BILL BERNBACH

Have a read of the letter across the page.

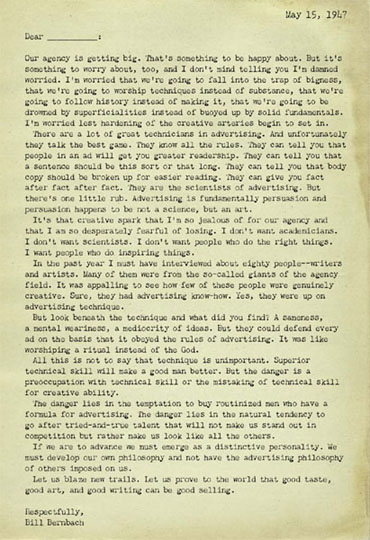

Although written by a man who turned out to be an absolute master of persuasive communication, it failed to persuade. Ironically its subject matter was an analysis of how its recipients, the management of an advertising agency where persuasion should be all, were going wrong, and what they should do to put it right. It was written in 1947 by Bill Bernbach, the creative director, to his colleagues on the board of Grey Advertising, a midsized New York agency. It was, as far as we can gather, totally ignored.

It’s a moot point as to whether Bernbach would have ever been able to wring all he wanted out of an uninspired and uninspiring Grey so we’ll never know what would have happened if they’d bought into his ideas. But certainly no steps were taken to accommodate his beliefs or adhere to his suggested policies. Spurned, Bernbach took matters into his own hands, put into practice what his letter preached and wrought as fundamental a revolution on processes and product as ever occurred in any business activity; and this all spread from one initially tiny organization in one small corner of a very large and still growing business.

It’s worth reading in full. Its dazzling lucidity and heartfelt concerns are not usually the stuff of an interdepartmental memo. And reasonable and emollient though its phrases seem, it’s a catalogue of dynamite heresies, the relentless destruction of all the practices and beliefs held as inalienable wisdom by its addressees at the time. He was a curious man in a curious business. On the receiving end of advertising, as we all are minute by minute, it’s difficult to see how anyone can get really worked up about it. It’s just there, like weather and noise and things made of plastic.

It’s only ads. In their creation, no one dies, no one even gets hurt, apart from the occasional bruised ego and crushed vanity. At best it’s fluffy entertainment, at worst an insulting, mindless assault, a disposable means to a bigger end. Ideologically, depending on your own political stance, it’s the rattling of a stick in a bucket of swill—George Orwell—or a useful tool, but merely a tool, of capitalism. An adjunct. It does not, would not, exist in its own right.

Even within advertising its practitioners often have a morosely realistic view of their role in society. Julian Koenig, one of the key figures in this story, recently expressed his regret that he’d spent his life in its pursuit, happy that he’d done it extremely well but less so that he’d done it at all; a French advertising executive published his autobiography utilizing an old and well-worn advertising gag: “Don’t tell my mother I work in advertising, she thinks I’m the piano player in a brothel.”

It’s not a business inside which you’d expect a passionate battle of competing philosophies and ideas to create volcanic heat and upheaval, still resonating sixty years later. And yet you can see the emotion it aroused in Bill Bernbach, especially when he thought it wasn’t going the way he so strongly thought it should. Strongly enough that in 1949, aged thirty-eight, an age when senior managers should be cozily slipping their feet further and further under their executive desks, Bernbach left his secure and successful job as creative director to follow his utter conviction that there was a better way to do things—and started his own agency.

Perhaps surprisingly in such a competitive business, his beliefs were not just about performance, efficacy, and success, but about the role of advertising as an intrusive force for better or for worse in the life of contemporary society. Although in interviews he would often claim that to make ads more entertaining was simply a better way to get the consumer on your side and thus more likely to be persuaded, his concerns were as much rooted in ethics as they were in efficiency. You can gauge the humanity in the man by this, one of his many quotes respected not just for their content but also their precision of thought and expression:

“All of us who professionally use the mass media are the shapers of society. We can vulgarize that society. We can brutalize it. Or we can help lift it onto a higher level.”

And note also the last sentence of the letter. He didn’t have to include “good taste” in his recipe; all advertisers have always been concerned with “what” they say but few ever worry too much about “how” they say it, as long as it achieves maximum results. But he was clearly dismayed by the crassness and soullessness of the advertising prevalent at that time simply because it was crass and soulless, and he saw that as socially corrosive, or at least debilitating.

He believed there was a better way for America’s corporations to treat their customers. Like a good theater playwright or director, he appreciated the audience was not an inert, inactive recipient but a living organism whose very reception of the message affected the message itself. He saw a lighter way, a more humorous, demotic way, that said, “Hey, we’re all in this together; you know we’re going to try and sell you something—let’s both enjoy the process.”

BERNBACH IS AN UNLIKELY HERO. Although not lacking in confidence, he could not be described as charismatic. Perhaps his most commanding asset was a pair of piercing blue eyes; certainly there was nothing else about him that demanded instant respect, short, rotund, and average-looking as he was. And yet more than sixty years later, advertising people all over the world, some entering the business two generations after he died, still talk of him with reverence. After his death in October 1982, Harper’s magazine told its readers he “probably had a greater impact on American culture than any of the distinguished writers and artists who have appeared in the pages of Harper’s during the past 133 years.”

Of how and why he got in to advertising, he said: “I don’t think that everything is measured by definite decisions—one day when I was suddenly going into advertising.… It just gradually happened. I was interested in writing. I was interested in art, and when the opportunity came along to do writing and art in advertising, I just took the opportunity.”

He had an absolute aversion to the notion that advertising could be done by formula. He was very careful to make a strong distinction between philosophy, in which he trusted, and formulae, which he recognized encouraged repetitive situations.

He believed in the arcana of creativity—not just how people worked but even how to select them. In 1964, as reported by Denis Higgins in The Art of Writing Advertising, he was confronted by an interviewer trying to analyze just how and why he was such an original advertising thinker. Asked if there were any striking characteristics unique to talented writers and art directors, he said, “One of the problems here [in this interview] is that we’re looking for a formula. What makes a good writer? It’s a danger… I remember those old Times interviews where the interviewer would talk to the novelist or the short story writer and say, ‘What time do you get up in the morning? What do you have for breakfast? What time do you start work? When do you stop work…?’ And the whole implication is that if you eat cornflakes at 6:30 and then take a walk and then take a nap and then start working and then stop at noon, you too can be a great writer. You can’t be that mathematical and that precise. This business of trying to measure everything in precise terms is one of the problems with advertising today. This leads to a worship of research. We’re all concerned about the facts we get and not about how provocative we can make those facts to the consumer.”

To Madison Avenue of that era, fixated and engorged on facts and numbers, viewing and audience ratings, this was a heresy close to madness. But it was also music to the ears of generations of creative people who felt that all their lives their ideas, thoughts and talent, the very things they believed they were hired for, were prescribed and proscribed. And it’s that sort of thinking that changed so much of advertising as then known.