“Be a woman. It’s a powerful business when done correctly.”

BOBBIE BARRETT TO PEGGY OLSEN MAD MEN

Twenty-four-year-old Mary Moore, “all hair, and legs for miles,” keen and fresh from a night course at the School of Visual Arts, sat in front of a senior art director who was looking for an assistant. She’d borrowed clothes for the interview from a colleague at the bank where she worked but had tried them on only that morning: “They were so tight. It was salacious. Every curve. And I had a nice coat so I thought I’m not going to take it off. I had a little rehearsal: ‘Would you like to take your coat off?’ ‘No I’m a little chilly, I’ll keep it on.’ So that’s what I did. And then he said, ‘I wanna see what you look like. Stand up, do a twirl.’ It was a strange feeling. I didn’t know any better. I hadn’t heard the drill—you don’t do that. I knew this wasn’t exactly right, but I couldn’t imagine saying no. I figured maybe he was entitled to look at his employees.”

It’s a common story, right across the business—nothing physical but a casual sexism, low key harassment. Carl Ally openly encouraged intra-office flirting and relationships in the belief that it kept up interest levels in life at the agency—and thus attendance. Jerry Della Femina later shared that view, running his agency like a frat house with a lot of lusty males running around in lewd good humor.

“The men in those days took a lot of liberties with women: ‘Look at the buns on that one,’ ‘Look at the chest on that one,’ very blatant,” says Mary Leigh Weiss who worked at the Hooper Research organization. “You weren’t offended, you were flattered. That’s how it was in those days. Everyone wanted to be noticed by men, and they noticed you and you were flattered.”

Not every woman would have agreed with that, but at the same time there’s less rancor or bitterness about the gender attitudes than may be expected. According to Della Femina, the women were just as enthusiastic about the annual Sex Contest as the men. As Mary Moore says of what would now be seen as her utter humiliation that day, “I didn’t go home in tears about it.” It wasn’t until 1963 that Betty Freidan’s The Feminine Mystique was published and the awakening of consciousness amongst women started the long push for change.

When you talk about it now, most of the men will grin, albeit a little sheepishly, and the women just shrug, both sexes sometimes with a little gleam in the eye. Mary Moore remembers, “As I know, nobody nailed you in the ladies’ room but there was a lot of talk about it and you constantly had to giggle.” As one former secretary said, “It was just the way it was.”

The overwhelming majority of the females available for flirtation were support staff, secretaries, and admin people. As with any minority group in advertising, no matter how enlightened the employment policy of any agency, it could move only at the pace of its clients, some of whom in the sixties were still specifying no Jews. And despite more than 50 percent of advertising always having been aimed at women, with a conservative, male-dominated client community it’s difficult to find many reports of women account executives before 1960. Fashion and cosmetic accounts may have had the occasional female client and so occasionally an agency would employ a woman to work with her.

EVEN IN THE 1960s female account executives were few and far between, and it probably wasn’t an appealing job for women anyway, the prevailing service culture generally involving hard drinking and racy entertainment. But this affected the creative people less as the clients didn’t have to meet them or socialize with them.

There had always been female copywriters, even back in the nineteenth century; their three regular routes into the copy department were through a job writing for the vast number and variety of women’s magazines, through an in-house writing job at a retail store, or starting as an agency secretary and transferring.

Even back in 1910 JWT had a women’s unit, staffed by women copywriters headed by Helen Landsdowne. She had formidable talents, in writing, in business, and socially. In 1911 she wrote an ad for Woodbury’s facial soap that both shocked and thrilled and is generally reckoned to represent the beginning of sex appeal in selling, with its visual of a man and a woman in close proximity, and the line “The skin you love to touch.” She was a prominent suffragette and having married Stanley Resor, with whom she bought JWT from Commodore Thompson himself, became energetic in furthering the interests of women in business from a powerful position at the very top of the largest agency in the United States.

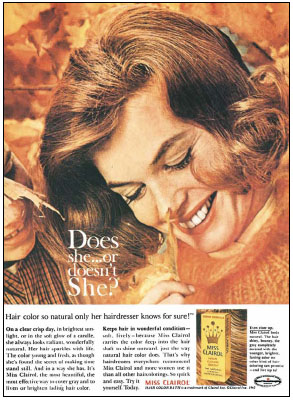

Bernice Fitzgibbon worked at Macy’s from 1926 until 1940, when she moved to Gimbels where she ran their advertising department until 1954, with a significant number of female agency writers of the fifties and sixties passing through her department. Shirley Polyakoff at FCB, one of a growing group of female copy chiefs and creative directors, gained national fame as the writer of “Does she or doesn’t she?”, the phenomenally successful Clairol hair colorant ad that raised eyebrows because of its sexual innuendo. Jane Trahey, a copywriter, started her own agency in 1960, a business and financial, if not high-profile, success. And for a while the DDB creative department under Phyllis Robinson had more women than men.

Women were particularly well represented in research departments but, apart from copywriting and the traditional areas of secretarial and clerical roles, there were very few other posts held by women. Even in art direction, a job for which gender should have been no more an issue than copywriting, women were almost nonexistent. As he recalls waiting for his interview at Benton & Bowles reception in 1961, Amil Gargano describes, “A young woman with long dark hair and brown eyes passed in front of me without glancing up from the paper she was reading. She was one of the most beautiful women I had ever seen.” She was Elaine Parfundi and he’s seen her more or less every day since as they married in December 1963. She was then the only female art director at Benton & Bowles and when she left six years later there was still only one other there.

The advertisement for Clairol by Shirley Polyakoff at Foote, Cone & Belding, created in 1957.

In the mid–1950s, Joy Golden was in the steno pool at BBDO with forty other girls, on $40 a week, with a supervisor walking up and down and all the typing you could handle. But in her lunchtime, just like Bill Bernbach years before at Schenley’s, she decided to have a go at improving the ads she saw in The Ladies’ Home Journal.

She wandered around the management floor with a sheaf of her ideas, looking for someone to show them to. Eventually she found Jean Rindlaub, a copy chief who liked what she saw and took Joy on as a copywriter. It was her first step on a lifetime career in the business, culminating with her own radio production company in the 1980s. Peggy Olsen’s path in Mad Men had been trodden many times before by women like Joy.

HOWEVER GOOD THEY WERE at their jobs, women in any discipline at any level couldn’t escape unequal treatment, some of it bizarre. According to advertising columnist Barbara Lippert, up until the sixties women working at BBDO weren’t allowed in the executive dining room—a couple of senior female copywriters enjoyed the regal privilege of being served the meal at their desks from a silver cart by a maid in full uniform.

Attitudes to clothing and appearance too were still often deeply conservative. Joelle Anderson, in the research department at Grey, found it a pretty relaxed atmosphere but people were shocked, “even agog about it” when her group leader turned up in a pant suit one day. Even at Carl Ally, liberated and modish as it was, Ally saw fit to send an all staff memo after one of his female staff wore pants to the office, saying, “I look askance, at girls who wear pants.” Three days later he cheerfully rescinded it when, as Pat Langer says, “He realized you could see more of a slim woman’s shape in tight fitting pants than in a skirt.”

The worst inequalities were in both prospects and salary. There was an automatic assumption, discussed but rarely fought against, that women would get less money than their male equivalents. Mary Moore had a boyfriend, an art director, working at the same agency as her: “We used to talk about how we wanted to leave and get better jobs. He said, ‘You’re terrific, you ought to be making $12,000, and I ought to be making $14,000.’”

As for promotion to senior executive level, again apart from copywriting or research, the glass ceiling was so obvious it might as well have been iron. By 1960, McCann-Erickson, led by a comparatively woman friendly Marion Harper, had only six female vice presidents out of a total of a hundred. No agency was led by a woman unless it was started by her. And JWT, once prominent in promoting women, didn’t appoint their first female senior vice president until 1973.

None of this was the slightest deterrent to Mary Wells, a determined, stylish, brown-eyed, female writer who, as George Lois said, “You could tell would never end up with wrinkles in a writer’s tower.”

Her 1967 response to suggestions of discrimination was typically robust; despite the blatant evidence all around her, she pronounced, “The idea about American men trying to keep women down in business is a bunch of hogwash. I’ve never been discriminated against in my life, and I think the women who have experienced it would have anyway—no matter if they were men, or cows, or what have you. Only the ‘nuts and the kooks’ are screaming like babies.”

While successful women are under no compulsion to campaign on behalf of their fellow women, it’s also probably not necessary to dump on them quite so heavily. Amelia Bassin, formerly advertising director of Fabergé, hit back in the speech she made as the American Advertising Federation’s newly elected Advertising Woman of the Year in 1970: “I can well believe Miss Mary never got discriminated against. There is no privileged class in the world to compare with that of the beautiful woman.… It’s difficult to tell if success has spoiled Mary Wells; but boy, is she ever spoiling success.”

But what success. No advertising woman, before or since, has ever gone so far and traveled so fast as Mary Wells Lawrence.

SHE CAME TO NEW YORK as eighteen-year-old Mary Berg from her native Youngstown, Ohio, in 1947 with hopes of being an actress. She didn’t get anywhere and slipped into advertising through the traditional route for female writers—a job in the publicity department at a store, in her case Macy’s. From there she was briefly at McCann-Erickson and then Lennen & Newell where she coincided briefly for the first time with Lois. By now she was Mary Wells—but more usually Bunny Wells—married to an art director at OB&M, Bert Wells.

With her knowledge of the fashion industry and her exquisite sense of style, an asset which was to be of immeasurable use to her later and shaped much of what she achieved, she was hired by Phyllis Robinson at DDB on fashion business. Diligence and determination got her to group head status and she also earned respect as a writer. It was she who was largely responsible for the evocative French tourism campaign for which she’d been on extensive visits to France, starting a love affair with Europe that’s lasted throughout her life.

She was completely at home at the creative Mecca of DDB when, in 1963, a call came out of the blue from Jack Tinker to join her at his think tank. Wells arrived before the Alka Seltzer win, when the agency was performing well as an ideas generator but with an unspectacular reputation and image. Tinker and Harper felt that she was the person to liven it up.

Tinker had already hired an art director, Stewart Green, who Wells linked up with a writer she brought from DDB, Dick Rich, and it was these two she led in the Alka Seltzer project. With its immediate and enormous success, Harper and Tinker’s appointment of Wells had quickly been vindicated.

There is no question that she was a terrific choice; unphased by traditional ways of doing business, she set about regenerating the agency, hiring a stream of A-list creative people and paying them well over the rate to get the place buzzing and talked about.

One of Wells’ many insights was the recognition that there were more impactful ways of gaining publicity than schmoozing the trade press at 21. As Mad Men’s Don Draper said, “If you don’t like the conversation, change it.” She had a fantastic talent on behalf of her clients, her agency, and herself of getting people to talk about the things she wanted talked about.

It helped that she was petite, highly attractive, witty, and articulate. Both men and women when describing her will almost inevitably refer to her “great legs.” Her style for that time was more European than American, she dressed with French chic and to English ears there is a slight Englishness to her accent—not the ersatz English of someone trying too hard but the refined, cultured note reminiscent of Grace Kelly, a woman with whom, coincidentally, she was to become great friends.

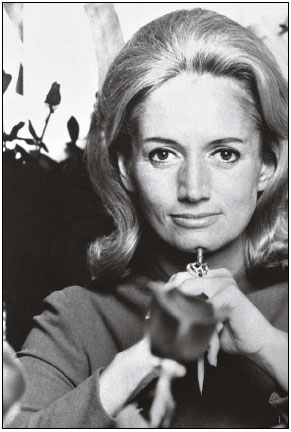

Mary Wells Lawrence in 1970, the founder of Wells Rich Greene, the largest agency run by a woman at the time.

Ken Roman recalls a speech she gave at the Harvard Business School Club when she had become president of her own agency. “We’d never seen a president, a female president of an agency. So there’s all these MBAs sitting there and she gets up, she’s in a smartly tailored suit and she looked so sophisticated. And they’re waiting to see what happens. And she had a scarf on, and she slowly took off the scarf, smiled, and said, ‘And that’s all I’m going to take off’. It was so perfect. She had show business.”

She had massive energy. While cool and sophisticated, she was not above masculine rough-and-tumble and was surrounded by a praetorian guard of young, male creative people who were dazzled by her. It’s unquestionable she hypnotized people, male and female. There are colleagues from the 1960s who are still enthralled by her, and have massive respect and admiration for her—although affection is a little less evident. There’s even a little whiff of fear. Getting people to talk about her even now is a little like asking around for information on a mafia Don: John will speak if Jill goes first. “Tell me what Jack says and I’ll tell you if I agree with him.” “Don’t ask me about that, ask Joan.”

Rumors of both random kindness and random ruthlessness circulate equally. One story, unconfirmed, placed her in her office late one afternoon, where she had summoned a creative team, while her make-up artist prepared her for an evening function. With her back to the team, she fired them through the reflection in her mirror.

Time and again you’re told she was a marketing genius, that she had the most extraordinary insights into the minds of the consumer, no matter who or for what product. When later she won American Motors, the male creative staff couldn’t wait to get their hands oily, believing that a car, and a fairly downmarket car at that, was not something Mary would understand. But within days of getting the assignment, she’d given them a detailed rundown of every model and its potential role in possible buyers’ lives. Apparently, she was spot on.

NEXT FOR WELLS at Jack Tinker was another of those lucky bounces that seem to preface so many great breakthroughs. In a trip to the west coast to court Continental airlines, their executive vice president, Harding Lawrence, confided to Wells that he was about to leave to head up a little-known Texas airline, Braniff, and he’d rather Tinker saved themselves for that account. This led to one of the most famous airline campaigns of all time—and certainly the making of Mary Wells, in both creative and business terms.

Braniff had plenty of lucrative routes, particularly to Central and South America, but almost no awareness. And Lawrence had big ideas, including immediate investment in a new fleet, and thus an urgent need to sell seats, which could only be brought about by instant fame.

This is where Wells’ superlative sense of not just style but the application of style came in. An airline is an airline—they fly the same planes, seat you in the same seats, serve the same food. And, as she noticed, they did it in a utilitarian, almost military style. These were the early days of the jet age, before flying became packagable as romantic. Indeed, as DDB had noted with El Al, most airline advertising tended to be little more than timetable publication—there wasn’t much else to say. Y&R hadn’t even started their emotional Wings of Man campaign for Eastern Airlines.

In her 2002 autobiography A Big Life (in Advertising), Wells described her epiphany one morning when standing in a check-in line at Chicago airport. “Airlines had developed out of the military… planes were metallic or white with a stripe painted down the middle to make them look as if they could get up and fly. The terminals were greige. They had off-white walls, cheap stone or linoleum floors, grey metal benches, there were tacky signs stuck into walls… Stewardesses, as they were called, were dressed to look like nurses.… There were no interesting ideas, no place for your eyes to rest, nothing smart anywhere.”

Color. That was the answer. Vibrant, raging, scintillating, Braniff planes would be like brilliant flying jewels, like no planes you’d ever seen before, each painted in a different vivid color. The fabrics would dazzle and the stewardesses would dress in the most outrageous outfits. Alexander Girard was hired to design the interiors, Emilio Pucci to create the outfits for the stewardesses—or hostesses as Braniff now called them. A flight on Braniff was to be a party. Ideas on ticketing, seating, and entertainment came thick and fast. Turning a flight into a fashion parade, the stewardesses would change their outfits four times on the longer routes.

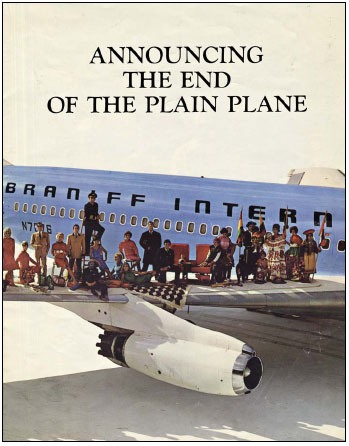

It was, as the launch print ad said, “The End of the Plain Plane.” Created by writer Charlie Moss and art director Phil Parker, the line was printed under a picture of air hostesses and flight crew standing like a flock of brilliantly colored exotic birds on the wing of a vivid blue Braniff 720. The payoff to the copy was perfect, it could have been another headline: “We won’t get you there any faster—but it’ll seem that way.”

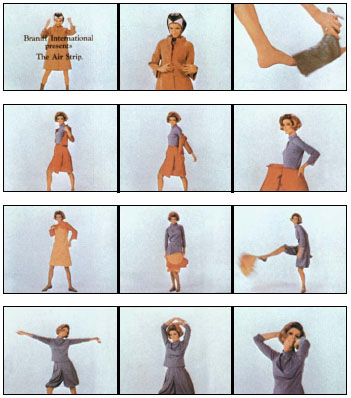

The commercial was a kaleidoscopic view of the preparation for the print ad photo shoot, with the movements of the various people getting into position choreographed for maximum vivacity. Others followed, one announcing the stewardesses’ changes of costume as “The Air Strip.”

The launch was a wild success. Five Braniff planes—blue, green, yellow, red, and turquoise—flew low and slow past a grandstand at Dallas airport filled with three hundred press from around the world. Acclaim followed from the passengers. To Wells’ delight there were reports of people playing the game, trying to book tickets on the basis of the color of plane they might fly on, going for the full set of seven. Acclaim also followed from the advertising business.

The campaign was well underway when Wells dropped a bombshell on Tinker and Harper; she resigned in order to set up on her own agency. She had been given her first real taste of authority and autonomy, and Tinker was never going to confine her for long after that—there’s a huge and heady difference between being one of many creative group heads within a large creative department, as she had been, and being the charismatic leader of a “hot” agency, as she’d now experienced.

How it came about is confused by several differing reports. In her autobiography Wells says she was furious because Harper reneged on a deal to make her president—a deal which curiously she hadn’t previously noted in the book, but if had been made it was presumably offered as a lure to get her to join in the first place. Tinker, on the other hand, says she came to him suggesting they try to buy the agency out of Interpublic. He put a deal to Harper which was refused and, sensing she wouldn’t stay much longer anyway, he agreed that she should set up her own company. Yet another version has Harper offering her the presidency but he was blocked by Hertzog and Myron McDonald, who said they would never work for her, and so she felt she had to leave. What is fact, however, is that through Carl Spielvogel, Harper offered her a contract worth $1 million over ten years, a quite phenomenal deal for 1966.

‘The End of the Plain Plane’; in 1965 the Braniff image was completely reinvented by Mary Wells, Alexander Girard and Emilio Pucci.

Further examples from the Braniff campaign, including the “The Air Strip.” Originally there were eight different colors for the aircraft but lavender when combined with white and black is bad luck in Mexico and South America, so the color scheme was dropped to seven.

With some courage she refused the offer. With Dick Rich, Stew Greene, and, critically, the Branifff account, and actively encouraged by Harding Lawrence, who she would marry the next year, she set up Wells Rich Greene (WRG) in the Gotham Hotel in April 1966.

OF THE SUBSEQUENT SUCCESS, just a few figures need to be grasped. She started with the $6 million billing from Braniff, a loan from Chemical Bank and a handful of employees in four rooms at the Gotham, including her mother answering the phone. By the end of the first year her agency, now at 575 Madison Avenue, billed $35 million, and had a hundred employees. Within five years, WRG was billing $100 million with five offices, two of them overseas. Allowing for inflation, no stand alone start-up agency has ever exceeded that rate of growth. By 1969 Wells was paying herself $250,000 per year, a salary higher than anyone else in US advertising, man or woman. And when she took the company public in 1968, she became the first ever female CEO of a quoted company of any sort in US history.

And to remind ourselves just how far we’ve come in this story, the agency principles were a woman and two Jews—and all three creative people.

Divorced from Bert Wells as she started at Tinker, she married Harding Lawrence in Paris in 1967, a close marriage that lasted until his death in 2002. Typical of Wells was the exclusivity and originality of her wedding outfits. In the middle of this phenomenally demanding period she’d had time to spot Halston, a hat designer for Bergdorf Goodman, and asked him to design a green velvet wedding dress—green was a popular color with her. It was the first dress he ever sold. For the night before the wedding she wore a black ruffled and flounced organza creation made for her by Hubert de Givenchy. Style, always style.

Contributing to the agency’s growth was the win of American Motors, some P&G business, and TWA, which she won after agreeing with her husband to drop Braniff. That account went to George Lois’s new agency, Lois Holland Calloway, where he created the campaign “If you’ve got it, flaunt it,” featuring amongst other commercials Andy Warhol explaining the finer points of his art to an impassive Sony Liston seated next to him on a Braniff flight.

Wells’ first successful account was the return of an old friend, Alka Seltzer, which also boosted the billings. They had moved to DDB shortly after Wells, Rich, and Greene’s breakaway from Tinker, triggering its sad implosion. DDB had given Alka Seltzer more wonderfully entertaining and memorable advertising but in the view of Miles Laboratories it was ineffective and too costly; DDB was insisting on sixty-second spots and the client wanted thirty seconds to double their exposure. They called Mary, and she gave them the thirty-second media schedule they wanted. She also gave them yet another string of memorable commercials: “Try it, you’ll like it” and “I can’t believe I ate the whole thing,” both of which slogans passed into the national vernacular.

One of the earliest WRG gains was in the increasingly controversial category of tobacco. The advertising business had the same problem as government with what was now confirmed as a killer product; there was just too much money in it to walk away. And money brought exposure and thus possible fame for the agency’s work. The Marlboro Cowboy, first run in 1955, had helped put Chicago’s Leo Burnett on the national map. While some, like DDB and Carl Ally, refused to work on the deadly weed, Wells took the view that if it was permissible to sell it, it should be permissible to advertise it. Anything else was hypocrisy, “un-American” as she put it.

Philip Morris offered them Benson and Hedges 100s, a cigarette that was longer than king-size. They were expecting something cool and image-based, probably visual metaphors to do with longer slimmer objects—aircraft, skyscrapers, or, as they put it, long legs accentuated by mini skirts.

Once in front of their layout pads Rich and Greene agreed the brief was drivel and came up with an idea that couldn’t have been sweeter or further away from Philip Morris’ expectations: the disadvantages of the Benson and Hedges 100s. Like the Alka Seltzer “Stomachs” it was a series of close-ups, this time of people failing to come to grips with the extra length of the cigarette while smoking it. One man gets his jammed in an elevator door; another sets fire to the beard of the man he’s talking to; one tries to light his two thirds of the way up; and in yet another we see a man’s face obscured by the newspaper he’s reading—a hole is slowly burnt in the page as his cigarette smolders its way through. By making them uncool, WRG made them—and themselves, as the brightest new agency on Madison Avenue—uber cool.

In a 2002 interview with USA today she said of her decision to handle tobacco accounts, “I wouldn’t do it now. Based on the knowledge we have today, we’d make a different decision.” She adds, “I don’t feel I owe anyone an apology.” Harding Lawrence, a heavy smoker, had died of emphysema and lung cancer a few months before.

NOT EVERYONE FOUND the agency and the act so captivating. There were of course the envious, the reactionary, and the mysoginistic. But there were also more serious critics who simply disliked Wells’ perspective of the job of an advertising agency.

Says Amil Gargano, “The mention of her name would send Carl Ally into an unbridled rage. He thought she was a complete charlatan. He resented the fact that her best work was for a cigarette. Hated what she did for Braniff, the epitome of everything he loathed about her approach. Described her agency as ‘The School of Fashion and Theatrics.’”

Well, yes, it was. She’d come to New York as an actress and theater was never far from her ideas. But she understood that there was no rule stating that the public shall respond only to the purity of a double page spread or the simplicity of a well-argued TV spot. They respond to theatrics too, and Wells’ idea was to create spectacles and let them be the advertisement.

No one in her professional life knew her better than Charlie Moss. They first met at DDB, and he then worked with her from the Jack Tinker days until the absorption of WRG into another Harper-style consortium in 1998. His first impression of Mary, as it is for so many, had been of her style.

“DDB was linoleum floors, offices painted a drab white, steel desks in every office, and two directors chairs with the canvas backs, and a chair for the person who had the office. A typewriter if you were a writer, an art board if you were an art director, and one big, BIG cork board on your wall.… Now when I first met Mary, I was shocked because her inner sanctum was very different from the rest of the agency. It was the only office that was decorated. It had an orange floor, and a French provincial credenza [desk], it was actually civilized-looking. It was the only office like that in the entire agency as far as I knew apart from maybe Bernbach’s upstairs.”

Later, when interviewing for an art director at Tinker, she and Dick Rich had been impressed by a trade campaign for Rheingold beer in the book of DDB art director Phil Parker, who had been working with Moss. Moss takes up the story:

“The idea entailed telling people that Rheingold sponsored the Mets. The Mets were, at that time, a joke, they hadn’t won a game in months, they were pathetic. And we came up with this idea that if the Mets won the pennant, we would buy everybody in NYC a beer. Then we changed it to buying everyone a beer if they won six games straight because the pennant would be out of the question. A beer party at Shea Stadium, everybody was invited, and Rheingold would sponsor it. But the Mets would not allow it to run. They felt it was making fun of them. It was withdrawn. The client loved it, everybody loved it. Anyways, it was what got me my job at Tinker. What it had in it inherently was a promotional aspect and that’s what Mary was about. Take the French Tourist Bureau at DDB. She created [a new] French tourist industry by insisting that they turn chateaus into hotels, and really market what they had so that Americans would appreciate it. Her advertising was secondary to the product that she helped to create.”

Most agencies when given the Braniff brief would have tried to find a persuasive argument to convince the traveler that the current Braniff was a better airline. Wells took it further; she took the airline apart, recreated it with fireworks, noise, and fun, and advertised that.

Advertising, and thus the advertising agency, is no longer about merely ads. Agencies have to be prepared to be about ideas that are above and beyond simple advertising. And as Mary Moore said of Mary Wells, with whom she worked in the seventies, “Her ideas were simply vast.”

In that respect, she was an indicator of things to come. As with the revolutionaries at the start of the decade who had done so much to kickstart the upheaval and move on from the past, it was Mary Wells who was now bringing in the fresh thinking.

She was the embodiment of the advertising creative person to come. The pointer to the future.