequently found at the vigorously global McCann.

In the business of the industry, Harper always seems to have been several steps ahead of everyone else. “He was a brilliant conceptualist. He could formulate ideas that took the industry quite a while to catch up with” says Spielvogel. He had a fearsome intellect, a ferocious work ethic, frequently putting in twenty-four-hour stretches, and phenomenal concentration. He would regularly astonish colleagues in new business presentations by displaying a detailed knowledge of the minutiae of, say, the prospective client’s regional market share or pricing policy, even though he’d been handed the fat briefing documents only two hours before the meeting.

TALL, BALD, AND HEAVY SET, this focus did not make Harper approachable, although it gained him respect; in a 1963 Time magazine article, an unnamed agency president said, “While I find Marion unattractively impersonal and ruthless, he does seem to be a marvelous organizer, and his mental capacity is immense.”

His capacity for innovative thinking was unending. Most of it seemed to come from a mind obsessed with research, especially with finding out what made things work and then implementing improved versions of them. He also had the ability to rise way above the daily grind; whilst being super-diligent about detail he would also be first with what we now call a “helicopter view.”

A lot of McCann’s appeal to clients was based around new and seductive research tools, encouraged by Harper. They were attracted to techniques with reassuringly technical names, such as the Relative Sales Conviction Test, which apparently guaranteed advertising success. How could you fail if your ads had been tested, for example, in The Perception Laboratory? This was a concept shown to him by a Dr. Eckhart Hess at the University of Chicago, which he adapted and modified to analyze responses to advertising by measuring the pupil dilation of interviewees while being shown various visual stimuli.

He was a seer; he is credited with being the first person to coin the term “think tank.” He was the first to describe the wider function of an ad agency as “marketing communications.” thirty years before the phrase became common usage. He arrived at the term partly because he was one of the first people to urge his staff to think beyond advertising on behalf of their clients. As early as 1960 he was talking about “holistic” answers to marketing problems (another industry buzzword thirty years later). He was enthusing about the coming “information explosion” and he had a prescient interest in computers. Many of these ideas came from the Institute of Communications Research, a McCann think tank to shape all the other think tanks, a department to improve the agency’s primary functions.

One notion, typical of the extraordinary breadth of his imagination and his fascination for the concept of the group thinking—together with his talent for packaging his ideas—was best described by Russ Johnston in his book, Marion Harper: An Unauthorized Biography, a riveting account of this intriguing man and his unusual story:

“He called it ‘The Humanivac’ a combination obviously of ‘Human’ and ‘Univac,’ as the then most popular computer was known. His idea was to assemble people like parts of a giant brain, each specializing in a particular aspect of marketing. A problem would be presented, each part of the human machine would go into action, and in a short time the solution would roll out, neatly packaged and ready to go to market. Some people thought it was fortunate that the idea slowly disappeared. Today [1982] it seems feasible but in 1962 it seemed pretty far-fetched. But, then, so was putting a man on the moon.”

His most obvious and publicly recognized goal was to overtake JWT in size. But a much later remark, talking about his aims at the time he was made president, reveals a much grander vision: “At thirty-eight… you can’t have as your ambition just to be the best of whatever there already is.” He was always going to do something different and new and the idea that changed not just McCann Erickson but the entire business out of all recognition was so devastatingly simple it seems incredible that advertising could have got so far without anyone having thought of it before. He invented the advertising conglomerate.

Marion Harper; a brilliant mind—but flawed.

THE IDEA WAS driven by clients’ deep abhorrence of sharing their advertising agent with any other client who could be conceived as a rival, no matter how remote. They claim it’s to preserve confidentiality, but the information passing through an advertising agency can rarely be more sensitive than that passing through auditors, corporate law firms, and banks—companies that rival clients are perfectly happy to share. Agencies comply because they have no choice but it means that none can ever handle more than one account in each category; one car, one toothpaste, one airline. (In Mad Men Sterling Cooper had to resign Mohawk Airlines to be free to pitch for American Airlines.)

So when one advertising agency acquired another, any conflict would have to be resolved, and usually this meant that the smaller of the conflicting accounts would be resigned. This immediately reduced the value of the merger, with two plus two often making no more than three.

Then Harper, in his words, “turned the management ladder sideways” and started a practice where the acquired agency would operate independently of the acquiring agency, but they would be financially bound by a holding company above them, the beneficiary of their joint profits. Ridiculously simple. But, amazingly, for advertising completely original.

There was a second dimension to the idea, one that has possibly had the greater reverberations through the business ever since. Harper figured that though agencies supplied clients with ancillary services like research, promotions advice and publicity, they never properly charged for them. Because they were located within the agency and were delivered largely by the same team who delivered their advertising, the client perception was that they weren’t a separate service and there should not be a significant fee for them.

So his idea was that specialist companies—Marplan, specializing in market research, Communications Counselors Inc. for publicity, and Sales Communications Inc. for sales promotions—should be set up to provide those services outside the agencies. Initially a number of their staff were actually the people who’d been doing those jobs within the agencies—no matter, their specific expertise and experience would be properly and separately charged for, and their profits would go to the holding company. Economies of scale would be achieved by having as much common backroom staff to service the agencies and specialist companies as possible—administration, purchasing, finance—located in the holding company.

The holding company therefore sat on top of a variety of independently operating and competing advertising agencies, each of which could cross-refer business to a variety of equally independent specialist support service companies. Extend this overseas, float it on the stockmarket and you have the prototype of the contemporary marketing services conglomerate like WPP or Omnicom.

Though Harper himself described what he was creating as a “revolution,” it was far from the Creative Revolution over at DDB. Indeed, he had as great a suspicion of it as Bart Cummings, attacking in a major management meeting “the new cult of creativity… closely identified with the bizarre.” He was poles apart from Bernbach, whose comment, “I warn you against believing advertising is a science” was in flat contradiction of everything Harper believed. He wasn’t neglectful of the creative side but, typically, he viewed it as yet another area that would benefit from the analytical and think-tank-based approach—and he set up yet another Interpublic subsidiary company.

Spielvogel describes it as “a sort of combination of think tank and creative center. It was thinking out how the projects should go creatively, and then turning over the grunt work, the media and development of the creative work, to the agency. Harper called it ‘co-creativity’—what happens when you blend different skills at a very high level. We’re conducting an experiment to learn whether through co-creativity you can produce better, neater, brighter, hotter, more creatively.”

It was to be called Jack Tinker & Partners, the partners element indicating that each of the four members (Jack Tinker, an art director; Dr. Herta Herzog, an Austrian psychologist expert in motivational research; Don Calhoun, a copywriter; and Myron McDonald, the marketing director) had an equal voice.

BORN IN PITTSBURGH, Tinker had made his way up through the ranks as an art director until the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. He tried to enlist, saying in a 1982 interview: “I sat there for two days in my underwear and eventually somebody examined me and I passed and the last question was ‘Where did you go to college?’, and I said, ‘Well, I didn’t go to college. I went to this art school.’ As soon as I said that the noncommissioned officer, whoever he was, said, ‘That’s all. Put your pants on and get out.’”

Tinker went briefly to JWT but McCann got him back as creative director. In the latter years of the fifties he’d been somewhat sidelined—one curious feature of Harper’s casting for Jack Tinker & Partners was that all four of the partners had been left out of the mainstream of agency operations.

The agency started off in the Waldorf Towers in 1964 but they didn’t last long there—the comings and goings of clients, messenger boys, deliveries and all the noisy circus of office life alerted their classy neighbors—General Douglas MacArthur on the floor below, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor above. The terms of the lease forbidding use of the premises for business were enforced and they were out on their collective ear. They moved to a suite in the Dorset Hotel, previously owned by Martin Revson, the owner of Revlon cosmetics. They weren’t exactly slumming it. Charlie Moss, a young writer who’d been hired by Tinker from DDB on more than double his previous salary, describes the scene:

“It was really a Mad Men set—the main room was two stories high with a kind of a balcony round the top, everything was white, the furniture was white with a white baby grand piano in the middle of the room. Around this big central conference room and living room place were other offices, which were hotel suites/rooms. When we came in they said they didn’t have any more room on that floor, so they put us on a different floor. They gave us a suite of a living room and two bedrooms that were our office, no furniture, just a carpet. The first three weeks we did everything on the floor.”

Who did what is not clear, but judged against Harper’s initial brief there was some success. “The first piece of business we had was [from] the Bulova Watch Company… although when we got it, it was a piece of machinery that had been a spin off from the Space Program,” recalls Jack Tinker. The agency helped Bulova decide how to use it, then designed and named it—The Accutron Watch—and helped them get it into shops like Abercrombie & Fitch, a very different sort of store from the A&F of today.

Next they helped with the design, naming, and styling of the Buick Riviera, followed by projects for Coca-Cola, Exxon, product design for Westinghouse, and providing input for Interpublic new business presentations. Then they took on a project for their first direct client, Miles Laboratories, and their success with it changed the nature of the organization completely.

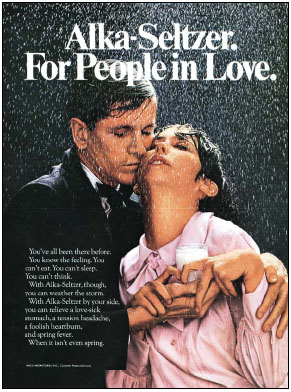

The Alka Seltzer account had been won in comical circumstances; Miles didn’t want it known that their account was loose, and Harper and his team had flown to their headquarters at Elkhart, Indiana, in his eccentric corporate aeroplane, a converted bomber. While the meeting was underway the plane was backed into fresh concrete at a dispersal area at the airport. Their attempt at discretion was blown as the local newspaper the next day ran the story of the Interpublic plane conspicuously sunk in cement.

The advertising idea could not have been simpler: as the male voice-over says, “No matter what shape your stomach’s in… when it gets out of shape… take Alka Seltzer,” and accompanying it we see a series of stomachs—flat, fat, and flabby—shown in close-up in everyday use: a road digger, a ballet dancer, a fat man having his stomach jabbed by another man with whom he is in urgent conversation, and a mechanic easing himself under a car. Under Howard Zieff’s sympathetic direction the campaign was warm, affectionate and infectious, and the jaunty tune written by Sascha Burland, which reached number thirteen in the Billboard chart, helped delight the United States and revitalize Alka Seltzer.

The campaign was so unlike anything ever seen for a pharmaceutical product before. The follow-up was animated, a cartoon man berated by his stomach (played by Gene Wilder), complaining about the rich food he eats. The dialogue is fast and witty, like a Woody Allen exchange. And with the strap line “When you and your stomach don’t agree” the viewer was again charmed by a commercial in a category in which they were more used to being bullied by Rosser Reeves’ doctors in lab coats and crashing hammers in animated heads.

The industry acclaim for the campaign changed the perception of Jack Tinker & Partners from an experimental creative think tank to that of a full-fledged creative hot shop. Indeed, history now portrays Harper’s motive as being much like those agencies that Della Femina lambasted in his article, setting it up as a satellite for more adventurous clients who may have thought of leaving the unadventurous McCann. But Harper came to regret letting Tinker take the business as their own client, rather than continuing to work on a project basis only: “I should have continued some immediate provision for experimental creative principles. Because what happened was that the client began to eat up the people.”

In the same interview he credited Dr. Herzog (the model for Dr. Greta Guttman, the European research director at Sterling Cooper who enraged Draper with her recommendations for Lucky Strike advertising) with the simple suggestion that two rather than one Alka Seltzer tablets was required. The result? Double the sales!

TINKER WAS PROVING to be yet another successful addition to Harper’s new and burgeoning group. The first acquisition had been Marschalk and Pratt in 1954, an agency with which McCann shared the Standard Oil—Exxon—business. Amongst others added to the mix over the coming years were the New York and London offices of Pritchard Wood, a British agency, and Erwin Wasey. Initially the agencies and ancillary companies were owned by McCann but operated entirely autonomously. The final move was to take the name of a public relations company McCann owned in Germany, Interpublic—easy to say, spell and understand in any country—and incorporate it as the holding company for Harper’s empire in 1961. Flotation wasn’t to happen for another ten years but meanwhile, all was going well for the “emperor”—except that increasingly his courtiers were beginning to wonder whether he was wearing any clothes.

“Marion was always more interested in the top line than the bottom line,” says Spielvogel. Harper had employed him personally in 1960 from writing his daily advertising column for the New York Times as his executive assistant, specifically to work on the establishment of Interpublic. He did well, and by 1967 was vice president and on the main board of Interpublic, handling the Miller Beer account and responsible for new business acquisition and press relations.

Part of the famous Alka Seltzer campaign in the sixties, by Jack Tinker & Partners.

Looking back, he says of Harper, “When he was building the company he was a brilliant business conceptualist and then he became enamored with growth at any price. And there was a big price to pay.”

Harper’s operating style, both professional and personal, was becoming increasingly grand and expansive. His emphasis on internal training and education for his staff in the latest techniques and procedures cost huge sums in the enormous and elaborate global meetings that he would stage. The chase for new business was relentless and he had no interest in keeping down the costs for pitches.

In less than four days in 1965, for a $10 million piece of GM business, he had fifty copies of a detailed presentation written and printed in full quality hard back book form. Says Russ Johnston, “The cost… must have been enormous. The craftsmen were union workers and the plate making, typesetting, printing and binding were done on a weekend overtime basis.” Johnston estimates the cost of an equally unsuccessful pitch for TWA in 1967 at more than $200,000.

The balances that had kept him in check had fallen away; Harry McCann, the man who had employed and guided him in his early years, had long since retired and subsequently been killed in a car crash. And the long-term chief financial officer Burt Stilson, suffered a heart attack and retired to Florida to play golf.

“A lot of people who reach a certain point start to smell the roses,” said one contemporary observer. Harper’s personal life, too, was becoming stratospherically high octane. Bizarrely, he invested heavily and unwisely in prize cattle, and for his second wife, Valerie Feit (“long legged, radiant, beautiful,” according to Russ Johnston), he set up a fashion consultancy in Paris under the Interpublic banner. It was a loss maker.

His most public vice was the acquisition of corporate aircraft, ridiculed across Madison Avenue as Harper’s Airforce. He capped them all in 1965 with the purchase of a DC7 from KLM. Seating more than 150 people, it was as pointless an acquisition as it was expensive. After several months of conversion, it emerged with a state-of-the-art office and a drawing room with brass standard lamps, gold deep-pile rugs, a sumptuous sofa in glove leather, Eames chairs and silk wall coverings. The bedroom had a full-size bed and tiled shower, while the galley was equipped to prepare and serve full candlelight dinners. Full movie-projection facilities were laid on.

At least Harper made full use of it. Over one weekend he flew two senior creative people to Paris and back to give them a pep talk. Often the use was entirely personal, like when it was flown to Mexico to pick up antique furniture. And perhaps the one flight that was most symbolic of the impending disaster was when he used it to fly Valerie to France—on the day he was supposed to be in court on alleged tax offences.

Some of this could perhaps be tolerated if the company was performing, but the figures were ceasing to add up. At one time the organization employed 8,300 people worldwide with global billings of $711 million. But this growth by acquisition was hiding stagnation in trading. Neil Gilliatt, an account man and vice chairman in 1964 could remember “there were years in which the earnings on the Coca-Cola account were two or three times greater than the earnings of the total corporation.”

Although the separation of the agencies allowed competing clients, there were some who still wouldn’t play. The acquisition of Waseys with its Carnation business cost McCann’s Nestlé, and McCann suffered again when Continental walked because of Jack Tinker taking on Braniff.

INCREASINGLY, HARPER WAS PUSHING the limits. Spielvogel had by now succeeded Stilson as one of the three trustees of the voting shares, along with Bob Healy and Harper. He remembers consulting a lawyer about an idea for the pension plan Harper had asked him to implement. “You do that Mr. Spielvogel,” said the lawyer evenly, “and you see the stripes you’re wearing on that suit? They’ll be going the other way.”

Harper wouldn’t be told—he didn’t believe he could fail. It all came to a head in 1967 when Irving Trust, worried by the balance sheet, called in a loan. Spielvogel, however, wasn’t immediately worried. He had been advised by a financial mentor that the last thing banks wanted was to own any company, least of all a big advertising agency.

“So on that given day, on the fortieth floor of the TimeLife Building, Bob Healy and I were sitting there waiting for these four people from the Irving Trust who came in looking like four morticians and they said, ‘We’ve very bad news for you. We’re calling your loans’, and I said ‘Fine’, and took out this big set of fake keys and put them on the table and we started to walk out. The lead banker said, ‘Woah, where are you going?’ and I said, ‘You now own the largest advertising agency’. And he said, ‘No, no, I’m sure we can work this out.’” They bought time from Irving Trust but with one condition—that Harper be removed from the chief executive position.

At promptly 10:00 AM on Thursday, November 9, 1967, a board meeting was called to order. Harper didn’t seem to know what was about to hit him. He opened the meeting in the normal way but was quickly interrupted. The position of Irving Trust was outlined and Harper, puzzled but still apparently confident, put it to the vote.

All six men wordlessly voted against him. He paused for a moment and then, without saying a word, left the room.

Healy was installed as CEO, with Harper as chairman, but the board knew that their time with Irving Trust was limited. Arrangements were made with Chase Manhattan to refinance the agency but they in turn stipulated that Harper must go altogether. It was over.

Three clients, Coca-Cola, Heublien and Carnation, advanced $5 million in billings in a warming show of support and confidence. Within six months the business was in good shape.

Harper himself made two attempts to carry on in the business, the one at Harper, Rosenfeld & Sirowitz as a sort of Jack Tinker reincarnation, and the other as a marketing consultant. Neither worked out and he literally disappeared off the scene. Stories of tax fraud swirled around but nothing ever came to a head.

There is a strange Howard Hughes-like postscript to this story. In 1979, an Advertising Age reporter, John Revett, went down to Oklahoma City to see Harper’s mother in an attempt to locate and possibly interview him. They were chatting away when a tall man walked into the room, asked who the interloper was and identified himself.

“I’m Marion Harper.”

He didn’t want to discuss the past.